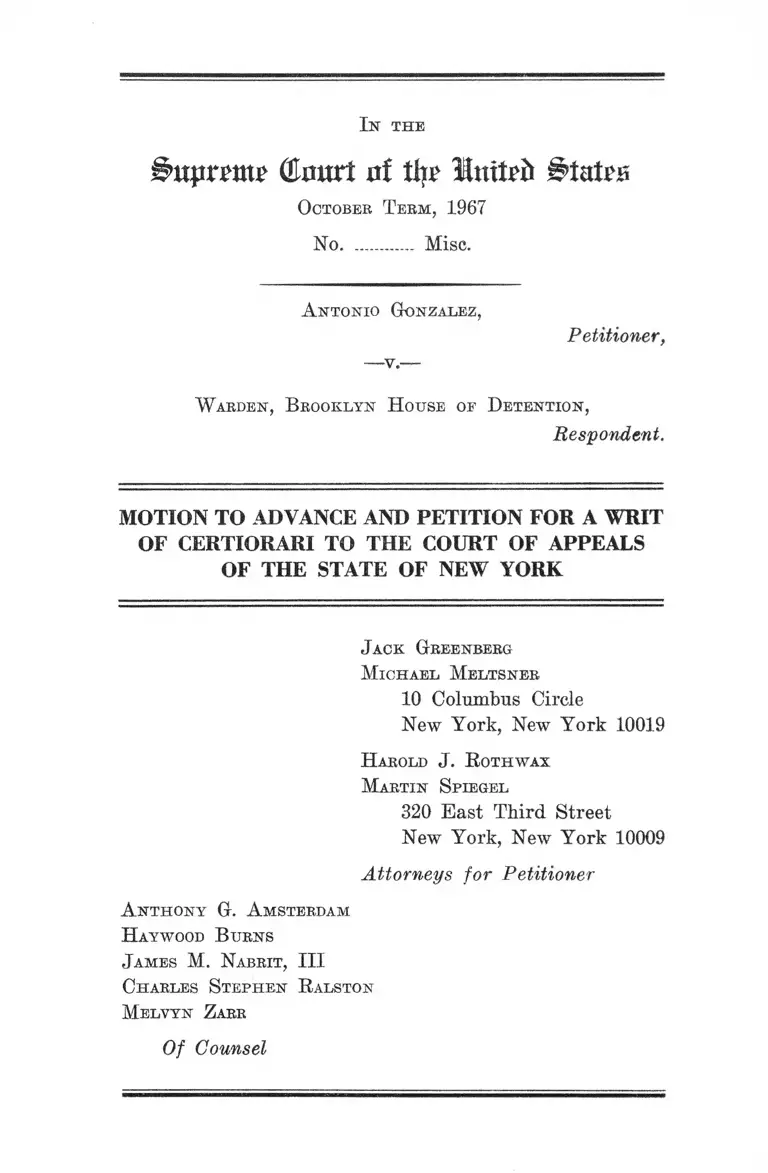

Gonzalez v. Warden Motion to Advance and Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the New York State Court of Appeals

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gonzalez v. Warden Motion to Advance and Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the New York State Court of Appeals, 1967. c90a89a1-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e47f458-4409-4bd1-bdd9-0ed543567c85/gonzalez-v-warden-motion-to-advance-and-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-new-york-state-court-of-appeals. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

In the

irtpremp (Emtrl at % littt?b #tatPH

O ctober T e r m , 1967

No............. Misc.

A n to n io Go n za lez ,

Petitioner,

W arden , B rooklyn H ouse oe D e t e n t io n ,

Respondent.

MOTION TO ADVANCE AND PETITION FOR A WRIT

OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

J ack Greenberg

M ic h a e l M eltsn er

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H arold J . R othw ax

M a rtin S pie g e l

320 East Third Street

New York, New York 10009

Attorneys for Petitioner

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

H aywood B u rn s

J am es M. N abrit , III

C h a rles S t e p h e n R alston

M elvyn Z arr

Of Counsel

I N D E X

MOTION TO ADVANCE ......................................... 1

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Citation to Opinion Below ................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................ 1

Questions Presented ................................................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 2

Statement ................................................................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below ............................................................ 5

R easons fo e G ea n tin g t h e W e it :—

Introduction ............................................................... 9

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide the

Important Question Whether the Fourteenth

Amendment Makes Applicable to the States the

Eighth Amendment’s Proscription Against Ex

cessive B ail........................................................ 13

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine

Whether the Approval by the Court Below of

Petitioner’s Pre-trial Incarceration in Default of

Bail Offends the Eighth Amendment’s Proscrip

tion Against Excessive Bail .............................. 16

III. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine

Whether Petitioner’s Incarceration Prior to

Trial Solely on Account of His Poverty Denies

Him Equal Protection of the Laws .................. 26

PAGE

IV. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine if

Petitioner Is Being Deprived of Due Process of

Law .......................................... 30

C o n c l u s io n ....................................................... 36

A ppe n d ix A

Order of Affirmance .......................................... la

Opinion of New York Court of Appeals ......... 4a

Order of the Appellate Division.......................... 12a

Stipulation ......................................... 14a

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus...................... 16a

Affidavit ................................................................ 22a

Affidavit ................................................................ 23a

A ppe n d ix B :—

Probation Report .................................................. 24a

ii

PAGE

Ill

T able of Cases

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964) ........................ 13

Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1967) ................... 27

Bandy v. United States, 82 S.Ct. 11 (1961) .............. 28

Bandy v. United States, 81 S.Ct. 197 (1961) .............. 28

Bitter v. United States, 19 L.ed.2d 15 (1967) ............. 30,33

Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 ........................................ 26

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1962) .......... 18, 26, 28

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963) ............... 26

Duncan v. Louisiana, No. 410, O.T. 1967 .................... 13

Eskridge v. Washington State Board, 357 U.S. 214

(1958) ........................................................................ 26

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961) ................. 15

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) ................ 13

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) .................. 18,26,28

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966) ..................................................... 29

Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 230 (1963) ........................ 13

Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967) ...... 13,15

Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1963) ............................ 26

Long v. District Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192 (1966) .... 27

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964) .............. ............. 13

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) ........................ . 13

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803) ................. 17

PAGE

Pannell v. United States, 320 F.2d 698 (D.C. Cir. 1963) 21

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965) ................ ......13,15

IV

Eincald v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) ...................... 26

Boberts v. Lavallee, 194 L.ed.2d 41 (1967) ................. 27

Eobinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ...... 13,14,17

Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961) ........................ 26

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951) ................. 1, 2,12,18,19,

27,30, 32,33

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967) ................. 13

White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966) .... 29

S tatutes I nvolved

An Ordinance for the government of the Territory

PAGE

of the United States, Northwest of the Eiver Ohio,

July 13, 1787, Article ii ............................................ 18

Bail Eeform Act of 1966, 18 U.S.C. §3146 ................. 24

Bill of Eights (1688), 1 W. & M. sess. 2, ch. 2 .............. 15

Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 ........................................ 15

New York Code of Criminal Procedure Sec. 553 ....2, 23,27

New York Insurance Law, Sec. 331(4) .....................19,21

O t h e e A u t h o r it ie s

Allen, Poverty and the Administration of Federal

Criminal Justice, Report of the Attorney Gener

al’s Committee on Poverty and the Administration

of Federal Criminal Justice (1963) ........................ 9, 33

Ares, Bail and the Indigent Accused, 8 C r im e and

D e l in . 12 (1962) ......................................................................... 10

Ares, Eankin and Sturz, The Manhattan Bail Project:

