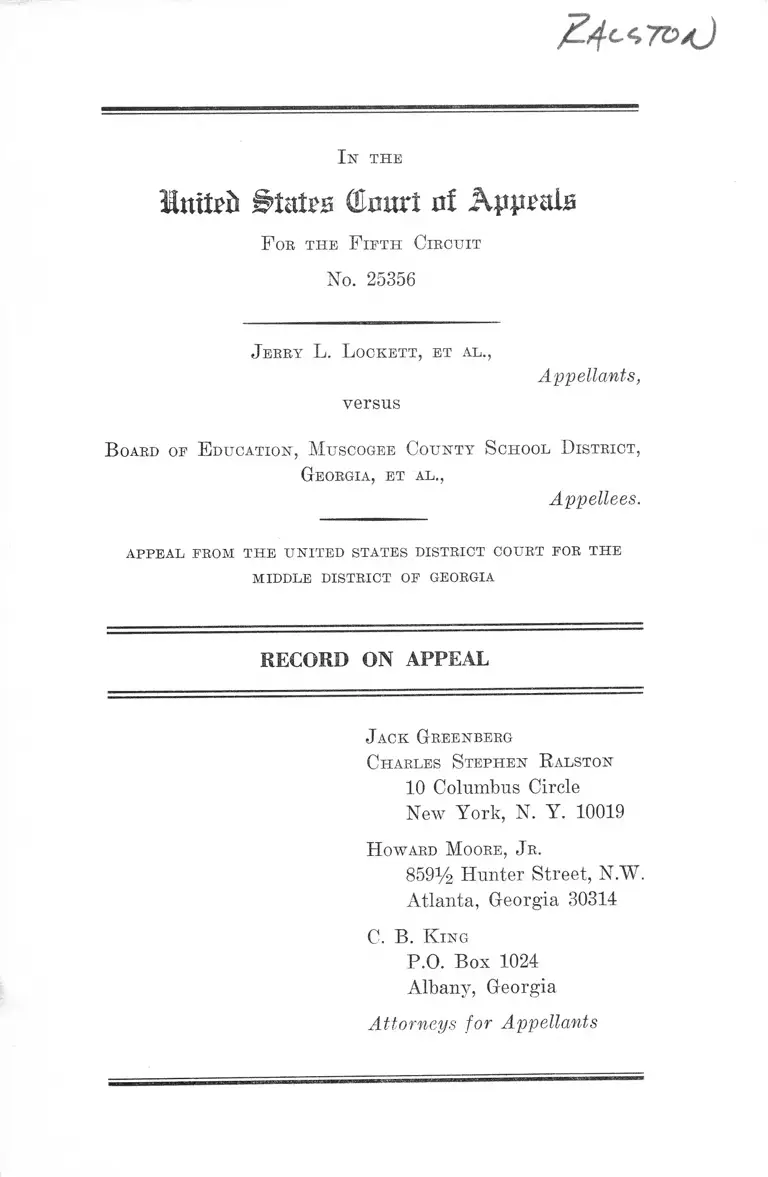

Lockett v. The Board of Education of Muscogee County School District Record on Appeal

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lockett v. The Board of Education of Muscogee County School District Record on Appeal, 1967. 3b732c79-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e653497-346d-446e-97f3-7f69e49999d2/lockett-v-the-board-of-education-of-muscogee-county-school-district-record-on-appeal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/?4c<i7Z>/J

I n t h e

Intfrii States §0nri nf Ap^ala

F ob th e F if t h C ircuit

No. 25356

J erry L. L ockett , et al .,

versus

Appellants,

B oard of E ducation , M uscogee Co u nty S chool D istrict ,

Georgia, et al ..

Appellees.

APPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

M IDDLE D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA

RECORD ON APPEAL

J ack G reenberg

Charles S tephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

H oward M oore, Jr.

8591/2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

C. B. K ing

P.O. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Plan to Desegregate, etc. (Exhibit A) .......... ............ 1

Resolution to Amend Plan, etc. .................. ................ 5

Motion for Summary Judgment ............ .................... 7

Appendix A —Explanatory Letter ............... ..... 16

Appendix B— Choice Form ............. .................... 18

Motion to Allow Appearance of Counsel ............... . 20

O rder.................................................................................. 21

Certificate of Service..................................................... - 21

Notice of Motion ...................................................... — 22

Motion for Further Relief .... - 23

Certificate of Service ..................................................... 30

Notice of Motion ................... ................................ .......... 31

Motion for Order Entering Decree, etc..................... 32

Certificate of Service ............. ................. .......... .......... 34

Response of Defendant to Plaintiffs’ Motion for an

Order Entering a Decree, etc. ............................ 35

Transcript of Proceedings ........ ....... ............ ....... -.... 39

PAGE

Certificate 121

Memorandum Opinion and Order on Plaintiffs’ Mo

tion for Further Relief ........................................... 122

Notice of Appeal .......................................................... 132

Designation of Record on Appeal ............................... 133

Certificate of Service...................................................... 135

Clerk’s Certificate .......................................................... 136

T estim on y

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw

Direct .................................................................... 10

Cross ...................................................................... 60

Redirect ............................................................ 94, H3

Recross .............................................................. 113

John R. Kinnett

Direct .................................................................... 96

Cross ...................................................................... 97

T. Hiram Stanley-

Direct .................................................................... 98

Cross ..................................................................... 100

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Robert A. Lewis

Direct ................................................................... 105

Cross ..................................................................... 108

Redirect ............................................................... H I

Recross ................................................................. 112

ii

PAGE

I l l

E x h ib it s*

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits:

1— List of Schools ........ -................... -..... -......... 68

2— Packet ...........................-........ -...................... - 69

3>—Application ........................... -..................... - 85

4— Application ........................................................ 85

5— Application ..... .................................................. 85

PAGE

* Exhibits not printed in Record.

I.

The Board of Education of the Muscogee County School

District, in continuation of its efforts to eliminate, with all

deliberate speed, discrimination because of race or color

between the pupils of the school district, hereby declares

that it will begin to desegregate the schools of the Muscogee

County School District by starting in September, 1964,

with the twelfth grade, and the Board of Education will

desegregate one lower grade each succeeding year until

desegregation shall have been accomplished throughout the

school district.

II.

The Board of Education maintains that the best interests

of the citizens of Muscogee County School District will

prevail when the Board controls the assignment of pupils

to the various school plants and facilities. The Super

intendent of Education is hereby directed to continue the

maintenance of school attendance areas for each school by

keeping a map and word description of each attendance

area. The Board of Education will continue its long estab

lished policy of assignment of pupils to attendance areas

in the Muscogee County School District in order to pre

serve the orderly process of administering public education.

III.

Pupils shall attend the school within the attendance area

in which they reside, but transfers, upon the written re

quest of a pupil and his parents or his legal guardian or

upon the discretion of the Superintendent of Education,

A Plan to Desegregate the Schools of the Muscogee

County School District, Georgia

(Exhibit “A” )

2

may be made, without regard to race or color, whenever

it is in the interest of the pupil or the efficient administra

tion of the Muscogee County School District.

IV.

The Board of Education hereby establishes February

1-15, 1964, as the period in which to receive written appli

cations from pupils and parents or legal guardians for

transfers and reassignments to the twelfth grade of a

high school other than the one to which the pupil is cur

rently assigned in the Muscogee County School District.

