Richmond School Board v Board of Education of Virginia Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1973

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond School Board v Board of Education of Virginia Brief Amicus Curiae, 1973. 3f5a9d37-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8ec6fe72-6a32-4411-80ec-1b337382486c/richmond-school-board-v-board-of-education-of-virginia-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

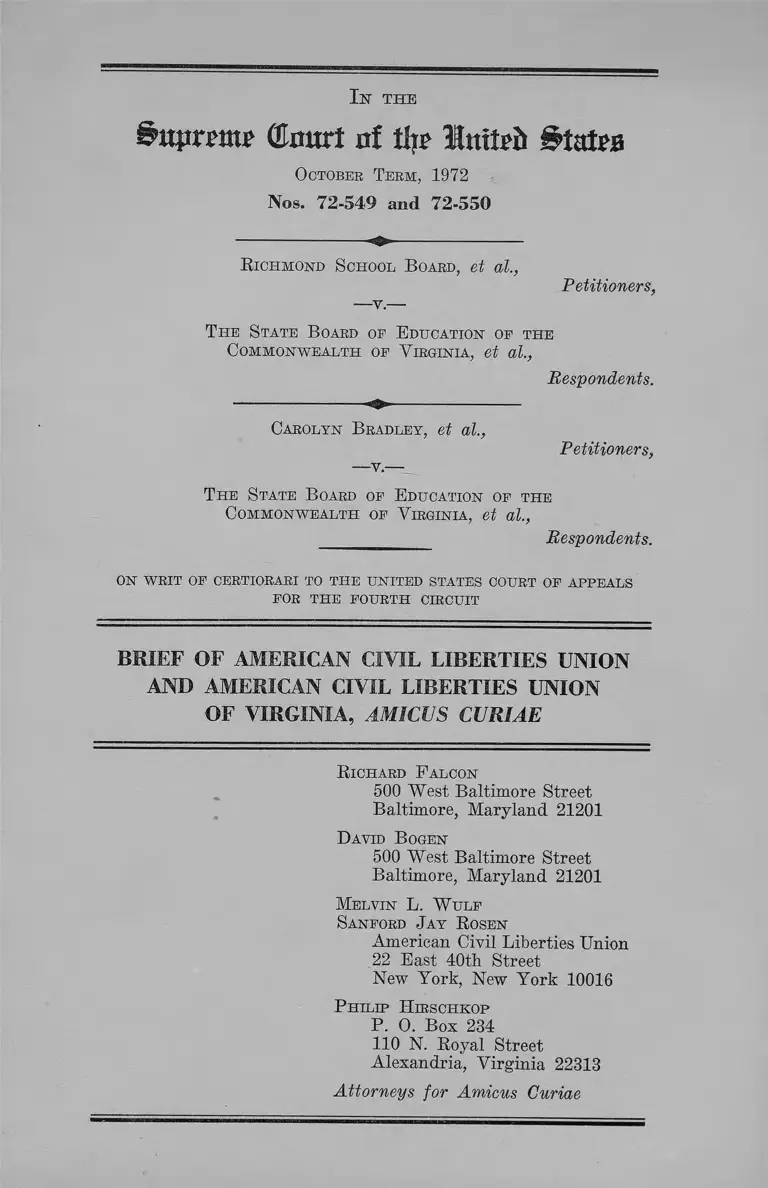

In the

©curt of tljT United States

October Term, 1972

Nos. 72-549 and 72-550

Richmond School B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

T he State B oard of Education of the

Commonwealth of V irginia, et al.,

Respondents.

