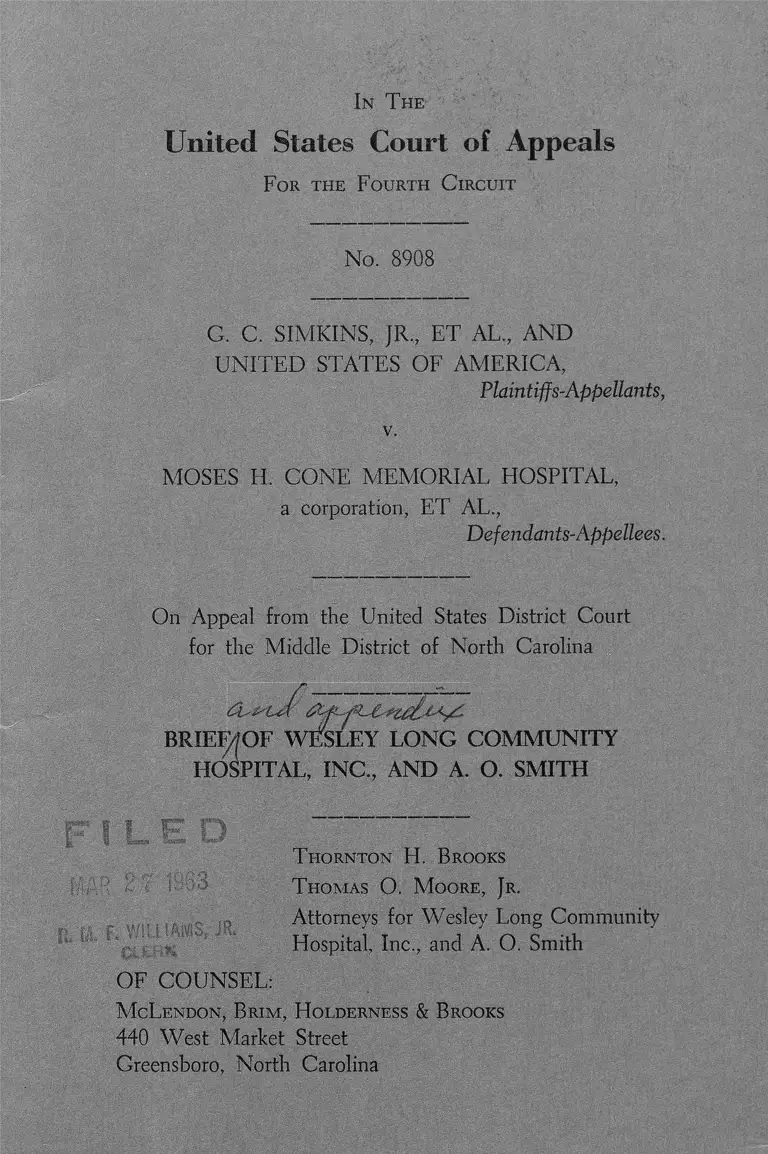

Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief and Appendix

Public Court Documents

March 27, 1963

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief and Appendix, 1963. 1c5b9f66-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e8a100e-5fc8-4568-bd8d-77c689fd3d6e/simkins-v-moses-h-cone-memorial-hospital-brief-and-appendix. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

In The

United States Court of Appeals

F o r t h e F o u r t h C i r c u it

MOSES H. CONE MEMORIAL HOSPITAL,

a corporation, ET AL.,

Defendants-A ppellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of North Carolina

BRIEF ( COMMUNITY

HOSPITAL, INC., AND A. O. SMITH

No. 8908

G. C. SIMKINS, JR., ET AL., AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

I pr

T h o r n t o n H. B r o o k s

T h o m a s O . M o o r e , Jr.

Attorneys for Wesley Long Community

Hospital, Inc., and A. O. Smith

OF COUNSEL:

M c L e n d o n , B r i m , H o l d e r n e s s & B r o o k s

440 West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carolina

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Argument __________________________________ 2

1. Background ________________________ 2

2. Eaton v. Walker Hospital is Controlling____ 2-10

3. Effect of receipt of federal financial

contributions under the Hill-Burton A ct_____10-17

4. Construction of hospitals not a state functional7-19

Conclusion _________________________________ 19-20

Appendix

Exhibit A _________________________________ A-l

Additional Excerpts from North Carolina

State Plan ___________________________A-2-4

Affidavit of A. O. Smith in Support of Response to

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment and

Preliminary Injunction___________________A-5

Hospital Survey and Construction B ill___ _____ A-7

Hospital Construction Act _________________ A-10

A Bill—S. 2625 ______________________ _____A-l 5

i

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Eaton v. Jam es Walker M emorial Hospital, 261 F.

2d 521; cert. den. 359 U. S. 984 ________________ 2

H enderson v. Trailway Bus C ompany, 194 F. Supp.

423 (1961) ______________________________ _...19

M cC abe v. A tchison, Topeka and S.F.R. Co.,

235 U. S. 151 (1914) ________________________16

GENERAL STATUTES

General Statutes §§ 131-126.1 through 131-126.17______ 3

ii

In The

United States Court of Appeals

F o r t h e F o u r t h C ir c u it

No. 8908

G. C. SIMKINS, JR., ET AL, AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

MOSES H. CONE MEMORIAL HOSPITAL,

a corporation, ET AL.,

D efendants-A ppellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of North Carolina

BRIEF OF WESLEY LONG COMMUNITY

HOSPITAL, INC., AND A. O. SMITH

2

A R G U M E N T

1. Background

The plaintiffs-appellants (herein referred to as Plaintiffs)

are Negro physicians-dentists-laymen who instituted a single

class action on 12 February 1962 in the District Court against

two different hospitals, The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hos

pital (herein referred to as Cone Hospital) and Wesley Long

Community Hospital, Inc. (herein referred to as Long Hos

pital) . Plaintiffs sought to enjoin the Hospitals from denying

them, admission to staff and treatment facilities on the basis

of race. The United States of America (herein referred to as

United States) was permitted to intervene,1 and has filed a

brief requesting that the judgment of the District Court be

reversed for similar reasons as argued by Plaintiffs.

Long Hospital’s factual situation is different from that of

Cone Hospital in two respects: selection of board of trustees

and training of nurses. It is believed, however, that the same

general principles of law are applicable and an effort will be

made to avoid duplication of argument.

2. Eaton v. Walker Hospital is controlling

Insofar as Long Hospital is concerned, the decision of this

Court in Eaton v. James Walker M emorial Hospital, 261 F.

V United States was allowed by the District Court “to intervene as a party to the

extent necessary for a proper presentation of the facts and law relating to the

constitutionality of the statute above referred to. W ith reference to motions

now pending before the court, the United States will be heard, within the

limitations just mentioned, on the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment’’

(PI. App. 188a). At the hearing of the case before the District Court on 26

lune 1962, in arguing the extent of intervention that should be permitted to

United States, the Attorney General stated: “MR. BARRETT: W ell, we

have been trying to be as candid as possible with respect to the question of

full participation. As I say, we do not propose to participate as a party with

respect to the question of the staff privileges aspect of the case, but beyond

that, under the intervention statute we believe that under the intervention

statute that we would have the same rights of participation as if we were a

party” (Tr. 108-9). United States devotes only seven pages of its brief

(pp. 40-48) to a discussion of its claim that Section 291e(f) of Title 42 is

violative of the Constitution. The remaining part of the United States’ brief

is devoted to a discussion of the merits of the case.

