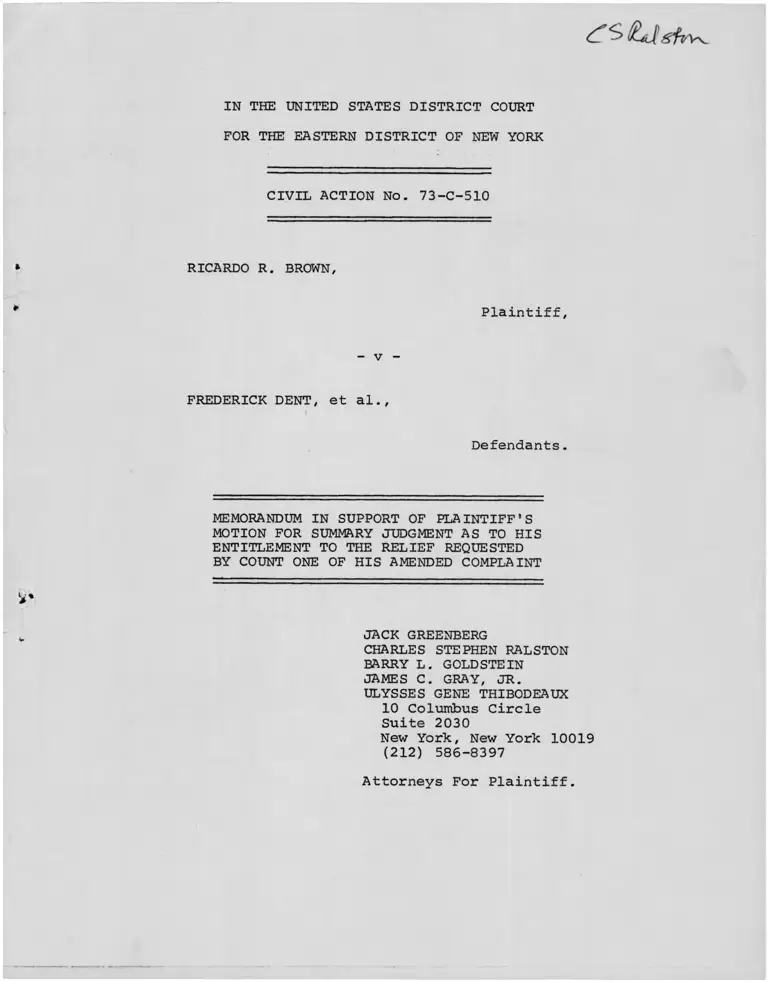

Brown v Dent Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment

Public Court Documents

June 8, 1976

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v Dent Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment, 1976. 20ae19ee-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8f14a5b2-4c78-41e0-85f1-28d185f5770d/brown-v-dent-memorandum-in-support-of-plaintiffs-motion-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

CIVIL ACTION No. 73-C-510

RICARDO R. BROWN,

Plaintiff,

- v -

FREDERICK DENT, et al..

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AS TO HIS

ENTITLEMENT TO THE RELIEF REQUESTED

BY COUNT ONE OF HIS AMENDED COMPLAINT

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

JAMES C. GRAY, JR.

ULYSSES GENE THIBODEAUX

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys For Plaintiff.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

RICARDO R. BROWN,

Plaintiff, :

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 73-C-510

Defendants.

-against-

FREDERICK DENT, et al.,

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF'S

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AS TO HIS

ENTITLEMENT TO THE RELIEF REQUESTED

BY COUNT ONE OF HIS AMENDED COMPLAINT

I.

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiff Ricardo R. Brown served at the United States

Merchant Marine Academy for two years as an instructor-trainee

in the Academy's Department of Physical Education and Athletics.

The Instructor-Trainee program in which he participated was part

of the Academy's affirmative action program and was designed to

give minority and women candidates Academy-level teaching ex

perience and the necessary training required to serve as Instructor

at the Academy or a similar institution. During his second year,

Mr. Brown applied on two occasions for a regular faculty appoint

ment when vacancies arose in his department and on both occasions

a white person from outside of the Academy was hired to fill the

position. Mr. Brown is black. Towards the end of his appointment

Mr. Brown requested a temporary appointment which would allow him to

continue to serve through the end of the academic year. This re

quest was also denied.

In January 1973, when his appointment ended, Mr. Brown

filed a formal complaint of racial discrimination against the

Academy with the Department of Commerce. Pursuant to the 1972

amendments to Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§2000-e, and the regulations promulgated by the United States Civil

Service Commission under that Title, Mr. Brown sought relief through

the requisite administrative process. He met with an investigator

and presented a written statement of events surrounding his charges,

including relevant documentation.

In April 1973, plaintiff through his counsel initiated

the current action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1981 and served interro

gatories on defendants. As the court may recall, a stay of pro

ceedings in this suit was agreed to by respective counsel in light

of the ongoing administrative process. Defendants did provide

answers to the interrogatories which were served on them.

In May 1973, an investigator's report was presented to the

Maritime Administration and by a letter dated May 29, 1973, the

Academy's Equal Employment Opportunity Officer, Captain Renick,

wrote Mr. Brown telling him of the proposed disposition of his

complaint; no relief was offered. Plaintiff requested a hearing

before a Civil Service Appeals Examiner and a hearing was held on

February 20-21, 1974 before the Honorable Robert J. Shields. A

2

transcript of the two-day hearing was prepared (Exhibit "E" to the

Amended Complaint). By a letter dated April 22, 1974, the Depart

ment of Commerce informed plaintiff of their decision which adopted

in toto the Examiner's "Findings and Recommended Decision"(Exhibits

"A" and "B" to the Amended Complaint). In sum, the Department of

Commerce determined that discrimination on the basis of race had

occurred and had affected plaintiff's employment opportunities

and recommended that he be appointed to the next vacancy in the

Department.

Counsel for plaintiff filed a Notice of Partial Appeal

on May 8, 1974, to the Civil Service Commission challenging the

adequacy of the relief offered in that the only thing plaintiff

received was a promise, at best, of future employment at some

indefinite, hypothetical future time (Exhibit "C" to the Amended

Complaint). Specifically, plaintiff sought (1) an offer of

immediate appointment to a vacancy in the Department which had

arisen since plaintiff's departure and which had not been filled,

facts which were brought out at the hearing; (2) back pay for

income lost; (3) equitable contract and tenure terms; and (4)

reasonable attorneys' fees. The clear effect of the Department

of Commerce decison was that plaintiff had won but won nothing,

while the Academy had lost but lost nothing. The remedy was

totally inadequate.

In November 1974, the United States Civil Service Com

mission's Appeals and Review Board affirmed the Department of

Commerce's decision (Exhibit "D" to the Amended Complaint). The

Commission, thus, denied plaintiff any further relief beyond that

3

given by the Department of Commerce which was tantamount to no

relief at all.

Plaintiff therefore amended his complaint in December

1975 to reflect the completion of the administrative process

under Title VII and to seek from this Court the relief wrongfully

denied him by the Department of Commerce and the Civil Service

Commission. In addition, he amended his complaint to include a

second count naming the Commission and its members as additional

Parties defendant. Count Two is a class action on behalf of all

federal employees who seek relief from alleged discriminatory

acts by federal agencies and prays for additional declaratory and

injunctive relief which would require defendants to properly

implement Title VII by correctly applying the law as developed

by providing corrective relief to successful complainants at the

administrative level.

The instant motion for Summary Judgment is directed

towards Court One of the Amended Complaint relating to plaintiff's

entitlement to remedial relief which would help to make him whole.

While Count Two is not directly addressed herein, several of the

discussions of applicable Title VII law may be instructive on the

Commission's misapplication of Title VII.

4

II.

