Walker v. City of Birmingham Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Brief for Respondent, 1966. a8a5e259-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/901a65e1-d0e7-422d-8ec9-d57bc3b43ed3/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

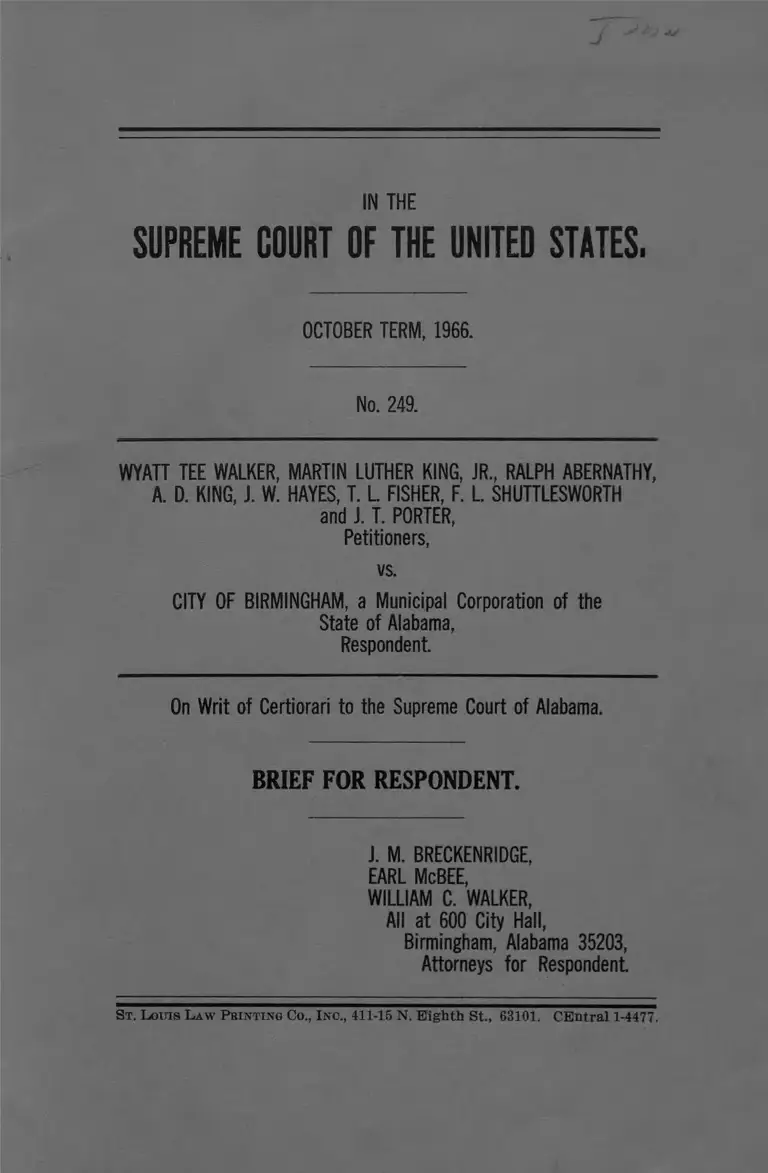

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1966.

No. 249.

W YATT TEE WALKER, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., RALPH ABERNATHY,

A. D. KING, J. W. HAYES, T. L. FISHER, F. L. SHUTTLESWORTH

and J. T. PORTER,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, a Municipal Corporation of the

State of Alabama,

Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

J. M. BRECKENRIDGE,

EARL McBEE,

WILLIAM C. WALKER,

All at 600 City Hall,

Birmingham, Alabama 35203,

Attorneys for Respondent.

St. L outs L a w Printing Co., I nc ., 411-15 N. Eighth St., 63101. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Preliminary statement concerning “ questions pre

sented” as stated by petitioners ............................... 1

Questions presented ........................................................ 3

Alabama Constitution, Statutes and Birmingham Or

dinances involved ........................................................ 6

Statement ........................................................................... 7

A. The verified injunction bill ................................. 7

B. The petition for rule nisi ..................................... 11

C. Evidence ................................................................... 13

D. Treatment by lower courts ................................... 18

Summary of argument .................................................... 21

Argument ........................................................................... 29

I. The convictions should be affirmed on the rule of

Howat v. Kansas and Mine Workers without

reaching constitutional issues concerning Ordi

nance 1159 ............................................................... 29

A. The Alabama court had jurisdiction to deter

mine its jurisdiction.......................................... 35

B. The principle above stated in I has been ap

plied in cases involving First and Fourteenth

Amendment freedoms ...................................... 39

C. Respect for the law and the courts of the land

is fundamental to the protection of minori

ties and majorities alike, without it no con

stitutional rights can endure ........................... 44

11

II. Aside from violation of Ordinance 1159 the con

tempt conviction should be affirmed on the

basis of other unlawful conduct in violation of

the injunction......................................................... 48

A. The conduct of petitioners was otherwise

unlawful ........................................................... 48

B. Such unlawful conduct is not constitution

ally protected nor immunized from punish

ment for contempt by the fact that 1159 in

part supported the injunction ....................... 50

C. The scope and purpose of the injunction was

to preserve law and order. They adequately

support the contempt convictions ................. 52

D. The evidence is sufficient ............................... 61

E. Conviction sustainable on conspiracy charge 61

III. The constitutionality of 1159 ............................. 63

IV. Statements and news release made by Petition

ers Walker, King, Abernathy and Shuttles-

worth cannot be isolated from their direct part

in the violation of the injunction to stand as

protected free speech ............................................. 66

V. The conviction of Petitioners Hayes and Fisher

is sustained by the evidence.................................. 72

Conclusion ......................................................................... 74

Appendix ......................................................................... 75-85

AUTHORITIES CITED.

Cases:

Allen v. United States, 1922 (C. C. A. 7), 278 Fed.

429 .............................................................................. 23

Amalgamated Association of St. Elec. Ry. & Motor

Coach, etc. v. Wisconsin Employment Relations

Board, 340 U. S. 383, 71 S. Ct. 359, 95 L.

Ed. 364 .....................................................................32,33

I ll

Avent v. North Carolina, 373 U. S. 375, 83 S. Ct.

1311 (May 20, 1963) ................................................

Berman v. U. S., C. C. A. Okl., 76 F. 2d 483, cer

tiorari denied, 55 S. Ct. 914, 295 U. S. 757, 79

L. Ed. 1699 ...............................................................

Blake v. Nesbet, 1905, 144 Fed. 279, 283, 284 ........

Blumenthal v. United States, 332 F. S., pages 539,

559, 68 Snp. Ct. 248, 257 ...........................26,27,61,

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 .........................

Carter v. United States, 1943, 5th Cir., 135 Fed.

2d 858 .......................................................................22,

City of Darlington v. Stanley, 1961, 239 S. C. 139,

122 S. E. 2d 207 ....................................................65,

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 86 S. Ct. 1800, 384

U. S. 808, 1966 .........................................................

City of New Orleans v. Liberty Shop, 1924, 157 La.

. . . , 101 So. 797 ........................................................

Clarke v. Fed. Trades Comm., 128 Fed. 2d 542 . . . .

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clemmons, 1963

(C. C. A. 5), 323 Fed. 2d 54, 58, 64 ..................... 26,

Coosaw Mining Co. v. South Carolina, 144 U. S. 550,

567, 12 S. Ct. 689, 36 L. Ed. 537 .............................

Cox v. State of Louisiana, 1965, 379 U. S. 536, 554,

85 S, Ct. 453, 464 .............................23,25,26,45,50,

Cox v. State of New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 61

S. Ct. 762, 85 L. Ed. 1049 .................................... 50,

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367, 67 S. Ct. 1249 ........

Dennis v. United States (1951), 341 U. S. 494, 528,

71 S. Ct. 857, 877 ......................................................

Duplex Printing Press Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S.

443, 465, 41 S. Ct. 172, 176, 65 L. Ed. 349, 16

A. L. R. 196 .............................................................

Ex P. Tinsley, 37 Tex. Cr. 517, 40 S. W. 306 . . . . 25,

Ex Parte Hacker, 250 Ala. 64, 33 So. 2d 324. .21, 23, 38,

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 ............... 28,

8

62

36

68

70

,36

,66

33

26

23

59

54

54

65

71

48

62

52

43

73

IV

Fox v. Washington, 326 U. S. 273, 35 S. Ct. 383,

59 L. Ed. 573 ........................................................... 69

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 IT. S. 64, 85 S. Ct. 209 .. 71

Giboney v. Empire Ice and Storage Company, 336

U. S. 490, 502, 69 S. Ct. 684, 691, 93 L, Ed. 834 . . . 68

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374, 83 Sup. Ct.