Carolyn B radley, et al.,

— V .— :

Petitioners,

The State B oard of E ducation of the

Commonwealth of V irginia, et al.,

____ _ Respondents.

on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals

for the fourth circuit

BRIEF OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AND AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

OF VIRGINIA, AMICUS CURIAE

R ichard F alcon

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

David B ogen

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Melvin L. W ulf

Sanford Jay R osen

American Civil Liberties Union

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

P hilip H irschkop

P. O. Box 234

110 N. Royal Street

Alexandria, Virginia 22313

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

I N D E X

Interest of Amicus Curiae ................................................ 2

A rgument ................................................................................ 3

I. The children of metropolitan Richmond are de

nied equal educational opportunity because their

schools are racially segregated............................... 3

II. The State of Virginia has denied plaintiffs the

equal protection of the law s................................. 7

A. The State Has Created the Segregated School

System ................ 7

B. The School Boundary Lines Are Unconstitu

tional Because They Operate to Discriminate

on the Basis of Race and Are Not Justified

by a Compelling State Interest..................... 8

C. The State Cannot Use Political Boundary

Lines to Limit the Federal Courts’ Remedial

Power Because the State Has Caused the

Division of the Races by Those L ines........... 13

Conclusion........................ 16

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968) ................. 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....3,4, 6,

8,14

PAGE

II

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, 426 F.2d

1035 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................................................ 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................... 15

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) ....... .......................... . 9

Glaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) .... 10

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ......................... ...... ’....................... 4

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......10,13

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir.

1971) .................................................................................. 9

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S.

940 (1969) ........................................................................ 9

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968) ........... 9

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ............................. 11

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ..... 11

Monroe v. Bd. of Comm’rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d 1005

(6th Cir. 1970) ................................................................ 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .................................................7,13,14,15

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 395

U.S. 907 (1969) .............................................................. 9

PAGE

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................... 15

United States v. Scotland Neck, 92 S. Ct. 2214 (1972) .... 11

Wright v. City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) ........... 11

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution

Thirteenth Amendment.............................................. 2

Fourteenth Amendment .......................... ............. 2, 8,15

Fifteenth Amendment ....... 2

Federal Statute

Title AMI of the Civil Plights Act of 1964 ....... ........... 10

State Statute

Ya. Code §22-30 ....... ....................................................... 7

Other Authorities:

Cahn, Law in the Consumer Perspective, 112 U. Pa. L.

Eev. 1 (1963) .................................................................... 4

Cahn, The Predicament of Democratic Man (1961) .... 4

Ill

PAGE

I n th e

(Emtrt nf % Imfrd l&atea

October Term, 1972

Nos. 72-549 and 72-550

R ichmond School B oard, et al.,

Petitioners,

T he State B oard of E ducation of the

Commonwealth of V irginia, et al.,

Respondents.

Carolyn Bradley, et al.,

—v.-

Petitioners,

T he State B oard of Education of the

Commonwealth of V irginia, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AND AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

OF VIRGINIA, AMICUS CURIAE

2

Interest of Amicus Curiae

The American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU of

Virginia have secured the consent of the parties to the filing

of the attached brief amicus curiae. The letters of consent

have been filed with the Clerk.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a nation-wide non

partisan organization of over 180,000 members dedicated

solely to preservation of the liberties safeguarded by the

Bill of Rights and the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to

the United States Constitution. The American Civil Liber

ties Union of Virginia is a state affiliate of the ACLU.

The ACLU and the ACLU of Virginia have been particu

larly concerned with the pervasive effects of racial discrimi

nation and segregation on American society. They partici

pate in numerous law suits challenging racial discrimina

tion and segregation. They take the position that effective

racial integration of the public schools is a necessary pre

requisite to the full and equal protection of the laws for

Americans of all races and colors.

In this brief, the ACLU and the ACLU of Virginia pro

vide additional focus on the issues in this case which go well

beyond the facts of the particular case. They hope thereby

to place these issues in the larger perspective.

3

ARGUMENT

This latest aspect of an old school desegregation snit in

volves the equitable powers of the federal courts to give

full and meaningful relief against the continued effects of

de jure school segregation. Within its record, the case pre

sents questions concerning the power of federal courts to

fashion remedies that consolidate school systems that are

separated by lines drawn by state government to secure

non-education interests. For in this case, the petitioners

were ordered by the District Court below to consolidate, for

the purpose of creating a unitary integrated school system,

the effectively segregated separate school systems of the

City of Richmond and the adjacent Chesterfield and Hen

rico counties. The Court of Appeals reversed. In this brief

we take the position that the decision of the District Court

was eminently sound—indeed it is required by the princi

ples contained in decisions of this Court—and it should

be reinstated.