3

2d 521; cert, den. 359 U.S. 984, is controlling. The Eaton

case was decided in November 1958, with Judge Soper writ

ing the unanimous opinion for the Court, consisting of Judges

Sobeloff, Haynesworth and himself. The two cases are on

“all fours”:

a. The parties in both cases are of the same class. That

is, the plaintiffs are physicians licensed by the state of North

Carolina to practice their profession in this state; and the

defendants are bodies corporate under the laws of the state

of North Carolina vested with the authority to operate a non

profit hospital.

b. The jurisdiction asserted and the relief sought are the

same. In both cases jurisdiction was invoked under 28 U.S.C.

|| 1331 and 1343(3), and on the civil rights statute, 42 U.S.C.

111981 and 1983. The relief sought in both cases was an in

junction restraining the defendants from denying the plain

tiffs rights because of their race.

c. The same state licensing requirements were in force. In

both cases the hospitals were licensed by the state of North

Carolina pursuant to the provisions of General Statutes

5$ 131-126.1 through 131-126.17, and were subject to the

same rules and regulations of the North Carolina Medical

Care Commission.

d. In both cases the hospitals were exempt from ad va

lorem property taxes levied by the respective cities and coun

ties in which they were located.

e. Ownership of property. In Eaton, at the time of the

trial, title to the property was vested in the Board of Managers

of the hospital. In 1901 the city of Wilmington and the

county of New Hanover conveyed the hospital as it then

existed to the Board of Managers to hold in trust so long as it

should be maintained as such for the benefit of the city and

county. In case of disuse or abandonment, the property was

4

to revert to the city and county. Subsequently, additional land

was acquired by the Board of Managers in fee simple without

restrictions and additional buildings were erected thereon.

The title to all of Long Hospital’s property, both real and

personal, is vested in it in fee simple without restrictions, and

without any right of reversion to the city or county. The title

to its property was not derived from the city or county, but

rather was acquired from third parties with its own funds.

f. Trustees of hospitals. In Eaton, the original members

of the hospital’s Board of Managers were appointed pursuant

to a private act of the North Carolina Legislature. At the

time of trial, all members of the Board were elected by it and

it was a self-perpetuating board. The Board of Trustees of

Long Hospital are elected by it and it is a self-perpetuating

board. At no time has any member of the Long Hospital

Board of Trustees been elected or appointed thereto by any

public agency.

g. Financial contribution by city and county to hospital.

In Eaton, prior to 1951, the city and county made direct an

nual contributions for the support, maintenance and opera

tion of the hospital. These appropriations were derived from

taxes collected by the city and county. These funds were

used for the maintenance and operation, as well as construc

tion of the hospital. Subsequent to 1951, direct payments

were made by the city and county, pursuant to contract to

talling in excess of $250,000.00. At the time of the trial, the

city had no contract with the hospital and was not a source of

revenue. The county, however, at the time of the trial did pro

vide funds to the hospital according to contract for the care

of indigent patients at a negotiated per diem rate. The Pri

vate Laws of North Carolina of 1901, Chapter 12, provided

for annual appropriations to the hospital by the city and

county and required the Board of Managers to make annual

reports to the city and county concerning the conduct and

5

management of the hospital. There is no indication that this

statute was ever repealed. All private acts passed prior to 1953

were held to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of

North Carolina for other reasons.

Long Hospital has never received, directly or indirectly,

monetary contributions from either the city of Greensboro or

the county of Guilford.

h. Financial grants or contributions from Federal Gov

ernment. In Eaton, it was alleged that that hospital had from

time to time exercised the right of eminent domain, and had

“received large grants of money from the Federal Government

for expansion and maintenance of the said hospital.”2 Long

Hospital also “is the recipient of federal funds under the Hill-

Burton program in aid of its construction and expansion pro

gram” (Complaint, par. X, 13a) .

It is quite evident that the facts in the Long Hospital case

are much stronger for a holding of non-state action than was

present in the Eaton case. While, as shown, many of the facts

in the two cases are identical yet there are the following ele

ments of possible state action in the Eaton case that are not

present in the Long Hospital case:

1. In Eaton, the original hospital was established on a site

and the appropriation of certain monies for its maintenance

was made by the city and county under authority of an act of

the General Assembly of North Carolina. No analogous situ

ation exists with Long Hospital.

V At the hearing on, 26 June 1962 before the District Court on the instant

motions, counsel for Plaintiffs stated that “the funds were received in, the

Eaton case under some war-time emergency act” (Tr. 82). The act referred

to was the Defense Public Works Act (Act of October 14, 1940, as amended

June 28, 1941), 55 Stat. 361, 42 U.S.lC.A. 1531, et seq. The amount of the

grant from the Federal Government in Eaton was $508,000.00 and was used

to build a new wing on the hospital with an operating suite. Although this

amount and the use thereof is not shown in the record, as one of counsel

for the plaintiffs in the Eaton case is the same as counsel for Plaintiffs in the

present case, these facts can be verified.

6

2. The provisions of the deed by which the site of the hos

pital in Eaton was conveyed by the city and county to the

Board of Managers of that hospital constituted a conveyance

upon express trust to operate the hospital for the benefit of

the city and county, with reverter to the city and county in

case of disuse or abandonment. No such conveyance from

the city or county to Long Hospital is involved, and there is

no right of reverter to the city and county of its property in

the event of disuse or abandonment.

3. In Eaton, a self-perpetuating governing body was

placed in charge of the hospital by an act of the Legislature of

the state in compliance with the wishes of the donor of the

property. This situation is completely lacking at Long Hos

pital as it is a voluntarily formed corporation which provides

for its own Board of Trustees to operate the hospital.

This Court held in Eaton, and correctly we believe, that

the Walker Memorial Hospital “was not an instrumentality

of the State but a corporation managed and operated by an

independent board free from State control.” The facts of the

instant record clearly show that the same ruling of the Eaton

case should be applied to Long Hospital.

United States is strangely silent concerning the controlling

effect of Eaton on the Long Hospital. It refers to the Eaton

case at only one place in its Brief, page 5, and there it merely

recites the District Court’s reliance upon the case. It makes

no attempt to comment upon the ruling in Eaton nor does it

seek to distinguish it from the present case. Plaintiffs also fail

to come to real grips with the applicability of the Eaton case

to the Long Hospital factual situation. Plaintiffs half-heart

edly attempt to distinguish the two cases by a footnote treat

ment on page 25 of its Brief. Plaintiffs fail, however, to ade

quately distinguish the two cases. First, they say that “in

Eaton all governmental aid in the construction of facilities

ceased in 1901.” As shown, this is incorrect for the hospital in

7

Eaton “received large grants of money from the Federal Gov

ernment for expansion and maintenance of the said hospital'’

(paragraph 12 of Complaint in Eaton) . Next, the plaintiffs

say that the hospital in Eaton did not “have to conform to the

requirements and standards of the Hill-Burton Act”, but at

the hearing before the District Court the Plaintiffs and the

defendants “conceded that the Hill-Burton funds received by

the defendant hospitals should be considered as unrestricted

funds” (Opinion of District Court, 214-215a) .3 Thus, in de

termining whether state action results from an acceptance of

Hill-Burton funds, a recognition that such funds are to be

treated as though they are unrestricted, makes the two cases

parallel for, as was pointed out in Eaton (p. 525), the Su

preme Court has held “in a very similar situation . . . that a

grant of public land by an act of Congress to the Board of

Trustees of the University did not make the board a public

corporation.”

