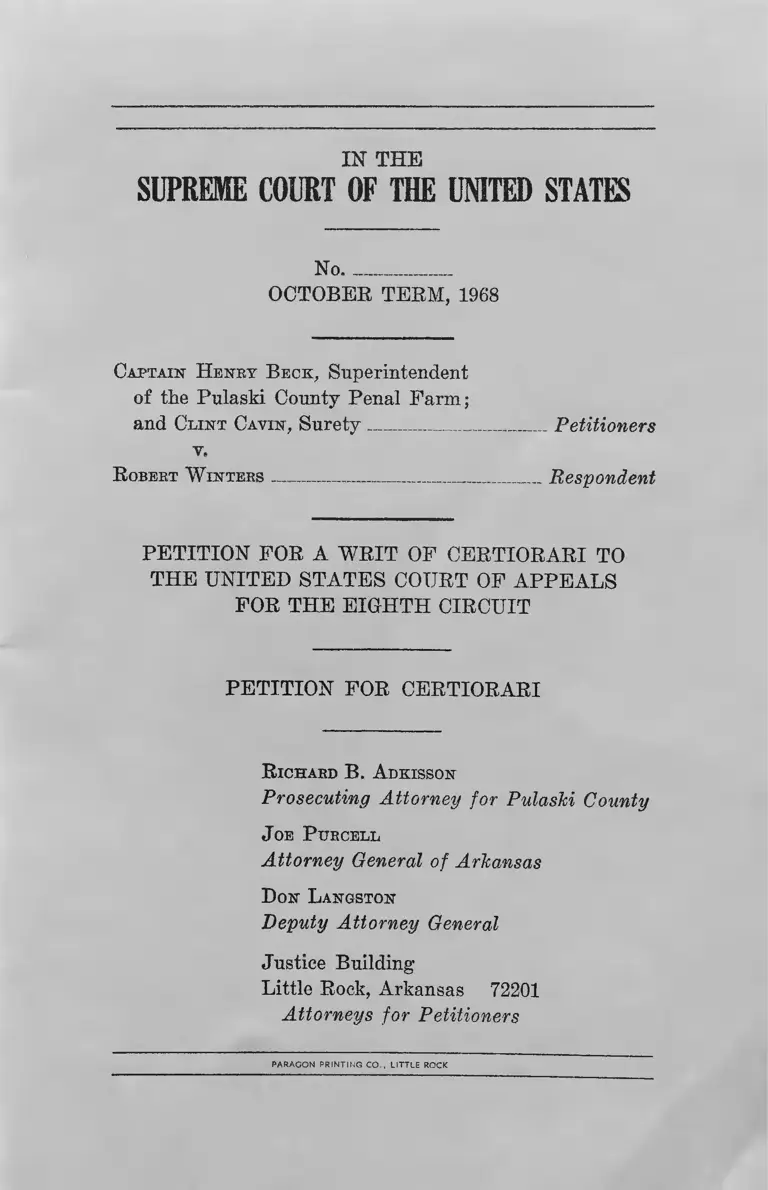

Beck v. Winters Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beck v. Winters Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit, 1969. fafea218-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8f958945-c835-4db2-9921-549adc4be7bd/beck-v-winters-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-eight-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

N o.________

OCTOBER TERM, 1968

Captain H enry Beck, Superintendent

of the Pulaski County Penal Farm;

and Clint Cavin, Surety_______________ Petitioners

v.

R obert W in teb s------------------------------------ Respondent

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

R ichakd B. Adkisson

Prosecuting Attorney for Pulaski County

J oe P ttbcell

Attorney General of Arkansas

Don L angston

Deputy Attorney General

Justice Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Petitioners

P AR AG O N P R IN T IN G C O ., L IT T L E RO CK

I N D E X

Page

Opinions Below _____________________________________ 2

Jurisdiction ______________________________________________ 2

Question Presented ____________________ ___________________ 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes _____________________ 3

Statement ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 5

Argument ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 7

Appendix A _____________________________________________ 13

Appendix B _____________________________________________ 31

Appendix C __________________________ „__________________ 42

Appendix D ----------------- 43

Appendix E —--------------------------------- 44

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

Fourteenth Amendment §1 _!______ ,__________ ____________ 2-3

Sixth Amendment § 1 _____ ___________ _______ .__________ 2-3

ARKANSAS CONSTITUTION

Arkansas Constitution, Art. 2, § 10 ___ _________ _____________ 3

STATUTES

18 U.S.C.A. § 1(3) _________________________________________ 10

23 U.S.C.A. § 2341 ________________________________________ 7

28 U.S.C.A. § 1254 ________________________________________ 2

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 41-1401__________________________________ 10

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 43-1203 _________________ ___________ 2, 4, 7, 9

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 46-502 __________________________________ 3.5

INDEX (Continued)

Page

ORDINANCE

Little Rock City Ordinance § 25-121 ________________________ 5

CASE CITATIONS

Cableton v. State, 243 Ark. 351, 420 S.W. 2d 534_______2, 7, 8, 9, 11

City of New Orleans v. Cook, 249 La. 820, 191 So. 2d 634_______ 11

City of Toledo v. Frazier, 10 Ohio App. 2d 51, 226 N.E. 2d 777...-11-12

Fish v. State, 159 So. 2d 866 (Fla.) __________________________ 11

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) __________._____7, 8,10

Harvey v. Mississippi, 340 F. 2d 263 ________________________ 8

Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U.S. 236 (1963) ---------------------------- 6

McDonald v. Moore, 353 F. 2d 106 ----------------------- ---------------- 8

State v. Sherron, 368 N.C. 694, 151 S.E. 2d 599______________ 11, 12

Watkins v. Morris, 179 So. 2d 348 (Fla.) _____________..._____ ___ 11

Winters v. Beck, 239 Ark. 1151, 397 S.W. 2d 364__________ 2, 5, 7, 9

Winters v. Beck, 385 U.S. 907 __________________________ 5,7,8

Winters v. Beck, 281 F. Supp. 793 --------------------------------------- 2

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No_________

OCTOBER TERM, 1968

Captain H enry Beck, Superintendent

of the Pulaski County Penal Farm;

and Clint Cavin, Surety___ _— ...— Petitioners

v.

R obert W inters .. __Respondent

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

Petitioners petition this court for a Writ of Cer

tiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the 8th

Circuit to review a judgment entered in this case on

February 25, 1969, wherein the Circuit Court of Appeals

for the 8th Circuit affirmed an order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

Western Division, granting petitioners’ petition for a

Writ of Habeas Corpus.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion and order of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, Western

Division, is reported in 281 F. Supp. 793. The opinion

and judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the 8th Circuit are not yet reported. A copy of the dis

trict court opinion is set forth in Appendix “ A” and a

copy of the opinion of the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals for the 8th Circuit is set forth in Appendix “ B ”

to this Petition for Certiorari.

JUBISDICTION

The judgment sought to be reviewed in this case was

entered on February 25, 1969. Jurisdiction of the United

States Supreme Court to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit in this

case is by petition for Writ of Certiorari pursuant to 28

U.S.C.A. §1254.

QUESTION PRESENTED

The 8th Circuit Court of Appeals erred in holding

that the petitioner was denied constitutional rights to

counsel. In other words, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals

has held that the 6th and 14th Amendments to the United

States Constitution requiring Arkansas to appoint counsel

in this misdemeanor case and in effect has held Ark. Stat.

Ann. §43-1203 and the Arkansas practice thereunder pur

suant to the cases of Winters v. Beck, 239 Ark. 1151, 397

S.W. 2d 364 and Cableton v. State, 243 Ark. 351, 420 S.W.

2d 534 unconstitutional.

3

CONSTITUTIONAL PBOVISIONS AND STATUTE

The United States Constitutional Provisions involved

herein are amendments 6 and 14 §1, of the United States

Constitution. Amendment 6 can be found in U.S.C.A.,

C o n s t it u t io n , Amendment 6 to 14, page 4. Amendment

14 §1 can be found in U.S.C.A., C o n st it u t io n , Amendment

14 to end at page 4.