1311 (May 20, 1963) ................................................ 8

Gompers v. Bucks Stove & Range Co., 1911, 221

U. S. 418, 450, 31 Sup. Ct. 492, 501, 55 L. Ed. 797,

34 L. R. A. (U. S.) 874 .................................... 23,45,69

Griffin v. Congress of Racial Equality, 1963, 221

Fed. Supp. 899 ........................................................26,59

Holt v. Virginia, 381 IT. S. 131, 85 S. Ct. 1375 ........ 71

Hotel and Restaurant Employees, etc. v. Greenwood,

249 Ala. 265, 30 So. 2d 696, Cert. Den. 322 U. S.

847, 68 S. Ct. 349 .........................................21,23,38,42

Howat v. Kansas, 258 H. S. 181 . . . .20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 29,

31, 33, 35, 39, 43, 44, 47, 51, 63, 64

In Re: Debs, 158 U. S. 564, 15 S. Ct.

900 ................................................ 23,24,26,28,53,56,57

In Re Green, 369 U. S. 689, 693 ................. 20,21,31,32

In Re Landau, 243 N. Y. S. 732, 230 App. Div. 308,

app. dismissed 255 N. Y. 567, 175 N. E. 316 . . . .25, 52

In re Sawyer, 360 U. S. 622, 629, 79 S. Ct. 1376,

1379 ............................................................................ 69

In re Williams, 26 Pa. 9, 67 Am. Dec. 374 ............. 22

John Mitchell et al. v. Hitchman Coal & Coke Com

pany, 214 Fed. 685, 131 CCA 425 ........................... 41

Jones v. Securities and Exchange Comm., 298 U. S.

1, 56 Sup. Ct. 654, 80 L. Ed. 1015, 1021, 1022 . . . . 22

Kaner v. Clark, 108 111. A. 287 ...............................25, 52

Kelly v. Page, 1964 (C. C. A. 5), 335 Fed. 2d 114. .26,60

Liquor Control Commission v. McGillis, 1937, 91

Utah 586, 65 Pac. 2d 1136 .................................... 25,52

Local 333 B, United Marine Division of Int. Long

shoremen Assn. v. Commonwealth of Virginia,

V

1952, 193 Ya. 773, 71 S. E. 2d 159, cert, denied, 344

U. S, 893, 73 S. Ct. 2 1 2 ............................................

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, 83 Sup. Ct.

1122 .............................................................................

Main Cleaners & Dyers v. Columbia Super Cleaners,

332 Pa. 71, 2 A. 2d 700 ........................................

Milk Wagon Drivers Local Union v. Meadowmoor

Dairies, 312 U. S. 287, 61 S. Ct. 552, 85 L. Ed.

836 ............................................................................ 28,

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 84 S.

Ct. 710 .......................................................................

Patterson v. Colorado, 205 D. S. 454, 27 S. Ct. 556,

558 ..........................................................................

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331, 66 S. Ct. 1029

People v. McCrea, 6 N. W. 2d 489, 303 Mich. 213,

cert, denied 318 U. S. 783, 63 S. Ct. 851, 87

L. Ed. 1150 ...............................................................

People v. Tavormina, 1931, 257 N. Y. 184, 177 N. E.

317 ...............................................................................

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, 83

Sup. Ct. 1119 (May 20, 1963) ................................

Poliafico v. United States, 237 Fed. 2d 97, 104 (C. A.

6, 1956); cert. den. 352 U. S. 1025, 77 S. Ct. 590,

1 L. Ed. 2d 597 .......................................... 26,27,61,

Portland R. L. and P. Co. v. Railroad Commission,

229 U. S. 397, 33 S. Ct. 829, 57 L. Ed. 1248 ........28,

Poulos v. State of New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395,

73 S. Ct. 760, 768, 97 L. Ed. 1105, 30 ALR

2d 987 .........................................................................

Reid v. Independent Union A. W., 200 Minn. 599,

271 N. W. 300, 120 ALR 297 .................................

Schwartz v. United States, 1914 (0. C. A. 4), 217

Fed. Rep. 866 ......................................................... 23,

Shipp v. United States, 1906, 203 U. S. 563, 27 S. Ct.

165, 51 L. Ed. 319, 8 Ann. Cas. 265 ............. 22, 35,

39

8

22

i 73

71

71

71

68

62

8

68

74

65

22

40

36

VI

Short v. United States, 1937 (CCA-4), 91 Fed. 2d

614 ..............................................................................

Shuttlesworth v. City, 43 Ala. App. 68, 180 So.

2d 114 .........................................................................

Sima. Piano Company v. Fairfield, 103 Wash. 206,

174 Pac. 457 .............................................................

Skelly v. U. S., C. C. A., Okl., 76 F. 2d 483, cer

tiorari denied, 55 S. Ct. 914, 295 U. S. 757, 79

L. Ed. 1699 ...............................................................

State ex rel. Carroll v. Campbell et al., 25 Mo.

App., loc. eit. 639 ....................................................

Stanb v. City of Baxley, 1958, 355 U. S. 313, 78 S.

Ct. 277, 2 L. Ed. 2d 319 ..........................................

Stoll v. Gottlieb, 305 U. S. 165, 171, 172, 59 Sup.

Ct. 134, 83 L. Ed. 104, 108, 109; 38 Am. Banks,

U. S. 79 ...................................................................

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 367-368 . . . .

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .........................

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 529 .......................

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 60 S. Ct. 736

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 80 S. Ct. 624,

4 L. Ed. 2d 654 ....................................................... 28,

United States v. Barnett, 1964, 376 U. S. 681, 697,

84 S. Ct. 984, 993 ..................................................

United States v. Debs, C. C. 111., 64 Fed. 724, error

denied, In Re Debs, 159 U. S. 251, 15 S. Ct. 1039 ..

United States v. Parton, 1947 (CCA-4), 132 Fed. 2d

886, 887 .....................................................................26,

United States v. Rosenberg (C. C. A. 2, 1952), 195

Fed. 2d 583, 600, 601, cert, denied, 344 U. S. 838,

73 S. Ct. 20, 21, 97 L. Ed. 652, reh. denied, 344

U. S. 889, 73 S. Ct. 134, 180, 97 L. Ed. 687, reh.

denied, 347 U. S. 1021, 74 S. Ct. 860, 98 L. Ed.

1142, motion denied, 355 U. S. 860, 78 S. Ct. 91,

L. Ed. 2d 67 ......................................................26,27,

62

27

22

62

37

63

22

71

71

71

39

73

24

23

54

68

V l l

United States v. United Mine Workers of America,

330 U. S. 308 . . . .20, 21, 23, 24, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41,

43, 44,47, 51, 63,64

United States v. U. S. Klans, Knights of Ku Klux

Klan, Inc., 1961, 194 Fed. Supp. 897 ................... 26,60

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 397, 47 S. Ct. 641,

71 L. Ed. 594 ........................................................... 28,73

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287, 291, 293 71

Wood v. Georgia, 375 U. S. 375, 386, 82 S. Ct.

1364, 1372 ................................................................. 70

Statutes:

Alabama Constitution of 1901, Section 144 .............. 6

City of Birmingham Ordinance 1159 ............ 2,26,27,63

Code of Alabama, 1940, Title 7:

Section 1038 ............................................................. 6

Section 1039 ............................................................. 6

Code of Alabama, 1940, Title 36, Section 5 8 ........6,49

Code of Alabama, 1940, Title 37, Sections 505 and

506 ......................................................................6,26,49

General City Code of Birmingham, 1944:

Section 311 ......................................................... 6,26,49

Section 804 ............................................................... 6, 49

Section 1142 ............................................................. 6

Section 1231 ............................................................. 6

Section 1357 ............................................................. 6

Traffic Code of City of Birmingham, Articles III

and X .....................................................................6,49

Rules:

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 47 ........................6,22,38

Supreme Court Rule 40 l.d (2 ) ................................... 3

Miscellaneous:

10 American & Eng. Enc. of Pleading & Practice.. 37

Birmingham News, July 16, 1966 ............................. 47

Birmingham News, July 24, 1966 ............................. 47

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1966.

No. 249.

W YATT TEE WALKER, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., RALPH ABERNATHY,

A. D. KING, J. W. HAYES, T. L. FISHER, F. L. SHUTTLESWORTH

and J. T. PORTER,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, a Municipal Corporation of the

State of Alabama,

Respondent

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT CONCERNING

“ QUESTIONS PRESENTED” AS STATED

BY PETITIONERS.

