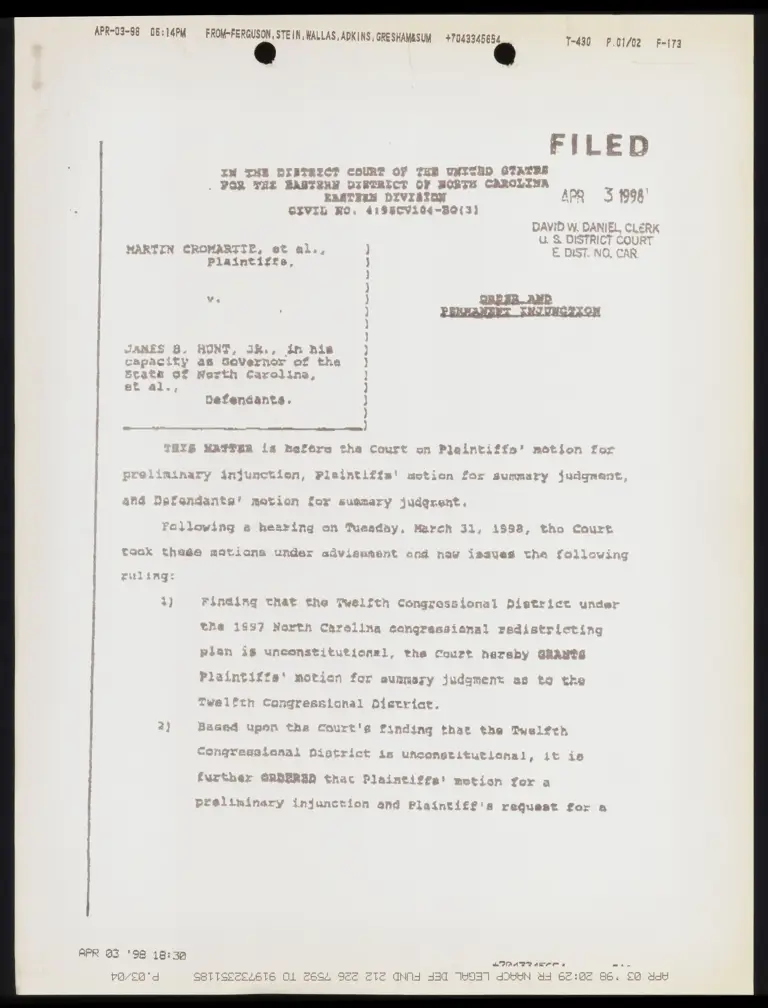

Order and Permanent Injunction

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1998

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Order and Permanent Injunction, 1998. e392a4f0-de0e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8ed7ab1a-4f3f-4f64-8756-e19ccafd4d2e/order-and-permanent-injunction. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

AFR-03-38 08:14PM FROM-FERGUSON. STEIN, KALLAS, ADKINS, GRESHAMBSUM +7043345654 T-430 P.01/02 F-173

LES W i B Hod

4

Ln ¥

EL EBNGall sd

- a vie ST

I

F

Eg

NE Ce fh

+ 3"

=

% ; ey & % a Sed or ob Lib CE aL §

i 3} — =f of wlll

£ ig i

3

5 8d + aad -

ni

. |

3 B

op =

je AAR Fe & En 7. Se un

= i =

E Tt, I W *»¢ mRgrabh yo 1 _ a. - © Ba S00 9

F = of 3 ¥ og ? . a4 i al

§

v . of gem go | 4

- | = 5 h k

& - oT =

eC) = gd nT +h nag in . = # w fF

g .

ha =

u £ LL 5 %

AFR B3 98 18:3p :

PA ADE Aa a

are oc IMNd 43d =a30 dodge dd 22:8 280 28 ddd

#ok PE T0Hd THIOL ok 06d THIOL Hk rrr STEN ALAS ANS Esau ssf)

g

1

¥

%

£

:

+ oF ;

: of id 28 insar

A : v oe

Fi] be 2 LE 130 ENAnuYar 1 or ar =

=» = -~

# J gi E C TAR TAT i i

= - =

ALY. EF = os em

BUSAN IAg la; did be BRS Nel 4 RE

|

. 4 =~}

§

Y ol od

1 =

w il

i : fA

{ L

| £ of 5 2 abl E21 ¥ a 2

|

# e L po “A = w= al

% . a £ Be 2

wr iy Y p& = E

_— = 3

3 L E

& 1 4 yw - | a

_

:

3 8 on a By x . d } Ai BEEN TE Memoranda with rafay i

a8 SCOR AF ReIsibhia 4 .

E> 4 N 3 a1 A bE Wa SL * .

4

1

ol or =

ef ¥ # :

ry’

|

ey ad

SY m ,

|

“tates

i

3

| |

i

a

a

.

.

.

—-

e

APR 83 '95 18:3p

SETTSEECLETE OL 2654 982 2

7-430

. "

“%

ah

' HN

dad - 5 -

Bay

. oo

°F -

Pletricr Oli

+ PALE RAZR A

P.02/02

EE BIZ n= 5 "HE 0 He BEE

a

[)

F-173

™ -

26 EE Hdd