The written applications setting forth reasons for trans

fers and reassignments will be evaluated and either ap

proved or rejected by the Superintendent of Education no

later than April 1, 1964, and written notice mailed to

parents at the address shown on written application no

later than three days after the decision by the Super

intendent of Education. The pupil and parents or legal

guardian may appeal in writing the decision of the Super

intendent of Education no later than the regular April

meeting of the Board of Education. The final decision of

the Board of Education will be made no later than May 1,

1964, and the pupil and parents or legal guardian will be

given written notice at the address shown on written appli

cation of the decision by the Board of Education within

fifteen days.

Y.

The Board of Education will consider written applica

tions for transfers and reassignments for new pupils mov

ing into the school district after February 15, 1964, no

later than August 1, 1964. All pupils must accept the

A Plan to Desegregate the Schools of the Muscogee

County School District, Georgia

3

original assignment to the school within the attendance

area in which the pupil resides, but will be permitted to

file written application for transfer and reassignment by

the Superintendent of Education.

VI.

All newcomers moving into the Muscogee County School

District after August 1, 1964, must register and attend

the school in the attendance area in which they reside, but

may file written application with the Superintendent of

Education for transfer and reassignment to the twelfth

grade of another school. Such written applications will

be processed as expeditiously as possible by the Super

intendent of Education.

A Plan to Desegregate the Schools of the Muscogee

County School District, Georgia

VII.

All hardship cases, upon written application and full

explanation of the facts in the case, will be given full and

sympathetic consideration by the Superintendent of Edu

cation and the Board of Education.

VIII.

In the administration of this plan the Superintendent of

Education is directed to take into consideration all criteria

that may affect the best interest and welfare of the pupils

and the efficient administration of public education in the

Muscogee County School District, but no consideration

shall be given to the race or color fo any pupil.

IX.

The same procedure for filing written applications for

transfers and reassignments and approving or rejecting

4

such, written applications for transfers and reassignments

will prevail in 1965 and each year thereafter as outlined

for the school year beginning September, 1964.

A Plan to Desegregate the Schools of the Muscogee

County School District, Georgia

X.

The Board of Education, in its discretion, may revise,

change, or amend these rules and regulations or any one

of them.

Muscogee County School District

Columbus, Georgia

September 12, 1963

5

W hereas, this Board has reviewed its Plan to desegre

gate the schools of this District with all deliberate speed

and has surveyed its personnel and physical facilities and

desires to further amend its Plan so as to fully comply

with the law in such cases made and provided:

Now, therefore, be it resolved, that a parent or legal

guardian of any child now a resident of Muscogee County

who will enter any grade, including Kindergarten, in the

Muscogee County schools in September, 1967, may, during

the period from March 1 through March 31, 1967, make

written application at the school now attended by said

child or at a school in the area in which the residence of

said child is located, to enroll said child at the school of

such pupil’s choice, and such pupil shall have the right to

attend such school provided that the capacity of such

school is sufficient to enroll all pupils desiring to attend

such school. In any case where the capacity of any school is

not sufficient to enroll all pupils applying for attendance

at such school, those pupils residing nearest the school will

be enrolled and the remainder of such pupils will be as

signed by the Superintendent and his staff to other schools

which have available space and are near the residence of

said pupils.

B e it fu rth er resolved, that any pupil now a resident

in said County who does not apply as above provided at

any particular school for the next school year shall register

and enroll at the school the pupil is now attending or at

a school in the area in which said pupil’s residence is located.

B e it fu rth er resolved, that any new pupil entering the

school system for the first time must make written appli-

Resolution to Amend the Plan to Desegregate the

Schools of Muscogee County, Georgia

6

Resolution to Amend the Plan to Desegregate the

Schools of Muscogee County, Georgia

cation to the Superintendent to attend the school of such

pupil’s choice and, if space is available, such pupil will

be enrolled at such school, and if space is not available,

such pupil will be assigned by the Superintendent to a

school having available space which is near to the residence

of such pupil.

B e it furth er resolved, that the Superintendent shall

cause to be delivered a copy of this resolution to each pupil;

now attending Muscogee County schools on or before Feb

ruary 20, 1967, and the Superintendent shall supply the

principal of each school with sufficient written forms to

enable any pupil who desires to do so to make application

to attend the school of such pupil’s choice. The Super

intendent shall also give copies of this resolution to the

news media in this County and to any resident requesting

copy of same. The Superintendent shall also cause a copy

of this resolution to be printed in a newspaper in this

County once a week for four weeks immediately preceding

March 1, 1967.

B e it fu rth er resolved, that this Board review its Plan

each year and make such amendments to said Plan as it

may deem desirable.

# * *

This resolution was unanimously adopted by the Muscogee

County Board of Education, Muscogee County School Dis

trict, Columbus, Georgia, at its regular meeting held on

January 31, 1967.

7

(Filed February 1, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

Plaintiffs, by their undersigned attorneys, hereby move

this Court for summary judgment under F.R.C.P. 56, grant

ing an immediate order for additional relief in the present

case and in support of such motion would show the fol

lowing :

1. On December 29, 1966, the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit rendered a decision in thd

case of United States of America and Linda Stout v. Jeffer-

son County Board of Education, et al., No. 23345, and six

companion school cases. In that decision, the Fifth Circuit,

settled a number of important issues regarding the re

quirements of plans for school desegregation in this Circuit.

In the opinion the Court made it clear that the proposed

decree which was attached as an appendix:

[is] intended, as far as possible, to apply uniformly

throughout this circuit in cases involving plans based

on the free choice of schools. School boards, private

plaintiffs, and the United States may, of course, come

into court to prove that exceptional circumstances com

pel modification of the decree. For example, school

systems in areas which let school out during planting

and harvesting seasons may find that the period for

exercise of choice of school, March 1-31, should be

changed to a different month. (Slip Opinion, pp.

111- 12)1

Motion for Summary Judgment

1 The choice period is May 1—June 1 in the year 1967.

8

2. In view of the decision, certain standards regarding

the exercise of choice in a free choice plan are required

in all school cases pending in this Circuit, including the,

present case. Those standards include the necessity for

an adequate period of time for the choice period, the re

quirement that all pupils in the system exercise a choice,

and certain other matters as set out more fully below in

the prayer for relief.

3. I f the requested motion is not granted and the re

quired free choice period is not established immediately

by order of this Court, the rights of the plaintiffs as estab

lished by the decision of the Fifth Circuit will be seriously

jeopardized as far as the coming school year is concerned.

4. In view of the fact that the plan presently in effect

in this case does not fully conform to the standards set

out by the Fifth Circuit and in view of the Fifth Circuit’s

holding that as a matter of law its proposed decree is to

be entered in all pending cases except where exceptional

circumstances are shown to exist, there are no material

questions of fact at issue and plaintiffs are entitled to

judgment as a matter of law. Therefore, this Court should

grant the requested motion for summary judgment pur

suant to F.R.C.P. Rule 56 and render the decree sought

herein by the plaintiffs.

W herefore, plaintiffs pray for summary judgment, after

defendants have been given an opportunity to respond a ̂

provided for in Rule 56, granting an order requiring the

school board to amend the plan presently in effect in the

following particulars, as required by the proposed decree

of the Fifth Circuit in the above-mentioned cases (Slip

Opinion, pp. 118-25; 132-34) :

Motion for Summary Judgment

9

I

S peed of D esegregation

Commencing with, the 1967-68 school year, in accordance

with this decree, all grades, including kindergarten grades,

shall be desegregated and pupils assigned to schools in

these grades without regard to race or color.

