Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1987. ea49bac4-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8f66bfc0-177c-456e-8129-dfdcb6311757/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

/

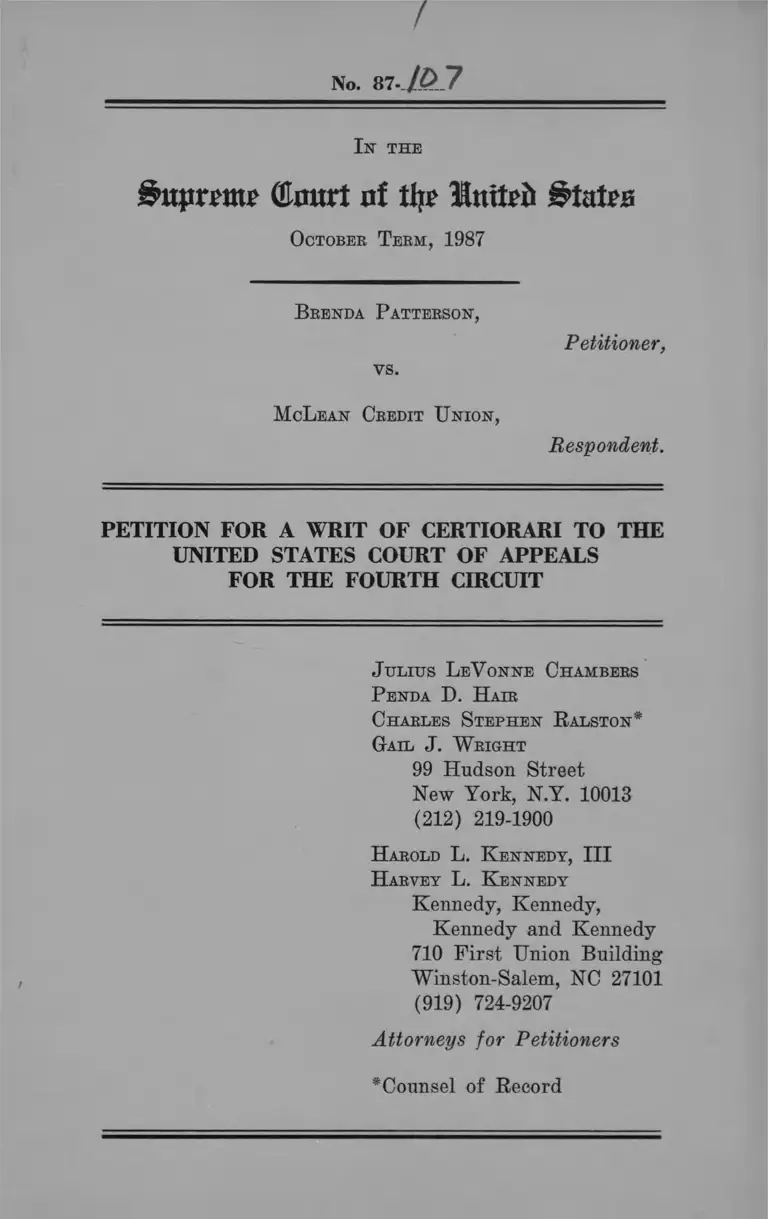

No. 87- M>7

I n the

&uprmp (Emtrt of % Ilmteii States

October Term, 1987

Brenda Patterson,

vs.

Petitioner,

M cL ean Credit U nion,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Julius L eV onne Chambers

Penda D. H air

Charles Stephen R alston*

Gail J. W right

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

H arold L. K ennedy, III

H arvey L. K ennedy

Kennedy, Kennedy,

Kennedy and Kennedy

710 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, NC 27101

(919) 724-9207

Attorneys for Petitioners

*Counsel o f Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does 42 U.S.C. § 1981 encompass

a claim of racial discrimination in the

terms and conditions of employment,

including a claim that petitioner was

harassed because of her race?

2. Did the district court err in

instructing the jury that in order for

petitioner to prevail on her claim of

discrimination in promotion that she must

prove that she was more qualified than

the white who received the promotion?

l

PARTIES IN THE COURT BELOW

All parties in this matter are set

forth in the caption.

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

iQUESTIONS PRESENTED

PARTIES IN THE COURT BELOW........ ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS................. iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............. V

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW ........ 1

JURISDICTION ....................... 2

STATUTE INVOLVED ................... 3

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .............. 3

1. Proceedings Below ........ 3

2. Statement of Facts........ 7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT . . . . 11

I. CERTIORARI SHOULD BE GRANTED

TO RESOLVE A CONFLICT BETWEEN

THE CIRCUITS AS TO WHETHER 42

U.S.C. § 1981 ENCOMPASSES

CLAIMS OF RACIAL HARASSMENT . . 13

II. THE DECISION BELOW IS INCON

SISTENT WITH DECISIONS OF THIS

COURT, INCLUDING GOODMAN V.

LUKENS STEEL CO. AND SHAARE

TEFILA CONGREGATION V. COBB . . 17

III. THE DECISION BELOW RELATING

TO BURDEN OF PROOF CONFLICTS

WITH DECISIONS OF THIS COURT

AND OTHER CIRCUITS............ 2 5

A. The Decision Below Con

flicts With Texas Dent, of

Corrections v. Burdine . . 25

iii

B. The Decision Below Is

In Conflict With

Decisions of Other

Circuits................ 29

CONCLUSION.........................34

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City,

717 F.2d 149 (4th Cir. 1983),

rev'd on other grounds. 470 U.S.

564 (1985) ...................

Block v. R. H. Macy & Co., Inc., 712

F.2d 1241 (8th Cir. 1983) . 12,

Carter v. Duncan-Huggins, Ltd., 727

F.2d 1225 (D.C. Cir. 1984) . . .

Christensen v. Equitable Life

Assurance, 767 F.2d 340

(7th Cir. 1985) ..............

Foster v. Areata Associates, Inc.,

772 F.2d 1453 (9th Cir. 1985) .

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 777

F.2d 113 (3rd Cir. 1985)

aff'd ___ U.S. ____, 55 U.S.L.

