Conley v. Gibson Petitioner's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Conley v. Gibson Petitioner's Brief, 1957. 4e5e7f1d-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8ef34ef0-b376-47ea-94ea-06a80d017457/conley-v-gibson-petitioners-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

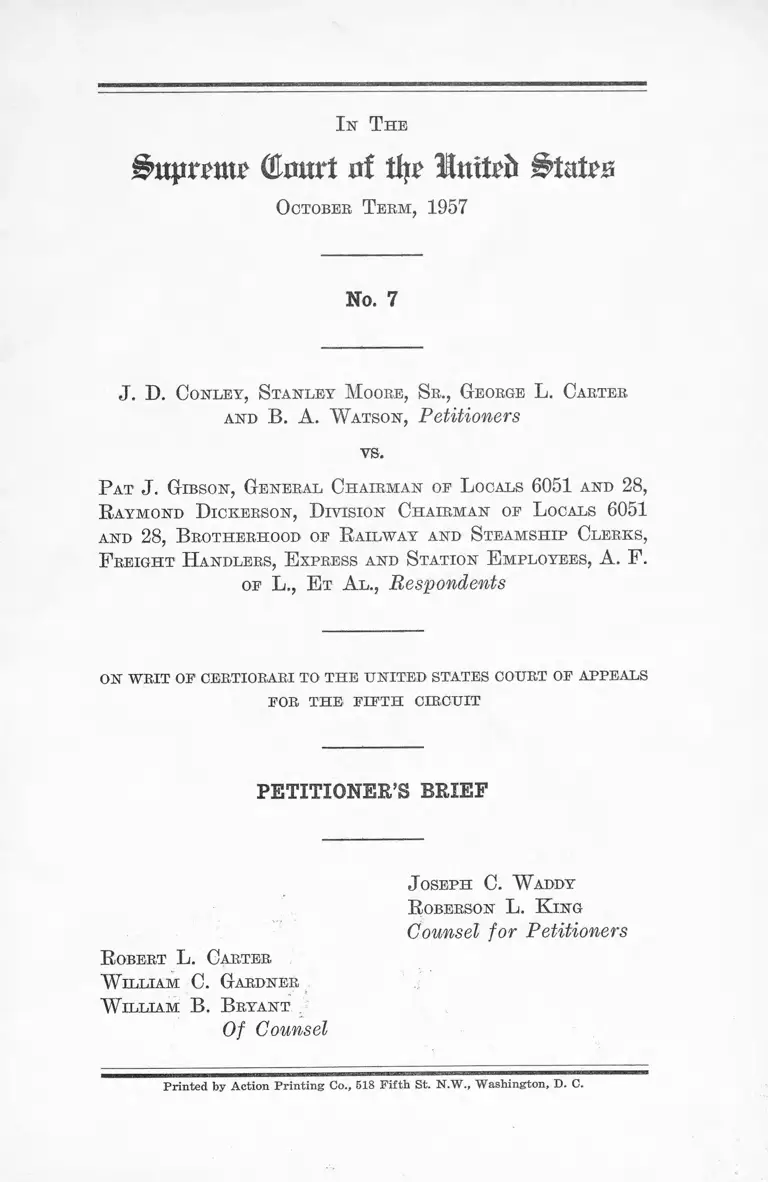

In The

(tart rtf tljr Ituiti'ii BtuUs

October T erm , 1957

No. 7

J. D. Conley, Stanley M oore, Sr., George L. Carter

and B. A. W atson, Petitioners

vs.

P at J. Gibson, General Chairman op L ocals 6051 and 28,

R aymond D ickerson, D ivision Chairman op L ocals 6051

and 28, B rotherhood of R ailway and Steamship Clerks,

F reight H andlers, E xpress and Station E mployees, A. F.

op L., E t A l ., Respondents

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

PETITIONER’S BRIEF

J oseph C. W addy

R oberson L. K ing

Counsel for Petitioners

R obert L. Carter

W illiam C. Gardner

W illiam B. B ryant

Of Counsel

Printed by Action Printing Co., 518 Fifth St. N.W., Washington, D. C.