Plaintiffs then argue that Eaton does not control Long

Hospital because the resources which the hospital there re

ceived from the government for the treatment of indigent

patients amounted to only 4.5 per cent of the hospital’s total

3/ At the hearing before the District Court, Plaintiffs’ position with regard to the

nature of the federal contributions under the Hill-Burton Act is expressly

stated by counsel in answer to the Court’s inquiry, as follows:

“MR. MELTSNER: I am not sure precisely what you are getting at.

“THE COURT: W hat I am saying is this, that if Congress has enacted a

statute saying that we are going to make a billion dollars a year available to

private hospitals for construction on the basis of need, and we will survey, and

we will have the state to make the survey for us and wre are committed to the

proposition that we will give fifty percent of the construction cost to provide

hospital facilities for so many rooms for every 100,000 people throughout the

United States, and when that survey is made, in order to construct that

facility, we will give 50 percent of the cost, and nothing is said about how

you must operate it; we will just give you 50 percent of the cost. That is all

they say; no1 restrictions. Now would there be difference in that grant to

those hospitals under those situations than the grant they'' received here from

the government saying that you may use this money to build the facility

on a discriminatory basis; and they say, all right, under those circumstances,

we will accept those funds; is there any difference? Does one make the facility

more public, or the character of it more public than the other? I understand

that is the position that counsel for the Defendants take, and I want to know

your position.

“M R. MELTSNER: That is my position” (Tr. 80-81).

8

income. We know of no rule of law that applies the de

minimis doctrine to a determination of whether state action

is present. Even so, Plaintiffs have overlooked the fact that in

Eaton the original gift of the land and much of its early opera

tional grants came from the city and county, and that it also

“received large grants of money from the Federal Govern

ment for expansion and maintenance of the said hospital”

(Complaint). The fact that such funds had been received by

the hospital in previous years does not alter the legal conse

quences of the grant, and in any event the same situation

prevails with these hospitals.

Plaintiffs next urge as a reason why Eaton does not control

here is because “no governmental appointees sat on the Board

of the hospital in Eaton nor did it participate in any arrange

ment with state educational institutions.” But, as shown,

Plaintiffs make no claim that these situations exist at Long

Hospital.

Plaintiffs recognize that the hospital in Eaton was licensed

under the same North Carolina law applicable to Long Hos

pital, but seek to avoid this similarity by saying that the point

was not argued before this Court or discussed in its opinion.

Perhaps this point was not expressly argued before this Court

but it is recognized that the same licensing provisions and pro

cedures covered the hospitals in both cases and, as aptly ob

served by the District Court in its opinion (212a): “To

hold that all persons and businesses required to be licensed

by the state are; agents of the state would go completely be

yond anything that has ever been suggested by the courts.”

Finally, Plaintiffs argue that Eaton does not control Long

Hospital because at the former hospital “segregation was not

pursuant to authorization of federal law.” This attempted

distinction begs the question and lacks merit. Long and Cone

Hospitals have repeatedly stated that their segregation was not

made pursuant to any authorization contained in the Hill-

9

Burton Act. The District Court in its opinion (220a) ex

pressly notes that the defendants make no claim to “any right

or privilege under the separate but equal provisions of the

Hill-Burton Act.”

It is readily apparent that the only substantial distinctions

between Long Hospital and the hospital in Eaton lie in facts

that establish the latter’s governmental involvement to be

even more real than that of the former. Plaintiffs reject this

approach and apparently urge the Court to consider only the

“totality” of the contacts as though the whole were not equal

to the sum of its parts. This quaint arithmetical analogy,

taken out of context from Supreme Court dicta, provides a test

which is more easily espoused than applied. Plaintiffs seek

to persuade this Court to inject itself into the private affairs of

Long Hospital by adopting a strained, unreal and semantical

definition of state action that is unsupported by legal prece

dent. In effect, they feel that the law as established in the

Eaton case should be overruled by sociological and ethical

considerations which only tend to cloud and obscure the legal

question before the Court. In summary, or in “totality”, the

governmental contacts of the hospital in Eaton were as

follows:

(1) Tax exemption

(2) Licensed by state and subject to state regulation pur

suant to license

(3) Federal grants

(4) Service to the public

(5) History of county and city contributions

(6) Possibility of reverter to local government

(7) Evolution from governmental hospital to private

hospital

10

(8) Contractual agreement with county for care of in

digent patients

(9) Majority of Board of Managers originally appointed

by governmental agencies

In summary, or in “totality”, the governmental contacts of

Long Hospital are as follows:

(1) Tax exemption

(2) Licensed by state and subject to state regulation pur

suant to license

(3) Federal grants

(4) Service to the public

In Eaton, the above factors were alleged to be sufficient to

uphold the jurisdiction of the Court. The District Court dis

agreed and dismissed the complaint. This Court affirmed the

dismissal. It is submitted that if there was no jurisdiction

over the Walker Hospital, a! fortiori, there is no jurisdiction

over Long Hospital. 3

3. Effect of receipt of federal financial contributions under

the Hill-Burton Act.

The constitutional impact of governmental financial as

sistance to Long Hospital can be no greater than that of the

financial grants to the hospital in Eaton. The injunction

sought by Plaintiffs would impose Court controls over the

administration and operation of defendant hospitals on the

theory that in reality such operation is being performed by the

sovereign for the asserted reason that defendants are govern

mental agencies. The factor urged as the catalyst is the Hill-

Burton monies and the manner of their receipt. It is argued

that this transforms admittedly private operation and admin

istration into action somehow characterized as “public.” One

11

objection to this argument is that it overlooks the use to which

these governmental funds have been put. The governmental

funds received by the hospital in Eaton were spent for its ac

tual maintenance, operation and administration. This Court

properly held that governmental funds as an aid to operation

does not affect the private nature of the operation. Here it is

argued that governmental funds as an aid to construction and

expansion will render the subsequent administration of such

expanded facilities no longer private in nature. If the govern

ment, by its financial aid to the operation of the hospital in

Eaton did not thereby “insinuate” itself into its operation, it

follows that financial aid to the expansion of Long Hospital

did not “insinuate” the government into its operation.

