United States v. Richardson, Jr. Brief for Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 23, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Richardson, Jr. Brief for Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees, 1988. 496774c4-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/908fcb7a-4f6d-4be5-bd47-f487dfa44d7a/united-states-v-richardson-jr-brief-for-plaintiffintervenors-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

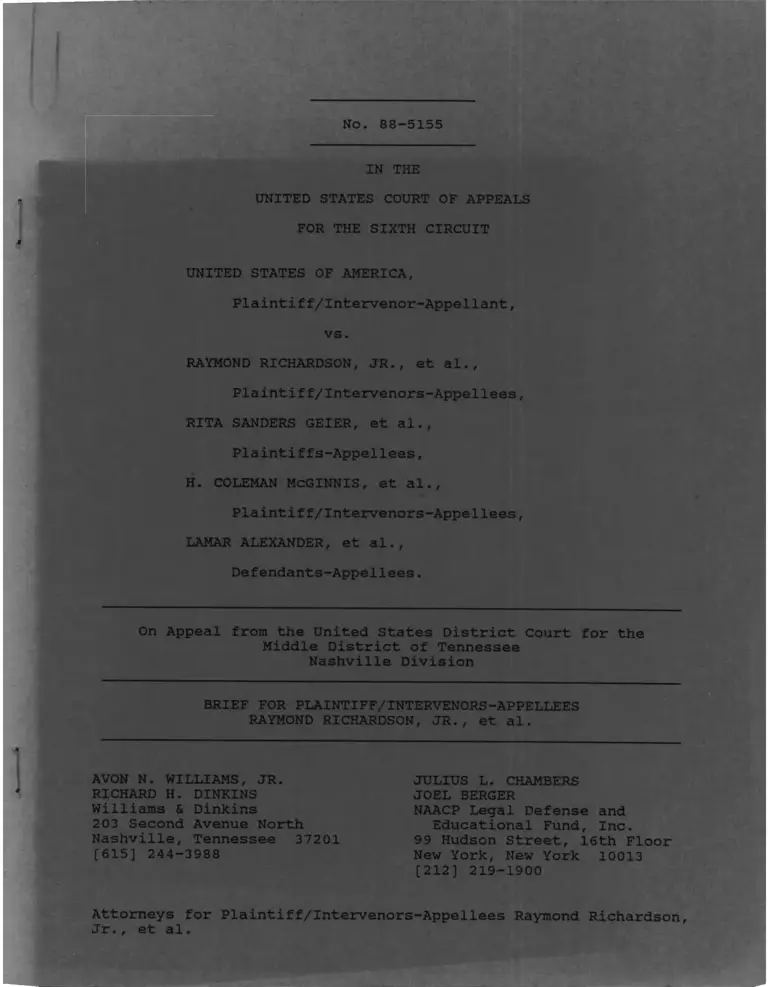

No. 88-5155

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff/Intervenor-Appellant,

vs.

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.,

Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees,

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

H. COLEMAN McGINNIS, et al.,

Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees,

LAMAR ALEXANDER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Tennessee

Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF/INTERVENORS-APPELLEES

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

RICHARD H. DINKINS

Williams & Dinkins

203 Second Avenue North

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

[615] 244-3988

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JOEL BERGER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

[212] 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees Raymond Richardson,

Jr., et al.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

QUESTION PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

I. Course of Prior Proceedings 2

II. Statement of Facts 6

ARGUMENT 11

THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY AWARDED ATTORNEYS'

FEES AND COSTS TO THE PREVAILING PARTIES ON THE

JUSTICE DEPARTMENT'S UNSUCCESSFUL APPEAL IN

GEIER V. ALEXANDER. 801 F.2d 799 (6TH CIR.

1986), AN APPEAL IN WHICH THE DEPARTMENT SOUGHT

INVALIDATION OF AN AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAM

AIMED AT ELIMINATING THE VESTIGES OF STATUTORY

SEGREGATION IN TENNESSEE'S SYSTEM OF PUBLIC

HIGHER EDUCATION ................................... 11

CONCLUSION 23

i

CASES PAGE

Akron Center for Reproductive Health v. City of Akron,

604 F.Supp. 1268 (N.D. Ohio 1984).................... 14, 16

Baker v. City of Detroit, 504 F.Supp. 841 (E.D. Mich.

1980) '..................................................... ..

Bazemore v. Friday, ____ U.S. ____, 92 L.Ed.2d 315

(1986) .................................................. 5

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) . 9, 11-16

City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d

448 (2d cir. 1974) ..........................................