PLAINTIFF HAVING PROVEN DISCRIMINATION

AT THE ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL AND BY THE

FACTS IS ENTITLED TO SUMMARY JUDGMENT

ON THE ISSUE OF DISCRIMINATION.________

As a result of the administrative record, the Depart

ment of Commerce adopted the Examiner's finding that:

... There is evidence, however, that the Academy

and its administrators employed various vehicles

of discrimination and further, that they failed

to take action which was required of them under

Presidential mandate. For these reasons we must

conclude that there was in fact discrimination in

connection with the failure to appoint Ricardo R.

Brown to a position on the Kings Point faculty.

(Exhibit "A", p.2)(emphasis added)

This admission of discrimination should be conclusive on the

issue of discrimination. Findings of discrimination by a

federal agency are extremely rare since the agencies have an

interest in not finding discrimination.

The facts of this case clearly show the correctness

of the Department of Commerce's determination of discrimination.

A review of the Academy's treatment of plaintiff's three applica

tions for appointment, especially when viewed against the Academy's

employment record with regard to black faculty, leads to the in

escapable conclusion that racial discrimination occurred and

that plaintiff was denied equal employment opportunity.

Under these circumstances, plaintiff is entitled to

summary judgment on the issue of discrimination: as a matter of

law, defendants by their acts of commission and omission have

violated plaintiff's rights and Title VII.

5

A . The Department of Commerce Has Admitted that

Discrimination Occurred in the Academy's Treatment

of Plaintiff's Efforts to Obtain a Faculty Appointment

The Assistant Secretary for Administration for the

Department of Commerce stated in his letter to plaintiff of

April 22, 1974, notifying him of the agency's final decision, that

It is my decision that your allegation of

discrimination because of race is supported

by the evidence of the record, (Exhibit "A", p.2^.

The Assistant Secretary also adopted in. toto the

Examiner's Findings and Recommended Decision which in pertinent

parts stated the following (references are to page numbers in

Exhibit "B" the Examiner's Report):

The testimony at the hearing and the report

of investigation sets forth one fact quite

clearly, Mr. Brown's services as a Teaching

Fellow at the Academy were satisfactory or

better.

In the course of his two years at the Academy

he definitely demonstrated his ability to

handle the position as an instructor of

Physical Education, [p.4-5]

We found in the course of the hearing and as

the result of information contained in the

investigative report that there were numerous

occasions upon which the Academy bent the re

gulations or obtained waivers for certain in

dividuals in order to place them on the

faculty in positions for which they did not

qualify under the terms of the Academy's own

standards, [p.5]

The United States Merchant Marine Academy at

Kings Point, New York had an affirmative

action program whose sole purpose was to

place Blacks and other minorities on the

faculty, since 1968. As of the date of the

hearing there are no Black members on the

Kings Point faculty [p.6](emphasis added)

A Mr. Kenneth Bantum, a Black was a member of

the faculty for three years. He left the

6

faculty when, despite the unanimous recom

mendation of the Ad Hoc Committee, Admiral

Engel, the Academy Superintendent, refused

to grant Mr. Bantum tenure.

* * *

Admiral Engel indicated that it was his

own personal decision, because of a bad

experience he had had in the past, to grant

tenure only after four years on the

faculty. This decision by Admiral Engel was

not published and only came to light after

Mr. Bantum resigned from the faculty.

* * *

It is apparent that the administrators at

Kings Point were rather indifferent to

Mr. Bantum's position. [p. 7]

It is our opinion that the lack of sensitivity

towards the problems of integration demonstra

ted by the personnel at the Academy is clear

evidence of institutional discrimination, [p. 8]

It is a very rare case in this day and age

when we find direct evidence of discrimination.

In most cases discrimination is of a subtle

nature, it is accomplished through various

vehicles. One of the vehicles of discrimination

is failing to adhere strictly to standards and

requirements for position appointments. Another

is in failing to publish changes in requirements,

The evidence is that the Academy is guilty of

both of these offenses. (emphasis added.)

It is my opinion that there is no direct evidence

of discrimination in this case. However, I do

feel that there is substantial circumstantial

evidence which clearly indicates there is dis

crimination against Blacks being appointed to the

faculty at Kings Point. [p. 8]

Having admitted that discrimination occurred,

defendants cannot be heard to contest the validity of their own

finding.

7

In Reynolds v. Coomey, Civ. Act. No. 74-4068-C

(D. Mass, filed March 19, 1976), a finding of discrimination

was made at the administrative level by the agency and plaintiff

brought suit to obtain appropriate relief. The court, in con

sidering a motion by the government for summary judgment or for

dismissal, denied the motion and found the government's admission

of discrimination to be conclusive on the issue. The court

stated: "On the present state of the record, the defendants have

been found guilty of racial discrimination, and there remains now

only the question of whq.t relief will make the plaintiff whole

for the wrongs concededly done to her." (Slip Opinion attached,

at 5-6)

The Supreme Court in its June 1, 1976 opinion in

Chandler v. Roudebush, _____ U.S._____ , 44 U.S.L.W 4709, has in

dicated in a footnote the propriety of such an approach. Holding

that Congress gave federal employees the right to a trial de_ novo

under the 1972 Amendments, the Court stated:

The goal may have been to compensate for the

perceived fact that "[t]he Civil Service Commission's

primary responsibility over all personnel matters in

the Government . . . create[s] a built-in conflict

of interest for examining the Government's equal

employment opportunity program for structural defects

which may result in a lack of true equal employment

opportunity." Senate Report, supra, n.l at 15.

Prior administrative findings made with respect

to an employment discrimination claim may, of course,

be admitted as evidence at a federal sector trial de

novo. See Rule 803(8)(C) of the Federal Rules of

Evidence. Cf. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra,

415 U.S. at 60 n.21. Moreover, it can be expected

that in the light of the prior administrative pro

ceedings, many potential issues can be eliminated

by stipulation or in the course of pretrial proceed

ings in the District Court.

lf.it- V S i.V . ly-llL'H-h 1

8

As a matter of judicial economy and fairness along

the lines of the doctrines of collateral estoppel, res adjudicata,

and preclusion from taking inconsistent positions, the agency's

finding of discrimination which is an admission against its

interest should be conclusive.

B. The Facts Show That Plaintiff Was Denied Equal

Employment Opportunity And Was The Victim of The

Academy's Racially Discriminatory Practices_____

Plaintiff served for two years as a Teaching Fellow

at the Academy. His performance of his duties was of such

quality that he received excellent evaluations from his super

visors, including defendant Negratti.

During the second year of his tenure at the Academy,

two faculty vacancies in the Department of Physical Education

and Athletics became available and plaintiff applied for each.

Despite plaintiff's performance and qualifications, his appli

cations were treated in a perfunctory manner and white applicants

with no previous experience at the Academy hired. Plaintiff

then sought a temporary appointment, but again his request was

perfunctorily denied.

The Academy, as of the date of the Department of Com

merce's decision, had had only one black ever to serve as a regular

faculty member. The Academy has had approximately 90 regular

faculty members during the period in question.

The Instructor-Trainee Program in which plaintiff par

ticipated was intended as a mechanism for preparing minority

group graduate students for faculty positions at the

9

Academy. While there was no assurance of appointment, a

successful participant in the program would be qualified

to compete for a position if one should arise. The

program was part of the Academy's affirmative action

program.

The Academy did not announce the first vacancy

that arose in plaintiff's Department. The Academy did

not establish an Ad Hoc Committee to recruit candidates

as is normally done when filling vacancies. At the time,

that the waiver of the Ad Hoc Committee requirement was

sought,the Academy had already made an offer to a white

applicant, a Mr. Daniel Buckley.

Plaintiff applied for a faculty position during

this period and his application was summarily rejected.

In terms of qualifications required for a faculty position

in the Department, plaintiff was qualified: his bachelor's

degree was in physical education and his master's degree

to be received prior to the effective date of the appoint

ment was also in that field; plaintiff had one and a half

year's college level teaching experience at the Academy.