Amendment 6 provides as follows:

“ In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall

enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an

impartial jury of the State and district wherein the

crime shall have been committed, which district

shall have been previously ascertained by law, and

to be informed of the nature and cause of the ac

cusation ; to be confronted with the witnesses

against Mm; to have compulsory process for obtain

ing Witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assist

ance of Counsel for his defense.”

Amendment 14 §1 provides as follows:

“ All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are

citizens of the United States and of the State where

in they reside. No State shall make or enforce

any law which shall abridge the privileges or im

munities of citizens of the United States; nor shall

any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal pro

tection of the laws.”

The Arkansas Constitutional Provision involved

herein is Article 2 §10 and can be found in Ark. Stat. Ann.,

C o n st it u t io n , Yol. 1 p. 33. It provides as follows:

“ In all criminal prosecution the accused shall

enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by im-

4

partial jury of the county in which the crime shall

have been committed; provided that the venue may

be changed to any other county of the judicial dis

trict in which the indictment is found upon the ap

plication of the accused, in such manner as now

is, or may be, prescribed by law; and to be in

formed of the nature and cause of the accusation

against him, and to have a copy thereof; and to be

confronted with the witnesses against him; to have

compulsory process for obtaining witness in his

favor, and to be heard by himself and his counsel.”

The statute involved herein is Ark. St at. Ann. §43-1203

and can be found in Vol. 4A, C r im in a l P rocedure, page

81. It provides as follows:

“ If any person about to be arraigned upon

an indictment for a felony, be without counsel to

conduct his defense, and shall be unable to employ

any, it shall be the duty of the court to assign him

counsel, at his request, not exceeding two [2], who

shall have free access to the prisoner at all reason

able hours.”

0

STATEMENT

On May 13, 1965, Robert Winters, was tried and con

victed in the Little Rock Municipal Court of immorality,

a misdemeanor defined by city ordinance. It is Number

25-121 and is set out in Appendix “ C” . He was sentenced/

to 30 days in jail and fined $254.00, which included costs.

Winters was delivered to the Superintendent of the Pulaski

County Penal Farm to serve his sentence as provided in

Ark. Stat. Ann. §46-502, et seq. Winters was not repre

sented by counsel in the Municipal Court. He did not

ask for the assistance of counsel, nor did the trial judge

inform him of any right to counsel. Although he would

have been! entitled to trial de novo in the Pulaski County

Circuit Ciurt, no appeal was perfected. While serving

his sentence, he obtained counsel and filed a Petition for

a Writ of Habeas Corpus before the Pulaski County Cir

cuit Court, where it was denied. The Circuit Court rul

ing y as sustained on appeal by the Arkansas Supreme

Court. The opinion of the Supreme Court appears in

239 Ark. 1151, 397 S.W. 2d 364. Certiorari was sought

to the United States Supreme Court, and denied. 385

U.S. 907 (Mr. Justice Stewart dissenting).

While the appeal was pending to the Arkansas Su

preme Court Winters was admitted to bail and still re

mains at freedom at $100.00 bond.

Following the denial of Certiorari by the United

States Supreme Court which exhausted State remedies,

Winters filed a Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

on November 8, 1966, in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas, alleging, among

other points, that he had been tried and convicted with

out benefit of counsel and, therefore, in violation of his

6

Constitutional Bights. Initially the District Court dis

missed the petition because the petitioner being at liberty

on bond was not “ in custody” as is required by 23

U.S.C.A. §2341. However, a certificate of probable cause

was obtained in the United States Court of Appeals for

the 8th Circuit, which court on appeal remanded the cause

to the District Court for rehearing on the merits in con

formity with the teachings of the Supreme Court in Jones

v. Cunningham, 371 U.S. 236 (1963) on “ rehearing” the

District Court ruled that the petitioner was not “ in

custody” and, therefore, the District Court had no author

ity, but that the court acting in conformance with the

remand order of the court of appeals would decide the

merits of the case. In deciding the case on its merits

the court considered three points and ruled for petitioner

on one — the denial of counsel. In short, Judge Young

held a hearing and in his opinion found that “ the inter

action of the ‘ dollar-a-day ’ statute of Arkansas with a

$254.00 fine plus a thirty day jail sentence constituted a

‘serious offense’, and the failure of the trial court to

notify petitioner of his right to the assistance of counsel

and offer him counsel if he was unable financially to

retain counsel, rendered the judgment of conviction and

sentence constitutionally invalid.”

We filed a notice of appeal in the District Court which

court issued a certificate of probable cause and an appeal

was taken to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals. The

Circuit Court affirmed the opinion and order of the Dis

trict Court granting Winters’ Petition for Habeas Corpus

ancl petitioners herein have requested and were granted

a stay of the mandate in this case until May 13, 1969.

The purpose of the stay of mandate being to allow us

time to petition the United States Supreme Court for a

Writ of Certiorari to the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals for the 8th Circuit,

7

ARGUMENT

The reasons why we feel that certiorari should be

granted in this case are because the 8th Circuit Court

of Appeals has decided an important state question in

a way in conflict with state law, has decided an important

question of federal law which has not been, but should

be, settled by this court and has decided a federal ques

tion in a way in conflict with applicable decisions of this

court.

ArJc. Stat. Ann. §43-1203 provides for the appoint

ment of counsel for indigents in felony cases. The Ar

kansas Supreme Court in Winters v. Beck, 239 Ark. 1151,

397 S.W. 2d 364, and Cableton v. State, 243 Ark. 351, 420

S.W. 2d 534, has held that this statute only applies in

felony cases and has refused to constitutionally require

appointment of counsel in misdemeanor cases. The de

cision of the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals has held that

an indigent misdemeanor defendant is constitutionally

entitled to the appointment of counsel and therefore is

in conflict with applicable state law.

In Winters v. Beck, 385 U.S. 907, the United States

Supreme Court refused to grant certiorari on the same

question presented herein. The United States Supreme

Court, therefore, has not yet decided that an indigent

misdemeanor defendant is constitutionally entitled to ap

pointment of counsel. The 8th Circuit Court of Appeals

has held that an indigent misdemeanor defendant is con

stitutionally entitled to counsel and this is an important

question of federal law which has not been, but should

be, settled by this court.

This court in Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335

(1963), held that an indigent felony defendant was con-

8

stitutionally entitled to the appointment of counsel but

expressly refused to extend that right to indigent mis

demeanor defendants. The 8th Circuit Court of Appeals

has held that an indigent misdemeanor defendant is con

stitutionally entitled to the appointment of counsel.

Therefore, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals has decided

a federal question in a way in conflict with an applicable

decision of this court, namely, Gideon v. Wainwright,

supra.

We think the Supreme Court of the United States

should grant this Petition for Certiorari in this cause

and we can think of no better reason than that given by

Mr. Justice Stewart in his dissent in Winters v. Beck, 385

U.S. 907 as follows:

“ This decision of the Supreme Court of Ar

kansas is in conflict with decisions of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which

has held that indigent defendants have a constitu

tional right to counsel in misdemeanor cases.

McDonald v. Moore, 353 F. 2d 106; Harvey v. Mis

sissippi, 340 F. 2d 263. This conflict must be re

solved, unless the Constitution of the United States

is going to mean one thing in Arkansas and some

thing else in Mississippi.”

In other words, if Arkansas has to appoint counsel

for misdemeants all the other states should also be subject

to this requirement.

With these preliminary statements in mind as to

why we think this Court should grant this petition for

Writ of Certiorari we proceed briefly into our argument

on the merits concerning the rights to counsel.

It is undisputed that Winters was neither afforded

counsel or advised of any right to have counsel by the

9

Municipal Court. The reason being that Winters was

not entitled to be furnished free counsel by the ruling of

any court which is in the line of authority from the Mu

nicipal Court to the United States Supreme Court. When

the issue was presented to the Arkansas Supreme Court

it ruled against Winters. Winters v. Beck, 239 Ark.

1151, 397 S.W. 2d 364 (1966). When the issue was pre

sented to the United States Supreme Court, certiorari

was denied, 385 U.S. 907.

