Motion for Leave to File and Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 12, 1979

33 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Motion for Leave to File and Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae, 1979. 0f12c55a-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e9712e3-39a5-427d-b0d3-ab5dc189df07/motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-for-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

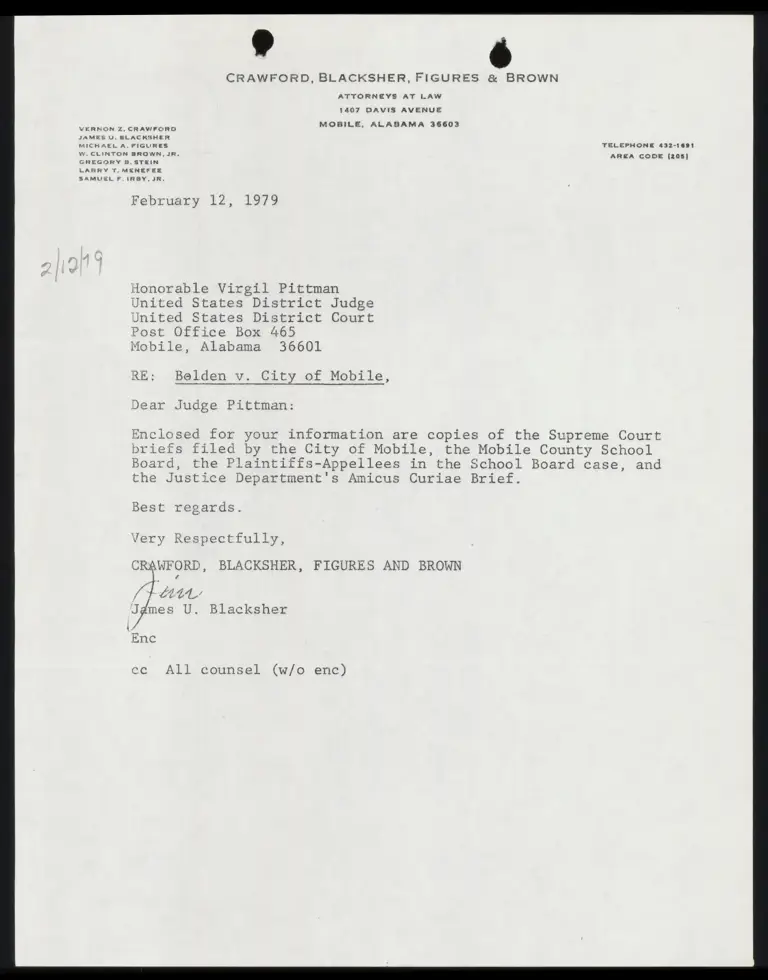

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

: a rw MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

VERNON Z, CRAWFORD

JAMES U, BLACKSHER

MICHAEL A. FIGLIRES TELEPHONE 432-1691

W. CLINTON BROWN, JR. AREA CODE (208)

GREGORY B, STEIN

LARRY T. MENEFEE

SAMUEL F. IRBY, JR.

February 12, 1979

Honorable Virgil Pittman

United States District Judge

United States District Court

Post Office Box 465

Mobile, Alabama 36601

RE: Belden v. City of Mobile,

Dear Judge Pittman:

Enclosed for your information are copies of the Supreme Court

briefs filed by the City of Mobile, the Mobile County School

Board, the Plaintiffs-Appellees in the School Board case, and

the Justice Department's Amicus Curiae Brief.

Best regards.

Very Respectfully,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES AND BROWN

pd

Igmes U. Blacksher

All counsel (w/o enc)

IN THE

Supreme mut of the Wnited States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

- Appellants,

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

AND

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

CHARLES A. BANE

THOMAS D. BARR

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

FRANK R. PARKER

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

Civi. RIGHTS UNDER Law

720 Milner Building

210 South Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

(601) 948-5400

ROBERT A. MURPHY

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CiviL RIGHTS UNDER LAw

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

WILSON - EPES PRINTING CoO., INC. - 789-0096 - WASHINGTON, D.C. 20001

IN THE

Supreme Cut of the uited States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

Vv.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

proposed amicus curiae herein, respectfully seeks leave

of this Court to file the attached brief in order to assist

the Court in resolving the constitutional questions pre-

sented in this voting rights case.

As set forth in the attached brief, the Lawyers’ Com-

mittee has been intimately involved for a number of

years in voting rights litigation on behalf of minority-

race voters, and we have participated, both as amicus

curiae and as the representative of parties, in many of

this Court’s important voting rights cases. The instant

case is of particular concern to us, involving the effect

of at-large voting schemes on the participation of mi-

nority voters in the electoral process. We bring to this

case a familiarity with, and understanding of, the ap-

plicable decisions of this Court. We also bring to this

case—as a result of our extensive litigation in this area

—a close familiarity with the exclusionary purpose and

effect at-large municipal voting has had on minority

participation in municipal government, particularly in

the South where most of our litigation has taken place.

By filing this brief, we wish to present to the Court

a perspective based on our litigation experience in the

South which is not likely to be presented by any of the

parties.

Appellees have consented to the filing of this brief.

Consent was sought from appellants, but not granted.