Mr. Buckley on the other hand, did not meet the required

qualifications for a faculty position: his bachelor's

degree was in history and the master's degree he received

just prior to the effective date of the appointment was

in secondary school administration; he had no college

level teaching experience, having taught various subjects

at the high school level. The Academy had to seek a

waiver of qualification standards in order to hire

10

Mr. Buckley, and the officials did so.

After plaintiff's application for a position was

received, the Academy proceeded to inform him that he could

not be considered for appointment because he had not re

ceived his master's degree and had not completed his second

year of his Instructor-Trainee appointment. These reasons

were clearly pretextual in light of the fact that the offi

cials knew that plaintiff was receiving his master's degree

that summer and stood in that regard in the same position

as Mr. Buckley and that plaintiff's Instructor-Trainee

appointment was three-fourths completed while Mr. Buckley

had no college-level teaching at all.

During the summer of 1972, a second vacancy arose

when the Academy's only black faculty member, Kenneth Bantum,

resigned after being denied tenure by the Superintendent.

The Tenure Committee had reviewed Mr. Bantum's performance

over his three years on the faculty and recommended him for

tenure. The Admiral arbitrarily rejected Mr. Bantum for

tenure. His explanation for this act was that he had decided

not to grant tenure before the completion of four year's

service. The Tenure Committee was apparently totally unaware

of this alleged change of policy since they recommended

Mr. Bantum without hesitation and without a single negative

11

vote. An Ad Hoc Committee was formed to recruit and

select candidates to fill the Bantum vacancy. Plaintiff

applied for this position. The Ad Hoc Committee never inter

viewed plaintiff. The Academic Dean, James Poppe, urged the

Committee to consider plaintiff for the position. Defendant

Negratti reported to the Dean that qualified applicants were

still being sought to fill the vacancy on November 2, 1972.

Two weeks later, despite another exhortation from the Dean to

consider plaintiff, the Committee selected Mr. John Sussi, a

white applicant, to fill the vacancy. The Academic Dean

refused to endorse the selection but Mr. Sussi was hired over

Dean Poppe's objections. Mr. Sussi had a master's degree in

guidance while plaintiff's master's was in the field of physical

education. Plaintiff had successfully taught at the Academy

for almost two years; Mr. Sussi was new to the Academy.

The Academy attempted to overcome the ineluctable

conclusion of racial discrimination arising from the facts

surrounding these appointments by relying on their coaching

needs as justification for these decisions. Mr. Buckley was

hired with collateral duties as basketball coach and

Mr. Sussi as an assistant football coach and track coach.

1/

1/ At the hearing, Admiral Engel attempted to assert that

he had rejected two white faculty members who had been

recommended the year before for tenure after three years

and granted them tenure after four years. The record showed,

however, that the first year these two were considered they

were not highly recommended for tenure by the Committee,

while the second year they were.

12

This attempted justification whether viewed as pretextual or

valid does not overcome the conclusion of racial discrimina

tion in the treatment of plaintiff Brown.

If viewed as a valid business requirement for con

sideration as a faculty member in the Department, the ques

tion must be asked why was plaintiff not informed of this and

efforts made to assure that he obtained coaching experience

during his instructor-traineeship. Plaintiff's demonstrated

abilities and his academic preparation indicate that he would

have performed well. The evidence shows that plaintiff lacked

coaching experience not coaching ability. Plaintiff approached

on his own the baseball and soccer coaches but was told his

assistance was not needed. During the period following

Mr. Bantum's resignation, plaintiff could have been afforded

an opportunity to show his coaching ability. He was not. If

coaching is taken as a valid criterion for employment, then

the Academy operated its Instructor-Trainee Program in such

a way that it would be impossible for plaintiff to ever

qualify, thus denying him equal employment opportunity in

violation of Title VII and the Executive Order.

On the other hand, there is sufficient evidence in

the record to demonstrate that the Academy's reliance on its

coaching needs is pretextual in that the appointments were

for faculty positions as educators and not coaches and the

coaching needs could be taken care of in other ways. The

Academy obtains its coaching staff from three different

sources: (1) some are members of the Department of Physical

13

Education and Athletics, (2) some are faculty members from

other academic departments and (3) others are not on the

faculty but are retained as coaches by the Alumni

Association.

The Rubino-Frost Report in 1971 found the Academy

lacked qualified instructors in the Department. The

Academy hired Mr. Buckley whose lack of qualifications have

already been noted. With regard to the Bantum vacancy, it

should be noted that the Dean Poppe characterized the foot

ball and track requirement added by the Committee as "dis

criminatory and written in such a manner that they fit a

particular candidate." Plaintiff could have assisted the

football coaching staff during the fall of 1972. The

Academy could have hired an outside coach if necessary

instead of writing the football coaching requirement in

tractably into the position. The track coach was a faculty

member in another department and wanted to remain as coach.

Plaintiff could have assisted the track coach as a collateral

14

duty thus meeting the Academy's coaching needs.

The Academy's racially disparate treatment was ex

emplified by the handling of plaintiff's request for "an

excepted temporary position" when contrasted with the hand

ling of Mr. Buckley's appointment. The Academy's officials

went to extraordinary lengths to obtain waivers of the re

gulations and requirements for Mr. Buckley, a white whom

they wished to hire and who lacked the necessary quali

fications for appointment. When plaintiff Brown requested

a temporary position, his request was perfunctorily denied.

At the hearing, defendant O'Grady, the Academy's Personnel

Officer, gave testimony which shows that in May of 1973,

six months after Plaintiff's Request, he learned from the

Maritime Administration's Personnel Officer that surplus

instructor-trainee funds could be utilized to employ

2/

2/ The Assistant Secretary in his final decision speci

fically quoted the following passage from the Examiner's

"Findings and Recommended Decision:"

Mr. Brown had demonstrated his ability. The

Academy places great emphasis on the fact

that they appoint people who are "qualified

for the position". Mr. Brown has demonstra

ted his competency and his qualifications.

The fact that he lacks coaching experience

should not bar him from a position for which

he appears to be well qualified. [Exhibit

"A" p. 2, Exhibit "B" p. 9]

The Examiner went on to say:

While it is not difficult to understand the

need to utilize the positions in the Physical

Education Department to obtain coaches on the

intercollegiate level, there is also a clear-

cut mandate to the administrators of the Kings

Point Academy to place Blacks on the faculty.

[Exhibit "B", p. 9]

15

temporarily a minority instructor [Exhibit "E" at 373-379]. The

surplus funds existed because the Academy had not been able to

employ as many instructor-trainees as they had funds for. If

the Academy had been interested in retaining a qualified black

instructor, if only temporarily, some effort would have been

made to act upon plaintiff's request. None was made and his

request was summarily rejected.

The finding of discrimination made by the Department

of Commerce is more than supported by the facts and evidence in

the record. In Hackley v. Johnson, 360 F.Supp 1247, (D.D.C.

1973) the district court stated in dictum;

Discrimination is a subtle fact.

It is as difficult to identify as the

origin and causes of many odors. If

it is present anywhere in the federal

establishment, it must be promptly

extinguished. 360 F.Supp 1252.

Discrimination at the Academy has been detected and

must be promptly extinguished.

16

III.

HAVING ESTABLISHED UNLAWFUL DISCRIMINATION

PLAINTIFF IS ENTITLED TO THE FULL RANGE OF

EQUITABLE RELIEF PROVIDED BY TITLE VII

The United States Supreme Court has made it clear that

a federal employee in a Title VII action is entitled to the same

rights as a private employee and that the district courts have

broad equitable powers to fashion appropriate relief to make the

victims of discrimination whole by restoring them as far as possi

ble to the position where they would have been were it not for

unlawful discrimination.