United States goes even further by advancing an argument

for “State action” from a premise which has thus far been

denied legal precedent. This major premise is set forth in its

brief as follows (pp. 18-19) :

“Our position is based on the fact that the Hill-Burton

system contemplates a State obligation to plan for facilities

to provide adequate hospital service to all the people of

the State. To the extent that this obligation is carried out

by otherwise private institutions, th ese recip ien ts o f th e

fed era l grants are a ctin g fo r th e State and are th ere fo re

su b je ct , in this resp ect, to th e obliga tions im posed upon

State agen ts and instrum entalities b y th e F ourteen th

A mendm ent.” (Emphasis added)

-Stated differently, this argument seems to be that Congress

has decided that private entities are fulfilling a public need

and wishes to encourage them by financial grants in aid. How

ever. because the service they fulfill is of benefit to the public

in general, they are therefore acting for the state and on its

behalf Bv virtue of this service th ey b ecam e th e state, for

onlv the state must accord its citizens equal protection and

due process of law. Thus, there is no longer a sphere within

12

which private citizens can successfully provide basic public

necessities without in fact becoming the state. It is the nature

of the function performed rather than the degree of control

by public officials that determines when private action be

comes public. If we have correctly interpreted the argument

of United States, it is far reaching and without judicial

support.

United States requires something more than financial aid

in order to have “State action.” For this “something more”

it turns to the Hill-Burton Act and to fragments of its legisla

tive history without articulating whether the “something

more” would be sufficient absent the financial aid. It is sub

mitted that a proper analysis of the Hill-Burton Act reveals

this “something more” to be a fiction. In the words of the

District Court, “it can be fairly said, however, that the only

significance of these requirements (minimum construction

and equipment standards) is to insure properly planned and

well constructed facilities that can be efficiently operated.”

The Act gives rise to no governmental controls over the Hos

pitals’ operation and administration. Moreover, it is ques

tionable whether restrictions of future operations as a condi

tion of the grant would render Long Hospital a government

instrumentality in view of the Congressional obligation to in

sure that the public funds would not be wasted by the recipi

ent. In short, this “something more” is lacking just as Con

gress intended it to be, This intent is clearly stated in the fol

lowing passage in the Act itself:

“Except as otherwise specifically provided, nothing in

this sub-chapter shall be construed as conferring on any

Federal officer or employee the right to exercise any super

vision or control over the administration, personnel, main

tenance, or operation of any hospital, . . . with respect to

which any funds have been or may be expended under

this sub-chapter.” (42 U.S.C. § 291m)

13

Plaintiffs place great stress upon those provisions of the

Hill-Burton Act which provide that the States desiring to re

ceive funds must submit a state plan for approval by the Sur

geon General. This is in fulfillment of the first major pur

pose of the Act as stated in Section 291, i.e., to assist the states

to inventory their existing hospitals and develop programs for

construction of public and o th er n onp ro fit hospitals. The

states desiring to receive federal grants to help finance their

survey must submit a plan which conforms to the require

ments of Section 291 f. Once this has been done, the first

major congressional intent has been fulfilled — the only one

contemplating or involving state action.

The second major purpose of Hill-Burton is stated in

Section 291 to be to assist in the construction of public and

o th er n onp ro fit hospitals. It is here that governmental in

volvement beyond financial assistance ceases. It ceases be

cause Congress intended it to cease at that point. This is

clearly established in the provisions of Section 291 m quoted

above. The effect of Hill-Burton is much more simple and

straightforward than Plaintiffs and United States would lead

the Court to believe. Congress decided that it would be a

good thing to spend federal funds in aid of private hospital

construction. United States concedes that this without

“something more” is insufficient to transform otherwise pri

vate action into state action. They hope to establish this

something more by pointing to the state plan which must be

approved by the Surgeon General. But there is no magic in

Section 291 f. This section simply sets forth the requirements

for the state plan. Congress merely decided to abdicate to the

states the congressional responsibility of insuring that the fed

eral monies will be disbursed in the most efficient manner pos

sible to ultimate recipients who meet the necessary require

ments and according to priorities established by the states.

Presumably every federal grant to a private institution

14

should be to fulfill an important need. It is also basic that

Congress must establish guidelines as to basic qualifications

of prospective recipients of the grant. Furthermore, it often

happens that the number of qualified recipients will exceed

the amount of funds available so a system of priorities must be

established. Likewise, Congress must be satisfied that the

funds will be used to further the basic purposes of the grant

itself. It would be of no avail to grant funds to a private

school for the construction of a new library if the school is

free to use the money to build a football stadium, or a library

that will collapse in two years, or a library without book

shelves. Finally, it is necessary to gather together a group of

citizens to administer the distribution of the funds so that the

foregoing restrictions will be followed. In this sense, there is

no such thing as an unrestricted grant. It is submitted that

Hill-Burton goes no further than what is in keeping with

sound fiscal policy. The United States’ brief (pp. 28-29, p.

29, fn 20) recognizes that the Act and its legislative history is

replete with provisions and language indicating that the Hill-

Burton Act constitutes merely a program of federal grants-in-

aid. It is submitted that the simple answer to the simple ques

tion posed by the case at bar can be found in these provisions.

Plaintiffs seek to persuade this Court that the provisions

of Section 29le (f) somehow change the private nature of the

Hospital corporations. The discussion is understandably

vague and precedents cited deal mostly with situations of state

enforcement of criminal statutes. Perhaps a close reading of

the discrimination provisions in the Act may serve to clear

the air. First, it must be clearly kept in mind that the Act

requires n o th in g of the hospitals in the way of discrimina

tion or non-discrimination. United States apparently concedes

that Congress is under no obligation to do so (Brief, p. 39) .

The Surgeon General is given an option to require nondis

crimination as a condition of the grant. The record shows that

15

such option was not exercised in the instant case. A reason for

the non-requirement of nondiscrimination is that separate hos

pital facilities are available for separate population groups in

the Greensboro area. In such a case Congress precluded the

Surgeon General from requiring a nondiscrimination pledge

from a prospective recipient. Presumably the Surgeon General

would have no authority to require nondiscrimination unless

he were specifically authorized to do so by Congress. Con

gress has authorized him to do so if he wishes but only if

certain conditions do not exist. Similarly, Congress author

ized him to require a prospective recipient to treat indigent

patients but limited this authority to those situations where

it would be financially feasible for the recipient to do so. This

is an entirely different situation from one in which a recipient

was required to discriminate in order to be eligible for funds.

To say that Congress sanctioned discrimination would lead to

the conclusion that it would have impliedly sanctioned dis

crimination by private hospitals had it remained altogether

silent on the subject.

Hill-Burton Act is not governmental sanction of discrimi

nation. Plaintiffs argue that “discrimination was affirmatively

sanctioned by a federal statute and federal regulations, and by

a State Plan for hospital construction on a segregated basis”

(Brief, p. 31). United States frames the same argument in a

slightly different manner: “The essential point is that, even

in the case of otherwise private hospitals, Congress was un

willing to leave the avoidance of unconstitutional discrimina

tion to free private decision. Congress perceived and forced

the States (and also the hospitals choosing to participate in

the program) to accept a governmental obligation. . . . Any

one taking the money would take it, as it were, subject to the

trust, and in performing the trust the taker would be acting

for the government and subject, in this respect, to its consti

tutional obligations” (Brief, pp. 33-34). In support of this

16

argument Plaintiffs and United States both place reliance

upon the case of M cC abe v. A tchison, Topeka and S.F.R.