INDEX

Page

OPINIONS B E L O W ___ _____________________________ 1

JURISDICTION_____________________________________ 2

STATUTES INVOLVED___________________________ _ 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED _________________ 3

STATEMENT OP THE C A SE _______________________ 4

SUMMARY OP ARGUMENT________________________ 6

ARGUMENT ________________________________________ 7

I. The Complaint Charges the Brotherhood With

Breach of the Duty of Fair Representation Im

posed Upon It by the Railway Labor Act and

With Abuse of Statutory Position and Power

and, Therefore, Is Within the Jurisdiction of

the Court____________________________________ 7

II. There Are No Factors Present in This Case

Either Ousting or Limiting the Jurisdiction

of the Court_________________________________ 13

CONCLUSION ______________________________________ 17

TABLE OF CASES

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen v.

Mitchell, 190 F. 2d 308 (1951)____________________ 9

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U.S.

768, 96 L.Ed. 1293 (1953)___________________8, 9,13,16

Central of Georgia Railway Co. v. Jones, 229 F. 2d 648

(1956) _________________________________________ 9

Dillard v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 199 F. 2d 948

(1952) _________________________________________ 9,13

Georgia v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 324 U.S., 89 L.Ed 105

(1945) _________________________________________ 16

Graham v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and

Enginemen, 330 U.S. 232, 94 L.Ed 23 (1949)_______8,13

Page

Great Northern R. Co. v. Merchants Elevator Co., 259

U.S. 285, 66 L.Ed 943 (1922)_____________________ 16

Hayes v. Union Pacific Railroad Co., 184 F. 2d 337, cert.

den. 340 U.S. 942 (1951)_________________________ 13

Hettenbangh v. Air Line Pilots Association, 189 F. 2d

319 (1951) ______________________________________ 6,13

J. I. Case Co. v. National Labor Relations Bd., 321 U.S.

332 88 L.Ed. 762 (1944)_________________________ 11

Richardson, et al., v. Texas & New Orleans R. Co., et al.,

242 F. 2d 230 (1957)______________________________ 9

Rolax, et al., v. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co., et al.,

186 F. 2d 473 (1951)____ 9

Slocum v. Delaware, L. & W. R, Co., 339 U.S. 239, 94

L.Ed. 795 (1950)_________________________________ 6,14

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., et ah, 323 U.S.

192, 89 L.Ed. 173 (1944)_________ 7,8,11,12,13,15,16

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210, 89 L.Ed. 187 (1944)____8,11,13

Constitution

Fifth Amendment___________________________________ 6

Statutes

Railway Labor Act, 48 Stat. 1185, 45 U.S.C., Sec. 151

et seq.____________________________ ______________ 2,10

In The

(tart of thr Inttrfr BtaUB

October T erm , 1957

No. 7

J. D. Conley, Stanley M oore, Sr., George L. Carter

and B. A . W atson, Petitioners

vs.

P at .J. G ibson, General Chairman oe L ocals 6051 and 28,

R aymond D ickerson, D ivision Chairman oe L ocals 6051

and 28, B rotherhood of R ailway and Steamship Clerks,

F reight H andlers, E xpress and Station E mployees, A . F.

oe L., E t A l ., Respondents

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

PETITIONER’S BRIEF

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Texas was filed March 16, 1955,

and appears on page 19 of the Transcript of Record.

2

The per curiam opinion of the United States Court, of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is officially reported in 229

F. 2d 436, and is printed in the Transcript of Record at

page 29a.

A petition for rehearing was denied without opinion by

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

on March 15, 1956 (R. 30).

Jurisdiction

The Judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit was entered January 31, 1956. Re

hearing was denied March 15, 1956.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section

1254(1) of Title 28 of the United States Code.