WHEREFORE, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law respectfully moves that its brief

amicus curiae be filed in this case.

January 10, 1979.

Respectfully submitted,

CHARLES A. BANE

THOMAS D. BARR

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

FRANK R. PARKER

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

Civi RIGHTS UNDER LAw

720 Milner Building

210 South Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

(601) 948-5400

ROBERT A. MURPHY

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CiviL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

E33 EB RE 0 Dien iolesee blame aim Jy

I. AT-LARGE ELECTIONS IN MUNICIPALI-

IL

111.

TIES IN WHICH MINORITY VOTERS HAVE

BEEN DENIED EQUAL ACCESS TO THE

POLITICAL PROCESS AND IN WHICH MI-

NORITY VOTERS HAVE HAD LESS OPPOR-

TUNITY THAN WHITES TO BLECT CITY

COUNCIL MEMBERS OF THEIR CHOICE

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DILUTE, MINI-

MIZE, AND CANCEL OUT BLACK VOTING

SD NG RH iio rziiir te nr isissis setacshasacsssainssrss

AS OUR EXPERIENCE IN MISSISSIPPI IN-

DICATES, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT'S DECI-

SION IN THIS CASE IS CORRECT AND

SHOULD BE AR RMD ci arcoess-rreecicocss

PLAINTIFFS CHALLENGING AT-LARGE

MUNICIPAL VOTING SHOULD NOT BE RE-

QUIRED TO PROVE THAT THE AT-LARGE

SYSTEM WAS ADOPTED FOR A SPECIFIC

RACIAL PURPOSE IF THE PROOF SHOWS

THAT AT-LARGE MUNICIPAL VOTING

HAS BEEN MAINTAINED TO EXCLUDE

BLACK REPRESENTATION OR OPERATES,

IN THE FACE OF A PAST HISTORY OF

EXCLUSION OF MINORITIES FROM THE

POLITICAL PROCESS, TO DENY BLACK

VOTERS THE OPPORTUNITY TO ELECT

CANDIDATES OF THEIRCHOICE ..................

CONCLUSION |... cis rst t-ssrsosoa~srcisess stor siotrrosss

Page

11

16

20

II

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

BL a Sala ee ily 11,43

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) 11

Boker Vv. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ......... c..cnie. 19

Black Voters Vv. McDonough, 565 F.2d 1 (1st Cir.

50g PEER Bet pn LC DM 8

Bolden v. City of Mobile, Ala., 571 F.2d 238 (5th

431 Le HERE a a ee 11

Burns V. Richardson, 384 U.8..73.41966)................ 4

Chapman V..Meier, 420 U.S. I (1975)... .cccoieicinen. 10

City of Richmond Vv. United States, 422 U.S. 358

ES Male a aE SRE 2

Connor. Ny. Finch, 431 1.8. 407 (1977) ..coreinsneerncises 2.10, 15

Corder v. Kirksey, 585 F.2d 708 (5th Cir. 1978) .... 10

Dallas County v. Reese, 421 U.S. 477 (1975).......... 4,9

Dove Vv. Moore, 539 F.2d 1152 (8th Cir. 1976) .... 8

Fast Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424

U.S 830 L10T0Y fi... comicerariciae. red isemine ian bine srs 3,8,10

Fairley v. Patterson and Bunton V. Patterson, de-

cided sub nom. Allen v. State Board of Elections,

BOS U.S. 544 (1960y a. 24

Forison V. Dorsey,.379.1U.8..433 (1965) ................. 4

Georgia Vv. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973) ...___. 3

Kendrick v. Walder, 527 F.2d 44 (7th Cir. 1975) .. 8

Kilgarlin V..Hill, 3806 U.S. 120. (1967) .-....ccorircivmennns 10

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County,

Mississippt, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977), cert.

dented, 434 U.S. 968 £1977) corn. occrenernse imonionys 9

Nashville, C. & St. Louis R. Co. v. Walters, 294

RMSE DR bons BIRO Ce 18

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978) ........ 11

Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976) ........ 8

Parnell v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 563 F.2d

180 (Bh Clr. A077) sueccortier omssrociseitrmpogrivarsssss sion: 8

Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir.

2 50600 BIG IR RE CS TH 8

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ..................... 4, #819

III

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Seals v. Quarterly County Court, 526 F.2d 216 (6th

Cle 1978) «as 8

Stewart v. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206 (N.D. Miss.

By 5,12,13, 14

Washington Vv. Davis, 426 1U.8.229 (1976) ............... 17,18

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) ....4,8,9,12,16

White Vv. Regester, 412 U.S. 7155 (1973) ................ passim

Wise Vv. Lipscomb, No. 77-5629 (June 22, 1978) .._._..... 2,7,10

Zimmer V. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff’d on other grounds sub nom. Fast

Carroll Parish Police Jury v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

