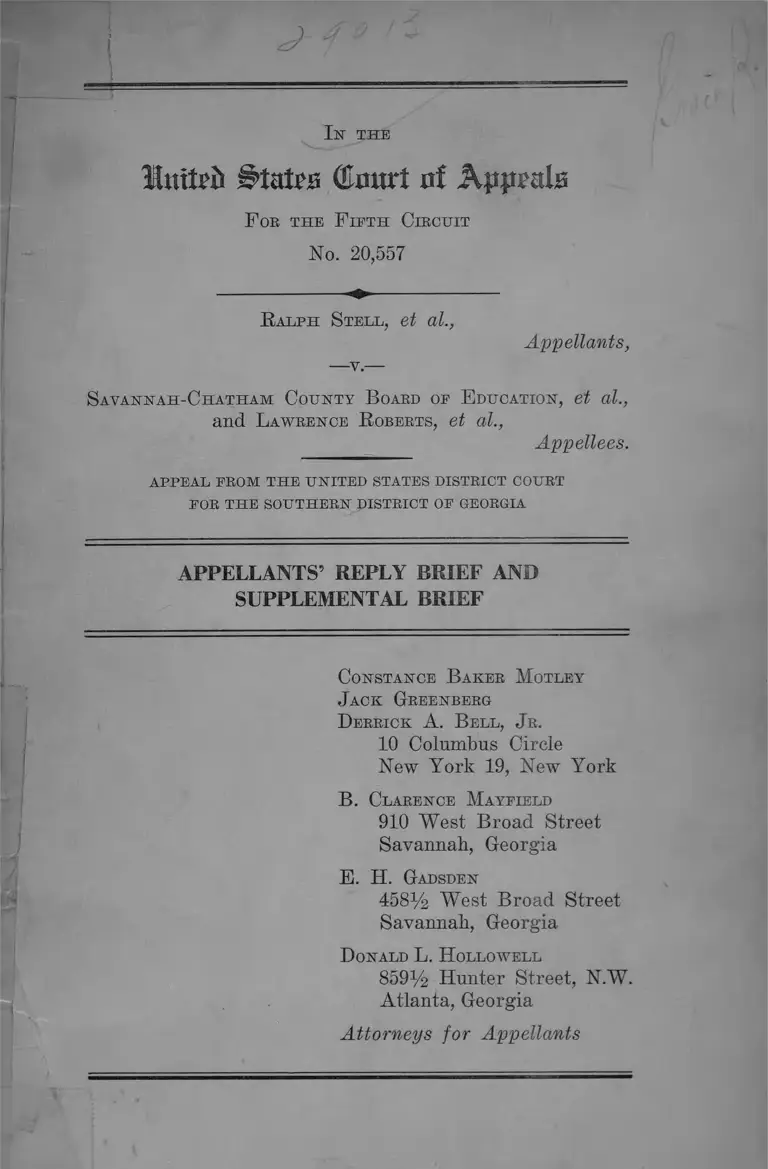

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Appellants' Reply Brief and Supplemental Brief

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Appellants' Reply Brief and Supplemental Brief, 1964. 53a5401d-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/907649c7-3dac-4d7d-a814-8e879287c842/stell-v-savannah-chatham-county-board-of-education-appellants-reply-brief-and-supplemental-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1st the

States ©curt o! Appeals

F oe th e F if t h C ibcitit

No. 20,557

R a l p h S te ll , et al.,

Appellants,

—v.-

S a v a n n a h -C h a t h a m C o u n ty B oard of E ducation , et al.,

an d L aw rence R oberts, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TH E SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF AND

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

C onstance B ak er M otley

J ac k Greenberg

D errick A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

B. Clarence M ayfield

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

E. H . Gadsden

458% West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

D onald L. H ollow ell

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement ........................................................................... 1

A r g u m e n t

I. The Appeal Is Not Moot .................................... 5

II. The Desegregation Plan Is Constitutionally In

adequate .................................................................. 10

C o n clu sion .......................................................................................... 13

T able of C ases

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) ......................... 11

Bates v. Batte, 187 F. 2d 142 (5th Cir. 1951) --------- ------ 9

Blanchard v. Commonwealth Oil Co., 294 F. 2d 834

(5th Cir. 1961) ........................................................- .... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1959) .... 10

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) ................................................................ 11

Carter v. Campbell, 285 F. 2d 68 (5th Cir. 1960).......... 9

Dempsey v. Guaranty Trust Co., 131 F. 2d 103 (2d Cir.

1942), cert, denied 318 U. S. 769 ................................. 8

Goss y. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 ..................................... ..................... ........ 10

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, 321 F.