We think the “ Questions Presented” by petitioners are

couched in language that fails to take into account the

full scope of the unlawful activity charged in the bill of

complaint and the activity prohibited by the injunction,

violation of which was charged in the contempt petition

and for which petitioners were convicted. Specifically,

the resolution of the problem into that of whether or not

the Birmingham Ordinance 1159 is unconstitutionally

vague or that the injunction must necessarily be tested

by the constitutionality of such ordinance, or that such

injunction or the ordinance is over broad and vague as

a censorial regulation of free speech as stated in (1) and

(2) its several subsections and (3), we think too narrowly

defines the issues, which must take into account the full

nature and extent of the unlawful conduct imminently

threatening the safety of lives and property of citizens

of Birmingham complained of in the bill of complaint

and enjoined and charged in the contempt petition rather

than to confine them solely to the mere question of

whether a peaceful, lawful parade or procession is con

verted into an illegal act simply by the fact that no per

mit was ever obtained to stage such assumedly peaceful,

lawful parade.

The approach taken by petitioners with respect to the

above, and also as to (4), which attempts to isolate the

defiant statements and news release of petitioners, M. L.

King, Jr., Abernathy, Walker and Shuttlesworth from its

place in the chain of events in consummation of the con

spiracy which brought about and culminated in the com

mandeering of the public streets of Birmingham by a

throng of some fifteen hundred to two thousand Negroes,

occupying the entire width of the pavement and extend

ing over both sidewalks for a destination which its lead

ers wilfully refused to disclose to law enforcement officers

and which formed a howling, violent, rock throwing mob,

inflicting personal injury and damage to property over

looks the conviction of all eight petitioners for conspiracy

to violate the injunction.

As to (5) the issue presented by petitioners leaves out

of account relevant matters.

— 2 —

It is also to be noted that 2 (c) does not appear to be

included in the Questions Presented in the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari.1

We, therefore, respectfully restate the questions per-

sented as we conceive them to be.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

I.

Whether the State Supreme Court properly invoked the

doctrine that a court of general jurisdiction having full

jurisdiction over the parties and with equity jurisdiction

to grant injunctions, and having done so in a controversy

over which it had jurisdiction to examine into and make

a final determination, may punish one in criminal con

tempt who wilfully, flagrantly, intentionally flouted and

defiantly violated such injunction without making any

effort to dissolve or discharge such injunction in orderly

process of law.

II.

Whether in a collateral certiorari proceeding one who,

without resorting to the lawful means available to test

the authority of such court, has arrogated unto himself

the right to contemptuously defy its order, and in the

same defiance has openly avowed his intent to violate it

and all other laws which he may decide are unjust, may

nevertheless be entitled by petition for certiorari to re

verse his conviction for criminal contempt rendered in a

proceeding in which he has been granted a full hearing,

with no failure to comply with procedural requirements:

on the alleged invalidity of the injunction for vagueness;

on the alleged invalidity of Sec. 1159 of the City Code of

— 3 —

1 This is in conflict with Supreme Court Rule 40 l.d (2).

— 4 —

Birmingham; on account of alleged exclusion of evidence;

and on account of the alleged failure of evidence to show

a violation of a particular one of the many prohibitions

of the injunction, such particular prohibition which he

denies having violated having been selected from the

many by petitioner himself?

m .

Whether one, referred to in II above, and IV below,

who has been convicted for criminal contempt for par

ticipating in a conspiracy to violate an injunction where

the conspiracy has been successful and the injunction

violated in at least one of its prohibitions, especially in

commandeering and unlawfully taking over the streets

and sidewalks of the City by a horde which formed a

violent mob, and where the sentence is the same for each

of the convicted conspirators, may attack the conviction

by isolating the act or acts done by such conspirator from

its or their place in furtherance of the consummation of

the conspiracy and apply constitutional claims of viola

tion of freedom of speech and assembly, equal protection

of the laws and lack of due process to the separate acts

so as to reverse his conviction if any of such acts in the

chain so separately treated is vulnerable to such consti

tutional attack?

IV.

Whether one who is a member of, or a member and also

an officer in and leader of an organization, Southern

Christian Leadership Conference (S. C. L. C.), or of its

affiliate organization, Alabama Christian Movement for

Human Rights (A. C. M. H. R.), against both of whom,

their members and leaders, an injunction has been issued,

and who is charged in the petition for rule nisi with

conspiring with other members or leaders to defy and

— 5 —

violate the injunction by a series of declarations and acts,

may, after conviction for a single offense, isolate such

declarations from such acts in consummation of the con

spiracy, and claim for such declarations the constitutional

immunity of free speech with effect of reversing the con

tempt conviction on certiorari proceedings?

V.

Whether or not two particular members of such organi

zation (A. C. M. H. B.), J. W. Hayes and T. L. Fisher,

both of whom attended, and one of whom (Hayes) ap

peared on its program on Saturday night, April 13th,

when solicitation for and plans were made to congregate

such unruly violent mob on Easter Sunday, April 14th,

and both of whom having admitted knowing about the

injunction and were aware that those participating in

such event on April 14th would likely be arrested, and as

to one of them (Hayes) an admission that he did so in

the face of the injunction, are entitled to reversal of their

convictions for want of proof of intent to violate the in

junction with notice or knowledge of its terms?

6

ALABAMA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND

BIRMINGHAM ORDINANCES INVOLVED.

Appendix

Pages

Alabama Constitution of 1901, Section 144 and Code

of Alabama of 1940, Title 7, Sections 1038, 1039

(Quoted in Alabama Supreme Court Opinion, R.

439) (Relating to Circuit Court Jurisdiction) ----- 75

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 47, Code of Alabama,

Recompiled 1958, Title 7 (Relating to Review of

Decrees Involving Injunctions) ................................ 76-77

Code of Alabama of 1940, Title 36, Section 58, Para

graphs 14 (a) and (b); 15 (a) and ( b ) ; 16 (a), (b)

and (c); 18; 19 (a) and (b) (Relating to Use of

Streets and Highways) ...............................................77-79

Code of Alabama of 1940, Title 37, Sections 505 and

506 (Authorizing Cities and Towns to Restrain Pub

lic Nuisances) ..............................................................79-80

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, Sections

1142, 1231 and 1357, and Traffic Code of the City of

Birmingham, Article III, Sections 3-1 (a) and (b);

3-2; 3-3; and Article X, Sections 10-3; 10-4; 10-5 (a ) ;

10-6 (a), (b) and (c) ; 10-8 (a) (Relating to Use of

Streets and Sidewalks) ...............................................80-81

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, Section 804

(Relating to Public Nuisances), and Section 311

(Relating to Breach of Peace) ................................. 82-83

— 7 —

STATEMENT.

We feel some important parts of the Record have been

omitted from petitioners’ statement.

A. The Verified Injunction Bill.

The verified bill of complaint for injunction, temporary

and permanent, was filed April 10, 1963. In paragraph 3,

it alleges that on numerous dates in April, 1963, re

spondents

“ sponsored and/or participated in and/or conspired

to commit and/or to encourage and/or to participate

in certain movements, plans or projects commonly

called ‘ sit-in’ demonstrations, ‘ kneel-in’ demonstra

tions, mass street parades, trespasses on private

property after being warned to leave the premises

by the owners of said property, congregating in mobs

upon the public streets and other public places, un

lawfully picketing private places of business in the

City of Birmingham, Alabama; violation of numerous

ordinances and statutes of the City of Birmingham

and State of Alabama; that the said conduct, actions

and conspiracies of the said respondents in the City

of Birmingham is such conduct as is calculated to

provoke breaches of the peace in the City of Birming

ham; that such conduct, conspiracies and actions of

said respondents as aforesaid threatens the safety

(fol. 71), peace and tranquility of the City of Bir

mingham” (R. 31, 32).

Such paragraph 3 continues with allegations that such

conspiracies and actions have already caused or resulted

in serious breaches of the peace and respondents threaten

to continue such unlawful conduct unless respondents are

enjoined2 (R. 31, 32).