Traditionally (over 100 years) the State of Arkansas

has provided free counsel for indigent defendants in

felony cases, Ark. Stat. Ann. §43-1203, therefore, the Ar

kansas Supreme Court when once again faced with the

issue of appointed counsel in misdemeanor cases explained

in Cableton v. State, 243 Ark. 351, 358, 420 S.W. 2d 534

(1967) :

“ The practical impossibility of implementing

a system such as appellant urges is obvious when

we consider that there are more justices of the

peace in Arkansas than there are resident practic

ing lawyers and that there are counties in which

there are no practicing lawyers. The impact of

such a rule would seriously impair the administra

tion of justice in Arkansas and impose an intoler

able burden upon the legal profession.”

The Arkansas Supreme Court did not believe that

the rule should be changed except by the Arkansas Legis

lature or the United States Supreme Court. It said:

“ We choose not to anticipate that the Supreme

Court of the United States will extend the rule of

the Wainwright case to misdemeanor cases. We

rather choose to hold that the public policy of this

state on the right to appoint counsel is expressed in

our statutory law. While the statute requiring

appointment of counsel in felony cases was adopted

10

long before the decision in Gideon v. Wainwright,

supra, we take judicial notice that the General

Assembly of our state has met in regular session

twice subsequently. We cannot assume that, in

failing to extend our law to require appointment

of counsel in cases other than felonies, they were

ignorant of that decision. Any change in the law

of Arkansas, after certiorari was denied in the

Winters case, should either come through legisla

tive enactment or by an express decision of the

United States Supreme Court.”

The District and Circuit Courts state that there are

some cases in which there is no requirement for appoint

ing counsel, and other cases where appointed counsel is

a necessity, and the primary concern of the Courts was in

determining where to draw the line. The Courts chose

the rule which prevails in the Federal Courts as provided

in 18 USCA §1 (3), i.e., counsel need not be provided in

petty offenses which are defined as those where the pen

alty does not exceed imprisonment of six months or a fine

of no more than $500.00 or both. Although the city

ordinance in question establishes a maximum punishment

of thirty days imprisonment and a fine of $250.00, the

District and Circuit Courts ruled that the charge consti

tuted more than a petty offense because the fine, if not

paid, must be worked out at $1.00 per day. By the

Courts’ reasoning, there are few, if any, Arkansas statutes

which provide for “ petty offense.” For example, dis

turbing the peace carries a maximum punishment of

$300.00 and six months in jail. Ark. Stat. Ann. §41-1401.

The decision on where to draw the line is one which

requires the balancing of interest and, therefore, is one

which traditionally in the American system of govern

ment belongs to the Legislatures, not to the courts. The

Arkansas Legislature, recognizing its duty to provide

11

counsel for indigent persons enacted such legislation al

most one hundred years ago. Certainly the Federal

Courts should exercise supervision of the States to insure

that individual citizens are not denied fundamental con

stitutional rights. However, the Federal courts should

not undertake to decide in each particular case whether

or not free counsel should have been afforded an accused.

The decisions have recognized the impossibility of furnish

ing counsel to each and every person accused of a crime.

Therefore, the Courts should allow a reasonable latitude

to the Legislatures in solving this problem.

In advancing this argument we, nor our Court, do

not stand alone in taking the position that indigent mis

demeanor defendants are not constitutionally entitled to

counsel. This is pointed out by our Supreme Court in

the Cableton decision, supra:

“ Our decision in the Winters case does not

stand alone. It has been followed or cited with

approval in other jurisdictions. See, e.g., City

of Toledo v. Frasier, 10 Ohio App. 2d 51, 226 N.E.

2d 777; State v. Sherron, 268 N.C. 694, 151 S.E. 2d

599; City of New Orleans v. Cook, 249 La. 820 191

So. 2d 634.

“ In Florida, the arena in which at least five

of the ‘constitutional right to counsel’ cases have

been originally contested, the Supreme Court has

also held that the Wamwright case did not apply to

misdemeanors. They based their holding that an

indigent defendant accused of a misdemeanor was

not entitled to appointed counsel on the action of

their legislature providing for a public defender

for indigents in non-capital felony cases. This

they said, constituted a declaration of the state’s

public policy. Fisk v. State, 159 So. 2d 866 (Fla.) •

Watkins v. Morris, 179 So. 2d 348 (Fla). The

12

Ohio court has also found a declaration of public

policy in its statutes. City of Toledo v. Frasier,

supra. It is suggested by the Supreme Court of

North Carolina that the United States Supreme

Court has not put a responsibility upon a state in

this field any greater than that imposed by its

own statutes. State v. Sherron, 268 N.C. 694,

151 S. E. 2d 599.”

We submit that upon the review of the judgment of

the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals that the judgment be re

versed and the cause remanded to the District Court with

directions to dismiss Winters’ petition for Writ of habeas

corpus because he was not constitutionally entitled to

counsel in this case.

Respectfully submitted,

R ichabd B. Adkisson

Prosecuting Attorney for Pulaski County

J oe P urcell

Attorney General of Arkansas

D on L angston

Deputy Attorney General

Justice Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorneys for Petitioners

13

APPENDIX A

Filed March 5, 1968, Louise A. Rohan, Acting Clerk

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

WESTERN DIVISION

R obert W in t e r s .. Plaintiff

v. No. LR-66-C-227

Ca pt a in H en r y B e c k ,

Superintendent of the

Pulaski County Penal Farm ; and

Cl in t Ga v in , Surety -------- -------_____......_____ Defendants

MEMORANDUM OPINION

On May 13, 1965 the petitioner, Robert Winters, was

convicted in the Little Rock Municipal Court of immoral

ity, a misdemeanor under the provisions of a City Ordi

nance. His punishment was fixed at 30 days in jail and

a fine of $254.00, including costs. Being an indigent and

unable to pay the fine, he was sentenced to the Pulaski

County Penal Farm for a total of 284 days as provided

in Ark. Stats. Ann 19 §2416 (1956 Repl. Vol.).’

At his trial petitioner was not represented by counsel.

He did not ask for the assistance of counsel, nor was he

informed by the trial judge of any right to counsel.

NOTE 1: “19-2416. Persons in jail for violation of city or town

ordinance may be required to work on streets and improve

ment— Prisoners confined in the county jail or citv Drisnn hv

sentence of the Mayor or Police Court, for a violation of a * o?

town by-law, or ordinance, or regulation, may, by ordinance*^ be

required to work out the amount of all tines penalties fnrfoH,, b

and costs, at the rate of one dollar ($1.00) p e /d a y on t ie I reels

Mar Under the C°ntro1 °f the Ci^ Council.^ (Acl

14

Petitioner did not exercise Ms right by appeal to a

trial de novo in the Pulaski County Circuit Court for the

reason, it is alleged in the pending petition, that “ not

having the advice of counsel, petitioner was not aware of

further remedies provided by the Law of Arkansas.”

After his time for appeal had expired, and having

served a portion of his sentence, he secured counsel, who

filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, which was

denied in both the Little Pock Municipal Court and the

Pulaski Circuit Court. He appealed to the Supreme

Court of Arkansas, alleging that Ms constitutional rights

were violated because no lawyer had been appointed to

defend him on the misdemeanor charge in the Municipal

Court. The Supreme Court denied his petition, saying

that Winters had not indicated that he wanted an attorney,

and: “ We have held that no duty is imposed upon the

trial court to appoint counsel for a defendant charged

with a misdemeanor.” 239 Ark. 1151, 397 S.W. 2d 364.

The Supreme Court of the United States denied

certiorari, 385 U.S. 907, Justices Black and Stewart dis

senting.

Prior to its decision, the Arkansas Supreme Court

had admitted petitioner to bail upon a nominal bond of

$100.00. He still remains on that bond.

After relief was denied by the United States Supreme

Court, Winters filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus

in this Court, alleging that his sentence was unconstitu

tional and void for these reasons:

1. Petitioner was tried and convicted without ben

efit of counsel and without being advised of

his right to counsel;

15

2. The penalties assessed against him by the

Municipal Court of Little Rock deprived him

of the equal protection of the laws in that the

substitution of 254 days in jail as punishment

for his failure to pay his fine and court costs

of $254.00 as provided by the Arkansas Statute

arbitrarily imposes imprisonment for no other

reason than indigency;

3. The ordinance pursuant to which he was con

victed violates the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment in that it is vague,

ambiguous, and uncertain.