686 (1976)... a a 8, 10

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Banzhaf, Multi-Member Electoral Districts—Do

they Violate the “One Man, One Vote” Principle,

73 Yale LJ. 1309:(1966) .... c.cink tii bien oan. 5

Bonapfel, Minority Challenges to At-Large FElec-

tions: The Dilution Problem, 10 Ga. L. Rev. 353

(1876)... a 10

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Multi-

Member Districts and Fair Representation, 120

U. Pal. Bev. 606 (1972) ........ionsi sn ive. 5

Sloane, “Good Government” and the Politics of

Race, 17 SOCIAL PROBLEMS 156 (1969) ......... 5

UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON CIVIL

RIGHTS, POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

coesy. 5, 13

WASHINGTON RESEARCH PROJECT, THE

SHAMEFUL BLIGHT: THE SURVIVAL OF

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN VOTING IN

THR SOUTH (1972)... "= = a

IN THE

Supreme mut of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President

of the United States to involve private attorneys through-

out the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. The Committee’s membership

today includes two former Attorneys General, ten past

Presidents of the American Bar Association, a number

of law school deans, and many of the Nation’s leading

2

lawyers. Through its national office in Washington, D.C.,

and offices in Jackson, Mississippi, and eight other cities,

the Lawyers’ Committee over the past fifteen years has

enlisted the services of over a thousand members of the

private bar in addressing the legal problems of minori-

ties and the poor in voting, employment, education, hous-

ing, municipal services, the administration of justice,

and law enforcement.

In the past, the Lawyers’ Committee has filed briefs

amicus curiae by consent of the parties or by leave of

this Court in a number of important civil rights cases.

The interest of the Lawyers’ Committee in this case

arises from its dedication to and interest in the full

and effective enforcement and administration of the Na-

tion’s constitutional and statutory provisions securing the

voting rights of minorities. As a result of providing

legal representation to litigants in voting rights cases

for the past thirteen years, the Committee has gained

considerable experience and expertise in problems of

racial discrimination relating to the voting rights of

minority citizens, and in the requirements and guaran-

tees of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and

the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Attorneys associated with

the Lawyers’ Committee represented the minority plain-

tiffs in two of the first four cases to reach this Court

on the scope of the requirements of § 5 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, Fairley v. Patterson and Bunton

Vv. Patterson, decided sub nom. Allen v. State Board of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969), and have provided con-

tinuing representation since 1970 to the plaintiff voters

in the Mississippi state legislative reapportionment case,

in which this Court has rendered five decisions in this

decade, the latest of which was Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S.

407 (1977). The Committee also represented the mi-

nority voters in City of Richmond v. United States, 422

U.S. 358 (1975); and, we filed amicus briefs in Wise

3

Vv. Lipscomb, No. 77-529 (June 22, 1978); East Carroll

Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), and

Georgia Vv. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973).

In this case the Committee is interested in (1) the

constitutional and Federal statutory implications of the

exclusion of minority representation in municipal gov-

ernment by at-large municipal voting in majority white

communities, (2) the applicability to at-large municipal

elections, of the principles announced by this Court in

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), that at-large

voting unconstitutionally dilutes black voting strength

when blacks have been denied equal access to the po-

litical process, and (3) the question of the applicability

of the racial purpose requirements to an at-large munici-

pal voting system which has been in effect for a long

time. In addition, attorneys associated with the Jack-

son, Mississippi office of the Lawyers’ Committee cur-

rently have pending four cases challenging at-large mu-

nicipal elections for city council members, and the de-

cision of the Court in this case is likely to have a direct

impact on the decisions in those cases.

Because of our extensive and intimate involvement

in voting rights cases involving state legislatures, coun-

ties, and municipalities, our extensive knowledge of the

case law in the area, and our familiarity with the ex-

clusionary purpose and effect at-large municipal voting

has had on minority participation in municipal govern-

ment, particularly in the South, we have a perspective on

this case which has not been presented by the petitioners,

and which will not be presented in its entirety by the

respondents.

The Lawyers’ Committee therefore files this brief as

friend of the Court urging affirmance of the judgment

below.

4

DISCUSSION

I. AT-LARGE ELECTIONS IN MUNICIPALITIES IN

WHICH MINORITY VOTERS HAVE BEEN DE-

NIED EQUAL ACCESS TO THE POLITICAL

PROCESS AND IN WHICH MINORITY VOTERS

HAVE HAD LESS OPPORTUNITY THAN WHITES

TO ELECT CITY COUNCIL MEMBERS OF THEIR

CHOICE UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DILUTE, MIN-

IMIZE, AND CANCEL OUT BLACK VOTING

STRENGTH.

While at-large elections are “not per se illegal under

the Equal Protection Clause,” Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403

U.S. 124, 142 (1971), the Court has repeatedly held

that at-large voting is unconstitutional when “designedly

or otherwise, a multi-member constituency apportionment

scheme, under the circumstances of a particular case,

would operate to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements of the voting

population.” (emphasis supplied) Burns Vv. Richardson,

384 U.S. 73, 88 (1966) ; Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433,

439 (1965) ; accord, Dallas County Vv. Reese, 421 U.S.

477, 480 (1975); White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 765

(1973) ; Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra, 403 U.S. at 143. In

Fairley v. Patterson, decided sub nom. Allen Vv. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 569 (1969), the Court

in considering whether a switch to at-large county super-

visor elections was subject to Federal preclearance under

§ 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 held:

The right to vote can be affected by a dilution of

voting power as well as by an absolute prohibition

on casting a ballot. See Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

533, 555. Voters who are members of a racial

minority might well be in the majority in one dis-

trict, but in a decided minority in the county as a

whole. This type of change could therefore nullify

their ability to elect the candidate of their choice

just as would prohibiting some of them from voting.