An Interim Report on the TJse of Pre-Trial Parole,

38 N.Y.U. L. E ev . 67 (1963) ..................................... 10

V

Bail or Jail, Criminal Court Committee of the Ass’n

of the Bar of the City of New York, 19 T h e R ecord

11 (Jan. 1964) .......................................................... 10

Botein, The Manhattan Bail Project: Its Impact on

Criminology and the Criminal Law Processes, 43

T ex . L. R ev . 319 (1965) .......................................... 9

Conference Proceedings, National Conference on Law

and Poverty (1965) ................................................... 9

Foote, The Coming Constitutional Crisis in Bail, 113

U. P a . L. R ev . 959 (1965) ........................ 9,11,15,16,18,

21, 31,33, 35

Foote, Compelling Appearance in Court: Administra

tion of Bail in Philadelphia, 102 U . P a . L. R ev. 1031

(1954) .......................................................................11,35

Foote, A Study of the Administration of Bail in New

York City, 106 U . P a. L. R ev . 693 (1958) ................. 11

Freed & Wald, Bail in the United States: 1964, A Re

port to the National Conference on Bail and Crim

inal Justice ................................................... 10,22,31,35

Freed & Wald, The Bail System of the District of

Columbia, JR Bar Sec., D.C. Bar Ass’n 1963 .......... 10

Goldfarb, No Room in the Jail, T h e N e w R e p u b l ic ,

March 5, 1966 ............................................................ 10

Goldfarb, Ransom —, A Critique of the American Bail

System (1956) ............................................................ 10

Hearings on S. 1357, S. 646, S. 647 and S. 648 before

the Sub-Committee on Improvements in Judicial

Machinery of the Committee on the Judiciary, 89th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) .............................................. 11

PAGE

Mann, 1965 U. III. L. F orum 27...................................

McCarthy and Wahl, The District of Columbia Bail

Project: An Illustration of Experimentation and a

Brief for Change, 53 Geo. L. J. 675 (1965) ..............

McCree, Bail and the Indigent Defendant, 1965 U.

III. L. Forum 1 ........................................................

National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice,

Proceedings and Interim Report (1965) ............9,11,

Note, Bail: An Ancient Practice Reexamined, 70 Yale

L. J. 966 (1961) ......................................................10,

Note, Preventive Detention before Trial, 79 Harv. L.

R ev . 1475 (1966) ........................................................

2 Pollock & Maitland, The History of English Law

582 (2d ed. 1952) .......................................................

Proceedings of the Conference on Bail and Indigency,

1965 U. III. L. F orum ..............................................

Rankins, The Effect of Pre-Trial Detention, 39 N.Y.U,

L. R ev . 641 (1964) ................................................ 11,

Report of the May, 1960 County Grand Jury of the

Circuit Court of Jackson County, Missouri ............

Report of the 3rd February 1954 Grand Jury of New

York County, New York to Honorable John A.

Mullen ......................................................................

Sills, A Bail Study for New Jersey, 87 N.J. L. J. 13

(1964) ........................................................................

1 Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England

233 (1883) .................................................................

10

10

9

23

15

11

15

9

35

10

10

10

15

In the

Oliwrt rtf tin* Hutted Staten

O ctober T e r m , 1967

No............ Mi sc.

A n to n io G onzalez ,

Petitioner,

— v .—

W arden , B rooklyn H ouse oe D e t e n t io n ,

Respondent.

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioner moves the Court to expedite consideration of

the questions presented in the attached petition for writ

of certiorari by advancing fifteen days the date by which

respondent may file a brief in opposition. In the event the

petition for writ of certiorari is granted, and this case

set down for argument, petitioner moves the Court to

advance the dates by which briefs on the merits are to be

filed and the date of oral argument.

As grounds for such motion, petitioner, by his under

signed counsel, states:

1. This case involves a substantial challenge under the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States to the pretrial incarceration of peti

tioner solely on account of his poverty. If petitioner’s

contentions should prevail, he will nevertheless have been

punished irreparably for each day he has remained in jail.

This Court has said: “Relief in this type of case must be

speedy if it is to be effective.” Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S.

1, 4 (1951).

2

2. Unless the schedule for briefing and argument is

advanced, this case may come to trial before final action

by the Court and the issues presented here could become

moot. Relief similar to that sought by this motion was

granted by this Court in Stack v. Boyle, supra. The Court

of Appeals of the State of New York expedited the appeal

in this case and heard oral argument five days after

judgment in a lower court.

3. No prejudice will be suffered by respondent by rea

son of advancing the dates of briefing and oral argument.

Counsel for respondent has informed counsel for petitioner

that respondent has no objection to advancing the date by

which a brief in opposition to certiorari must be filed to

fifteen days from receipt of the petition by counsel, and

no objection to the Court advancing the oral argument to

a date convenient to the Court. The issues raised by the

petition for a writ of certiorari were fully briefed in the

New York Court of Appeals and respondent is represented

by counsel experienced in the presentation of constitutional

issues to this Court.

4. The record in this case is short and those portions

pertinent to resolution of the questions presented have al

ready been printed in the appendix to the petition for writ

of certiorari.

W h eb eeo r e , petitioner prays that the date by which

respondent may file a brief in opposition to the petition

for writ of certiorari be advanced fifteen days and, in the

event the writ is granted, that the dates by which briefs

on the merits are to be filed and the date of oral argument

be advanced.

Respectfully submitted,

M ic h a e l M eltsn eb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorney for Petitioner

In the

£> u p rp m p C n u r t n f % I t r i t r f t S t a t e s

O ctobek T e e m , 1967

No............ Misc.

A n to n io G onzalez ,

-v.-

Petitioner,

W arden , B rooklyn H ouse of D e t e n t io n ,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Court of Appeals of the State of New

York entered on December 7, 1967.

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is as yet unreported

and is set forth in the appendix, infra pp. 4a-lla.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was issued on

December 7, 1967, infra p. la. Jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner hav

ing asserted below and asserting here deprivation of

rights secured by the Constitution of the United States.

2

Questions Presented

1. Whether the Eighth Amendment’s proscription

against excessive bail applies to the States by force of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether the approval by the court below of peti

tioner’s incarceration in default of the collateral required

by a bondsman for a secured bond is consistent with the

Eighth Amendment, on a record which demonstrates the

likelihood of petitioner’s appearance at trial and the avail

ability of conditions of release that would secure appear

ance without the necessity of incarceration prior to trial

solely by reason of his poverty.

3. Whether petitioner’s incarceration prior to trial solely

on account of his poverty denies him equal protection of

the laws.

4. Whether petitioner’s incarceration prior to trial de

prives him of due process of law because, solely on the

basis of the unregulated and arbitrary judgment of pro

fessional bondsmen, he is being unnecessarily imprisoned

before trial, and prejudiced in the preparation of his

defense.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves New York Code of Criminal

Procedure, Section 553:

In what cases defendant may be admitted to bail

before conviction. If the charge be for any crime

3

other than as specified in section five hundred and

fifty-two he may be admitted to bail, before convic

tion, as follows:

1. As a matter of right, in eases of misdemeanor;

2. As a matter of discretion, in all other cases;

the court may revoke bail at any time where such bail

is discretionary with the court.

Statement

This is a proceeding by which petitioner challenges the

constitutionality of his detention in default of $1000 hail

on charges of assaulting an officer, rescuing a prisoner,

and a weapons offense. The officer was in plain clothes

and pointing a gun at another citizen at the time of the

alleged assault and other offenses. On August 23, 1967,

Antonio Gonzalez was arrested by Detective Bernard Geik

of the New York City Police Department. On or about

November 9, 1967 he was indicted for violations of §§242,

1897, 1692 of the New York Penal Law and his case is

pending in the Supreme Court, New York County (Ind.