II

E xercise of C hoice

The following provisions shall apply to all grades:

(a) Who May Exercise Choice. A choice of schools may

be exercised by a parent or other adult person serving as

the student’s parent. A student may exercise his own

choice if he (1) is exercising a choice for the ninth or a

higher grade, or (2) has reached the age of fifteen at the

time of the exercise of choice. Such a choice by a student

is controlling unless a different choice is exercised for him

by his parent or other adult person serving as his parent

during the choice period or at such later time as the student

exercise a choice. Each reference in this decree to a stu

dent’s exercising a choice means the exercise of the choice,

as appropriate, by a parent or such other adult, or by the

student himself.

(b) Annual Exercise of Choice. All students, both white

and Negro, shall be required to exercise a free choice of

schools annually.

(c) Choice Period. The period for exercising choice

shall commence May 1, 1967 and end June 1, 1967, and

in subsequent years shall commence March 1 and end

March 31 preceding the school year for which the choice

Motion for Summary Judgment

10

is to be exercised. No student or prospective student who

exercises his choice within the choice period shall be given

any preference because of the time within the period when

such choice was exercised.

(d) Mandatory Exercise of Choice. A failure to exercise

a choice within the choice period shall not preclude any

student from exercising a choice at any time before he

commences school for the year with respect to which the

choice applies, but such choice may be subordinated to the

choices of students who exercised choice before the ex

piration of the choice period. Any student who has not

exercised his choice of school within a week after school

opens shall be assigned to the school nearest his home

where space is available under standards for determining

available space which shall be applied uniformly through

out the system.

(e) Public Notice. On or within a week before the date

the choice period opens, the defendants shall arrange for

the conspicuous publication of a notice describing the pro

visions of this decree in the newspaper most generally

circulated in the community. The text of the notice shall

be substantially similar to the text of the explanatory

letter sent home to parents. (See paragraph 11(e).) Pub

lication as a legal notice will not be sufficient. Copies of

this notice must also be given at that time to all radio and

television stations serving the community. Copies of this

decree shall be posted in each school in the school system

and at the office of the Superintendent of Education.

(f) Mailing of Explanatory Letters and Choice Forms.

On the first day of the choice period there shall be dis

tributed by first-class mail an explanatory letter and a

Motion for Summary Judgment

11

choice form to the parent (or other adult person acting

as parent, if known to the defendants) of each student, to

gether with a return envelope addressed to the Super

intendent. Should the defendants satisfactorily demon

strate to the court that they are unable to comply with the

requirement of distributing the explanatory letter and

choice form by first-class mail, they shall propose an alter

native method which will maximize individual notice, i.e.,

personal notice to parents by delivery to the pupil with

adequate procedures to insure the delivery of the notice.

The text for the explanatory letter and choice form shall

essentially conform to the sample letter and choice form

appended to this decree. (See Appendix A.)

(g) Extra Copies of the Explanatory Letter and Choice

Form. Extra copies of the explanatory letter and choice

form shall be freely available to parents, students, prospec

tive students, and the general public at each school in the

system and at the office of the Superintendent of Education

during the times of the year which such schools are usually

open.

(h) Content of Choice Form. Each choice form shall set

forth the name and location of the grades offered at each

school and may require of the person exercising the choice

the name, address, age of student, school and grade cur

rently or most recently attended by the student, the school

chosen, the signature of one parent or other adult person

serving as parent, or where appropriate the signature of

the student, and the identity of the person signing. No

statement of reasons for a particular choice, or any other

information, or any witness or other authentication, may

be required or requested, without approval of the court.

(See Appendix B.)

Motion for Summary Judgment

1 2

(i) Return of Choice Form. At the option of the person

completing the choice form, the choice may be returned

by mail, in person, or by messenger to any school in the/

school system or to the office of the Superintendent.

(j) Choices not on Official Form. The exercise of choice

may also be made by the submission in like manner of any

other writing which contains information sufficient to iden

tify the student and indicates that he has made a choice

of school.

(k) Choice Forms Binding. When a choice form has

once been submitted and the choice period has expired,

the choice is binding for the entire school year and may

not be changed except in cases of parents making different

choices from their children under the conditions set forth

in paragraph 11(a) of this decree and in exceptional cases

where, absent the consideration of race, a change is edu

cationally called for or where compelling hardship is shown

by the student.

(l) Preference in Assignment. In assigning students to

schools, no preferences shall be given to any student for

prior attendance at a school and, except with the approval

of court in extraordinary circumstances, no choice shall be

denied for any reason other than overcrowding. In case

of overcrowding at any school, preference shall be given

on the basis of the proximity of the school to the homes

of the students choosing it, without regard to race or color.

Standards for determining overcrowding shall be applied

uniformly throughout the system.

(m) Second Choice where First Choice is Denied. Any

student whose choice is denied must be promptly notified

Motion for Summary Judgment

13

in writing and given Ms choice of any school in the school

system serving his grade level where space is available.

The student shall have seven days from the receipt of no

tice of a denial of first choice in which to exercise a second

choice.

(n) Official not to Influence Choice. At no time shall any

official, teacher, or employee of the school system influence

any parent, or other adult person serving as a parent, or

any student, in the exercise of a choice or favor or penalize

any person because of a choice made. I f the defendant

school board employs professional guidance counsellors,

such persons shall base their guidance and counselling on

the individual student’s particular personal, academic, and

vocational needs. Such guidance and counselling by teach

ers as well as professional guidance counsellors shall be

available to all students without regard to race or color.

(o) Protection of Persons Exercising Choice. Within

their authority school officials are responsible for the pro

tection of persons exercising rights under or otherwise

affected by this decree. They shall, without delay, take

appropriate action with regard to any student or staff

member who interferes with the successful operation of

the plan. Such interference shall include harassment, in

timidation, threats, hostile words or acts, and similar be

havior. The school board shall not publish, allow, or cause

to be published, the names or addresses of pupils exer

cising righst or otherwise affected by this decree. I f offi

cials of the school system are not able to provide sufficient

protection, they shall seek whatever assistance is necessary

from other appropriate officials.

Motion for Summary Judgment

14

III

P rospective S tudents

Each prospective new student shall be required to exer

cise a choice of schools before or at the time of enrollment.

All such students known to defendants shall be furnished

a copy of the prescribed letter to parents, and choice form,

by mail or in person, on the date the choice period opens

or as soon thereafter as the school system learns that he

plans to enroll. Where there is no pre-registration proce

dure for newly entering students, copies of the choice forms

shall be available at the Office of the Superintendent and

at each school during the time the school is usually open.

IV

T ransfers

(a) Transfers for Students. Any student shall have the>

right at the beginning of a new term to transfer to any

school from which he was excluded or would otherwise be

excluded on account of his race or color.

(b) Transfers for Special Needs. Any student who re

quires a course of study not offered at the school to which

he has been assigned may be permitted, upon his written

application, at the beginning of any school term or semester,

to transfer to another school which offers courses for his

special needs.