5

In many parts of the South—and possibly elsewhere—

at-large elections ‘“designedly or otherwise” are the last

vestige of racial segregation in voting. Although blacks

and other minorities in the South are now permitted to

register and vote in large numbers—primarily as a

result of the Voting Rights Act of 1965—at-large elec-

tions which dilute minority voting strength “nullify their

ability to elect the candidate of their choice just as would

prohibiting some of them from voting.”

In White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766 (1973), aff’g

in relevant part, Graves V. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704

(W.D. Tex. 1972) (three-judge court), the Court held

that at-large elections unconstitutionally dilute minority

voting strength when plaintiffs have produced

evidence to support findings that the political pro-

cesses leading to nomination and election were not

equally open to participation by the group in ques-

1 WASHINGTON RESEARCH PROJECT, THE SHAMEFUL

BLIGHT: THE SURVIVAL OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN

VOTING IN THE SOUTH 109-26 (1972); UNITED STATES

COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS, POLITICAL PARTICIPA-

TION 21-25 (1968) ; see also Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment:

Multi-M ember Districts and Fair Representation, 120 U. Pa.L. Rev.

666 (1972); Banzhaf, Multi-Member Electoral Districts—Do they

Violate the “One Man, One Vote” Principle, 75 YALE L.J. 1309

(1966). There can be no doubt that in some instances at-large

municipal elections have been instituted for purposes of discrimina-

tion, e.g., Stewart v. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206 (N.D. Miss. 1975)

(three-judge court) (1962 Mississippi statute requiring switch to

at-large municipal voting held unconstitutional as racially moti-

vated). In other instances, the justification advanced is to eliminate

ward politics and to promote government reform, but the effect on

minority participation is equally discriminatory:

In a fundamental sense, the Black American has fallen victim

of governmental reform. In their zeal for efficiency, democratic

government, and the elimination of corruption, the reformers

have led us to new political systems which operate to the detri-

ment of minority groups.

Sloane, “Good Government” and the Politics of Race, 17 SOCIAL

PROBLEMS 156, 174 (1969).

6

tion—that its members had less opportunity than did

other residents in the district to participate in the

political processes and to elect legislators of their

choice.

White held at-large voting for the Texas Legislature in

Dallas County unconstitutional on a showing of (1) ‘“the

history of official racial discrimination in Texas, which

at times touched the right of Negroes to register and

vote and to participate in the democratic processes”; (2)

Texas law “requiring a majority vote as a prerequisite

to nomination in a primary election”; (3) the “so-called

‘place’ rule limiting candidacy for legislative office from

a multi-member district to a specified ‘place’ on the

ticket”; (4) since Reconstruction, only two black can-

didates from Dallas County had been elected to the

House of Representatives, and these were the only two

blacks ever slated by the white-controlled Dallas Com-

mittee for Responsible Government (DCRG); and (5)

the DCRG did not require the support of black voters,

and “did not therefore exhibit good-faith concern for the

political and other needs and aspirations of the Negro

community.” 412 U.S. at 766-67.

The Court made similar findings with respect to

Mexican-American voters in Texas. The Court found

that the Mexican-American community of Bexar County

(San Antonio) was effectively removed from the political

processes on proof that it “had long suffered from, and

continues to suffer from, the results and effects of in-

vidious discrimination and treatment in the fields of

education, employment, economics, health, politics and

others”; that the state poll tax and restrictive voter

registration procedures had foreclosed effective political

participation; and that “the Bexar County legislative

delegation in the House was insufficiently responsive to

Mexican-American interests.” Id. at 767-69. Single-

member legislative districts were required “to remedy

‘the effects of past and present discrimination against

7

Mexican-Americans’ . . . and to bring the community into

the full stream of political life of the county and State

by encouraging their further registration, voting, and

other political activities.” Id. at 769.

White is the first case in which this Court struck

down at-large voting—there in multi-member legislative

districts—for unconstitutional dilution of minority vot-

ing strength. But in Wise v. Lipscomb, 46 U.S.L.W. 4777,

4781 (U.S. June 22, 1978) (No. 77-529), four Justices

noted that the Court had not yet decided whether the

principles of White v. Regester were applicable to munici-

pal governments. We believe that they are, and that no

significant distinction can be made between at-large

legislative voting and at-large municipal voting.

First, every Court of Appeals which has been pre-

sented with the issue has held the principles of White

equally applicable to at-large voting in county and mu-

nicipal government, and has sustained or rejected dilu-

tion challenges to local at-large voting depending on

2 The District Court’s judgment affirmed by this Court also rested

on evidence of racial bloc voting, 343 F. Supp. at 731, 732:

The population of the West Side of San Antonio tends to

vote overwhelmingly for Mexican-American candidates when

running against Anglo-Americans in party primary or special

elections, to split when Mexican-Americans run against each

other, and to support the Democratic Party nominee regardless

of ethnic background in the general elections. The record shows

that the Anglo-Americans tend to vote overwhelmingly against

Mexican-American candidates except in a general election when

they tend to vote for the Democratic Party nominee whoever

he may be although in a somewhat smaller proportion than

they vote for Anglo-American candidates. * * * It is not sug-

gested that minorities have a constitutional right to elect

candidates of their own race, but elections in which minority

candidates have run often provide the best evidence to deter-

mine whether votes are cast on racial lines. All these factors

confirm the fact that race is still an important issue in Bexar

County and that because of it, Mexican-Americans are frozen

into permanent political minorities destined for constant de-

feat at the hands of the controlling political majorities.

