Whitfield v. Clinton Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whitfield v. Clinton Brief Amicus Curiae, 1991. 6d8d0e11-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8ff8e7ba-e758-40f2-bcb3-33a337e9486d/whitfield-v-clinton-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

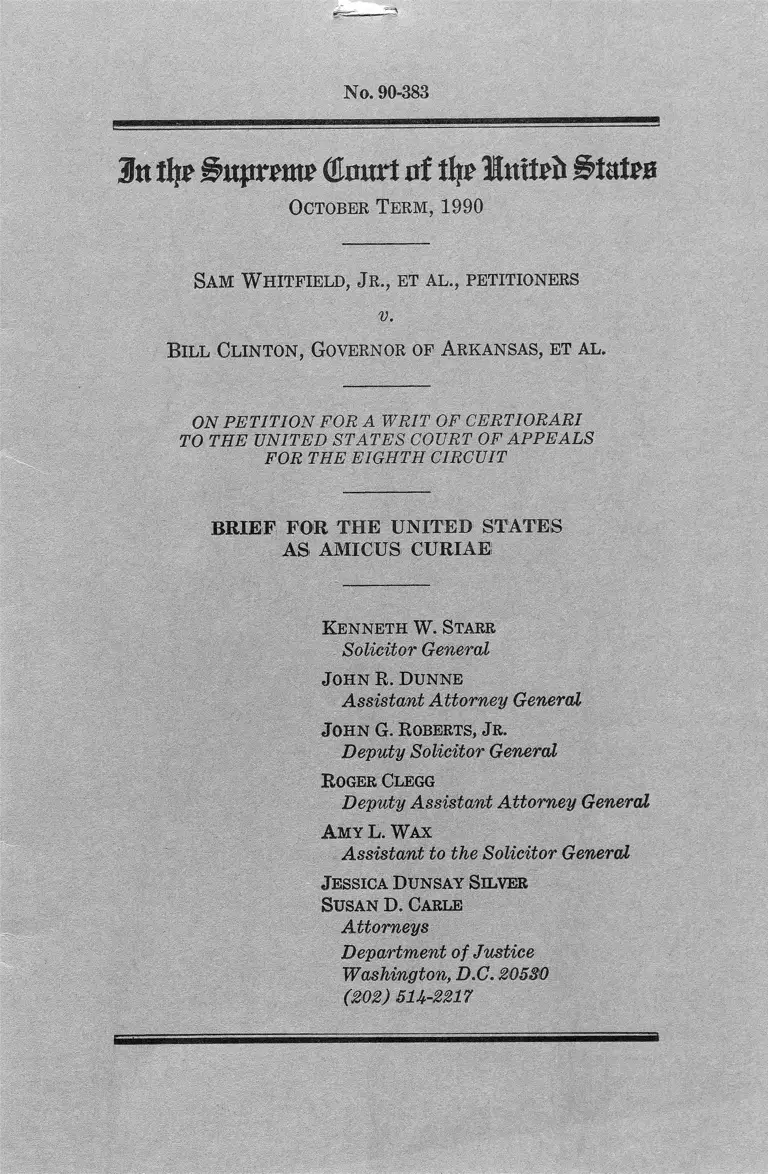

No. 90-383

In % <&mtrt ni % Mnttelt States

October Term, 1990

Sam W hitfield, Jr., et al ., petitioners

v.

Bill Clinton, Governor of A rkansas, et al.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE!

Kenneth W. Starr

Solicitor General

John R. Dunne

Assistant Attorney General

John G. Roberts, Jr.

Deputy Solicitor General

Roger Clegg

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

A my L. Wax

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Susan D. Carle

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20580

(202) 511-2217

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether black voters have standing to challenge a

state law majority vote requirement under Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973, when

they comprise 47% of the voting age population of the

jurisdiction.

2. Whether the district court erred in concluding after

trial, under the totality of the circumstances, that a state

law requirement that a party nominee win “a majority

of all the votes cast for candidates for the office in a

primary election” did not deprive black voters of rights

guaranteed under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. 1973.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement..... ...... ................ ................................... ........... 1

Discussion............ ........... .................................................. 8

Conclusion______ _______ _____ ___ ________ ____ ___ 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Butts V. City of New York, 779 F.2d 141 (2d Cir.

1985)............. ....... ................. ........... .................... 9, 17

City of Port Arthur V. United States, 459 U.S. 159

(1982) ___________ ____________ _________ ____ 13

City of Rome V. United States:

446 U.S. 156 (1980) ______ _____ _____ ....10, 11, 13, 14

472 F. Supp. 221 (D.D.C. 1979) ............. ...... .... 14

McCray v. New York, 461 U.S. 961 (1983)______ 10

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)___3, 11, 14, 15,

16, 17, 18, 19

Westwego Citizens for Better Gov’t V. Westwego,

872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989)_______ _____ ___ 19

White V. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)__________ 10, 13

Zimmer V. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff’d sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Bd. V. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976)_______ __ 10, 18

Constitutions, statutes, and rule:

U.S. Const.:

Amend. X IY _________ ______ ____ __________ 2

Amend. X V .... ......... ............... .................. ........ 2

Ariz. Const, art. 5, § l.B (Supp. 1989) _________ 8

Ark. Const, of 1874, amend. 29, § 5 (1938)....... ...... 2, 8

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973 et seq.:

§ 2, 42 U.S.C. 1973...........2, 5, 7, 8, 9,11, 12, 13, 14, 18

§ 2 (a), 42 U.S.C. 1973(a) ________________ _ 11

§ 2 (b ) , 42 U.S.C. 1973 (b )__ _____ ____ __ _ 15

§ 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c__ ______ ___________ 9,11, 12, 13

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L.