Statutes Involved

The Statute involved is the Railway Labor Act as

amended, 45 United States Code, Section 151, et seq., and

particularly the following:

Section 152:

“ Fourth. Employees shall have the right to organ

ize and bargain collectively through representatives

of their own choosing. The majority of any craft or

class of employees shall have the right to determine who

shall be the representative of the craft or class for the

purposes of this chapter. . . . ”

“ Eleventh. Notwithstanding any other provisions of

this chapter, or of any other statute or law of the

United States, or Territory thereof, or of any State,

any carrier or carriers as defined in this chapter and

a labor organization or labor organizations duly desig

nated and authorized to represent employees in ac

cordance with the requirements of this chapter shall

be permitted—•

(a) to make agreements, requiring, as a condition of

continued employment, that within sixty days following

the beginning of such employment, or the effective date

of such agreements, whichever is the later, all em

ployees shall become members of the labor organization

3

representing their craft or class: Provided, That no

such agreement shall require such condition of employ

ment with respect to employees to whom membership

is not available upon the same terms and conditions as

are generally applicable to any other member. . . . ”

Section 153:

“ First (i). The disputes between an employee or

group of employees and a carrier or carriers growing

out of grievances or out of the interpretation or ap

plication of agreements concerning rates of pay, rules,

or working conditions, including cases pending and

unadjusted on June 21, 1934, shall be handled in the

usual manner up to and including the Chief Operating

Officer of the carrier designated to handle such dis

putes ; but, failing to reach an adjustment in this man

ner, the disputes may be referred by petition of the

parties or by either party to the appropriate division

of the Adjustment Board with a full statement of the

facts and all supporting data bearing upon the dis

putes. ’ ’

Questions Presented

Whether a complaint by Negro members of a craft of

railway employees against a labor union—their collective

bargaining representative under the Railway Labor Act—

alleging that, solely because of their race, the union bars

them from membership in its local lodge which carries on

the collective bargaining process; uses its statutory position

to compel them to maintain membership in an inferior,

racially segregated local; refuses to exert any effort toward

maintenance of the collective agreement insofar as it per

tains to the Negro members of the craft, resulting in their

loss of employment and employment rights; and refuses

either to hear their charges of discrimination or to take

any steps to investigate and redress their wrongs, states

a claim against the bargaining representative within the

jurisdiction of the Federal courts for breach of the statu

tory duty of fair representation imposed upon such repre

4

sentative by the Railway Labor Act, notwithstanding the

fact that the complaint makes no claim either that the col

lective agreement was unlawfully entered into or is un

lawful in its terms or effect?

(a) If jurisdiction exists, is there present in this case

any factor either ousting or limiting that jurisdiction?

Statement of the Case

Petitioners, employees of the Texas and New Orleans

Railroad Company in its Freight House at Houston, Texas,

are Negroes and are members of the craft or class of clerks,

freight handlers, express and station employees of that

company. (R. 7). The craft is composed of both white and

colored employees and is represented for collective bargain

ing purposes under the Railway Labor Act by the Brother

hood of Railway and Steamship Clerks, Freight Handlers,

Express and Station Employees (hereinafter called the

Brotherhood). (R. 7, 8). There is an agreement, enacted

pursuant to Section 2—Eleventh of the Railway Labor Act,

45 U.S.C.A. 152—Eleventh, (commonly known as a “ union

shop agreement” ), in effect between the Brotherhood and

the carrier, requiring all members of the craft or class, as

a condition of continued employment, to become members

of the Brotherhood. (R. 10). The Brotherhood maintains

two local lodges at Houston for the members of the craft

—Local 28, composed exclusively of white employees, and

Local 6051, composed exclusively of Negro employees.

Petitioners and those they represent are barred from mem

bership in Local 28, and are forced to maintain membership

in Local 6051. (R. 9, 10). The Brotherhood carries on its

collective bargaining with the carrier through Local 28.

(R. 9, 10).

On August 21, 1954, petitioners brought a class suit in

the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Texas, on behalf of themselves and others similarly situ

ated, against the Brotherhood, two of its officials and Local

28, in which they charged that- Local 6051, which the

5

Negro members of the craft are compelled to join, is a

segregated, inferior unit of the Brotherhood, maintained

solely for the purpose of affording petitioners and those

similarly situated representation inferior to and different

from that afforded white members of the craft in Local 28

(R. 9, 10); and also that the Brotherhood has refused to

afford petitioners and the other Negroes similarly situated

representation and protection equal to that afforded those

members of the craft who are white (R. 10, 13). The rail

road company, their employer, was not made a party to the

suit.