In Chandler v. Roudebush. _____ U.S._____ , 44 U.S.L.W

4709, (June 1, 1976) the Supreme Court unanimously held that federal

employees have the same right to a trial de_ novo as is enjoyed by

private sector or state government employees under the amended Civil

Rights Act. The Court commenced its discussion of the case with

the following statement:

In 1972 Congress extended the protection of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 253, as amended

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq.(1970 ed. Supp.IV) to employees of

the Federal Government. A principal goal of the amending

legislation, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

Pub.L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103, was to eradicate "tentrenched

discrimination in the Federal service1" Morton v. Mancari,

417 U.S. 535, 547, by strengthening internal safeguards

and by according " falggrieved \federal) employees or appli

cants . ♦ . the full rights available in the courts as are . ,

granted to individuals in the private sector under Title VII-— '

The issue presented by this case is whether the 1972 Act

gives federal employees the same right to a trial de_ novo

of employment discrimination claims as "private sector"

employees enjoy under Title VII.

1/ S.Rep. No.92-415, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess.,

16(1971), hereinafter cited as Senate Report.

44 U.S.L.W 4710 (emphasis added).

17

As noted above, the Court unanimously held that federal employees

were entitled to the same right to a trial de_ novo as "private

sector" employees enjoy under Title VII.

Although the Chandler decision was specifically

addressed to the trial de_ novo issue, it clearly follows from

the above quoted language of the court that federal employees

also have the same right to all the relief afforded to a success

ful private employee under Title VII. Section 717(d) of the 1972

Amendments makes this clear. Section 717(d) gives federal employees

the right to bring civil actions for discrimination in employment

and explicitly provides that "[t]he provisions of Section 706(f)

through (k), as applicable, shall govern civil actions brought

hereunder." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (d) . Section 706 (g), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(g) is the remedial provision of Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act and directs a district court to "order appropriate

relief" upon finding that an unlawful employment practice has been

committed. Section 706(k), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) allows a district

court the discretion to grant the prevailing party a reasonable

attorney's fee as part of the costs.

3 / §706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g), states in

pertinent part:

If the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging

in an unlawful employment practice charged in the

complaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from

engaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include, but is not limited to, reinstate

ment or hiring of employees, with or without backpay

. . . or any other equitable relief as the court

deems appropriate.

18

The Supreme Court recently addressed the breadth and

flexibility of the remedial provision §706(g) of Title VII in

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 44 U.S.L.W 4356 (U.S. March

24, 1976). In considering retroactive seniority as a valid correc

tive device, the Supreme Court incorporated in its opinion the

following from the legislative history:

"The provisions of [§706(g)] are intended to give the

courts wide discretion exercising their equitable

powers to fashion the most complete relief possible

. . . [T]he Act is intended to make the victims whole

and . . . the attainment of this objective ! I I re-

quires that persons aggrieved by the consequences and

effects of the unlawful employment practices be, so

far as possible, restored to a position where they

would have been were it not for unlawful discrimination "

(quoting Section-by-Section Analysis of H.R. 1746,

accompanying the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972-Conference Report, 118 Cong. Rec. 7166, 7168 (1972)).

44 U.S.L.W at 4360 (Emphasis added).

The Court proceeded to state that "this is emphatic confirmation

that Federal courts are empowered to fashion such relief as the

particular circumstances of the case may require to effect resti

tution . . . " Id.

In Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 45 L.Ed.

2d 280 (1975), the Court indicated that district courts in effec

tuating remedial relief should recognize that the objective is

"to make persons whole for injuries suffered on account of em

ployment discrimination." 422 U.S. at _____ , 45 L. Ed. 2d at 297.

In doing so, " ft]he injured party is to be placed, as near as may

be, in the situation he would have occupied if the wrong had not

been committed." Id.

Under the circumstances of this case, plaintiff was

entitled to an offer of immediate employment with appropriate

19

seniority and rank, to back pay for any income loss he may have

suffered and to a reasonable attorneys fee, as is more fully

demonstrated below. "Congress clearly intended to give public

employees the same substantive rights and remedies that had pre

viously been provided for employees in the private sector; . . . "

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976, 981 (D.C.Cir. 1975)

When Congress amended Title VII in 1972 to include the

Federal Government, it mandated that "[A]11 personnel actions

affecting employees or applicants for employment . . . shall be

made free from any discrimination based on race, color, religion,

sex or national origin " 42 U.S.C.§2000e -16(a) . To achieve this

end, the Congress authorized the Civil Service Commission "to

enforce the provisions of subsection (a) through appropriate

remedies, including reinstatement or hiring of employees with or

without back pay, as will effectuate the policies of this section

. . ." 42 U. S. C . §2000e -16(b) . (emphasis added).

It is clear from the facts of this case that while

discrimination was found, the remedies were not sufficient to

effectuate the policies of this section.

A. Plaintiff is Entitled to Injunctive Relief Requiring

the Academy to Offer Him Immediate Appointment to the

Kings Point Faculty____________________________________

The Department of Commerce and the Civil Service Com

mission could have ordered plaintiff's appointment to the faculty

either in lieu of Mr. Buckley or Mr. Sussi or as an additional faculty

member without a preexisting billet. This was not, however,

necessary since the record of the hearing showed that a faculty

20

position was available as of December 1973. Defendant Zielinski

retired and was not replaced.

Injunctive relief requiring the Academy to offer plain

tiff an appointment is clearly appropriate and dictated by the

Department of Commerce's decision that plaintiff be offered th

AJnext available vacancy.

The Academy cannot be allowed to determine when it feels

it is convenient to grant plaintiff the relief to which he is

entitled. To allow the Academy to do so is to make meaningless

4 / Defendant O'Grady admitted at the hearing that such a

vacancy existed but testified that he did "not believe

we are going to fill that position. It has been our

feeling that the department is overstaffed." [Exhibit

"E" at 362-363] .In reply to this contention that the department

is overstaffed, plaintiff draws the Court's attention

to the "Rubino Report" which was introduced as Com

plainant's Exhibit 1. Defendants have admitted that

the report showed the Physical Education Department to

be understaffed and in need of qualified people, in

dividuals with degrees in physical education. Plain

tiff also calls the court's attention to Admiral Engel's

testimony in which he expressed his own dissatisfaction

with the quality of the PE program being offered at the

Academy and stated that he wanted it to have a viable

PE program capable of teaching a young man how to take

care of his body. [Exhibit "E" at 273, 276-278].

When questioned as to whether having qualified,

trained physical educators would be an important

aspect of achieving this, he replied "Absolutely."

[Exhibit "E" at 278]. Once again, plaintiff must

point to the Examiner's and the Department's finding

that " . . . Mr. Brown's services as a Teaching Fellow

at the Academy were satisfactory or better . . . Mr.

Brown had demonstrated his ability . . . (he) has

demonstrated his competency and his qualification."

21

the concept of remedial relief.

With respect to the conditions of plaintiff's appoint

ment as a regular faculty member, the Court need no further

citation than Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.. 44 U.S.L.W.

4356 (U.S. March 23, 1976), for the proposition that an award

of retroactive seniority to the date that plaintiff would have

assumed a position on the faculty of the Academy had it not been

for the Academy's discriminatory refusal to hire is appropriate

under §706(g) of Title VII. If plaintiff desires to accept a

position on the faculty at the completion of this litigation, as

a matter of equity, he should be eligible for consideration for

tenure after a minimum period of time and should be appointed

at a commensurate step on the pay scale.

5 / Courts have granted successful Title VII claimants relief

in the form of an award of "front pay" in cases where the

defendants are unable to place the claimant in his right

ful place, thus compensating the claimant monetarily until

an appropriate position becomes available. See, Franks

v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra; Patterson v. American

Tobacco Co., _____F .2d _____ , 11 E.P.D. 5 10,470 (4th Cir.

1976) and White v. Carolina Paper Board Co., 10 E.P.D.

f 10,470 (W.D.N.C. 1975).

22

B. Plaintiff is Entitled To Back Pay For Any Income

Lost Because of the Academy's Failure to Appoint Him

Plaintiff from the filing of his formal statement to

the investigator has sought back pay and is entitled to it. Such

back pay is the difference between his interim earnings or the

amount earnable with reasonable diligence, see 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g),

and what he would have earned if he had been retained at the Academy

as an Assistant Professor at an appropriate grade level.