No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 131 _____________ ________

(Ill)

7-8

IV

Constitutions, statutes, and rule—Continued: Page

Ala. Code (Supp. 1990) :

§ 17-16-6___ _______ ______ ____ ____________ 8

§ 17-16-35___ _______________ _____ _________ 8

Ark. Stat. Ann. (1976) :

§§3-110 to 3-113__ ________________________ 8

§ 3-113 (Supp. 1985)............ ................ ......... . 8

§ 3-113 (c) ..... ........ .............................................. 8

§ 3-113 (d ) ...................... ................... ......... ........ 8

§ 3-113 ( i ) .............................. ............................... 8

Ark. Stat. Ann. (1987) :

§ 7-5-106.............................................................. 2, 3

§7-5-106 (Supp. 1989).......... .............................. 2

§ 7-7-202........................................ ............. ....... 2, 8

§ 7-7-203 (Supp. 1989)......................... ............. 2

Fla. Stat. Ann. (Supp. 1990) :

§ 100.061 ......... ...... .............................................. 8

§ 100.091................................ .............................. 8

Ga. Code Ann. § 21-2-501 (1987) ....... ............ ........ 8

La. Rev. Stat. (1979) :

§ 18:402 (Supp. 1990) ...................... ................. 8

§18:481......................... 8

Miss. Code Ann. § 3109 (Supp. 1989) ________ ___ 8

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 163-111 (Supp. 1990)....... ...... ...... 8

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 26 (Supp. 1990) :

§ 1-102................. ...... ................................ ........ 8

§ 1-103........ 8

S.C. Code Ann. § 7-13-50 (Law. Co-op. Supp.

1989)............. 8

Tex, Code Ann. § 13.003 (Vernon Supp. 1990)..... 8

Sup. Ct. R. 14.1 (a) ............................ ............. ........... 19

Miscellaneous:

121 Cong. Rec. 16,251 (1975)____ 12

H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975)___ 12

H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981). 12-13

S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975)........... 12

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)...........3, 12, 17

In % ̂ it|rr?me ( ta r t nf tty Hmtrfc States

October T e r m , 1990

No. 90-383

Sa m W h itfie ld , J r ., et a l ., petition ers

v.

B il l Cl in t o n , Governor op A r k a n s a s , et a l .

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF' FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

This brief is filed in response to the Court’s invitation

to the Solicitor General to express the views of the

United States.

STATEMENT

1. Phillips County is a predominantly rural, econom

ically depressed county in Arkansas. According to the

1980 census, the County has a total population of 34,772

residents of whom 53% are black. Pet. App. 6a n.l.

Blacks constitute 47% of the County’s voting age popu

lation. Ibid.

All six countywide elective offices 1 are filled through

partisan elections. No black candidate has ever been

nominated for countywide office by either the Democratic

1 These offices are sheriff, judge, treasurer, assessor, county clerk,

and circuit clerk (JX 1, at 20).

( 1 )

2

or Republican Party. Pet. App. 125a. Nor has any black

candidate won countywide office. Ibid.

Under a 1939 amendment to the Arkansas Constitu

tion (Pet. App. 66a), a party nominee must receive a

“majority of all the votes cast for candidates for the

office in a primary election.” Ark. Const, of 1874, amend.

29, § 5 (1938). See Pet. App. 7a-8a. Under the state

statute designed to implement this provision, the pri

mary process consists of a “preferential” primary elec

tion and, if necessary, a runoff “ general primary” elec

tion. Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-202 (1987). The preferential

primary is held two. weeks before the general primary.

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-203 (Supp. 1989).

In 1983, the Arkansas Legislature also enacted a run

off requirement for general elections for municipal and

county offices. Ark. Stat, Ann. § 7-5-106 (1987). Mu

nicipal offices in Phillips County are filled through non-

partisan elections. There is no primary election as such,

and a runoff is often required because the participation

of multiple candidates tends to prevent any one candi

date from obtaining a majority in the first balloting. See

Pet. App, 138a.

2. In 1986, petitioners:—describing themselves as black

residents, of Phillips County registered to vote in general

elections and Democratic primaries (Amended Compl.

2-3)— filed suit in the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Arkansas, seeking declaratory

and injunctive relief to prevent the operation in Phillips

County of Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-202 (1987) (party pri

mary runoff) and § 7-5-106 (Supp, 1989) (general elec

tion runoff). Petitioners alleged that the runoff require

ments mandated by these statutes were adopted with a

discriminatory purpose in violation of the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments, and that they operated in

Phillips County to deny black residents an equal oppor

tunity to elect the candidates of their choice in violation

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

1973.