Firefighters v. City of Cleveland, ____ U.S. ____, 92

L.Ed.2d 405 (1986) 5

Geier v. Alexander, 593 F.Supp. 1263 (M.D. Tenn. 1984); . . . . 2

Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th

Cir. 1986) ................................. 1-3, 5, 11, 12,

20

Geier v. Blanton, 427 F.Supp. 644 (M.D. Tenn. 1977) .......... 2

Geier v. Dunn, 337 F.Supp. 573 (M.D. Tenn. 1972) 2

Geier v. University of Tennessee, 597 F.2d 1056

(6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S.

886 (1979)..................................................

Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446 U.S. 754 (1980).................. 18, 19

Haycraft v. Hollenbach, 606 F.2d 128 (6th Cir. 1979) . . 13, 16, 18

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983) .................... 23

Hewitt v. Helms, ____ U.S. ____, 96 L.Ed.2d 654 (1987) . . . 17, 19

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education, 773

F.2d 677 (6th Cir. 1985) (en banc).................... 7 , 19

Kentucky v. Graham, 473 U.S. 159 (1985) .................. 17, 18

Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122 (1980) .......................... 1 7

Richardson v. Blanton, 597 F.2d 1078 (6th Cir. 1979).......... 2

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

ii

CASES PAGE

Robideau v. O'Brien, 525 F.Supp. 878 (E.D. Mich. 1981) ........ 14

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F.Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968) . . . . 2

Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, ____ U.S. ____, 92

L.Ed.2d 344 (1986) ....................................... 5

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ............ 14, 16, 18, 20

Tarter v. Raybuck, 742 F.2d 977 (6th Cir. 1984) .............. 12

Vulcan Society of Westchester County, Inc., v. Fire

Department of the City of White Plains, 533

F.Supp. 1054 (S.D.N.Y. 1982) ............................ 14

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267 (1986) . . . 4

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. §2412 ( b ) .........................................21, 22

42 U.S.C. §1988 ............................... 14, 16, 17, 20-22

OTHER AUTHORITIES

House of Representatives Report No. 94-1558, 94th

Congress, Second Session (1976) .......................... 12

Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorneys' Fees (1981)

at 42-44 ................................................. 15

Senate Report No. 94-1011, 94th Congress, Second

Session (1976) ................................... 14, 19, 21

Tamanaha, The Cost of Preserving Rights: Attorneys'

Fee Awards and Intervenors In Civil Rights

Litigation, 19 Harv. Civil Rights-Civil Liberties

L. Rev. 109 (1984) 15

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS

_______AND FINANCIAL INTEREST_______

Pursuant to 6th Cir. R. 25, Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees

Raymond Richardson, Jr., et al. make the following disclosure:

1. Is said party a subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly owned

corporation? No

If the answer is YES, list below the identity of the parent

corporation or affiliate and the relationship between it and

the named party:

2. Is there a publicly owned corporation; not a party to the

appeal, that has a financial interest in the outcome? No

If the answer is YES, list the identity of such corporation

and the nature of the financial interest:

Date

JOEL BERGER

6CA-1

7/86

iv

No. 88-5155

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff/Intervenor-Appellant,

vs.

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.,

Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees,

RITA SANDERS GEIER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

H. COLEMAN MCGINNIS, et al.,

Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees,

LAMAR ALEXANDER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Tennessee

Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF/INTERVENORS-APPELLEES

RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR., et al.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the district court properly awarded attorneys7 fees

and costs to the prevailing parties on the Justice Department's

unsuccessful appeal in Geier v. Alexander. 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir.

1986) , an appeal in which the Department sought invalidation of

an affirmative action program aimed at eliminating the vestiges

of statutory segregation in Tennessee's system of public higher

education?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Course of Prior Proceedings

The history of this case is well known to the Court and is

succinctly summarized at the outset of Chief Judge Lively's

opinion in Geier v. Alexander. 801 F.2d 799, 800-02 (6th Cir.

1986), the unsuccessful Justice Department appeal for which fees

were awarded below. We will not burden the Court with another

recitation of the long and often tortured history of the

litigation, which to date has produced four published district

court opinions1 and three published appellate opinions.2

For present purposes, it suffices to state that in 1984,

after 16 years of courtroom battles, all of the parties except

the United States agreed to a comprehensive consent decree

requiring numerous new desegregation programs throughout

Tennessee's public higher education system. The decree settled

1 Geier v. Alexander. 593 F.Supp. 1263 (M.D. Tenn. 1984);

Geier v. Blanton. 427 F.Supp. 644 (M.D. Tenn. 1977) ; Geier v.