Sections 706(g) and 717(b) of Title VII specifically

identify an award of back pay as an appropriate remedy under

Title VII.

In Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, ____ U.S. _____ , 45

L.Ed 2d 280 (1975), the Supreme Court has spoken persuasively

about the importance of back pay. Citing Griggs v. Duke Power

Co.,401 U.S. 424, 429-30, 28 L.Ed 2d 158, that the primary objective

of Title VII was a prophylactic one "to achieve equality of

employment opportunities and remove barriers that have operated

in the past to favor an identifiable group of white employees

over other employees," the Court went on to state:

Backpay has an obvious connection with this

purpose. If employers faced only the prospect

of an injunctive order, they would have little

incentive to shun practices of dubious legality.

It is the reasonably certain prospect of a backpay

award that "provide[s] the spur or catalyst

which causes employers and unions to self-

evaluate their employment practices and to

endeavour to eliminate, so far as possible,

the last vestiges of an unfortunate and

ignominious page in this country's history."

(citation omitted)

45 L.Ed 2d 296-297.

23

The Court further stated:

. . . [G]iven a finding of unlawful discrimination,

back pay should be denied only for reasons which,

if applied generally, would not frustrate the

central statutory purposes of eradicating discri

mination throughout the economy and making persons

whole for injuries suffered through discrimination.

45 L .Ed 2d 298-299

Clearly, when the federal government is the discriminating party,

especially in light of the Executive Orders, there is a great

need for all the prophylactic measures possible.

An award of back pay while of a prophylactic nature

has been held not to be punitive in nature. The courts have

developed a strong body of law regarding back pay in Title VII

actions against private employers. "Back Pay is clearly an

appropriate remedy for Title VII violations." Head v. Timken Roller

Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870, 876 (4th Cir. 1973). "The back pay

award is not punitive in nature but equitable-intended to restore

the recipients to their rightful economic status absent the effects

of the unlawful discrimination." Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444

F.2d 791, 802 (4th Cir. 1969), cert. den. 404 U.S. 10006 (1971') . See,

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir.

1974); U.S. v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 921 (5th Cir. 1973).

See also Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra; Bowe v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969); Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122, 1125 (5th Cir. 1969); U.S. v.

Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d 112, 121 (1972); U.S. Georgia

Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 921 (5th Cir. 1973); Moody v. Albemarle

Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134, 142 (4th Cir. 1973).

Because of the non-punitive nature of back pay, an

24

employer's good faith actions do not constitute a valid ground

for the denial of an award . Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

supra; Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., supra. The issue

is whether a discriminatee was economically injured. Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 260 (5th Cir. 1974).

"Neither benign neglect nor activism will be judicially tolerated

if the outcome of such practices is racially discriminatory and

results in monetary loss." Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp.,

495 F .2d 437 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1033 (1974)

In Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., supra, the

Court concluded that as a matter of law, a discriminatee is pre

sumptively entitled to back pay unless evidence is presented to

establish that an alleged discriminatory practice did not affect

him. In order to deny back pay, a defendant must show by "con

vincing evidence" factors which would have retarded or prevented

the employee's progression. Any doubts should be resolved in

favor of the discriminatee who is the innocent party. Baxter v.

Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., supra.

Applying the above principles to the area of federal employ

ment discrimination, an award of back pay to the plaintiff in the

instant action is incontestably proper. In Day v. Matthews,

_______ F.2d________ , 11 E .P.D. 510,725 (D.C. Cir. 1976), where

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare did not dispute

a finding of discrimination but denied the federal employee any

of the relief sought, namely retroactive promotion and back pay,

the Court of Appeals remanded the case to the district court

directing it to award back pay and retroactive promotion unless

25

the defendant, HEW, by clear and convincing evidence, proved that

even absent the admitted discrimination, the plaintiff still

would not have been selected. The burden, then, according to

Day,is not on the discriminatee to show that he would have

gotten the position but for unlawful discrimination; the burden,

rather, is on the defendant to show that under no circumstances

would the discriminatee have gotten the desired position, even

absent discrimination. Accord, Cooper v. Allen, 467 F.2d 836

(5th Cir. 1972) .

Federal Courts have awarded back pay to prevailing

plaintiffs against federal agencies. Robinson v. Warner,

8 E.P.D. 59452 (D.D.C. 1974); Smith v. Kleindienst, 8 F.E.P.

Cases 5752 (D.D.C. 1974) , aff1d in part and revs1d in part sub

nom. Smith v. Levi, ____F.2d______ , 11 F.E.P. Cases 51308

(reversed as to award of interest) (D.C. Cir. 1975) ;

McLaughlin v. Calloway, 9 F.E.P. 510,098 (S.D. Ala 1975).

C. As a Prevailing Litigant, Plaintiff is Entitled

to a Reasonable Attorney's Fee under Section 706 (k)

Section 706 of Title VII provides that"[i]n an action

or proceeding under this Title, the court, in its discretion,

may allow the prevailing party. . . a reasonable attorney's

fee as part of the costs. . . ." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (k). The

1972 Amendments to Title VII incorporated §706 (k) to govern

civil actions brought pursuant to the amendments. 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-16 (d).

The propriety of granting attorney's fees to success

ful claimants has been addressed in numerous cases. The Fifth

Circuit, in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d

26

714 (5th Cir. 1974) enumerated several guidelines to assist in

the determination of what is a just and reasonable fee, and

stated that the purpose of §706 (k) was to effectuate the

Congressional policy against racial discrimination, and to

recognize the significance of private enforcement of civil

rights legislation. In employment discrimination cases, a

plaintiff not only remedies his own injury, but also that of

the public, thus vindicating an important Congressional policy

against discriminatory employment practices. Alexander v .

Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). An award of

attorney's fees thus serves as an encouragement for an

aggrieved litigant to pursue fully his right not to be discrimi

nated against in the proper forums.

As Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, supra,

indicated, the statute was passed to enable clients to obtain

effective counsel who would be willing to undertake a complex

action involving sometimes tedious and expensive preparation.

An award of attorney's fees provides an incentive for attorneys

to accept such cases, especially when:

[E]xhortations towards citizen

participation can sound some

what hollow against the background

of the economic realities of

vigorous litigation. In many

public interest cases... the

average attorney or litigant must

hesitate, if not shudder, at the

thought of'taking on' [a finacial-

ly powerful] entity . . . . with

[uncertain] prospect of financial

compensation for the efforts and

expenses involved.

27

U. S. v. Operating Engineers, Local Union 3, 6 E.P.D. 58946 (N.D.

Calif. 1973).

The Supreme Court in Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 45 L.Ed. 2d 280 (1975), indicated that the

rationale of Newman v. Pigqie Park, 390 U.S. 400 (1968), could

equally be applied to the attorney's fees provision of Title

VII. Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra at 295. Indeed,

Title VII litigants, when acting on behalf of a class and

obtaining injunctive relief, are no different than the Title

II litigants referred to in Newman v. Pigqie Park, supra.

See Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F.Supp 709, (E.D. La

1970) aff'd per curiam 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971).

In Newman, the Court stated:

... If successful plaintiffs were

routinely forced to bear their

own attorney's fees, few aggriev

ed individuals would be in a

position to advance the public

interest by invoking the injunc

tive powers of the federal courts.

Congress, therefore, enacted the

provision for counsel fees not

simply to penalize litigants. . . i

but. . . to encourage individuals

injured by racial discrimination

to seek judicial relief. . . .

390 U.S. 402

In accord with Congressional policy and legislative

intent, courts have not been reluctant to award attorney's fees

for work done at both the administrative and judicial levels in

federal employment litigation. In Parker v. Matthews, 11 E.P.D.

510,821 (D.D.C. 1976), such fees were awarded pursuant to a

settlement of a federal employment action. No distinction was

made for time spent on the administrative and judicial levels.