Petitioners complained that on or about May 1, 1954,

their employer posted a notice at the Freight House al

legedly abolishing 45 jobs; that all of these jobs were being-

held by Negro members of the craft; that no advance notice

of the abolition of the jobs was given to petitioners and

those similarly situated as required by the collective bar

gaining agreement (R. 11); that said jobs were not in fact

abolished, for immediately thereafter many white persons

were hired to perform the same work, and subsequently,

some of the same Negro employees who had been previously

fired were rehired, but without seniority, and junior to the

recently hired white employees (R. 12); and that none of

the white members of the craft were discharged or dis

placed (R. 13). Petitioners further charged in their com

plaint that the Brotherhood suffered and permitted their

jobs to be abolished because of their race and also that

the Brotherhood repeatedly refused to grant petitioners

a hearing concerning their discharge and declined to come

to their aid (R. 11, 12). They alleged that the acts and

omissions of the Brotherhood, complained of in this case,

constituted a planned course of conduct designed to dis

criminate against petitioners and those similarly situated,

solely because of their race or color, and that by reason of

said acts and in refusing to represent them and to give

them protection equal to that afforded the white members of

the craft, the Brotherhood breached the statutory duty im

6

posed upon it by the Railway Labor Act to represent all

members of the craft fairly and impartially (R. 13). They

further alleged that, by reason of this conduct by the

Brotherhood, petitioners and those similarly situated have

been deprived of rights and property without due process

of law in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. They prayed for a declaratory judg

ment, injunctive relief and damages.

The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on four

grounds: (1) lack of jurisdiction of the subject matter;

(2) lack of an indispensable party defendant—the railroad

company; (3) failure to present a justiciable issue, and (4)

failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

The District Court dismissed the complaint for lack of

jurisdiction of the subject matter. On appeal by petitioners

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

that Court, without discussion, affirmed, in a per curiam

opinion, citing Slocum vs. Delaware, L. & W. R. Co., 339

U. S. 239, and Hettenbaugh v. Air Line Pilots Association,

189 F. 2d 319. A petition for rehearing was denied without

opinion.

Summary of Argument

The cause of action stated in the complaint is one over

which Federal Courts have jurisdiction because it charges

the Brotherhood with breach of the statutory duty of fair

representation it owed to petitioners as members of a craft

of railway employees for which that Brotherhood was the

exclusive representative, and with unlawful abuse of statu

tory position and power. The Brotherhood violated its duty

and abused its statutory powers by compelling petitioners,

solely on account of their race, to maintain membership in

an inferior, ineffective, segregated local of the union, cut off

from the local that carried on the collective bargaining, and

then refusing to hear the complaints or to take any steps

within the collective bargaining process to enforce the rights

of petitioners, thus denying to them the benefits and ad

7

vantages of collective bargaining. The duty imposed on

the bargaining representative by the Railway Labor Act to

represent all members of the craft fairly is not limited to

the making of a contract but is coextensive with the total

authority and power given the representative by the statute.

A refusal by the Brotherhood to represent members of the

craft, solely on account of race, in any portion of the collec

tive bargaining process is a breach of that duty.

Neither the provisions of the Railway Labor Act nor

the doctrine of primary jurisdiction precludes the court

from exercising jurisdiction in this action by Negro mem

bers of a craft of railway employees, charging their bar

gaining representative with violation of statutory duty and

unlawful abuse of power because (1) such a dispute has not

been relegated by the statute to the administrative tribunals

created by the Act; (a) the dispute does not involve the

interpretation or application of the collective bargaining

agreement; (b) the provision of the statute creating the

National Railroad Adjustment Board makes no reference

to disputes between employees and their representative;

(2) No administrative expertise or specialized skill is

needed to determine the existence or non-existence of racial

discrimination by the bargaining representative in this case,

and (3) even if the Adjustment Board had the power to act

in this case, it would not constitute an adequate administra

tive remedy because the very Brotherhood against whom

petitioners complain sits as judge on that Board.