#4031-67).

The Court of Appeals found the facts as contained in a

stipulation between the parties:

“Detective Mitsch, the injured officer, was working

as an undercover narcotics agent with the New York

City Police Department. When he was assaulted, he

was attempting to arrest a narcotics seller who had

attacked him with a knife. Having disarmed the as

sailant, the detective was holding him at gunpoint.

Suddenly, Detective Mitsch was attacked by six as

sailants—one of whom allegedly was the relator—

who knocked the gun from his hand and beat him

4

about the head and body with cinder blocks and sticks.

This resulted in his being hospitalized and incapaci

tated for several months.

“When the relator was arraigned on August 23,

1967, in the Criminal Court of the City of New York,

his bail was set at $25,000. Several motions for a

reduction of bail were made and granted. Bail was

ultimately set at $1,000. Unable to raise $1,000 bail

or to secure a bond for that amount, the relator sought

a writ of habeas corpus in the Supreme Court, Kings

County, on October 20, 1967. Justice Vincent Damiani

dismissed that writ, saying that under the circum

stances the bail was reasonable.

“On October 23, 1967 the relator sought another

writ of habeas corpus in the Appellate Division, Sec

ond Department. On October 25, 1967 a hearing was

held before the Appellate Division. His counsel in

formed the court that the relator was 19 years of age

and had no previous criminal record, that he had

come to New York from Puerto Rico three years ago,

that he had lived with his father, brother and sister

at 734 East 5th Street, Manhattan, for the past two

years, that he was employed as a clerk by Mobiliza

tion for Youth [an anti-poverty organization] at a

salary of $45.00 per week and was attending classes

there in remedial reading and job training, and that

present in court was a social worker, employed by

Mobilization for Youth, who had known relator for

two years and who agreed to supervise relator if he

were released. Counsel informed the court that rela

tor had $100 which had been collected from friends

and relatives to be used for bail, and that he was in

jail solely because he lacked the funds necessary to

secure a $1,000 bail bond. The Assistant District At

torney, appearing for respondent, conceded that the

5

facts as stated by relator’s counsel were correct to

bis knowledge. He argued, however, that the serious

ness of the charge, the possibility of substantial pun

ishment if relator were convicted and the fact that

relator had only recently moved to New York from

Puerto Rico were factors which demonstrated that

the relator might flee if he were released without an

adequate bond. He further argued that the issue was

not whether the justices of the Appellate Division

would set the same bail as had the lower courts, but

whether the judges of the lower courts had abused

their discretion in setting the bail at $1,000. After

due deliberation of this case, the Appellate Division

determined that under the circumstances of this case,

the lower courts had not abused their discretion in

setting bail at $1,000 and dismissed the writ.” (14a-15a)

After allowing an expedited appeal in order to consider

federal and state constitutional questions raised in the

lower courts, the Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment

of the Appellate Division on December 7, 1967.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and

Decided Below

On August 23, 1967 petitioner was arrested and bail was

set at $25,000 by the Criminal Court of New York County.

September 28, 1967 petitioner’s counsel entered an appear

ance and obtained reduction of the bail to $2,500. October

10, 1967, a Justice of the Supreme Court of New York

County reduced the bail to $1,500 but refused to reduce it

further and on October 16, 1967 a Judge of the Criminal

Court further reduced bail to $1,000. Unable to raise $1,000

bail, or the collateral needed to secure a bond for that

amount, petitioner sought a writ of habeas corpus in the

6

Supreme Court of Kings County on October 20, 1967

asserting that the $1,000 bail set was excessive and denied

petitioner due process of law and equal protection of the

laws in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States. The writ

was dismissed and petitioner’s constitutional arguments

rejected.

On October 23, 1967, petitioner sought a writ of habeas

corpus before the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court,

Second Department, again asserting that he was illegally

detained in violation of the Federal Constitution:

It is submitted that excessive bail has been set in

violation of Article I, Section 5 in the New York State

Constitution and of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the United States Constitution. Furthermore,

to hold Mr. Gonzalez in jail solely because of his

poverty constitutes a denial of equal protection of

the laws in violation of Article I, Section 11 of the

New York State Constitution and the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution. To

hold Mr. Gonzalez in jail strictly because he is under

accusation and without reasonable proof showing that

he would otherwise be unavailable for trial, and with

out reasonable proof showing that he would otherwise

be unavailable for trial, and without even a hearing

to determine whether he would be available, consti

tutes a deprivation of his liberty without due process

of law, in violation of Article I, Section 6 of the New

York State Constitution and violation of Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution. (20a)

On October 25, 1967, the Appellate Division held a hear

ing at which petitioner’s counsel and respondent’s counsel

informed the court of the facts relevant to determination

7

of the character and amount of bail and argued the federal

constitutional issues raised by the petition. On the same

day, the court unanimously dismissed the writ and re

manded petitioner to the custody of respondent (12a-13a).

By special permission of the Chief Judge, an expedited

appeal was allowed and oral argument was presented to

the New York Court of Appeals October 30, 1967.

On December 7, 1967, the Court of Appeals affirmed the

dismissal of the writ by the court below. The court sum

marized the constitutional challenges to his pretrial in

carceration raised by petitioner as follows (6a) :

(1) Given facts which demonstrate a likelihood of

appearance and the existence of nonfinancial conditions

of release which would increase the likelihood of ap

pearance, the lower courts required constitutionally

excessive bail.

(2) The detention of the relator solely on account

of his poverty deprives him of equal protection of the

laws.

(3) Pretrial detention denied relator due process of

law in that (a) he is punished without trial and in

violation of the presumption of innocence without

showing of overriding necessity and (b) he is preju

diced at trial and deprived of fundamental fairness

in the guilt finding and sentencing process.

The court rejected petitioner’s contention that his bail

was “excessive” under the Eighth Amendment (10a):

. . . we cannot say that, in the circumstances of

this case, the lower courts abused their discretion in

setting bail at $1,000 and in denying relator’s request

that he be released on his own recognizance or on

8

$100 bail. The relator is accused of a vicious crime

and is subject to a possible sentence of 13 years in

prison. He bas been in New York for only three

years. While the relator contributes to the support

of his father, brother and sister, there is no evidence

that they are dependent upon relator for their support.

In sum, although he has certain roots in the com

munity, it was well within the court’s discretion to

determine that those roots were not strong enough to

assure relator’s appearance for trial if he were re

leased on his own recognizance or on $100 bail.

Because it determined petitioner’s Eighth Amendment

claim adversely to him and held $1,000 bail not excessive

the court declined to “pass upon” his contention that his

detention violated the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court appar

ently was of the opinion that if bail is not excessive under

the Eighth Amendment no due process or equal protec

tion claims could be maintained:

The relator also contends that the setting of money

bail in excess of what he can afford when a reasonable

alternative exists for insuring his presence denies

him due process and equal protection of the law. We

need not pass upon this contention since we have

concluded that the lower courts did not abuse their

discretion in determining that $1,000 hail was neces

sary for assuring the relator’s presence.

Accordingly, the order appealed from should be af

firmed (11a).

9

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Introduction

In recent years, the American money bail system has been

the subject of increasing criticism and concern among the

informed public.1 More than any other aspect of the crimi

nal process, our system of conditioning release prior to

trial on execution of a secured bond,—a system adminis

tered largely by professional bondsmen—has aroused out

rage and criticism. The nation’s chief prosecutor has char

acterized the money bail system, which of all civilized

nations only the Philippines shares,2 as “cruel and illogi

cal.”3 Judges,4 * scholars,6 administrators6 and private

1 At least two national conferences have been organized to consider all

aspects of the bail system, a reflection of that widespread concern. See,

Proceedings of the Conference on Bail and Indigency, 1965 U. 111. L.