Co., 235 U.S. 151 (1914). Reliance upon this decision is

not well founded. There the Supreme Court held that the

allegations of the complaint of the Negro plaintiffs were too

vague to justify the granting of an injunction. In this respect,

the decision below was affirmed. However, as additional

grounds for denying relief, the Circuit Court of Appeals had

held that the Oklahoma statute authorizing absolute discrimi

nation on railroad luxury facilities was not in conflict with

the Fourteenth Amendment as it was competent for the state

legislature to consider the limited demand by the Negro race

for such accommodations. The Supreme Court disagreed

with this without considering or discussing the proper way in

which the constitutionality of such a statute could be called

into question. The Court did not indicate that an injunction

would have been allowed if plaintiffs could have shown irre

parable injury. Mr. Justice Plughes theorized that if a private

corporation w hile a ctin g under authority o f state law, deprives

an individual of his Fourteenth Amendment rights such indi

vidual may properly complain that his privilege has been in

vaded. While it is difficult to speculate as to whether the

Court felt that the defendants in question were acting under

authority of state law in that case since the point was not

raised, it should be noted, however, that by virtue of the

wording of the statute in question it was necessary for the

carrier to rely on the statutory exception in order to be re

moved from the broad mandatory provisions of the statute.

In contrast, the Hill-Burton Act does not impose any

obligation upon the hospitals to desegregate or to maintain

segregated facilities. A conclusive answer to the argument of

Plaintiffs and United States is the fact that one of the defend

ants herein, Cone Hospital, maintains a non-segregated hos

pital to a limited degree (see Plaintiffs’ Brief, p. 5, fn 4, as to

17

admission of Negro patients, and p. 6 as to its admission of

Negro physicians-dentists to staff privileges). The finding of

the District Court on this point needs to be repeated (214a) :

“Racial discrimination, it should be emphasized, is per

mitted, not required. As evidence of the fact that the de

fendants do not consider themselves obligated under the

agreement permitting segregation, the Cone Hospital has

for some time admitted Negro patients on a limited basis.

Additionally, the defendants have repeatedly stated, both

in their briefs and oral arguments, that they in no way rely

upon the provisions of the Hill-Burton Act, or their agree

ment with the North Carolina Medical Care Commission,

which permit discrimination. . . . ”

United States says in its brief (p. 33): “Whether in the ab

sence of this governmental supervision and control racially

restrictive admission policies of Hill-Burton hospitals would

otherwise be purely 'private action’ and subject to no consti

tutional strictures need not be considered.” United States

thereby begs the very question here presented, because in fact

we do have an “absence of this governmental supervision.”

4. Construction of hospitals not a state function.

United States at pages 18-22 of its brief advances the

argument that the Hill-Burton system contemplates a State

obligation to plan for facilities to provide for hospital service

to all the people, and that when a private institution becomes

the recipient of federal grants it “becomes pro tanto a state in

strumentality with concomitant obligations” (p. 20). This

theory is recurrent in various forms throughout the briefs of

both Plaintiffs and United States. Thus, United States argues

that if private facilities appear inadequate in a particular area

the State would have to fill in with governmental institutions

(p. 20); and that the State has assumed as a State function

the obligation of planning for adequate hospital care (pp.

18

22-23.) United States urges that Congress regarded the

availability of hospital services to be a State responsibility, and

argues that these defendant hospitals fulfill a public function

which the State would have to perform if the hospitals did not.

This simply is not the case. Congress did not intend that

the Federal or State government enter the business of provid

ing hospital services. This was specifically left to the individ

ual recipients of the funds on a voluntary basis. If a group of

citizens in an area in which hospital facilities are inadequate

do not desire to construct a hospital or expand the facilities

then existing, no pressures are exerted by the State to con

struct same nor will it step in and provide the facilities itself.

The obligation to provide the facilities remains with the citi

zens. The funds are made available only on a “matching

basis”; that is, the private institution or public hospital must

put up its own funds to match those received under Hill-

Burton. The obligation of the State is only to plan in the

generally accepted sense of that word, and to insure a system

of priorities for distribution of the Federal funds to areas

where there is the greater need. At the time of the passage of

the Act, there were many areas of North Carolina in which no

hospital facilities whatsoever were available and indeed this

situation presently exists. The Government thus has not effec

tively “planned” facilities for these areas, in the sense that it

has gone into the business of affirmatively providing facilities

there. This is not a State obligation, and Congress did not

intend it to be. In fact, Congress took pains to insure that

the Act would not produce such a result. The States do survey

and submit “plans”, but this is for the sole purpose of insur

ing equitable distribution and proper administration of the

Federal funds.

Furthermore, even if Long Hospital were providing a serv

ice which is of a type that the State had also assumed an obli

gation to provide, there is no legal precedent for the proposi

19

tion that this is State action within the meaning of the con

stitution. Plaintiffs and United States in this regard have tried

to equate hospital care with public education which is a State

obligation to furnish. As demonstrated above, this is not the

case with medical facilities. Assuming, however, that furnish

ing hospital care could be fairly classified as a State obligation,

Long Hospital is still no more subject to constitutional restric

tions than a good faith private college which receives Federal

funds for construction of a research center or a new wing to

its library. Here again Plaintiffs and United States miscon

ceive the basic functioning of our Federal form of Govern

ment. When private citizens render service to the public, they

do not thereby become the sovereign, even in those areas

where the State has also chosen to act. And merely because

the State helps in the administration and disbursement of

federal funds to the end that more people may have medical

facilities available, it does not thereby make the construction

and expansion of the facilities a State obligation.

CONCLUSION

The principle of law applicable to a determination of this

case was succinctly stated by Judge Bryan to be: “Racial seg

regation on property in private demesne has never in law been

condemnable. Indeed, the occupant may lawfully forbid any

and all persons, regardless of his reason or their race or reli

gion, to enter or remain upon any part of his premises which

are not devoted to a public use.”4/

This Court has previously applied such principle of law to

facts parallel with those of Long Hospital in Eaton, and there

affirmed the dismissal of the complaint by the District Court.

As stated by Judge Soper in Eaton, the Court may not

take into account “the ethical quality of the action’7 of the

hospitals. As Long Hospital is a private corporation whose

i/ H enderson v. Trailway Bus Company, 194 F. Supp. 423 (1961). Three-judge

court composed of Judges Boreman, Bryan, and Lewis, American Civil Lib

erties Union appeared as amicus curiae.

20

premises are not devoted to a public use and as it is not an

instrumentality of the State, neither a sociological-economic-

political argument nor a strained construction of Congres

sional purpose will save this complaint from dismissal in a fed

eral court. If the doors of Long Hospital are to be involun

tarily opened to the public prospectively, the keys are in the

possession of the legislature,5/ or of the executive,6/ but are

not to be found retroactively in the judiciary.7/

The Hill-Burton Act was enacted into law in 1946, and

since that date the disbursement of millions of dollars have

been approved by the Surgeon General under State plans for

territorial areas where separate hospital facilities were pro

vided for separate population groups. Congress has not

amended the law since its enactment. United States has not

heretofore concerned itself with the administration of the

Act. This action and intervention sixteen years after the en

actment of the Act comes late in the day in an effort to find

a congressional intent that never existed.

