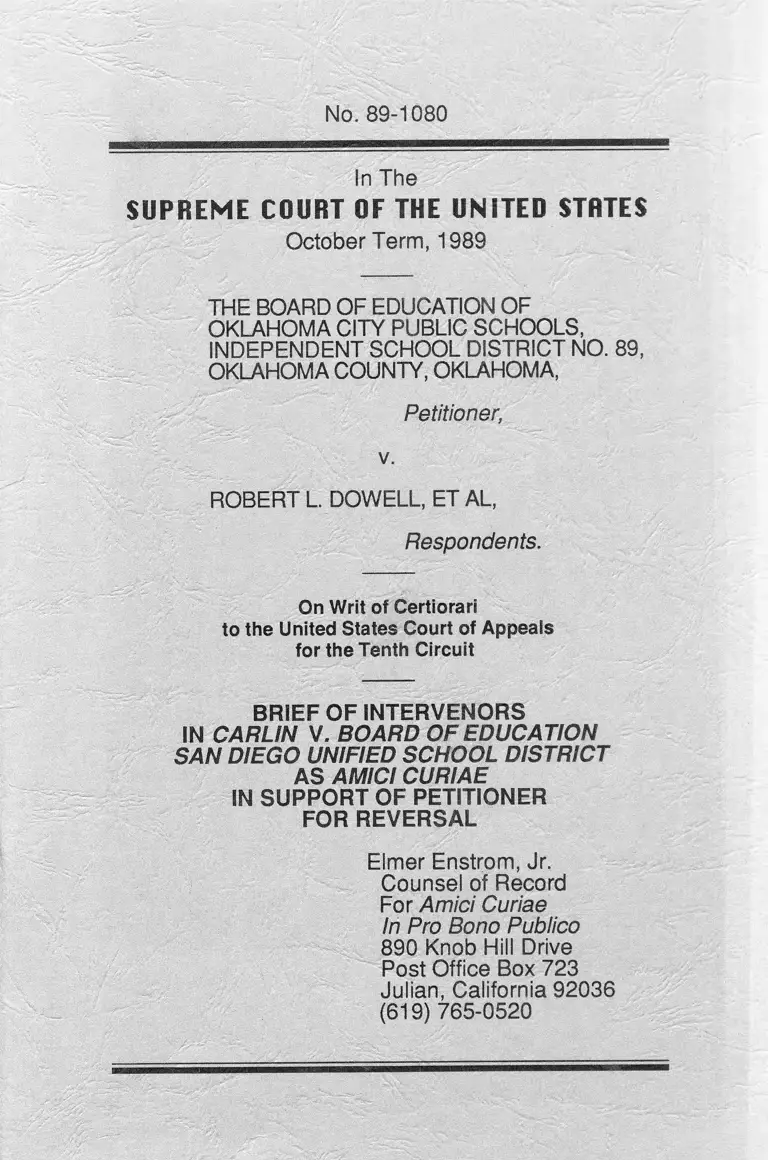

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief of Intervenors Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner for Reversal

Public Court Documents

May 8, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief of Intervenors Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner for Reversal, 1990. 0d586c3f-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8fcbc158-f2d9-43d1-81c0-04b5605c1e33/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-of-intervenors-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner-for-reversal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 89-1080

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1989

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS,

INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 89,

OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

Petitioner,

v.

ROBERT L. DOWELL, ET AL,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF OF INTERVENORS

IN CARLIN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION

SAN DIEGO UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT

AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

FOR REVERSAL

Elmer Enstrom, Jr.

Counsel of Record

For Amici Curiae

In Pro Bono Publico

890 Knob Hill Drive

Post Office Box 723

Julian, California 92036

(619) 765-0520

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AU TH O RITIES............................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI C U R IA E ...................................... 1

SUMMARY OF A R G U M E N T .......................................... 3

ARGUMENT

l. BACKGROUND: DESEGREGATION CASES

ARE U N IQ U E................................................... .... 5

A. Amici Curiae's Presentation is Appro

priate ........................................................ 5

B. History Leading to Swann Doctrine , . 7

C. The Swann Doctrine Does Not Favor

Protracted B using ..................................... 9

II. COURT-EXTENDED RACIAL ASSIGNMENTS

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DISCRIMINATE

AGAINST UNWILLING K-4 BYSTANDERS 11

m . COURT-EXTENDED DISCRIMINATORY

ASSIGMENTS UNCONSTITUTIONALLY

IMPAIR THE LIBERTY AND PRIVACY OF

UNWILLING K-4 BYSTANDERS . . . . 17

CONCLUSION ................................................................. 19

APPENDIX ........................................................................... 1A

Page

Amer. Meat Institute v. Environ. Protect. Agcy.,

526 F.2d 442 (7th Cir. 1975) . . . . . . . . 6

Austin Independent School District v. United

States, 429 U.S. 990 ( 1 9 7 6 ) ............................ 3,11

Bank of California v. Superior Court, 16 Cal.2d

516(1940) .................................................................. 18

Board of Ed., Etc. v. Superior Court o f Cal.,

448 U.S. 1343 (1980)............................................... 12

Bob Jones University v. United States,

456 U.S. 922 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ............................................... 2

Bob Jones University v. United States,

461 U.S. 574 ( 1 9 8 3 ) ............................ 2,4,5,16-17

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) . 13-14,19

Brown v. Board of Education, 341 U.S. 483

(1954) (Brown I ) .......................................... passim

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) (Brown I I ) ................................................4,13-17