ARGUMENT

I. The Complaint Charges The Brotherhood W ith Breach

of the Duty of Fair Representation Imposed Upon It By The

Railway Labor Act And With Unlawful Abuse of Statutory

Position and Power and, Therefore, Is Within The Juris

diction of the Court

In 1944 this Court, in the case of Steele v. Louisville &

Nashville R. Co., et al., 323 U. S. 192, 89 L. Ed. 173, held

8

that the bargaining representative of a craft of railway

employees is under a duty imposed by the Railway Labor

Act to represent all members of the craft for which it acts,

fairly, impartially and without hostile discrimination, and

stated that:

“ So long as a labor union assumes to act as the

statutory bargaining representative of a craft, it cannot

rightly refuse to perform the duty, which is inseparable

from the power of representation conferred upon it,

to represent the entire membership of the craft.” (323

U. S. 192, 204).

This Court held also that a complaint alleging a breach

by the collective bargaining representative of that statu

tory duty states a claim upon which courts have jurisdic

tion to grant relief and that:

“ . . . the statute contemplates resort to the usual

judicial remedies of injunction and award of damages

when appropriate for breach of that duty.” (323 IT. S.

192, 207).

In a companion case decided on the same day as Steele,

this Court held that Federal Courts have jurisdiction of

the subject matter of a complaint charging the bargaining

representative with breach of the statutory duty of fair

representation.

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210, 89 L. Ed. 187 (1944).

The principles of the Steele and Tunstall cases were re

affirmed by this Court in Graham v. Brotherhood of Loco

motive Firemen & Enginemen, 338 U. S. 232, 94 L. Ed. 23

(1949), and were re-affirmed and extended in Brotherhood

of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U. S. 768, 96 L. Ed.

1293 (1952), where this Court held that the Railway Labor

Act prohibits bargaining agents it authorizes from using

their position and power to destroy colored workers’ jobs

in order to bestow them on white workers and stated that:

9

“ Bargaining agents who enjoy the advantages of the

Railway Labor A ct’s provisions must execute their

trust without lawless invasions of the rights of other

workers.” (343 IT. S. 768, 774).

These principles have been followed by the United States

Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Rolax,

et al. v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., et al., 186 F. 2d 473

(1951), and Dillard v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 199 F. 2d

948 (1952), and by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen

and Enginemen v. Mitchell, 190 F. 2d 308 (1951), Central of

Georgia Railway Co. v. Jones, 229 F. 2d 648 (1956), and in

Richardson, et al. v. Texas (& New Orleans R. Co., et al.,

242 F. 2d 230 (1957).

From the above cited cases it is clear that jurisdiction

of courts, both State and Federal, to hear and determine

suits brought by members of a craft of railroad employees

against their statutory collective bargaining representative,

to redress wrongs resulting from unfair representation and

to obtain relief from racially discriminatory practices and

contracts, is no longer a subject for debate. Nevertheless,

in the instant case, the courts below refused to apply these

established principles because of the absence of any allega

tion in the complaint that the collective agreement was un

lawful in itself. This action by the courts below pre-sup-

poses the existence of a doctrine of law to the effect that

the right of members of a craft of railway employees to fair

representation by their collective bargaining representa

tive under the Railway Labor Act is judicially enforceable

only when the collective bargaining agreements are unlaw

fully entered into, or when the agreements themselves are

unlawful in terms or effect. Petitioners respectfully urge

that the doctrine espoused by the lower courts is unsound

in principle; subverts the intention of Congress in enacting

the Railway Labor Act and is in the teeth of the pronounce

ments of this Court.

10

It is unsound in principle because the exclusion from

judicial enforcement of all rights to fair representation

except those incident to contract making leaves the statu

tory bargaining representative with unbridled power to

otherwise discriminate with impunity against members of

the craft and free to otherwise use its statutory position and

power in a lawless and arbitrary manner, to the detriment

of the minority members of the craft for which it is au

thorized to act.