2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................................... 10

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962).............................. 11

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ...................... 10

Isr the

IniUb (Cnnri nf Appeals

F oe th e F if t h C ibcu it

No. 20,557

R a l p h S te ll , et al.,

— v.-

Appellcmts,

S a v a n n a h -C fiath am C o u n ty B oakd of E d ucatio n , et al.,

and L aw ren ce R oberts, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM T H E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF AND

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

Statement

This brief serves a dual function. It is submitted, first,

as a reply to the contention of the defendant-appellee Board

of Education that the appeal is moot. Second, it discusses

the proceedings in the district court following this Court’s

order of May 24, 1963 directing the district court to grant

an injunction pending appeal. A supplemental record of

those proceedings has been filed.

Facts Relevant to the Question of Mootness

On May 13, 1963, the district court issued its Order and

Decree (R. 235) accompanied by “Preliminary Findings

and Conclusions” (R. 225). The order declared that “ the

injunction prayed for by the plaintiffs in this case is de

2

nied,” provided for possible testing of students in the

school system, and denied costs to any party (R. 235). The

preliminary nature of the findings and conclusions was

explained by the district court as follows:

In response to plaintiffs’ further request for an early

ruling herein the following findings of fact and con

clusions of law under Rule 52 of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure are made on a preliminary basis. The

Court will issue its formal opinion and final findings

within the next thirty days (R. 226).

On May 15, 1963 plaintiffs filed notice of appeal from

the order of May 13 (R. 236). This Court assumed juris

diction and on May 24, 1963 ordered the granting of an

injunction pending appeal. The proceedings held in the

district court pursuant to that order are described in the

second section of this statement.

On June 11, 1963, the district court notified all parties

that the “ formal opinion and final findings” would be pre

pared by June 28 (R. 254). On June 19, plaintiffs included

in their designation of the contents of record on appeal the

following entry: “ 7. Formal Opinion and Final Findings—

(to be entered)” (R. 255).

On June 28, 1963 the district court issued its “ Opinion

and Judgment.” Pursuant to the plaintiffs’ designation,

this was included in, and printed in, the record that is

now before this Court (R. 260). The portion of the docu

ment labeled “Judgment” declares, “ The injunction prayed

for by the plaintiffs in this case is denied and the complaint

is dismissed” (R. 301). In addition, it denies costs to any

party, makes provision for a possible showing of inequality

in specialized instruction, provides for possible testing of

students, and stipulates that “ Orders heretofore entered

under mandate from the Court of Appeals with respect to

3

a preliminary injunction remain of force and effect pending

a prompt appeal from this decision on the merits” (E.

301-02).

No separate notice of appeal from the order of June 28

was filed by plaintiffs. It is noted, however, that far from

considering the case as settled, the plaintiffs, subsequent

to June 28, participated in a hearing on the defendants’

plan of desegregation, appealed from the district court’s

order of July 29, and continued to prosecute this appeal.

Proceedings Following the Injunction Pending Appeal

On May 24, 1963, this Court ordered the district court

to enter a judgment requiring the defendant Board of

Education to submit a plan of school desegregation by

July 1, 1963 to include the desegregation of one grade by

September 1963 (Supp. E. 3). This Court’s order con

cluded with the following:

This order shall remain in effect until the final deter

mination of the appeal of the within case in the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on the merits, and

until the further order of this Court. During the pen

dency of this order the trial court is further directed

to enter such other and further orders as may be ap

propriate or necessary in carrying out the expressed

terms of this order (Supp. E. 8).

On May 31, 1963, the district court adopted the above

order as its own (Supp. E, 9-15). On July 1, the defendant

Board submitted its desegregation plan (Supp. E. 18), and

plaintiffs filed their objections on July 10 (Supp. E. 28).

A hearing was held on the adequacy of the plan (Supp. E.

31-104). On July 29, 1963, the district court rendered its

judgment refusing to approve or disapprove the plan on

the ground that it lacked jurisdiction to do so (Supp. E.

4

104-116). Plaintiffs tiled notice of appeal on August 28

(Supp. E. 117). Despite the ruling of the district court,

the Board of Education has carried its plan into execution.

The desegregation plan submitted by the Board calls for

“desegregation” of the twelfth grade in September 1963 and

one grade per year thereafter in descending order (Supp.

E. 26). In “desegregated” grades, Negro (or white) stu

dents may apply for transfer to white (or Negro) schools.