In making the award, the court observed that in civil rights

- 28

litigation, litigants assume the role of private attorneys

general who vindicate a Congressional policy against racial

discrimination. "It is only through attorney's fees provisions

that litigants can be assured of the competent counsel they need

for the effective enforcement of their right not to be discri

minated against" . Id. In accord with Parker v. Matthews is

Smith v. Kleindienst, 8 F.E.P. Cases 753 (D.D.C. 1973), aff'd.

sub, nom., Smith v. Levi, 11 F.E.P. Cases 1308 No. 74-1939 (D.C.

Cir. 1975). It is also interesting to note that a twenty-five

percent incentive fee or bonus was awarded in Parker, a case

which did not involve novel or complex legal issues.

Similarly, the court in McLaughlin v. Calloway, supra,

awarded attorneys' fees to the successful federal plaintiff under

the 1972 Amendments to Title VII.

In Johnson v. U.S.A., Civ. No. H-74-1343 (D.Md.,

Memorandum and Order of June 8, 1976), the court awarded plain

tiff attorneys' fees on the basis of his having prevailed on the

administrative level. The court made clear that attorneys'fees

were proper regardless of whether the plaintiff prevailed on the

administrative level or at the judicial level. The court ex

plained:

Moreover, the clear Congressional intention in

enacting §717 in 1972 was to create an administrative

and judicial scheme for the redress of federal em

ployment discrimination. Brown v. General Services

Administration, [44 U.S.L.W 4704] at 4706. Sections

717(b) and (c), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16(b) and (c) establish

complementary administrative and judicial enforcement

mechanisms to achieve the statutory purpose. Idem at

4706. It is therefore not material whether the party

seeking the award prevailed at the administrative

29

level or at the judicial level- Both are

a part of the same enforcement mechanism

established by the statute. If he is re

presented by an attorney at either or both

levels, a successful claimant is entitled

to an attorney's fee to be awarded in the

discretion of the court.

(Slip Opinion attached at 7)

In the instant case, counsel was needed to consult

with the plaintiff, make discovery, prepare and present the

documentary evidence and testimony given at the administrative

hearing, prepare the administrative appeal, and bring this suit

in federal district court. Were it not for plaintiff's

vigorous prosecution of this matter, it is very questionable

whether the Academy would ever have become aware in the reason

ably foreseeable future that the federal equal employment

opportunity laws and regulations are to be taken seriously.

For this reason and those previously asserted, the plaintiff

is entitled to reasonable attorneys' fees.

30

CONCLUSION

Federal employees are entitled to the same rights under

Title VII as are enjoyed by employees in the private and local

government sectors. Plaintiff is entitled to summary judgment on

the issue of discrimination on the basis of defendants' admission

of discrimination and the facts of this case. As a result,

plaintiff is entitled to the relief prayed for by Count One of his

Amended Complaint, including an offer of instatement, back pay and

an award of a reasonable attorneys' fee. For the foregoing reasons,

Plaintiff's Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Entitlement To

Relief Requested By Count One of His Amended Complaint should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

JAMES C. GRAY, R.

ULYSSES GENE THIBODEAUX

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys For Plaintiff

31

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

Civil Action

No. 74-406S-C

HELEN H. REYNOLDS

v.

PATRICK F. COOMEY,

District Director,

U.S. Immigration and

Naturalization Service, et al

MEMORANDUM and ORDER

March 19, 1976

CAFFREY, Ch.J.

This is a civil action brought pursuant to Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 USCA §2000e,

et sea. Plaintiff challenges the sufficiency of the remedy

accorded her as a result of a United States Department of

Justice Complaint Adjudication Officer's decision that she

was discriminated against because of her race in the course

of her seeking promotions while .employed by the United States

Immigration & Naturalization Servi.ce (INS). The matter came

before the Court upon the defendants' motion to dismiss or

for summary judgment.

It is undisputed that plaintiff, a black woman, has

been an employee in the Boston District Office of the INS

since 1941, at which time she entered employment as a Clerk-

Typist, CAF-1. She has been continuously employed by the INS

since that time except for two periods of maternity leave.

As of the time of the filing of this action, her last

-yyj «r. •.?

jW ff* • «> m -' - i

promotion was in 1961 when she was promoted to the grade of

GS-5.

The instant complaint is addressed to allegedly dis

criminatory acts by defendant Patrick F. Coomey, who was

Acting District Director, Boston District Office, INS, in

February 1961, and became District Director on April 29, 1971.

Plaintiff first met with an Equal Employment Opportunity

(EEO) counselor in November 1973, at which time she alleged

that she was discriminated against because of her race in

not being selected for the position of Assistant Chief,

Records Administration and Information Section (RAIS), a

GS-7 position, on October 2, 1973. After informal attempts

to resolve the complaint failed, a formal complaint of

employment discrimination was filed which cited defendant

Coomey as the discriminating official. Plaintiff alleged that

a pattern of discrimination was established on the basis of

prior non-selections for promotion in 1970, 1971 ancj 1972.

Plaintiff was notified on February 6, 1974 by the INS

EEO officer that, upon investigation,-her allegations of

discrimination were unsupported. Subsequent to that

notification, and pursuant to her request therefor, a hearing

was held on April 22, 1974 before a U/ S. Civil Service

Commission Examiner. The plaintiff and INS were represented

by counsel, and oral and documentary evidence was presented.

After the hearing, the Examiner reported his findings

and proposed remedy. The principal issue address,-cl by the

Hearing Examiner in his report was framed by him as follows:

"Were [plaintiff's] race (Negro) and/or

sex (female) considerations in her non

selection for the position of Assistant

Chief, GS-7, RAIS, on October 2, 1973?"

issues were also raised and addressed by the Examiner

in his report:

" . . . with respect to seven previous pro

motional opportunities on which [plaintiff]

relies . . . to base her allegations of a

pattern of discrimination ending in [plaintiff's

nonselection in October 1973]."

The Examiner found that:

"Mrs. Reynolds was in a dead-end position

in the Citizenship Branch from which she

could not reasonably expect any promotion

notwithstanding her record of good attendance,

five performance awards, excellent recommenda

tions for promotion by her first and second

line supervisors, and approximately 31 years

of service with INS."

Findings, p. 14, fll4.

The question for the Examiner thus became whether plaintiff

was denied equal employment opportunity by INS due to the fact

that she was

"'locked in' the Citizenship Branch, with

little or no opportunity-to broaden her

experience in the work done in other

Branches of [INS], so that she could

compete with others for [job promotions]."

Findings, p. 14, J14.

The Examiner found that the plaintiff was indeed denied

equal opportunity for promotion and, in this respect, was the

victim of what he characterized as "systemic" racial dis

crimination.

- 3 -

The Examiner found that the Northeast Region of the INS

has a "Plan of Action for Equal Employment Opportunity," in

which there are objectives entitled "Enhancement of employee

skills and upward mobility." (Findings, p.- 14,«I14). These

objectives prescribe methods by which the particular agency

can meet the goals of the Plan. The Examiner found that

plaintiff's first and second line supervisors "knew little or

nothing" about INS's Plan of Action, (see Transcript of

Hearing, April 22, 1974, at pp. 51, 55, 61, 62, 65) notwith

standing the fact that the INS

"has made a commitment and has an obligation

to make certain that the affirmative action

plan for equal opportunity is real, workable,

and utilized by those responsible for

achieving its goals."

Findings, pp. 14-15, <114.

The Examiner thus concluded that

" . . . Mrs. Reynolds, as a minority group

. . . employee . . . was not given con

sideration for career development under

the INS affirmative action plan and that

failure to do so effectively deprived her

of opportunity for promotions which non

minority employees enjoyed,-solely by

virtue of their positions’ in other organized

units."

Findings, p. 15, Conclusions, #2.

Pursuant to the Examiner's conclusion that, broadly

viewed, the evidence supported plaintiff's allegation of

racial discrimination, the Examiner recommended a course of

action designed to give plaintiff "true equality for pro

motional opportunity."