3

Prior to trial, the district court dismissed petitioners’

challenge to the general election runoff requirement on

two alternative grounds. Pet. App, 143a. First, the

court held that petitioners lacked standing to challenge

the statute, because they failed to demonstrate that the

general election runoff requirement had harmed any

black candidates. Id. at 164a; see id. at 152a, 164a-167a.

Second, the court found that petitioners had failed to

perfect this aspect of their suit against the proper

parties.2 3

Following trial on the party primary issue, the district

court addressed the so-called “Senate Report factors.” ®

Pet. App. 83a-130a. The court found that the black pop

ulation of Phillips County constituted “ approximately

53 % of the total, and the voting age population of blacks

is only marginally less than that of the whites.” Id. at

105a.4 The court then observed that “ there has been

extreme racial polarization in voting in Phillips County,

Arkansas, in, recent years,” id. at 115a,5 and found that

2 The court held that the Phillips County Election Commission

was an indispensible party to the challenge to Section 7-5-106, and

that petitioners had failed properly to join the Commission, because

of a defect in service. See Pet. App. 132a, 143a. The court also dis

missed the Governor and Secretary of State as defendants, on the

ground that “no claim of wrongdoing ha[d] appropriately been

asserted against [them].” Id. at 155a. The court reasoned that if

the defendant county committees were required by the Voting

Rights Act to certify certain results, the Governor and Secretary of

State would have no choice but to accept those results. Ibid.

3 These are the factors identified in the Senate Report accompany

ing the 1982 amendment to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-29 (1982). See Thornburg

V. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 44 (1986).

4 The court did not cite a figure for voting age population, but

the undisputed evidence showed that 47 % of the voting age popula

tion was black. See Pet. App. 21a.

5 The court based this conclusion on evidence offered by petition

ers concerning 15 elections held in Phillips County in 1984 and 1986

in which black candidates had unsuccessfully sought election to

4

Arkansas has had a long history of official discrimination

that has affected the right of black citizens to register,

vote, and otherwise participate in the democratic process.

Id. at 114a-115a. In addition, the court found that

black residents continued to bear the effects of discrimi

nation in areas such as education, employment, and

health, which “ are more devastating in Phillips County

than in other places, because of * * * dire economic cir

cumstances.” Id. at 119a. The court observed, however,

that “ those effects should not hinder [blacks’ ] ability to

participate effectively and equally in the political proc

ess.” Ibid. The court further found that “ race has fre

quently dominated over qualifications, and issues” in elec

tions, id. at 125a, and that no black candidate had ever

been elected to countywide or state legislative office from

Phillips County. Ibid*

With regard to the state and party policies, underlying

the primary runoff requirement, the court, concluded that

they were “ not tenuous but, to the contrary, strong,

laudable, reasonable, and fair to all.” Pet. App. 130a.

Observing that “ [m]ajority rule” lies at “ the very heart

of our political system,” the court, stated that “ it must be

assumed” that the State had adopted the primary run

off requirement to vindicate that legitimate purpose. Id.

at 127a-128a. The court also expressed the conviction

that “ the elimination of the run-off would tend to per

petuate racial polarization and bloc-voting.” Id. at 129a.

The court, added (ibid.) : 6

countywide office, city office, or state legislative seats within Phillips

County. See Pet.. App. 116a-117a. Petitioners’ expert witness esti

mated that black candidates received between 86% and 100% of the

black votes cast in the elections for countywide office, but no more

than 15%— and usually much less— of the white votes. Ibid.

6 The court noted that there was little evidence on the responsive

ness of elected officials (Pet. App. 126a) or on the slating process.

Id. at 118a. It concluded that the County has not, “ in the recent

past, used any of the other ‘discrimination-enhancing’ voting prac

tices mentioned [in the Senate Report].” Ibid.

5

Each party has an objective of breaking down harm

ful divisions among its supporters. The evidence sug

gests that plurality-win statutes or rules promote

racial polarization and separation. Run-off provisions

promote communication and collaboration among the

various constituencies by which coalitions are built.

The court then dismissed petitioners’ Section 2 chal

lenge to the operation of the majority vote requirement

for party primaries in Phillips County.7 The court ex

plained that “we do not have here the minimal dispari

ties necessary to establish either whites or blacks as a

‘minority’ of the voting age population. Those popula

tions are for practical purposes equal.” Pet. App. 92a.

The court thus, ruled that “ as a matter of law, * * * the

undisputed population figures here are not such as will

permit the plaintiffs to challenge the primary runoff law

of the state- of Arkansas as a violation of Section 2.” Id.

at 107a-108a.

Although noting that it was not adopting the view that

“ section 2 does not apply to majority vote requirements

when the election at issue is for a single office,” Pet.

App. 104a-105a, the court went on to state that it had

doubts “ that runoff requirements have any identifiable

racially discriminatory effects” (id. at 97a), or “ in the

factual context revealed by the evidence, could, as a mat

ter of law, be deemed to be a device capable of making

the political processes leading to nomination less open to

participation by blacks than to others.” Id. at 105a. The

court noted that the prospects for black candidates ob

taining the party nomination under the single primary

system that petitioners seek were “ speculative]” (id.