Carlin v. Board of Education, San Diego

Superior Court No. 303,800 1-3,12,19

Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal.3d 280

( 1 9 7 6 ) ...................................................................... 6

Crawford v. Board of Education, 113 Cal.App.3d

633 (1980) 15

Crawford v. Board o f Education, 458 U.S. 527

( 1 9 8 2 ) ................................................................. 6,12

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Ill

Dowell v. Okl. City Public Schools, Ind. Dist 89,

677 F.Supp. 1503(W.D.Okl. 1987) . . . . passim

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) . 4,18

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

( 1 9 6 8 ) .......................................................... 8-10

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District,

5 9 C a l.2 d 8 7 6 (1 9 6 3 )......................................... 6-7

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo.,

413 U.S. 189 ( 1 9 7 2 ) ............................ 3,4,8,17

Martin v. Wilks, 109 S.Ct. 2180,2185 (1989) . 4,18

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) . . . . 18

Monroe v. Board of Com rs o f City o f Jackson,

Tenn., 391 U.S. 452 (1968) 12

Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510

( 1 9 2 5 ) .......................................................... 4,18

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) . . . . 7

Regents o f University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ............................................... 16

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

( 1 9 7 1 ) ....................... passim

Constitutional Provisions:

California Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 7A . . . . . 6

United States Constitution,

Amendment V, Due Process Clause . . 4,19

Amendment XIV, Equal Protection Clause . 7

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

IV

Other Authorities: Page

Coleman, A Scholar Who Inspired It Says Busing

Backfired, (Interview, The National Observer,

June 27, 1975) 13

Coleman, The Concept of Equality o f Educa

tional Opportunity, reprint in The "Inequality"

Controversy, Levine and Bane, Editors (Basic

Books,1 9 7 5 ) ............................................................. 13

Cox, The Role o f the Supreme Court in

American Government (Oxford Press, 1976) . . 15

Note, 51 Cal.L.Rev. 810 ( 1 9 6 3 ) .............................. 6

Schwartz, The Supreme Court, (Ronald Press,

1957) ............................................................. - • 7

Warren, Memoirs of Earl Warren (Doubleday,

1977) 17

Wright, Witkin on Appellate Court Attorneys,

54 Cal.S.Bar J. 106 (1 9 7 9 ) ..................................... 9

BRIEF OF INTERVENORS

IN CARLIN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION

AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

FOR REVERSAL

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE*

Amici Curiae are Intervenors—opposing mandatory

racial assignments—in the school desegregation case entitled

Carlin, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Board o f Education, San Diego

Unified School District, Defendant; Groundswell, et al.,

Intervenors, No. 303800, Superior Court, San Diego County,

California. This Court may take judicial notice of proceedings in

the "Carlin" case.

The Carlin complaint, based upon stare decisis appli

cation of judicial decisions, was filed December 4, 1967, as a

class action by certain black students, among others, versus the

Defendant Board of Education to "integrate" the San Diego

Unified School District. The class was described in the Order

Determining Existence of Class Action, filed December 7, 1973,

as—

"All students attending the San Diego Unified School

District and their parents and legal guardians who believe

that said schools should be racially balanced, if necessary

through court order."

A m ici—including an association of persons called

"Groundswell," and some individual students and their parents—

intervened on December 15, 1980. They alleged in their

complaint in intervention (pp. 8-10) that it was unconstitutional

to assign the six intervening students and other students

similarly situated, because of their race, to particular schools.

Amici later offered proof of signed petitions by 1856

District students, each "object(ing) to school authorities making

*This brief is filed with the consent of the parties; letters consenting to the

filing of this brief have been lodged with the Clerk.

2

me, because of my race, go away from my neighborhood public

school location to classes, without my consent and the consent

of my parents, as a violation of my rights." Although these

petitions were not received in evidence, their existence was

established and an excerpt from an exemplar, marked as a part of

Carlin Interveners' Exhibit 6 for Identification, is annexed as

the Appendix. See Carlin reporter's transcript of proceedings,

July 16, 1981, pp. 190- 197.

Although the Carlin Court has filed an "Order re

Integration Plan/Final Order" on May 21, 1985, which like the

trial court's order herein permits neighborhood school

assignments, it has retained continuing jurisdiction (p.12).

Thus, those having the status of Amici students remain subject

to renewal of the contention that racial imbalance through causes

not attributable to them call for their being racially reassigned

beyond their neighborhood schools.