- 4 -

The Examiner recommended that the plaintiff be provided

a career development plan together with priority consideration

for promotion "to the next position vacancy which shall become

available for which she would be among the best qualified

candidates . . . " Findings, p. 16. He also recommended that

supervisory personnel of the Boston Office, INS, be given

training relative to the Agency Plan of Action.

The Examiner's findings and recommendations were adopted

and incorporated by the Complaint Adjudication Officer in his

opinion dated July 22, 1974. It was further ordered by the

Complaint Adjudication Officer that monthly reports be made

to the Director of EEO until plaintiff was given priority

consideration resulting in her promotion.

This matter was briefed and argued orally in this Court

by counsel for the parties. At the hearing the Assistant

U.S. Attorney representing the federal defendants conceded

that plaintiff has been a victim of racial discrimination.

The principal area of controversy between plaintiff and the

federal defendants at the hearing was whether this Court

should grant a hearing de novo oh the entire matter or merely

conduct a hearing as to remedy.

In view of the Government's concession that there was

merit to the discrimination claim, no policy of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act can be advanced by conducting a chi novo

hearing on the merits.

On the present state of the record, the defendants have

been found guilty of racial discrimination, and there remains

-5-

for decision now only the question of what relief will make

plaintiff whole for the wrongs concededly done to her.

Accordingly, it is

ORDERED:

The defendants' motion to dismiss or for summary

judgment is denied, and the case will stand for a hearing on

remedy and damages.

Andrew A. Caffrey, Ch.J...

0

- 6 -

in the united s t m t s district court

FOR TIIR DISTRICT OF MARYLAND

• JAMES A. JOHNSON :

Plaintiff

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA :

WILLIAM B. SAXBE, Attorney

General of the United States :

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF

T1IF. ARMY ;

HOWARD H. CALLAWAY, Secretary

of the United States :

Department of the Army

UNITED STATES CIVIL SERVICE

COMMISSION

and

ROBERT E. HAMPTON, Chairman of

the United States Civil

Service Commission

Dofondants

Civil No, H-74-1343

Kenneth L. Johnson, Baltimore, Maryland, for plaintiff. '

Daniel M. Clements, Assistant United States Attorney, ,

Baltimore, Maryland, for defendants.

MEMORANDUM -AND ORDER

Claiming discrimination in his employment because of his

race, plaintiff has brought this action under Title VII of the <. . .

. Civil Rights Act of 1964. Named as defendants are various officials

and agencies of the United States.

The controversy in suit has a lengthy history’ in this

Court and before various federal administrative bodies. Plaintiff

initially filed suit in this Court on July 5, 1973. Johnson v.

Froohlke, Civil No. 72-677-H. Following a hearing in open court on

January 4, 1973, the government's motion to dismiss the complaint

was denied. Thereafter, the government moved to remand the case

to the Civil Service Commission for a hearing and determination on

the merits of plaintiff's claim that he was the victim of continuing

racial discrimination in his civilian employment by the United'''

States Army ar. an Illustrator. Finding that the plaintiff had.,

never received a full administrative hearing or determination on

the merits of his claim and that the United States Civil Service

Commission was now willing to grant plaintiff a full hearing on

■the merits, this Court entered an Order on June 25, 1973, remanding '

.the case to the Commission for such a hearing and determination,

without prejudice to the right of the plaintiff to-.refilc an action’

in this Court if he were denied the relief he sought.

A black male, plaintiff had been hired by the United ; . “. }..

States Army as an Illustrator at the Training Aids Center ("TAC"),-

Fort Meade, Maryland, on August 1, 1961. In this and his earlier

suit, plaintiff claims that he was refused promotion because of his

•race, and he also asserts various other claims of racial discrimin

ation at TAC. On July 2, 1968, a vacancy in the position of ' ...

Supervisory Illustrator was announced. Two persons applied for -the

job,; the. plaintiff and a Mr. Anthon Allred, a white male. The"

Director of the TAC, Mr. William Gulley, also white, selected x

Allred, and the latter assumed the higher position on September 8,

1 9 6 8 . Allred resigned the position as of December 20, 1968, but

the position was left open until plaintiff finally filled it in

1975. • < ■?....

On August 31, 1970, plaintiff filed a formal complaint

of discrimination, alleging that he was not selected for the job

because of his race. The Equal Employment Opportunity Officer at

Fort Meade rejected the complaint as untimely. On February 3, 1972,

plaintiff filed another complaint alleging, inter alia, that he

had been subjected to a continuing pattern of discrimination which

had prevented him from being promoted to the position of Supervisory

-Illustrator. On March 8, 1972, the EEO Officer rejected this-

second complaint as al*;o being untimely. Plaintiff appealed the

decision to the Board of Appeals and Review, but the decision was

affirmed. Plaintiff's first suit in this Court followed.

1

Pursuant to this Court's Order of June 25, 1973 in Civil

1 !•

No. 72-677-H, the Civil- Service Commission returned the case to the

Army for processing under Part 713 of the Commission regulations.

The complaint was investigated by a representative of the U. S. Army

Civilian Appellate Review Office, and a report was submitted on •

April 17, 1974. The investigator made the following recommendations.

A. That the complainant be informed in writing ,

that his allegation of discrimination in the ' ̂ ‘

matter of denial of promotion because of his race

(black) is substantiated.

B. That, the complainant be promoted to-the posi- >.

tion of Supervisory Illustrator, GS-1010-09, in

accordance with the provisions of Civilian

Personnel Regulation 713.B-16d.

C. That, the complainant, be accorded full oppor-

tunity to acquire training in the knowledge, skills’

and experience required for more responsible posi-

t.ions, in keeping with the EEO Plan of Action

Command Objective relating to the.situation wherein

supervisory positions reflect an imbalance by race

and sex. s .

D. That appropriate measures be taken to determine,

the extent of culpability of managers, supervisors ,

and program officials in the discriminatory practices

cited herein and corrective action be initiated j

accordingly. . »• • .

On May 14, 1974, the Post Commander at Fort Meade issued

his letter of decision, rejecting recommendations "A" and nBn,

approving recommendation "C", and approving recommendation D with

a modification which substituted the word "managerial’* for the word

"discriminatory" in line three. Dissatisfied with this decision,

s s

plaintiff requested a hearing by an EEO Complaints Examiner. ., .

A hearing was held on July 10 and 11, 1974, at which

plaintiff appeared with counsel and testified. Thereafter, the

Examiner submitted his report and recommendation to the Army on

October 12', 1974. The Examiner recommended a finding of discrimina-• ■ ... i .

tion, .and, noting that since July 1, 1973 the Art Section had had .■•••

sufficient employees to warrant the appointment of a supervisor,'

further recommended that plaintiff be promoted to the position of

Supervisory Illustrator retroactive to February 4, 197(J, which was

two years before plaintiff had filed his second complaint., It was

also recommended that the Director of the TAC be,required to attend

Van appropriate EEO course and that the Post Commander monitor

personnel actions in the. TAC so as to assure that all employees were

treated equally as to promotions, awards and training. ■ ....

The Army approved the Examiner's report and recommendation

on November 15, 1974, and by letter of December 11, 1974, offered '

plaintiff his promotion retroactive to September 8, 1968, rather

than merely to February 4, 1970, as the Examiner had suggested.•

However, plaintiff had meanwhile instituted this action on December *

9, 1974, seeking (1) promotion with back pay, (2) compensatory and v

punitive d a m a g e s (3) a declaratory judgment, (4) an injunction .

against -future employment discrimination, and (9) costs and attor

ney's fees.

Presently before the Court are cross-motions for summary

judgment. Both sides have submitted memoranda of law, and the

defendants have also filed the 459-page transcript of the adminis- '

trative hearing held in July 1974 and numerous documentary..exhibits

which were considered by the various administrative officials. It

has been agreed by the parties that, the pending motions should be

decided by the Court on the extensive record presently before it

without the necessity of a hearing. The parties have further aqreed■

that only two issues remain in this case, namely (1) whether

plaintiff is entitled to an order enjoining defendants from future •

acts of discrimination and (2) whether plaintiff is entitled to

recover a reasonable attorney's fee and costs from defendants.

