Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Reply Brief, 1962. ae7b8bea-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8fef5372-3668-42c6-8eb0-8874f2c4c0a3/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

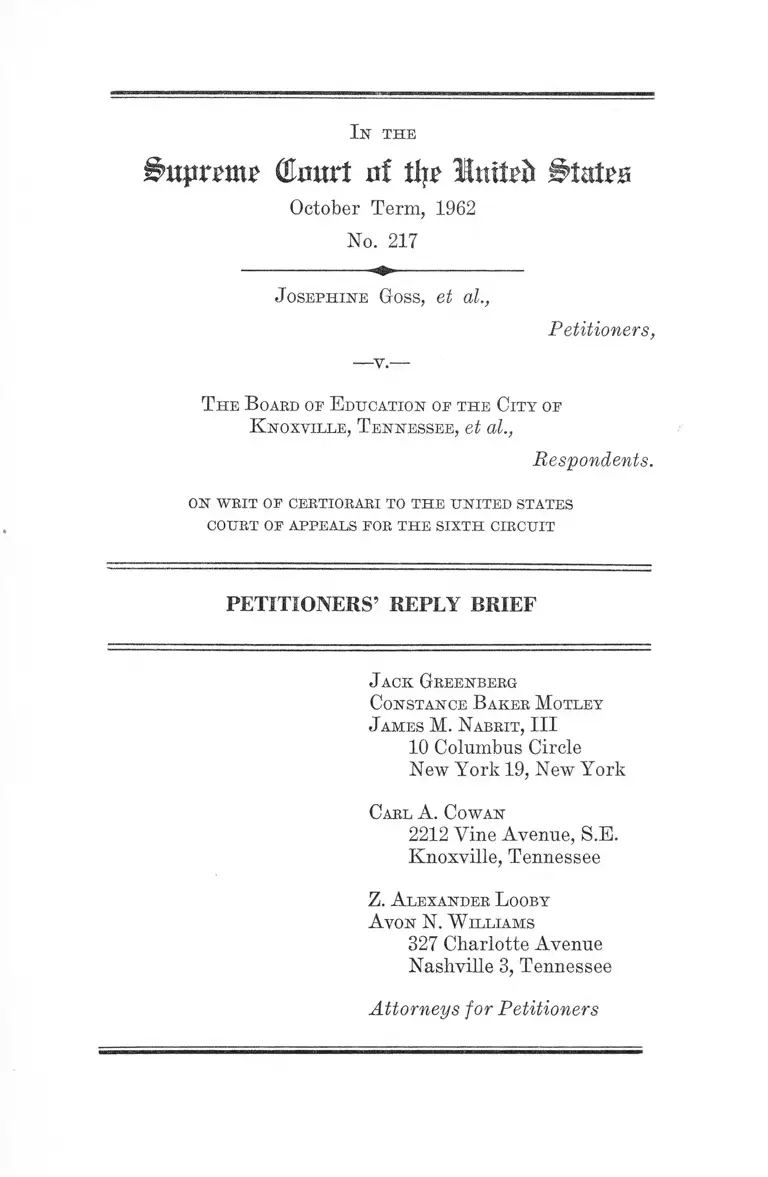

I n the

Court of tljr 1 nitrft States

October Term, 1962

No. 217

J osephine Goss, et al.,

Petitioners,

—-v —

T he B oard op E ducation op the City op

K noxville, T ennessee, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiams

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n the

Olmtrt af tin' luttrii BtnUs

October Term, 1962

No. 217

J osephine Goss, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

T he B oabd of E ducation oe the City op

K noxville, T ennessee, et al.,

Respondents.

on writ op certiorari to the united states

COURT OP APPEALS POR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

PETITIONERS’ REPLY BRIEF

Respondent City of Knoxville urges that the racial trans

fer provisions “are under review here only as transition

measures” (Knoxville Br. 3). Referring to “disorders . . .

occurring in a community only eighteen miles from Knox

ville . . . ” it argues that “In Knoxville only in rare instances

will white parents permit their children to go to predomi

nantly Negro schools, and the majority of Negro parents

won’t let their children go to predominantly white schools”

(Knoxville Br. 4). Knoxville argues also that “there is an

assumption,” which it calls valid, “that requests for trans

fer based upon race are supported by actual good cause

which stems from race” {Id. at 5). But the Board concedes

it could make transfer following individual evaluations

under Paragraph 5 of its plan, which covers “all cases,

including those of handicap due to race” {Id. at 6). While

2

Knoxville concedes such individuation is possible in the

case now before the Court, the city urges that other com

munities may not be able to manage it; therefore, Knox

ville also should be able to use race as a gross factor in

justifying transfers {Id. at 6).