The judgment of the District Court was correct and

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

T h o r n t o n H . B r o o k s

T h o m a s O. M o o r e , J r .

A ttorneys fo r W esley L ong C om m unity

Hospital, In c, and A. O. Smith

OF COUNSEL:

M c L e n d o n , B r i m , H o l d e r n e s s & B r o o k s

440 West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carolina

5/ See S.2625, a bill to' amend the Act to prohibit discrimination in any respect

on account of race, creed, or color in hospital facilities, Appendix p. A-l S, post.

6/ Cf. Executive Order 11063, issued 20 November 1962, providing that racial

and religious discrimination in the sale or rental of federally owned, operated

or finan ced housing is forbidden for the future. The Order provides that as to

past housing with federal financial assistance the appropriate federal agencies

will seek to promote the voluntary abandonment of discrimination.

V Eaton v. James Walker M emorial Hospital, supra.

Appendix

Exhibit A—Attached to Part I of Project Construction Appli

cation of Long Hospital—Item D (See Plaintiffs’ Appendix

93a).

EXHIBIT “A”

Supplement to Section 5D, Part 1, Project Construction Ap-

cation for Project No. NC-311, Wesley Long Community

Hospital, Greensboro, North Carolina, completed according

to Instructions for Filling Out the Project Construction Appli

cation, Form PHS-62(HF).

1. Nature of Construction:

The proposed 150 bed Wesley Long Community LIos-

pital will replace the existing 78 bed Wesley Long Com

munity Hospital at Greensboro, North Carolina. At

the completion of the proposed new project, the Board

of Trustees of Wesley Long Community Hospital have

agreed, by resolution, to abandon the existing 78 bed

facility for hospital use. l ir e new hospital will be con

structed of modern, lire resistant and functional

materials.

2. Need for Project:

The Guilford County area has a civilian population of

approximately 144,859. Based on the area ratio there is

a need of 652 beds. Seven hundred fifty-four (754) have

been planned for the area and at present time 451 suit

able beds exist. There remains an additional need of

303 hospital beds. Only 59.8% of needs have been met.

3. Nature of the Program for Project:

The proposed hospital will offer services of a general

hospital — medical, surgical, obstetrical and pediatrics.

A-2

Beds will be assigned approximately:

Medical — 35%

Surgical — 30%

Obstetrical — 2 5 %

Pediatrics — 10%

There is a medical staff of sufficient number to staff the

hospital. A nursing staff, technicians and other person

nel are and will continue to be available.

4. General Remarks:

No other factors.

ADDITIONAL EXCERPTS FROM

NORTH CAROLINA STATE PLAN

GENERAL HOSPITALS

For purposes of planning, the Commission has tradition

ally designated the county as the hospital service area. In sev

eral instances to allow for local considerations, one or more

counties have been combined in one service area. Several

counties have, for the same reason, been subdivided into the

service areas. While the county is accepted as the service

area, the Commission exercises discretion with regard to ap

proving applications for hospital projects where, in view of

county population and other local factors, a hospital is not

considered to be needed or the ability of the area to staff and

support a hospital adequately is questionable. Accordingly,

the Commission is under no obligation to approve a hospital

for a county merely on the basis there are no existing facilities

within the area.

Occupancy data for the individual hospitals have been ob

tained from reports recently submitted for licensing purposes.

Substantial variations in the bed count from previous revi

sions have been explained by footnote on Form PHS-5.

A-3

Initially approved projects for which Part 1 of the Project

Construction Application has been, or is in the process of

being, submitted for general hospital construction have been

included in the Plan as existing facilities. Also, construction

of additional general hospital facilities without federal aid

have been shown as existing facilities provided that contracts

have been awarded.

Following are the procedures used for assigning beds to

General Hospital areas to arrive at relative need:

Areas are classified (a) Base—An area having at least

one general hospital with a bed capacity of 200 or more

beds and having a comprehensive representation of the

various specialties of medicine, (b) Intermediate—An area

having or that will have at least one general hospital with

a bed capacity of at least 100 beds, (c) Plural—Any area

not designated as Base or Intermediate.

In lieu of the method previously used for assigning

general hospital beds, the Commission, for the purposes of

this revision of the Plan, has assigned each hospital area

the minimum of 2.5 beds per thousand and in cases where

utilization and the factors specified below merit beds in

excess of 2.5 per thousand, the beds planned for such areas

have been adjusted.

There is no justification for the arbitrary assignment of

beds on the basis of 4.5 per thousand for Base areas, 4 per

thousand for Intermediate areas and 2.5 for Rural areas.

This in the past has resulted in ridiculous incidents. In

realization of the fact that local conditions will influence

bed need and that beds are generally assigned in accord

ance with the above rather arbitrary consideration, the fol

lowing method provides more uniformity in distribution

in accordance with anticipated need for the following year.

The factors listed below have been utilized in exceptional

A-4

areas where the 2.5 beds per thousand ratio does not satisfy

immediate or long range needs:

A. M etropolitan Areas having dense population concen

tration, high utilization of existing facilities and with

a comprehensive representation of medical specialties.

B. H ighly Industrialized Areas with a relatively dense

population.

C. D efen se Areas in which additional beds should be

planned to care for dependents of Service Personnel

and an influx of Civilian Personnel.

D. R esort Areas in which additional beds should be

planned to allow for peak seasonal loads.

E. D em onstrated N eed in an area (1) for hospitals of

50 beds or less with occupancy of 60% or more and

(2) for hospitals with beds in excess of 50 with occu

pancy of 75% or more.

F. Existing Facilities — All areas are given credit for exist

ing facilities regardless of utilization.

G. Areas w ith T ea ch in g Hospitals A ssociated w ith

S chools o f M ed icin e (M edica l C enters) — See expla

nation under “Special Areas.”

These areas have been indicated on Form “Medical Facili

ties Summary” under the Area Column.

# £ # # #

For planning purposes, all facilities of 15 beds and less are

classified as replaceable in view of the fact that it can be

assumed that hospitals of such limited size cannot offer the

broad services expected of the general hospital. Facilities of

this category, therefore, are omitted from the State Plan.

A-5

AFFIDAVIT OF A. O. SMITH IN SUPPORT OF RE

SPONSE TO PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

(FILED: 8 JUNE 1962)

A F F I D A V I T

A. O. SMITH, first being duly sworn, deposes and says:

I.

That he resides in Greensboro, North Carolina, and has

served as Administrator of Wesley Long Community Hos

pital, Inc., for twenty-three years. That he is familiar with the

hospital and medical facilities in the county in which this hos

pital is located, namely, Guilford County, North Carolina.

II.