'•* I _ •

Injunctive Relief ,,

In his motion for summary judgment, plaintiff asks this

Court to '"enjoin the Defendants from discriminating against the

'Plaintiff because of his race (black); * * * Flaintiff contends

that because of what has happened in the past, he is entitled to

an injunction to prevent future racial discrimination against him.

The record here does not "sqpport plaintiff's £laim of

• •• j '

.entitlement to a permanent injunction prohibiting future discrimin---

atory acts. On the contrary, the undisputed facts in this case show

• that no injunction should now issue. As a result of the various

•administrative proceedings and action taken by the Army pursuant

thereto, plaintiff has now gained everything he was seeking when he

first asserted his claim against the Army. Ho has been promoted "..

to the position of Supervisory Illustrator; his promotion has.been

made retroactive to September 8, 1968, which was the first date the

position was filled; and he has been awarded full back pay including

appropriate yearly increases. In addition, the Director of the

Center where plaintiff works has been required to have further equal

employment opportunities training. Finally, the Army has undertaken

to monitor personnel actions at the Center more closely to prevent

future racial discrimination as to promotions, awards and training.

Now that plaintiff is a Supervisory .Illustrator, any

claim of future discrimination against him must necessarily involve

facts quite different from those which supported the showing of

discrimination in the past. The record does not. indicate that

there is any position open at. this time to which plaintiff seeks to

bo promoted. No allegation to such effect is contained in the

complaint, nor has plaintiff alleged that since he assumed his new -

job he has been the subject, of any other kind of racial discrimina

tion.: Should such discrimination occur at any time" in the future,,

plaintiff is of course free to file another action in this Court,

after first undertaking his administrative remedies.

, For these reasons, this Court will not enter a permanent

injunction .against the defendants prohibiting future discriminatory

acts against plaintiff. When the discriminatory practice has been

terminated and is not likely to recur, it is proper for a court to

deny injunctive relief. Williams v. General roods Coro., 492 F.2d

399, 407 (7th Cir. 1974).

IT

Costs and an Attorney's Fee

This action was brought by"plaintiff under'Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.s.C. §2000e et seq. Until it

was amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Title

VII,provided no protection for federal employees. That enactment

added §717 to the 1964 Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16, which proscribes

for the first time federal employment discrimination and establishes

an administrative and judicial enforcement system. See Drown v.

General Services Administration, 44 U.S.L.W. 4704 (U.S. June 1, 1976).

‘ . Section 706(k) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000b 5(k)

' as'.follows:

(k) In any action or proceeding under this sub

chapter the court, in its discretion, may allow

the prevailing party, other than the Commission

or the United States, a reasonable attorney's

fee as part of the costs, and the Commission

and the United States shall be liable for costs

the same as a private person.

,provides

In Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 1

421 U.S. 240 (1975), the Supreme Court held that.there must be a 1

specific statutory authorization for the a;/nrd of an attorney's fee

in a civil action brought in federal court. In view of the specific

language of Subsection (k) quoted above (and defendants so concede),

there is no longer any question' that a federal employee who prevails

in a. Title VII action may in the discretion of the Court be allowed .''•••i

costs and attorneys’ fees to be paid by the United-States. The*

defendants in this case argue that no such award should be made

here because plaintiff was not "the prevailing party" in this'liti-

gation and because the relief plaintiff secured was not’ obtained

in ari "action or proceeding" within the meaning of the statute;- >--t

This Court would disagree with both of these contentions and will* i-accordingly award plaintiff a reasonable attorney's fee. •

In arguing that to recover his attorney's fee a party must

prevail in court rather than in administrative proceedings,

defendants’ overlook both the history of this litigation and the

Congressional intent in adding §717 to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Plaintiff did originally sue in this Court for relief, and it was

the Army which moved for a remand so.that the dispute could be .

heard initially in administrative proceedings. Not completely ’’

satisfied with the relief afforded at the administrative level,

plaintiff later re-instituted suit, which is now this pending action.

Certainly, the fact that plaintiff had already filed suit in'this .

Court and had been expressly authorized to return here if dissatisfied

' with*.th<v a*uiniotrft:telv»i-kk«*uiv.<» i,nd n marked effect on the A m y s

•acceptance-of the findings made by the" Honriwr Examiner., 'Thu? JV’the,-

administrative anti jud i c in l • proceediugs were part and parcel of. the-

same litigation for which an attorney's fee is now sought. • , •.

• t . . . , a i • * * i # ■ • •Moreover, the clear Congressional intention in enacting,.

-V i - V . ! *

- 1 *-T.'/dT in'107?. wan -to create an administrative and judicial schema

v ,l v . - t ■ ■ ' ; • • ■ • , V * ' ' ' • ■'for the redress of federal employment discrimination. Drown v. > ! '

■General Services Administration, s_uprâ , 4 4 11.!'.I..W. at.'4706’. ^Sec

tions 717(b) and (e), 42 U.S.C. 52000e-16(b) and (c), establish- .

complementary administrative and judicial enforcement mechanisms to?

achieve the statutory purpose. M o m at 4706. It is therefore not

"^material whether the party seeking the award prevailed at the '-.-'' I

administrative level or at the judicial level. Both are a part of

' the same enforcement mechanism established by the statute.-. If he

' is .represented bv an attorney at. either or both levels, a successful

claimant is entitled to an attorney's fee to be awarded i« the •

dis’eretion of the Court. ' ■ •

. In this particular case, plaintiff through administrative

proceedings was restored to the position he sought- retroactive' to

September 8, 1968 and was awarded full back pay. Clearly h e -is theV* «"prevailing party" contemplated by the statute. The fact that this

Court did not enter a permanent injunction against possible'future

discrimination by.defendants hardly detracts from the substantial •

victory von by plaintiff as a result of his persistent efforts to ....

vindicate his rights. - .'..’V . ‘

J- V . Nor is there any merit to defendants' contention that the ■

words "any*action or proceeding” in the statute mean only an action",

or proceeding in court. The plain meaning of the language indicates

quite to the'contrary. Had Congress wished to restrict an award of

an. attorney's fee to only suits filed in court, there would have

been no need to add the words "or proceeding" to "any ahtion." .But ■

"proceeding" is a broader term than "action” and would include an

administrative as well as a judicial proceeding. Moreover,- use of

the'words "under this subchapter" indicates the clear intention of :■

Congress to include the complementary administrative and judicial .;

enforcement proceedings provided for by §717(b) and (c) within .the

coverage of Subsection (k). .

In Parker v. Matthews, ____ F.Supp. ____, 44 tJ.S.L.W. 2496"-'

(D.D.C. April 1, 1976), the Court hold that a party who entered into

a settlement of her Title VII claim against the government was a •-

"prevailing party" under 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k). In awarding an

attorney's fee to the plaintiff, the Court said the following (page ;

10 of Memorandum Opinion):

" in Smith v. Kleindienst, 8 F.E.P. 753 (D.D.C. • >'•

•v 1973), aCC’d sub. nom. Smith v. I.evi, No. 74-1939,

\ . . (D.C.Cir. Dec. 2, 1975); an award of attorneys' .

fees included both the amount of time spent by . ' • 'ij>.

plaintiff’s attorneys on the administrative and • : ; •

?.•••*?' ■ the district court levels. In awarding a t t o r n e y s , . • , .

fees in Smith, supra, the Court, did not make a . •

distinction between the time spent during agency

proceedings and the time spent in court. The j

- t issue on appeal was simply whether the fee was

excessive, the Court holding that it was not.. v _

.. .<T. Accordingly, this Court will not make a distinc- .• 4 ,

... tion between the time spent by plaintiff’s attor

ney on the administrative and judicial levels.

'■ Plaintiff was forced to bring this action to the