Applications must be signed by both parents, notarized,

and submitted during a fifteen-day period in advance of

the school year (Supp. E. 22-23). The plan designates

seventeen criteria on which the Superintendent may base

his decision (Supp. E. 21-22). An appeal to the Board of

Education is provided for unsuccessful applicants (Supp.

E. 23-26).

The plan contemplates no deviation from total segrega

tion in the lower grades. Students entering the first grade

and students newly entering the school system will continue

to be assigned to segregated schools on the basis of race.

The procedures and criteria applicable to transfers in “de

segregated” grades do not apply to students in lower grades

who request transfer from one segregated school to another

segregated school (Supp. E. 72-73, 76).

Except for the complex transfer procedures established

in the plan, no effort will be made by the Board of Educa

tion to transform a segregated system into a desegregated

one. Dual zone lines will continue to be operative, even in

“ desegregated” grades (Supp. E. 77).

Apart from general statements concerning the size of

the school system, the complexities involved in operating

a school system, the amount of school construction now in

progress, and the demands on the time of Board members,

no reasons were given for the failure of the plan to provide

for more effective desegregation in a shorter period of time.

5

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Appeal Is Not Moot.

The defendant-appellee Board of Education contends in

its brief, page 4, that the appeal is moot because the district

court dismissed the case on June 28, 1963 and no appeal was

taken. The argument appears to say that questions relating

to the denial of a preliminary injunction, such as those

presented by this appeal, no longer require decision because

the dismissal below and failure to appeal irrevocably de

prive plaintiffs of ultimate relief. Such an argument ig

nores entirely the actualities of this litigation.

The present appeal is taken from the district court’s

order of May 13, 1963. It is not disputed, and it could not

be, that that order was appealable and was properly ap

pealed from. The Board of Education’s argument assumes

that the order of May 13 was no more than a denial of a

preliminary injunction and that the subsequent order of

June 28, 1963 was a separate adjudication finally disposing

of the merits. That assumption is not supported by the

record.

Plaintiffs-appellants submit that the order of June 28

has no independent significance. The order of May 13

decided all questions in the case at the district court level,

both those relating to the requested preliminary injunction

and those relating to the requested ultimate relief, a per

manent injunction. The order of June 28 was merely a

formalizing of the earlier order, or judgment. In the typi

cal case the denial of a preliminary injunction need not

foreclose all issues relating to the request for a permanent

injunction. Nonetheless, a review of the record in this case

6

discloses quite clearly that the order of May 13 disposed of

all issues in the case, and the appeal from that order

presents all issues to this Court on this appeal.

1) Plaintiffs requested both permanent (R. 4) and pre

liminary (R. 129) injunctive relief. The order of May 13

did not purport to deny only the preliminary injunction.

By its terms, it denied “ the injunction prayed for by the

plaintiffs in this case” (R. 235). Those words appear quite

plainly to cover both types of requested relief.

2) The order of June 28 provides: “ The injunction

prayed for by plaintiffs in this case is denied and the com

plaint is dismissed” (R. 301). The words in the first clause

are identical to those in the order of May 13. If the moot

ness argument of the defendants is to be accepted, the

phrase “ the injunction” meant preliminary injunction on

May 13 and permanent injunction on June 28.

3) The order of May 13 followed what the district court

considered to be a complete trial on the merits. It extended

over a period of three days. All parties were given the

opportunity to present extensive testimony.

Plaintiffs had requested a hearing on their motion for

preliminary injunction. This being an ordinary suit to

desegregate a public school system, and the essential facts

being undisputed, a hearing on the motion for preliminary

injunction should have been a relatively uncomplicated pro

ceeding. Having readily established the essential elements

of their case, and the Board of Education having closed its

case, the plaintiffs on May 9 sought an immediate ruling

(Tr. 85-86). The district court, however, denied the motion

(Tr. 88) and allowed the interveners to present their psy

chological evidence. In clarification, counsel for the inter

veners said, “ it is my understanding that this is a trial on

7

the merits, on this action, and not merely on the motion.”

The court replied, “Well, it looks like I am proceeding

on that theory of hearing it all” (Tr. 88). Throughout the

prolonged testimony of the interveners’ witnesses, the court

repeated its desire to hear it all (Tr. 97, 130-31, 137, 261).

4) Both the defendants (R. 213) and the defendant-

interveners (R. 18, 199) had answered the Complaint by

the time of trial.

5) The district court, realizing that a prompt appeal

was in the offing, issued an appealable order supported by

findings and conclusions at the end of the trial on May 13.

Expressing an intention to elaborate on the reasons for its

ruling the court said:

Plaintiffs requested early trial in order that any

relief may be made available by the Fall school term

and the Court accordingly specially calendared and

tried the issues on May 9,10 and 13th.