That L. Richardson Memorial Hospital, a hospital serving

Negroes in the community of Greensboro and an applicant

for Hilll-Burton funds for its construction and expansion pro

gram, has on hand and in operation a diagnostic X-ray ma

chine and complete available facilities to provide periodic

clinical evaluation of a person who has a confirmed gastric

ulcer of thirty-five years duration. That the said L. Richard

son Memorial Plospital has employed on its staff a qualified

and competent radiologist to operate the diagnostic X-ray

machine and facilities available at such hospital, and there

are other members of the staff of that hospital who can make

periodic clinical evaluations of a person suffering from a con

firmed gastric ulcer, including the making of necessary labora

tory procedures and tests. That the medical equipment and

facilities for the treatment of a confirmed gastric ulcer at

Wesley Long Community Hospital, Inc., are believed to be

no more complete nor better than those available at the L.

Richardson Memorial Hospital, or hospitals in High Point, or

at the offices of orivate physicians.

A-6

III.

That Wesley Long Community Hospital, Inc., has no

special dental facilities applicable to the removal of impacted

teeth. That although it has a dental chair as is commonly

found in a dentist’s office, and an oral rinse basin attached

thereto such as found in any dentist’s office, yet these facili

ties are not used in the removal of impacted teeth. When

patients are brought to Wesley Long Community Hospital,

Inc., for the removal of impacted teeth they are operated upon

on general operating tables such as used for general opera

tions. The dental surgeons who perform operations at Wes

ley Long bring their own instruments and equipment and the

hospital does not maintain any special dental equipment for

their use. The dental facilities available at L. Richardson Me

morial Hospital for the removal of an impacted molar tooth

are equal to those at Wesley Long, and impacted molars are

removed at that hospital by dental surgeons in the regular

course.

This the 7th day of June, 1962.

/s/ A. O. SMITH

Affiant

SWORN to and subscribed before

me this the 7th day of June, 1962.

/s/ JOYCE F. TROGDON

Notary Public

My Commission Expires: June 5, 1963.

CALENDAR NO. 678

79TH CONGRESS :

1st SESSION :

S E N A T E

: REPORT

: NO. 674

A-7

HOSPITAL SURVEY AND CONSTRUCTION BILL

OCTOBER 30, 1945. — Ordered to be printed

MR. HILL, from the Committee on Education and Labor,

submitted the following

R E P O R T

[To accompany S. 191]

The Committee on Education and Labor to whom was

referred the bill (S. 191) to amend the Public Health Service

Act to authorize grants to the States for surveying their hos

pitals and public health centers and for planning construction

of additional facilities, and to authorize grants to assist in

such construction, having considered the same, report favor

ably thereon with an amendment in the nature of a substitute

and recommend that the bill as amended do pass.

# # # #

II. SUMMARY OF BASIC PROVISIONS OF BILL

In brief summary, S. 191 proposes a program of Federal

grants-in-aid for two purposes:

1. To assist the States to ascertain their hospital and

public-health-facility needs through State-wide surveys and

to develop state-wide programs for construction of those

facilities needed to supplement existing facilities so as to

serve all the people of the State, and

2. To aid in the construction of those necessary facili

ties for public and voluntary nonprofit hospitals and for

public health centers, which State and local resources can

help build and can maintain, and which are in conformity

with the approved State construction program and the

standards for construction projects required under the bill.

An aDpropriation of $5,000,000 is authorized for the survey

A-8

and planning features of the bill, and $75,000,000 for each

of the five fiscal years 1947 to 1951 for the construction

program.

IV. SPECIAL PROBLEMS CONSIDERED BY

COMMITTEE

* * * *

A related problem intensively studied by the committee

was the assurance of the maintenance and operation of the

facilities which would be built under this program. Because

of the provision in this bill requiring any applicant for con

struction assistance to assure that financial support will be

available for maintenance and operation of the facility when

built, there is the danger that the communities having the

greatest need for such facilities may be unable to secure them

unless the State comes to their aid. In recommending this

bill, the committee recognizes that S. 191 is addressed only

to the provision of physical plant, and that it does not directly

deal with the maintenance and operation problem, which is a

serious one. It is the conclusion of the committee that assist

ance in the cost of maintenance and operation of hospitals in

the neediest areas should be considered in separate legislation,

when more information is available from the surveys to be

made.

* * * #

V. ANALYSIS OF BILL

PART A. PURPOSES

# # # #

The bill is not a Federal hospital construction bill. The

need for a country-wide program of hospital construction has

been demonstrated. It remained for the committee to con

sider and determine the relationship that should exist between

the Federal Government and the States in planning and carry

ing out such a program. The committee believes that a Fed-

A-9

eral-aid program of the character set forth in the reported bill,

which will supplement State and. loca l funds for planning and

carrying out a construction program, but will at the same time

encourage the States to assume the responsibility for carrying

out the program to the greatest possible extent consistent with

a proper check upon expenditure of Federal appropriations,

will be most effective in a long-range hospital-construction

program.

# # # #

PART C. CONSTRUCTION

❖ # # #

G eneral regu lations. . . . The committee recognizes the

impracticability, as a general rule, of attempting to write de

tailed administrative regulations into a statute. At the same

time, having in mind the underlying purpose of preserving so

far as practicable the independence of the States in carrying

out their plans, the committee felt that the Congress should

specify general requirements and limit the Federal Govern

ment’s regulatory control to those requirements. The matters

in question were given most careful consideration and it is

believed the scope of the Federal regulatory powers is con

sistent with effective Federal control of appropriated moneys.

# * * *

PART D. MISCELLANEOUS

* # # #

The concluding section, added by the committee amend

ment, would make clear that except in the matters specifically

dealt with elsewhere in the title, the title does not confer on

any Federal officer or employee any supervisory authority over

the administration, personnel, maintenance, or operation of

any hospital receiving Federal aid under the title.

A-10

HOSPITAL CONSTRUCTION ACT

H E A R I N G S

BEFORE THE

COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR

U N I T E D S T A T E S S E N A T E

SEVENTY-NINTH CONGRESS

FIRST SESSION

ON

S. 191

A BILL TO AMEND THE PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE

ACT TO AUTHORIZE GRANTS TO THE STATES

FOR SURVEYING THEIR HOSPITALS AND PUBLIC

HEALTH CENTERS AND FOR PLANNING CON

STRUCTION OF ADDITIONAL FACILITIES, AND

TO AUTHORIZE GRANTS TO ASSIST IN SUCH

CONSTRUCTION.

FEBRUARY 26, 27, 28, MARCH 12, 13, AND 14, 1945

S. 191 was introduced into the Senate by Senator Lister

Hill of Alabama and Senator Harold Burton of Ohio. At the

Hearings before the Senate Committee on Education and

Labor on February 26, 1945, Senator Hill made a statement

with reference to the Bill. Among his statements are the fol

lowing:

He pointed out that several possible methods of approach

had been explored by the Subcommittee and that it was

agreed that certain broad general principles be made a part of

any federal-aid legislation. One of these principles was that

“voluntary nonprofit hospitals as well as State, county, and

municipal hospitals shall be eligible for assistance” (page 8).

“Accordingly, after due and careful consideration of all the

A-ll

factors mentioned before, Senator Burton and I introduced

into the Senate as an amendment to the public health service

law of 1944 a bill known as Senate bill 191, ‘The Hospital

Construction Act.’ ” (Page 8).