2 “Such conduct, conspiracies and actions aforesaid have al

ready caused or resulted in serious breaches of the peace and

Paragraph 4 and its subsections outline specific in

stances of unlawful conduct. Some of these incidents

relate to trespass upon private property,3 parading with

out a permit on April 6th, 8th and 10th (R. 33). Sub

section (c) does not charge parading without a permit

but alleges that on April 7th, 1963, respondents organized

a parade or procession to march upon the City Hall and

incident thereto,

“ did further foster, encourage and cause a mob con

sisting of approximately 700 to 1,000 Negroes to con

gregate upon the public streets of the City of Bir

mingham, blocking and interfering with traffic, such

mob having been gathered to encourage the said

intended march on City Hall of the City of Birming

ham from a point several blocks from said City Hall,

which said mob became unruly, a number of such

mob blocked the sidewalks of the City of Birmingham

and a large number refused to obey the lawful orders

of officers of the Police Department of the City of

Birmingham in their efforts to disperse said unruly

mob” (R. 33, 34).

It is also alleged that the great throng caused to be con

gregated around the City Hall in connection with such

— 8 —

violations of and disregard and contempt for the law in nu

merous specific instances hereinafter set forth and complainant

avers that said respondents, separately and severally, threaten

to continue to sponsor, foment, encourage, incite, to he com

mitted or to commit further breaches of the peace and acts and

conduct which are in violation of and disregard for the law

unless respondents are enjoined therefrom” (R. p. 32).

3 This bill of complaint was filed and the injunction issued

and contempt charges heard and the petitioners convicted on

April 26, 1963. Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374, 83 Sup. Ct.

1311 (May 20, 1963) and similar cases from other states were

decided after the contempt conviction. Peterson v. City of

Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, 83 Sup. Ct. 1119 (May 20, 1963) ;

Avent v. North Carolina, 373 U. S. 375, 83 S. Ct. 1311 (May 20,

1963); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, 83 Sup. Ct. 1122.

— 9 —

proposed march required “ the blocking off of several

streets in the City of Birmingham to prevent breaches

of the peace and violence, including mob violence” (R.

34).

It is alleged in paragraph 5 that the acts alleged in the

two preceding paragraphs have placed an undue strain

upon the manpower of the Police Department of the City

of Birmingham in the effort to provide for the safety of

the respondents in said conduct and activities upon the

public streets and public places in said City and to pro

vide for the safety and tranquility of the entire citizen

ship and will cause damage to city property and injury

or loss of life to police officers (R. 34).

In paragraphs six and seven, a conspiracy of respond

ents and others to continue such actions and conduct to

the imminent danger to lives, safety, peace and tranquility

of the people of Birmingham unless enjoined is alleged4

(R. 34, 35). A threat to conduct “ Kneel-Ins” is alleged

in paragraph 8 (R. 35). In said paragraph 8, it is alleged

upon information and belief that the acts and conduct

4 Said paragraphs read as follows:

“ 6. Your complainant is informed and believes and upon such

information and belief avers that respondents, separately and

severally, and others acting in concert with respondents, whose

exact names and entities are otherwise unknown to your com

plainant at this time will continue to enter into the City of

Birmingham conducting themselves as above described, which

will lead to further imminent danger to the lives, safety, peace,

tranquility and general welfare of the people of the City of

Birmingham, Jefferson County, and the State of Alabama, and

that tension will continue to mount as such activities are con

tinued.

7. Your complainant is informed and believes and upon such

information and belief avers that there is strong and convinc

ing reason to believe that respondents and others acting in con

cert with respondents, whose names are otherwise unknown to

your complainant, have and will continue to conspire to engage

in unlawful acts and conduct as aforesaid unless enjoined from

so doing” (R. 34, 35).

— 10 —

of respondents “ is a part of a massive effort by respond

ents and those allied or in sympathy with them to forcibly

integrate all business establishments, churches, and other

institutions of the City of Birmingham” (JR. 35).

Allegations of irreparable injury are contained in para

graph 95 (R. 35).

The prayer for injunction is to restrain the parties,

their agents and servants, followers and those in active

concert with them and persons having notice of said

order from continuing any acts hereinabove designated,

particularly: I, engaging in, sponsoring, inciting or en

couraging (1) mass street parades, processions or like

demonstrations without a permit; (2) trespasses after

warning upon private property; (3) congregating upon

the streets or public places into mobs, and (4) unlawfully

picketing business establishments or public buildings or

performing acts calculated to cause breaches of the peace;

or II, conspiring to engage in: (1) unlawful street parades;

(2) unlawful processions; (3) unlawful demonstrations;

(4) unlawful boycotts; (5) unlawful trespasses and un

lawful picketing or other like unlawful act or from vio

lating the ordinances of Birmingham and statutes of

Alabama; or III, from doing any acts designed to con

summate conspiracies to engage in said unlawful acts

of (1) parading, (2) demonstrating, (3) boycotting, (4)

trespassing, and (5) picketing, (6) or other unlawful acts;

or IV, from engaging in acts and conduct customarily

known as “ Kneel-Ins” in churches in violation of the

5 Said paragraph reads: “9. Complainant avers that its rem

edy by law is inadequate, that the continued and repeated acts

of respondents, as herein alleged, will cause incidents of vio

lence and blood- (fol. 74) shed; that complainant has no other

adequate remedy to prevent irreparable injury to persons and

property in the City of Birmingham, Jefferson County, and

verily believes that such will occur if such respondents con

tinue to so conduct themselves which they will do if not re

strained by this Court.”

— 11 —

wishes and desires of the members of said churches6

(R. 40).

The temporary injunction writ issued in language identi

cal with the prayer of the bill (R. 43-45).

B. The Petition, for Rule Nisi.

The criminal contempt action was initiated by a peti

tion for rule nisi duly served upon all the respondents.

Such petition contained allegations charging the defiance

of the injunction and intention to disobey issued by the

Circuit Court of Alabama both in and prior to the press

conference held during the day of April 11th and in other

statements at meetings of the respondent, Alabama

Christian Movement for Human Rights on April 11th,

12th and 13th by petitioners, Martin Luther King, Jr.,

Abernathy, Shuttlesworth, Walker, A. D. King (Para

graphs 6, 7, 8 and 9—R. 85-86).

It is alleged in paragraph 7 that respondents, Aber

nathy, Shuttlesworth and A. D. King announced at the

meeting on April 11th they would participate in an un

lawful march or procession on April 12th and would go

to jail and solicited volunteers to engage in it. One or

more of said respondents openly boasted the injunction

had been violated that day (R. 85-86).

It is averred that at the April 12th meeting volunteers

were solicited to engage in unlawful processions, parades

and other unlawful activities; that respondent, Wyatt Tee

Walker, solicited volunteers to go to jail and also about

a dozen or two volunteers to die for the cause (Par. 8—

R. 36).

At the meeting on Saturday night, April 13th, respond

ent Walker called for volunteers to engage in an unlawful

6 Division of the prayer for injunction into numbered parts

is supplied in this brief for purpose of convenience and did not

appear in the original bill.

procession, in violation of the injunction and to go to jail.

A call was also made for children, ages from the first

grade np. Also a call was made for volunteers to call all

other Negroes to assemble as many Negroes as possible

at the time of the procession or march on Easter Sunday,

April 14th (Par. 9, R. 86, 89).

Specific overt acts in consummation of the conspiracy

and in violation of the injunction are alleged in paragraph

10 and its subparts (R. 87, 88). Paragraph 10 (B) relates

to the April 12th march or procession in which Peti

tioners Martin Luther King, Jr., Abernathy and Shuttles-

worth were direct participants (R. 87).

Allegations setting forth the gathering of the violent

mob on Sunday, April 14th, as a part of said conspiracy

are contained in paragraph 10-D.7 Direct participants

were respondents, A. D. King, Jr., J. W. Hayes, John

Thomas Porter and T. L. Fisher. All but said Fisher

7 “D. On Easter Sunday afternoon, in response to the said

solicitations made at said meeting on Saturday night, April

13th, as hereinabove alleged and as a part of said conspiracy

and concert of action, an unruly mob of chanting, dancing, hop

ping Negroes consisting of several thousand assembled in and

around Thurgood C. M. E. Church at 11th Street and 7th Ave

nue, North. An unlawful procession consisting of several hun

dred Negroes formed at said church and proceeded to parade

or march upon the public sidewalks and streets of the City of

Birmingham without a permit, unlawfully and in violation of

City Ordinance and in violation of said injunction. Said un

ruly mob followed along side, behind and in front of said pro

cession and persons forming a part of said mob threw rocks,

brickbats or other dangerous objects at members of the Police

Department of the City of Birmingham engaged in arresting

said members of said procession. A motor vehicle of the Police

Department was struck by a rock or brickbat or other hard ob

ject and was seriously damaged. Mr. James Ware, a newspa

per photographer employed by Birmingham Post-Herald, was

struck and injured by a rock or other dangerous object. Other

persons, including police officers, were narrowly missed by said

rocks or other dangerous objects which were thrown on said

occasion. One (fol. 125) officer of the said Police Department

was injured by one of said paraders or marchers resisting ar

rest in the tense atmosphere created by said mob” (R. 88).