Here, as the dissent to the majority opinion at 890 F.2d

1483 on October 6, 1989, states, "this (Tenth Circuit) court re

tains jurisdiction and now orders the (Oklahoma City) school

district to racially balance the elementary schools which will

most certainly require busing." 890 F.2d at 1506. Should the

panel majority's order be allowed to stand on this record, San

Diego "anti-busing" students would become even more

vulnerable to a request for racial balancing under the stare

decisis doctrine.

The unwillingness of a number of students to be racially

assigned away from their neighborhood schools may be inferred

from the trial court's finding of the probability of "white flight"

if a "busing" order is carried out. Dowell v. Okl. City Public

Schools, Ind. Dist. 89, 677 F.Supp. 1503 at 1525 (1987).

Such "busing" assignments would be a form of racial

discrimination, another form of which prompted the appointment

of an amicus curiae in Bob Jones University v. United States,

456 U.S. 922 (1982). It raises issues sufficiently similar to

those in Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574

(1983), to garner additional support therefrom for considering

the following presentation by Amici Curiae.

3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

All Oklahoma City students in grades K-4 have been

allowed to attend their neighborhood schools since 1985 when

the compulsory racial assignments to other schools, required by

a 1972 desegregation plan, were ended by the school board.

The District Court upheld the neighborhood school plan in June,

1987 (after a hearing in which it dissolved the 1972

desegregation decree), finding that during the plan's operation

the school system has been "unitary" under the Sw ann

Doctrine. Dowell v. Okl, City Public Schools, Ind. Dist. 89,

677 F.Supp. 1503,1519,1526 (1987). SeeSwann v, Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1,32 (1971).

A divided three-judge panel of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, over a vigorous dissent by Judge

Bobby R. Baldock, reversed the district court decision and dis

approved the neighborhood school plan. 890 F.2d 1483. The

panel majority's decree will require the racial assignments of

unwilling students to reduce the racial imbalance that the panel

found to exist in some of the K-4 schools. See dissent, 890

F.2d at 1506.

The appellate desegregation decree is unique, to echo

Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr,, because its burden-compelling

children to leave their neighborhood and spend significant time

each day being transported to a distant school—will fall upon

innocent children and parents who are not charged with any

offending action. Austin Independent School District v.

United States, 429 U.S. 990, at 995, Footnote 5 (1976), and

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo. (1972), 413

U.S. 189 at 247, Powell, J., concurring.

Amici complained in their intervention (pp. 9-10) that the

imposition of such a burden upon the intervening students in

Carlin, and other San Diego students similarly situated, would

racially discriminate against them and unconstitutionally infringe

upon their liberty and privacy. These grounds apply with added

force here in that the permanent nature of the proposed burden

upon five-to-ten-year-olds disregards the Swann remedy

limitations referred to by the trial court. Dowell, supra, 677

4

F.Supp. at 1521. Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 23,31-32.

When a mandatory elementary school assignment, under

these conditions, is based solely upon the race of an unwilling

child, that child is unconstitutionally discriminated against,

regardless of the purpose, under the racially neutral language in

Brown v. Board o f Education (Brown II), (1955) 349 U.S.

294, at 298 "that racial discrimination in public education is

unconstitutional."

Court-ordered racial assignments away from one's

neighborhood school impair the assigned children's liberty and

privacy, to paraphrase Justice Powell in Keyes, supra, 413

U.S. at 247. They violate the Fifth Amendment of the

Constitution as to those unwilling, innocent assignees of tender

age unable to obtain continuing individual representation, who

are not parties, regardless of its purpose. For those children

have not had the hearing that Amendment requires by its clause

that "(n)o person shall...be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law." Compare Martin v. Wilks, 109

S.Ct. 2180,2185 (1989).

This Court may consider these children's rights favorably.

Compare Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925);

Griswold v. State o f Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 481 (1965);

and Bob Jones University, supra, 461 U.S., at 593.

In summary, these Oklahoma City students are

constitutionally protected from being racially discriminated

against and having their liberty and privacy impaired by being

mandatorily reassigned indefinitely to other than their

neighborhood elementary schools for racial balance.

5

ARGUMENT

I. BACKGROUND: DESEGREGATION CASES

ARE UNIQUE

A divided United States Court of Appeals three-judge

panel for the Tenth Circuit has held unconstitutional the discon

tinuance of busing for racial balance and the adoption of a

neighborhood school plan for K-4 students by petitioner because

it has left some schools racially imbalanced. 890 F.2d 1483.

The trial court had dissolved the injunction under a 1972

desegregation decree requiring such busing, holding that the

school system had retained a unitary status and that the

neighborhood plan had been adopted without discriminatory

intent. Dowell, supra, 677 F.Supp. at 1515-21.

Judge Baldock, in dissent, deplored the panel majority's

failure to terminate jurisdiction "when a system has achieved and

maintained unitary status." 890 F.2d at 1506. Fn. 1. The

dissent emphasized Justice Powell's observation commencing

his dissents in the 1979 Columbus and Dayton desegregation

cases, that "25 years after Brown v. Board, o f Edue. (Brown

I)... 'the federal judiciary should be limiting rather than

expanding the extent to which courts are operating the public

school systems of our country.'" 890 F.2d at 1506. Fn. 1.