7 The court also dismissed petitioners’ constitutional claims after

finding that petitioners’ evidence was insufficient to establish that

the primary runoff requirement was enacted and maintained with

a racially discriminatory purpose. Pet. App. 82a. Petitioners do

not seek review of that dismissal.

6

at 100a), because “ once you change the rules, then a

different dynamic obtains.” Id. at 98a.8

On the other hand, the court emphasized the importance

of the state interests at issue. The court quoted from

commentators’ views that eliminating majority vote re

quirements would weaken political parties’ chances of

nominating winning candidates, making it impossible to

predict whether adoption of a plurality vote system would

lead to the election of more black officials. Pet. App. 94a-

95a, lOOa-lQla. The court further suggested that retain

ing the majority vote requirement would probably foster

biracial coalition-building over time, and thus could be

expected to enhance black political influence in the long

run. Id. at 101a-104a, 128a-129a. Finally, the court sug

gested that invalidating majority vote requirements would

undermine the operation of democratic systems of repre

sentation because “Americans have traditionally been

schooled in the notion of majority rule. * * * [A] major

ity vote gives validation and credibility and invites ac

ceptance; a plurality vote tends to lead to a lack of ac

ceptance and instability.” Id. at 81a,

The court discounted what it recognized were its “posi

tive findings with respect to many of [the Senate Re

8 The court explained (Pet. App. 97a-98a) :

It is one thing- for the [petitioners], Mr. and Mrs. Whitfield,

to point out that, after their first primary elections, they would

have been the Democratic Party’s candidates in the general

election if they had not had to face a runoff; it is quite another

thing to state that, had there been no runoff provisions when

they ran in the primary, they would have been the Democratic

candidates for the particular offices they were seeking.

The court observed that “where racial voting and racial polariza

tion exist,” the establishment of a plurality election system “will

result in attempts to limit the number of candidates on one’s own

side and, at the same time, to attempt to increase the number of

candidates on the opposition side.” The success of black or white

candidates would therefore; turn on the “happenstance” of whether

“ the black community can agree on one candidate * * * while the

white community does not respond in kind and therefore ends up

with two or more white candidates in the race.” Id. at 98a.

7

port] factors.” Pet. App. 130a. It stated that these fac

tors had “ no tendency to prove, or disprove” a claim that

the Arkansas majority vote requirement for party pri

maries “ makes the political processes not ‘equally open

to participation’ by blacks in that blacks have ‘less op

portunity than whites to participate in the political proc

ess and to elect representatives of their choice.’ ” Ibid. ;

see also id. at 111a. In the court’s view, “ [t]he truth is

that focusing on some of the factors serves more as a

distraction than as a useful tool for evaluating the cause

and effect operation of the challenged runoff laws.” Pet.

App. 130a.

3. On appeal, a panel of the Eighth Circuit, with

Senior District Judge Hanson concurring in the result

and Senior Circuit Judge Bright dissenting, reversed.

Pet. App. 3a-42a.9 In the lead opinion by Judge Beam,

the court observed that the potential of majority vote

rules to dilute minority voting strength was well recog

nized in the case law. Id. at 18a-19a. The court also

decided that the district court had erred as a matter of

law in ruling that a Section 2 claim could not be sus

tained where blacks made up 47% of the voting age

population. Pet. App. 20a-21a. Finally, the court held

that the district court failed properly to analyze the run

off requirement “ in light of the results-oriented test ar

ticulated in the Senate Report” accompanying the 1982

9 Senior District Judge Hanson wrote separately (Pet. App. 43a-

46a) to express concern over the “ fragmentation of state law” that

would result from enjoining operation of the majority vote statute

in one county. Id. at 43a. He concluded, however, that Congress

must have intended this “natural consequence” of its amendment to

Section 2 of the Act. Id. at 44a-45a.

Senior Circuit Judge Bright dissented (Pet. App. 46a-57a) from

the holding that the majority vote requirement for party primaries

operated in Phillips County to violate the Voting Rights Act.

Judge Bright argued that the importance of thei principle of major

ity rule, its long history, and the absence of direct authority for

the position adopted in the panel opinion, counseled against in

validation of the requirement of a majority vote for party nomina

tion. Id. at 48a.

8

amendment to Section 2. Pet. App. 23a. The court con

cluded that petitioners’ evidence on the factors deemed

relevant by this Court in Gingles to a finding of vote

dilution sufficed to establish a Section 2 violation under

the totality of the circumstances. It remanded the case

to the district court for determination of a remedy. Id.

at 36a-37a, 42a.10

On rehearing en banc, the court of appeals affirmed

the judgment of the district court by an equally divided

vote, without opinion. Pet. App. 2a.

DISCUSSION

The questions whether Section 2 challenges to majority

vote requirements can be maintained, and how they should

be assessed, are important to the enforcement of the Vot

ing Rights Act by the United States. There are majority

vote or substantial plurality requirements for state offices

in eleven States 11 and for offices in numerous localities.