Forum, # 1 ; National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice, Proceed

ings and Interim Beport (1965) [hereinafter cited as National Bail Con

ference]; cf. Conference Proceedings, National Conference on Law and

Poverty (1965).

2 National Bail Conference, p. 320.

3 Address by the Honorable Robert F. Kennedy, Attorney General,

National Bail Conference 297 (1965).

4 Botein, The Manhattan Bail Project: Its Impact on Criminology and

the Criminal Law Processes, 43 Tex. L. Rev. 319 (1965) (an approving

commentary upon the first movement which succeeded in translating criti

cism into reform ); see also Justice Botein’s address to the National Con

ference on Bail and Criminal Justice, National Bail Conference 18;

McCree, Bail and the Indigent Defendant, 1965 U. 111. L. Forum 1 (the

inadequacies of money bail led the writer and other United States District

Judges sitting in the Eastern District of Michigan to establish a success

ful release-on-recognizance program).

6 Foote, The Coming Constitutional Crisis in Bail, 113 U. Pa. L. Rev.

959, 1125 (1965) (a reexamination of the meaning of the Eighth Amend

ment’s prohibition of excessive bail in an historical perspective, and an

inquiry into the relationship between the proper constitutional standards

and current bail abuses) [hereinafter cited as Crisis in Bail]; Allen,

Poverty and the Administration of Federal Criminal Justice, Beport of

the Attorney General’s Committee on Poverty and the Administration of

10

researchers* 6 7 have concurred in questioning both the opera

tion, the assumptions, and the constitutionality of the

money bail system, and in calling for its reform.

Recent writings, for example, agree that monetary bail

does not even perform well its function of increasing the

likelihood of appearance at trial;8 that in most cases—as

is shown dramatically in this case—the decision whether

an accused will be released prior to trial is delegated to

the unregulated discretion of a professional bondsman

whose decision to release an accused is unrelated to the

likelihood of flight, or to constitutional requirements, and

relates only to profit motive;9 that the cost of pre-trial

imprisonment in terms of time, public funds, employment,

education, and human suffering is staggering;10 and that

Federal Criminal Justice, 58-89 (1963); Ares, Sail and the Indigent Ac

cused, 8 Crime and Delin. 12 (1962).

6 Mann, 1965 U. 111. L. Forum 27-32 (bail bonds totally obsolete and

represent the “tilted scales of justice,” in the words of the Chief Proba

tion and Parole Officer of the St. Louis, Mo., Circuit Court for Criminal

Causes) ; Ares, Rankin and Sturz, The Manhattan Bail Project: An

Interim Report on the Use of Pre-Trial Parole, 38 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 67

(1963) ; Sills, A Bail Study for New Jersey, 87 N.J.L.J. 13 (1964).

7 McCarthy and Wahl, The District of Columbia Bail Project; An

Illustration of Experimentation and a Brief for Change, 53 Geo. L.J.

675 (1965); Goldfarb, Ransom—A Critique of the American Bail System

(1965); Freed & Wald; The Bail System of the District of Columbia

(Jr. Bar Sec., D. C. Bar Ass’n. 1963).

8 Freed & Wald, Bail in the United States: 1964, 49-55; Ares, Rankin

and Sturz, The Manhattan Bail Project: An Interim Report on the Use

of Pre-trial Parole, 38 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 67, 90 (1963); Note, Bail: An

Ancient Practice Reexamined, 70 Yale L.J. 966 (1961).

9 See Report of the 3rd February 1954 Grand Jury of New York

County, New York to Honorable John A. Mullen at 2-3; Bail in the

United States 22-38; Report of the May, 1960 County Grand Jury of

the Circuit Court of Jackson County, Missouri; Bail or Jail, Criminal

Court Committee of the Ass’n. of the Bar of the City of New York, 19

The Record 11 (Jan. 1964).

10 See Freed & Wald 39-48; National Bail Conference 63-65; Goldfarb,

No Room in the Jail, The New Republic, March 5, 1966, 12; Foote,

11

the bail setting process is commonly abused to punish prior

to trial, to give an accused “a taste of jail,” or “to make an

example.”11 Criticism, however, has not been limited to

the operation of the present system. Commentators have

questioned the money bail system on constitutional grounds,

including those raised in this petition.12

One might suppose that the appearance of obviously

substantial constitutional questions against the background

of an overwhelming body of evidence documenting the

abuse and unfairness of the money bail system would have

ordinarily resulted in consideration of pertinent constitu

tional standards by this Court before the present day. But

in this area lower courts act in a constitutional vacuum.

According to Professor Foote “there is not a single intel

lectually respectable judicial decision” on the question of

application of the bail system to an indigent, National Bail

Conference, p. 227. If this judgment is correct, it reflects

only that appellate courts rarely are accorded the oppor

tunity to grapple with the principles which spell the differ

ence between liberty and jail for thousands of defendants

each day, many of whom are never convicted of any crime

or sentenced to serve time in jail. The reason for the dirth

of appellate decisions relating to pre-trial release appears

to be the impracticability of resort to protracted appellate

Compelling Appearance in Court: Administration of Bail in Philadel

phia, 102 IT. Pa. L. Rev. 1031 (1954) [hereinafter cited as Philadelphia

Bail Study]; Foote, A Study of the Administration of Bail in New York

City, 106 IT. Pa. L. Rev. 693 (1958) [hereinafter cited as New York Bail

Study] ; Rankin, The Effect of Pre-Trial Detention, 39 N.Y.U. L. Rev.

641 (1964).

11 Hearings on S. 1357, S. 646, S. 647 and S. 648 Before the Sub

committee on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of the Committee on

the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 3, 66, 130 (1965); Note, Preventive

Detention Before Trial, 79 Harv. L. Rev. 1475 (1966) New York Bail

Study 705; Philadelphia Bail Study 1039.

12 Crisis in Bail 1126 et seq.

12

procedures during a time before criminal trial moots the

constitutional issues presented. Whatever the reason, the

result is that the hammering out of doctrine through the

creative interplay of higher and lower courts—so integral

a part of law development in Anglo-American jurisprudence

—has been totally stifled in the bail area. As a consequence,

administration of release standards is, in a sense, lawless.

With deference, we believe this consideration above all

others should move the court to consideration of the ques

tions raised by the petition.

It has been over fifteen years since a bail case has sur

vived for this Court’s examination.13 The resources re

quired to be mustered to bring such a case here are far

beyond those of most counsel for the indigent accused.

Moreover, it is highly unusual for the lower courts to

process the bail proceedings and appeals therefrom with

the speed displayed in the present case. That expedited

proceeding has resulted in a significant opinion of the New

York Court of Appeals denying federal claims of the most

fundamental significance and widespread application. If

this Court is ever to consider those enormously important

federal issues, it should grant certiorari in this case.

13 Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951), survived only because this Court

granted an expedited hearing of the application for bail pending cer

tiorari, granted certiorari shortly thereafter and reversed. An expedited

hearing is requested by petitioner in the accompanying motion.

13

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide the Impor

tant Question W hether the Fourteenth Amendment

Makes Applicable to the States the Eighth Amendment’s

Proscription Against Excessive Bail.

The Eighth Amendment provides:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines

imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

In recent years, this Court has frequently granted re

view in cases seeking to apply the specific guarantees of

the Bill of Rights to state criminal proceedings. See Klop-

fer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967) (speedy tria l);

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965) (confrontation);

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967) (compulsory

process); Gideon v. Waiwwright, 372 IT.S. 335 (1963) (right

to counsel); Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 230 (1963) (stand

ard of legality of searches without a warrant); Aguilar v.

Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964) (standard for the issuance of

a search warrant); Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) (ex

clusion of illegally seized evidence); Malloy v. Hogan, 378

U.S. 1 (1964) (protection against self-incrimination);

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) (Eighth Amend

ment protection against cruel and unusual punishment).

Only this term the Court agreed to consider if the Sixth

Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial applies to the states,

Duncan v. Louisiana, O.T., 1967, No. 410. The excessive

bail clause of the Eighth Amendment is the most significant

guarantee of the Bill of Rights remaining to be considered.

Petitioner contends that the right against pre-trial deten

tion upon which the Eighth Amendment rests is a critical

aspect of the “liberty” protected by the due process clause

14

of the Fourteenth Amendment against deprivation by 'the

states. As this Court has not heretofore considered whether

the excessive bail clause of the Eighth Amendment is ab

sorbed in the Fourteenth and, if so, the character and extent

of its application, this petition plainly presents a question

appropriate for exercise of the certiorari jurisdiction.

Certiorari is particularly appropriate in the present case

because of the extraordinary effort and resources required

to present to this Court issues concerning the constitution

ality of the money bail system as applied to an indigent.

Such issues are ordinarily mooted by the supervention of

trial before they can be brought to this Court. While reso

lution of the questions raised by the petition go to the heart

of criminal law administration, this Court’s opportunities

to determine constitutional rules governing pre-trial deten

tion are rare. Fortuities of timing in the present litigation

present a unique occasion for the Court to determine issues

now decided without authoritative constitutional guidance

every day of every year in lower courts the length and

breadth of the nation.

A pronouncement by the Court that the Fourteenth

Amendment applies the excessive bail prohibition of the

Eighth to the states is particularly timely now in the wake

of the recent incorporation of the Eighth Amendment’s

other major guarantee forbidding cruel and unusual pun

ishments, Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962). To

incorporate that clause but ignore its companion—and thus

to restrain the states’ power to punish the guilty but not

their power to punish the presumptively innocent—would

be not merely irony but retardation of more than half a

millennium of Anglo-American growth in the traditions of

freedom. For, if one thing is clear in the history of the slow

and painful evolution of the modern concept of personal

liberty, it is the vital and continuing part played in that

15

history by the struggle to assure the right of pre-trial re

lease.14 * In deciding to apply specific guarantees of the

Bill of Rights to state criminal proceedings, the court has

emphasized the significance accorded these rights in the

heritage of English law, e.g. Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386

U.S. at 223-26; Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. at 403-05.

Even without the benefit of “incorporation” notions, how

ever, one could not suppose without historical and practi

cal heedlessness that the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohi

bition against the deprivation of liberty without due process

of law imposed no restraint upon a state’s power to im

prison an individual on criminal charges before those

charges had been proved and the accused’s defenses heard

at judicial trial. It would be worse than heedless to suppose

that due process of law could he said to suffer a system in

which the modern American citizen might languish for

long periods in jail without trial. Pervasive state constitu

tional recognition of the bail right supports the finding that

the Eighth Amendment’s bail clause is absorbed by the re

quirement of the Fourteenth that a state’s criminal pro

cedure conform to at least generally accepted minimum

standards of fairness.16 Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570

(1961).

14 Well before the Bill of Bights (1688), 1 W. & M. sess. 2, ch. 2,

reciting that “excessive Baile hath beene required of Persons committed

in Criminall Cases to elude the Benefit of the Lawes Made for the

Liberty of the Subjects,” and “That excessive Baile ought not to be

required,” the importance of the bail right had been recognized and its

preservation assured by statute. See Crisis in Bail 965 et seq.; 1 Stephen,

A History of the Criminal Law of England, 233-243 (1883); 2 Pollock &

Maitland, The History of English Law 582-587 (2d ed. 1952). Indeed,

protection of the bail right was the immediate purpose of the celebrated

Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 whose descendant is the Habeas Corpus Sus

pension Clause of the federal and virtually all state constitutions.

16 Bail: An Ancient Practice Reexamined, 70 Yale Law Journal, 966-

977, Appendix (1961).

16

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine Whether

the Approval by the Court Below of Petitioner’s Pre-trial

Incarceration in Default of Bail Offends the Eighth

Amendment’s Proscription Against Excessive Bail.

Once it is acknowledged that the states are forbidden by

the Fourteenth Amendment to demand “excessive bail”

within the terminology of the Eighth, the question remains

of the meaning to be assigned to that exceedingly ambiguous

constitutional command. Its simple phraseology conceals

a welter of difficulties of construction, none yet resolved by

a considered and authoritative decision of the Court. These

do not detract, however, from the inevitable conclusion that

the purpose of the Amendment was to grant a broad right

to pre-trial release.

It has been noted by the outstanding contemporary com

mentator on the bail institution, Professor Caleb Foote,

that there are three possible interpretations of the language

of the excessive bail clause of the Eighth Amendment, only

one of which is consistent with its historical context.16

First, it might be urged that the Eighth Amendment

means bail cannot be demanded in an excessive sum in cases

made bailable by other provisions of law but that the

clause of itself imports no right to pre-trial release. While

such a reading of the clause is logically possible it presents

the absurdity of a constitutional provision being merely

auxiliary to statutory law. This notion is contrary to the

whole concept of a Bill of Rights restricting a legislature,

for the right to bail could be denied and the Amendment

rendered meaningless for want of application. Such a con- 16

16 Crisis in Bail 969 et seq.

17

struction—under which the Eighth Amendment would be

nugatory in the absence of congressional or state legislation

establishing the scope of the right to bail—runs against the

first principles of a written constitution, for “it cannot be

presumed that any clause in the Constitution is intended to

be without effect” Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 174

(1803). Indeed, that construction would be inconsistent not

only with the remainder of the Bill of Rights but with the

remainder of the Eighth Amendment, for its prohibition

against excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment

have been incorporated in the Fourteenth Amendment and

applied to protect against legislative action. Robinson v.

California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

A second possible construction would be that bail cannot

be demanded in an excessive amount in cases in which a

court sets bail, but, in the absence of other statutory or

constitutional restrictions, the court always retains the

power to deny bail altogether. Such a construction would

also render the Eighth Amendment excessive bail clause

something unique and callously futile in our constitutional

system:

By making a clause say to the bail setting court that it

may not do indirectly what it is however permitted to

do directly—deny relief—the clause is reduced to the

stature of little more than a pious platitude. (Crisis in

Bail at 970)

A great deal of historical data supports the conclusion

that a third possible construction—that the excessive bail

clause creates a federal constitutional right to pre-trial re

lease—is far more likely than either of the two dryly logical

alternative suggested above. In 1789, while the excessive

bail clause was being considered as one of the proposed

amendments to the Constitution, the first Congress passed

18

Section 33 of the Judiciary Act extending an absolute right

to bail in all noncapital federal criminal cases. The avail

able materials contain “nothing to indicate that anyone in

Congress recognized the anomaly of advancing the basic

right governing pre-trial practice in the form of a statute

while enshrining the subsidiary protection insuring fair

implementation of that right in the Constitution itself.” 17

One is left to conclude that the right to bail was so funda

mental to the framers that they never questioned that the

Eighth Amendment had granted it. This conclusion is re

inforced by the passage in 1787 of the Northwest Ordinance

which stated:

. . . all persons shall be bailable unless for capital of

fenses where the proof shall be evident or the presump

tion great; all fines shall be moderate; and no cruel or

unusual punishments shall be inflicted. . . . (An Ordi

nance for the government of the Territory of the

United States, Northwest of the Eiver Ohio, July 13,

1787, Article ii).