8

whether or not the White criteria had been met on the

facts of each individual case. Thus, the White v. Reg-

ester criteria have been applied to local at-large voting

challenges by the First,® Fifth,* Sixth,” Seventh, and

Eighth 7 Circuits.

Second, the reasoning of the Court’s decision in White

V. Regester is sound, and there is no good reason to

limit its application to at-large legislative elections.

Where—as in this case (423 F. Supp. at 393-94) —the

election law of the State applicable to municipal elections

requires at-large, citywide voting, city council members

must receive a majority vote for nomination or election,

and candidates are restricted to a place or number on the

ballot, blacks are effectively excluded from the oppor-

tunity to elect candidates of their choice to city govern-

ment in majority white communities where racial bloc

voting prevails—not “as a function of losing elections,”

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 153 (1971), but as

a result of the “built-in bias” (id.) of the State’s elec-

toral mechanisms. Further, where—as here (423 F.

Supp. at 393) —in the past black citizens have been dis-

enfranchised by racially discriminatory state voter regis-

3 Black Voters v. McDonough, 565 F.2d 1 (1st Cir. 1977) (Boston

City School Committee).

t Parnell v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 563 F.2d 180 (5th Cir.

1977) (parish police jury and school board) ; Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d

1108 (5th Cir. 1976) (Albany, Ga., City Council) ; Perry v. City of

Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th Cir. 1975) (city council) ; Zimmer V.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’d on other

grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish Police Jury v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976) (parish policy jury and school board).

5 Seals v. Quarterly County Court, 526 F.2d 216 (6th Cir. 1975)

(Madison County, Tenn., county governing board).

8 Kendrick Vv. Wolder, 527 F.2d 44 (7th Cir. 1975) (Cairo, li,

City Commission).

7? Dove V. Moore, 539 F.2d 1152 (8th Cir. 1976) (Pine Bluff, Ark.,

City Council).

9

tration statutes and mechanisms, the requirement of at-

large municipal voting under these conditions unconstitu-

tionally perpetuates the past purposeful and intentional

exclusion of blacks from the political and electoral proc-

esses of the municipality, cf. Kirksey v. Board of Su-

pervisors of Hinds County, Mississippi, 554 F.2d 139

(5th Cir. 1977) (en banc), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 968

(1977), and distinguishes the exclusion of the disen-

franchised racial minority from exclusion of other in-

terest groups, cf. Whitcomb v. Chavis, supra, 403 U.S.

at 156. In addition, where—as the proof here shows

(423 F. Supp. at 389-92) —the at-large elected city gov-

ernment has been unresponsive to the needs and interests

of the minority community, the presumption that each

city commissioner represents and serves all of those who

elect him in citywide voting, cf. Dallas County V. Reese,

421 U.S. 477, 480 (1975), is overcome, and the exclusion

of minority representation goes to the heart of the

democratic process:

Racial minorities protest this institutionalized bar

to their effective exercise of political power. They

point out that, because of racial discrimination, they

have been and are being denied adequate educational,

employment, and housing opportunities and conse-

quently have common interests in these substantive

areas which are unique to them because of their race.

In a system dominated by the majority, racial mi-

norities complain, they are powerless to improve their

condition because the government in which they lack

representation and political influence is unconcerned

about their problems. In particular, racial minori-

ties urge that they must be given the opportunity to

elect members of their own race who, having experi-

enced similar difficulties, are more understanding of

the minority’s problems and better able to articulate

the minority’s viewpoint. Noting that in a ward sys-

tem they would be thus represented and able to ex-

ploit their political power, minorities contend that

10

an at-large electoral system which precludes this ac-

cess is invalid: the inability to elect a share of rep-

resentatives substantially proportionate to their num-

bers is alleged to be a denial of the effective rep-

resentation to which they are entitled under the

Constitution.®

Third, no meaningful distinction can be drawn be-

tween at-large legislative voting and at-large municipal

voting. Multi-member legislative districts “in logic of

analysis are merely one form of at-large voting . . .”

Zimmer Vv. McKeithen, supra, 485 F.2d 1315 (Clark, J.,

dissenting). While certain differences may exist in the

evils attributable to at-large legislative elections and

at-large municipal voting,” they are identical in their

one distinguishing feature—both multi-member districts

and citywide municipal voting “[allow] the majority to

defeat the minority on all fronts,” Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386

U.S. 120, 126 (1967) (Douglas, J., concurring). It is this

winner-take-all feature that permits the overrepresenta-

8 Bonapfel, Minority Challenges to At-Large Elections: The Dilu-

tion Problem, 10 Ga. L. Rev. 353, 360 (1976) (footnotes omitted).