The United States is currently challenging certain appli

cations of the majority vote requirement under Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act, and regularly evaluates the

10 The panel upheld the district court’s dismissal of petitioners’

constitutional challenges to § 7-7-202 and amendment 29 of the

Arkansas Constitution, agreeing with the district court’s findings

that they had not been enacted with discriminatory intent. See Pet.

App. 13a-15a.

The court of appeals also upheld the dismissal of petitioners’

challenge to the majority vote statute for general elections. The

court concluded that petitioners lacked standing. Pet. App. 38a n.4.

11 See generally Ala. Code §§ 17-16-6, 17-16-35 (Supp. 1990) ; Ark.

Stat. Ann. §§3-110 to 3-113, 3-113(i), 3-113(c), 3-113(d) (1976);

Ariz. Const, art. 5 § l.B (Supp. 1989) ; Fla. Stat. Ann. §§ 100.061,

100.091 (Supp. 1990); Ga. Code Ann. § 21-2-501 (1987) ; La. Rev.

Stat. § 18:402 (Supp. 1990), § 18:481 (1979); Miss. Code Ann.

§ 3109 (Supp. 1989) ; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 163-111 (Supp. 1990) ;

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 26, §§ 1-102, 1-103 (Supp. 1990) ; S.C. Code

Ann. § 7-13-50 (Law. Co-op. Supp. 1989) ; Tex. Code Ann. § 13.003

(Vernon Supp. 1990).

9

effect of such requirements in reviewing changes sub

mitted for preclearance under Section 5, 42 U.S.C. 1973c.

These questions, however, have received limited consid

eration by the lower courts, and, as yet, have not gen

erated substantial disagreement among the circuits.12 In

addition, the inability of the en banc court of appeals to

issue an opinion in this case counsels against review by

this Court. While we think the district court erred in its

standing analysis, and while we do not share that court’s

expressed reservations about the applicability of Section 2

to the majority vote requirement at issue here, the dis

trict court, in the final analysis, did address petitioners’

Section 2 claim on the merits under the totality of the

circumstances test. That is the correct legal test; the

question whether the district court properly applied that

test to the facts before it— a matter as to which we have

significant doubts— does not warrant further review in

this Court.

We anticipate that the question of the validity under

Section 2 of particular majority vote requirements will

arise in future cases. Given the present lack of a circuit

conflict, the fact that most circuits have not addressed

12 Only the Second Circuit has ruled on whether the operation of a

party primary runoff requirement for single member offices violates

the Voting Rights Act. In Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d 141

(1985), the Second Circuit considered a challenge to a New York

statute requiring a run-off election in the party primary for city

wide office if no party candidate received more than 40% of the

vote. In deciding that there was no Voting Rights violation, a

divided panel of that court ruled that a majority vote requirement

in a primary for candidates for single-member offices was not “ the

kind of electoral arrangement[] that can violate the Act.” 779 F.2d

at 148. The majority distinguished the case of “ elections for multi

member bodies” by explaining that (ibid.)

[t]here can be no equal opportunity for representation within

an office filled by one person. Whereas, in an election to a multi

member body, a minority class has an opportunity to secure a

share of representation equal to that of other classes by elect

ing its members from districts in which it is dominant, there

is no such thing as a “share” of a single-member office.

10

the issue at all, and the fact that the only precedential

opinion in this case is that of the district court—-which

applied the correct test—we believe that the issue will

benefit from “further study” in the lower courts “before

it is addressed by this Court,” McCray v. New York,

461 U.S. 961, 963 (1983) (Stevens, J.). Accordingly,

the petition should be denied.

1. As its first alternative ground of decision, the dis

trict court held that “ the undisputed population figures

here are not such as will permit [petitioners] to chal

lenge [the state law].” Pet. App. 107a-108a. Under well-

settled precedent, the district court was wrong to hold

that black voters were too numerous in Phillips County

to maintain a Section 2 challenge to the majority vote

requirement. See Pet, App. 105a. In its seminal opinion

outlining standards for analyzing vote dilution claims,

the Fifth Circuit sitting en banc conclusively rejected the

analytical approach employed by the district court here.

See Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973),

aff’d sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Mar

shall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976). The Zimmer court reversed

district court and panel rulings that an at-large voting

system could not be said to cause vote dilution where the

total black population was 58.7%, but blacks constituted

a minority of registered voters. 485 F.2d at 1300-1301.

The court in Zimmer noted that this Court upheld a find

ing of vote dilution in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973), even though the protected group in that case

(Mexican-Americans) comprised a numerical majority in

one of the counties at issue. 485 F.2d at 1303. Reason

ing from this Court’s precedents, the Fifth Circuit con

cluded that “ access to the political process and not popu

lation [is] the barometer of dilution of minority voting

strength.” Ibid.

In this case, the undisputed figures show that blacks

constitute a minority— 47%— of the voting age popula

tion. Pet. App. 6a n.l, 21a. See, e.g., City of Rome v.

United States, 446 U.S. 156, 186 n.22 (1980) (voting age

11

population generally recognized as most appropriate in

dicator of minority voting strength). Moreover, where

past discrimination and adverse social conditions affect

access to the political process, even a black voting ma

jority might not have an equal opportunity to elect can

didates of its choice, and it is that opportunity-—not any

numerical test— that is the touchstone under the Act.