No reason suggests itself why the inhabitants of the North

west Territory should have been given by their organic

charter greater rights in this regard than citizens of the

United States within its organic bounds. The history of the

language which became the Eighth Amendment and the

background against which it was drafted also supports this

conclusion, Crisis in Bail pp. 965-71.

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951) is this Court’s only

opinion on what constitutes excessive bail. It was decided

both before the landmark decisions under the equal protec

tion clause of Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) and

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), and before the

growth of the extensive criticism of the bail system de

17 Crisis in Bail at 972.

19

scribed supra pp. 9-11. Further, the significance of Stack

as a construction of the Eighth Amendment and a guide to

lower courts in its application is severely diminished by the

unusual factual circumstances of that case—particularly

the incredible bail figure set and its disproportion in rela

tion to figures usually set for offenses of equal gravity.

Nevertheless, we believe that Stack suggests certain

Eighth Amendment principles whose fuller development

and firm establishment can be advanced by their appli

cation to this case. The Stack opinion takes the view that

the sole permissible function of monetary bail is to assure

the accused’s presence at trial. “Bail set at a higher figure

than an amount reasonably calculated to fulfill this pur

pose is ‘excessive’ under the Eighth Amendment.” (Id. at

5). “Since the function of bail is limited, the fixing of bail

for any individual must be based upon standards relevant

to the purposes of assuring the presence of that defend

ant” Ibid. Stack thus suggests the invalidity of a bail de

termination if (a) the amount set or the form of security

required is more onerous than could reasonably be thought

necessary to induce the accused’s presence at trial, or (b)

in setting the amount or form of security, inadequate in

dividual consideration is given to the circumstances of

each particular defendant.

The administration of the state’s bail system in the pres

ent case fails to conform to either standard, properly in

terpreted. Petitioner is detained solely because he cannot

afford the price of freedom, which in this case is solely the

collateral required (under no obligation or explicit legal

provision of the state) by a bondsman; petitioner does

have sufficient funds to pay the $50 lawful premium, New

York Insurance Law §331(4). There is no evidence of any

legitimate individual circumstance as to support a finding

that petitioner would not appear if released on his recogni

20

zance, on $100 cash bail, or subject to non-finaneial condi

tions—but that he would appear if he were able to post a

$1,000 secured bond.

On the contrary, all the evidence points to a likelihood

of appearance. Petitioner’s character and roots in the com

munity are inconsistent with flight unless anyone charged

with a serious crime is to be considered more likely than

not to flee. The accused is 19 years old. For the past two

years he and his brother and sister have lived with their

father at the same address on New York’s lower East Side.

Petitioner’s mother is deceased. At time of the events lead

ing to his arrest he was working as a clerk for Mobiliza

tion for Youth, Inc., an anti-poverty organization with of

fices on the lower East Side, whose attorneys are among

those who represent him. With his eranings of $45 per

week he helped his father support the younger children in

the family. He also attended classes in remedial reading

and job training sponsored by Mobilization for Youth in

order to improve his prospects for future employment.

He has no criminal record.18 It has been stipulated by the

parties that a social worker, in the employ of Mobilization

for Youth, who has known petitioner for two years, agreed

to supervise him if he were released on his recognizance or

$100 cash bail.

That bail is excessive here is strongly suggested by the

fact that the pre-trial parole recommendation standards

presently in operation in the City of New York are more

than met by this petitioner. Appended to the petition is a

18 Whether the accused’s involvement in the instant prosecution amounts

to a criminal violation is, of course, an issue for the trial jury and not

for a bail setting court. One of the issues at trial, however, will be whether

Mr. Gonzalez knew that Detective Mitsch was a police officer, or reason

ably believed that he was a drug addict who was attempting to rob another

person at gun point. This is not a case where conviction is, by any means,

assured.

21

copy of form No. 40-43-167 Rev. of the New York Depart

ment of Probation, which administers release on recogni

zance standards in the courts of the City of New York Ap

pendix B, infra p. 24a. The form reveals that a score of

five points on the basis of employment, residence, and

similar considerations is sufficient to result in a recom

mendation of such release. Read in light of the stipulated

facts petitioner has over ten points, or twice that neces

sary for release on parole. Thus, the only explanation for

the denial of release in this case appears to be that peti

tioner is charged with serious crime. But money bail re

quirements may not constitutionally be substituted for

adjudication of guilt at trial, or made the sole basis for

application of a financial release test to an indigent.

One additional point must be stressed. Bail in this case

is $1,000. The premium for such a bond is $50, New

York Insurance Law §331(4). The lower courts thus ap

parently had no great concern for the likelihood of flight,

setting bail as they did in an amount that could statutorily

be made by any man with $50 in his pocket. Petitioner has

$100 in savings and contributions by friends. But under

New York law, in these circumstances, petitioner’s release

is “entirely up to the bondsman, who may be satisfied with

the . . . [statutory] fee or demand an additional under-the-

table sweetener, or require collateral less than, equal to or

greater than the amount of the bond, or simply refuse to do

business with the defendant at all” Crisis in Bail, 1160. As

one federal judge has put i t : “The effect of such a system

is that the professional bondsmen hold the keys to the jail

in their pockets” Parnell v. United States, 320 F.2d 698,

699 (D.C. Cir. 1963). The effect of the $1,000 bond de

manded of petitioner is simply to empower the private

bondsman, a business man operating pursuant to self-

interest, to decide whether petitioner shall be jailed or free.

22

On Ms decision alone, petitioner, by reason of Ms poverty,

is now imprisoned. Any interest government has in keep

ing appellant under lock and key for more than the ap

proximately four pre-trial months he has already served

lies totally in the hands of this private businessman, whose

judgment as to who should be released is unregulated by the

state and whose abuses, in New York City, are legion. See

Bail in the United States: 1964 35. One thing is clear: this

delegation of the critical decision to the bondsman does not

result in a delegation of public policy, or of the Constitution,

along with it.

The reduction of bail from $25,000 to $1,000 by the New

York courts obviously reflects a belief that there is no

serious risk of flight present here, and demonstrates beyond

peradventure that this impoverished petitioner is detained

solely because of the reflex response of the antiquated

money bail system. There can be no other explanation for

the continuous reduction of the bail, unless the courts below

sought only to immunize themselves from a charge of ex

cessiveness by lowering the absolute amount in the knowl

edge that that amount made no difference—a cynical as

sumption which we do not believe should be indulged.

Given the purpose of bail, to secure pre-trial liberty rather

than detention, the state should be required to come forward

with some specific evidence to show that it is likely a de

fendant may flee before a bail figure which results in de

tention is sustained. In the instant case, aside from the

bare accusation, the only factor which has been suggested

is that prior to three years ago petitioner lived in Puerto

Rico. Given the affirmative evidence of petitioner’s roots

in New York, including two years residence with his family

at the same address, detention on the basis of this one

added factor is untenable; it would effectively set up a pre

sumption against release of Puerto Ricans residing in

23

New York, and charged with any substantial offense, re

gardless of their roots in the state.19

Under the law of New York, if the lower court had felt

that there was evidence that the accused would not present

himself at the time of trial, it could have denied bail

altogether. N.Y. Code of Grim. Proc. §553. Evidentally

this was not the judgment of those courts below because bail

has been set. In point of fact the accused has remained

in jail not because if released he can be expected to flee

(if that were the case the bail would be far more than

$1,000) but because he is too impecunious to afford the

ransom which the state—through the agency of a profes

sional bondsman—seeks to extract.