— 12 —

— 13

were parties respondent and had been served with said

injunction prior thereto. The latter is alleged to have

participated with knowledge (Par. 11, R. 89).

C. Evidence.

Recruitment to Die and to Go to Jail.

At every meeting on April 12th, 13th and 14th, people

willing to go to jail were recruited, but at the meeting on

April 11th, petitioner Wyatt Tee Walker said “ he was

looking for two dozen Negroes who are willing to die

for me!” This testimony was given by Mr. J. Walter

Johnson, Jr., a reporter for the Associated Press, who

attended all of the meetings, April 12th through April

14th (Pet. Br. 7) and was testifying from his notes made

at the meetings (R. 202, 203, cross. 204).

On the question of recruitment to go to jail, Petitioner

Abernathy was upset because A1 Hibler, the Negro blind

singer who led a march on Wednesday and Thursday and

was not arrested (R. 189). He said, “ That is discrimina

tion and we don’t like it.” In other words that Hibler

was discriminated against because he was not arrested

(R. 190).

Dr. King said Ralph Abernathy and he were to follow

Hibler on Thursday but because he was not arrested on

Wednesday “ they gave him another opportunity on

Thursday and they would wait until Good Friday” (R.

189, 190).

Also at this meeting note was taken of some who had

just gotten out of jail. They were introduced to the

meeting by Rev. Young (R. 201, 202).

Recruitment of Participants in Marches.

Volunteers were enlisted to participate in the marches

(J. Walter Johnson, Jr., R. 193; Elvin Stanton, R. 245;

14 —

Petitioner T. L. Fisher, R. 301; Petitioner J. W. Hayes,

R. 333, 334). Petitioner Wyatt Tee Walker made a call

at the meeting on April 12th for students of Birmingham,

Grade 1 through graduate school, to meet Saturday morn

ing, April 13th. He said: “ There is something we want

to do with the student population of Birmingham. They

can get a better education in five days in this jail than

five months in school” (R. 202). At the meeting on Sat

urday night, April 13th, a call was made for volunteers

who would call all the Negroes in the community and get

them out the next day, Sunday, April 14th (Rev. T. L.

Fisher, R. 301, 302).

Secrecy as to Destination of Marches.

No evidence was offered of any effort to get a permit

relating to any march, procession or demonstration

charged in the rule nisi petition. The Court made it clear

that evidence of any effort made to get a permit for any

incident charged in such petition as a violation would be

relevant (R. 286, top of page). No such evidence was

ever offered, although it does appear that the head of the

Alabama Christian Movement, Rev. F. L. Shuttlesworth,

had been informed as early as April 5th of the proper

way to make an application for such a permit (R. 285,

Statement of Counsel for City).

Not only was there a failure to apply for a permit but

there was a failure or refusal to furnish accurate informa

tion as to the time, route and destination. The information

picked up by the Police Department on these mat

ters was imprecise and inaccurate. Word had been re

ceived from some source, possibly the press (R. 165) that

the demonstrations on April 12th and April 14th would

either be on City Hall or City Jail (Inspector Haley, R.

146 as to the 12th; Lieutenant Painter as to the 14th, R.

215). Rev. N. H. Smith and Rev. J. W. Hayes, both of

whom were robed participants in the April 14th march,

— 15 —

testified they did not know where the march was scheduled

to go (R. 315, 316, 338). On the afternoon of April 14th,

Lieutenant Painter questioned petitioner Wyatt Tee

Walker as to whether the destination was City Hall or

City Jail or neither (R. 215). Some information appears

to have come from petitioner Walker relating to April

12th, but this related to a march which was supposed to

come at 12:00 Noon or 12:15 (R. 180).

No Distinction Between Marchers and

Accompanying Crowds.

A large crowd gathered at a church on 6th Avenue,

North, at 16th Street. The march led by petitioners,

Martin Luther King, Jr., Abernathy and Shuttlesworth,

came out of the church but the crowd outside joined with

them. Lieutenant Painter testified, “ As the group came

out of the church then the whole group of people who

had assembled along the sidewalk followed along behind

them and I think you could describe it as one procession”

(R. 207). This related to the march held on April 12th

after 2:45 P. M. (R. 149, 206, 207).

Concerning the April 14th incident, the same witness

testified that as the marchers came out of the church and

started walking at a rapid pace, “ almost simultaneously

as if with the same movement, or I will say simultane

ously, this large crowd that had gathered outside began

moving along with them . . . covering, basically all the

area of the street and sidewalk” (R. 215). When Nelson

Henry Smith, Jr., one of the defendants on trial, was

asked on cross-examination whether anyone on the out

side of the church joined the some five or six hundred as

they came out of the church, he testified: “ Well, every

body was just going walking in the same direction” (R.

315). Inspector Haley said that after the Easter Sunday

march started: “ They did block the street. That is be

tween 11th Street and 7th Avenue up to 5th Alley and

— 16 —

11th Street. The street was solid, and the sidewalks were

solid with marchers” (R. 155). He described it as a

solid mass, filling the streets and sidewalks (R. 156, 157).

Complainants Exhibits 3, 4, 5 and 6, referred to by the

Alabama Supreme Court in its opinion (R. 436, bottom

of page) graphically depict the scene as photographed

by Mr. James Ware, Newspaper Photographer. These

exhibits appear on pages 411-414 of the record. They

were identified, described and introduced (R. 359, 360).

Exhibit 3 was taken within a block and a half of the

church from whence it started, the church appearing in

the picture on the right is not the church of origin (R.

360). Exhibit 4 shows police officers in the foreground

and the marchers in the background.

Marchers and Crowd Were One and Under

a Single Command.

Lieutenant Painter testified that on April 12th peti

tioner Wyatt Tee Walker, speaking and signalling to the

crowd, told them to circle the block one time. This was

after the police officers encountered difficulty in getting

the crowd to scatter (R. 208, 209). As to the April 14th

incident, Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, upon being told that

by Painter the concern of law enforcement officers in be

ing informed of the time and destination of the march

“ was in the interest of controlling the crowds and law

enforcement” , to which “ he replied . . . ‘ If you control

yourself and the police as well as I control this crowd,

there won’t be any problem. I guarantee you I can con

trol these people’ ” (R. 215).

Police Succeeded in Avoiding a

Serious Racial Conflict.

On both instances the police officers blocked the imme

diate area where the crowds were congregating both to

white pedestrians and vehicular traffic as a necessary pre

17 —

caution to prevent a conflict with white racial agitators

and because of the traffic hazard created (R. 154, 170,

174). Prom the experience of the “ Freedom Rider” in

cident when outside agitators assaulted and beat the

demonstrators, Inspector Haley was of the opinion that

the demonstrations then in progress were likely to attract

these trouble makers from out of Jefferson County with

a serious racial conflict resulting (R. 174). Inspector

Haley testified that these precautions succeeded in keep

ing down an undue amount of violence and strife and

trouble away from the City, and prevented racial con

flict between Negroes and whites (R. 185). To this ex

tent by hard effort, the Police Department had maintained

law and order (R. 182, 184) and had succeeded in their

purpose to protect the demonstrators (R. 161). This was

made more difficult by the refusal of the leaders to furnish

accurate information to the Police Department (R. 170).

Movement Psychology of Violence.

On cross-examination, Lieutenant Willie B. Painter tes

tified as to the nonviolent methods of the two organiza

tions involved. “ The teachings have been nonviolent.

The psychology and methods used have been to incite

others to create violence upon the participants in demon

strations” . He also said, “ There has been a complete

program within the last year or eighteen months of teach

ing hatred of the white people, that they are your ene

mies. They were teaching nonviolence on the one hand,

but on the other hand they were saying that the Negroes

in Birmingham, Alabama, are buying fire arms to pro

tect themselves. They were supposedly teaching non

violence but yet psychologically they were advocating

violence” (R. 220).

At the time of the defiant news release on the morning

of April 11th, Petitioner Shuttlesworth also used a sep

arate paper and made some comments in which he said:

— 18

“ If the police couldn’t handle it, the mob would” (R.

250).

Also in talking to Lieutenant Painter, Petitioner Walker

said if the Movement “ did not obtain the things that we

are seeking, then we will follow the course of revolution

to obtain these things” 8 (R. 213).

The Crowds Assembled Became Unruly,

Belligerent and Violent.