Respondent Davidson County Board of Education prin

cipally makes the argument1 that “the Fourteenth Amend

ment did not guarantee the students an integrated school

to attend; and any segregation was not the result of the

plan but of individual choices of individual students”

(Davidson County Br. 11-12). Amicus curiae Chattanooga

and Memphis School Boards make the same argument

(Chattanooga Br. 3, et seq.; Memphis Br. 5, et seq.).

T h e R acial T ra n sfe r F eatures A re o f In d e fin ite D ura tion .

In reply, petitioners submit first that the racial transfer

provision is not casually incidental to the desegregation

plan, but is as permanent as any other feature of school

administration in the respondent communities. Moreover,

the option is an unconstitutional racial discrimination and

perpetuates the segregated system.

There is no evidence whatsoever in the record that either

racial transfer provision is temporary or designed to oper

ate only during a period of transition—although if this

were true their invalidity would be nonetheless obvious.

Notably, no party or amicus (including the United States

which condemns the transfer provision but views it as

temporary) (United States’ Br. 18) cites anywhere to the

record to demonstrate that the option is temporary. Of

course, all equity decrees under continuing jurisdiction

may be called temporary in the sense that they may be

modified; but modifications must be related to unforeseen

1 This Respondent here relied on the dissent in Dillard v. School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, 308 F. 2d 920 (4th Cir. 1962).

3

changes in conditions, United States v. Swift S Co., 286

U. S. 106. All policies and practices of school hoards are

subject to change. Perhaps the transfer provision was

assumed to be transitional because it was coupled to a

twelve-year desegregation plan. But under this view

coalescence of the Negro and white zones (R. 52, 214)

might also be called temporary. And other features, ob

viously of a permanent nature, also might be termed

transitional, e.g., paragraphs 5 of the Knoxville and 4 of

the Davidson County plans (transfers may be allowed for

“good cause”) (R. 52-53, 214),2 6 of Davidson County plan

(pupil registration to be held in the spring) and 7 of

Davidson (transportation to be furnished to eligible

students) (R. 215). None of these, however, may be as

sumed to terminate at any time in the foreseeable future,

and on their face are permanent. There is no reason to

assume that the racial transfer features are limited in a

way that these are not.

Indeed, the racial feature should be read in the light

of Respondents’ proven desire to accomplish no more

desegregation than compelled to. Knoxville’s Answer as

serts that so far as Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483; 349 U. S. 294, is concerned “The decisions of that

[this] Court are never unchangeable, and a different mem

bership in the future may order differently . . . [although]

there does not now exist reasonable support for the

proposition” that this will occur “within the foreseeable

future” (R. 27). Knoxville has asserted a desire to per

petuate segregation “indefinitely” (R. 79-80) and features

of its plan which retain segregation should be read in that

light. Davidson County similarly made no effort to fulfill

2 The Knoxville supervisor of child personnel testified that the

racial transfer provisions would merely add an additional ground

for transfer to the system theretofore employed for 23 years (R.

117) ; he nowhere suggested that this addition was temporary.

4

its constitutional duty to desegregate until specifically com

pelled by judicial decree.

It is more reasonable to assume on these records that

these respondents would like to retain as much segregation

as they can for as long as they can, and the plans, therefore,

do not permit bare assumptions that their racial features

will disappear at some indeterminate time in the future.

On this record, the inescapable conclusion is that after the

grade-a-year features of the plan have been exhausted, the

transfer provisions will remain on the books unless ex

pressly repealed or invalidated by judicial decree.