In view of the historical background of our bail system,

its purpose, and fundamental American constitutional prin

ciples against discrimination on the basis of poverty, we

submit that bail is excessive when a financial condition

which results in detention is exacted for pre-trial release

when nonfinancial conditions would accomplish the same

likelihood of appearance at trial. In this case, it has never

been suggested that the social worker who has known peti

tioner for two years and who stated that he would supervise

petitioner if he were released prior to trial would not per

form this function. Where the evidence shows that there

are non-monetary conditions of release which will result

in appearance without detaining an accused, the courts

19 We call the court’s attention to the address of Judge Wade H.

McCree, Jr., of the United States District Court of the Eastern District

of Michigan published in the proceedings of the National Conference on

Bail and Criminal Justice, pp. 52-53. Judge McCree stated:

I might observe further that in the Eastern District of Michigan we

sit in a courthouse which is five minutes from the tunnel which

leads to Canada and 15 minutes from a bridge which connects with

the same country. We have found this not to be a complicating factor.

24

should be bound by the Eighth Amendment to choose them.20

Thus, petitioner’s circumstances present a particularly

propitious case in which this Court may examine—free of

the necessity for reviewing complex judgments of fact and

probability—whether the Eighth Amendment does or does

not prohibit the entirely purposeless incarceration of an

indigent for the sole reason of indigency.

To petitioner’s contention that the bail conditions set

here were unconstitutionally more onerous than reasonably

necessary to assure his appearance, the Court of Appeals

answered (11a):

In sum, although he has certain roots in the com

munity, it was well within the court’s discretion to

determine that those roots were not strong enough to

20 The federal Bail Reform Act of 1966, 18 U.S.C. §3146, is perhaps

the best existing model of a pre-trial release system in use. I t was pre

sented to the Court of Appeals only as exemplary of the options open to

a bail setting court. The Act provides that, in noncapital cases, a person

charged with a crime shall be released on his personal recognizance or

upon the execution of an unsecured appearance bond. I f the judicial

officer expressly determines that such a release will not reasonably assure

the appearance of the person, he may either in lieu of or in addition to

the above methods impose another condition or combination of conditions

which will assure appearance—resorting to the least stringent that will

accomplish the desired purpose. These conditions include:

(1) placing the person in the custody of a designated person or or

ganization agreeing to supervise him;

(2) placing restrictions on the travel, association, or place of abode of

the person during the period of release;

(3) requiring the execution of an appearance bond in a specified amount

and the deposit in the registry of the court, in cash or other security

as directed, of a sum not to exceed 10 per centum of the amount of

the bond, such deposit to be returned upon the performance of the

conditions of release;

(4) requiring the execution of a bail bond with sufficient solvent sureties,

or the deposit of cash in lieu thereof; or

(5) imposing any other condition reasonably necessary to assure ap

pearance as required, including a condition requiring that the per

son return to custody after specified hours.

25

assure relator’s appearance for trial if he were re

leased on Ms own recognizance or on $100.00 bail.

It is unreal, however, to talk in terms of lower court

discretion. In this case the bail decision has been delegated

to various agents of insurance companies. They could ac

cept the $50 premium which he can pay or require col

lateral which he can not pay, solely at their caprice. Such

discretion as many have been exercised here permits an

arbitrary, unregulated, and private business judgment to

determine petitioner’s freedom. In addition, the facts show

ing whether or not petitioner is a good risk are contained

in the stipulation which is part of the record. These were

also the facts before the lower courts. As is the practice in

bail determinations, no actual testimony was before those

courts. They had no opportunity to observe demeanor on

the stand. Since petitioner contends that to incarcerate

him on the stipulated facts is to require constitutionally

excessive bail, a question of constitutional law—-not of

lower court discretion—is plainly presented, see Stack,

supra at 6.

Finally, petitioner asks this Court—as he asked the Court

of Appeals—to set the proper constitutional standard: that

an indigent may not be required to post a secured bond

which he cannot make when an acceptable nonfinaneial

condition of release is available to facilitate pre-trial re

lease as well as protect the state’s interest in appearance.

As this standard has not been articulated by this Court

or by the New York Courts, it is difficult to understand

how the lower courts could have exercised any informed

discretion in committing the issue of petitioner’s pre-trial

liberty to the bondsman’s judgment.

26

III.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine Whether

Petitioner’s Incarceration Prior to Trial Solely on Ac

count of His Poverty Denies Him Equal Protection of

the Laws.

This Court’s decisions under the Equal Protection Clause

have struck down numerous state practices which differen

tiate between rich and poor in the administration of the

criminal process. Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956)

(denial of free criminal trial transcript necessary for ade

quate appellate review); Eskridge v. Washington State

Board, 357 U.S. 214 (1958) (denial, absent trial court find

ing that “justice will thereby be promoted,” of free crimi

nal trial transcript necessary for adequate appellate re

view) ; Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963) (denial,

on trial court finding that appeal is frivolous, of free crimi

nal trial transcript necessary for adequate appellate re

view) ; Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1963) (denial, absent

public defender’s willingness to prosecute appeal from de

nial of state coram nobis petition, of free transcript of

coram nobis proceeding necessary to perfect state appellate

jurisdiction); Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1962)

(denial, absent appellate finding that appointment of coun

sel on appeal would be of value to defendant or the appel

late court, of free appointment of counsel on appeal as of

right from criminal conviction); Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S.

252 (1959) (denial, in default of $20.00 filing fee, of motion

for leave to appeal a felony conviction); Smith v. Bennett,

365 U.S. 708 (1961) (denial, in default of $4.00 filing fee,

of leave to file habeas corpus petition); Rincald v. Yeager,

384 U.S. 305 (1966) (indigent sentenced to prison may not

be forced to pay for appeal transcript out of prison earn

27

ings). See also Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1967);

Roberts v. Lavallee, 19 L.ed.2d 41 (1967); Long v. District

Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192 (1966).

It cannot be denied that there is an apparent inconsist

ency between these decisions and the administration of the

money bail system which petitioner has challenged. Exam

ination of this inconsistency by the Court is overdue.21 It is

ironic that we freely provide an indigent with transcripts

and lawyers after conviction but deny him liberty before

trial solely because of poverty. Such a result converts the

bail system into a device which detains as many poor per

sons as possible rather than “a procedure the purpose of

which is to enable them to stay out of jail until a trial has

found them guilty” Stack v. Boyle, supra. It is an invidious

discrimination, and denies petitioner in the most obvious

and offensive way his constitutional right to equal protec

tion.

It bears repeating that, under the laws of the State of

New York, the lower courts could have denied petitioner

bail if there was any evidence suggesting that Mr. Gon

zalez would not be likely to appear. N. Y. Code of Criminal

Procedure §553. Once bail is set, to set a figure which

21 The New York Court of Appeals decided that it “need not pass

upon” petitioner’s equal protection and due process challenges to the

money bail system because it found that the bail set was not constitu

tionally excessive. Such a view of the due process and equal protection

clauses is misconceived. Regardless of whether bail is “excessive” under

the Eighth Amendment, the questions remain:

(A) whether, consistently with the equal protection clause, a state may

condition the right of pre-trial release upon the possession of suffi

cient funds to make whatever bond is set, thus denying indigents

release by sole reason of their poverty; and

(B) whether, consistently with the due process clause a state may adopt

a system under which the decision to detain or release a man

during the pre-trial period is relegated by a financial test to the

arbitrary and unregulated regime of professional bondsmen.

28

cannot be met only results in detaining the poor, not those

likely to flee. In Griffin, supra and Douglas, supra, the

state urged that free transcripts and appointment of at

torneys could be denied to the poor because there is no

constitutional right to appeal. The Court rejected these

contentions, holding that as long as the state granted access

to the appellate courts it could not be denied to some per

sons discriminatorily on the basis of wealth. In light of

these decisions, we fail to see how the state can justify

withholding pre-trial liberty from the poor man once it has

been determined, by setting bail in the first place, that his

release is justified.