In enacting the Railway Labor Act to provide for the

peaceful maintenance of agreements and settlement of dis

putes between employer and employee through a continu

ous process of collective bargaining, Congress saw fit to

provide for an exclusive bargaining representative, to be

chosen by the majority of the craft, and to vest that repre

sentative with the power of complete control of all craft

activities and incidents and to legislate for and bind the

individual and minority members of the craft even against

their will. To protect the individual and minority members

from abuse of this statutory power it imposed upon that

representative the duty to represent all members of the

craft. Clearly, it did not intend to limit this duty or to

restrict the right to only one phase of the total authority

and power granted. On the contrary, it must be assumed

that Congress intended to make that duty coextensive with

the total authority and power given the representative by

the Act. Otherwise, the Act would bear the condemnation

of unconstitutionality under the Fifth Amendment.

Petitioners’ contentions in this respect are buttressed

further by the legislative history of the Union Shop Amend

ment to the Act (45 U. S. C., Section 152, Eleventh). This

amendment increased the power of the representative over

the individual employee by making it lawful for the repre

sentative to make an agreement with the carrier requiring

that, as a condition of continued employment, all members

of the craft must join the union. However, in reporting

this legislation to the floor of the Senate the Committee

11

was careful to make it clear that the grant of authority

carried with it the duty to represent. The Committee stated

in its report:

“ Your committee also desires to make it clear that

nothing in this bill is intended to modify in any way

the requirement that the authorized bargaining repre

sentative shall represent all the employees in the

craft or class, including non-union employees as well

as members of the union, fairly, equitably, and in good

faith. ( See Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad

Co., 323 U. S. 192, and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Loco

motive Firemen and Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210).’ ’ (Sen

ate Report No. 2263, 81st Congress, 2d Session).

The making of a collective bargaining agreement does

not complete the collective bargaining process nor exhaust

the statutory power of the representative. There is the

continuing process of day to day adjustments and periodic

discussions concerning such matters as shop rules, job con

tent, and work assignments. These matters, vital to the

employment of every member of the craft, have been placed

by the Railway Labor Act in the hands of an exclusive

bargaining representative. To the extent that the repre

sentative participates in this process, it exercises a power

which is conferred, defined, regulated and protected by the

statute. This Court pointed out in J. I. Case Co. v. National

Labor Relations Bd., 321 IT. S. 332, 88 L. Ed. 762 (1944)

that:

“ The very purpose of providing by statute for the

collective agreement is to supersede the terms of sepa

rate agreements of employees with terms which reflect

the strength and bargaining power and serve the wel

fare of the group. Its benefits and advantages are open

to every employee of the represented unit.” (321 U. S.

332, 338);

and in Steele, supra:

“ The purpose of providing for a representative is

to secure those benefits for those who are represented

and not to deprive them or any of them of the benefits

of collective bargaining for the advantage of the repre

12

sentative or those members of the craft who selected

it.” (323 IT. S. 192, 201). (Italics ours.)

Thus, a refusal by the bargaining representative to exer

cise these non-contract making collective bargaining powers

on behalf of Negro members of the craft, solely on account

of their race, is a refusal by it to represent all members of

the craft, depriving the Negroes of the benefits and ad

vantages of collective bargaining, and constitutes the crea

tion of distinctions within the craft based on race alone.

This Court held in the Steele case, supra, that distinctions

based on race alone are “ obviously irrelevant and invidi

ous” and that “ Congress plainly did not undertake to au

thorize the bargaining representative to make such dis

criminations.” (323 IT. S. 192, 203).