(c) Transfers to Special Classes or Schools. I f the de

fendants operate and maintain special classes or schools

for physically handicapped, mentally retarded, or gifted

children, the defendants may assign children to such schools

or classes on a basis related to the function of the special

class or school that is other than freedom of choice. In no

Motion for Summary Judgment

15

event shall such assignment be made on the basis of race

or color or in a manner which tends to perpetuate a dual

school sysetm based on race or color.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack G reenberg

Charles S teph en R alston

H enry M . A ronson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Motion for Summary Judgment

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the fore

going Motion for Summary Judgment on the defendants

by mailing a copy of the same to their attorneys, J. Madden

Hatcher, Esq., and A. J. Land, Esq., P. 0. Box 469, Colum

bus, Georgia, by United States mail, postage prepaid.

Done this 30th day of January, 1967.

H oward M oore, Jr.

Attorney for Plaintiffs;

16

APPENDIX A

Explanatory Letter

(School System Name and Office Address)

(Date Sent)

Dear Parent:

All grades in onr school system will be desegregated next

year. Any student who will be entering one of these grades

next year may choose to attend any school in our system,

regardless of whether that school was formerly all-white

or all-Negro. It does not matter which school your child

is attending this year. You and your child may select any

school you wish.

Every student, white and Negro, must make a choice of

schools. If a child is entering the ninth or higher grade, or

if the child is fifteen years old or older, he may make the

choice himself. Otherwise a parent or other adult serving

as parent must sign the choice form. A child enrolling in

the school system for the first time must make a choice of

schools before or at the time of his enrollment.

The form on which the choice should be made is attached

to this letter. It should be completed and returned by June

1, 1967. You may mail it in the enclosed envelope, or de

liver it by messenger or by hand to any school principal or

to the Office of the Superintendent at any time between

May 1 and June 1. No one may require you to return your

choice form before June 1 and no preference is given for

returning the choice form early.

No principal, teacher or other school official is permitted

to influence anyone in making a choice or to require early

return of the choice form. No one is permitted to favor or

17

Appendix A

penalize any student or other person because of a choice

made. A choice once made cannot be changed except for

serious hardship.

No child will be denied his choice unless for reasons of

overcrowding at the school chosen, in which case children

living nearest the school will have preference.

Transportation will be provided, if reasonably possible,

no matter what school is chosen. [Delete if the school sys

tem does not provide transportation.]

Your School Board and the school staff will do every

thing we can to see to it that the rights o f all students are

protected and that desegregation of our schools is carried

out successfully.

Sincerely yours,

Superintendent

18

APPENDIX B

Choice Form

This form is provided for you to choose a school for

your child to attend next year. You have 30 days to make

your choice. It does not matter which school your child

attended last year, and does not matter whether the school

you choose was formerly a white or Negro school. This

form must be mailed or brought to the principal of any

school in the system or to the office of the Superintendent,

[address], by June 1, 1967. A choice is required for each

child.

Name of Child ......... .................................. .................................. ,

(Last) (First) (Middle)

A ddress................................................................

Name of Parent or other

adult serving as parent .................................

I f child is entering first grade, date of birth

(Month) (Day) (Year)

Grade child is entering

School attended last year

19

Appendix B

Choose one of the following schools by marking an X beside

the name.

Name of School Grade Location

Signature

Date

To be filled in by Superintendent:

School Assigned

2 0

Motion to Allow Appearance of Counsel

(Filed February 1, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

H oward M oore, J r ., E sq., moves the Court for an order

allowing his appearance as counsel for the plaintiffs in the

above case.

This 30th day of January, 1967.

H oward M oore, J r .

8591/s Hunter St., N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

21

Order

Upon consideration of the above and foregoing motion

to allow appearance of counsel, the same is hereby allowed

and ordered filed and the clerk is directed to enter the name

of Howard Moore, Jr., as counsel of record for the plain

tiffs.

This 1st day of February, 1967.

J . R obert E lliott

Judge, United States District Court

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the fore

going motion on defendants by mailing a copy of same to

their attorney, J. Madden Hatcher, Esq., P. O. Bos 469,

Columbus, Georgia, via United States Mail, postage pre

paid.

This 30th day of January, 1967.

H oward M oore, Jr.

22

Notice of Motion

(Filed February 17, 1967)

(Caption Omitted)

To:

J. Madden Hatcher, Esq. and A. J. Land, Esq., P. 0. Box

469, Columbus, Georgia, attorneys for defendant Board of

Education of Muscogee County School District, Georgia,

et al.

You and each of you are hereby notified that the under

signed counsel for movants herein will bring the attached

motion for further relief, together with the herein before

filed motion for summary judgment, on for hearing at such

time and place as the court shall order or, in the event no

order for hearing is allowed, within 15 days of the receipt

of the same, on briefs, as provided for in the “local rules of

court” . You are invited to appear and take such part as

you consider fit and proper.

This 15th day of February, 1967.

H oward M oore, Jr.

859% Hunter St., N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorney for Movants

23

(Filed February 17, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

Plaintiffs, by their undersigned attorneys, hereby move

this Court for further relief in this case, and in support of

such motion, would show the following:

1. On December 29, 1966, the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit rendered its decision in the

case of the United States of America and Linda Stout v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., No. 23345, and

six companion school cases. In that decision the Fifth Cir

cuit settled a number of important issues regarding the re

quirements of plans for school desegregation in this Cir

cuit. The plaintiffs have already filed a motion for sum

mary judgment in this case for an order granting them a

number of the requirements set out by the Fifth Circuit

regarding which no taking of evidence is necessary.

2. In addition to the matters covered in plaintiffs’ motion

for summary judgment, the Fifth Circuit also made it clear

that all plans in this Circuit for the desegregation of schools

are to include provisions: that will insure that services,

facilities, activities and programs in all schools will be free

of segregation and discrimination; that in all schools here

tofore maintained for Negro students, the school boards

must take prompt steps to equalize the physical facilities',

equipment, courses of instruction, etc., if such steps are

necessary; that the school boards are to locate any planned

new schools wtih the objective of eradicating any vestiges

of the former dual school system and to eliminate the ef

fects of segregation; that the school boards are to take

prompt steps to achieve substantial desegregation of school

Motion for Further Relief

24

faculties for the school year 1967-68; and that school boards

are to file with the district court and serve upon plaintiffs

comprehensive reports setting out the extent of desegrega

tion.

3. Since the plan presently in effect in the present case

does not fully conform to the standards set out by the Fifth

Circuit, plaintiffs are entitled to a further order establish

ing a plan that provides for the above-mentioned matters.

W herefore, plaintiffs pray that this Court set down this

motion for hearing and, after such hearing, grant an order

requiring the school board to amend to the extent necessary

the plan presently in effect in the following particulars, as

required by the proposed decree of the Fifth Circuit in the

above-mentioned case (Slip Opinion, pp. 126-131):

I

S ervices, F acilities, A ctivities and P rograms

No student shall be segregated or discriminated against

on account of race or color in any service, facility, activity,

or program (including transportation, athletics, or other

extra-curricular activity) that may be conducted or spon

sored by or affiliated with the school in which he is enrolled.

A student attending school for the first time on a desegre

gated basis may not be subject to any disqualification or

waiting period for participation in activities and programs,

including athletics, which might otherwise apply because

he is a transfer or newly assigned student except that such

transferees shall be subject to long-standing, non-racially

based rules of city, county, or state athletic associations

dealing with the eligibility of transfer students for athletic

contests. All school use or school-sponsored use of athletic

Motion for Further Relief

25

fields, meeting rooms, and all other school related services,

facilities, activities, and programs such as Commencement

exercises and parent-teacher meetings which are open to

persons other than enrolled students, shall be open to all

persons without regard to race or color. All special educa

tional programs conducted by the defendants shall be con

ducted without regard to race or color.