See 42 U.S.C. 1973.

The district court, however, did not rest on its ruling

that petitioners could not mount a Section 2 challenge

because of the population figures, but instead went on to

consider the merits of petitioners’ challenge.

2. a. The district court’s doubts about whether a ma

jority vote requirement can ever violate Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act run contrary to the plain language of

the statute, which provides without limitation that “ [n]o

voting qualifiation or prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure” shall be imposed or applied in a

manner that violates the Act. 42 U.S.C. 1973(a). As this

Court observed in Gingles, 478 U.S. at 43, Section 2 pro

hibits “any voting qualifications or prerequisites to voting,

or any standards, practices, or procedures which result

in the denial or abridgment of the right to vote of any

citizen who is a member of a protected class of racial

and language minorities.” The statutory language makes

no exception for majority vote requirements, either for

single member offices or other types of elected positions.

This Court has construed identical language in Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act—which covers changes to “ any

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting,” 42 U.S.C.

1973c— to apply to majority vote requirements. See City

of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. at 184.13

13 The Attorney General, in the exercise of his preclearance re

sponsibilities under Section 5, has frequently objected to changes

replacing a plurality-win rule with a majority vote requirement,

and Congress was well aware of this longstanding administrative

interpretation when it amended Section 2 in 1982. The Attorney

12

Section 2 goes on to provide that a violation is estab

lished if, “based on the totality of circumstances,” it can

be demonstrated that a “ political process [] leading to

nomination or election” operates to deprive protected mi

norities of equal opportunity to “participate in the politi

cal process and to elect representatives of their choice.”

Once again, the statute does not categorically limit the

types of “ political processes” that might be challenged as

preventing minorities from electing “ representatives of

their choice.” The words simply contain no exception for

majority vote requirements.14 And there is no theoretical

General’s administrative interpretation comports with the legisla

tive history of Section 5. In extending Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act to Texas in 1975, Congress focused specifically on the

extensive use in that State of majority vote requirements, coupled

with other dilutive election devices, to halt the growing political

influence of Mexican-American and black voters. See, e.g., S. Rep.

No. 295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 27 (1975) (describing amendment of

city charter to replace plurality-win rule with majority run-off

system after black almost won election, and noting extensive use of

at-large structures with accompanying majority run-offs in largest

Texas cities) ; H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 18-20

(1975) (sam e); 121 Cong. Rec. 16,251 (1975) (remarks of Rep.

Edwards).

14 Nor does the legislative history give any indication that Con

gress intended to provide such an exception. To the contrary, that

history suggests that Congress regarded majority vote rules as an

electoral device having the potential to dilute the minority vote.

See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 417, supra, at 6 (listing “majority runoffs” as

one of “a broad array of dilution schemes * * * * employed to cancel

the impact of the new black vote” ) ; id. at 10 (frequency of Section

5 objections to majority vote requirements “ reflects the fact that

* * * covered jurisdictions have substantially moved * * * to more

sophisticated devices that dilute minority voting strength” ) ; id.

at 22, 29, 30 (listing the presence of a majority vote requirement

as a factor to be considered under the totality of the circumstances

test in light of its potential to enhance discrimination) ; id. at 30

(although prior case law dealt with “ electoral system features such

as at-large elections, majority vote requirements and districting

plans * * * Section 2 remains the major statutory prohibition of all

voting rights discrimination” ) . See also H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th

13

or empirical reason why a majority vote requirement can

not operate-—under certain circumstances— to afford a

protected class less opportunity to participate in the elec

toral process or to elect its chosen candidate.

Nothing in this Court’s decisions precludes a finding

that a majority vote rule, under the totality of the cir

cumstances, may operate to dilute the vote of a protected

class in violation of Section 2. In White v. Regester,

supra— a case considering the constitutionality of a mul

timember districting scheme that the district court found

was used invidiously to dilute minority voting strength

— this Court found “no reason to disturb” a district

court’s findings that a majority vote prerequisite to nom

ination in primary elections “ enhanced the opportunity

for racial discrimination.” 412 U.S. at 766. In City of

Port Arthur v. United States, 459 U.S. 159 (1982), in

considering a Section 5 challenge to the expansion of the

City’s borders that resulted in decreased minority voting

strength, the Court upheld the district court’s elimina

tion of the majority vote requirement for certain at-large

positions on the city council. The Court observed that

“ [i]n the context of racial bloc voting prevalent in

[the municipality], the [majority vote] rule would

permanently foreclose a black candidate from being

elected to an at-large seat. Removal of this require

ment, on the other hand, might enhance the chances

of blacks to be elected to the two at-large seats.” Id. at

167-168. Finally, in City of Rome v. United States,

supra— another Section 5 case— the Court acknowledged

that a general election majority vote requirement, in

combination with extreme racial bloc voting, “ signifi

cantly decreased the opportunity for * * * a Negro can

didate since, ‘even if he gained a plurality of votes in the

general election, [he] would still have to face the runner-

up white candidate in a head-to-head runoff election in

which, given bloc voting by race and a white majority,

Cong., 1st Sess. 18 (1981) (potentially discriminatory elements of

election process include “majority vote run-off requirements” ).