The complaint in this case alleges that the Brotherhood

used the power conferred upon it by the statute to compel

petitioners and the other Negro employees to join and

maintain membership in the union. However, it barred

them from membership in that local which carries on the

collective bargaining for the craft and forced them into an

inferior, segregated local, and refused to hear or consider

the complaints of the Negroes concerning their welfare as

members of the craft. It made an agreement with the car

rier covering the craft and then arbitrarily refused to take

any steps within the collective bargaining process to en

force the rights of Negro employees covered by that con

tract. Thus, on the one hand, it abuses its statutory powers

and, on the other, it abnegates its statutory duty. Its con

duct was a denial to the Negro members of the craft those

benefits and advantages of collective bargaining which this

Court has held must be open to every member of the repre

sented unit. Here is a clear case of a bargaining representa

tive using Federal statutory power, solely for its own

benefit, by compelling the Negro members of the craft to

pay hard-earned money into its coffers and then refusing

to represent them within the collective bargaining process.

Such conduct on the part of the bargaining representative

13

subverts the purpose of the Railway Labor Act; is un

mistakably a refusal on the part of the Brotherhood to

represent all members of the craft fairly, and constitutes

an unlawful abuse of statutory powers, which under the

principles enunciated by this Court in Steele, supra, Tuns

tall, supra, Graham, supra, and Howard, supra, and by the

Fourth Circuit in Dillard v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad

Co., supra, courts have jurisdiction to correct and restrain.

It is respectfully submitted that the Courts below erred

in refusing to apply the principles of the above-mentioned

cases and that, to the extent that Hettenbaugh v. Air Line

Pilots Association, 189 F. 2d 319 (1951), and Hayes v. Union

Pacific Railroad Co., 184 F. 2d 337, cert. den. 340 U.S. 942,

(1951) (cited and relied upon by the courts below in support

of their position) may be in conflict with those principles,

they are unsound and do not accurately state the law.

II. There Are No Factors Present In This Case Either

Ousting or Limiting The Jurisdiction of The Court

As has been shown above, when the complaint in this case

is tested by the well settled principles of law applicable to

rights and duties arising under the Railway Labor Act, it

is immediately apparent that this case falls within the gen

eral jurisdiction of Federal Courts. Unless there is present

some factor either ousting or limiting that jurisdiction, the

justiciability of the cause is beyond question.

The courts below held that the quasi-judicial tribunals

established by the Railway Labor Act preclude the courts

from exercising jurisdiction. This holding was predicated

upon the view that the case was one involving the breach of

performance of a collective bargaining agreement. Peti

tioners contend that this view is erroneous and that the case

alleged must be looked upon as one involving a breach of

the statutory duty imposed upon the Brotherhood by the

Railway Labor Act.

14

This complaint does not involve a dispute between, an em

ployee or group of employees on the one hand, and a carrier

or carriers on the other. The railroad company is not even

a party to the suit. Although petitioners may have concur

rently a claim against their employer for violation of the

collective agreement, that claim is not asserted in this case.

The dispute petitioners seek to have adjudicated is en

tirely between them and their statutory representative.

The rights here sought to be enforced do not stem from any

contract between the carrier and the representative, but di

rectly from the statute, and may be adjudicated without in

any manner considering whether there was or was not, in

fact, a breach of the collective agreement by the carrier.

What must be considered and determined is whether there

was a breach by the Brotherhood of the statutory duties im

posed upon it to represent all members of the craft fairly

and to refrain from using its statutory position and power

to discriminate against the Negro members of the craft.

When viewed in this, its true light, it becomes obvious

that the dispute here is not one that Congress relegated for

adjudication to the administrative tribunals created by the

Railway Labor Act but is one that was left to the jurisdic

tion of the courts. It also becomes obvious that the courts

below erroneously applied the doctrine of the Slocum case

(.Slocum v. Delaware, L. & W., 339 U.S. 239, 94 L. Ed. 795

(1950)).

In that case, two unions were vying with each other over

certain jobs—each claiming the jobs for its members under

its respective collective bargaining agreement. The railroad

company was caught in the vise and it brought an action in

a New York State court against both unions for a declara

tory judgment and prayed for an interpretation of both

agreements. This Court held that disputes between carriers

and their employees involving the interpretation of collec

tive bargaining agreements fell within the exclusive juris

diction of the National Railroad Adjustment Board created

by the Railway Labor Act.