II

S chool E qualization

(a) Inferior Schools. In schools heretofore maintained

for Negro students, the defendants shall take prompt steps

necessary to provide physical facilities, equipment, courses

of instruction, and instructional materials of quality equal

to that provided in schools previously maintained for white

students. Conditions of overcrowding, as determined by

pupil-teacher ratios and pupil-classroom ratios shall, to the

extent feasible, be distributed evenly between schools for

merly maintained for Negro students and those formerly

maintained for white students. If for any reason it is not

feasible to improve sufficiently any school formerly main

tained for Negro students, where such improvement would

otherwise be required by this subparagraph, such school

shall be closed as soon as possible, and students enrolled in

the school shall be reassigned on the basis of freedom of

choice. By October of each year, defendants shall report to

the Clerk of the Court pupil-teacher ratios, pupil-classroom

ratios, and per-pupil expenditures both as to operating and

capital improvement costs, and shall outline the steps to be

taken and the time within which they shall accomplish the

equalization of such schools.

(b) Remedial Programs. The defendants shall provide

remedial education programs which permit students attend

Motion for Further Belief

Motion for Further Belief

ing or who have previously attended all-Negro schools to

overcome past inadequacies in their education.

III

N ew C onstruction

The defendants, to the extent consistent with the proper

operation of the school system as a whole, shall locate any

newT school and substantially expand any existing schools

with the objective of eradicating the vestiges of the dual

system and of eliminating the effects of segregation.

IV

F aculty and S taee

(a) Faculty Employment. Race or color shall not be a

factor in the hiring, assignment, reassignment, promotion,

demotion, or dismissal of teachers and other professional

staff members, including student teachers, except that race

may be taken into account for the purpose of counteracting

or correcting the effect of the segregated assignment of

teachers in the dual system. Teachers, principals, and staff

members shall be assigned to schools so that the faculty and

staff is not composed exclusively of members of one race.

Wherever possible, teachers shall be assigned so that more

than one teacher of the minority race (white or Negro)

shall be on a desegregated faculty. Defendants shall take

positive and affirmative steps to accomplish the desegrega

tion of their school faculties and to achieve substantial de

segregation of faculties in as many of the schools as pos

sible for the 1967-68 school year notwithstanding that

teacher contracts for the 1966-67 or 1967-68 school years

may have already been signed and approved. The tenure

of teachers in the system shall not be used as an excuse for

27

failure to comply with, this provision. The defendants shall

establish as an objective that the pattern of teacher assign

ment to any particular school not be identifiable as tailored

for a heavy concentration of either Negro or white pupils

in the school.

(b) Dismissals. Teachers and other professional staff

members may not be discriminatorily assigned, dismissed,

demoted, or passed over for retention, promotion, or re

hiring, on the ground of race or color. In any instance where

one or more teachers or other professional staff members

are to be displaced as a result of desegregation, no staff

vacancy in the school system shall be filled through recruit

ment from outside the system unless no such displaced staff

member is qualified to fill the vacancy. If, as a result of de

segregation, there is to be a reduction in the total profes

sional staff of the school system, the qualifications of all

staff members in the system shall be evaluated in selecting

the staff member to be released without consideration of

race or color. A report containing any such proposed dis

missals, and the reasons therefor, shall be filed with the

Clerk of the Court, serving copies upon opposing counsel,

within five (5) days after such dismissal, demotion, etc., as

proposed.

(c) Past Assignments. The defendants shall take steps

to assign and reassign teachers and other professional staff

members to eliminate past discriminatory patterns.

V

R eports to th e C ourt

(1) Report on Choice Period. The defendants shall serve

upon the opposing parties and file with the Clerk of the

Court on or before April 15, 1967, and on or before June

Motion for Further Relief

Motion for Further Belief

15, 1967, and in each subsequent year on or before June 1,

a report tabulating by race the number of choice applica

tions and transfer applications received for enrollment in

each grade in each school in the system, and the number

of choices and transfers granted and the number of denials

in each grade of each school. The report shall also state

any reasons relied upon in denying choice and shall

tabulate, by school and by race of student, the number of

choices and transfers denied for each such reason.

In addition the report shall show the percentage of

pupils actually transferred or assigned from segregated

grades or to schools attended predominantly by pupils of a

race other than the race of the applicant, for attendance

during the 1966-67 school year, with comparable data for

the 1965-66 school year. Such additional information shall

be included in the report served upon opposing counsel and

filed with the Clerk of the Court.

(2) Report After School Opening. The defendants shall,

in addition to reports elsewhere described, serve upon op

posing counsel and file with the Clerk of the Court within

15 days after the opening of schools for the fall semester

of each year, a report setting forth the following informa

tion:

(i) The name, address, grade, school of choice and

school of present attendance of each student who has

withdrawn or requested withdrawal of his choice of

school or who has transferred after the start of the

school year, together with a description of any action

taken by the defendants on his request and the reasons

therefor.

(ii) The number of faculty vacancies, by school, that

have occurred or been filled by the defendants since

29

the order of this Court or the latest report submitted

pursuant to this subparagraph. This report shall state

the race of the teacher employed to fill each such va

cancy and indicate whether such teacher is newly em

ployed or was transferred from within the system.

The tabulation of the number of transfers within the

system shall indicate the schools from which and to

which the transfers were made. The report shall also

set forth the number of faculty members of each race

assigned to each school for the current year.

(iii) The number of students by race, in each grade

of each school.

Respectfully submitted,

H oward M oore, J r .

859]/2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

C harles S teph en R alston

H en ry M . A ronson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Motion for Further Relief

30

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the forego

ing Motion for Further Relief on the defendants by mail

ing a copy of the same to their attorneys, J. Madden

Hatcher, Esq., and A. J. Land, Esq., P. 0. Box 469, Colum

bus, Georgia, by United States mail, postage prepaid.

Done this 15th day of February, 1967.

H ow ard M oore , J r .

Attorney for Plaintiffs

31

Notice of Motion

(Filed May 9, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

To:

J. Madden Hatcher, Esq. and A. J. Land, Esq., P. 0. Box

469, Columbus, Georgia, attorneys for defendant Board of

Education of Muscogee County School District, Georgia,

et al.

You and each of you are hereby notified that the under

signed counsel for movants herein will bring the attached

motion on for hearing at such time and place as the Court

shall order or, in the event no order for hearing is allowed,

within fifteen days of the receipt of the same, on briefs, as

provided for in the “Local Rules of Court” . You are in

vited to appear and take such part as you consider fit and

proper.

This 6th day of May, 1967.

H oward M oore, J r .

859% Hunter St., N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorney for Movants

32

Motion for an Order Entering a Decree on the Authority

of the U n ite d S ta tes o f A m e r ic a a n d L in d a S to u t v.