I.

The children of metropolitan Richmond are denied

equal educational opportunity because their schools are

racially segregated.

“ Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954).

“ To separate [black students] . . . generates a feeling of

inferiority as to their status in the community that may

affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be

undone. . . . Segregation with the sanction of law, there

fore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental

4

development of Negro children and to deprive them of some

of the benefits they would receive in a racial [ly] integrated

school system.” Id. at 494.

We submit that at the heart of the Brown principle is

what Edmund Cahn once labeled as the “ consumer perspec

tive,” Cahn, Law in the Consumer Perspective, 112 U. Pa.

L. R ev . 1 (1963); Cahn, The Predicament of Democratic

Man (1961). The “ consumer perspective” simply insists

that the most valid judgment which can be given about

institutions is given by those people whom they are in

tended to serve—i.e., the “ consumer” of that institution’s

services; in this case, black students of segregated schools.

If schools are identifiably “black” or “white,” if they

are more than “ just schools,” Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 442 (1968), the

injury so zealously to be guarded against under Brown

occurs. And the identifiability of schools, together with

the resultant injury occasioned by them, is largely a matter

of a child’s perception. If a child can say (or see or feel)

“ This is one of Richmond’s black schools—and this is one

of Richmond’s white schools,” the school is, within the

meaning of Brown and its progeny, a segregated school.

Given the factual context of this case, a child attending

any metropolitan Richmond school knows whether his

school is a white one or a black one. He also probably

lives within a half hour of the center of the city. Either

his parents or his neighbor’s parents work within the city

limits. No matter where he lives in the metropolitan area,

the child will go to the hospital in the center of the city

if he is ill, and his parents are likely to go into the city

center for entertainment. There are no definite natural

5

geographical boundary lines which divide up the city, and

the political lines constantly shift with each new annex

ation. The only clear physical demarcation between vari

ous parts of the metropolitan area is that people living

near the center of the city are predominantly black and

people living further away are predominantly white; or,

to put it in terms of the child’s perspective—people living

near the center attend “black” schools, and people living

further away attend “white” schools.

The population of the metropolitan Richmond area is

approximately 33% black and 67% white, and this ratio

has remained fairly constant over the past decade. If a

child were in a school with a similar proportion of black

and white students, he would not perceive it as “black”

or “white” but as reflecting the metropolitan Richmond

society in which he lives. Thus, if we assume that only

schools with student bodies of 20-40% black would reflect

Richmond society and thus would not be identifiable by

the child as a “white” school or a “ black” school, all the

high school students and 90% of all elementary and middle

school students attend schools in the metropolitan Rich

mond area identifiable by them as “black” or “white.” The

social cohesiveness of the metropolitan area and physical

proximity further assure such identification. Often high

schools with a student body which is more than 75% black

are located within four miles of high schools which are

more than 80% white.

The black child, the “ consumer,” who attends schools

in Richmond perceives well enough that the schools are

either “black” or “white” schools. And it cannot be said

that the child’s perception is incorrect. The State of Vir

ginia has historically used every means within its control

6

to assure whites that their schools will remain white and

to convince blacks that they will never attend any bnt

black schools. Given this history, the State’s latest refusal

to desegregate its schools effectively is hardly surprising.

Thus, until the remedial hearings in this case were pend

ing, Virginia could and often did ignore political subdi

vision boundaries in setting up school districts. And the

State exercised this power for every reason conceivable,

including the furthering of segregation. When it was sug

gested that Virginia again exercise this power, but now to

aid desegregation, the State responded by legislation pur

porting to divest itself of authority to act.

Nineteen years after Brown, not only today’s black

school children but their parents who were themselves

school children in 1954 cannot help but understand full

well the State’s position when they take their children to

one of “ Richmond’s” black schools. Despite promises,

claims and hopes to the contrary, nothing can more elo

quently remind them of “ their place” than escorting their

child to a school that remains what it always was—a black

school designed to serve black children.