15

There is no parallel in the facts alleged in this case to

those involved in the Slocum case, supra. Here, the suit is

brought by individual members of the craft against their

collective bargaining representative alone, seeking enforce

ment of statutory rights especially designed for their pro

tection and welfare. Those rights inhere in the relation

ship of craft member—craft representative created by the

statute and are in no way dependent upon the interpreta

tion of the collective agreement.

Furthermore, no administrative procedure was created

by the Railway Labor Act for the determination of disputes

between the employee and his statutory bargaining repre

sentative. This Court stated in Steele, supra, that:

“ Section 3, First (i), which provides for reference to

the Adjustment Board of disputes between an employee

or group of employees and a carrier or carriers growing

out of grievances or out of the interpretation or appli

cation of agreements’ makes no reference to disputes

between employees and their representative.” 323 TT.S.

192, 205. (Italics ours.)

Since the dispute in this case is between members of the

craft and their statutory representative, courts must exer

cise jurisdiction or leave the members of the craft without

remedy. The rights to fair representation and freedom from

unlawful abuse of statutory power would be sacrificed and

obliterated if courts were without power to redress for vio

lations of those rights.

Petitioners urge also that the doctrine of primary juris

diction is no bar to the exercise of jurisdiction by the court.

This Court has limited this doctrine of prior resort so as to

make its applicability dependent upon (1) the nature of the

question presented and (2) adequacy of the administrative

remedy. Thus it would seem that only those questions which

require the skill of administrative specialists and the exer

cise of specialized judgment should be placed beyond tradi

tional judicial scrutiny and relegated for initial determina

tion to an administrative agency.

16

Great Northern R. Co. v. Merchants Elevator Co., 259

U.S. 285, 66 L.Ecl. 943 (1922).

And where the administrative remedy is inadequate, or the

failure of the court to exercise jurisdiction would result in

a sacrifice or obliteration of the right involved, prior resort

to the administrative agency will not be required.

Georgia v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 324 U.S. 439, 89 L. Ed.

105 (1945).

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., supra.

Inasmuch as an interpretation of the collective agreement

is neither necessary nor required in this case, no adminis

trative expertise nor specialized skill and judgment is

needed for a determination of the issues involved. As has

been pointed out, the Railway Labor Act has not placed

jurisdiction in the National Railroad Adjustment Board of

disputes between employees and their representative. Fur

thermore, the Brotherhood has its own representative on the

Adjustment Board. That representative is paid by the

Brotherhood and has no fixed term of employment, but is

recallable at the will of the Brotherhood. Thus to require

petitioners to submit their case to the Adjustment Board

would be to compel them to have their rights adjudicated

by the very same persons who are destroying them. More

over, this Court has already held that where a collective

bargaining representative engages in hostile discrimination

against Negro members of a craft, those discriminated

against are without adequate administrative remedy, and

prior resort to the agencies created by the statute is not

required.

Steele v. L. & N. R. Co., supra.

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, supra.

Petitioners conclude, therefore, as this Court did in Steele,

supra:

“ In the absence of any available administrative rem

edy, the right here asserted, to a remedy for breach of

17

the statutory duty of the bargaining representative to

represent and act for the members of a craft, is of judi

cial cognizance. That right would be sacrificed or oblit

erated if it were without the remedy which courts can

give for breach of such a duty or obligation and which

is their duty to give in cases in which they have juris

diction. . . For the present command there is no mode

of enforcement other than resort to the courts, whose

jurisdiction and duty to afford a remedy for a breach

of statutory duty are left unaffected.” (323 U.S. 192,

207). (Italics ours).

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that this complaint, charging

abuse of Federal statutory power and disregard of statutory

obligation by the Brotherhood and the use by it of its posi

tion to discriminate against Negro members of the craft,

solely because of their race, is of judicial cognizance, and

that the courts below erred in dismissing for lack of juris

diction of the subject matter.

Respectfully submitted,

J oseph C. W addy

R oberson L. K ing

Counsel for Petitioners

R obert L. Carter

W illiam C. Gardner

W illiam B. B ryant

Of Counsel