J e ffe r s o n County B o a r d o f E d u c a tio n , e t a l ., or in

the Alternative, for an immediate Hearing

(Filed May 9, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

Plaintiffs, by their undersigned attorneys, hereby move

this Court for an order entering a decree on the authority

of the United States of America and Linda Stout v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, et al., No. 23345, decided

December 29, 1966 in the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit, or in the alternative, for an immedi

ate hearing. In support of such motion, plaintiffs show the

following:

1. The decision of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit on December 29, 1966 by three judges

of said Court was affirmed by the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit sitting en banc. Motions for

stays of execution and enforcement are the judgments of

the United States District Court for the Eastern and West

ern Districts of Louisiana entered pursuant to the man

dates of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in said cases were denied by the Supreme Court

of the United States on April 17, 1967, sub nom. Caddo

Paris School Board v. United States, 35 U. S. Law Week,

3365 (1967).

2. The record, orders, judgments, decrees, and plans of

filed in this Court in the above captioned case clearly show

that the plan now providing for limited equal educational

opportunities in the school system operated by the defend

ant Board of Education of Muscogee County School Dis-

33

Motion for an Order Entering a Decree on the Authority

of the United States of America and Linda Stout v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., or in

the Alternative, for an immediate Hearing

trict does not satisfy the judgments and mandates of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

the case of the United States of America, and Linda Stout

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al., No. 23345.

W herefore, plaintiffs pray that this Court enter an order

decreeing the defendant School Board to amend to the ex

tent necessary the plan presently in effect so as to fully

conform to the standards set out by the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit or, in the alternative, to

set down their previously filed motions for summary judg

ment and for further relief for hearing and, after such hear

ing, grant an order requiring the school board to amend

to the extent necessary the plan presently in effect to fully

conform to the standards set out by the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

H oward M oore, J r .

859y2 Hunter St., N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

J ack G reenberg

C harles S teven It Alston

H enry M . A ronson

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

34

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the fore

going motion on the defendants by filing a copy of the same

to their attorneys, J. Madden Hatcher, Esq., and A. J. Land,

Esq., P. 0. Box 469, Columbus, Georgia, by United States

Mail, postage prepaid.

Done this 6th day of May, 1967.

H ow ard M oore, J r .

Attorney for Plaintiffs

35

Response o f Defendant to Plaintiffs’ Motion for an Order

Entering a Decree on the Authority o f the United

Slates o f America, el al. v. Jefferson County Board

o f Education, et al.

(Filed June 6, 1967)

[Caption Omitted]

Comes now the Defendant, B oard of E ducation of th e

M uscogee C ou nty S chool D istrict of th e S tate of Georgia,

and, in response to the motion of the Plaintiffs served on

the Defendant May 6, 1967, respectfully shows to the Court

as follows:

1.

Defendant is informed and believes that the School Board

defendants in the case of United States of America and

Linda Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, et al.,

No. 23345, have petitioned, or will in the near future peti

tion, for certiorari to the Supreme Court of the United

States to have the decree entered in the above stated case

in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit on December 29,1966, reviewed, reversed and remanded,

and such petition for certiorari has not yet been granted or

denied by the Supreme Court, and the decree of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in the above

stated case should not be considered final until said petition

for certiorari has been acted upon.

2.

This Defendant, prior to the filing of this suit by the

Plaintiffs, did on September 16, 1963, adopt a plan to de

segregate the schools of the Muscogee County School Dis

trict, Georgia, and, since the adoption of said plan, have

36

persistently prosecuted the desegregation of said School

System and did on December 28, 1964, an on December 20,

1965, and on January 31, 1967, amend said plan so that said

schools could he desegregated as rapidly as reasonably pos

sible. In accordance with the judgment of this Court and

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in this case, Defendant has given the par

ents of each student in each grade, including Kindergarten,

the free choice to select the school which said parents desire

for said student to attend during the next school year, and

all choice applications have been acted upon by the Super

intendent and his staff without reference to race or color,

and all of said applications have been granted or acted

upon in a manner satisfactory to said parents and students

and there has been no appeal filed by any parent or student

with respect to any choice application.

3.

All of the schools and grades in the Muscogee County

School System have been accredited by the Southern Ac

crediting Association, and Defendant is affording each and

every child as fine an educational opportunity as the funds

available to it will permit.

Response of Defendant to Plaintiffs’ Motion, etc.

4.

The actions of this Defendant in administering said

schools and said plan of desegregation has met with the

approval of the Citizens of this County.

5.

Defendant has desegregated the faculties in some of the

classes and schools in its system.

37

6.

Defendant respectfully submits that the plan for the

desegregation of the schools of the Muscogee County School

District as now in effect and as now being carried out con

forms as nearly to the standards set out in the Jefferson

County case as is possible, consistent with the Defendant’s

duty to furnish quality education to the school children of

its District.

7.

To require the Muscogee County School District to

amend its plan to include all of the requirements which

were imposed upon the school districts in the Jefferson

County case would deprive the Board of Education of the

Muscogee County School District of the discretion and

flexibility necessary to give to every person true freedom

to attend the school of his choice and will necessarily result

in causing many students to attend schools other than that

of their choice.

8.

Defendant shows that imposing upon the Defendant of

all of the requirements imposed upon the school districts

involved in the Jefferson County case would drastically

affect the Defendant’s opportunity to furnish quality edu

cation to all school children in this County, and Defendant

should not be required so to do.

9.

Defendant shows that during the month of March, 1967,

all persons were given the opportunity to designate the

school of their choice; that all teacher contracts and as

signments for the coming year have been completed; that

Response of Defendant to Plaintiffs’ Motion, etc.

38

the faculties of each school have been organized; and that

it would be extremely costly and administratively burden

some to undertake to comply with such decree with respect

to the coming school year.

W herefore, Defendant prays that this Court approve its

plan of desegregation and the acts and efforts of this De

fendant in administering the same and permit it to con

tinue to operate the schools of this County so long as its

efforts in good faith seek to fully comply with the Constitu

tion of the United States and satisfy substantially all of

the citizens of this County.

J. M adden H atcher

A. J. L and

Attorneys for Defendant

Address:

P. 0. Box 469

Columbus, Georgia

Columbus, Georgia

I, J. M adden H atcher , hereby certify that I am one of

the attorneys for the Defendant in the foregoing case and

that I have this day served the foregoing response on the

Plaintiffs by placing true copies thereof in sealed wrappers,

with postage prepaid, addressed to Howard Moore, Jr.,

Esquire, 859V2 Hunter St., N. W., Atlanta, Georgia 30314,

and to Jack Greenberg, Esquire, Charles Steven Ralston,

Esquire, and Henry M. Aronson, Esquire, Suite 2030, 10

Columbus Circle, New York, New York 10019, the attorneys

for Plaintiffs, and depositing the same in a United States

mailbox.

This 5th day of June, 1967.

J. M adden H atcher

Response of Defendant to Plaintiffs’ Motion, etc.

39

Transcript of Proceedings

[Caption Omitted]

P residing

H onorable J. R obert E llio tt ,

United States District Judge

At: Columbus, Georgia,

9:30 A. M., June 15, 1967.

A p p e a r a n c e s :

For Plaintiffs:

M r. Charles S teph en R alston ,

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, N. Y. 10019.

M r. C. B. K ing ,

P. 0. Box 1024, Albany, Ga.

For Defendants:

H atcher , S tubbs, L and & R oth schild ,

P. O. Box 469, Columbus, Ga.,

Mr. J. M adden H atcher and

M r. A . J. L and , of cousel.

R e p o r t e d B y

Claude J oiner, Jr.,

Official Reporter, U. S. Court,

Middle District of Georgia,

P. O. Box 94, Macon, Ga.

— 1 —

C olum bus, Ga. 9:30 A. M. J un e 15, 1967

The Court: We have set down for hearing at this time

motion or motions pending in Civil Action No. 991 of the

40

Columbus Division of the Court, Lockett, et al. versus

Board of Education of Muscogee County School District,

and so forth. Do you announce ready for the Plaintiff, Mr.

King?

Mr. King: Your Honor pleases, we announce ready.

The Court: Allright, Mr. Hatcher, do you announce

ready for the Defendant?

Mr. Hatcher: I f the Court pleases, in that connection, I

would like to ask the Court and suggest that in light of the

Jefferson case and also the decision of the Fifth Circuit in

the Bibb County case suggest to us that the burden is on

the respondent School Board to show why the relief

prayed for should not be granted, and we would like to

assume that burden, and would like to open and conclude.

The Court: AH right.

Mr. Hatcher: We are ready.

The Court: All right, you may proceed.

Dr. Wm. II. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

Dr. W m . H. S h a w , called as witness by Defendants, being

duly sworn, testified on

—2—

Direct Examination by Mr. Hatcher:

Q. Dr. Shaw, please your full name, your age, your

residence and your occupation? A. I ’m W. H. Shaw, Pm

64 years old; I reside at 2870 Cromwell Drive, and I ’m

Superintendent of Education for the Muscogee County

School District.

Q. How long have you been Superintendent of the schools

in Muscogee County? A. Since September 1, 1945.

Q. Will you state just briefly what your educational qual

ifications are? A. I have the A. B. and the Master from

41

Duke University, a sis year graduate in administration

from Teachers College, Columbia, and the Doctorate Degree

from Auburn University in school administration and

supervision.

Q. Please state in a summary manner the growth of the

schools in this County since you have come to Columbus?

A. As you know, the County and the City were separate

when I came here in September, ’45, but the combined en

rollment for the two systems at that time was 19,930, with

48 schools. They were merged on the 1st of January, 1950

and now the enrollment as of June 2, total enrollment for

the year was 49,384, with 64 buildings housing the pupils.

—3—

Q. What percentage of the total enrollment is Negro?

A. Based on the figures I have just quoted you there, 27.5

are Negro and 72.5 are white.

Q. Are all of the classes in each of the public schools in

Muscogee County accredited? A. Yes, all of the high

schools have been accredited beginning with Columbus

High in 1913; and all of the junior high schools were ac

credited—and this is by the State and by the Southern

Association of Colleges and Schools—all of the junior high

schools were accredited in 1965; and last November all 49

of the elementary schools were accredited by the Southern

Association of Colleges and Schools as a system. We didn’t

pick out individual schools. We could have take an indi

vidual school here and one there but the School Board

elected to accredit the whole system, and we waited until we

could do that.

Q. Is it rather unusual for a whole system to be accredited

at one time in big city systems like this? A. Well, it is

difficult to the extent that many of them just pick out certain

Dr. Wm. II. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

42

schools and have them accredited. Some that tried to get

the whole system accredited last November by the Southern

Association failed to do so and then they took certain

schools in their system. But we said from the beginning if

—4-—

we couldn’t have them all accredited, we wouldn’t have any

accredited.

Q. What expense was incurred by the School System to

bring the System up to the standards required for accredi

tation! A. It is a little bit difficult but I will give you an

example here so that you may have for your own self

some basis for deciding that it is an expensive thing to meet

accreditation standards.

Preparation for accrediation took place over a three year

period, that is of the elementary schools. In ’63 the total

budget for the School District was $10,470,020. The schools

were accredited in November, ’66, and for the school year

’66-67 the total budget for the Muscogee County School Dis

trict was $15,699,296, or an increase during this three year

period of $5,292,276. Of course, part of this increase would

be due to the increased enrollment but a great portion of it

was due to the increase in teacher salaries and the change

in the number of pupils per teacher, lowering the number

to 1 to 28 in the elementary and 1 to 25 in the junior and

senior high schools. $300,000, as an example, $300,000

was spent for library books, in order to conform to the one

standard requiring 9 books per pupil.. This is just an ex

ample of how the expense had to be increased.

— 5—

Q. Was there any school room in any school in the Mus

cogee County School District objected to or condemned by

the Accrediting Association as now meeting the standards

Dr. Wm. II. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

43

of the Association-?A. No; no, we did not fail; we had to

meet all of the criteria and we did not fail to meet any of

the standards.

Q. When was a plan to desegregate the schools in Mus

cogee County first adopted? A. It was adopted by the

Board of Education on September 16, 1963.

Q. At that time had any demand been made by anyone

or any suit filed to desegregate the schools? A. No.

Q. Under the plan of this System, as amended, state

whether or not the parents of all school children have been

given the opportunity to attend the school of their choice?

A. With the exception of 16 white parents and pupils, who

are still waiting and hoping that they can get a choice which

was their first choice, either Daniel or Arnold, all others

have been processed and so far as I know, they have been

accepted. Some did take second choices but they did that

willingly and without any complaint.

Q. When was the choice period for the school year com

mencing in September of this year? A. It was March 1

— 6—

through March 31 and we deviated that plan because the

Georgia Teachers and Education Association changed their

state teachers meeing by one week and moved it back to

Thursday and Friday, which would have interfered with

some orderly processing of filing the applications from the

all Negro schools; and so, we extended that through to

April 3, so as to give all of those an opportunity to over

come that handicap.

Q. Will you please state briefly or explain briefly the

plan or the method by which each child was given a choice

of schools? A. We first had a meeting of the Principals,

I believe on the 20th of February, and explained to them

in detail—I see some of my school principals in the audience

Dr. Wm. II. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

44

that would know this procedure—at an integrated Princi

pals’ meeting, and all of our Principals’ meetings have

been integrated since 1963. We explained in detail the

process for allowing the pupils to have these forms, to give

each pupil a form to take home for the parent to express

their choice of school for their child for the 1967-68 term.

We didn’t wait to anticipate how many forms would be

needed. We prepared by mimeograph process more than

43,000 forms and prepared them in sufficient bundles and

made them available to the Principals, to give every child

in their school two, a set of tw o; so that we could have a

— 7—

form and we could send a form to the parent after they

were approved.

They were announced, in the high schools, I believe, they

had assemblies, in home rooms they were announced; the

Principals all have a complete list of the schools, knowing

what grades were given in each school; and some parents

who failed to get a form came to our office, some called and

we mailed them to them; but in most cases we found that

a very high percentage—I would say 99 per cent.—of the

pupils took them home from the schools. Now, this is the

regular way for communicating with the parents in the

School District.

Q. What publicity was afforded through the press? A.

Well, the press is represented here today, they gave public

ity to the Board’s resolution providing for this complete

desegregation of our schools, which included the kinder

garten and grades 3, 4, 5 and 6, were the ones that had not

been desegregated; and under the Fifth Circuit court ap

proved plan, of the plan that had been previously approved

here in this District Court under Judge Elliott, we had until

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

45

1968. But on the 31st of January the Board voted to com

pletely desegregate the rest of the school pupils, all grades.

And I believe that everybody had an opportunity to know,

not only in the paid resolution published in the newspapers,

but also in front page stories, setting forth almost the

—8—

exact wording in the resolution adopted by the Board.