Inspector Haley was asked whether the crowds on both

occasions became unruly, to which he replied: “ Yes, and

belligerent. We did not make as many arrests as we

could have if we had just faced the crowd, hut we had

other work to perform” (R. 172). Inspector Haley also

testified: “ There was violence in that one or more officers

and a newspaper man had been injured and City property

destroyed, during these incidents” (R. 182). Other evi

dence of violence, especially on the occasion of April 14th

is detailed by the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 436).

That court made specific reference to the testimony of

■witnesses Painter (R. 216) and Ware (R. 231-233). Its

opinion also referred to the testimony of Painter that

petitioner Wyatt Tee Walker had formed the crowd out

side into a group that joined the April 14th march (R.

214, 215).

D. Treatment by Lower Courts.

The Circuit Court made clear at the outset before the

hearing began the issue he considered presented by the

contempt citation on the question of jurisdiction was

whether the court was an equity court and issued the

injunction in a case in which the Court had jurisdiction

over the parties. There remained only the question of

' This statement was in a contest of a discussion to the ef

fect that 2cc of the people in Russia succeeded in overthrow

ing the government R. 212. 213).

— 19 —

their having violated the injunction knowingly; that some

motion should have been filed so that the court could de

termine whether or not it had properly issued the in

junction before it was violated (E. 140).

In its opinion this court clearly limited the convictions

to criminal contempt for past conduct (E. 420). The

Court also commented on the absence of any evidence that

any effort had been made to comply with the require

ments of the permit ordinance. In its opinion the court

said:

“ The legal and orderly processes of the court

would require the defendants to attack the unreason

able denial of such permit by the Commission of the

City of Birmingham through means of a motion to

dissolve the injunction at which time this Court

would have the opportunity to pass upon the question

of whether or not a compliance with the ordinance

was attempted and whether or not an arbitrary and

capricious denial of such request was made by the

Commission of the City of Birmingham. Since this

course of conduct was not sought by the defendants,

the Court is of the opinion that the validity of its in

junction order stands upon its prima facie authority

to execute the same” (E. 422).

This court also concluded these petitioners were guilty

of a conspiracy, that is concerted efforts to personally

violate the injunction and encourage and incite others

to do so.0 9

9 The pertinent language of the court concerning all defend

ants except defendants Gardner, C. Woods, A. Woods, Jr. and

Palmer, as to whom motion to exclude the evidence was granted

is as follows: “Under all the evidence in the case, the Court is

convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the remaining defend

ants had actual notice of the existence of the prohibitions, as

contained in the injunction, and of the existence of the order

itself; and that the actions of all the remaining defendants

were, in the opinion of this Court, obvious acts of contempt,

constituting deliberate and blatant denials of the authority of

— 20 —

This Court also relied upon and cited United States v.

United Mine Workers of America, 330 U. S. 308 (concur

ring opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter).

The Alabama Supreme Court, in reliance upon the same

Mine Workers case (330 U. S. 258, 290-295), and Howat v.

Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, and citing the concurring opinion

of Mr. Justice Harlan in In Re Green, 369 U. S. 689, 693

(R. 440-442) decided the case as one in criminal contempt

only and upon the proposition that it is the duty of one to

obey an injunction, even if it should be based upon en

forcement of an invalid ordinance, until he takes appro

priate legal steps to accomplish its discharge or dis

solution.

The Alabama Supreme Court determined the jurisdic

tional right of the Circuit Court to issue injunctions un

der Sec. 144, Constitution of Alabama, and Secs. 1038 and

1039, Code of Alabama, 1940 (R. 439), but did not explore

the constitutionality of Sec. 1159. It found there were no

procedural defects in the proceeding, except as to three

respondents, as to whom the Court felt there was insuf

ficient evidence to show a violation of the injunction with

notice of its terms” 10 (R. 446, 447).

this Court and its order and were concerted efforts to both

personally violate the said injunctive order and to use the per

suasive efforts of their positions as ministers to encourage and

incite others to do likewise” (R. 422).

10 The three as to whom convictions were quashed were

Andrew Young, James Bevil, and N. H. Smith, Jr.

— 21 —

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

I.

The Supreme Court of Alabama, in the opinion under

review, had on certiorari reviewed the decision of the

Circuit Court from the criminal contempt convictions on a

record which that Court concluded shows wilful contempt

on the part of petitioners after service upon them of the

bill of complaint and writ of injunction, with the excep

tion of petitioners Hayes and Fisher, both of whom were

parties but had not been served but as to whom the Court

concluded they violated the injunction with notice. It is

submitted that court properly held the issue of the con

stitutionality of Ordinance 1159, Parading Without a

Permit, was not presented for review on certiorari from

the Circuit Court which had jurisdiction to issue the in

junction because it was a court of equity, had jurisdiction

of the parties and no effort was made to modify or dis

solve such injunction prior to its violation, there

being no question of procedural defects in the contempt

proceedings, no contention appearing in the record that

after the injunction was issued any effort was made to

request a permit or otherwise attempt to comply with the

injunction insofar as it banned parading without a per

mit as required by such ordinance. Such conclusion of

the Alabama Supreme Court rested on an adequate state

ground, that is, that on certiorari from a criminal con

tempt conviction in such case the Court will not consider

the merits of the injunction, even if it rested upon an

ordinance or statute found to be unconstitutional, a doc

trine accepted by state and federal courts alike. Howat

v. Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, 42 S. Ct. 277; United States v.

United Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258; In Re Green, con

curring opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan, 369' U. S. 689, 693;

Ex Parte Hacker, 250 Ala. 64, 33 So. 2d 324; Hotel and

Restaurant Employees, etc. v. Greenwood, 249 Ala. 265,

30 So. 2d 696, Cert. Den. 322 U. S. 847, 68 S. Ct. 349.

22 —

A. The Alabama Circuit Court at least had jurisdiction

to determine its own jurisdiction and wilful violation of

its injunctive decree is punishable as criminal contempt

even if the court ultimately is determined to have no

jurisdiction. Shipp v. United States, 1906, 203 U. S. 563,

27 S. Ct. 165, 51 L. Ed. 319, 8 Ann. Cas. 265; Howat v.

Kansas, 1922, 258 U. S. 181, 42 S. Ct. 277, 66 L. Ed. 550;

Carter v. United States, 1943, 5th Cir., 135 Fed. 2d 858;

In re Williams, 26 Pa. 9, 67 Am. Dec. 374; Sima Piano

Company v. Fairfield, 103 Wash. 206, 174 Pac. 457.

Reid v. Independent Union A. W., 200 Minn. 599, 271

N. W. 300, 120 APR. 297; Main Cleaners & Dyers v. Colum

bia Super Cleaners, 332 Pa. 71, 2 A. 2d 700; See also Stoll

v. Gottlieb, 305 U. S. 165, 171, 172, 59 Sup. Ct. 134, 83

L. Ed. 104, 108, 109; 38 Am. Banks, U. S. 79; cf.—Jones

v. Securities and Exchange Comm., 298 U. S. 1, 56 Sup. Ct.

654, 80 L. Ed. 1015, 1021, 1022.

The orderly and legal way to have tested the Alabama

Circuit Court temporary injunction was to file a motion

to dissolve which could have raised the question of the

court’s authority and all constitutional or other questions

relating to the temporary injunction as petitioners knew

and mentioned in their news release, an appeal from a

ruling on which motion lies to the Supreme Court as a

preferred case. Alabama Supreme Court Rule 47 (Appen

dix, pages 76-77). The principal petitioners knew and

mentioned on the day they received service of the injunc

tion the proper way to attack it was to move its dissolu

tion. They also said they would violate the injunction

regardless and made no effort to comply and stated they

would do so and risk the possible consequences involved.

B. The rule applies even if constitutional freedoms are

involved in complying with the injunction, since the Court

will not consider the merits of the main case in the col

lateral matter of contempt, as the motion to dissolve the

injunction in a direct proceeding is the only remedy un

less the issuing court is totally without jurisdiction to

issue the injunction. Howat v. Kansas, 258 U. S>. 181, 42

Sup. Ct. 277; Schwartz v. United States, 1914 (C. C. A. 4),

217 Fed. Rep. 866; Allen v. United States, 1922 (C. C. A.

7), 278 Fed. 429; Clarke v. Fed. Trades Comm., 128 Fed.

2d 542; United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S.

258, supra; Ex parte Hacker, 250 Ala. 64, 33 So. 2d 324;

Hotel and Restaurant Employees, etc. v. Greenwood, 249

Ala. 265, 30 So. 2d 696, cert. den. 322 U. S. 847, 68 S. Ct.