Dunn, 337 F.Supp. 573 (M.D. Tenn. 1972) ; Sanders v. Ellington.

288 F.Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968).

2 Geier v. Alexander, supra; Richardson v. Blanton. 597

F.2d 1078 (6th Cir. 1979); Geier v. University of Tennessee. 597

F.2d 1056 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied. 444 U.S. 886 (1979).

2

three outstanding motions for further relief, filed by two groups

of plaintiff-intervenors (the Richardson intervenors and the

McGinnis intervenors) and the original plaintiffs, which had been

pending for several years.

The Justice Department, which had been a plaintiff-

intervenor since 1968,3 had filed no motion for further relief

and had not responded to any of the motions for further relief

pending in the district court. Nonetheless, the Department

utilized its historic status as an intervenor to oppose most of

the programs of the settlement agreement. On August 9, 1984, the

Department filed a memorandum claiming that these programs (i)

contained too many race-conscious remedies, (ii) contained too

many percentage goals and timetables, (iii) were based upon

insufficient evidence of continuing vestiges of Tennessee's dual

system of public higher education and (iv) were based upon

insufficient evidence that any individual black person in

Tennessee was today the individual victim of discrimination in

public higher education.

The district court heard oral argument on the Justice

Department's objections and rejected them, advising Assistant

Attorney General Reynolds that the Department's position "offends

the intelligence of everybody in this room." Transcript of

August 13, 1984, at 40. See Geier v. Alexander. 593 F.Supp. 1263

The complaint in intervention was signed by Attorney

General Ramsey Clark in the administration of President Lyndon B.

Johnson.

3

(M.D. Tenn. 1984)(opinion approving Stipulation of Settlement

over the Department's objection) . The Department appealed, and

filed a Civil Pre-Argument Statement in this Court on December 6,

1984 (No. 84-6055) attacking the entire settlement agreement on

the ground that it "utilizes racial classifications and accords

preferential treatment to persons not identified as victims of

discrimination." It was not until the filing of its opening

brief, on June 14, 1985, that the Department narrowed the target

of its theories to a single program: the pre-professional

training program of Paragraph II(N) of the Stipulation.

Shortly before oral argument, the Supreme Court of the

United States rejected the Department's "victim specificity"

analysis in the context of an employment discrimination case.

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education. 476 U.S. 267 (1986) . The

plurality opinion in Wygant also analogized racial preferences in

hiring to racial preferences in professional school admission,

finding both to be valid means of remedying past discrimination.

476 U.S. at 282-83 & n. 11. Nonetheless, the Department filed a

supplemental brief in this Court claiming that Wygant supported

its position or at least did not conclusively resolve the matter

against the Department (see, e.g.. appellant's supplemental brief

in No. 84 — 6055 at 7 & n.5, 10—11 & n.6) . Four days after the

supplemental brief was filed, however, the Supreme Court rejected

the Department's "victim specificity" theories in two more

4

employment discrimination cases.4 Accordingly, as this Court

later observed, the Department "did not press its 'victim

specificity' theory in oral argument" of the appeal. Geier v.

Alexander. supra. 801 F.2d at 803.

Nonetheless, instead of conceding defeat the Department

constructed an entirely new theory of the case at oral argument,

based upon dicta in another recent Supreme Court decision,

Bazemore v. Friday. ___ U.S. ___ , 92 L.Ed.2d 315 (1986). This

Court rejected the claim. 801 F.2d at 804-05. The Department

apparently had subsequent second thoughts about the potential of

Bazemore. as it did not seek certiorari.

The Justice Department also claimed that the district court

had erred in failing to conduct an evidentiary hearing on the

Department's objections to the Stipulation of Settlement. This

Court rejected that argument as well, stating that the following

passage from a Second Circuit opinion aptly described the

Department's conduct:

In general the position taken by the

objectors is that by merely objecting, they

are entitled to stop the settlement in its

tracks, without demonstrating any factual

basis for their objections and to force the

parties to expend large amounts of time,

money and effort to answer their rhetorical

questions, notwithstanding the copious

discovery available from years of prior

litigation and extensive pre-trial

proceedings. To allow the objectors to

̂ Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC. ___ U.S. ___, 92 L.Ed.2d

344 (1986); Firefighters v. City of Cleveland. U.S. , 92

L.Ed.2d 405 (1986) .

5

disrupt the settlement on the basis of

nothing more than their unsupported

suppositions would completely thwart the

settlement process.