To meet the terms of the appellate order, Amici believe the

trial court will have to order the petitioning school board to

indefinitely reassign nonconsenting, nonparty elementary

students, solely on a racial basis, beyond their neighborhood

schools along the lines sought by Respondents at the trial. See

Dowell, supra, 677 F.Supp. at 1524-25.

A. Amici Curiae's Presentation is Appropriate

The affirmative relief rendered by the panel majority

adversely affects parties not joined in Oklahoma City, and

others like the students in San Diego and elsewhere by virtue of

the stare decisis doctrine. And it is inconsistent with the

national policy against racial discrimination in education, as set

forth in Bob Jones University, supra, 461 U.S. at 593. These

6

exceptional circumstances permit Amici to present issues

beyond that of the impact of "white flight" upon the litigants.

Compare Amer. Meat Institute v. Environ. Prot. Agcy., 526

F.2d 442, at 449 (7th Cir. 1975).

Contentions by amici curiae, raised in behalf of nonparty

students, have been considered in desegregation cases. A key

pronouncement in the seminal California case of Jackson v.

Pasadena City School Dist., 59 Cal.2d 876, at 881, rendered

June 27, 1963, pertained to school district responsibility for

affirmative integration in schools in addition to the defendant

Pasadena district:

"The right to an equal opportunity for education and

the harmful consequences of segregation require that

school boards take steps, insofar as reasonably feasible,

to alleviate racial imbalance in schools regardless of its

cause."

Footnote 5 in Note, 51 Cal.L.Rev. 810 (1963) points out

that the complaint in Jackson, supra, —

"was drawn on the theory of affirmative segregation and

in the intermediate appellate court, counsel for plaintiff

expressly denied that he was advocating affirmative

integration. 210 A.C.A. at 658, 16 Cal.Rptr. at 665.

The question was not argued in the briefs of either party.

Affirmative integration was urged, however, in two

amici curiae briefs."

This dictum, under the stare decisis doctrine, became the

basis of the decision in 1976 in Crawford v. Board of

Education, 17 Cal.3d 280, which decreed affirmative integra

tion (which continues in effect except as to "busing") in

California without the showing of de jure segregation required

by federal decisions. The "busing" authorized by Crawford

was disallowed by a 1979 "anti-busing" amendment to Section

7A, Article I, of the California Constitution, ultimately upheld

in Crawford v. Los Angeles Board of Education, 458 U.S.

527, at 533 (1982).

7

Like the amici in Jackson, supra, Amici here are

presenting underlying issues involving nonparties, which may

be entertained favorably.

B. History Leading to the Swann Doctrine

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court held in Plessy

v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, that the segregation of the races in

transportation facilities did not violate the Constitution so long as

the facilities were equal. The majority opinion rationalized that

any discrimination felt by black persons assigned to separate

facilities, since they were equal to those used by whites, was

"not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because

the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." 163

U.S. at 551.

Justice John Marshall Harlan (I) vigorously dissented, and

his rationale is summarized by Professor Bernard Schwartz in

The Supreme Court (Ronald Press, 1957) at page 269:

"Yet, even if the Plessy Court were correct in its

assumption that segregation is not discrimination, that

would not make its doctrine consistent with the equal

protection clause. For that clause bars the states from

making legal distinctions that are not supported by

reasonable legislative classifications, and, as already

emphasized, classification on the basis of race must be

deemed irrational. Our Constitution, to use the apt

description of the dissenting Justice in the Plessy case, is

color-blind; it neither knows nor tolerates classification

on racial grounds."

Plessy was overruled in 1954 when Brown v. Board

of Education (Brown I) , 347 U.S. 483, 495, declared that "in

the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal'

has no place," and that by forcing the black plaintiffs to attend

separate schools solely because of their race, the respondents

denied them equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution. In Brown /, the Court was

considering the complaints of black children that they were

discriminated against by being segregated solely because of

8

their race in separate public schools administered by the

respondent school authorities under the laws of Kansas, South

Carolina, Virginia and Delaware, respectively.

Brown I agreed with Justice Harlan I as to the uncon

stitutionality of such actions under state laws permitting or

mandating them. However, it did not mention the Harlan

dissent and tended to focus upon their effect (segregation)

rather than the acts of discrimination. Brown I was initially

construed as negative in nature, calling only for state neutrality,

as explained by Justice Powell in his concurrence in Keyes,

supra, 413 U.S. 189 at 220:

"It was impermissible under the Constitution for the

States, or their instrumentalities to force children to attend

segregated schools. The forbidden action was de jure,

and the opinion in Brown I was construed—for some

years and by many courts—as requiring only state

neutrality, allowing 'freedom of choice' as to schools to

be attended so long as the State itself assured that the

choice was genuinely free of official restraint."