The only Justice of this Court who has voiced his views

on the application of the Court’s equal-protection cases to

the bail system has expressed agreement with petitioner’s

position. Considering the impact of the equal protection

clause on an indigent’s request for release on his own

recognizance pending appeal from conviction, Mr. Justice

Douglas stated the question: “Can an indigent be denied

freedom, where a wealthy man would not, because he does

not happen to have enough property to pledge for his free

dom?” Bandy v. United States, 81 S. Ct. 197, 198 (Douglas

J. 1960). The Justice subsequently answered the question

in the negative, concluding that “no man should be denied

release because of indigence. Instead, under our consti

tutional system, a man is entitled to be released on ‘personal

recognizance’ where other relevant factors make it rea

sonable to believe that he will comply with the orders of

the Court.” Bandy v. United States, 82 S. Ct. 11, 13 (Doug

las, J. 1961). We venture to suggest that both the question

and the answer put by Justice Douglas at least are equally

compelling in a case, like the present one, where the right

to pre-trial liberty is at issue; and we urge that certiorari

29

be granted so that the full Court may consider and express

its views on the matter.

That the system of conditioning pre-trial release on finan

cial bail is a long-suffered discrimination traceable to the

days of medieval unconcern for the impoverished does not

insulate it from condemnation under the Fourteenth

Amendment. The argument from tradition

reflects a misconception of the function of the Constitu

tion and this Court’s obligation in interpreting it. The

Constitution of the United States must be read as em

bodying general principles meant to govern society

and the institutions of government as they evolve

through time. It is therefore this Court’s function to

apply the Constitution as a living document to the legal

cases and controversies of contemporary society.

(White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401, 408 (M.D. Ala.

1966) (three-judge court)).

Recently, the Court struck down Virginia’s time-honored

poll tax of $1.50 as a prerequisite to voting in state elec

tions on the ground that “Voter qualifications have no rela

tion to wealth nor to paying or not paying this or any other

tax” Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966). In finding wealth a “capricious” and “irrele

vant factor” the Court addressed itself to the contention

that the poll tax was “an old familiar form of taxation”

and rejected history as sufficient to support discrimination

on the basis of property:

In determining what lines are unconstitutionally dis

criminatory, we have never been confined to historic

notions of equality, any more than we have restricted

due process to a fixed catalogue of what was at a given

time deemed to be the limit of fundamental rights. See

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1, 5-6. Notions of what con

30

stitutes equal treatment for purposes of the Equal Pro

tection Clause do change (emphasis in original).

Thus, notwithstanding ancient abuses against the poor,

whether the Constitution today decrees that the financial

position of one charged with crime shall have no place in

determining the character of treatment he receives from

the state is a substantial question. This is especially true

with respect to pre-trial liberty of an accused for: “the

function of bail is limited, [and] the fixing of bail for any

individual defendant must be based upon standards rele

vant to the purpose of assuring the presence of that de

fendant.” Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1, 5 (1950) (emphasis

added). Fixing bail for petitioner in an amount which he

cannot pay because of poverty tells the poor that justice is

for sale. It is not basing release upon “standards relevant”

to the purpose of assuring presence, but denying release in

violation of the Constitution of the United States.

IV.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine if Peti

tioner Is Being Deprived of Due Process of Law.

That pre-trial detention imposes punishment is obvious.

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1, 4 (1951); and cf., Bitter v.

United States, 19 L. ed. 2d 15 (1967). A jailed accused loses

his liberty, the most precious of rights, as completely as

does any convict. In addition, petitioner has been sub

jected to severance of family relations, loss of pay, loss

of employment, loss of educational opportunity, and the

normally inhumane conditions in available pre-trial deten

tion facilities—poor food and housing, overcrowding, in

adequate recreational and other facilities, essential rudi

mentary comfort and decency. “ [A]t the time an accused

is convicted and sentenced to imprisonment, his standard

31

of living is almost certain to rise.” 22 As the National Con

ference on Bail and Criminal Justice put i t :

“His home may be disrupted, his family humiliated, his

relations with wife and children unalterably damaged.

The man who goes to jail for failure to make bond is

treated by almost every jurisdiction much like the con

victed criminal serving a sentence” (Bail in the United

States: 1964, 43.)23

It is quite possible that the only imprisonment an in

digent accused may suffer is that before trial while sup

posedly presumed innocent for after serving his pre-trial

jail term he may be acquitted or, if convicted, have his case

concluded by a disposition that does not include imprison

ment. A recent project of the Vera Institute of Justice ob

tained the release of persons who had initially been held

in custody on high bail:

Five percent of the persons released through bail

reevaluation failed to appear for trial. Of the 95%

of the released persons who did return for trial, 52%

22 Other common restrictions of the detention jail are censorship of

mail, restrictions on newspapers and periodicals, a frequently total prohi

bition on the use of the telephone, inadequate facilities for confidential

conversations with lawyers and others, including restricted visiting privi

leges only for close relatives and restriction of visits to times whieh are

particularly inconvenient to members of the working class. Foote con

cludes that “these limitations are as unnecessary to the legitimate purpose

of detention—security—as is the line up and in their contempt for man’s

dignity and their probable tendency to coerce guilty pleas far more

pernicious as a contamination of the values for which due process stands.

Whether or not such restrictions are deliberately intended to punish and

humiliate, they certainly have that effect and some judges use pre-trial

detention explicitly for punitive purposes. For example, to give the ac

cused ‘a taste of jail’.” Crisis in Bail, 1144-45.

23 I t should be noted that society pays dearly for punishing the accused.

Pre-trial detention cost the federal government $2 million in 1963. In

New York City alone costs run to $10 million per year. Bail in the

United States: 1964, 40-41.

32

were acquitted or had their charges dismissed and only

20% were ultimately sentenced to prison terms.” (Let

ter from Mr. Herbert Sturz, Director, to Mr. Michael

Meltsner, attorney for petitioner, dated November 14,

1967 and attached to Petitioner’s Reply Brief in the

New York Court of Appeals.)

To force one not convicted of crime to suffer punishment

of this magnitude for no reason other than poverty violates

fundamental principles of due process. Unless pre-trial

freedom is assured “the presumption of innocence, secured

only after centuries of struggle, would lose its meaning”

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1, 4 (1951). Our system of justice

does not permit incarceration because of generalized specu

lation of a risk of flight: ‘that is a calculated risk which

the law takes as the price of our system of justice . . .

[T]he spirit of the procedure is to enable [defendants] to

stay out of jail until a trial has found them guilty” (Id.

at 8). (separate opinion.)

The due process implications of the money bail system

are even more serious where detention is at the whim of

the bondsman. As petitioner has enough funds to pay the

premium for a bond of $1,000, see supra, p. 19, the dis

abilities he has suffered and continues to suffer depend

solely on whether a professional bondsman chooses to exer

cise his absolute discretion to require collateral or not. The

bondsman has unlimited power to refuse to write a bond

for any individual for any reason, however capricious and

unrelated to the concerns of the public. As there is no

supervision over the amount which is demanded as col

lateral, a judge fixing bail in the amount of $1000 may as

sume that the defendant is faced only with the legal pre

mium of $50, while the reality may be that he will be re

quired by the bondsman to put up property very nearly

33

approximating the entire amount of the bond. The bonds

man thus becomes the arbiter of pre-trial release, not the

judge. Without any legal or social duty to grant a bond,

his motivation at best is simply “a matter of dollars and

cents;” at worst, a compound of every arbitrary and dis