Week 4881 (1987) . . . . 16, 17,

Grano v. Department of Development

of the City of Columbus,

637 F.2d 1073 (6th Cir. 1980) .

Hamilton v. Rodgers, 791 F.2d 439

( 5th Cir. 1986) ............

Hawkins v. Anheuser-Busch, 697 F.2d

810 (8th Cir. 1983) . . 30, 31,

Hishon v. King & Spaulding, 467

U.S. 69 (1984) ..............

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

421 U.S. 454 (1975)............

Page

26

15

14

30

.30

25

31

14

32

19

21

• V

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U. S. 409 (1968)....... 22, 23, 24

Joshi v. Florida State University

Health Center, 763 F.2d 1227

(11th Cir. 1985)............ 32

Mitchell v. Baldrige, 759 F.2d 80

(D.C. Cir. 1985)............... 30

Ramsey v. American Air Filter

Company, 772 F.2d 1303

(7th Cir. 1985)............... 15

Shaare Tefila Congregation

V. Cobb, 481 U.S. ___, 95 L.Ed.

2d 594 (1987)............ 17, 25

Texas Dept, of Community

Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248 (1981)................. 26, 27

United States Postal Service

Board of Governors v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711 (1983) . . . . 31, 33

Wilmington v. J. I. Case Company,

793 F.2d 909 (8th Cir. 1986) 15, 16

Young v. Lehman, 748 F.2d 194

(4th Cir. 1984).............. 26

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1866 . . . . 22, 24

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).................3

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ............ 18, 22, 23

vi

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................... 14

Other Authorities:

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. 474 ................ 24

vii

NO. 87-

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1987

BRENDA PATTERSON,

Petitioner.

vs.

MCLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

The petitioner, Brenda Patterson,

respectfully prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on November 25, 1986.

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals

is reported at 805 F.2d 1143 and is set

2

out in the appendix to this petition at

pages la-20a. The order of the court of

appeals denying rehearing is set out in

the appendix hereto at pages 21a-22a.

The oral ruling of the district court

granting in part respondent's motion to

dismiss is unreported and is set out in

the appendix at pages 23a-25a. The

judgment of the district court dismissing

the case based on the jury's verdict is

set out in the appendix at pages 26a-28a.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals

affirming the Court's dismissal of the

case was entered on November 25, 1986.

App. la. The court of appeals entered an

order denying a timely petition for

rehearing en banc on March 19, 1987.

App. 22a. On June 5, 1987, Chief Justice

Rehnquist entered an order extending the

time for filing a petition for writ of

certiorari to and including July 17,

3

1987. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

This case involves 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

which provides:

All persons within the

jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same

right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties,

give evidence, and to the full

and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the

security of persons and

property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject

to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and

exactions of every kind, and to

no other.

(R. S. § 1977.)

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Proceedings Below

The petitioner, Brenda Patterson,

brought this action on January 25, 1984,

in the United States District Court for

the Middle District of North Carolina

against her former employer, McLean

Credit Union. The action was brought

4

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and alleged that

petitioner was discriminated against with

respect to promotions, layoffs, and in

the terms and conditions of employment,

including racial harassment. In

addition, the state tort claim of

intentional infliction of mental and

emotional distress was brought pursuant

to pendent jurisdiction.

The case was tried before a jury

from November 12 to November 18, 1985.

The trial court dismissed the claim of

racial harassment on the ground that 42

U.S.C. § 1981 did not provide a remedy

for racial harassment during the term of

employment.1 App. 23a-25a. With regard

to petitioner's claim that she was

discriminatorily denied promotional

opportunities, the district court

1The district court also did not

submit the state tort claim to the jury.

The correctness of that ruling is not

raised in this petition.

5

instructed the jury, over the objection

of the petitioner, that she had to prove

that she was more qualified for the

position than the person who received the

job.2 The jury returned a verdict in

favor of the defendant employer and the

district court dismissed the case in its

entirety. App. 26a-28a.

Petitioner appealed to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, which affirmed the district

court. The court of appeals held that

Section 1981 covered only racial

2Transcript of Trial, Nov. 18, 1985:

THE COURT: . . . the law in the

Fourth Circuit seems to be that in

order to make out a prima facie

case, you must show that you are

better qualified than the person who

received [the promotion], and I have

so instructed the jury.

MR. KENNEDY: I would like, for the

purposes of the record, to make an

exception to that point.

THE COURT: Yes, sir.

Id. at 5-30 - 5-31.

6

discrimination in hiring, firing and

promotion since those matters went to the

"very existence and nature of the

employment contract." App. 8a. The

court ruled that racial harassment

related to the terms and conditions of

employment and, therefore, did not,

standing alone, abridge the right to make

and enforce contracts that was conferred

by Section 1981. App. 9a.

With regard to the charge to the

jury, the court relied on prior Fourth

Circuit precedents requiring that a

plaintiff must prove that she was more

qualified than the person to whom the

promotion was given in order for her to

establish a prima facie case of

discrimination. Therefore, the instruc

tion was correct. App. 19a-20a.

A timely petition for rehearing and

suggestion for rehearing en banc was

denied. App. 21a-22a.

7

2. Statement of Facts

At trial, petitioner introduced

substantial evidence to support her claim

that she had been a victim of racial

harassment and had been treated

differently from similarly situated

whites in the terms and conditions of

employment. At the very beginning of her

employment she was told by the

defendant's president, Robert Stevenson,

that she would be working only with white

women and that those women would probably

not like her because they were not used

to working with blacks. Plaintiff was

never promoted; instead, after her

immediate supervisor spoke to the

president about petitioner's having too

heavy a work load, she was given more

work by Stevenson.^ Throughout her

employment she was given more work than

her white co-workers, and was then 3

3Tr. of Trial, pp. 1-86 - 1-87.

8

criticized for her alleged "slowness".

When she spoke to the president about her

work, she testified that he replied,

"Well, blacks are known to work slower

than whites by nature." He then added on

even more work.4 At staff meetings Mr.

Stevenson singled out plaintiff and the

other black worker by name and criticized

them for errors; white workers were not

subjected to this treatment.5 Finally,

Mr. Stevenson would stop by her desk and

stare at her four or five times a week,

making her nervous and unable to

concentrate on her work. Again, white

workers were not subjected to this

Id.. at 1-88 A white former

employee of defendant testified that Mr.