9 In Corder Vv. Kirksey, 585 F.2d 708, 713 n. 11 (5th Cir. 1978),

the Fifth Circuit noted that there were certain differences between

multi-member legislative districts and local at-large districts. But

most of the recognized evils of multi-member legislative districts

cited by this Court for preferring single-member districts in court-

ordered legislative reapportionment plans are equally applicable to

at-large municipal voting. In court-ordered plans, single-member

districts are preferred “[b]ecause the practice of mutimember dis-

tricting can contribute to voter confusion, make legislative repre-

sentatives more remote from their constituents, and tend to sub-

merge electoral minorities and overrepresent electoral majorities

. .." Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407, 415 (1977) ; see also, Chapman

V. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 15-19 (1975). All of these disadvantageous

characteristics of multi-member legislative districts are shared by

at-large municipal voting, and the Court has held that single-member

districts are preferred in court-ordered plans in both cases involving

multi-member legislative districts and in cases involving at-large

county and municipal voting. Wise v. Lipscomb, 46 U.S.L.W. 4777,

4779 (U.S. June 22, 1978) (No. 77-529) ; East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, supra.

11

tion of the majority and the exclusion of the minority—

which might gain representation under single-member

districts—under both multi-member legislative districts

and at-large municipal voting.

Indeed, there is a close analogy with malapportioned

voting districts, since both at-large voting and malap-

portioned districts involve claims of dilution of voting

power. Allen Vv. State Board of Elections, supra, 393

U.S. at 569. The Court has not limited dilution claims

involving malapportionment to state legislative districts,

but has applied the dilution criteria based upon nu-

merically unequal districts to all “units of local govern-

ment having general governmental powers over the en-

tire geographic area served by the body,” Avery v. Mid-

land County, 390 U.S. 474, 485 (1968). It would be

anomalous indeed for the Court to sustain dilution chal-

lenges based on malapportionment of municipal voting

districts in the context of municipal voting to allow one

kind of dilution challenge—based on malapportioned mu-

nicipal voting districts—but not to allow another—based

on minimizing and cancelling out black voting strength.

Certainly nothing can be found in the Fourteenth Amend-

ment—which was enacted specifically to protect racial

minorities—which would support such a bizarre dis-

tinction.

II. AS OUR EXPERIENCE IN MISSISSIPPI INDI-

CATES, THE FIFTH CIRCUIT'S DECISION IN

THIS CASE IS CORRECT AND SHOULD BE

AFFIRMED.

The Fifth Circuit correctly decided that an at-large

municipal voting system is unconstitutional when it is

enacted for a racial purpose, maintained for a racial

purpose, or operates to deny the minority community

equal access to the electoral process. Bolden v. City of

Mobile, Ala., 571 F.2d 238 (5th Cir. 1978); see also,

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978). These

legal principles represent a proper application of the

12

holdings in this Court’s prior decisions in Whitcomb Vv.

Chavis, supra, and White Vv. Regester, supra.

The Fifth Circuit’s decision in this case addresses a

serious and continuing problem of exclusion of minority

representation from equal participation in municipal

government which exists throughout the South and pos-

sibly in some Northern communities as well. In Missis-

sippi, where we are familiar with local conditions be-

cause of our extensive voting rights litigation there, at-

large municipal voting has been both instituted and

maintained for purposes of minimizing and cancelling

out black voting strength. In 1962—after the first mas-

sive voter registration drives were getting underway—

the Mississippi Legislature enacted a statute, Miss. Laws,

1962, ch. 537, requiring all code charter municipalities

with a mayor-alderman form of government to switch

from ward to at-large, citywide election of aldermen.

Stewart v. Waller, 404 F. Supp. 206 (N.D. Miss. 1975)

(three-judge court). Prior to 1962, cities with popula-

tions over 10,000 were required to elect six aldermen by

ward and one at-large, and cities with populations under

10,000 had an option of electing four aldermen by ward

and one at-large, or of electing all five aldermen at-

large. An action was filed challenging the -constitu-

tionality of this statute. In 1975, on evidence showing

that “it was a foreseeable certainty that in many wards

in many municipalities the electorate would contain a

majority of black citizens” (404 F. Supp. at 213), and

that the author of the statute argued during the legis-

lative debates that “this is needed to maintain our south-

ern way of life” (id.), a three-judge District Court de-

clared the statute violative of the Fourteenth and Fif-

teenth Amendments for the reason that it was designed

“to forestall the possibility that black aldermen might in

some instances win election” and was passed with the

“intent to thwart the election of minority candidates

13

to the office of alderman.” Stewart v. Waller, supra,

404 F. Supp. at 214.

As a result of the Stewart injunction enjoining en-

forcement of the 1962 statute, 29 cities which had

switched to at-large elections were required to revert

to ward elections. In the 1977 municipal elections—the

first since the Stewart decision—twenty black aldermen

were elected for the first time to formerly all-white boards

of aldermen in fourteen cities covered by the Stewart

decree.