801 F.2d at 809, quoting from City of Detroit v. Grinnell Coro..

495 F.2d 448, 464 (2d Cir. 1974).

In sum, the Court was highly critical of the Department's

entire performance in this proceeding and of the about-face which

that performance represented:

In the early years it was the United States

that exhorted the court to broaden its

remedial orders while the state sought to

restrict them. At the very time the state

became convinced that its earlier efforts had

failed to eliminate the vestiges of its past

discriminatory practices, the Department of

Justice was urging the court to pull back—

a truly ironic situation.

801 F.2d at 809.

II. Statement of Facts

On October 25, 1984 — 30 days after the district court

approved the Stipulation of Settlement — plaintiff-intervenors

Raymond Richardson, Jr., et al. filed a protective motion for

attorneys fees and costs in compliance with Local Rule 13 (e) of

the Middle District of Tennessee. The motion alleged that the

Richardson intervenors were prevailing parties, but did not

specify the parties against whom fees were sought.

6

Further proceedings on the issue of fees necessarily awaited

the outcome of the Justice Department's appeal.5 This Court

rendered its decision of affirmance on September 5, 1986, and its

mandate issued on September 3 0.6 After the deadline for the

filing of a certiorari petition had passed, the private plaintiff

groups began negotiating with the State over the question of fees

for work done on the various motions for further relief. On

January 30, 1987, the Richardson intervenors filed a 37-page

document entitled "First Supplement To Protective Motion For An

Award of Counsel Fees and Costs." The document presented a

detailed accounting of hours worked and costs incurred from 1980-

86, including hours and costs pertaining to the Justice

Department's unsuccessful appeal.

On February 18, 1987, the parties appeared before the

district court on a related matter, an application for fees by

the original plaintiffs against a would-be intervenor named

Terrell who had been denied intervention and whose appeal

challenging that determination had been dismissed. Docket no. 6,

As noted previously, the Department had challenged the

validity of the entire settlement agreement in the district court

and in its Civil Pre-Argument Statement to this Court. See pp 3-

4, supra. Although the Department's brief subsequently narrowed

the scope of its appeal, the pendency of the appeal created

sufficient uncertainty as to preclude any final resolution of the

question of fees.

6 The mandate concluded with the words "No costs taxed."

Under this Court's decision in Kelley v. Metropolitan Countv

Board of Education. 773 F.2d 677, 681-82 (6th Cir. 1985) (en

banc) , that statement had no affect whatsoever on the subsequent

proceedings before the district court.

7

p. 2. During the course of that proceeding the court asked the

parties to brief the question of whether fees could be assessed

against the United States, noting that the federal government's

unsuccessful appeal had "caused a lot of people ... to spend a

lot of time and effort and energy and incur a lot of costs." id.

at 3. Shortly thereafter the State and McGinnis intervenors both

filed motions for fees against the United States. Docket nos. 7,

9. The Richardson intervenors took the position that their 1984

protective motion covered the situation, but as a precaution

filed a second motion specifically requesting fees from the

United States for the Justice Department's unsuccessful appeal.

Docket no. 11.7

By order entered May 18, 1987, the district court approved a

settlement agreement between the Richardson intervenors and the

State for all district court work performed between 1980-86. On

May 26, 1987, the Richardson attorney who was lead counsel on the

appeal for all the plaintiff-appellee groups filed an attorneys'

fees affidavit limited solely to work performed on the appeal.

Docket no. 13. See also Docket no. 17 (affidavit of Richardson's

Nashville attorney).

On September 16, 1987, the Justice Department filed a

response denying all fees liability, primarily on the theory that

the Department was a plaintiff in this case and that fees cannot

The original plaintiffs had sought fees against the

United States in a motion filed on January 5, 1987. Docket No.

2 .

8

be awarded against any plaintiff unless the strict standard of

Christiansburcr Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412 (1978) has been

met. Docket no. 23. The Richardson intervenors filed a reply

with several exhibits on September 29, 1987. Docket no. 27. In

view of the Department's resistance to paying any fees, the

district court heard oral argument in Nashville on October 27,

1987. At the conclusion of that proceeding the court (Hon.

Thomas A. Wiseman, Jr.) ruled that it would award fees against

the United States, stating:

The Court finds Christiansburg simply does

not apply in this case. The Christiansburg

standards and statutes, congressional

history, all indicate that it's designed to

protect and to prevent the chilling of the

assertion of rights by private Attorney

Generals, by citizens trying to assert their

constitutional rights and the reluctance of

this Court and all Courts to award

defendants' fees against plaintiffs is to

prevent the chilling of such rights. There's

absolutely no element in this case where that

awarding of fees against the United States

could chill anybody's activities in the

assertion of civil rights.