S t e v e n s o n had berated him for

recommending a black man for a computer

position. Mr. Stevenson told him that he

would not hire a Black because: "We

don't need any more problems around

here." Transcript of Trial, at p. 2-162.

5Id. at 1-89 - 1-90.

9

treatment.6

Plaintiff never was able to find out

about promotions that were available.7

White workers were trained for higher

level positions, while she was not.8 A

number of white employees were promoted

over her who had less education and

seniority, but who were given training.9

On July 19, 1982, plaintiff was laid off

and subsequently terminated; white

employees with less experience than her

were not.

A f t e r the p r e s e n t a t i o n of

plaintiff's evidence, the court dismissed

the claims of racial harassment and

intentional infliction of mental and

emotional distress. At the end of the

submission of all the evidence the trial

6Id. at 1-90 - 1-91.

7Id. at 1-91 - 1-92.

8Id. at 1-93.

9Id. at 1-93 - 1-97.

10

court instructed the jury that for

plaintiff to prevail on the promotion

claim she had to prove that she was more

qualified for the position of accountant

intermediate than was the white person

who was promoted.10 Plaintiff objected

10The district court charged, in

addition to instructing that plaintiff

had to have shown an interest in being

promoted and that a white person, Susan

Howard Williamson, was promoted instead, that:

In order to carry her burden [that

defendant denied her a promotion

because of her race], the plaintiff

must establish . . . (3) that

plaintiff was better qualified for

the position received by Susan

Howard Williamson than was Susan

Howard Williamson; and (4) that

plaintiff was denied the promotion

because of her race. (emphasis added).

With regard to the fourth

requirement, plaintiff offered

evidence tending to show that she

had not been trained for the job of

accountant intermediate because of

her race and was thus denied the

promotion because of her race.

Transcript of Trial, p. 5-12 -5-13.

The court later instructed that:

[I]t is necessary that [plaintiff]

11

to this part of the charge.11 The jury-

returned a verdict for the defendant

company.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This case presents an important

issue relating to the enforcement of the

civil rights statutes concerning which

the circuits are in conflict. The

availability of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 as a

remedy for harassment that is motivated

by racial animus is particularly

important because it is only under that

section that damages for such harassment

may be obtained. Title VII provides

satisfy you by a preponderance of

the evidence that she was more

qualified to receive the promotion

to the accountant intermediate

position than was Susan Howard

Williamson and that McLean's

intentional discrimination against

her because of her race was the real

reason that she did not receive the promotion.

Id. at 5-13 - 5-14.

11See n . 2, supra.

12

monetary relief only in the form of back

pay when, e.a. . a promotion has been

denied. Thus , in many cases of

harassment the only relief available

under Title VII will be an injunction

that simply reiterates the command of the

statute. Often, that relief will not be

a sufficient deterrent to harassment.

As the discussion that follows

demonstrates, the problem of racial

harassment and other discrimination in

the terms and conditions of employment is

persistent and recurring. Only the

threat of actual and punitive damages

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 can provide an

effective deterrent and help to rid the

work place of this most pernicious form

of discrimination.12

12See,_e.cf. . Block v. R. H. Macv &

Co. , Inc., 712 F. 2d 1241, 1243, 1245-48

(8th Cir. 1983) (Title VII and § 1981

claims for discharge and racial

harassment; $20,000 in actual and $60,000

in punitive damages awarded of which only

$7,598 was back pay under Title VII).

13

CERTIORARI SHOULD BE GRANTED TO RESOLVE A

CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CIRCUITS AS TO

WHETHER 42 U.S.C. § 1981 ENCOMPASSES

CLAIMS OF RACIAL HARASSMENT.

The court of appeals here held that

Section 1981 does not encompass racial

harassment on the reasoning that the

statute does not cover discrimination in

compensation, terms, conditions, or

privileges of employment. Rather it held

that § 1981 covers only matters that go

to the very existence and nature of the

employment contract, such as hiring,

firing and promotion. Four other courts

of appeals have ruled to the contrary and

have held that discrimination in the

terms and conditions of employment,

including racial harassment, violates

Section 1981.

The Fifth Circuit has ruled that an

offensive work environment caused by

racial harassment "would . . . establish

a successful case under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

I.

14

and 1983." Hamilton v. Rodgers, 791 F.2d

439, 442 (1986). Similarly, the District

of Columbia Circuit has concluded that

Section 1981 encompasses a claim that a

black plaintiff suffered "conduct and

conditions that were worse than those

imposed upon white employees." Carter v.

Duncan-Huggins. Ltd.. 727 F.2d 1225, 1233

(D.C. Cir. 1984) . The court explicitly

held that a pattern of differences in the

condition of employment, including the

telling of a racially derogatory joke,

can give rise to liability under Section

1981. Ibid. Therefore, it upheld

compensatory damages for humiliation and

other emotional harm resulting from "the

atmosphere of harassment." Id. at 1236,

1238-39.

Both the Seventh and Eighth Circuits

have also permitted recovery under

Section 1981 for emotional distress

caused by racial harassment in employment

15

where a defendant subjected a black

employee to different terms and

conditions of employment because of race.

These cases involved discriminatory job

assignments, discipline, and other forms

of racial harassment. Ramsev v. American

Air Filter Company. 772 F.2d 1303 (7th

Cir. 1985) ; Block v. R. H. Macv & Co. .

712 F.2d 1241 (8th Cir. 1983).13 See

also Wilmington v. J. I, Case Company.

793 F.2d 909 (8th Cir. 1986).14 And see.

13Although Block involved claims

under both Title VII and § 1981, racial

harassment was treated as an independent

cause of action under § 1981. The court

upheld the jury's damage award for

" m e n t a l anguish, h u m i l i a t i o n ,

embarrassment and stress," caused by such

harassment. 712 F.2d at 1245. Damages

for emotional distress are not

recoverable under Title VII.