When almost every school in an area can be seen to be

a “ black” school or a “ white” school, it is obvious that the

schools are segregated. That this segregation is caused

by the state’s maintenance of evanescent boundaries does

not alter the child’s perception, his injury or the segre

gation. Indeed, plaintiffs produced a number of witnesses

to testify to the actual educational harm done by this

separation of the races. However, such evidence should

not have been necessary because this Court has recognized

for almost two decades that “ Separate educational facilities

are inherently unequal.” Brown v. Board of Education,

supra, 347 U.S. at 495.

7

The State of Virginia has denied plaintiffs the equal

protection of the laws.

A. The State Has Created the Segregated School System.

State law creates and defines the boundaries of cities

and counties. Such boundaries are often useful for the

administration of many matters, but they need not coincide

with school division boundaries. In fact, when this suit

was instituted, there were a number of school divisions

which included several political units in Virginia, and Vir

ginia law permitted the State Board to consolidate school

districts even if consolidation overlapped such political

lines. Metropolitan school districts overlapping political

lines are not uncommon elsewhere. For example, the City

of Charlotte, North Carolina, and the County of Mecklen

burg comprise a single school system. See Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971). Nevertheless, after institution of this litigation,

Virginia state law was changed and now requires the State

Board to divide the state into school divisions according

to county and city boundary lines, unless the school boards

and governing bodies of the political units affected agree

to a joint school division. Va. Code sec. 22-30. To the

extent that the State has delegated to local officials the

power to determine the boundaries of the administrative

units for schools, the exercise of those powers is still the

State’s responsibility and they must be exercised in con

formity with the state’s constitutional obligations. Regard

less of the legal mechanism, the result of that exercise

of power in this case is clear—segregated schools. Having

II.

8

created a segregated school system and having refused to

exercise that power in a manner that would desegregate

it, the State of Virginia and the Counties of Henrico and

Chesterfield and the City of Richmond have violated their

constitutional duty under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The question in this case, therefore, is not whether state

action has resulted in a segregated school system—that

clearly has occurred. Rather, the question is, having acted

in such a manner as to segregate the races in fact, can the

State demonstrate justification of a sufficiently compelling

nature so as to excuse the effects of its actions? If such

justification does not exist, then the school system is

segregated within the meaning of Brown and the equity

powers of the District Court below were properly applied

to remedy the resultant segregation.

The Court of Appeals did not discuss this question. Ap

plying the wrong legal rules, they instead deemed the rele

vant question to be the existence or non-existence of “ racial

motivation” or “ segregative intent” as an explanation for

the Respondents’ behavior. This was error.

B. The School Boundary Lines Are Unconstitutional Because

They Operate to Discriminate on the Basis of Race and

Are TSot Justified by a Compelling State Interest.

Although there are sometimes no obvious criteria for

drawing lines, it is still useful to draw a line. This is the

case with the political boundary lines in the Richmond area.

There are no natural geographical boundaries dividing the

area, and the lines which are imposed are flexible and sub

ject to constant change through annexation proceedings.

These lines are drawn to facilitate various political and

social functions. But the criteria on which the lines are

9

based are arbitrary, at least in the sense of whimsical.

Such arbitrary lines are properly viewed with suspicion

when their effect is to disadvantage blacks. Thus, courts

have not permitted school attendance lines to be drawn

around a residentially segregated neighborhood when other

attendance zones are just as feasible. Brewer v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

Even attendance zones which follow natural or historical

boundaries have been struck down when they operate to

separate the races. See Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal

■Separate School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969); United States v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 395 U.S. 907 (1969); Clark v. Board of

Education of Little Bock, 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970);

and Monroe v. Bd. of Comm’rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d 1005

(6th Cir. 1970). See also Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971).

If the effect of the line drawing is racial segregation

and the justification is weak, there is no need to probe

the psychological motivation of a legislature and determine

whether there was in fact a racial purpose. Anyone in

volved in such a classification will readily perceive that

they are treated unequally, and courts will agree with the

perception. See Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th

Cir. 1968); Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th

Cir. 1971).