On February 14, 1967 the Court dismissed the petition

on the ground that the petitioner, being at liberty on bond,

was not under such restraint as was necessary to permit

him to file a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Row

land v. State of Arkansas, 179 F. 2d 709 (8 Cir. 1950).

On March 31,1967 the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit remanded the cause to this Court

“ for a rehearing on the merits in conformity with the

teaching of the Supreme Court of the United States in

Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U.S. 236. ”

Frankly, it had not occurred to this Court that Jones

v. Cunningham was applicable.

In that case is was said:

“ A United States District Court has jurisdic

tion under 28 U.S.C. §2241 to grant a writ of habeas

corpus ‘to a prisoner . . . in custody in violation of

the Constitution . . . of the United States.’ ” 371

U.S. 236.

The question there was whether a state prisoner who had

been placed on parole was “ in custody” within the mean-

16

ing of that section. There, as stated in the opinion, p.

242, petitioner was:

“ confined by the parole order to a particular com

munity, house, and job at the sufferance of his

parole officer. He cannot drive a car without

permission. He must periodically report to his

parole officer, permit the officer to visit his home

and job at any time, and follow the officer’s ad

vice. He is admonished to keep good company

and good hours, work regularly, keep away from

undesirable places, and live a clean, honest, and

temperate life.”

The opinion went on to say, p. 243:

“ While petitioner’s parole releases him from im

mediate physical imprisonment, it imposes condi

tions which significantly confine and restrain his

freedom; this is enough to keep him in the ‘custody’

of the members of the Virginia Parole Board within

the meaning of the habeas corpus statute; ’ ’

Petitioner is under no comparable restrictions under

his bail here. There is no limitation upon his travel, his

employment, his associates, or anything else. He may do

as he pleases. He is only required to render himself

amenable to the order and process of the court. This

is no more restraint than if without bond or bail a sum

mons had been issued directing him to appear before the

court and be amenable to its orders.

If the Mandate of the Court of Appeals means that

we should consider whether or not the petitioner is in

custody as taught in Jones v. Cunningham, we would hold

that he is not and that the petitions should be dismissed

as being prematurely brought. However, the Mandate

is subject to the construction that the Court of Appeals

has found that petitioner is now in such “ custody” and

17

that this Court should hear the petition on its merits.

We proceed to do so.

T h e attack ok t h e o rdinance .

Ordinance No. 25-121 of the City of Little Rock reads

as follows:

“ It is hereby declared to be a misdemeanor

for any person to participate in any public place

in any obscene or lascivious conduct, or to engage

in any conduct calculated or inclined to promote

or encourage immorality, or to invite or entice any

person or persons upon any street, alley, road or

public place, park or square in Little Rock, to ac

company, go with or follow him or her to any

place for immoral purposes, and it shall be un

lawful for any person to invite, entice or address

any person from any door, window, porch or

portico of any house or building, to enter any

house or to go with, accompany or follow him or

her to any place whatever for immoral purposes.

“ The term ‘public place’ is defined to mean

any place in which the public as a class is invited,

allowed or permitted to enter, and includes the

public streets, alleys, sidewalks and thoroughfares,

as well as theaters, restaurants, hotels, as well as

other places. The term ‘public place’ is to be

interpreted liberally.

_ “ Any person found guilty of violating the pro

visions of this section shall, upon conviction, be

fined in any sum not less than ten dollars, nor more

than two hundred and fifty dollars or imprisoned

for not less than five days nor more than thirty

days, or both fined and imprisoned.”

According to the evidence at the trial, petitioner and

Ms woman companion were found in a state of undress

on the “ bed” in the women’s rest room for the use of the

18

public in a Little Eock hotel. It would seem that this

is “ obscene or lascivious conduct” in a “ public place”

by any standard. We do not think that the ordinance is

void on its face, nor that its application here violated

constitutional principles.

S h o u l d c o u n sel be a ppo in ted in all m isd em ea n o r

CASES?

Since Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), sev

eral courts have considered the problem, of whether or not

Gideon requires that counsel be appointed for defendants

in misdemeanor cases. Two of these cases are from the

Fifth Circuit — McDonald v. Moore, 353 F. 2d 106 (1965);

and Harvey v. State of Mississippi, 340 F. 2d 263 — and

these cases are cited by Mr. Justice Stewart in his dissent

from the denial of certiorari in this case, Winters v. Beck,

supra.

In Harvey v. State of Mississippi, after very informal

proceedings before a justice of the peace the defendant

entered a plea of guilty, with the understanding that he

would receive a fine. Later the judge gave him a sentence

imposing a fine of $500 and a 90-day jail sentence. The

court carefully avoided deciding whether or not the rule

in Gideon had been extended to misdemeanor charges in

state tribunals, but apparently because of the jail sentence,

and relying on the reasoning in Evans v. Rives, 75 U.S.

App. D.C. 242, 126 F. 2d 633 (1942), sustained petitioner’s

application for a writ of habeas corpus and voided his

conviction.

In McDonald v. Moore, supra, the defendant had

pleaded guilty in Florida to illegal sale of whiskey, which

is a misdemeanor in that state. A sentence of 6-months

19

in jail or a fine of $250 was imposed. She later at

tempted to withdraw her plea of guilty on the ground

that she was without counsel at the time of arraignment,

but this was denied by the court.

In discussing the problem the court said that now,

under Gideon, states must provide counsel for indigent

defendants in criminal cases to the same extent as the

United States under like circumstances must do in Federal

eases.

The court went on to say:

‘ ‘ It seems unlikely that a person in a municipal

court charged with being drunk and disorderly,

would be entitled to the services of an attorney at

the expense of the state or the municipality. Still

less likely is it that a person given a ticket for a

traffic violation would have the right to counsel

at the expense of the state. If the Constitution

requires that counsel be provided in such cases it

would seem that in many urban areas there would

be a requirement for more lawyers than could be

made available.”

The court in McDonald said that in Harvey v. State,

supra, the Fifth Circuit had rejected the “ serious offense”

rule. It said that it also thought that Gideon had re

pudiated the Betts v. Brady ad hos special circumstance

rule of “ an appraisal of the totality of facts in a given

case.” The opinion said that the court was without

authority to authorize the announcement of a petty offense

rule. Without setting forth any criterion the court said

simply that the facts were similar to those in Harvey v.

State and this was sufficient precedent for the court's

order sustaining the application for a writ of habeas

corpus and the vacation of conviction.

20

Two United States District Courts in the Fifth Cir

cuit have held that Harvey and McDonald required them

to enforce the right to counsel in misdemeanor cases in

state courts. Petition of Thomas, 261 F. Supp. 263

(W.D. La. 1966), Rutledge v. City of Miami, 267 F. Supp.

885 (S.D. Fla. 1967).

But in the Tenth Circuit in a case involving right to

counsel before military tribunals, Chief Judge Murrah

said, “ And, it is an open question whether the Sixth

Amendment right to counsel is applicable in misdemeanor

cases.” Kennedy v. Commandant, U. 8. Disciplinary

Barracks, 377 F. 2d 339 (1967) ;

There is an excellent discussion of the question in the

case of Creighton v. State of North Carolina, 257 F. Supp.

806, (E.D. N.C. 1966) This also arose on an application

for a writ of habeas corpus. Petitioner was convicted of

“ attempt to commit a felony,” which is a misdemeanor in

North Carolina, and was sentenced to twelve months in

jail. The ground for his application for habeas is that

Gideon required that counsel be appointed to represent

indigents tried for misdemeanor. He had not been repre

sented by counsel. In discussing the practical problems

involved, the court said, p. 808:

“ However, unfortunate as it may seem to some,

we live in a society where practical considerations

must be taken into account. It seems obvious that

counsel must be appointed to represent an indigent

on trial for his life; it seems equally obvious that

it is untenable to appoint counsel for an indigent

who has parked too near a fireplug. Somewhere

in between these two extremes a line must be drawn

— the question for decision today is where.”

The court called attention to language used by Mr.

Justice Douglas in his dissent in Bute v. People of State

of Illinois, 333 U.S. 640, 682 (1948).