Justice Powell goes on to say in Keyes that the doctrine

of Brown I, as amplified by Brown II, did not retain its

original meaning:

"In a series of decisions extending from 1954 to

1971 the concept of state neutrality was transformed into

the present constitutional doctrine requiring affirmative

state action to desegregate school systems. The keystone

case was Green v. Country School Board, 391 U.S.

430, 437-438... (1968), where school boards were

declared to have 'the affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in

which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch.'" 413 U.S. 220.

Thus, Justice Powell explained, the affirmative-duty

concept articulated in a rural setting in Green flowered in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, supra,

into a new constitutional principle of general application to large

9

urban areas as well.

C. The Sw ann D o c trin e D oes Not F a v o r

P ro tracted Busing

A truism in the American system of justice is that it is

delegated to the counsel of the parties the task of shaping the

issues which are brought before the appellate courts. Edward

M. W right, Witkin on Appellate Court Attorneys, 54

Cal.St.Bar Journal 106 (1979).

The issues were shaped in Brown, Green and Swann--

relied on for judicially-ordered busing of bystanders—by the

counsel for the only parties to those actions, namely, the

minority plaintiffs versus the defendant school authorities.

In Swann, a desegregation plan had been approved for a

large urban district by the District Court in 1965 based on

geographic zoning with a free transfer provision, leaving some

schools racially imbalanced. 402 U.S. at 6,7 (1971).

After the decision in Green and companion cases, the

Swann plaintiffs moved in September, 1968, for further relief

based on those cases. The District Court then in effect required

a plan desegregating all the schools, including the elementary

schools, to be accomplished by busing students beyond their

neighborhood schools so that the student bodies throughout the

system would range from 9% to 38% black. Id. at 7-11.

This Court noted that all the parties agreed (emphasis

by Amici) that "in 1969 the system fell short of achieving the

unitary system that those (Green and companion) cases

require;" but that the board..."reiterated its view that the plan

was unreasonable." Id. at 7,11.

Dealing with the facts and issue thus presented to it, this

Court stated:

"O n the facts of this case, we are unable to

conclude that the order of the District Court is not

reasonable, feasible and workable..." Emphasis

10

supplied. Id. at 32.

However, the Court also indicated the temporary nature of

the judicial role.

"At some point, these school authorities and others

like them should have achieved full compliance with this

Court's decision in Brown I. The systems will then be

'unitary' in the sense required by our decision in Green

and Alexander.

"It does not follow that the communities served by

such systems will remain demographically stable, for in a

growing, mobile society, few will do so. Neither school

authorities nor district courts are constitutionally required

to make year-by-year adjustments of the racial

composition of student bodies once the affirmative duty

to desegregate has been accomplished and racial

discrimination through official action is eliminated from

the system. This does not mean that federal courts are

without power to deal with future problems; but in the

absence of a showing that either the school authorities or

some other agency of the State has deliberately attempted

to fix or alter demographic patterns to affect the racial

composition of the schools, further intervention by a

district court should not be necessary." Id. at 31,32.

When this Court was considering the reasonableness of

the Swann plan the whites were a majority of 71% in the

Charlotte school system. 402 U.S. at 6. In Oklahoma City, the

whites are becoming a minority (from 73% in 1969 to 47% in

1986); and the rest-blacks (40% in 1986) and others classified

as "minorities" (13% in 1986)-are a emerging majority, (from

27% in 1969 to 53% in 1986), which will accelerate with

expanded busing. Dowell, supra, 677 F.Supp. at 1509, 1525.

The absence of "anti-busing" students as parties in Swann

claiming a constitutional right not to be racially bused from their

neighborhood schools led to a lack of reference to that right in

considering the board's claim the busing plan was unreasonable.

11

"An objection to transportation of students may

have validity when the time or distance of travel is so

great as to risk either the health of the children or

significantly impinge on the educational process... It

hardly needs stating that the limits on time of travel will

vary with many factors, but probably with none more

than the age of the students. The reconciliation of

competing values in a desegregation case is, of course, a

difficult task with many sensitive facets but fundamentally

no more so than remedial measures courts of equity have

traditionally employed." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at

31,32.

Consideration of the bystanders' rights under the different

circumstances in this case is warranted in the light of the

Swann Court's statement that "(a)bsent a constitutional

violation there would be no basis for judicially ordering

assignment of students on a racial basis. All things being equal,

with no history of discrimination, it might well be desirable to

assign pupils to schools nearest their homes." Id. at 28.

II . CO U RT-EX TEN D ED RA CIAL ASSIGNM ENTS

U N CO N STITU TIO N A LLY D ISC R IM IN A TE A-

GAINST UNW ILLING K-4 BYSTANDERS

"(A) desegregation decree is unique in that its

burden falls not upon the officials or private interests

responsible for the offending action but, rather upon

innocent children and parents."

So Justice Powell concluded in Footnote 7 in concurring

in Austin Independent School District, supra, 429 U.S. at 995.