349; cf. United States v. Debs, C. C. 111., 64 Fed. 724, error

denied, In Re Debs, 159 U. S. 251, 15 S. Ct. 1039; cf. In

Re; Debs, 158 II. S, 564, 15 S. Ct. 900.

C. Any argument, regardless of how plausible and al

luring it may sound, which has at its underlying roots the

doctrine that any citizen is entitled to wilfully violate an

injunction issued against him without making any effort

to comply with it, or as to that matter wilfully violate

any law applicable to him simply because he does not feel

it is just as to him, without having recourse to remedies

duly provided by the law is untenable because the ultimate

and inexorable end result is chaos and anarchy. Gompers

v. Bucks Stove & Range Co., 1911, 221 U. S. 418, 450, 31

Sup. Ct. 492, 501, 55 L. Ed. 797, 34 L. R. A. (U. S.) 874;

United States v. United Mine Workers of America, 1947

(Mr. Justice Frankfurter concurring), 330 U. S. 258, 307,

308, 309, 67 Sup. Ct. 677, 703; Cox v. State of Louisiana,

1965, 379 U. S. 536, 554, 85 S. Ct. 453, 464, dissenting

opinion of Mr. Justice Black, 379 U. S. at pages 583, 584.

The record in this case compels the conclusion that peti

tioners in this case, and especially those who openly de

clared their intentions to violate the injunction had the

uttermost contempt for the court and the injunction and

made no effort whatever to comply with it but to the

contrary exploited its intentional violation as a vehicle

to obtain nationwide publicity in press, radio and TV.

— 23 —

— 24

In Re: Debs, 1895, 158 U. S. 564, 15 S, Ct. 900; United

States v. Barnett, 1964, 376 U. S, 681, 697, 84 S. Ct. 984,

993.

Submission under this Section I is that the contempt

convictions of petitioners should be sustained as against

the several constitutional grounds asserted in opposing

briefs, treating the convictions as having been solely based

upon a violation of ordinance 1159, without considering

the constitutionality thereof because of the failure of peti

tioners to present such constitutional contentions by mo

tion to dissolve prior to wilfully violating the injunction.

It is assumed arguendo that no enjoinable conduct other

than simply failure to obtain a parade permit is involved.

The primary basis is the rule of Mine Workers and

Howat v. Kansas, which we urge be left unchanged.

II.

The criminal contempt convictions of petitioners are

not erroneous and subject to reversal on account of the

contentions made in briefs for petitioners and the United

States, as amicus curiae that there was lack of due process

or failure to afford equal protection of the laws or a

violation of the freedom of speech or assembly provisions

of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

A. Aside from any consideration of ordinance 1159, as

a support for the injunction, the conduct of petitioners

shown by the record discloses a conspiracy to violate the

injunction in the news conference, repeated meetings of

the “movement” resulting in the march on April 12th and

culminating in the assembly of the mob and the march or

procession of April 14th, when correct information as to

time, route and destination were not only not furnished

police authorities, but such information wilfully with

held, and where the entire street and both sidewalks were

preempted and commandeered by the procession or march-

— 25

ers and whose destination whether to City Hall, Northeast

or City Jail, Southwest of the starting place, was

shrouded in secrecy and which formed an unruly, bellig

erent, howling, cursing mob, gathered by and controlled

by petitioners and those in concert of action with them,

is conduct which cannot under any circumstances qualify

as constitutionally protected.

B. The First and Fourteenth Amendments do not con

fer absolute right to patrol, march, picket or otherwise

use the streets as means of communicating ideas. Such

rights are subject to the concommitant right and duty of

the City to control the use of the streets for the common

use and welfare of the public. Cox v. Louisiana, 1965, 379

U. S. 536, 554, 558, 85 S. Ct. 453, 464, 468. The existence

of the injunction in part rested upon ordinance 1159,

which assuming arguendo to be unconstitutional and that

such part of said injunction is therefore void, do not con

fer any rights upon petitioners to engage in nonconstitu

tionality protected acts described in A, above, and which

are otherwise validly prohibited by the injunction. Liquor

Control Commisison v. McGillis, 1937, 91 Utah 586, 65

Pan. 2d 1136; Kaner v. Clark, 108 111. A. 287; Ex P. Tins

ley, 37 Tex. Cr. 517, 40 S. W. 306; In Re Landau, 243

N. Y. S. 732, 230 App. Div. 308, app. dismissed 255 N. Y.

567, 175 N. E. 316.

C. The clear scope and central purpose of the verified

bill for the injunction was to preserve law and order in a

situation alleged to involve imminent danger of lawless

ness, violence, bloodshed and serious loss and damage to

property of the city and others and mass violations of

city and state laws, especially alleging interference in the

use of the streets by the congregating of a large unruly

mob with threatened breaches of the peace and mob vio

lence in consummation of a conspiracy and threatened con

tinuation of such conduct unless enjoined. All of which

constituted an enjoinable public nuisance without regard

— 26 —

to Ordinance 1159. In Re Debs, 158 U. S. 564, 15 S. Ct.

900; 39 L. Ed. 1092; City of New Orleans v. Liberty Shop,

1924, 157 La. . . . , 101 So. 797; General City Code of Bir

mingham, 1944, Sec, 311; Code of Alabama 1940 (1958

Rec. Ed.), Sections 505, 506; cf. United States v. U. S.

Klans, Knights of Ku Klux Klan, Inc., 1961, 194 Fed.

Supp. 897; U. S. v. Parton, 1943 (C. C. A. 4), 132 Fed.

2d 886, 887; Cox v. Louisiana (Mr. Justice Black, dissent

ing), 1965, 379 U. S. 578, 85 S. Ct. 453, 468, 471.

The contempt convictions may be properly rested upon

violation of those parts of the injunction writ prohibiting

the congregation of mobs upon public streets and public

places, and in connection therewith conduct calculated to

cause a breach of the peace and violation of city and

state laws, especially those related to the use of streets

and sidewalks and such injunction writ is not void for

vagueness or overbreadth. In Re Debs, 1895, 158 U. S.

564, 15 S. Ct. 900; Congress of Racial Equality v. Clem

mons, 1963 (C. C. A. 5), 323 Fed. 2d 54, 58, 64 (Gewin,

Circuit Judge, concurring); Griffin v. Congress of Racial

Equality, 1963, 221 Fed. Supp. 899; cf. United States v.

United Klans, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc., 1961,

194 Fed. Supp. 897; cf. Kelly v. Page, 1964 (C. C. A. 5),

335 Fed. 2d 114.

D. No lack of due process is involved for lack of evi

dence to show the violation of such parts of such injunc

tion. Poliafico v. United States, 237 Fed. 2d 97, 104 (C. A.

6, 1956); cert. den. 352 U. S. 1025, 77 S. Ct. 590, 1 L. Ed.

2d 597; Blumenthal v. United States, 332 U. S., pages 539,

559, 68 Sup. Ct. 248, 257; United States v. Rosenberg

(C. C. A. 2, 1952), 195 Fed. 2d 583, 600, 601, cert, denied,

344 U. S. 838, 73 S. Ct. 20, 21, 97 L. Ed. 652, reh. denied,

344 U. S. 889, 73 S. Ct. 134, 180, 97 L. Ed. 687, reh. denied

347 U. S. 1021, 74 S. Ct. 860, 98 L. Ed. 1142, motion de

nied 355 U. S. 860, 78 S. Ct. 91, L. Ed. 2d 67; In Re Debs,

1895, 158 U. S. 564, 15 S. Ct. 900.

— 27 —

III.

Considering matters presented in I and II, we submit

the constitutionality of Ordinance 1159 is not an issue

which is appropriately required to be determined in this

case, especially in view of the fact that its constitutional

ity has not been passed upon by the Supreme Court of

Alabama which granted certiorari and has under review

the decision of the Alabama Court of Appeals rendered

on such ordinance in Shiuttlesworth. v. City, 43 Ala. App.

68, 180 So. 2d 114 (Petitioners brief, page 10, Footnote 7).

IV.

The trial court and the Alabama Supreme Court con

sidered the defiant news releases and statements in their

relationship to the conspiracy to violate the injunction,

and as evidence of intent to wilfully violate without first

moving to dissolve it. In its context of apparent intent to

intimidate and exert pressure on the trial court, it was the

feeling of counsel for the City that such acts constituted

a basis to support the conviction of those involved but the

Alabama Courts refused to so deal with the news release

and related statements.

The convictions of petitioners were for a conspiracy to

violate the injunction, it is therefore not necessary to the

validity of such convictions that each petitioner is proven

to have participated in each stage or every overt act in

its consummation where the evidence discloses he was a

participant in and a part of the over-all conspiracy.