21

“ It might not be nonsense to draw the Betts

v. Brady line somewhere between that case fa

sentence to imprisonment up to twenty years] and

the case of one charged with violation of a parking

ordinance, and to say the accused is entitled to

counsel in the former but not in the latter . . . yet

it is the need for counsel that establishes the real

standard for determining whether the lack of

counsel rendered the trial unfair. . . . That need is

measured by the nature of the charge and the abil

ity of the average man to face it alone unaided by

an expert in the law.”

The court called attention to the fact that Mr. Justice

Reed in Uveges v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 335

U.S. 437 (1948), noted that some members of the Court

were of the opinion that the Sixth Amendment through

the Fourteenth guarantees counsel in all state criminal

proceedings where “ serious” crimes are charged.

The District Court in North Carolina came to the

conclusion that some misdemeanors involve punishment

which results in a substantial deprivation of liberty or

property, and in such cases counsel should be appointed

to those unable to afford adequate representation.

“ On the other hand, it also recognizes that

some offenses must be considered so minor that

due process does not and cannot require that the

guiding hand of counsel be provided to one charged

with such a violation.. . .

“ The court believes it unwise to set up arbi

trary categories of misdemeanors and hold that in

one category an accused is entitled to counsel while

in another he is not, preferring instead to leave the

matter to the discretion of the trial judge. .

“ (t)his court thinks it wiser to follow the lead

of Mr. Justice Douglas when he said that the need

for counsel is measured by the nature of the charge

(which would include the possible penalty) and the

ability of the average man to face it without the

aid of counsel, and use this standard as a partial

guide to aid the trial judge in the exercise of his

discretion. This provides a much more flexible

and, the court believes, a much more satisfactory

solution to the problem. It recognizes that not

every misdemeanor above a traffic violation re

quires the appointment of counsel while admitting

that some cases of traffic violations can be imagined

where appointment of counsel should be consid

ered. ’ ’

The court said that under the facts in this case it

would not upset the exercise of discretion by the North

Carolina trial judge, and the application for habeas was

denied.

Arbo v. Hegstrom, 261 F. Supp. 397 (D.C. Conn. 1966).

This also involved a petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

The defendant had pleaded guilty to a charge of nonsup

port, a “ non-felony” offense in Connecticut, and was

sentenced to a term of one year in jail. Defendant was

never told that the state would appoint counsel for him,

nor was counsel appointed, although it was within the

discretion of the trial judge to do so.

After discussing Gideon the court said, p. 400:

“ Of course, from a pragmatic point of view,

one can not help but struggle to find some rational

line beyond which the absolute right to counsel

becomes merely a privilege to be provided only

as the particular tribunal sees fit. Although the

administration of criminal justice is cloked in ab

stract principles, these principles are jeopardized

if the system could conceivably break under the

sheer weight of the demands which it imposes.

On a federal level, the recent Criminal Justice Act

of 1964, 18 U.S.C. §3006A, in recognition of the

heavy burden which a requirement of counsel in

every criminal case would impose, has made a

practical and fair compromise with an absolute rule

by prescribing appointment of counsel in other than

“ petty offense” cases.2”

Footnote: “2. 18 U.S.C. §1(3) defines a petty offense as

'any misdemeanor, the penalty for which does not exceed

imprisonment for a period of six months or a fine of not

more than $500, or both . . . . ”

The court went on to say that the facts in the case at

bar did not demand an extension of Gideon because in Con

necticut the crime of nonsupport carried the “ possibility

of a substantial prison sentence” and for the petitioner

this possibility became reality. “ It would be a gross

perversion of solid constitutional doctrine to find a rational

distinction between one year in jail (a misdemeanor) and

one year and a day in prison (a felony).”

The court said that if there was any vitality left in

the “ special circumstances” approach in non-felony cases

its application would necessitate the issuance of the writ

sought. “ The single most relevant consideration under

this test is the ability of the accused to fend for himself,

without benefit of assistance from one trained in the

law. ’ ’

The court held that the failure of the state to apprise

petitioner of his right to appointed counsel and to grant

him that right if it was requested amounted to a denial of

due process.

Another excellent discussion appears in the most

recent case we have found, Brinson v. State of Florida,

County of Dade, 273 F. Supp. 840 (S.D. Florida, Sep

tember 20, 1967). It also arises in the Fifth Circuit.

24

Brinson filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus

seeking relief from his confinement in the Dade County

Jail, Miami, Florida, attacking sentences imposed by the

Metropolitan Court of Dade County.

After pleas of not guilty, petitioner was convicted

of seven traffic offenses — three of them for careless

driving, three for leaving the scene of an accident in

volving personal injury, and driving while under the in

fluence of intoxicating liquor. The penal court pro

vided penalties as follows:

1. Careless driving —■ fine not to exceed $300, or

imprisonment not to exceed 60 days, or both.

2. Driving while under the influence of intoxi

cating liquor —• for the first conviction, im

prisonment not less than 48 hours nor more

than 60 days, or by fine not less than $100 nor

more than $500, or both; for the second con

viction within three years of the first, im

prisonment not less than ten days nor more

than six months, plus fine; and for a third con

viction within five years of first conviction, im

prisonment of not less than 30 days nor more

than 12 months.

3. Leaving the scene of an accident involving per

sonal injuries — for first conviction, imprison

ment for not more than 60 days or a fine of not

more than $500, or both. On second or any

subsequent conviction, imprisonment of not

more than one year or by fine of not more than

$1,000, or both.

For each of the careless driving convictions petitioner

was sentenced to pay a fine of $50 or serve 5 days in

jail; for each of the convictions for leaving the scene of

an accident he was sentenced to a jail term of 20 days

25

and a fine of $200, and in default of payment, an additional

term of 20 days; for driving while under the influence of

intoxicating liquor he was sentenced to 10 days in jail, a

fine of $250, or an additional term of 25 days if the fine

were not paid. Thus, he was sentenced to serve a min

imum jail term of 70 days, plus a total of 100 more days

if he failed to pay the fines. He began serving his time

in April, and having failed to pay any of the fine, he

remained there until the Federal district court ordered

his release in September.

The petitioner was not advised of a right to counsel

or that an attorney would be appointed to represent him

if he could not afford one.

The court said:

“ It is my opinion that the right to assistance

of counsel applies to state court prosecutions for

serious offenses, whether they be labeled felonies

or misdemeanors. The concept of due process

embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment requires

counsel for all persons charged with serious

crimes. . . .

“ In the present case, the petitioner’s convic

tion upon the second offense of leaving the scene

of an accident involving personal injuries exposed

him to a maximum sentence of imprisonment for

one year. The third conviction of the same of

fense exposed him to the possibility of confinement

for an additional year. When a defendant is ex

posed to possible imprisonment for one year, he

is charged with a serious offense. Accordingly,

I hold that petitioner was entitled to assistance of

counsel in the Metropolitan Court to defend against

the two charges aforementioned. The fact that

the offense charged was . . . not termed a felony,

is of no consequence. A man who is charged with

26

an offense for which he can spend a year in jail

is entitled to assistance of counsel regardless of

whether the offense be labeled a felony or misde

meanor. ’ ’

The court pointed out that Gideon v. Wainwright

overruled the “ special circumstances” test of Betts v.

Brady, 316 U.S. 455, regarding right to counsel and that

the Supreme Court has not explicitly recognized that the

existence of the right depends on the seriousness of the

penalty in misdemeanor and traffic cases. The concept,

however, was utilized by the Supreme Court in the case of

In re Gault, 387 U.S. I. This case involved a juvenile

delinquency proceeding in which Gault was determined to

be a delinquent and he was committed to a state institu

tion. On a habeas corpus petition he claimed he was

denied right to counsel.

“ The Supreme Court held that due process re

quired that Gault received assistance of counsel

because ‘the issue . . . whether the child [would]

be found to be “ delinquent” and subjected to the

loss of his liberty for years [was] comparable in

seriousness to a felony prosecution.’ [Emphasis

added] 387 U.S. at 36. The ‘serious offense’

rule, in other words, has been expressly used by the

Supreme Court to determine the right to counsel.”

The court pointed out that:

“ In Gault the court cited the recommendations

of the President’s Crime Commission that counsel

in juvenile eases was necessary to orderly justice.