The authority for burdening innocent children under the

desegregation decree below rests upon precedents interpreting

Brown v. Board o f Education. As shown, these precedents

were established in cases in which "anti-busing" students were

not parties and their rights were not individually articulated.

That there are many such objecting students of various races is

evidenced by their actions when the reversal of a Los Angeles

Superior Court's busing order became effective on April 20,

12

1981. Among about 7,000 students immediately returning to

their neighborhood schools for the few remaining weeks of the

school year were 4,300 "minority" students. Crawford, supra,

458 U.S. at 534, Fn. 10. Here, the dissent noted support of the

neighborhood plan by two black parents, one of whom had

collected 400 signatures favoring it. 890 F.2d at 1531. Fn. 25.

The unique position of these children is pointed out in

terms of their parents' feelings by the Carlin Court in its

Memorandum Decision and Order on March 9, 1977:

"There is a substantial percentage of minority

parents, as well as majority parents, who prefer to have

their children attend neighborhood schools (footnote

omitted). Most 'Hispanics’ (41% of the minority school

population) do not want their children sent to 'Anglo’

schools where they will not have the security, fellowship

and bilingual program of the neighborhood school. A

substantial number of black parents also object to

’busing' for various reasons. These parents have not

had an opportunity to be heard in these proceedings..."

Page 21.

And school board attempts to present nonparty views by

arguing, for instance, "flight by whites," if bused, have been

considered irrelevant because "the vitality of these constitutional

principles (justifying busing) cannot be allowed to yield simply

because of disagreement with them." Monroe v. Board of

Com'rs of City of Jackson, Tenn., 391 U.S. 452,459 (1968).

Consequently, "anti-busing" students have been treated as

"elements" in school desegregation cases in the manner

described by then-justice William H. Rehnquist in his order

denying the request of the school board for a stay of a "busing"

order in Board of Ed., Etc. v. Superior Court o f Cal. (1980)

448 U.S. 1343 at 1348:

"...The Board's primary contention here is that

'white flight,' which all parties concede has taken place in

the school district, will accelerate if this plan is put into

effect... Because projections indicated that the school

13

district in 1987 will consist of only 14% white students,

the Superior Court asserted that its task was to achieve

the optimal use of white students in the schools so that

the maximum numbers of schools may be desegregated.

"I find this analysis somewhat troublesome, since it

puts ’white' students much in the position of textbooks,

visual aids, and the like-an element that every good

school should have. And it appears clear that this Court,

sooner or later, will have to confront the issue of 'white

flight' by whatever term it is denominated..."

Since the decision of the Court of Appeals below raises the

specter of "white flight," it is appropriate to confront that issue

in the broad sense both of the meaning of that term and of the

holding in Brown v. Board of Education.

Dr. James A. Coleman, senior author of the 1966

Equality o f Educational Opportunity Survey, points out that the

flight from city schools beyond the reach of mandatory busing

orders, which accelerates when blacks begin outnumbering

whites, has included "middle-class" blacks as well as whites.

A Scholar Who Inspired It Says Busing Backfired. T he

National Observer, June 27, 1975, pp. 1,18.

Dr. Coleman describes the actual decision in Brown as

"in fact a confusion of two unrelated premises: this new

concept, which looked at results of schooling, and the legal

premise that the use of race as a basis for school assignment

violates fundamental freedoms." The Concept o f Equality of

Educational Opportunity, reprinted in Part III of!The

"Inequality" Controversy, Donald N. Levine, Mary Jo Bane,

Editors (Basic Books, 1975), Page 206. This is a fair

description when Brown I and Brown II are read together

with Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

The "new concept" is derived from the initial answer to the

question in Brown I whether "segregation of children in public

schools solely on the basis of race even though the physical

facilities may be equal deprive(s) the children of the minority

group of equal educational opportunities?" 347 U.S. at 493.

14

The Court's immediate answer was that such segregation, with

the sanction of law, had a detrimental effect upon their

educational opportunities, as denoting their inferiority, having

the tendency to retard their educational and mental development,

and depriving them of some of the benefits they would receive in

a racially integrated school system. This is social in nature

because it rests primarily upon evidence then available from the

social sciences cited in Brown I, 347 U.S. at 494, Fn. 11.

But Brown rests also on the legal premise stated in

racially-neutral language in Brown II that "(t)he opinions (of

Brown I and Bolling)... declaring the fundamental

principle that racial discrim ination in public

education is unconstitutional, are incorporated herein by

reference." 349 U.S. at 297. (Emphasis added.) It is too

narrow a reading of Brown to consider that "racial

discrimination in public education is unconstitutional" only in

terms of detrimental result to a particular minority perceived

primarily, if not entirely, from their ratio to students of other

races in some schools of a school system.