In response to plaintiffs’ further request for an early

ruling herein the following findings of fact and conclu

sions of law under Rule 52 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure are made on a preliminary basis. The court

will issue its formal opinion and final findings within

the next thirty days (R. 226).

Thus the court announced that the findings and conclu

sions were preliminary, not that the order or decree was

preliminary. Also it promised to issue at a later time a

formal opinion and findings, not a final order, decree, or

judgment. 6

6) Nothing in the preliminary findings of fact and con

clusions of law indicates that the order of May 13 was

designed to be a denial of preliminary relief only. The

8

first sentence of the preliminary findings states: “ This is

a school desegregation case in which plaintiffs ask a man

datory injunction requiring total integration of the schools

administered by the defendants” (R. 225). It was this in

junction, not merely the preliminary injunction which the

order of the same day denied.

7) Between May 13 and June 28 no proceedings were

held in the district court which could indicate a difference

in function between the two orders. (On May 31, the dis

trict court followed this Court’s order of May 24 and

granted an injunction pending appeal. This, however, is

not relevant to the meaning of the order of May 13.) If

only the question of preliminary relief had been decided

on May 13, presumably further proceedings would have

been necessary before a ruling on the permanent injunction

would be appropriate. In fact, the issues were identical:

if the interveners’ psychological evidence was legally ade

quate to bar the plaintiffs’ request for preliminary relief,

by the same reasoning it would bar permanent relief. At

the trial, the plaintiffs declined the opportunity to rebut the

interveners’ evidence (Tr. 261-62). Thus, no further pro

ceedings were had and none were necessary, because the

two orders ruled on the same issues and served the same

function—denial of all relief.1

In summary, all of the circumstances of this case point

inevitably to the conclusion that the order of May 13, from

which this appeal was duly taken, was the order denying

all relief, both preliminary and permanent. Because of the

1 This factor alone is sufficient to distinguish the ease cited

by defendant-appellees, Dempsey v. Guaranty Trust Co., 131 F. 2d

103 (2d Cir. 1942), cert, denied, 318 U. S. 769. In that ease follow

ing the ruling on a preliminary injunction a motion to dismiss the

case was made by defendant, and then the case was dismissed.

9

need for a speedy decision, the district court reserved the

opportunity to explain its reasons, which it did on June 28

when it also formalized the order. The order of June 28

did not differ in substance from the earlier, appealable

order of May 13, and an additional appeal from the later

order was unnecessary and would have been meaningless.2

In addition, it must be observed that to dismiss this ap

peal would result in manifest injustice. The order of June

28 appeared 46 days after the order of May 13, and well

after this Court had acted on the appeal. In order to pre

sent a complete record to this Court the formal opinion

and final findings were designated for inclusion in this

record, and the order entered on June 28 is before this

Court. Surely, the plaintiffs were justified in believing that

the action taken by the district court on June 28 was of no

further significance.

In any event, the plaintiffs have shown no inclination to

drop this case. Since June 28, they have objected to the

Board of Education’s plan (Supp. R. 28), participated in a

hearing on the plan (Supp. R. 31), appealed from the dis

trict court’s order of July 29 refusing to pass on the merits

of the plan (Supp. R. 117), opposed a petition for writ of

certiorari filed in the Supreme Court by interveners to

review this Court’s order of May 24, and continued to prose

cute this appeal. In Carter v. Campbell, 285 F. 2d 68 (1960),

this Court held that similar factors constituted a sufficient

substitute for a formal notice of appeal.

2 Where there is some question as to which of two papers is

appealable, this Court has followed a liberal interpretation of the

Federal Rules. See Bates v. Batte, 187 F. 2d 142 (5th Cir. 1951);

Carter v. Campbell, 285 F. 2d 68 (5th Cir. I960); Blanchard v.

Commonwealth Oil Co., 294 F. 2d 834 (5th Cir. 1961).

10

II.

The Desegregation Plan Is Constitutionally Inadequate.

On the present appeal, the order of May 13 must he re

versed, with a direction to the district court to enjoin the

operation of a segregated school system in Chatham County.

Because the Board of Education has submitted a plan on

which a full hearing has been held in the district court, this

Court is in a position to designate with specificity the scope

of relief to which appellants are entitled.

The plan submitted by the Board of Education is grossly

inadequate to achieve any meaningful desegregation.