14 The court in W i l m i n a t o n

specifically upheld an award of damages

for "emotional distress resulting from

the conditions under which folaintiffl

worked." 793 F.2d at 922. Although the

Court did not use the label "racial

harassment," the type of discrimination

at issue was the same as that involved in

the instant case. The plaintiff in

Wilmington was assigned to undesirable

16

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 777 F.2d 113

(3rd Cir. 1985), aff'd ___U.S. ___, 55

U.S.L. Week 4881 (1987) (affirming

finding of liability under § 1981 and

Title VII based in part on harassment of

black employees).

jobs so that he would not earn incentive

pay, 793 F. 2d at 915; plaintiff in the

instant case was given the undesirable

job of sweeping and dusting not required

of white clerical workers and was

assigned an exorbitant amount of work in

an attempt to force her to resign.

Plaintiff in Wilmington was repeatedly

verbally reprimanded, id. ; plaintiff in

this case was criticized in staff

meetings and subjected to racially

derogatory remarks. The defendant in

Wilmington moved the plaintiff's work

station closer to the foreman's office to

keep a close watch on him, id. ; in this

case, defendant's president stared at

plaintiff for several minutes several

times a week.

17

THE DECISION BELOW IS INCONSISTENT WITH

DECISIONS OF THIS COURT, INCLUDING

GOODMAN V. LUKENS STEEL CO. AND SHAARE

TEFILA CONGREGATION V. C O B B _______

Since the decision of the court

below this Court has indicated that

liability under both §§ 1981 and 1982,

parallel provisions of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, can be based on harassment

based on race. In Goodman v. Lukens

Steel Co. . _____ U.S. ____, 55 U.S.L.Week

4881 (1987) the Court affirmed findings

that § 1981 had been violated by, inter

alia. toleration by both an employer and

a union of racial harassment of black

employees. 55 U.S.L. Week at 4883. In

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb. 481

II.

U.S. , 95 L.Ed.2d 594 (1987) , the

Court reversed the Fourth Circuit and

held that claims by Jews that they had

been subject to harassment and vandalism

because of their ancestry stated a cause

18

of action under § 1982. Plaintiff urges

that these decisions directly support

their contention that discrimination in

the terms and conditions of employment is

prohibited by § 1981.

The conclusion that § 1981 prohibits

racial harassment in employment is

consistent with the language and purpose

of the statute. Section 1981 guarantees

to blacks "the same right . . . to make

and enforce contracts . . as is enjoyed

by white citizens," (emphasis added). A

contract is a combination of many "terms

and conditions." For example, a contract

to sell goods generally specifies the

nature and guantity of the goods, the

price, the method of payment, the method

of delivery and possibly other "terms and

conditions." A contract for employment

either explicitly or implicitly covers at

least the nature of the job, the salary,

the working hours, work rules, and

19

penalties for violations thereof, and the

location of the job. As this Court noted

in Hishon v. King & Spaulding. 467 U.S.

69, 74 (1984):

Because the underlying employment

relationship is contractual, it

follows that the "terms, conditions,

or privileges of employment" clearly

include benefits that are part of an

employment contract.

Despite these considerations, the

court below concluded that the only

element of the right to contract

protected by § 1981 is the right to

obtain employment under an unequal set of

conditions. Under the reasoning of the

court below, an employer that offered to

employ black individuals at a lower

salary than white individuals would not

violate § 1981, since black individuals

would not be totally deprived of the

right to contract for a job. This

analysis ignores § 1981's protection of

an equal right to contract.

The lower court's opinion does not

20

distinguish, and there is no basis for a

distinction, between explicit and

implicit conditions of a contract. Under

the court's decision, an employer could

say to black applicants: "I will hire

you if you agree that I may constantly

abuse you, give you the worse job

assignments and subject you to racially

derogatory remarks." Such a condition,

were it known at the outset of the

contractual relationship, would surely

discourage black individuals from

entering into an employment contract and

thus deprive them of an equal right to

make such contracts. The fact that these

terms and conditions of employment are

not stated at the outset and are not put

into a written document does not lead to

a different result. The employer's

actions establish that these are implicit

conditions of the contract which are

different for black employees than for

21

white employees, thus depriving black

employees of an equal right to make an

acceptable employment contract.

Section 1981's prohibition of

discrimination in all of the terms and

conditions of the employment contract was

made clear by this Court in Johnson v.

Railway Express Aaencv. 421 U.S. 454

(1975). The Court in Johnson found that

one of the purposes of § 1981 is to

"affor[d] a federal remedy against

discrimination in private employment on

the basis of race." Id. at 459-60. The

Court did not distinguish between hiring,

firing and promotion and other terms and

c o n d i t i o n s of the e m p l o y m e n t

relationship. In fact, the plaintiff's

claim in Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, was not about hiring, firing or

promotion, but rather discrimination in

other terms and conditions of his

employment — seniority rules and job

22

assignments. Id. at 455.

The legislative history of § 1981

also supports coverage of terms and

conditions of the employment contract,

including work environment and racial

harassment. Section 1981 was first

enacted as part of § 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866. The legislative

history and purpose of § 1 was analyzed

in detail by this Court in Jones v.

Alfred H, Maver Co. . 392 U.S. 409

(1968).15 The Court in Jones v. Maver

repeatedly emphasized that the 1866 Act

was "cast in sweeping terms" in order "to

prohibit all racially motivated

deprivations of the rights enumerated in

15The provision of the 1866 Act at

issue in Jones v. Alfred H. Maver Co. has

been codified as 42 U.S.C. § 1982. In

language parallel to that of § 1981,

§ 1982 guarantees "the same right . . .

as is enjoyed by white citizens . . . to

inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and

convey real and personal property." See 392 U.S. at 441, n. 78.

23

the statute." Id. at 422, 426.16 This

Court relied on legislative history that

Congress "believed that it was approving

a comprehensive statute forbidding all

racial discrimination affecting the basic

civil rights enumerated in the Act." Id.

at 435 (emphasis added). See also id. at

436.

In addressing the meaning of § 1982,

the parallel provision to § 1981 that

guarantees equal rights to sell and lease

property, the Court held that the 1866

Act conferred "'the right . . . to

purchase . . . real estate . . . without

any qualification and without any

restriction whatever . . . . '" Id. at

43 5 (emphasis added) (quoting Cong.

Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. at 1781

(Senator Cowan)). Thus, the Court ruled

that § 1982 prohibited all racial

16See also 392 U.S. at 431 ("sweeping

and e f f i c i e n t " ) ; i d . at 4 3 3

("sweeping . . . effect").

24

discrimination in the sale and rental of

property. Id. at 436-437 •

The Court also stressed that the

1866 Act was intended to give "real

content" and "practical" meaning to the

guarantees of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Id. at 427, 431 (quoting Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474 (Senator

Trumbull))17 Thus, the Act was intended

to eliminate the "'private outrage and

atrocity'" that were "'daily inflicted on

freedmen.'" Id. at 427.

The panel decision's restrictive

construction of § 1981 is inconsistent

with this legislative history. Congress'

desire to prohibit "all racial

discrimination affecting" the ability to

make and enforce contracts clearly

encompasses racial harassment which

interferes with enjoyment of the benefits

of the contract. Congress' desire to

17See also 392 U.S. at 434.

25

provide "practical" freedom of contract

and to prevent oppression of black

citizens would be rendered meaningless if

an employer could, through harassment,

deprive black employees of a work

experience equal to that of white

employees.

In light of these considerations it

would be appropriate to vacate the

decision of the Fourth Circuit and to

remand for further consideration in light

of this Court's recent decisions in

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co. and Shaare

Tefila Congregation v. Cobb.

III.

THE DECISION BELOW RELATING TO BURDEN OF

PROOF CONFLICTS WITH DECISIONS OF THIS

COURT AND OTHER CIRCUITS.

A. The Decision Below Conflicts With

Texas Dept. of Corrections v.

Burdine.

As described above, the district

court, over plaintiff's objection,

instructed the jury that in order for the

26

plaintiff to prevail on her dis

crimination in promotion claim she must

prove that she was better qualified for

the position than was the white employee

who received it. Indeed, the district

court further instructed the jury that

plaintiff must prove both that she was

more qualified and that the employer's

intentional discrimination against her

because of her race was "the real reason"

that she was not promoted.

These instructions, and the line of

cases in the Fourth Circuit upon which

they were based,18 are in conflict with

the holdings of this Court and with other

circuits. The Fourth Circuit's rule

squarely conflicts with this Court's

decision in Texas Dept. of Community

Affairs v. Burdine. 450 U.S. 248, 259

18Younq v. Lehman 748 F.2d 194 (4th

Cir. 1984); Anderson v. City of Bessemer

City. 717 F.2d 149 (4th Cir. 1983), rev'd

on other grounds. 470 U.S. 564 (1985).

27

(1981) . There, it was held that an

"employer has discretion to chose among

equally qualified candidates "provided

that the decision is not based upon

unlawful criteria." (Emphasis added.)

Admittedly, the mere fact that an

employer has chosen a white when there

were two equally qualified candidates

does not by itself establish dis

crimination. However, Burdine makes it

clear that discrimination can be

established absent proof that the Black

was better qualified.

To give an example, assume that the

selecting official testified that the

white and black candidates were equally

qualified and therefore he picked the

white person because he thought a white

would fit in better with an all-white

work force. Such testimony would

establish beyond question a violation of

§ 1981. Nevertheless, under the district

28

court's instruction, the jury here would

have been required to find for the

employer.

The import of the instruction is to

focus the jurors' inquiry entirely on the

question of relative qualifications to

the exclusion of other evidence from

which a finding of discrimination could

be inferred. Petitioner introduced

substantial evidence that she had been

subjected to racially derogatory remarks,

had been discriminatorily denied

training, and had been harassed because

of her race. This evidence would amply

support an inference that petitioner had

been discriminated against and was denied

the promotion irrespective of her

qualifications or those of her white co

worker. However, once the jurors had

decided that petitioner had not

demonstrated superior qualifications, the

court's instructions would necessarily

29

lead them to ignore the other evidence

that petitioner had been subjected to

disparate treatment.

B. The Decision Below Is In Conflict

With Decisions Of Other Circuits.

In explaining the instruction given

to the jury the district court stated:

"The law in the Fourth Circuit seems to

be that in order to make out a prima

facie case you must show that you are

better qualified than the person who

received the promotion.1,19 The court of

appeals upheld this instruction on the

ground that where the reason given in

rebuttal to justify an action by the

employer was the relative qualifications

of the blacks and white applicants, then

the plaintiff has the burden of proving

that her qualifications are superior.

Both holdings are in conflict with

decisions of other circuits. First.

19See n. 2, supra.

30

there is substantial agreement among the

other courts of appeals that a plaintiff

need only establish that she was

qualified for the position in order to

make out a prima facie case, and not that

she had superior qualifications. In

Mitchell v. Baldriqe. 759 F.2d 80 (D.C.

Cir. 1985), the court vacated the

dismissal of the plaintiff's case when a

district court required that the

plaintiff demonstrate that she was at

least as qualified as the person chosen.

The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits

have similarly held that an employee need

only show that he or she was qualified

for the position at issue in order to

establish a prima facie case. See.

Christensen v. Equitable Life Assurance

Soc. . 767 F. 2d 340, 342-343 (7th Cir.

1985) ; Hawkins v. Anheuser-Busch. Inc. .

697 F. 2d 810 (8th Cir. 1983) ; Foster v.

Areata Associates. Inc.. 772 F.2d 1453,

31

1460 (9th Cir. 1985). See also Grano v.

Department of Development of the City of

Columbus. 637 F.2d 1073, 1079 (6th Cir.

1980).

Second, although in the present case

the trial went beyond the stage of

proving a prima facie case (see, United

States Postal Service Board of Governors

v. Aikens. 460 U.S. 711 (1983)), the

approval by the Fourth Circuit of the

instruction is in conflict with the law

of two other circuits. Thus, in Hawkins

v. Anheuser-Busch. Inc.. 697 F.2d at 813-

15, the Eighth Circuit held that although

the defendant had rebutted the prima

facie case by articulating the selectees'

superior qualifications, the explanation

was shown to be a pretext because the

plaintiff proved that she was at least as

qualified for the position. Thus, under

Hawkins. in the appropriate circumstances

a showing of equal qualifications would

32

be sufficient to prove the Title VII

claim because it would demonstrate the

pretextual nature of the proffered

explanation.