14

[he] would be at a severe disadvantage.’ ” 446 U.S. at

184 (quoting 472 F. Supp. 221, 244 (D.D.C. 1979)). All

of these statements belie the district court’s suggestion

that a majority vote requirement is not an electoral ar

rangement that can result in minority vote dilution in

violation of the Act.

b. In Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 46-47 n.12,

this Court established an analytic framework for deter

mining whether a particular voting practice can operate

to deprive a protected class of rights under Section 2.

While the Court took care to note that it was not decid

ing whether the standards developed in that case for

assessing whether multimember districts violated Sec

tion 2 applied to; challenges to other electoral arrange

ments, we believe that those standards are applicable in

the present context.

According to Gingles, the challenged practice generally

must satisfy three “ necessary preconditions.” 478 U.S.

at 48-51. Petitioners have plainly satisfied two of the

Gingles preconditions.—proof of polarized voting, includ

ing substantial minority cohesion, and white bloc voting

against minority-preferred candidates denying electoral

success to those candidates. See id. at 48-49 n.15, 51.

The level of political cohesiveness among black voters in

countywide elections in Phillips County is at least as

high as that which this Court described as “ overwhelm

ing” in Gingles, id. at 59. Likewise, the degree of white

bloc voting against minority candidates in elections for

countywide office is significantly greater than that ob

served in Gingles, compare id. at 80-81 with Pet. App.

116a-117a, and is sufficient to result consistently in the

defeat of black candidates for nomination under the run

off system. In addition, black candidates have never won

party nomination to countywide office. Black voters, al

though constituting 47% of the voting age population,

have so far been unable to elect the candidates of their

choice.

To satisfy the remaining Gingles precondition, plain

tiffs must establish that minority voters would have an

15

enhanced “potential to elect representatives in the ab

sence of the challenged structure or practice.” 478 U.S.

at 50 n.17. To challenge a majority vote requirement for

party primaries, however, plaintiffs need not show a

potential to elect; they need only show the potential to

nominate candidates of their choice in a system that does

not employ such a rule. The statutory language ex

plicitly provides that a violation is established if, inter

alia, “ the political processes leading to nomination * * *

are not equally open to participation by members of a

class of citizens protected by” the Act. 42 U.S.C.

1973(b) (emphasis added). Thus, in order to show an

injury capable of redress under the Act, plaintiffs must

establish only that success is possible at the stage of the

political process under challenge.15

The Court in Gingles, 478 U.S. at 50 & n.17, also indi

cated that the potential for success may be established

in theory; it is not necessary to demonstrate, for exam

ple, that particular minority-supported candidates would

have won specific past elections if the challenged prac

tice had not been in place, nor that minority-supported

candidates are sure to win in the future. Although peti

tioners in this case cannot prove that candidates sup

ported by black voters are certain to do better under a

plurality-win nomination system, they can demonstrate

that, even at the extreme levels of racial bloc voting in

Phillips County, those candidates have at least the poten

tial to gain nomination if the majority vote requirement

is abolished. For example, because blacks constitute more

than one-third of the voting age population, a minority

supported candidate might be able to win the nomination

if two non-minority-backed candidates run against the

15 In dismissing petitioners’ claim with regard to the nomination

process, the district court therefore erred to- the extent that it

relied on petitioners’ failure to establish that minority-backed candi

dates could win the general election if they succeeded in gaining

nomination in the primaries. See Pet. App. 94a-95a, lOOa-lOla.

16

minority’s candidate; the same would not be true if a

runoff took place.

The district court therefore erred in concluding that

petitioners’ claims of redressable injury were too specu

lative because candidates supported by non-minorities

might refrain from running against each other to mini

mize minority success under a plurality-win system.

This reasoning is contrary to the approach in Gingles,

which does not require petitioners to show that they will

succeed in winning nomination under every possible

scenario. Rather, the relevant question is whether, if the

challenged practice is eliminated, it is possible for mi

nority supported candidates to succeed.

c. After the three-part threshold test is satisfied, the

Gingles framework calls for an assessment under the

‘“ totality of the circumstances” of the effect of the prac

tice in a particular locale on the opportunity of protected

groups to “participate in the political process and to

elect representatives of their choice.” This assessment is

based on a consideration of all relevant factors appro

priately tailored to take into account the nature of the

challenged practice. In considering the effect of these

factors on minority voting strength, the court must en

gage in a “ searching practical evaluation of the ‘past and

present reality,’ ” Gingles, 478 U.S. at 45 (quoting S.

Rep. No. 417, supra, at 30).

The district court, “ assuming Section 2 would apply to

runoffs” under the circumstances before it, concluded

that “ the proof does not sustain [petitioners’ ] contention

that the challenged provisions result in [petitioners] and

other blacks having less opportunity to participate in the

political process or to elect candidates of their choice.”

Pet. App. 131a. The court ruled that petitioners “have

not proved or demonstrated by the evidence that [the

majority vote] provision, based on the totality of the cir

cumstances revealed by the evidence in this case, has had,

or has, the effect of discriminating against blacks or that

there is any causal connection between the lack of black

17

electoral success and the challenged runoff procedure.”