Nearly a decade after the Supreme Court’s decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 4S3 (1959) the plan

provides for desegregation at the rate of one grade per

year. The Court’s recent opinions in Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 and Goss v. Board of Education of

the City of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683, make it clear that

those who have failed to make a prompt and reasonable

start cannot further delay complete desegregation for an

other eleven or twelve years. See Jackson v. School Board

of City of Lynchburg, 321 P. 2d 230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963).

To make things worse, the Board of Education has be

gun the plan at the top, the twelfth grade, rather than the

bottom. There is some question whether this feature of the

plan complies with this Court’s order of May 24, 1963

(Supp. R. 8). In any event, by making the transfer plan

applicable to the twelfth grade, the Board assures a mini

mum of desegregation because adolescent students already

established in one school are naturally reluctant to transfer

to another. Beginning with the lower grades would allow a

greater degree of desegregation with a minimum of admin

istrative difficulty.

11

The Board of Education further perpetuates the exist

ing pattern of segregation by refusing to allow students en

tering the school system for the first time to be assigned to

schools on a nonracial basis. See Augustus v. Board of

Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862, 869 (5th Cir. 1962).

Surely, that modest measure would entail no disruption of

existing administrative arrangements.

As to those grades that are “desegregated” under the

Board’s plan, there is only the most limited desegregation.

Dual zone lines continue to be employed as a basis for

initial assignment. There are six high schools in the

county, one white school and one Negro school in each of

three districts (Supp. R. 77). In the absence of some show

ing by the Board, which under the second Brown decision,

349 U. S. 294, bears the burden of proof, that the estab

lishment of unitary zone lines would be administratively

impracticable, there is no reason to allow the restriction

of desegregation to the allowance of transfers. Augustus

v. Board of Public Instruction, supra; Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962); North-

cross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302

F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962).

Finally, the transfer provisions of the plan place ob

stacles before those who desire to exercise their constitu

tional rights. There is no public announcement of the avail

ability of transfers (Supp. R. 81-82). Transfer applica

tions are not made readily available to the students, but

must be obtained in person from the principal or the Super

intendent (Supp. R. 23). Both parents must sign the ap

plication and have it notarized (Supp. R. 23). A separate

application is necessary for each child (Supp. R. 23). All

applications must be submitted within a fifteen-day period,

normally by May 15, well in advance of the school year

(Supp. R. 22). The Superintendent may require interviews

12

with each applicant and his parents (Supp. R. 23) and can

base his decision on any of seventeen different criteria

(Supp. R. 21-22). If turned down by the Superintendent,

the applicant may appeal to the Board of Education (Supp.

R. 23-26).

One indication of the effectiveness of this plan is the

results obtained in the first year of its implementation. In

a system with approximately 2,000 students in the twelfth

grade alone, of whom approximately 30 per cent are Negro

(Supp. R. 67-68), only 19 Negro twelfth-graders are attend

ing school with whites (Appellee’s Brief, p. 3). No white

students are attending Negro schools, and there is no de

segregation whatever below the twelfth grade. Nor has

there been any desegregation of teaching or administrative

staffs. These are the fruits of the Board’s desegregation

plan, and the only explanation in the record is inertia and

minimal compliance.

It is submitted that the Board should be directed to

bring in a plan providing, at the very least, that transfers

be allowed in all grades on a reasonable, nonracial basis;

that students entering the system for the first time be

assigned without regard to race; and that school zone lines

be redrawn on a nonracial unitary basis as to the first four

grades in September 1964, and as to at least two additional

grades per year thereafter beginning with September 1965.

13

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below should

be reversed and the trial court directed to issue an in

junction as requested above.

Respectfully submitted,

C onstance B ak er M otley

J ac k Greenberg

D errick A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

B. Clarence M ayfield

910 West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

E. H. Gadsden

458% West Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

D onald L. H ollow ell

85914 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

14

Certificate of Service

T h is is to cebtify that on the ....... day of April, 1964 I*

served a copy of the foregoing Appellants’ Reply B^ef and

Supplemental Brief upon Basil Morris, P. 0. Box 396,*

Savannah, Georgia and E. Freeman Leverett, Deputy As- . *

sistant Attorney General, Starte of Georgia, Elbft-ton, Gebr- •.

gia, Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants,• and Carter^'-

Pittman, P. 0. Box 891, Dalton, ^ org ia , J. Walter Cowart,

504 American Building, Savan^ih, Georgia, Charles J.

Block, P. 0. Box 176, Macon, • Georgia, and George S. ® ' •

Leonard, 1730 K Street, N. W., Washington 6, D. C., At--1* ^

torneys for Interveners-Appellees, by mailing copies to

them at the above addresses via United States mail, air

mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for AppeMmts