. . . Their recommendation is explicit: ‘as quickly

as possible . . . counsel [should be provided] to

every criminal defendant who faces a significant

penalty if he cannot afford to provide counsel for

himself.’ [Emphasis added] . . . The meaning

of the recommendation clearly is that all persons

charged with a crime, measured by the magnitude

27

of the penalty, should be entitled to counsel. On

the other hand, the Commission recommends that

‘petty charges’ should be excluded from coverage.”

The court stated that the Criminal Justice Act of

1964, 18 U.S.C. 3006A, divides public offenses into three

categories: (1) felonies, (2) misdemeanors, and (3)

petty offenses.

“ The Act provides for the appointment of

counsel in all cases other than petty offenses. A

petty offense is defined as ‘ [ajny misdemeanor,

the penalty for which does not exceed imprison

ment for a period of six months or a fine of not

more than $500, or both. . . . ’ Title 18 U.S.C. §1.

Not only are funds not provided for court-ap

pointed attorneys, but no duty is placed upon the

United States Commissioner or the court to advise

the defendant that he has the right to be represented

by counsel . . .

“ Accordingly, this Court holds that the con

stitutional right to counsel in non-felony cases de

pends upon the maximum possible penalty under

the offense charged, this being the test whether or

not a ‘serious offense’ is involved. In order that

rights of constitutional stature be uniformly ap

plied, I hold that the minimum offense for which

counsel must be provided is one which carries a

possible penalty of more than six months imprison

ment, which is the line of demarcation drawn in

federal^ practice. In this case, Brinson’s second

and third conviction of leaving the scene of an

accident involving personal injuries must be in

validated since the court failed to notify the de

fendant of his right to the assistance of counsel.”

In a footnote to his dissenting opinion in Winters v.

Beck> suPra> Mr- Justice Stewart said, “ In Arkansas, somJ

28

misdemeanors are punishable by up to three years’ im

prisonment.” [Ark. Stats. Ann. §41-805 (1964 Eepl.

Vol.).] (The statute cited in this footnote is the penalty

provided for conviction of a third offense of illegal co

habitation.)

We do not think that the Sixth Amendment requires

the appointment of counsel for indigent defendants in all

misdemeanor cases without regard to the nature of the

offense charged nor the possible punishment. If we were

required to draw a line we would be inclined to follow the

Florida District Court in Brinson and use the standard

of a petty offense as defined in 18 U.S.C. §1(3).

We do not think that on its face the sentence given

petitioner here of 30 days in jail plus a fine of $254

including costs, coupled with the relatively simple nature

of the charge, is such as to constitute a “ serious offense”

as that term is used in the cases’ discussion of Gideon.

Our problem here, however, is complicated by Ar

kansas’ archaic statute adopted in 1875, referred to by

Mr. Justice Stewart as the “ dollar-a-day” statute. For

an indigent, this translates a $254 fine plus 30 days in

jail to a total of 284 days’ (approximately 9% months)

imprisonment. By any standard this would seem to be

a serious deprivation of a defendant’s liberty.

M at AST INDIGENT BE IMPRISONED FOR FAILURE TO PAY A

PINE?

It is argued by petitioner that the substitution of 254

days in jail as punishment for petitioner’s failure to pay

his fine and court costs arbitrarily imposes imprison

ment for no other reason than indigency. Petitioner

cites Nemeth v. Thomas 35 Law Week 2320 (N.Y. Sup.

2 y

Ct., Dec. 5, 1966), where the defendant was guilty of 138

traffic offenses. Unable to pay the fines, he had been

confined in the workhouse for eight months and he still

had approximately 12 months left to serve. The court

held that continuing imprisonment would constitute ‘ ‘ cruel

and inhuman punishment” and be in violation of the Equal

Protection Clause.

Also cited is a dissenting opinion of Judge Edgerton

in Wildeilood v. U. S., 284 F. 2d 592 (D.C. Cir. 1960),

which indicated that when a person cannot pay a fine and

is therefore imprisoned, the constitutional question arises:

Few would care to say there can be equal justice where

the kind of punishment a man gets depends on the amount

of money he has.”

However, the majority held that when a party is con

victed of an offense and sentenced to pay a fine, it is

within the discretion of the court to order his imprison

ment until the fine shall have been paid (citing Ex Parte

Jackson, 96 IT.S. 727, and Hill v. Wampler, 298 TJ.S, 460,

in which the Supreme Court said: "In the discretion

of the Court the judgment may direct also that the de

fendant shall be imprisoned until the fine is paid . . .” ).

We are not willing to say that imprisonment in lieu

of payment of a fine in the case of an indigent is uncon

stitutional per se. We do say here, however, that the

interaction of the dollar-a-day” statute of Arkansas

with a $254 fine plus a 30-day jail sentence constituted a

"serious offense,” and the failure of the trial court to

notify petitioner of his right to the assistance of counsel

and offer him counsel if he was unable financially to

retain counsel, rendered the judgment of conviction and

sentence constitutionally invalid .

30

An order will be entered by the Court granting the

City of Little Rock a reasonable time to retry petitioner.

If he is not retried within such period, the writ of habeas

corpus will be issued upon application of petitioner’s

counsel.

Dated: March 5, 1968.

Gordon E. Young

United States District Judge

31

APPENDIX B

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 19,278

Captain Henry Beck, Superintend

ent of the Pulaski County Penal

Farm; and Clint Cavin, Surety,

Appellants,

v.

Robert Winters,

Appellee.

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

[February 25, 1969.]

Before M a t t h e s , G ibson a n d L ay, Circuit Judges.

M a t t h e s , Circuit Judge.

Captain Henry Beck, Superintendent of the Pulaski

County Penal Farm and Clint Cavin, surety,1 have ap-

1 Appellant Clint Cavin is surety on Winters’ appearance bond,

and apparently was named as a respondent in the habeas corpus

proceeding on the theory that Winters is in the technical custody

of Cavin. He did not file a responsive pleading in the district court,

32

pealed from the order of the United States district court

granting Robert Winters relief in this habeas corpus pro

ceeding. The history of the litigation giving rise to this

appeal is fully and accurately reported in the district

court’s opinion in Winters v. Beck, 281 F. Supp. 793 (E.D.

Ark. 1968). A brief resume of the relevant facts will

suffice for the purpose of this opinion.

Winters, appellee, was tried and convicted without the

assistance of counsel in the Municipal Court of Little

Rock, Arkansas, for obscene and lascivious conduct pro

scribed by Little Rock City Ordinance No. 25-121. He re

ceived the maximum punishment of 30 days in jail and

a fine of $250, to which was added $4 costs. Being an

indigent and unable to pay the fine, he was sentenced to

the Pulaski County Penal Farm for a total of 284 days

as provided by Ark. Stat. Ann. §19-2416 (1968 Repl.

Vol.).2

After appellee had exhausted his state remedies

through habeas corpus proceedings, Winters v. Beck, 397

S.W. 2d 364 (Ark. 1965), cert, denied, 385 U.S. 907 (1966)

(Mr. Justice Stewart dissenting) he filed a petition for

habeas relief in the United States district court on No

vember 8, 1966. Judge Young initially dismissed appel

lee’s petition on the ground that petitioner was at liberty

on bail and not under such restraint as was necessary to

require consideration of the petition. On appeal we

remanded for a rehearing on the merits in conformity with

the teachings of the Supreme Court in Jones v. Cunning

ham, 371 U.S. 236 (1933). On remand, Judge Young

2 The statute under which appellee was committed provides in

effect that prisoners confined in the county jail or city prison, by

sentence of the mayor or police court, for a violation of a city

ordinance may, by ordinance, be required to work out the amount

of all fines, penalties, forfeitures and costs at the rate of $1 per day.

Little Rock Ordinance No. 25-121, and §19-2416, Ark. Stat. Ann., are

reproduced in the district court’s opinion.

33

held a hearing and in a soundly-reasoned opinion found

that “ the interaction of the ‘dollar-a-day’ statute of Ar

kansas with a $254 fine plus a 30-day jail sentence con

stituted a ‘serious offense,’ and the failure of the trial

court to notify petitioner of his right to the assistance of

counsel and offer him counsel if he was unable financially

to retain counsel, rendered the judgment of conviction

and sentence constitutionally invalid.” 281 F. Supp.

at 801-02.