Similarly, in Joshi v. Florida State

University Health Center. 763 F.2d 1227,

1235 (11th Cir. 1985), the Eleventh

Circuit held that the relative

qualifications of the persons hired could

not be the reason for the defendant's

failure to hire the plaintiff since she

was not actively considered for the

position. Here also there was ample

evidence from which a properly instructed

jury could have found that plaintiff had

never been seriously considered for the

promotion and had been prevented from

being so because of a discriminatory

denial of training. Such a conclusion

was foreclosed by the district court's

instruction that the plaintiff could not

win unless she proved that she was more

33

qualified than the selectee.

In summary, the district court's

instruction that proof of superior

qualifications was an absolute

requirement for the plaintiff's case

conflicts with the law in five other

circuits. The issue of the question of

relative qualifications is a recurring

one in the lower courts. See United

States Postal Service v. Aikens. 460 U.S.

at 713. Given both the conflict in

circuits and the recurrence and

importance of the issue, certiorari

should be granted to resolve it in the

present case.

34

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons certiorari

should be granted and the decision of the

court below reversed.

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

PENDA D. HAIR

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON*

GAIL J. WRIGHT

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

HAROLD L. KENNEDY, III

HARVEY L. KENNEDY

Kennedy, Kennedy,

Kennedy and Kennedy

710 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, NC 27101

(919) 724-9207

Attorneys for Petitioners

♦Counsel of Record

A P P E N D I X

la

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 85-2394

Brenda Patterson,

Appellant,

versus

McLean Credit Union,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina, at Winston-Salem. Hiram H.

Ward, Chief District Judge. (84-0073)

Argued October 9, 1986. Decided November

25, 1986

Before WIDENER and PHILLIPS, Circuit

Judges, and HAYNSWORTH, Senior Circuit

Judge.

2a

Harold L. Kennedy, III; Harvey L. Kennedy

(Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy and Kennedy on

brief) for Appellant; H. Lee Davis, Jr.

(George E. Doughton, Jr.; Hutchins

Tyndall, Doughton and Moore on brief for

Appellee.

PHILLIPS, Circuit Judge:

In this action the plaintiff, Brenda

Patterson, sued her employer, McLean

Credit Union (McLean), on claims, under

42 U.S.C. § 1981, of racial harassment,

and failure to promote and discharge,

together with a pendent state claim for

intentional infliction of mental and

emotional distress.* The district court

submitted the § 1981 discharge and pro

motion claims to the jury which returned

a verdict in favor of McLean, and granted

* Presumably for statute of limitations

reasons, Patterson did not assert a claim

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000(e), et seq.

3a

directed verdicts to McLean on the § 1981

racial harassment claim and on the pen

dent state claim for intentional inflic

tion of mental and emotional distress.

We hold that the claim for racial harass

ment was not cognizable under 1981; that

the evidence was insufficient to support

the pendent state claim; and that the

court did not err in its jury instruc

tions nor in its evidentiary rulings on

the submitted claims under 1981. We

therefore affirm.

I.

Brenda Patterson, a black woman, was

an employee of McLean Credit Union from

May 5, 1972 to July 19, 1982, when she

was laid off. Robert Stevenson, McLean's

president, hired Patterson to be a teller

and file coordinator. According to Pat

terson's testimony, when he hired her,

4a

Stevenson told Patterson that the other

women in the office, who were white,

probably would not like her because she

was black. During her ten years of em

ployment with McLean, Patterson expe

rienced treatment that she considered to

be racially motivated harassment by

Stevenson. She testified that he

periodically stared at her for several

minutes at a time; that he gave her too

many tasks, causing her to complain that

she was under too much pressure; that

among the tasks given her were sweeping

and dusting, jobs not given to white

employees. On one occasion, she testi

fied, Stevenson told Patterson that

blacks are known to work slower than

whites. According to Patterson,

Stevenson also criticized her in staff

meetings while not similarly criticizing

5a

white employees.

Patterson never was promoted from

her position as teller and file coor

dinator throughout her tenure at McLean.

Susan Williamson, a white employee who

was hired by McLean in 1974 as an ac

counting clerk, received a title change

from "Account Junior" to "Account Inter

mediate" in 1982. This title change

entailed no change of responsibility.

Patterson asserted that Williamson's

title change was a promotion that Patter

son herself should have received, based

primarily on her seniority over William

son. Patterson also claimed that her

1982 layoff was discriminatory because

white employees with less experience kept

their jobs.

Patterson based her § 1981 claims

and her state claim of intentional

6a

infliction of mental and emotional

distress on the evidence above summar

ized. The district court held that a

claim for racial harassment is not cog

nizable under § 1981, and refused to

submit that claim to the jury. Examining

North Carolina case law applicable to

Patterson's pendent state claim, the

district court concluded that Stevenson's

treatment of Patterson did not rise to

the level of outrageousness reguired

under state law for recovery for inten

tional infliction of emotional distress

and directed a verdict against Patterson

on that claim. The court submitted the

1981 claims for discriminatory failure to

promote and discharge to the jury, which

returned a verdict for McLean. This

appeal followed.

7a

Patterson first challenges the

court's refusal to submit her related

claims for racial harassment and inten

tional infliction of mental and emotional

distress to the jury.

A.

We hold, in agreement with the dis

trict court, that Patterson's claim for

racial harassment is not cognizable under

§ 1981, which provides in relevant part

that "[a]11 persons within the jurisdic

tion of the United States shall have the

same right . . . to make and enforce con

tracts ... as is enjoyed by white citi

zens." That racial harassment claims are

cognizable under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000(e),

does not persuade us otherwise. The

broader language of Title VII, which

II.

8a

makes unlawful "discriminat[ion] against

any individual with respect to his com

pensation, terms, conditions f or privi

leges of employment because of such

individual's race," 42 U.S.C. § 2000

(e)(2)(a) (emphasis added), stands in

critical contrast to § 1981's more narrow

prohibition of discrimination in the

making and enforcing of contracts. cf.

United— States v. Buffalo, 457 F. Supp.