Similarly, after the passage of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, allowing black citizens to

register and vote in large numbers in the South, the

Mississippi Legislature enacted several statutes requir-

ing and allowing county boards of supervisors and county

boards of education to switch from district to at-

large, countywide elections. See United States Commis-

sion on Civil Rights, POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

21-23 (1968). In Allen v. State Board of Elections,

supra, 393 U.S. at 569-70, this Court held that such

statutes were covered by the Federal preclearance re-

quirement of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. §1973c, in part because of their potential for

diluting and minimizing minority voting strength. The

statutes were submitted to the Attorney General of the

United States, and an objection was lodged based upon

dilution of black voting strength.

These statutes were enacted purposefully and inten-

tionally to prevent the election of black candidates and

to deprive black voters of the opportunity to elect can-

didates of their choice. But as here when a municipality

maintains an at-large, citywide voting scheme for the

purpose of diluting black voting strength, the result is

the same and the constitutional rights of minority voters

are equally violated. In Mississippi, the Lawyers’ Com-

14

mittee has represented black voters in filing at-large

municipal voting challenges against ten Mississippi cities,

involving the cities of Aberdeen, Columbus, Greenville,

Greenwood, Hattiesburg, Hazlehurst, Jackson, Picayune,

West Point, and Yazoo City. In each instance, all mem-

bers of the city council were elected in at-large, citywide

voting, and despite the fact black candidates had run for

the city council, and blacks constituted more than 20%

of the voting population (but less than a registered ma-

jority), in only one instance! had any black candi-

date been elected to the city council when the suit

was filed. These municipalities—and others—are not

covered by the injunction issued in Stewart v. Waller,

supra, either because they have commission forms of

government or because they are private charter munici-

palities in which their at-large voting systems are not

mandated by state statute. Like Mobile, some of these

municipalities instituted at-large voting systems in the

early 1900’s; others are of more recent vintage. But

in each case, the maintenance of at-large municipal vot-

ing has resulted in the almost total exclusion of any

black representation in city government, although black

persons constitute 20% or more of the city population.

To the best of our knowledge, of the more than 1,300

elected city council members in Mississippi, only seven

10 In 1974 Mrs. Sarah Johnson was elected to the six-person Green-

ville City Council with less than a majority of the vote in a three-

person race. After these suits were filed, two black council members

were elected in at-large voting in Greenville (Mrs. Johnson was

reelected) and Picayune.

11 Because of White Vv. Regester and other related Fifth Circuit

decisions, six of the ten cases have been settled and single-member

ward districting plans have been substituted for all at-large elec-

tions. In each case, the new ward plans provide for two majority

black wards. In two cases, ward election plans went into effect for

the 1977 and 1978 municipal elections in West Point and Yazoo

City; in West Point one black alderman was elected to the pre-

viously all-white board of aldermen and in Yazoo City two black

aldermen were elected for the first time.

15

black city council members have been elected in at-large

voting from white majority constituencies or in ward

voting from white majority wards.

Under circumstances such as these, public officials in

the South can hardly claim to be unaware that the main-

tenance of at-large municipal voting schemes, particu-

larly in face of a recent past history of exclusion of black

citizens from the political process through disenfranchise-

ment, operates to dilute, minimize, and cancel out black

voting strength and to exclude the possibility of black

representation in municipal government, whatever the

particular form that municipal government may take.

In the circumstances of this case, the constitutional

claims of black voters and the findings of the District

Court that at-large municipal elections have been main-

tained for a racially discriminatory purpose and have

operated to exclude black representation should outweigh

the purely administrative claims of the city that a city-

wide perspective is needed in city government. In Connor

Vv. Finch, supra, the Mississippi Legislative reapportion-

ment case, the State official defendants made similar

claims that at-large voting in multi-member legislative

districts were needed to maintain a countywide per-

spective in the Legislature, but these arguments were

rejected by the Court last Term in rejecting pleas for

multi-member districts in a court-ordered plan, Connor

v. Finch, supra, 431 U.S. at 415. Many Mississippi

municipalities have been forced to abolish at-large vot-

ing and revert to ward elections, but no claim has been

made that this has destroyed or seriously impaired the

orderly functioning of municipal government.

16

ITI. PLAINTIFFS CHALLENGING AT-LARGE MUNICI-

PAL VOTING FOR DILUTION OF BLACK VOTING

STRENGTH SHOULD NOT BE REQUIRED TO

PROVE THAT THE AT-LARGE SYSTEM WAS

ADOPTED FOR A SPECIFIC RACIAL PURPOSE IF

THE PROOF SHOWS THAT AT-LARGE MUNICI-

PAL VOTING HAS BEEN MAINTAINED TO

EXCLUDE BLACK REPRESENTATION OR OPER-

ATES, IN THE FACE OF A PAST HISTORY OF

EXCLUSION OF MINORITIES FROM THE POLITI-

CAL PROCESS, TO DENY BLACK VOTERS THE

OPPORTUNITY TO ELECT CANDIDATES OF

THEIR CHOICE.

In White v. Regester, supra, a unanimous Court held

that at-large legislative voting in multi-member districts

is unconstitutional if plaintiffs produce evidence (412

U.S. at 766)

that the political processes leading to nomination and

election were not equally open to participation by the

group in question—that its members had less op-

portunity than did other residents in the district to

participate in the political processes and to elect

legislators of their choice. Whitcomb v. Chavis, su-

pra, at 149-50.