Bolling found that the separation of black plaintiffs from

whites in the District of Columbia, which could be accomplished

only by the use of racial classifications, was so unjustifiable as

to deprive plaintiffs of their liberty in violation of the Due

Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Bolling, supra, 348

U.S. at 498-9. The use of racial classifications, which Bolling

referred to (348 U.S. at 498) and disapproved, was no less a

factor in accomplishing the separation of "minority" students in

Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina and Virginia, as was

recognized in Brown II by the incorporation of Bolling.

Brown II ruled that the district courts were to supervise

the school districts involved in all three decisions in their

"transition to a system of public education freed of racial

discrimination." 349 U.S. at 299. This consistent use of

racially-neutral language in Brown II proscribing racial

discrim ination emphasizes Brown's legal premise. It is

distinguishable from Brown's social premise because its major

influence are principles which bind the judges as well as the

litigants, and which apply uniformly to all persons not only

15

today but yesterday and tomorrow. See, generally, Archibald

Cox, The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government

(Oxford Press, 1976), pp. 109-113.

The two premises are compatible in Brown I because the

unconstitutional racial separation and consequent detriment

suffered by those so separated was caused by a violation of the

legal premise that "racial discrimination in public education is

unconstitutional..." Brown II, 349 U.S. at 297.

However, the social premise is not applicable here because

of changes in the conditions from those in Brown. Among the

changes, in addition to eliminating the type of deliberate racial

separation condemned by Brown, are the many continuing

affirmative remedial steps to integrate the system set forth by the

trial judge. Dowell, 677 F.Supp. at 1522-24 (1987).

Another change is the progressive outnumbering of whites

by "minorities" in Oklahoma City. The stare decisis

applicability of Brown's social premise when whites became

significantly outnumbered was questioned by a California Court

of Appeal in Los Angeles, after noting in Crawford v. Board of

Education, 113 Cal.App.3d 633,642(1980) that the school

district was 53.6% white in 1968:

"That (outnumbering) of course is the existing

situation in the District, where white students are now a

minority in that they comprise 23.7 percent of the total

student population and 16.1 percent of grades K-3. Yet

for the purposes of applying the legal principles related to

school segregation, whites are still designated as the

'majority,' and segregation is viewed in terms of the

minorities, or any one of them, being isolated from

whites." 113 Cal.App.3d 633 at 648 (1980).

"That approach appears to be a hangover from the

historic situation in some areas of the county which

produced the background against which the decision in

Brown v. Board o f Education, supra, was rendered.

"The wisdom of, or the need to, perpetuate that

16

approach here is questionable since, when considered in

terms of the ethnic composition of the Los Angeles

Unified School District, it appears to denigrate the dignity

and capability of the minority students. In effect, it

implies that ethnic 'minority' children, even when they

constitute a numerical majority and thus do not suffer the

psychological trauma of deliberate isolation, cannot

achieve best results except in the presence of a token

number of white students." Id., Footnote 3.

The cause of the objectionable result found in Brown

was racial busing of students like complainant Brown past their

neighborhood schools for the social purpose of racial separation.

But in reliance upon the social premise, more is now sought than

allowing such students to attend their neighborhood schools, or

to attend other schools voluntarily for integrative purposes, and

continuing other integrative programs. What is sought is that the

petitioning school authorities come full circle and reinstate racial

busing of elementary students, some being no more willing than

complainant Brown, past their neighborhood schools for the

social purpose of racial mixing.

Under these facts, the equal protection guarantee to all

persons does not entitle Respondents to a degree of protection

greater than that accorded other students. Regents o f University

of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, at 295 (1978).

The interests advanced by Amici may be compared to

those advocated by the amicus in Bob Jones University, supra,

461 U.S. 574. Bob Jones University, a private religious

university, had a policy prohibiting interracial dating and

marriage by its white and black students. This was racially

discriminatory, according to Internal Revenue Service policy,

which formed the basis for denying a claimed tax exempt status.

Id. at 581.

This Court pointed out that there is a national policy

against racial discrimination in education, and that the

Government has a fundamental, overriding interest in

eradicating it. Id. at 593,604. The Court found that the

university policy was a form of racial discrimination and upheld

the amicus' position in support of the judgment below finding

17

the IRS policy was properly applied to Bob Jones University.

Id. at 605.

Judicially-assigning unwilling bystanders to particular

schools solely on the basis of their race is no less a form of

racial discrimination than was the policy of Bob Jones

University. Elements adding to the persuasiveness of this

argument which were not present in the Bob Jones case, are

that the racial discrimination here is to be imposed under court

duress (1) by public officials (2) in a public school system (3)

upon students of tender age whose attendance is compelled.

Racial assignments of unwilling Oklahoma City K-4

students violate Brown's legal premise, applying to them in

1985, today and tomorrow, as restated by Chief Justice Earl

Warren in The Memoirs of Earl Warren (Doubleday, 1977) at

pages 287-88:

"Again the Court was unanimous in its decision of

May 31, 1955, reaffirming its earlier decision of May 17,

1954, by asserting the fundamental principle that any

kind of racial discrimination in public education is

unconstitutional, and that all provisions of federal, state,

or local law requiring or permitting such discrimination

must yield to this principle." (Emphasis by Amici.)