Id. at 108a.

We have serious doubts that the district court cor

rectly applied the totality of the circumstances test. For

example, the district court seemed to ascribe nearly con

trolling weight to the “underlying policy” factor under

the totality of the circumstances. Cf. Gingles, 478 U.S.

at 45. The district court characterized the “majority

win” principle as a fundamental tenet of democratic sys

tems, and suggested that departure from that principle

invites “ lack of acceptance and instability.” See Pet.

App. 80a-81a; see also id. at 48a. (court of appeals opin

ion of Bright, J., dissenting in part) ; Butts, 779 F.2d at

149. Majority vote requirements at the nomination stage

have also been justified as a means to avoid the “ fluke”

election of candidates far from the political mainstream,

see id. at 143, or as a way for political parties to maxi

mize the appeal of their nominee to the general elec

torate. See Pet. App. IGOa-lOla.

A majority vote rule at the party primary level may

well be advantageous to the party and tend to promote

stability in the democratic process. However, the dis

trict court’s characterization of the majority vote re

quirement as a fundamental democratic tenet is over

drawn in this context. Plurality-win primaries for state

and local offices are widespread, and represent the pre

dominant system in state governments nationwide. The

common and longstanding use of this arrangement ne

gates the premise that a majority vote rule at the pri

mary stage is an indispensable component of our demo

cratic system.16

Thus, while we fully agree that legitimate reasons

exist for adopting a majority vote system— either at the

primary or the general election phase— and that those

16 Cf. S. Rep. No. 417, supra, at 29 n.117 ( “even a consistently

applied practice premised on a racially neutral policy would not

negate a plaintiff’s showing through other factors that the chal

lenged practice denies minorities fair access to the process” ).

18

reasons should be properly weighed under the totality of

the circumstances, those reasons do not trump all other

factors or combination of circumstances to render the

practice automatically valid under Section 2. The use of

multimember districts, for example, may advance legiti

mate goals, see, e.g., Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d at

1301 (at-large scheme insures fidelity to one-person, one-

vote principle), but multimember districts may nonethe

less operate to violate Section 2. There is no reason for

a different approach to the majority vote rule: the statu

tory language and legislative history of Section 2 make

clear that Congress did not intend to provide an exemp

tion for majority vote requirements simply because good

things could be said for them.

At the same time it was according nearly controlling

weight to the sound policies underlying the challenged

practice, the district court minimized the significance of

what it acknowledged were “ positive findings with re

spect to many of [the Senate Report] factors.” Pet.

App. 130a. The court should not have so readily dis

missed its findings that “race has frequently dominated

over qualifications and issues” in elections (id. at 125a),

that there is a long history of official discrimination in

voting (id. at 114a-115a), that Phillips County is char

acterized by extreme racial bloc voting (id. at 116a-117a),

and that black residents of Phillips County suffer from

a legacy of racial discrimination. Id. at 119a, 123a.

Rather, all those factors should have been considered—

together with the policy underlying the challenged law—

in a more “ searching practical evaluation” of the sort

mandated by this Court in Gingles. 478 U.S. at 45.

3. The district court dismissed petitioners’ challenge

to the general election majority vote requirement on two

alternative grounds: failure to join an indispensable

party, and lack of standing or ripeness. Although peti

tioners seek review of the first ground (see Pet. i i ) , it is

19

plainly fact-specific:—relating to a defect in service of

process (Pet. App. 143a-144a)— and does not warrant

review by this Court. Petitioners do not include a “ques

tion presented” on the second ground, the standing or

ripeness issue. See Sup. Ct. R. 14.1(a).11 This is a fur

ther reason to deny review, since the two grounds are

alternative bases for the district court’s decision.18

17 Petitioners state in a footnote to the text of their petition that

this “ alternative ground for dismissal * * * squarely conflicts with

congressional intent, Gingles and decisions of other circuits.” Pet.

48 n.20.

18 In our view, the district court erred in dismissing petitioners’

challenge to the general election majority vote requirement for lack

of standing or “ ripeness.” Pet. App. 143a, 163a-167a. Petitioners

have standing as black citizens who reside in Phillips County and

are registered to vote in general elections. See Amended Compl.

2-3; see also Pet. App. 161a-162a. Therefore, the fact that there

were no minority candidates who would have won in the absence of

a majority vote requirement is not an automatic bar to standing.

See, e.g., Gingles, 478 U.S. at 57 n.25 (recognizing that minority

group may “have never been able to sponsor a candidate” ) ; West-

wego Citizens for Better Gov’t v. Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201, 1208-

1209 (5th Cir. 1989) (plaintiffs not precluded from challenging

elections for office where no black candidate had run).

20

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted.

K enn eth W. Starr

Solicitor General

John R. D unne

Assistant Attorney General

John G. R oberts, Jr .

Deputy Solicitor General

R oger Clegg

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

A m y L. W ax

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Jessica D unsay Silver

Susan D. Carle

Attorneys

F ebruary 1991

U . S . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE; 1 9 9 2 8 2 0 6 2 0 3 5 3