In neither Whitcomb nor White did the Court establish

a specific requirement that plaintiffs must prove that

the at-large system had been instituted for a racially

discriminatory purpose, if the proof showed that at-large

voting had operated to deny minority citizens an equal

opportunity to participate in the political and electoral

processes. Therefore, there seems to be no way for this

Court to reverse the decision of the Fifth Circuit in

this case without overruling this Court’s unanimous de-

cision in White.

In cases such as this, where the at-large voting scheme

was adopted with the commission form of government in

17

1911, a requirement that plaintiffs prove specific racial

intent with the adoption of at-large elections would place

an impossible burden on minority plaintiffs. Virtually

no witnesses to the change would be alive today, and

newspaper accounts may be nonexistent or unreliable.

Nor do this Court’s subsequent decisions governing the

Fourteenth Amendment racial purpose requirement re-

quire such a burden. Thus, in Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229, 241-42 (1976), this Court was careful to say:

This is not to say that the necessary diserimina-

tory racial purpose must be express or appear on

the face of the statute, or that a law’s disproportion-

ate impact is irrelevant in cases involving Consti-

tution-based claims of racial discrimination. A stat-

ute, otherwise neutral on its face, must not be ap-

plied so as invidiously to discriminate on the basis

of race. Yick Wo. v. Hopkins, 118 US 356 (1886).

It is clear from the cases dealing with racial

discrimination in the selection of juries that the

systematic exclusion of Negroes is itself such an

“unequal application of the law . . . as to show

intentional discrimination.” Akins v. Texas, supra,

at 404. Smith v, Texas, 311 US 128 (1940) ; Pierre

Vv. Louisiana, 306 US 354 (1939) ; Neal v. Delaware,

103 US 370 (1881). A prima facie case of discrim-

inatory purpose may be proved as well by the ab-

sence of Negroes on a particular jury combined with

the failure of the jury commissioners to be informed

of eligible Negro jurors in a community, Hill Vv.

Texas, 316 US 400 (1942), or with racial non-

neutral selection procedures, Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 US 625 (1972); Avery Vv. Georgia, 345 US 559

(1953) ; Whitus v. Georgia, 385 US 545 (1967).

* * * *

Necessarily, an invidious discriminatory purpose

may often be inferred from the totality of the rele-

vant facts, including the fact, if it is true, that the

18

law bears more heavily on one race than another.

It is also not infrequently true that the discrimina-

tory impact—in the jury cases for example, the total

of seriously disproportionate exclusion of Negroes

from jury venires—may for all practical purposes

demonstrate unconstitutionality because in various

circumstances the discrimination is very difficult to

explain on nonracial grounds.

In looking at the scheme at issue here, both the Dis-

trict Court, after “an intensely local appraisal of [its]

design and impact”, White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S.

at 769, and the Court of Appeals were convinced that

the evidence clearly demonstrated that at-large voting

in Mobile had been maintained for a racial discrimina-

tory purpose. It has operated for almost 70 years to

exclude black representation totally from Mobile’s gov-

erning body, and certainly the City Fathers could not be

ignorant of this preeminent fact. As Mr. Justice Stevens

wrote in his concurring opinion in Washington v. Davis,

supra, 426 U.S. at 253:

Frequently the most probative evidence of intent will

be objective evidence of what actually happened

rather than evidence describing the subjective state

of mind of the actor. For normally the actor is

presumed to have intended the natural consequences

of his deeds.

A requirement that plaintiffs must prove intentional

discrimination with the enactment of at-large voting

schemes also overlooks the firmly established principle of

constitutional law that a statute or official action may be

constitutional at the time it was adopted, but may be-

come unconstitutional over time as conditions change.

“A statute valid when enacted may become invalid by

change in the conditions to which it is applied.” Nash-

ville, C. & St. Louis R. Co. v. Walters, 294 U.S. 405,

415 (1935). Thus, in the reapportionment cases, a legis-

19

lative reapportionment plan which provided equi-populous

and perfectly valid districts when adopted may become

unconstitutional over time as a result of legislative in-

action in not responding to shifts of population which

render the legislative districts malapportioned. Reynolds

Vv. Sims, 377 U.8. 533 (1964); Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S.

186, 192-93 (1962).

Thus, in this case, even if the at-large voting scheme

was adopted in 1911 in a “race-proof” circumstance in

which there was no racial intent because Mobile blacks

were denied the right to vote, nevertheless the at-large

scheme became unconstitutional through legislative inac-

tion as blacks were later permitted to register and vote

and the city commission recognized that at-large elections

operated completely to deny black voters of Mobile the

opportunity to elect city council members of their choice

and to exclude black representation on the Mobile city

commission.

20

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

CHARLES A. BANE

THOMAS D. BARR

Co-Chairmen

NORMAN REDLICH

Trustee

FRANK R. PARKER

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

Civi. RIGHTS UNDER LAw

720 Milner Building

210 South Lamar Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

(601) 948-5400

ROBERT A. MURPHY

Staff Attorney

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

Civi. RIGHTS UNDER LAW

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae