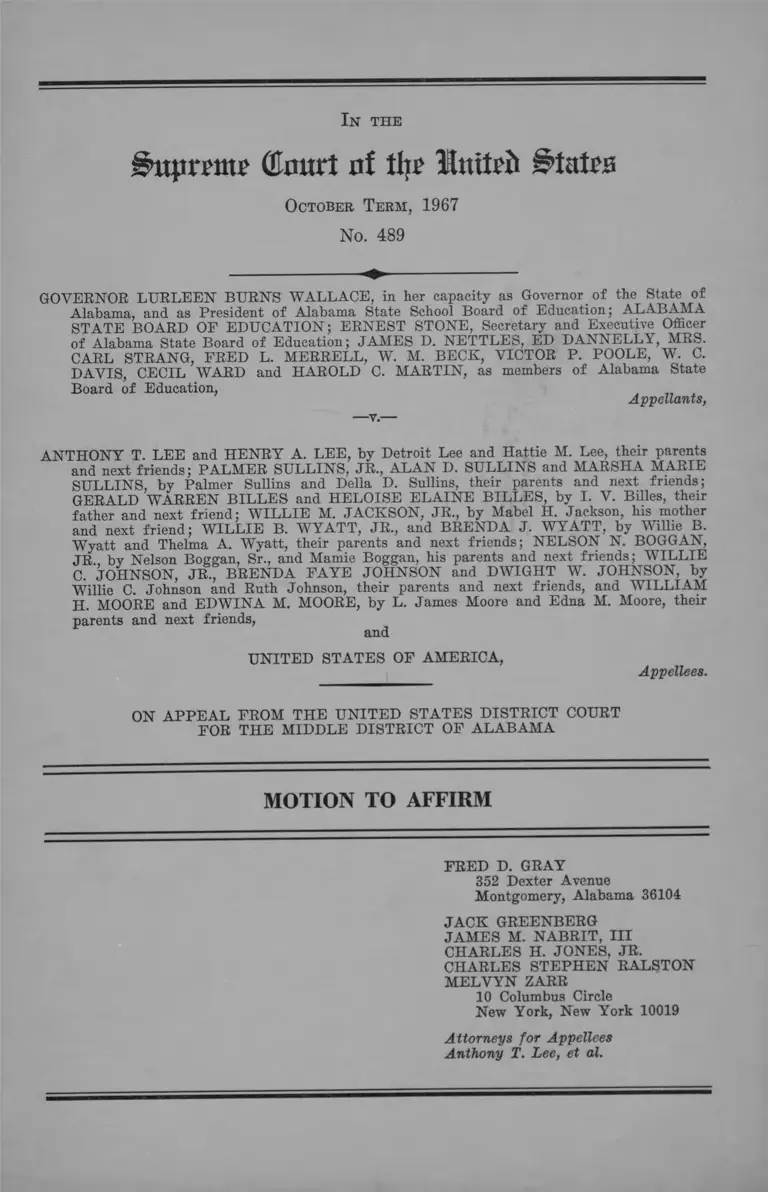

Wallace v. Lee Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wallace v. Lee Motion to Affirm, 1967. 24315b66-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8f325deb-eb93-40a1-bf4f-3e634cbbfcdd/wallace-v-lee-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

i&uprpm? fflmurt of tip' Itnitcit States

O cto ber T e r m , 1967

No. 489

In th e

GOVERNOR LURLEEN BURNS W ALLACE, in her capacity as Governor of the State of

Alabama, and as President of Alabama State School Board of Education; A LA B A M A

STATE BOARD OF ED UCATION ; ERNEST STONE, Secretary and Executive Officer

of Alabama State Board of Education; JAM ES D. NETTLES, ED D AN N ELLY, MRS.

CARL STRANG, FRED L. MERRELL, W . M. BECK, VICTOR P. POOLE, W . C.

D AVIS, CECIL W ARD and HAROLD C. M ARTIN, as members of Alabama State

Board of Education,

Appellants,

-v.-

AN TH O N Y T. LEE and H EN R Y A. LEE, by Detroit Lee and Hattie M. Lee, their parents

and next friends; PALMER SULLINS, JR., A L A N D. SULLINS and MARSHA M ARIE

SULLINS, by Palmer Sullins and Della D. Sullins, their parents and next friends;

GERALD W ARREN B ILLES and HELOISE E LAIN E BILLES, by I. V. Billes, their

father and next friend; W IL L IE M. JACKSON, JR., by Mabel H. Jackson, his mother

and next friend; W IL L IE B. W Y A T T , JR., and BRENDA J. W Y A T T , by Willie B.

Wyatt and Thelma A. Wyatt, their parents and next friends; NELSON N. BOGGAN,

JR., bv Nelson Boggan, Sr., and Mamie Boggan, his parents and next friends; W IL L IE

C. JOHNSON, JR., BRENDA F A Y E JOHNSON and DW IGHT W . JOHNSON, by

Willie C. Johnson and Ruth Johnson, their parents and next friends, and W IL L IA M

H. MOORE and E D W IN A M. MOORE, by L. James Moore and Edna M. Moore, their

parents and next friends,

and

U N ITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF A L A B A M A

MOTION TO AFFIRM

FRED D. GRAY

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

JACK GREENBERG

JAM ES M. NABRIT, II I

CHARLES H. JONES, JR.

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

M E L V YN ZARR

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

Anthony T. Lee, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ......................................... 2

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 2

Question Presented ........................................................... 2

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 3

A rgument

The Court Below Was Clearly Correct in Order

ing the Appellants to Implement the School De

segregation Decisions of This Court ....................... 9

A. The Court Below Correctly Appraised Ap

pellants’ Power Over Public Education in

Alabama and Correctly Found That That

Power Had Been Exercised to Thwart Rather

Than to Promote Desegregation ....................... 10

B. The Relief Fashioned by the Court Below

Represents a Measured and Carefully Con

sidered Judicial Response to Years of Foot-

Dragging and Defiance by State Officials Re

sponsible for School Desegregation in Ala

bama ................................................................. 12

Co n clu sio n ............................................................................ 15

11

T able of Cases

PAGE

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .... 9

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103

(1965) .............................................................................. 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .............................. 9

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960), cert,

den. 364 U. S. 933 (1961) .......................................... 9

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964) .................................. 9

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d, 368 U. S. 515 (1962) .... 9

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 221 F.

Supp. 297 (M. D. Ala. 1963) ..................................... 3

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 231 F.

Supp. 743 (M. D. Ala. 1964) .......................2,3,4,5,6,13

NAACP v. Wallace, 269 F. Supp. 346 (M. D. Ala.

1967) ................................................................................ 7

United States v. Rea, 231 F. Supp. 772 (M. D. Ala.

1964) ................................................................................ 3

United States v. Wallace, 222 F. Supp. 485 (M. D. Ala.

1963) ................................................................................ 3

Wallace v. Lee, 387 U. S. 916 (1967) ............................ 3

Ill

Statutes

page

28 U. S. C. §1253 ............................................................. 2

Code of Ala. Tit. 52, §61(8) ......................................... 9

Act No. 252, 1966 Special Session of the Alabama

Legislature ...................................................................... 6, 7

Act No. 266, 1967 Special Session of the Alabama

Legislature ...................................................................... 9

Act No. 285, 1967 Special Session of the Alabama

Legislature ...................................................................... 11

M iscellaneous

Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67 .... 10

. j

In the

Sntprmt (Emtrt of tip Unite State

O ctober T e r m , 1967

No. 489

G o v e r n o r L u r l e e n B u r n s W a l l a c e , in her capacity as Governor

of the State of Alabama, and as President of Alabama State

School Board of Education; A l a b a m a S t a t e B oard or E d u

c a t i o n ; E r n e s t S t o n e , Secretary and Executive Officer of

Alabama State Board of Education; J a m e s D . N e t t l e s , E d

D a n n e l l y , M r s . C a r l S t r a n g , F red L . M e r r e l l , W . M . B e c k ,

V icto r P . P o o le , W . C . D a v is , Ce c il W ard and H arold C.

M a r t in , as members of Alabama State Board of Education,

Appellants,

-v-

A n t h o n y T . L e e and H e n r y A. L e e , by Detroit Lee and Hattie

M. Lee, their parents and next friends; P a l m e r S u l l in s , J r .,

A t,a n D. S u l l in s and M a r s h a M ar ie S u l l in s , by Palmer

Sullins and Della D. Sullins, their parents and next friends;

G er a ld W a r r e n B il l e s and H elo ise E l a in e B il l e s , by I. V.

Billes, their father and next friend; W il l ie M. J a c k s o n , J r .,

by Mabel II. Jackson, his mother and next friend; AVil l ie B.

W y a t t , J r ., and B r e n d a J. W y a t t , by Willie B. AAryatt and

Thelma A. Wyatt, their parents and next friends; N e l s o n N.

B o g g a n , J r ., by Nelson Boggan, Sr., and Mamie Boggan, his

parents and next friends; AVil l ie C. J o h n s o n , J r ., B r e n d a

F a y e J o h n s o n and D w i g h t AV. J o h n s o n , by AVillie C. Johnson

and Ruth Johnson, their parents and next friends, and W il l ia m

II. M oore and E d w in a M. M oore , by L. James Moore and Edna

M. Moore, their parents and next friends,

and

U n it e d S t a t e s of A m e r ic a ,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

MOTION TO AFFIRM

2

Appellees Anthony T. Lee et al.1 respectfully move the

Court, pursuant to Eule 16(1) (c) of the Eules of the Court,

to affirm the judgment below, and in support thereof would

show that plenary consideration of this appeal is unneces

sary because the decision below is clearly correct.

Citations to Opinions Below

The decision below is reported at 267 F. Supp. 458 (M. D.

Ala. 1967). An earlier, highly relevant decision of the

court below in this case is reported at 231 F. Supp. 743

(M. D. Ala. 1964).

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this appeal is founded upon 28 U. S. C.

§1253, in that injunctive relief was sought and obtained

from a three-judge district court constituted pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §§2281, 2284 against the enforcement of a stat

ute of the State of Alabama on the ground of its federal

unconstitutionality.

Question Presented

Did the court below abuse its discretion in requiring ap

pellants to exercise their power over public education in

Alabama in such a way as to implement, rather than de

feat, the school desegregation decisions of this Court?

1 Appellees Lee et al. are the original plaintiffs in this ease. On

behalf of the class of all Negro schoolchildren in Alabama, they

filed the supplemental complaint and motion requesting the court

below to order the state-wide desegregation plan in issue here

(see 267 F. Supp. 458, 461-62). Thus they clearly are appellees

here, despite unfounded assertions to the contrary by appellants

in their jurisdictional statement (see pp. 7-8, 14, 45). In the in

3

Statement of the Case

This case originated in January, 1963 as a simple school

desegregation case brought by the appellees, Negro chil

dren and their parents residing in Macon County, Ala

bama.2 3 * After hearing, the district judge ordered the de

fendant school board to begin desegregation of the county

school system by September, 1963. Lee v. Macon County

Board of Education, 221 F. Supp. 297 (M. D. Ala. 1963).

In compliance with that order, the defendant school board

assigned 13 Negro students to a white high school. On Sep

tember 2, 1963, these Negro pupils were denied entrance

to the white high school by Alabama state troopers acting

pursuant to an executive order of Governor George C.

Wallace (see 231 F. Supp. at 747). Subsequently, on Sep

tember 9, 1963, state troopers again prevented entrance of

the Negro pupils to the white high school—again upon the

order of Governor Wallace (ibid.). The United States then

applied to the district court for injunctive relief against the

Governor, which was granted. United States v. Wallace, 222

F. Supp. 485 (M. D. Ala. 1963).

In January, 1964, the State Board of Education closed

the desegregated high school and transferred the Negro

students to an all-Negro high school (see 231 F. Supp. at

748). The district court then ordered that the Negro stu

dents be admitted to two all-white high schools (ibid.).8

stant appeal, appellees Lee et al. have heretofore filed an opposition

to appellants’ application for a stay pending appeal, Wallace v.

Lee, 387 U. S. 916 (1967).

2 In July, 1963, the United States Avas added as a party plaintiff

and as amicus curiae.

3 Official resistance to that order was enjoined in United States

v. Rea, 231 F. Supp. 772 (M. D. Ala. 1964).

4

In February, 1964, appellees filed a supplemental com

plaint, adding as defendants the Governor, the Executive

Officer and Secretary of the Alabama State Board of Edu

cation (also known as, and herein referred to as, the State

Superintendent of Education) and the other members of

the State Board of Education. In this supplemental com

plaint appellees requested the district court (1) to enjoin

these defendants from operating a dual school system based

upon race throughout the State of Alabama; (2) to enter

an order requiring state-wide desegregation of public

schools in the State of Alabama; (3) to enjoin the use of

state funds to perpetuate the dual school system and (4) to

enjoin as unconstitutional the tuition grant law of 1957

(Code of Ala., Title 52 §§61 (13)-61 (21)). Thereupon the

chief judge of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit,

in response to the request of the district judge, constituted

a three-judge court pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§2281, 2284

(231 F. Supp. at 746). The three-judge court continued in

effect, pending full hearing and determination, the tem

porary restraining order issued by the single district judge

enjoining the state officials from their various forms of

interference with the peaceful and orderly desegregation of

the public schools.

After extensive trial and briefing, the court rendered its

decision of July 13, 1964, 231 F. Supp. 743. The court

found interference by the state officials with local school

desegregation—and more. The court found that appellants

possessed “ general control and supervision over all the

public schools in the State of Alabama” and that these

powers were exercised to promote and maintain, rather

5

than to eliminate, segregation (231 F. Supp. at 756).4 The

court directed appellants to recognize that “ in the exercise

of their general control and supervision over all the public

schools in the State of Alabama and particularly in the allo

cation and distribution of state funds for school operations,

they have an affirmative duty to proceed with ‘deliberate

speed’ in bringing about the elimination of racial discrimi

nation in the public schools of this State” (231 F. Supp. at

756). Appellants were ordered “ to formulate and place

into effect plans designed to make the distribution of public

funds to the various schools throughout the State of Ala

bama only to those schools and school systems that have

proceeded with ‘deliberate speed’ in the desegregation of

their schools and school systems as required by Brown v.

Board of Education” (231 F. Supp. 756-57). But the court

withheld state-wide desegregation, preferring to rely for a

season upon the good faith of appellants (231 F. Supp. at

756):

For the present time, this Court will proceed upon the

assumption that the Governor, the State Superinten

dent of Education and the State Board of Education

will comply in good faith with the injunction of this

Court . . . and, through the exercise of considerable

judicial restraint, no state-wide desegregation will be

ordered at this time.

4 The Court found (231 F. Supp. at 750-51):

The evidence in this case is clear that over the years the

State Board of Education and the State Superintendent of

Education have established and enforced rules and policies

regarding the manner in which the city and county school

systems exercise their responsibilities under state law. This

control relates, among other things, to finances, accounting

practices, textbooks, transportation, school construction, and

even Bible reading.

6

Appellants were ordered to desist from interfering with

local desegregation attempts “— either directly or indirectly

—through the use of subtle coercion or outright interfer

ence” (231 F. Supp. at 756). Moreover, appellants were

enjoined from (order of July 13, 1964, paragraph 6):

Failing, in the exercise of its control and supervi

sion over the public schools of the State, to use such

control and supervision in such a manner as to pro

mote and encourage the elimination of racial discrimi

nation in the public schools, rather than to prevent and

discourage the elimination of such discrimination.

The court also concluded that Alabama’s tuition grant law

was nothing more than a sham established for the purpose

of financing with state funds a white school system in the

State of Alabama and enjoined its continued operation

(231 F. Supp. at 754). 2 £ 7

On September 1, 1965, a new tuition grant statute was

approved5 which was challenged by a supplemental com

plaint filed by the United States.6

On September 2, 1966, Act No. 252, 1966 Special Ses

sion, was approved, which purported to nullify the school

desegregation efforts by local public school officials pur

suant to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the

regulations and guidelines promulgated thereunder by the

United States Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare.7

5 Code of Ala. Tit. 52, §61(8).

6 The supplemental complaint was filed in August, 1966 and

alleged that the new tuition grant statute wras for no purpose

other than to perpetuate segregation in the public schools of

Alabama.

7 The Act provided, in relevant part: “Any agreement or assur

ance of compliance with the guidelines heretofore made or given

In September and November, 1966, appellees tiled an

additional supplemental complaint and a motion for further

relief challenging Act No. 252 and “ again asking for a

state-wide desegregation order and an injunction against

the use of state funds to support a dual school system”

(267 F. Supp. at 461-62). Following extensive discovery,

trial and briefing, the court rendered its decision on March

22, 1967, 267 F. Supp. 458.

The court’s opinion confirmed its earlier findings that

the appellants had enormous authority and power over the

actual operation of the various local school systems

throughout the state. “ This conclusion was based on the

actual assumption or usurpation of authority by these [ap

pellants] over the local school boards, exemplified by their

total control, when they chose to exert it, over the Macon

County school system, and also by the general statutory

power granted to these various officials to supervise and

control the public schools in the State of Alabama” (267

F. Supp. at 462).

The court found from the actions of appellants since July

13, 1964 that its reliance upon the good faith of the ap

pellants had been misplaced (267 F. Supp. at 465): “ Not

only have these [appellants], through their control and

influence over the local school boards, flouted every effort

to make the Fourteenth Amendment a meaningful reality

to Negro school children in Alabama; they have apparently

dedicated themselves and, certainly from the evidence in

this case, have committed the powers and resources of their

by a local, county or city board of education is null and void and

shall have no binding effect.” This Act was struck down in

NAACP v. Wallace, 269 F. Supp. 346 (M. D. Ala. 1967).

8

offices to the continuation of a dual public school system

such as that condemned by Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483.”

Therefore, the court concluded that an order granting

state-wide desegregation should no longer be withheld (267

F. Supp. at 465):

Based upon this fact and a continuation of such con

duct on the part of these state 'officials as hereafter

outlined, it is now evident that the reasons for this

Court’s reluctance to grant the relief to which these

plaintiffs were clearly entitled over two years ago

are no longer valid.

The court set forth in its opinion striking examples of

appellants’ actions constituting “ dramatic interference with

local efforts to desegregate public schools” (267 F. Supp.

462-470). But, the court concluded, “ the most significant

action by these [appellant] state officials, designed to main

tain the dual public school system based upon race, is found

in the day-to-day performance of their duties in the gen

eral supervision and operation of the system” (267 F. Supp.

at 470). The court then summarized the appellants’ “wide

range of activities to maintain segregated public educa

tion throughout the State of Alabama” (267 F. Supp. 470-

78). “ These activities have been concerned with and have

controlled virtually every aspect of public education in

the state, including site selection, construction, consolida

tion, assignment of teachers, allocation of funds, trans

portation, vocational education and the assignment of stu

dents” (267 F. Supp. at 478).

Because it could “ conceive of no other effective way to

give the [appellees] the relief to which they are entitled

9

under the evidence in this case” (267 F. Supp. at 478), the

court ordered a uniform state-wide plan for school desegre

gation.

The court also enjoined the 1965 version of the Alabama

tuition grant statute,8 finding that “ [i]t is clear that the

present tuition statute was born of the same effort to dis

criminate against Negroes, and was designed to fill the

vacuum left by this Court’s injunction against the 1957

tuition statute” (267 F. Supp. at 477).9

On May 22, 1967, this Court denied a stay of the district

court’s injunction, Wallace v. Lee, 387 U. S. 916.

A R G U M E N T

The Court Relow Was Clearly Correct in Ordering the

Appellants to Implement the School Desegregation Deci

sions of This Court.

The court below correctly concluded that this Court’s

school desegregation decisions10 would continue to have little

8 Code of Alabama, Title 52, §61(8) (Act No. 687, approved

September 1, 1965).

9 On August 31, 1967, appellant Wallace approved a new tuition

grant statute to fill the vacuum left by the court’s injunction in

issue here (Act No. 266).

10 See, e.g., Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955); Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958); HaU v. St. Helena. Parish School Board,

197 F. Supp. 649 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d, 368 U. S. 515 (1962) ;

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

U. S. 218 (1964); Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U. S.

103 (1965). See also Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir.

1960), cert. den. 364 U. S. 933 (1961).

10

meaning and effect in Alabama11 unless appellants were or

dered to apply the same ingenuity, effort and resources to

eradicate the dual school system in Alabama that they had

applied to create and maintain it. The court correctly ap

praised appellants’ power over public education in Ala

bama and fashioned a remedy adequate to reverse the

thrust of that power, requiring appellants to promote de

segregation rather than fight a rearguard action against it.

A. The Court Below Correctly Appraised Appellants’

Power Over Public Education in Alabama and Cor

rectly Found That That Power Had Been Exercised

to Thwart Rather Than to Promote Desegregation.

“ To maintain the racial characteristics of the Alabama

public school system, the [appellant] state officials have

used their power in essentially two ways. First, they have

used their authority as a threat and as a means of punish

ment to prevent local school officials from fulfilling their

constitutional obligation to desegregate schools, and, second,

they have performed their own functions in such a way as

to maintain and preserve the racial characteristics of the

system” (267 F. Supp. at 466).

The evidence as to appellants’ interference with local de

segregation attempts is overwhelming. The record is re

plete with outrageous examples of “ dramatic interference

with local efforts to desegregate public schools” (267 F.

Supp. at 470); a few are detailed in the court’s opinion,

267 F. Supp. 462-70. They reveal persistent pressure on

11 The extent o f school desegregation in Alabama has been piti

fully small. In the Fall of 1966, 95% of the state’s Negro pupils

were attending totally segregated schools. Report of the United

States Commission on Civil Rights, Southern School Desegregation,

1966-67, pp. 8-11.

11

local school officials to maintain segregation, including

threats to cut off state funds (see, e.g., Plaintiff’s Exhibit

11),12 to use the state police power (see 267 F. Supp. at 469)

and to expose local officials to public hostility (see Tran

script, pp. 61-62) and demands that the local officials resist

“ illegal” desegregation, that is, desegregation beyond the

minimum requirements of the federal courts (see 267 F.

Supp. at 467-68; see also Government’s Exhibits 6-11, 94;

Transcript, p. 33). Local officials who avoided desegrega

tion were rewarded with additional state funds (see 267

F. Supp. at 469-70; Government’s Exhibits 95-97; Defen

dants’ Exhibit 5).

But, the court found, “ the most significant action by these

[appellant] state officials, designed to maintain the dual

public school system based upon race, is found in the day-

to-day performance of their duties in the general super

vision and operation of the system” (267 F. Supp. at 470).

“ These activities have been concerned with and have con

trolled virtually every aspect of public education in the

state, including site selection, construction, consolidation

[see 267 F. Supp. at 470-72], assignment of teachers [see

267 F. Supp. at 472-73], allocation of founds [see 267 F.

Supp. at 469-70], transportation [see 267 F. Supp. at 473-

74], vocational education [see 267 F. Supp. at 474-75], and

the assignment of students” (267 F. Supp. at 478).

12 Subsequent to the court’s decision, on September 1, 1967, ap

pellant Wallace approved an Act (No. 285) requiring all students

to designate the race of their teacher and providing for the cut-off

of state funds to local school boards which did not require and

enforce those designations. On application by appellees, the three-

judge court bekm issued a temporary restraining order against

the Act’s enforcement on September 5, 1967.

12

B. The Relief Fashioned by the Court Below Represents

a Measured and Carefully Considered Judicial Re

sponse to Years of Foot-Dragging and Defiance by

State Officials Responsible for School Desegregation

in Alabama.

The court below acted on the principle that the equitable

remedy must be coextensive with the wrong suffered by

appellees and members of their class. Having examined

the wide range of appellants’ activities, see Part A, supra,

the court decided that “ [t]he remedy to which these [ap

pellees] are constitutionally entitled must be designed to

reach the limits of the [appellants’] activities in these sev

eral areas and must be designed to require the [appellants]

to do what they have been unwilling to do on their own—

to discharge their constitutional obligation to disestablish

in each of the local county and city school systems in Ala

bama that are not already operating under a United States

court order, the dual public school system to the extent

that it is based upon race or color” (267 F. Supp. at 478).

The court’s decree does just that (see 267 F. Supp. at

480-91).

Preliminarily, it should be noted that the decree is di

rected specifically and solely to the appellant state officials,

and not to local school boards. All the decree requires is

that the appellants use their undoubted power to imple

ment a state-wide desegregation plan.13

13 Appellants see a due process violation in the fact that the

local school boards were not made formal parties to the suit. This

contention was effectively dealt with by the court below (267 P.

Supp. at 479) :

The argument that this Court is proceeding without juris

diction over indispensable parties to this litigation, to-wit,

local school boards throughout the state, is not persuasive. We

are dealing here with state officials, and all we require at

13

The decree requires the appellants to exercise their clearly-

established powers, which heretofore have been used to

frustrate desegregation, to effectuate the disestablishment

of the dual school system in Alabama by taking the follow

ing actions (267 F. Supp. at 480-91):

1. To require that all local school boards not under court

desegregation order adopt uniform plans for desegregation

that meet minimum constitutional standards;

2. To plan school construction and consolidation so as

to promote desegregation;

3. To encourage and assist faculty desegregation;

4. To exercise their supervision over proposed school

bus routes so as to eliminate race as a basis for assigning

students to school buses and to eliminate overlapping and

duplicative bus routes based upon race;

this time is that those officials affirmatively exercise their con

trol and authority to implement a plan on a state-wide basis

designed to insure a reasonable attainment of equal educa

tional opportunities for all children in the state regardless

o f their race. It may be that in some instances a particular

school district will need to be brought directly into the liti

gation to insure that the defendant state officials have im

plemented this Court’s decree and that the state is not

supporting, financially or otherwise, a local system that is

being operated on an unconstitutional basis. Hopefully, these

instances will be the exception and not the rule. Clearly this

possibility does not diminish the propriety of the state-wide

relief to be ordered. Having already resolved this issue of

state-wide relief against the defendants in the order made and

entered in Lee, et al. (United States of America, Amicus

Curiae) v. Macon County Board of Education, July 13, 1964,

231 P. Supp. 743, further discussion and analysis is not

necessary.

14

5. To terminate all forms of segregation and discrimina

tion in all educational institutions under the direct control

of the State Board of Education, including trade schools,

junior colleges and state colleges;

6. To formulate a detailed program for equalizing Negro

schools with white schools;

7. To refrain from interfering with local officials in their

attempt to eliminate the dual school system; and,

8. To submit periodic detailed reports of their progress

to the court and to the parties.

Appellants urge the court to note probable jurisdiction

to eliminate “ the chaos now existing in the field of public

education” (Jurisdictional Statement, p. 59). Any chaos

which may exist in public education in Alabama is of the

appellants’ own making. It is they who have employed every

resource at their command to circumvent, and sometimes

defy, the school desegregation decisions of this Court.

When the appellants abandon the segregation policies which

they have imposed upon the State of Alabama, then local

school officials will “be able to return to the teaching of

students and dealing with the related educational problems

rather than expending their time and energies trying to

tread the difficult ‘middle ground’ between conflicting fed

eral and state demands” (267 F. Supp. at 478-79). To

hasten that day, the decision below should be affirmed.

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should

be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

F eed D. Gray

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles H. Jones, Jr.

Charles Stephen Ralston

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

Anthony T. Lee, et al.

• B MONTON STREET

NEW VONK >•*, N.U