On this appeal, appellants in their brief again ques

tioned appellee’s standing to seek habeas relief, their

position being that since he was at liberty on bond when

he filed his petition in the United States district court,

he was not in custody within the meaning of 28 U.S.C.

§2241, and consequently the writ was not available to

him. Our remand of the district court’s first order,

motivated by Jones v. Cunningham, supra, disposed of

this issue. In oral argument the Assistant Attorney

General of Arkansas with candor conceded there was no

merit to the lack of standing issue and expressly aban

doned this contention.

The clear-cut question we must decide is whether the

district court was correct in holding that appellee was

deprived of his Sixth Amendment right to assistance of

counsel as applied to the states through the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. We subscribe to

Judge Young’s conclusion and affirm.

The Attorney General of Arkansas argues for a re

versal on the premise that the question of whether an

indigent state defendant is entitled to the assistance of

counsel is one “ which traditionally in the American system

of government belongs to the Legislatures, not to the

courts.” We are reminded that Arkansas has recognized

34

its responsibility by enacting legislation providing “ free

counsel” for indigent defendants in felony cases,3 Ark.

Stat. Ann. §43-1203 (1964 Eepl. Vol.); that the Supreme

Court of Arkansas has held not only that appellee Winters

was not entitled to counsel, but has expressly rejected

the concept that an indigent defendant charged with a

misdemeanor should have the assistance of counsel.

Cableton v. State, 243 Ark. 351, 420 S.W. 2d 534 (1967).

The Cableton Court was obviously influenced by practical

considerations, stating in part: “ [Tjhere are more

justices of the peace in Arkansas than there are resident

practicing lawyers and there are counties in which there

are no practicing lawyers. The impact of such a rule

would seriously impair the administration of justice in

Arkansas and impose an intolerable burden upon the legal

profession.” Id. at 538-39.

We are fully cognizant of and appreciate appellants’

concern over the federal government intruding into prob

lems which are primarily relegated to the states for reso

lution. The Supreme Court recognized the importance

of comity between the federal and state courts in Ker v.

California, 374 TJ.S. 23, 31 (1963).

“Mapp sounded no death knell for our federalism;

rather, it echoed the sentiment of Elkins v. United

States, [364 U.S. 206, 221 (1961)] that ‘a healthy

federalism depends upon the avoidance of needless

conflict between state and federal courts’ by itself

urging that £ [f]ederal-state cooperation in the solu

tion of crime under constitutional standards will

3 Apparently, the legal profession in Arkansas recognizes the need

for more effective legislation in this area. The Arkansas Bar Asso

ciation’s Special Committee on the Defense of Criminal Indigents is

preparing proposed legislation that would establish a public de

fender — appointed counsel system in Arkansas not limited to felony

cases. See Sizemore, Defense of Accused Indigents in Arkansas: New

Hope or More of the Same, Arkansas Lawyer, Oct. 1968, at 6.

35

be promoted, if only by recognition of tbeir now

mutual obligation to respect the same fundamental

criteria in their approaches.’ ”

Accord, Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F. 2d 571 (8th Cir. Dec.

9, 1968).

The sum of appellants’ argument is predicated on the

pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Arkansas that

“ [a]ny change in the law of Arkansas, after certiorari

was denied in the Winters case, should either come through

legislative enactment or by an express decision of the

United States Supreme Court.” 420 S.W. 2d at 537~38.4

Apepllants are correct in suggesting that the Supreme

Court of the United States has not expressly extended the

Sixth Amendment right to assistance^of counsel to misde

meanor cases. We are firmly convinced, however, from

the rationale of the decisions of the Supreme Court that

the fundamental right to counsel extends to a situation

where, as here, the accused has been found guilty of an

offense, which has resulted in imprisonment for approx

imately nine and one-half months.

The Supreme Court in Gideon v. Waimvright, 372

U.S. 335 (1963), in holding that the Sixth Amendment

guarantee of the right to assistance of counsel is applica

ble to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, pro

claimed: “ [I]n our adversary system of criminal justice,

any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a

. ^ Appellants have placed undue reliance upon denial of certiorari

in W inters v. Beck, supra. The sole significance of a denial of a

petition for writ of certiorari is discussed at some length in M aryland

v. Baltim ore Radio Show , 338 U.S. 912, 917-18 (1950). “ISluch a

denial carries with it no implication whatever regarding the Court’s

views on the merit of a case which it has declined to review” Id

at 919.

36

lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is

provided for him.” Id. at 344.5

Appellants seem to regard the Gideon opinion as lim

iting the application of the Sixth Amendment to offenses

which are characterized as felonies. We are not per

suaded that circumscribe the

application of its decision to such narrow conKnes.''1 T h e

all misdemeanors. Indeed, consideration or tne opinion

iiT^ontexTleaSs us to conclude lirahAhe-~»gM-j;o counsel

must be recognized regardless of the label of the offense

if, as here, the accused may be or is subjected to depriva

tion of his liberty for a substantial period of time.6

It should be remembered that the Sixth Amendment

makes no differentiation between misdemeanors and fel-

J onies. The right to counsel is not contingent upon the

length of the sentence or the gravity of the punishment.

Rather, it provides that the guarantee extends to ‘‘all

criminal prosecutions.” Furthermore, we note that the

phrase “ all criminal prosecutions” applies not only to

the right to counsel but also to the right to a jury trial.

Logically the phrase should be accorded the same meaning

5 Gideon expressly overruled BeJis v . Brady, 316 U.S. 455 (1942),

in which the Supreme Court refused to hold that the Sixth Amend

ment right to counsel extended to the states through the Fourteenth

Amendment. Betts did recognize, however, that where there existed

special circumstances, the right to counsel became fundamental and

essential so as to require applicability of the Sixth Amendment to

the state through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

6 Although there is no limitation of the right to appoint counsel

in the majority opinion, Mr. Justice Harlan, in a concurring opinion,

comments: “Whether the rule should extend to all criminal cases

need not now be decided.” Id. at 351. That the reach of Gideon

is not altogether clear is evidenced by two dissenting opinions of

Justices in denials of certiorari in W inters v. Beck, 385 U.S. 907

(1966) and DeJoseph v. Connecticut, 385 U.S. 982 (1966). In those

opinions the Justices call for the Court to clarify its holding in

Gideon.

37

as applied to both protections. Thus we believe sig

nificant the Supreme Court’s pronouncements in cases

involving the jury trial guarantee.

In Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 149 (1968),

the Supreme Court held that “ trial by jury in criminal

cases is fundamental to the American scheme of justice,”

and that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees a right of

jury trial in all state criminal cases “ which — were they

tried in a federal court — would come within the Sixth

Amendment’s guarantee.” The Court concluded that

a jury trial is guaranteed in all “ serious offenses” but

does not extend to “ petty crimes.” The Duncan Court,

however, declined to settle the exact location of the line

between petty offenses and serious crimes. It did hold

that on the facts before it, where appellant had been

sentenced to 60 days in jail and fined $300 for commission

of simple battery, a misdemeanor punishable up to two

years, he was entitled to a jury trial.

In Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1968), the Court

reiterated its holding in Duncan and held that the right

to jury trial extends to serious criminal contempts and

that denial of a jury trial to appellant, who was sentenced

to imprisonment for two years, was constitutional error.

Conversely, in Dyke v. Taylor Implement Mfg. Co., 391

U.S. 216 (1968), the Court did not extend the right to

an offense it found petty. Dyke involved contemnors

who were sentenced under a Tennessee criminal contempt

statute that provided for a maximum penalty of 10 days

in jail and a fine of $50. Relying on its earlier decision

in Chaff v. Schnackenberg, 384 U.S. 373 (1966), where it

held that a six-month sentence is short enough to be

“ petty,” the Court reasoned that the petitioners in this

case were charged with a “ petty offense” and had no

federal constitutional right to jury trial.