612, 631 (W.D.N.Y. 1 9 7 8 ) (the

intentionally broad provisions of Title

V I I accommodate claims based on having to

work in a racially discriminatory

environment), modified on other grounds.

633 F.2d 643 (2d Cir. 1980). Claims of

racially discriminatory hiring, firing,

and promotion go to the very existence

and nature of the employment contract and

thus fall easily within § 1981's protec

9a

tion. Instances of racial harassment, on

the other hand, may implicate the terms

and conditions of employment under Title

VII, see e.q. . EEOC v. Murphy Motor

Freight, 488 F. Supp. 381, 384-86 (D.

Minn. 1980), and of course may be proba

tive of the discriminatory intent re

quired to be shown in a § 1981 action,

see e.g., Carter v. Duncan-Huggins, Ltd..

727 F. 2d 1225, 1233 (D.C. Cir. 1984),

but, standing alone, racial harassment

does not abridge the "right to make" and

"enforce" contracts - including personal

service contracts - conferred by § 1981.

The cases relied on by Patterson are

not to the contrary. None directly holds

that racial harassment gives rise to a

discrete claim under § 1981, as distin

guished from recognizing that racial

harassment may be relevant as evidence of

- ioa

discriminatory intent supporting a cog

nizable claim of employment discrimina

tion under § 1981 and that it may give

rise to a discrete Title VII claim. See

Murohv Motor Freight. 488 F. Supp. at

384 (Title VII claim for racial harass

ment) ; Buffalo. 457 F. Supp. at 632-35,

636-37 (discriminatory work environment

claim under Title VII; 1981 claims of

discriminatory assignment and termina

tion) . But cf. Goodman v Lukens Steel

Co. . 580 F. Supp. 1114, 1164 (E.D. Pa.

1984)(very generally citing § 1981, along

with Title VII, as a basis for a claim of

racial harassment) Croker v. Boeing Co. .

437 F. Supp. 1138, 1191-92, 1193-94,

1195, 1198 (E.D. Pa. 1977)(discussing

racial harassment claim only under Title

VII, but indicating liability based upon

both Title VII and § 1981 in order) ,

12a

of McLean's conduct did not rise to the

level of outrageousness and extremity-

required by the North Carolina courts to

allow recovery under this cause of

action. We agree with this assessment.

The standard of "outrageousness" estab

lished in the relatively few state court

decisions is understandably a stringent

one. Recovery under that standard has

been permitted only for conduct far more

egregious than any charged to McLean in

Patterson's evidence.

For example, in Woodruff v. Miller.

307 S . Ed. 2d 187, 178 (N.C. App. 1983),

recovery was permitted where a defendant

had employed what the court characterized

as "truculent, vindictive methods"

inspired by a "consuming animus against

plaintiff" to circulate a thirty year old

record of plaintiff's" nolo contendere

11a

modified on other grounds. 662 F.2d 975

(3d Cir. 1981) .

We therefore affirm the district

court's grant of directed verdict in

Patterson's claim of racial harassment

under § 1981.

B.

We also agree with the district

court that Patterson's evidence was not

sufficient to support submission of her

pendent state claim of intentional in

fliction of mental and emotional dis

tress. The essential elements of such a

claim under North Carolina law are (1)

extreme, outrageous conduct, (2) intended

to cause and causing (3) severe emotional

distress. E.g.. Dickens v. Purvear. 276

S .Ed. 2d 325, 335 (N.C. 1981). The dis

trict court ruled that given its most

favorable reading, Patterson's evidence

13a

plea to a criminal charge, had compared

plaintiff to dangerous fugitives, and had

taken open delight in plaintiff's

resulting mental disturbance.

In Dickens, recovery was permitted

against a defendant who had assaulted

plaintiff and threatened to kill him

unless he left the state.

Of particular relevance is Hogan v.

Forsyth Country Club Co.. 340 S.E.2d 116

(N.C. App. 1986), in which one of three

female plaintiffs recovered for inten

tional infliction of emotional distress

when a fellow employee of her employer-

defendant screamed and shouted at her,

engaged in non-consensual and intimate

sexual touching, made sexual remarks, and

threatened her with a knife. Signifi

cantly, the two other plaintiffs were

denied recovery though the same fellow

14a

employee had screamed, shouted, and

thrown a menu at one of them and had

given strenuous work to and denied the

request of another, who was pregnant, to

leave work when she thought she was in

labor.

Evaluated in light of the stringent

standard established by these decisions,

the conduct of McLean through its presi

dent, Stevenson, was not "extreme and

outrageous." That Stevenson stared at

Patterson often, gave her too much work,

required her to sweep and dust, and com

mented that blacks are slower than whites

are facts that, though patently unworthy

if true, fall far short of those in any

North Carolina decision finding "extreme

and outrageous" conduct under this state

tort cause of action.

15a

We therefore affirm the district

courts grant of directed verdict on this

claim.

III.

Patterson next challenges the ex

clusion of proffered testimony by two

witnesses in support of her submitted

claims of employment discrimination under

§ 1981 and a jury instruction respecting

claimant's burden of proof on her promo

tion claim.

Marie Roseboro was tendered as an

expert in personnel administration and

would have given an opinion that Patter

son was better qualified than Susan

Williamson for the "promotion" given the

latter. The district court refused to

admit this proffered testimony on the

basis that it did not meet the require

ment of Fed. R. Evid. 702 that expert

16a

testimony be helpful to the trier of

fact.

The court also excluded the lay

testimony of another black women formerly

employed by McLean, Anita Reid Stovall,

to the effect that she had experienced

harassment by Stevenson during her em

ployment in 1972. The court ruled this

testimony inadmissible under Fed. R.

Evid. 403, finding its probative value on

the issue of discriminatory intent out

weighed by its remoteness in time and its

potential to confuse and mislead the

jury.

There was no abuse of discretion in

the trial court's decision to exclude the

testimony of these two tendered wit

nesses. Because of the remoteness in

time of the events to which Stovall would

have testified, the probative value of

17a

that evidence would have been slight and

the court could properly conclude that

its slight value was outweighed by the

likelihood of confusion it might create

on the issue on which it was tendered.

See Fed. R. Evid. 403.