Where the effect of a classification is to separate the

races, persons subject to the classification are likely to be

severely harmed regardless of whether the classification

was overtly on racial grounds or not. They should not be

put to the burden of demonstrating an actual racial mo

10

tive7 intent or purpose. Further, it may prove impossible

to prevent deliberate racial discrimination if the discrimi

nator need only cite some rational basis not directly and

obviously connected with race to support his action. Indi

viduals and states then need only search for a slight ap

parent nonracial basis to continue segregation as before.

Unless the state is forced to demonstrate substantial rea

sons for action which has a racial effect adverse to minority

group members, the state can continue a policy of segre

gation behind a facade of neutrality.

This Court has construed statutes prohibiting racial

discrimination in voting and employment from this per

spective. See Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S.

285 (1969). In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971), an employer used a standardized test for hiring

and promotion decisions. The district court found there

was no racial purpose or invidious intent in adopting the

test although whites generally did better than blacks in

taking it, and by a split decision the Fourth Circuit Court

of Appeals affirmed. Nevertheless, this Court found that

the use of the test violated Title YII of the Civil Eights

Act of 1964 which made it unlawful for an employer “ to

limit, segregate, or classify his employees in any way which

would deprive . . . any individual of employment oppor

tunities . . . because of such individual’s race.” The Court

ruled that an employment test could be used only if it was

in fact related to performance of the job, and that the

employer’s motive in using the test was not the significant

question.

The issue in cases of racial discrimination thus at least

becomes whether the classification or boundary line that

operates to discriminate against blacks is justified by a

1 1

compelling non-racial state interest. See e.g., Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 9 (1967); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379

U.S. 184 (1964).

In the instant case, when effect rather than “ intent” is

considered, and when Virginia’s professed “ justifications”

are weighed to determine their compelling nature, it be

comes clear that consolidation of these school districts is

not beyond the remedial powers of a federal district court.

Indeed, as Judge Winter pointed out in dissent below, this

case is but the “ obverse of the same coin” presented in

the companion cases of Wright v. City of Emporia, 407

U.S. 451 (1972) and United States v. Scotland Neck, 92

S. Ct. 2214 (1972). There, as here, the Court of Appeals

below applied the incorrect test—“ segregative intent.” In

those cases the Court of Appeals permitted one district to

be “ split” into two school districts, ignoring all the while

the segregative effects of such splitting. There, as here,

focus on “ segregative intent” rather than on “ effect” led

the Court of Appeals to conclude that no constitutional

deprivation resulted despite demonstrable segregative ef

fect. This Court reversed, holding that effect, not intent,

was the proper test and that choice of a less effective

alternative to desegregate schools in the face of available

and proven effective alternatives placed a heavy burden

of justification on the state. There, as here, no such com

pelling justification can be professed.

Whatever the State of Virginia’s interest in maintaining

the political boundary lines of Richmond City, Henrico

County and Chesterfield County, it has no compelling in

terest in utilizing those lines for school administrative

zones which result in segregated schools.

12

First, the State ignored political boundary lines to im

plement its earlier policy of segregation. From 1940

through 1968 at least four regional all-black schools were

operated in the State. During this period many Virginia

children were bused across county lines because the near

est school of their race was located in another county.

Further, the State’s tuition grant system enabled children

to transfer out of their county school into one elsewhere,

even in another state, where the children were of the same

race.

Second, political boundary lines have often been ignored

in the past to further other educational purposes. Bieh-

mond, Henrico and Chesterfield have cooperated in a train

ing center for mentally retarded children and, with two

other counties, in operating a mathematics-science center.

On January 3, 1968, the State Board of Education resolved

that “ effective consolidation of school divisions is a pre

requisite to quality public education in many areas of the

state.” Bedford County and Bedford City were thus al

lowed to form a single school division. Fairfax City and

Fairfax County, while remaining separate school divisions,

operate together under a contract with the County edu

cating the city children.

The historic practice of combining several political sub

divisions into one school division demonstrates that there

is no compelling reason to maintain separate school dis

tricts and that the State of Virginia has not in the past

considered the reasons offered in this case to be “ com

pelling.” Separate districts are clearly not necessary to

give residents a voice in the education of their children.

