Draft of Brief

Working File

January 1, 1980 - January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Draft of Brief, 1980. 1502c717-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e6cebe0-597e-46b8-a0e9-a42784ac2554/draft-of-brief. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

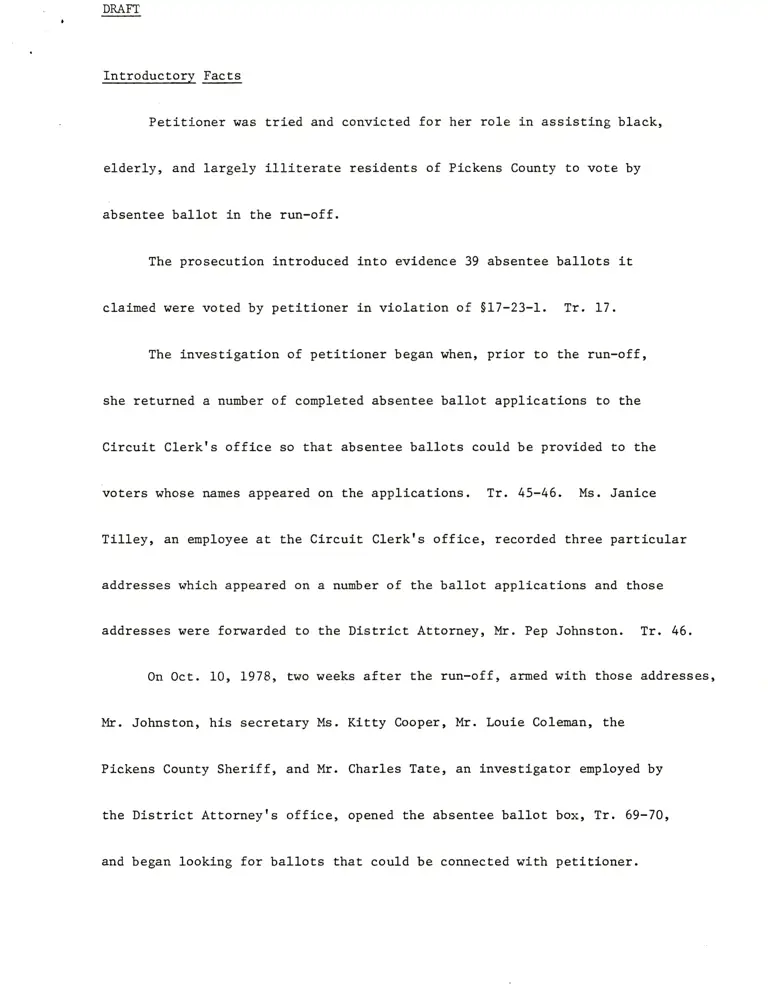

DRAFT

Introductory Facts

Petitioner was trled and convicted for her role in assisting bJ.ack,

elderly, and largely ilJ-iterate residents of Pickens County to vote by

absentee baLLot in the run-off.

The prosecution introduced into evidence 39 absentee ballots it

claj.med were voted by petitloner in violation of SL7-23-1. Tr. L7.

The investigatlon of petitioner began when, prior to the run-off,

she returned a number of completed absentee ballot applications to the

Clrcuit Clerkrs offlce so that absentee ballots could be provided to the

voters whose names appeared on the applications. Tr. 45-46. Ms. Janice

Tilley, an employee at the Clrcuit Clerkts office, recorded three particular

addresses which appeared on a number of the ballot appllcations and those

addresses were forwarded to the District Attorney, Ilr. Pep Johnston. Tr. 46.

On Oct. 10, 1978, two weeks after the run-off, armed wlth those addresses,

Mr. Johnston, hls secretary Ms. Kltty Cooper, Mr. Louie Colenan, the

Pickens County Sheriff, and Mr. Charles Tate, an lnvestigator empJ-oyed by

the District Attorneyts offi.ce, opened the absentee ballot box, Tr. 69-70,

and began looking for balLots that could be connected with petitioner.

Tr.

Using the three addresses taken off the absentee ballot application'

Mr. Tate opened and examined the appllcations, and recordecl the names of

voters whose ballots had been sent to one of the three addresses,

7O-7L, 75. The ballot box was then opened, and the absentee ballots

marked as being the balloLs of those voters arere examined, and lt was

notlced that alL of those ballots had been notarized by I'1r. Paul Rollins'

a notary public from Tuscaloosa, Tr. 58, 75-76. Then, alL of the ballots

notarized by Mr. RoLLins were isolated whether or not the appllcations

for each particular baLlot contained one of the three addresses. Id.

Thirty-nine absentee ballots were lsoLated ln this nanoer, Tr' 72' The

remalnder of the prosecutionts lnvestigatlon consisLed of interrogation

of Mr. Rollins and of a nuober of absentee voters in an effort to build

some sort of case against peti-tioner.

The Prosecutionrs Case Against Petitioner

As required by Jackson v. Vlrglnia, the evidence against Petitioner is

considered in the Llght most favorable to the ProsecutloB.

The testimony of Ms. Janice TiJ-l-ey, an employee at the Circuit Clerkrs

Offlce, in Pickens County, was that Petitioners plcked up a number of

-2-

absentee bal-Iot applications from Ehe Circuit Clerkrs Office during

week prior to Lhe run-off , Tr. 4O4. Us. TiJ-Iey also t,estifled that

peLltioner returned completed appllcations to the Circuit CLerkrs Office,

Tr. 45, and that petitioner deposited a number of absentee ballots on

the day before the run-off, Id. There is sinpl-y nothing criminal or

fraudul-ent about any of these actlvlties. The prosecutionts case against

petitioner must be buiLt entirel-y on other evidence.

I'Ir. RolJ-lns, the notary from Tuscaloosa, testified that petitloner

was present when the 39 balLots rrere notatLzed. Tr. L7. I"1r. Rollins

permltted petitloner to represent that the signltures on the absentee balLots

were genuine, Tr. 22, 25-27. Regardless of whether this was proper procedure,

it ls certainly not evidenee that petitloner was engaged ln fraudulent

activity. If anyone is at fault it is surely I,Ir. Rollins who allowed thls

procedure, and thereby represented to petltloDer that the procedure was a

proper means of notarizlng. CertalnJ-y it is reasonable that petltloner wouLd

rely on a notary for guidance as to proper notarizing procedures.

Testimony was given by 14 of the 39 voters whose balLots were introduced

into evidence. Their testimony 'rwas both confusing and conflictingr'l

-3-

Wilder v. State, 401- So.2d 151, ]-62 (Ala. Crin. App.), cert. denied,

454 U.S. 1057 (L982). As such, the testimony falJ-s far short of what

is necessary to convince a rational trier of fact that petitioner had

actually enployed fraud to procure absentee ballots from these voters.

Mr. Robert Goines, 87 years old at the tine of Lrial, Tr. 87, and

i1lJ.terate, Tr. 85, teseified that he voted in the run-off, Tr. 81. IIe

remembered also that petltioner had alded hin in filling out an applicatlon

for an absentee balLot, Tr. 82. Mr. Goines was Ehen asked whether he had

ever seen the absentee ballot voted ln his name to whlch he asnwered, "Yes,

sir, I belleve sorrr Tr. 83. Subseguently, after he was questloned on

whether he had cornpleted his absentee bal-l-ot without heI-p, Tr. 83-84, the

prosecutor returned to llr. Golnesf knowledge that an absentee ballot containing

his aame had been voted, uslng a different tact:

Q: Did you telL anybody they could vote for you on September the 26th,

L9 78.

/6'bjectlon from defense counsel, overrul-ed7

A. TeIl- anybody that I couLd get somebody to vote for me? You have to

do your orlrr voting.

a. That is what I thought, too. You did not tel-L anybody they could

vote for you.

/-D"f.n". counsel obj ectsT

A. I didn't do that. /6-bjection overruled-/ I have to go straight.

-4-

Q: You go by the rules?

I got to go straight. I didnrt do thaE.

Q: All right, sir. You did not vote thls balJ-ot, did you?

A: No str. I donrt know a thlng about this ball_ot.

Tr.84-85.

It was in this defensive context that Mr. Golaes changed his story fron the

memory he had professed of the ballot only moments before to this total-

disassociation. Mr. Goines obviously believed that his own conduct was at

issue, that any associatlon wlth the absentee ballot would indicate that

someone had voted for him, and that he had not rrgone by the rules.t'

Mr. Goines professed no memorll of the run-off, or of whether he voted tn that

of any election durlng 1978, Tr. 86. This complete about-face lndicates both

a lack of independent recollectlon as to the underlying events of the run-off,

and a Lack of understanding as to the meanlng of the questions being posed.

It is hconceivable that a rational trier of fact could credit testimony from

a witness under these circr.unstances.

Ms. Annle BIJ-Iups testified that petitioner aided her in filling out

the absentee bal-lot application, Tr. 92, aad ln completing the absentee bal-lot.

Tr.94-95.

Ms. Sophia Spann testlfied that she did not know what an absentee ballot

-5-

was, and that whenever she voted it was in person in Cochran, AJ-abarna,

Tr. 106. The absentee ba1lot appLication fll1ed out in Ms. Spannrs

petitioner. t,,s. Spannname had her name misspelled and was nitnessed by

testified that

e1se, Tr. L97.

petitioner, but

she had never spoken to petitioner about voting or anythlng

Viewed ln isoLation, Ms. Spannts testimony is harmful to

her testlmony must not be so viewed: Under Jackson, alL

of the evldence offered agalnst petitloner must be consldered.

Mr. Nat Dancy, 87 years old and i1-I-iterate, Tr. LzL, seemed to remember

that petltioner had brought some papers pertalning to voting to his home

at soDe tlme ln the past, Tr. L26. He testified at one point that petltioner

failed to explain absentee voting to him when she brought the papers per-

tainlng to votlng to his home, Tr. L23. But his answers throughout his

testimony were almost uniformly unresponsive. Ills answers revealed Lack of

understanding of the mechanics of voting, and a l-ack of any detailed

recollectlon of the events underJ-ying his vote in the run-off, to the

fact would not draw anyquestions posed by counsel. A rational trler of

conclusions from Mr. Dancyrs testimony.

Ms. Manle Lavender testified that petitioner

-6-

aided her in flJ-ling out

the absentee baIlot appllcation, Tr. 131, as well as the absentee

baLlot, Tr. 137-138.

Mr. Lewis l"linor showed very poor memory of the events underJ-ying his

absentee vote in the run-off, and testified that he could not identify

the absentee balLot appJ-lcatlon fiIled out ln hls name because: t'I cantt

read, you know. I dontt know one from the otherrrr Tr.:140. But it is

clear that he remembered petltloner providing hito rgith some

140-141,

PaPers so that he

could vote, without having

vote even though he could

to go to the pol-ls, Tf . L44. Ee could

not testlfy meanfully as to the mechanics of

the varlous papers with which heabsentee voting, or the slgnificance of

was provided.

Ms. Lucl11e Harrls testified that petitloner alded her in filling out

an absentee balLot appllcation prior to the run-off , Tr. l-L5. Ms. Ilarrls

absentee ballot voted in her name,testlfied that she had never seen the

Tr. 145. But Ms. Harrisr ba11ot appj-ication revealsthat the bal1ot was

sent to Ms. Ilarrlst home, Tr. L47-148. No connection was drawn by the

prosecution betweea petltloner, and the clain Ehat Ms. EarrLs never

recelved her absentee baLlot from the clerkrs office. Its. Harris did

testify that petitioners had discussed absentee voting with her,

and that Ms. Ilarris decided to vote for the candidates peEitloner

endorsed - t'the democratesr" Tr. 148. How Ms. Harris could claim

that she never recelved an abseatee bal-l-ot when one hras apparent,ly sent

to her home remalns unexplalned, but such discrepancy casts doubt only

on Ms. Harrlsr abllity to recollect and no! on petltionerts conduct.

To the extent Ms. Harris was able to testify about petitlonerrs conduct,

her testimony was consistent with the claim that petitloner was contentlous

in acting onJ.y with the knowledge and consent of the voter.

Ms. Mattle Gipsonts testimony drew no connection beEhreen petitioner

and Ms. Gipsonrs voting by absentee ballot. Ms. Gipson had no elear

memory of how she voted ln the run-off testifying on direct examtnatlon

that she voted in person, Tr. 100, and on cross-exErmination stating that she

had voted by absentee baLlot, Tr. L04.

Ms. Bessie Bll1ups testlfied that petitioner alded her in completlng

the absentee bal-lot appllcation, Tr. 152, and the absentee baIlot, Tr. L53-154,

158. There was contro\rersy over whether Ms. Billups or petitioner had

fl1led out the absentee ballot, Tr. L60-162, But thls sort of dispute is

irrelevant to the issue of petitionerts gullt. Wtrat is relevant is that

-8-

insofar as Ms. Bl11upts memory allowed her to testify as to the events

underlylng her absentee vote, she remembered petltioner's belp ln votiug

by absentee baLlot. Ms. Billupst lack oi clear memory (i.e., pertainlag

to who fiLled out her absentee balLot) cannot give rise to an inference

on fraud on the part of petltioner.

Ms. Fronnie Rice testified that peitioner came to vislt her before

the run-off, and aided her to apply for an absentee balLot. Tr. L6z.

Subsequently, IG. Rice testified, petitioner brought her an absentee balLot

which Ms. Rice voted, Tr. 168-169. The prosecutlousr att,empt to show that

Ms. Rlce did not si-gn the balLot, or dld not recelve the balLot in the -ail,

Tr- 165-L67, are irrelevant. It ls establlshed by Ms. Rlcers testimony that

petitioner was aiding I'ls. Rice to vote with Ms. Rlce's knowledge and coosent.

Ms. Clemmie Wells testified that she dld not know petit,ioner and had

no contact wj-th her regarding voting, Tr. L77. Ms. WeLls testlfled that she

remembred making an applleatlon for an absentee ballot in the run-off (fr. 171),

and could not remenber whether she ever saw or fllIed out an absentee ballot,

Tr. L76-L77.

Ms. Lula DeLoach recognized her writing on the absentee baLl-ot appJ.lca-

tion filed in her nam€r Tr. J.80, but did not reeognize the wrltings on the

appllcatlon as belng hers, Tr. 181. 0f coursq that the absentee ballot did not

contain l'Is. DeLoachrs handwritlng does not mean that she was defrauded,

and it certainly does not mean that petltioner defrauded her. Ms. Deloach

testified that

Deloach would

petltioner offered to fllL out a paper for her so that l'Is.

not have to go to the pol1s to vote in person, Tr. L83-184.

petLtioner fllIing outMs. Deloach testifled that she had no objection to

the papers "because I dldntt know what lt was all about. Id. Yet, plainJ-y,

as her testJ.mony reveals, Ms. Deloach did understand enough to know that

petltloner was

ln person. Id.

providing her with a way to vote without going to the poIIs

From the testlmotry of Ms. Deloach no inference of fraud on

the part of petitloner can reasonably be drawn.

Mr. Charl-es Cunningham remembered petitioner aiding hiro to flLl out

the appJ-j-cation for an absentee ba1Lot,

bal-lot voted ln hls name, Tr. 191-192.

Tr. l-89, as well- as the absentee

Ur. Cr:nningham testlfied that

petj.tioner read the names of the candidates oo the ball-ot to hfur and fl11ed

out the ballot for hln, Tr. L91. Yet, Mr. Cunningham recal-led believlng

that he was voting "for the Tom to be wetr" Tr, L89.

The attorney for both sides stlpulated as to the testimony of Ms.

-10-

Maudine Lathan. The stipulated testinony mrde no mention of petitioner

having had any connection with Ms. Lathamfs voLlng, Tr. 193

The voters who were ca11ed to testify agai.nst petltloner Lacked a

good memory, and an understanding of the voting process which would

enable them to testify intelJ-igently about the preclse events surroundlng

their vote. A ratlonal trier of fact cannot find guilt beyond a reasonabLe

doubt based on testimony as confllcting aod so lacking in clarity as to

the underlylng events.

Moreover, no matter how many lmperfectlons in procedure the prosecutlon

was able Lo uncover, and no matter hosre 111 equipped these voters nere --

by vLrtue of their very limited education and prevlous partlclpation l-n

politicaI affalrs -- to make meaningfuJ- choices as to the candidates, petitlooer

caurot be held crirninally liable unl-ess she purposefully and with evil intent,

deceived these voters. There is slnply no evidence of such deception. Nor is

lt reasonable to view the testimony of I,Is. Spann in isoLatlon -- it is

inconceivable that petitioners wouLd perpetrate fraud against Ms. Sparur

a1one.

-11-