T h e Racial O p tio n P lans A re U n co n stitu tiona l S ta te

A ctio n W h e th er T em p o ra ry or N ot.

The racial option is based on an “assumption” (Knox

ville Br. 5) “that requests for transfers based upon race

are supported by actual good cause which stems from

race” {Ibid.). Knoxville refers to “common knowledge”

that embarrassment, harm and handicap flow from desegre

gation. The Davidson County brief (p. 7) refers to a

desire to transfer “to avoid a radical departure from cus

tom ; or the fear of student friction. . . . ” Both of these

plans, in actual application, allow “paper” transfers, that

is, pupils simply choose their schools on the basis of race

before going to any school (R. 141, 219-220). Therefore,

neither plan requires transfers on the basis of the ex

perience of individual children but, a priori, each allows

an option as to whether one desires to be desegregated

or not.

This is, of course, contrary to the principal assertion of

respondents’ briefs, state action in a number of senses.

(1) It is a complex of private and state conduct in the

nature of such a combination condemned in N. A. A. C. P.

v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449. (2) Moreover, by rule of the

5

State, a Negro child is denied the right to transfer in a

situation wherein a white child explicitly has that right

and vice versa. This seems to fly in the face of the most

elementary reading of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483. If children may not be assigned on the basis

of race, why should they be permitted to transfer on this

basis ?

But beyond this, and far more invidious, is (3) the fact

that the plans so structure the school systems as to per

petuate segregation for as long as possible (R. 104, 108,

226, 277). Thus, this Court’s admonition that school dis

tricts are to act as promptly as possible to convert from

systems of segregation to “systems” (Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 IT. S. 483, 494; 349 U. S. 294, 300; Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 115), of nonsegregation is thwarted by

a standard of system-wide application designed to per

petuate segregation to the greatest degree possible while

affording token compliance stretched out over a long period

of time.

Petitioners certainly do not contend that if an individual

child has proven difficulties in a particular educational

situation, the school officials may not do whatever is neces

sary to alleviate his personal difficulties. But petitioners

submit that seldom, if ever, should such a child be per

mitted transfer on a racial basis. Certainly at the very

least all other reasonable avenues of approach to the

problem should be exhausted before, even in an individual

case, school authorities may consider race.

Racial distinctions between citizens “are by their very

nature odious to a free people”, Hirabayashi v. United

States, 320 U. S. 81, 100, and are constitutionally suspect,

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216; cf. Bolling

v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497. One of the principal impediments

6

to effectuating the decision of this Court in Brown v. Board

of Education, supra, has been that resistance has taken the

form not so much of outright defiance as of perpetuation of

segregation under forms nominally unrelated to race.

Indeed, Knoxville argues in substance, and in advance

of investigation of particular cases, that if it were per

mitted to transfer children on an individual basis because

of objections to racial desegregation, the end result would

be essentially what it seeks to accomplish under the racial

option transfer provision (Knoxville Br. 6). This is a par

ticularly dangerous prospect for law enforcement when,

as in Knoxville, “The Board’s serious, frank deliberations

on the subject of desegregation were not in the formal open

meetings” (R. 59).

Therefore, while no rule of law can entirely guard against

decisions which express unstated privately arrived at con

siderations, any rule which encourages or even allows con

siderations of race greatly expands the opportunity to

maintain segregation under other labels. The deliberate

speed formula allowed time for the solution of specified

administrative problems and other problems in like cate

gories. It explicitly excluded hostility to desegregation as

ground for delay, but because of its generality it could not

prevent its being used as it was in Knoxville and Davidson

County as a basis for doing nothing until a court order

were entered against the defendants. To the extent that

the deliberate speed concept, as one resting essentially

on administrative considerations, were to be loosened to

allow for “transitional problems of personal adjustment

. . . even when they originate in customs fixed by race”

(Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae 25; Knoxville

Br. 3) it will offer additional ammunition to those forces

in communities which want to do nothing, even though

there also exist in those- communities forces which desire

7

to comply with the Constitution. To the extent that the

compliance formula is tightened to eliminate any express

racial consideration, it will strengthen the hand of those

who desire to do their constitutional duty.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiams

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

3 8