Q. What about in television and radio? A. Yes, I wit

nessed one evening news program, in which they read prac

tically verbatim the wording, and it was done several times,

and all the radios. We furnished copies of the resolution

to all of the news media, all of them.

Q. How many choice applications were received and

acted upon by the Superintendent and his staff? A. Those

received in our office, who were actually wanting to change

and choose a different school from the one they were in,

numbered 7,753; and, as I told you a moment ago, all but

16 of those have been finalized. Now, we passed on those

16; they are not in appeal; they are just hoping that their

first choice could still be carried out and, if it couldn’t, then

I ’m sure that they will accept the second choice that have

told them that they could have.

Q. Has there been any appeal filed with the School Board

as a result of any application? A. No.

Q. Has there been any complaint by anyone as a result

of any application? A. No, we had some inquiries to clar

ify a few things and they accepted it and there has been no

—not what I would consider a complaint no.

—9—

Q. How many teachers are there in the Muscogee County

School System? A. 1828 at the present time.

Q. How many Negro teachers are employed by such sys

tem? A. Even 500 of those are Negroes.

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

46

Q. Is there any difference in the pupil-teacher ratio in

any class in any school caused by or resulting from—

A. No, the same standard prevails for all of the Muscogee

County schools, 1 to 28 in the elementary and 1 to 25 in

the junior and senior high schools. We equalize those about

4 or 5 times a year. But Muscogee County, being a complete

school district, when people move— and there are certain

times of the year when they seem to move from one part

of the County to the other—-we find that sometimes the en

rollments will get a little bit out of line and then we im

mediately—we get a weekly report on every school, we im

mediately call those Principals and tell them to adminis

tratively shift some where they are more than the number

should be to the nearest school adjacent to them, if the

other school has room.

Now, we have some 8- to 9,000 pupils that are transients,

that move in and out of our County during the year, and

that gives us quite a bit of concern. About the time we

- 10-

get all of our enrollment equalized, here will come a great

number to Port Benning and a great number of those people

live in the County and, when they move into the County,

we are subject to having to take care of them at the nearest

school that they move to.

Q. Will all grades be desegregated in September of this

year, right? A. Yes, and the applications have been proc

essed to that point already.

Q. Now, state in detail the extent of faculty desegrega

tion in the Muscogee County School System? A. When you

use the word “detail” , Mr. Hatcher, it will take a little more

time—

Q. Yes sir. A. It will take a little bit more time than a

yes or no. Now, these first figures that I give you will re

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

47

late to the extent that faculty has been desegregated during

the regular term ending on June 2, and then I have a de

segregation of what is now going on in our schools in the

summer programs. I will leave that to last.

There is one Negro teacher at our Reading Center that

works with all children, regardless whether they are Negro

or white. They are bussed in from the different schools

according to their reading difficulty; once they have been

diagnosed as having a reading difficulty, they are sent in

— 11—

there. And they move—this teacher has a station and when

the children move from one teacher to the other, they are

all processed through her part of the diagnosis, her part of

this program, the Reading Center.

We have one Negro consultant in English. She works

mainly with English in the elementary schools.

In the Adult Education Program there is one part time

Negro teacher for both white and Negro students.

At Columbus Area Vocational Technical School, we have

one full time Negro, who conducts the work in guidance.

He works with all of the pupils who are enrolled in our

trade school.

Now, in case the Court is not familiar, we did have two

trade schools hut as of July, 1966, they were combined into

one school. There are two units but they are one school.

And there is a white teacher in Radio and TV, who is work

ing in what was formerly the all Negro trade school; and

another white teacher will go there on this July 1 because of

the growth in the enrollment of the classes in Radio and TV .

At the Instructional Material Center, there is one Negro

who works in audio-visual aids. He is not here this sum

mer; he is on leave with us to go to North Carolina State

at Durham, where he will improve his proficiency in work

ing with audio-visual aids.

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

Dr. Wm. H. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

— 12—

Now, here is the insert that I had for yon: In the sum

mer program we have a diagnostic reading center—-and

some of the little children call this the “ dognastie” reading

center—we have 8 white teachers and 3 Negro teachers

working there now. We have 4 white examiners and one

Negro examiner. We have 4 bus drivers, 4 white bus drivers

and 2 Negro bus drivers. We have 3 white clerks and one

Negro clerk. And all of this group are serving 722 white

pupils and 480 Negro pupils. The classes have been inte

grated with no regard for race. White teachers are teach

ing classes of all white children and white children and

Negro children, and some all Negro children, depending on

their reading needs according to the diagnostic tests. The

same is true for the Negro teachers who are working in

that Center.

Now, in our summer remedial program, that’s different

from the diagnostic center, there are 3 white Principals

and 2 Negro Principals. There are 38 white teachers and

34 Negro teachers. There are 840 white pupils and 600

Negro pupils. The pupils and teachers are distributed in

10 buildings: Radcliff, Manly Taylor, Talbotton Road, 30th

Avenue and Cusseta Road schools have only Negro pupils

because of the proximity to these centers, I suppose. How

ever, 4 Negro teachers and 5 white teachers are at 30th

Avenue and are working under a Negro Principal.

—13—

At Manly Taylor 5 Negro and 5 white teachers are

working under a Negro Principal.

Beallwood, Fox, East Highland, Daniel, Muscogee Ele

mentary find both white and Negro pupils with white

faculties.

49

At Radcliff it is supervised by a white principal, and

that is normally a Negro Center. There are 8 Negro teach

ers working in this Center under a white principal.

The tutoring program, which is new to us this summer,

where it is one person teaching one pupli, the tutoring

program employes 55 teachers. It enrolls 333 pupils at

12 school centers. Of the 55 teachers, 27 are Negro and

28 are white. At 3 of the 12 schools the faculties are inte

grated. At 9 schools the faculties are not integrated.

At Spencer, Baker, East Highlands and Radcliff schools

white teachers are tutoring Negro pupils.

Now, I have one other little part to that—I told you

when you asked for the word “detail” it would be a little

long, Mr. Hatcher. Beginning in September, ’63, all Prin

cipals’ meetings in the Muscogee County School District

were desegregated.

Beginning in June, 1966—that was a year ago—all

- 14-

general faculty meetings were desegregated. All group

faculty meetings for the purpose of studying curriculum

have been desegregated since September, ’66. We com

pletely rewrote and revised our curriculum and this was

done with integrated committees working on all subject

levels in the high schools and junior high schools, and in

all of the grade levels in the elementary schools.

Plans are currently underway and study has been made

by a joint committee of the Muscogee Education Associa

tion, the white organization, which is a private organiza

tion, and the Muscogee Teachers and Education Associa

tion, made up formerly of all Negro teacheis, looking to

ward the merging of the two professional organizations

into a single professional organization, which will become

a unit of the Georgia Education Association and the Na

Dr. Wm. II. Shaw—for Defendants—Direct

50

tional Education Association. And there is an article in

today’s paper saying that those meeting on the State level

have had some difficulty in agreeing on the details of the

plan for merger.

Now that, sir, covers just about the extent—

Q. What about the extra-curricular activities in the

School System at this time, the extent of desegregation,

in athletics and other activities? A. Well, once the school

was integrated, the pupils would have access and the priv

ilege to participate in any activity based on their ability

—15—

to meet whatever the requirements are to get into such an

organization by any pupil in the school.