The district court also could prop

erly conclude that Roseboro's proffered

testimony regarding the relative qualifi

cations of Patterson and other McLean

employees would not be helpful to the

jury so as to justify its admission as

expert opinion under Red. R. Evid. 702.

The trial court's conclusion that the

jury needed no aid in making a finding on

the relative qualifications of clerical

employees at a credit union, a comparison

that is not a highly technical or compli

cated one, was not an abuse of its dis

cretion.

18a

Finally, Patterson complains that

the trial court erroneously instructed

the jury that in order for her to prevail

on her promotion discrimination claim,

she had to show that she was more quali

fied than Susan Williamson. There was no

error in the instruction given.

An employee claiming race discrimi

nation in employment decision sunder §

1981 must prove intentional discrimina

tion. Such a claim is therefore compara

ble to the individual disparate treatment

claim under Title VII. The disparate

treatment proof scheme developed for

Title VII actions in McDonnell Douglas

Coro, v. Green. 411 U.S. 792 (1973) and

its progeny, may properly be transposed,

as here, to the jury trial of a § 1981

IV

claim. See Carter. 727 F.2d at 1232.

19a

Under that scheme, once an employer had

advanced superior qualification as a

legitimate nondiscriminatory reason for

favoring another employee over the

claimant, the burden of persuasion is

upon the claimant to satisfy the trier of

fact that the employer's proffered reason

is pretextual, that race discrimination

is the real reason.

That was the situation here, and the

district court therefore properly in

structed the jury that the burden was

upon the claimant to prove her superior

qualifications by way of proving race

discrimination as the effective cause of

the denial to her of "promotion." See

Young v. Lehman. 748 F.2d 194, 197-98

(4th Cir. 1984) ; see also Loeb v. Text

ron. Inc.. 600 F.2d 1003, 1010, 1016 (1st

Cir. 1979)(effect on jury instructions of

20a

transposing McDonnell Douglas proof

scheme to jury trial of ADEA claim) .

This simply reflects the principle

established in Title VII cases that an

employer may, without illegally discrimi

nating, choose among equally qualified

employees notwithstanding some may be

members of a protected minority. See

Anderson v. City of Bessemer Citv. 717

F. 2d 149, 154 (4th Cir. 1983), rev'd on

other grounds. 470 U.S. 564 (1985).

The court's instructions here were

therefore proper.

AFFIRMED

21a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-2394

BRENDA PATTERSON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

versus

MCLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Defendant-Appellee.

O R D E R

There having been no request for a

poll of the court on the petition for

rehearing en banc, it is accordingly

ADJUDGED and ORDERED that the petition

for rehearing en banc shall be, and it

hereby is, denied.

The panel has considered the

22a

petition for rehearing and the response

thereto and is of opinion the petition is

without merit.

It is accordingly ADJUDGED and

ORDERED that the petition for rehearing

shall be, and it hereby is, denied.

With the concurrences of Judge

Phillips and Judge Haynsworth.

/s/ H. E. Widener, Jr.

For the Court

Filed: March 19, 1987.

23a

ORAL RULING OF DISTRICT COURT

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WINSTON-SALEM DIVISION

BRENDA PATTERSON, ) CIVIL ACTION NO.

Plaintiff ) C-84-73-WS

)vs. )

)MCLEAN CREDIT UNION, )

Defendant )

.......................)

TRANSCRIPT OF TRIAL

BEFORE THE HONORABLE HIRAM H. WARD, and a

jury

Vol. 3 of 5

* * *

MR. KENNEDY: Your Honor, I'd like

to address, if I could, that one claim

that — it was assumed in the other two

claims — but really, under the law,

racial harassment or failure to have a

working environment free of racial

prejudice is a separate thing.

24a

THE COURT: Yes, I understand

that, and this is a 1981 case — and if

the jury finds a history of racial

harassment which culminated in failure to

promote and discharge of the plaintiff,

they can take that into consideration.

But it is not a separate claim under

Title — under Section 1981, in my

opinion, in the context of this case.

MR. KENNEDY: We cited some cases

similar to the case at bar here in our

brief —

THE COURT: Yes, sir, they are all

Title VII cases, aren't they?

MR. KENNEDY: But, Your Honor, that,

to me, when I look at —

THE COURT: Well, it isn't to me,

and I've already ruled on it, so that's

the way its going to go. I'm going to

let the promotional claim go to the jury,

25a

and I'm going to let the layoff and

subsequent termination claim go to the

jury, and I'm dismissing the rest of the

claims.

(Pages 3-75-3-76.)

26a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WINSTON-SALEM DIVISION

BRENDA PATTERSON,

Plaintiff

v.

MCLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Defendant

C—84-73—WS

J U D G M E N T

This case came on for trial before

the Court and a jury on November 12-18,

/■1985, and the issues having been duly

tried and answered by the jury as

follows:

1. Did defendant unlawfully

discriminate against plaintiff because of

her race, in violation of 42 U.S.C. §

1981:

27a

a. by denying plaintiff a

promotion received by

Susan Howard Williamson?

Answer: ________No___________

(Yes or No)

b. by laying off plaintiff on

July 19, 1982 and subse

quently discharging plain

tiff?

Answer: _______ No______________

(Yes or No)

2. If defendant did unlawfully

discriminate against plaintiff, what

amount of compensatory damages, if any,

is plaintiff entitled to recover:

a. for defendant's denying

plaintiff a promotion

received by Susan Howard

Williamson?

Answer: ______________________(Amount)

b. for defendant's laying off

28a

plaintiff on July 19, 1982

and subsequently dischar

ging plaintiff?

Answer: _______________________

(Amount)

3. If plaintiff was discriminated

against in her employment because of her

race, and the defendant's actions in so

doing were malicious, wanton, or oppres

sive, what amount of punitive damages, if

any, is plaintiff entitled to recover

from defendant?

Answer: _______________________(Amount)

IT IS, THEREFORE, ORDERED, ADJUDGED

AND DECREED that the plaintiff have and

recover nothing on her claims against the

defendant and that this action be, and

the same hereby is, DISMISSED.

s/------------------------------United States District Judge

November 20, 1985.

Hamilton Graphics/ Inc.— 200 Hudson Street/ New York/ N.Y.— (212) 966-4177