38

Equally significant, we believe, is the Court’s recent

declaration that the right to assistance of counsel extends

to juvenile proceedings “ which may result in commitment

to an institution in which the juvenile’s freedom is cur

tailed.” In Re Gault, 387 IT.S. 1, 41 (1967)7

The Fifth Circuit also has been faced with the ques

tion of how far the right to counsel extends and has

refused to formulate a rigid rule which would either

extend the protection to all criminal cases or limit it

only to felonies. Rather, in adopting a broad view it

expressly ruled that the safeguard extends to misdemeanor

cases, but also recognized that there are some offenses

where one would not be entitled to the services of an

attorney at the expense of the state.8

In Harvey v. Mississippi, 340 F. 2d 263 (5th Cir.

1965), the defendant, without being advised that he was

entitled to assistance of counsel, pled guilty to, was con

victed of and sentenced to the maximum punishment of

a $500 fine and 90 days in jail for possession of whiskey,

a misdemeanor in Mississippi. Noting that such a plea

had “ grievous consequences,” the court held that under

the facts of the case, defendant was unconstitutionally

7 The Court stated:

“The juvenile needs the assistance of counsel to cope with prob

lems of law, to make skilled inquiry into the facts, to insist

upon regularity of the proceedings, and to ascertain whether

he has a defense and to prepare and submit it.” Id. at 36.

8 In M acDonald v. Moore, infra, the court commented:

“It seems unlikely that a person in a municipal court charged

with being drunk and disorderly, would be entitled to the serv

ices of an attorney at the expense of the state or the munici

pality. Still less likely is it that a person given a ticket for a

traffic violation would have the right to counsel at the expense

of the state,”

39

convicted because of the failure to advise him that he

was entitled to be furnished counsel.9

In MacDonald v. Moore, 353 F. 2d 106 (1965) the Fifth

Circuit reaffirmed its position in Harvey. There ap

pellant was charged (1) with illegal sale of gin, and (2)

with illegal possession of whiskey and gin, both misde

meanors under Florida law. She pled guilty and was

sentenced to 6 months in jail or $250 fine on each charge.

Because the facts in the case were so similar to those

in Harvey, the court stated that it was required to hold

that appellant was entitled to assistance of counsel.

Recently, the Fifth Circuit again dealt with the ques

tion and expressly held that under the Sixth and Four

teenth Amendments, right to counsel extends to misde

meanor cases. Goslin v. Thomas, 400 F. 2d 594 (1968).’°

Defendant asserted that he had been denied counsel in

four Louisiana misdemeanor proceedings. In the last

proceeding, defendant had been sentenced to jail for one

year.

9 The court quoted from Evans v. R ives, 126 F. 2d 633, 638 (D.C.

Cir. 1942) approvingly:

“It is . . . suggested . . . that the constitutional guaranty of the

right to the assistance of counsel in a criminal case does not

apply except in the event of ‘serious offenses’. No such dif

ferentiation is made in the wording of the guaranty itself, and

we are cited to no authority, and know of none, making this

distinction. . . . And so far as the right to the assistance of

counsel is concerned, the Constitution draws no distinction be

tween loss of liberty for a short period and such loss for a long

one.”

*0 The lower court’s opinion, 261 F. Supp. 263 (W.D. La. 1966),

held that under H arvey and M acDonald, Gideon must be applied to

all criminal cases. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit stopped

short of this holding, stating that the only question was whether

the right to counsel under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments

extends to state misdemeanor cases.

40

Based on the rationale of the foregoing authorities,11

we conclude that the right to counsel cannot be dependent

upon the mere arbitrary label that a state legislature at

taches to an offense.12

We find it unnecessary to decide that all indigents

have the right to assistance of counsel in all misdemeanor

prosecutions, no matter how trivial may be the conse

quences. Whether a person accused of an offense labeled

as a misdemeanor is entitled to counsel must be resolved

upon proper consideration of all circumstances relative

to the question. In addition to the financial status of

the accused, the punishment that may be imposed if

he is found guilty is certainly a vital factor. The trial

court should fully explore all of the relevant circum

stances, and if it is determined that counsel should be

provided, the accused must be so informed. Unless he

intelligently and knowingly waives the right, counsel

31 Other federal cases rejecting the misdemeanor-felony dichotomy

and holding that the Sixth Amendment right to assistance of counsel

extends to misdemeanor prosecutions are: Brinson v. Florida, 273

F Supp 840 (S.D. Fla. 1967); R utledge v. City of Miami, 267 F,

Supp. 885 (S.D. Fla. 1967); Arbo v. H egstrom , 261 F. Supp. 393-

(D. Conn. 1966). See Stubblefield v. Beto, 399 F. 2d 424, 425 (5th

Cir. 1968) (dissenting opinion); W ilson v. Blabon, 370 F. 2d 997

(9th Cir. 1967). See also the following articles: Carlson, Appointed,

Counsel in Criminal Prosecutions; A Study of Indigent D efense, 50

Iowa L. Rev. 1073 (1965); Kamisar, B eits v. Brady T w enty Years

Later: The Right to Counsel and Due Process V alues, 61 Mich. L.

Rev. 219 (1962); Kamisar and Choper, The R ight to Counsel in M in

nesota: Som e F ield F indings and L egal-P olicy O bservations, 48

Minn. L. Rev. 1 (1963); Milroy, Court A ppointed Counsel for Indigent

M isdem eanants, 6 Ariz. L. Rev. 280 (1965); Comment, The R ight to

Counsel for M isdem eanants in State Courts, 20 Ark L. Rev. 156

1966).

12 As Mr. Justice Stewart pointed out in his dissent in the Court’s

denial of certiorari in W inters v. Beck, supra, some misdemeanors

in Arkansas are punishable by up to three years’ imprisonment. Ark.

Stat. Ann. §41-805 (1964 Repl. Vol.).

41

should be furnished. We go no further in attempting

to delineate the guidelines.13

In summary, it is abundantly clear that the district

court correctly decided the question at issue. The order

vacating the judgment and sentence is affirmed.

A true copy.

Attest:

Clerk, U.S. Court of Appeals, Eight Circuit.

13 While we do not formulate and lay down an arbitrary, me

chanical rule which could automatically and simply be applied in

every case to determine whether the right to assistance of counsel

attaches, we do point out some of the various approaches and sug-

gesions promulgated by courts, commissions and statutes. In Brinson

v. Florida, 273 F. Supp. 840 (S.D. Fla. 1967), the court constructed

what it believed to be the proper test: “The right to assistance of

counsel is determined by the seriousness of the offense, measured

by the gravity of the npnanvrtn which me defendant is exposed on

any given violation” Id. at 843. The court further stated: “I hold

that the minimum offense for which counsel must be provided is

one which carries a possible penalty of more than six months im

prisonment, which is the line of demarcation drawn in federal

practice.” Id. at 845. The Criminal Justice Act of 1964, 18 U.S.C.

§3006(a), provides that appointed counsel in federal courts shall be

afforded to indigents in all felony and misdemeanor cases other than

petty offenses. The Act defines petty offenses as those punishable

by not more than six months imprisonment or $500 fine or both.

18 U.S.C. §1. The ABA’s project on Minimum Standards for Criminal

Justice in its tentative draft on Standards R elating to Providing

D efense Services §4.1 (1967) has recommended the following rule:

“Counsel should be provided in all criminal proceedings for

offenses punishable by loss of liberty, except those types of

offenses for which such punishment is not likely to be imposed,

regardless of their denomination as felonies, misdemeanors or

otherwise.

In the C hallenge of Crime in a Free Society. A Report by the P resi

dent's C om m ission on Law Enforcem ent and A dm inistration of

Justice (1967), the commission recommended:

“The objective to be met as quickly as possible is to provide

counsel to every criminal defendant who faces a significant

penalty, if he cannot afford to provide counsel himself. This

should apply to cases classified as misdemeanors as well as to

those classified as felonies.” Id. at 150.

In its summary, however, the commission stated that “traffic and

similar petty charges” are excluded from this recommendation. Id.

at viii.

42

APPENDIX C

L it t l e R ock C ity O r d in a n ce N o. 25-121 — It is

hereby declared to be a misdemeanor for any person to

participate in any public place in any obscene or lascivious

conduct, or to engage in any conduct calculated or in

clined to promote or encourage immorality, or to invite

or entice any person or persons upon any street, alley,