Each conspirator is guilty in equal degree for “all that

may be or has been done” whether he entered the con

spiracy at the beginning or later. Poliafico v. United

States, 237 Fed. 2d 97, 104 (C. C. A. 6, 1956); cert. den.

352 IT. S. 1025, 77 S. Ct. 590, 1 L. Ed. 2d 597; Blumenthal

v. United States, 332 U. S., pages 539, 559, 68 Sup. Ct.

248, 257; United States v. Rosenberg (C. C. A. 2, 1952),

195 Fed. 2d 583, 600, 601, cert, denied 344 U. S. 838, 73

S. Ct. 20, 21, 97 L. Ed. 652, reh. denied, 344 U. S. 889, 73

S. Ct. 134, 180, 97 L. Ed. 687, reh. denied 347 U. S. 1021,

74 S. Ct. 860, 98 L. Ed. 1142, motion denied 355 U. S. 860,

78 S. Ct. 91, L. Ed. 2d 67; In Re Debs, 1895, 158 U. S. 564,

15 S. Ct. 900.

The penalty assessed showed no distinction between

the principals who made the defiant statements and gave

out the defiant news releases and those who had lesser

facts in the conspiracy to violate the injunction.

Certainly these petitioners were deprived of no con

stitutional rights to influence the reversal of the Alabama

Supreme Court in connection with such verbal acts in

consummation of the conspiracy.

y.

The evidence in the record is adequate to sustain the

convictions of petitioners Fisher and Hayes, both of whom

are members of A. C. M. H. R., a party to the injunction

suit, and although they had not been served with the writ

knew of it prior to its violation. The evidence and infer

ences to be drawn therefrom leads to a conclusion they

had notice or knowledge of what acts it prohibited, as the

Alabama Supreme Court found. The doctrines of Thomp

son v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 80 S. Ct. 624, 4 L. Ed. 2d

654; Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248, only apply

when there is complete lack of evidence from which an

inference could be drawn to support the convictions. On

certiorari the ordinary practice of this Honorable Court

is not to review the weight or sufficiency of the evidence.

Whitney v. California, 274 TJ. S. 397, 47 S. Ct. 641, 71 L.

Ed. 594; Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor

Dairies, 312 H. S. 287, 61 S, Ct. 552, 85 L. Ed. 836; Port

land R. L. and P. Co. v. Railroad Commission, 229 U. S.

397, 33 S. Ct. 829, 57 L. Ed. 1248.

— 28 —

— 29 —

ARGUMENT.

I.

The Convictions Should Be Affirmed on the Rule of

HOWAT v. KANSAS and MINE WORKERS With

out Reaching Constitutional Issues Concerning Ordi

nance 1159.

The Supreme Court of Alabama did not enter into con

sideration of the alleged invalidity of Sec. 1159 of the

City Code of Birmingham. The case was decided on what

we believe is an adequate state ground. The injunction

order, issued by a circuit judge in equity, who was

clothed with constitutional and statutory jurisdiction11

to issue an injunction in a case arising with respect to

matters and parties physically within its jurisdiction.

In Howat v. Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, 42 S. Ct. 277, relied

upon by the Alabama Supreme Court, the United States

Supreme Court in a unanimous opinion written by Mr.

Chief Justice Taft in Case No. 491, one of the two cases

11 Both are quoted in the Alabama Supreme Court Opinion

(R. 439) and are as follows: “See. 144. A circuit court, or a

court having the jurisdiction of the circuit court, shall be held

in each county in the state at least twice in every year, and

judges of the several courts mentioned in this section may hold

court for each other when they deem it expedient, and shall do

so when directed by law. The judges of the several courts men

tioned in this section shall have power to issue writs of injunc

tion, returnable to the courts of chancery, or courts having the

jurisdiction of courts of chancery.”

“ §. 1038. Injunctions may be granted, returnable into any of

the circuit courts in this state, by the judges of the supreme

court, court of appeals, and circuit courts, and judges of courts

of like jurisdiction.”

“ § 1039. Registers in circuit court may issue an injunction,

when it has been granted by any of the judges of the appellate

or circuit courts when authorized to grant injunctions, upon the

fiat or direction of the judge granting the same indorsed upon

the bill of complaint and signed by such judge.”

— 30

decided, review of a contempt conviction in the courts of

Kansas was sought. The injunction issued to enjoin a

strike in the mining industry. Petitioners alleged the

Industrial Court Act of Kansas “ was void because in

violation of the federal constitution and the rights of de

fendants thereunder, and so the court was without power

to issue an injunction as prayed.” 258 U. S. at pages 187-

188. The position of the Kansas Supreme Court was that

the defendants were precluded from such attack in a col

lateral contempt proceeding.

The U. S. Supreme Court agreed (258 U. S., at pages

189-190):

“ An injunction duly issuing out of a court of gen

eral jurisdiction with equity powers, upon pleading

properly invoking its action, and served upon persons

made parties therein, and within the jurisdiction,

must be obeyed by them, however erroneous the ac

tion of the Court may be, even if the error be in the

assumption of the validity of a seeming but void law

going to the merits of the case. It is for the court of

first instance to determine the question of the va

lidity of the law, and until its decision is reversed

for errors by orderly review, either by itself or by a

higher court, its orders based on its decision

are to be respected, and disobedience of its law

ful authority to be punished. Gompers v. Bucks

Stove & Range Co., 221 U. S. 418, 450, 31 Sup. Ct.

416, 55 L. Ed. 797, 34 L. R. A. (U. S.) 874; Toy Toy

v. Hopkins, 212 U. S. 542, 541, 29 Sup. Ct. 416, 53

L. Ed. 644. See also United States v. Shipp, 203 U. S.

563, 27 Sup. Ct. 165, 51 L. Ed. 319, 8 Ann. Cas. 265

As the matter was disposed of in the State Courts

on principles of general, and not federal law, we have

no choice but to dismiss the writ of error as in No.

154.”

— 31 —

Mr. Chief Justice Vinson, in United States v. United

Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258, 67 8. Ct. 677, quotes with

favor the first paragraph above quoted from Howat v.

Kansas, concerning the duty to obey an injunction though

it may be based upon an unconstitutional or void law,

and concludes:

“ Violations of an order are punishable as criminal

contempt even though the order is set aside on ap

peal, Warden v. Searls, 121 U. S. 14, (1887), or

though the basic action has become moot, Gtompers v.

Buck Stove & Range Co., 221 U. 8. 418 (1911).” (330

U. 8. 258, 293, 294.)

The Alabama Supreme Court also relied upon the

United Mine Workers case and quoted at length from it

(R. 440-444). It also cited the concurring opinion of Mr.

Justice Harlan in In Re Green, 369 U. S. 689, 693 (R. 444).

In Re Green is cited and relied upon by petitioners un

der Sections I and II of their brief in substantial effect

that this case in some way weakens the application of

Howat v. Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, and United Mine Work

ers. We do not feel Re Green in any way conflicts with

the result reached by the Alabama Supreme Court in ap

plying the doctrine of Howat v. Kansas and United Mine

Workers to the instant case.

In Green, a member of the bar was sentenced to jail

and fined for contempt. When advised by the clerk an

injunction had been requested, he expressed his desire for

a hearing for which he was ready at any time. The in

junction was nevertheless issued ex parte. He then im

mediately asked for a hearing; but none was granted. At

the time the ex parte injunction was granted, the union

had on file with the National Labor Relations Board a

charge of an unfair labor practice concerning the same

controversy, but no hearing had been held on it.

32 —

Petitioner believed under Ohio law the injunction was

invalid because issued without a hearing and also because

the controversy was one for the National Labor Relations

Board and not for the state court. He therefore advised

the union officials the injunction was invalid and the best

way to contest it was to continue the picketing and to ap

peal or test any order of commitment for contempt by

habeas corpus. Gfreen was held in contempt for giving this

advice and although he was not allowed to testify in his

defense at the contempt hearing he offered to testify that,

“ I was convinced that both the judge and Mr. Ragan (op

posing counsel) were aware that I had consented to bring

these men before the court and stipulate the essential mat

ters for the express purpose of testing the validity of the

court’s order and its jurisdiction over the subject matter.’ ’

The majority opinion of this Honorable Court com

mented upon the conviction without a hearing and the

evils thereof, but also did refer to Mine Workers, and dis

tinguish it on the authority of Amalgamated Association

of St. Elec. Ry. & Motor Coach, etc. v. Wisconsin Employ

ment Relations Board, 340 U. S. 383, 71 S. Ct. 359, 95 L.