II I . CO U RT-EX TEN D ED D ISC R IM IN A TO R Y AS

SIG N M EN TS U N C O N STITU TIO N A LLY IM

PA IR TH E LIBERTY AND PRIVACY OF

U N W ILLIN G K-4 BYSTANDERS

"Any child, white or black, who is compelled to

leave his neighborhood and spend significant time each

day being transported to a distant school suffers an

impairment of his liberty and privacy." Justice Powell,

concurring, in Keyes, supra, 413 U.S. at 247.

For some thirteen years black students (in K-4 grades) and

white students (in 5th grade) were assigned to schools for racial

balance in Oklahoma City under the Finger plan until 1985 when

the board allowed K-4 students to return to their neighborhood

18

schools. The appellate decision below would require

resumption of K-4 racial school assignments of students,

including nonconsenting, white bystanders, away from their

neighborhood schools.

The law does not permit the courts to render the type of

affirmative relief which injures and affects the interests of third

parties not joined in the action. Martin, supra, 109 S.Ct. at

2185. Compare Bank o f California v. Superior Court, 16

Cal.2d 516 (1940).

This Court may take judicial notice of the injury suffered

by unwilling, affected students and their inability to individually

intervene and continuously assert their constitutional rights. Nor

are they required to. Martin, supra, 109 S.Ct. at 2185. This

Court may consider their rights under the circumstances.

Compare Griswold, supra, 381 U.S. at 481, and Pierce,

supra, 268 U.S. 510.

Children are not mere creatures of the State. They are

constitutionally protected from governmental action infringing

upon their liberty and privacy. Pierce, supra, 268 U.S. at 535.

Mandatory racial assignments of five-to-ten-year-olds

away from their home/neighborhood school environs are

analogous to the assignments of seven-year-olds in ancient

Sparta referred to in Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

In Meyer , this Court prevented Nebraska from

prohibiting foreign-language instruction in its schools, making

the point that a desirable end cannot be promoted by prohibited

means by this analogy:

"In order to submerge the individual and develop

ideal citizens, Sparta assembled the males at seven into

barracks and intrusted their subsequent education and

training to official guardians. Although such measures

have been deliberately approved by men of great genius

their ideas touching the relation between individual and

state were wholly different from those upon which our

institutions rest; and it hardly will be affirmed that any

19

Legislature could impose such restrctions upon the people

of a state without doing violence to both letter and spirit

of the Constitution." 262 U.S. at 402.

The Fifth Amendment provides that "no person shall be

deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of

law." This Court, in construing that clause, pointed out in

Bolling, supra, 347 U.S.at 498, that discrimination "may be

so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process." And racially

assigning unwilling Oklahoma City students to particular

elementary schools is as unjustifiable under the circumstances

here as were the racial assignments of District of Columbia

students in Bolling.

Unwilling bystanders racially reassigned by the judicial

arm of the United States would suffer an impairment of liberty

like that of the students in Bolling. They are entitled to a ruling

of unconstitutionality such as the Bolling students received after

a hearing. A fortiori, since the deprivation of liberty and

privacy is sought to be imposed upon nonparty Oklahoma City

students without their being heard as required by the Due

Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

C O N C LU SIO N

For these reasons, the Intervenors opposed to judicially

ordered assignment of students on a racial basis in Carlin v.

Board o f Education, San Diego Unified School District, as

amici curiae, respectfully support the Petitioner and the

neighborhood school plan.

Respectfully submitted,

Elmer Enstrom, Jr.

Counsel for Amici Curiae

In Pro Bono Publico

890 Knob Hill Drive

Post Office Box 723

Julian, California 92036

(619) 765-0520

Dated: May 8, 1990

mS 'rZ S £ > £ 7 v n £

1A

APPENDIX

(Child, living in District, subject to busing,

■ who can read and understand the statement below

TO THE BOARD OF EDUCATION, SAN DIEGO UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT:

I, the undersigned child, residing in the San Diego Unified School

District, respectfully object to school authorities making me, because

of my race, go away from my neighborhood public school location to

classes, without my consent and the consent of my parent(s), as a

violation of my rights.

NAME

C.n

ChoXjujL of

. ti

H A r m

~ 0

AGE ADDRESS ________ DATE

W k .

< i x i a / 9 , m i

V

' 1h I t I 3 r \Ss'l

I d x u ^ A .

m ± Z $

l XU Lk .

-Q 2 I 2 M

S M I .

lL_____

Si Ll .

-E fh jS d j^

f?h. P M j

02J2A

7 tU m J r 2 0 ,9\

,_______ P

A e r n i

r f f e i v

- f— - -

(LhlAJjLl

(Excerpt,L.Lester

_ l L l c

- ± L J.a

- i x Z

Declaration Intervenors'

? 7 7 t v

i&SlCz!—

Z U l± L

1j/x /9 j >. -j^dxJ2 3 $

Ex.6 Id.,Carlin,7/16/8}