Nor are they necessary to assure the taxpayer that his

money is being used for schools which his children attend.

13

The contract method of joint operation would also assure

the taxpayer that his moneys went to the education of his

children. Since there is no compelling reason to maintain

these school boundary lines which separate children by

race, they should be struck down.

C. The State Cannot Use Political Boundary Lines to Limit

the Federal Courts’ Remedial Power Because the State Has

Caused the Division of the Races by Those Lines.

Virginia has for many years operated a dual system in

all the schools of the state. “Because they are Negroes,

petitioners have long received inferior education in seg

regated schools, and this Court expressly recognized these

differences in Gaston County v. United States.” Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. at 430. As the trial judge

pointed out in this case, inferior education leads to re

stricted job opportunities; unskilled employment leads to

restricted ability to choose a home. Thus, the segregated

schools of the past started a pattern which largely re

stricts blacks to the center of the urban area. Assuming

therefore that there was no significant racial distinction

when the boundary lines were drawn, the state policy of

segregated education throughout most of this century has

helped create the racial division which the lines now mark.

Segregated schools also contributed to the present pat

terns of residential segregation in other ways. “People

gravitate toward school facilities, just as schools are lo

cated in response to the needs of people. The location of

schools may thus influence the patterns of residential de

velopment of a metropolitan area and have important im

pact on composition of inner city neighborhoods.” Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

at 20-21.

14

The State of Virginia contributed to the creation of resi

dential segregation in many other ways as well. The State

for many years enforced restrictive covenants, thereby

encouraging people to impose them on the land to such an

extent that much of the land in the metropolitan Richmond

area today has restrictive covenants in earlier deeds. No

tation of such a covenant was still common in title searches

until within the last few years, even though the covenant

could not be constitutionally enforced. Public housing was

sited and occupied on the basis of race until recently. The

counties provided schools, roads, zoning and development

approval for the rapid growth of the white population in

the county at the expense of the city, without making any

attempt to assure that the development it made possible

was integrated.

Even when state law no longer required absolute racial

separation in the schools, and the massive resistance of

Virginia to the court orders in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion had diminished, schools were still sited to produce

segregation. As the trial judge found, “ Construction in

both counties has tended to correspond with the develop

ment of white and black residential areas, and in fact was

so intended. . . . New construction was planned for black

schools in the county without regard to the possibility of

accommodating an expanding black pupil population in

white schools.” These acts in furtherance of segregated

schools are within the power of the district court to correct.

See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

supra.

The State ignored the boundary lines dividing the city

from the counties in pursuing a policy of school and resi

15

dential segregation which ultimately drove the blacks into

the city and the whites into the counties. It should not be

permitted to use a boundary ignored to create segregation

in order to frustrate remedial measures for the earlier

segregation. See United States v. Indianola Municipal Sep

arate School District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969).

It is encouraging to the principles of the Fourteenth

Amendment that the state has not by its policies made

integration impossible. The order of the trial judge demon

strates that feasible remedial measures can be implemented.

See Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education,

supra. The area involved is not so great nor is the addi

tional transportation so significant as to hamper the educa

tion process if this Court affirms the consolidation order.

Indeed, it is noteworthy that the strongest resistance to this

order comes from the counties (the City of Richmond is

a party plaintiff) where busing is commonplace because of

the lower population density. But State-created segregation

should not be tolerated, especially where its justification

lies in arbitrary lines whose specific location serves only to

mark off areas according to race. Nor should the mandate

of the Constitution be circumvented because of any public

outcry over court orders. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

(1958).

1 6

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in this brief, as well as in the

opinion of the district court below, the judgment of

the court below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

R ichard F alcon

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

David B ogen

500 West Baltimore Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21201

Melvin L. W ule

Sanford Jay R osen

American Civil Liberties Union

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

P hilip H irschkop

P. O. Box 234

110 N. Royal Street

Alexandria, Virginia 22313

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

March 1973

RECORD PRESS, INC., 95 MORTON ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014— (212) 243-5775

10608 CROSSING CREEK RD„ POTOMAC, MD. 20854— (301) 299-7775

ffiSgUlps* 38