Statement of Dr. Donald C. Smeltzer, President, Ameri

can Hospital Association, page 14:

“This committee is undoubtedly familiar with the

background of the. nonprofit community hospital. Organ

ized by the citizens of the community, these hospitals now

render a major portion of the general hospital care to the

citizens of this country. Many of these voluntary hospitals

are operated by the various churches. Their organization

and support results from the finest attitudes in our society.

Private charity through these organizations endeavors to

assist in the healing of all members of society. This bill

provides that Federal funds may be granted to nonprofit

hospitals and to hospitals owned and operated by subdivi

sions of Government. The voluntary hospitals of this

country have played a dominant role in developing im

provements in hospital methods and in raising the quality

of hospital care for the people of this country. Public hos

pitals are needed, particularly for the care of mental pa

tients and the tuberculous. However, it is fortunate that

in legislation with the broad aims indicated in this bill,

provision is made for maintaining the best in our present

system of hospital service by making possible grants to

both nonprofit and governmental hospitals/'

February 27, 1945, Statement of Dr. Thomas Parran, Sur

geon General, United States Public Health Service:

“DR. PARRAN. From the above concept, it should

be clear that I am not recommending a system of federally

operated hospitals. On the contrary, what I am suggesting

and what Senate bill 191 would provide is that the Federal

A-12

Government help the States to fill out the missing pieces

in the present hospital pattern and that the hos

pitals continue to be under local government and volun

tary management as they are now. Quite naturally, a com

pletely integrated hospital system such as I have described

is an objective to be accomplished by education, mutual

agreement, voluntary effort and such encouragement as

government may be able to offer.” (Page 60)

❖ # #

"DR. PARRAN. As to one aspect of your question, or

statement, Senator Taft, including the question which I

think you raised yesterday specifically, that is, would it be

more desirable to authorize loans instead of grants, or

loans as well as grants, for the construction of hospitals

and other health facilities, I think that is a point which

this committee might wish to consider.” (Page 77)

* * *

Statement of William B. Umstead, Durham, North Caro

lina, former Congressman. Appearing as personal representa

tive of the Governor of North Carolina:

"In February 1944 the Governor of our State, appoint

ed a commission of 50 representative North Carolinians,

including leading physicians and laymen, to make a survey

of our hospital and medical needs and to recommend a

program to the people and the General Assembly of North

Carolina. Among other things, this commission found

that 41 States of the Union now rank ahead of North

Carolina in the number of hospital beds per thousand

population; 44 States rank ahead of North Carolina in

the number of physicians per thousand population; 40

States have a smaller percentage of mothers dying in child

birth; 38 States have a small percentage of infant deaths,

and in 1944, 47 States had a smaller percentage of selec

A-13

tive-service rejections for physical defects. North Carolina,

with a population of approximately three and one-half

millions, has only 1 city with over 100,000 inhabitants.

Most of our people live in rural areas and small towns. The

commission found: There are 2.37 hospital beds per thou

sand population; there are 34 counties without hospitals;

for our Negro population, which is approximately 1,000,-

000, there are 1.66 hospital beds per thousand; we have 1

physician per 1,938 population.

“Many other interesting and impressive facts were dis

closed by the commission. These are sufficient, however,

to clearly demonstrate the need for additional doctors and

hospital facilities in North Carolina.” (Page 283)

“The proposed plan lays a solid foundation for State

cooperation with the Federal Government, as required by

Senate bill 191, and designates the North Carolina Medi

cal Care Commission as the agency of the State for the

administration of the plan as proposed in the senate bill

referred to. It also provides for the creation of an advisory

council, as required by the Hill-Burton bill.” (Page 284)

* # #

“SENATOR SMITPI. Mr. Umstead, you confirm

Dr. Reynolds’ statement that probably, if this plan goes

through, North Carolina can take care of the maintenance

problem. I notice in your bill you provide maintenance

for the indigent people who cannot provide for their own

care.

“MR. UMSTEAD. Yes, Senator. It is not contem

plated, however, under the proposed plan in our State, to

which I referred, that the State government will have any

thing to do, as such, with the local operation of the hos

A-14

pital unit or public-health center, except insofar as it

would be necessary for that hospital unit to meet the re

quirements of the commission before it could participate

in the plan and receive payment for indigent patients.

“SENATOR SMITH. You plan to decentralize right

down to the local unit?

“MR. UMSTEAD. Yes, sir. The financial condition

of the area or the county, the means at their command,

their own efforts, the needs of the hospital, and various

other things, would enter into the decision of our commis

sion, as I understand it, in dealing with the necessity of a

hospital at that particular place. When the necessity has

been established in accordance with the qualifications laid

down by the commission — and, of course, I do not know

what they will be, except as to certain restrictions and re

quirements set forth in the bill — have been complied with

and the construction completed and the hospital

equipped, I know of nothing in the proposed State legis

lation which would give to the commission the control of

the operation of that hospital unit.

“If I may go one step further, I think it would be, at

least it is my opinion that it would be, exceedingly difficult

and very unwise for either the State or the Federal Gov

ernment to undertake to go so far as to assume the main

tenance and the operating responsibility for the local hos

pital unit. [Page 284]

* $ *

‘SENATOR DONNELL. Would you favor the ac

ceptance by your State of Federal funds for the operation

of a hospital if that acceptance involved giving to the

Federal Government the right to determine the number

of doctors, the number of nurses, the medical treatment,

and the type of equipment in the local hospital?

A-15

“MR. UMSTEAD. You mean if it gave to the Fed

eral Government the right to control, direct, and supervise

the operation of the hospital unit?

“SENATOR DONNELL. Or to veto the views of the

local authorities.

“MR. UMSTEAD. Speaking for myself, Senator, I

would not be in favor of that.

“SENATOR DONNELL. Yes, sir.” (Page 285)

87th CONGRESS

1st Session

S. 2625

IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES

September 23, 1961

M r . Javits introduced the following bill; which was read

twice and referred to the Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare

A BILL

To amend the Hospital Survey and Construction Act to pro

hibit discrimination in any respect whatsoever on account

of race, creed, or color in hospital facilities.

Be it en a cted by th e Senate and H ouse o f R epresen ta tives

o f th e U nited States o f America in C ongress assem bled , That

subsection (f) of section 622 of the Hospital Survey and Con

struction Act, as amended, is further amended to read as

follows:

A-16

“That the State plan shall provide for adequate hospital

facilities for the people residing in a State, without discrimi

nation in any respect whatsoever on account of race, creed, or

color, and shall provide for adequate hospital facilities for per

sons unable to pay therefor. Such regulation shall require

that before approval of any application for a hospital or addi

tion to a hospital is recommended by a State agency, assur

ance shall be received by the State from the applicant that (1)

such hospital or addition to a hospital will be made available

to all persons residing in the territorial area of the applicant,

without discrimination in any respect whatsoever on account

of race, creed, or color; and (2) there will be made available

in each such hospital or addition to a hospital a reasonable

volume of hospital services to persons unable to pay therefor,

but exception shall be made if such a requirement is not fea

sible from a financial standpoint.”