This Court might well find that the

actions of the Justice Department in this

case were frivolous, vexatious and without

foundations. I have not made such a finding

and won't make such a finding because it's

unnecessary. The parties who applied for

fees in this case are, in fact, the

prevailing party before the Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals.

Consequently the fee applications will be

granted.

Docket no. 35 17-18. Following submission of supplemental

affidavits by the Richardson intervenors (docket nos. 30 and 31)

9

and other parties (docket nos. 28, 29, 32, 33 and 34) documenting

additional hours and costs incurred as a result of the Justice

Department's opposition to the payment of fees,8 the Court

entered its order on November 13, 1987 (docket no. 36). The

Court awarded $63,3 67.89 to counsel for the Richardson

intervenors ($55,355.39 to the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. and $8,012.50 to Richard Dinkins, Esq.),

$19,531.46 to the State of Tennessee, $5,500.01 to counsel for

the McGinnis intervenors ($3,983.51 to Aleta Arthur, Esq. and

$1,516.50 to John Norris, Esq.), and $2,340 to counsel for the

original plaintiffs.

The Justice Department filed a timely notice of appeal on

January 15, 1988 (docket no. 37). On January 26, 1988, the

district court granted the Department's motion for a stay pending

appeal (docket no. 39).

Nearly all of the fees and costs sought by the

Richardson intervenors in their supplemental submission were

occasioned by the need to respond to the Justice Department's

position, and by the preparation, travel and courtroom time

expended in connection with the judicial proceeding conducted in

Nashville to consider the Department's views.

10

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY AWARDED

ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS TO THE

PREVAILING PARTIES ON THE JUSTICE

DEPARTMENT'S UNSUCCESSFUL APPEAL

IN GEIER V. ALEXANDER. 801 F.2d 799

(6TH CIR. 1986), AN APPEAL IN WHICH

THE DEPARTMENT SOUGHT INVALIDATION

OF AN AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PROGRAM

AIMED AT ELIMINATING THE VESTIGES

OF STATUTORY SEGREGATION IN

TENNESSEE'S SYSTEM OF PUBLIC HIGHER

EDUCATION

A.

The Justice Department's position on this appeal is based

upon the mistaken assumption that the principle of Christiansbura

Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412 (1978), applies to the Depart

ment's behavior in this case. Nothing could be farther from the

truth.

Although the United States entered this case in 1968 as a

plaintif f-intervenor, and generally pursued desegregation

objectives in the litigation during the 1970's, its role changed

drastically with the advent of the burrent presidential

administration in 1981. The Justice Department (i) was the only

plaintiff group not to file a motion for further relief in the

early 1980's, (ii) did not file a reply to the motions for

further relief filed by the other parties, (iii) was the only

party in the case to oppose the settlement, largely on the basis

of "reverse-discrimination" and "victim-specificity" theories

11

which placed the Department in opposition to the desegregation

objectives of all other parties including the State of Tennessee,

and (iv) tied up the other parties in litigation for another two

years by appealing the district court's approval of the

settlement, only to have its position rejected by a unanimous

panel of this Court (Lively, C.J., Milburn & Peck, JJ.) in Geier

v. Alexander. 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986). This Court

recognized and criticized the Justice Department's about-face in

its opinion affirming the district court's approval of the

consent decree. Geier v. Alexander, supra. 801 F.2d at 809,

quoted at p. 6, supra.

In light of this history, it is simply ludicrous for the

Justice Department to attempt to hide behind the Christiansbura

standard. Christiansbura was intended to effectuate Congress'

policy of promoting enforcement of the civil rights laws by

private parties, and to insure that such parties would not be

inhibited by fear that the defendants, who are often government

agencies with greater resources, would be able to recover fees

whenever the plaintiffs do not prevail. See Christiansbura

Garment Co. v. EEOC, supra. 434 U.S. at 419, 422; Tarter v.

Raybuck, 742 F.2d 977, 984-85 (6th Cir. 1984). See also House of

Representatives Report No. 94-1558, The Civil Rights Attorneys'

Fees Awards Act of 1976. 94th Congress, Second Session (1976), at

12

7.9 Christiansburcr certainly was not designed to insulate

governments from fee awards when they behave as defendants in

civil rights litigation, aligning themselves against parties who

seek to enforce desegregation.

The fact that the United States is technically a plaintiff-

intervenor in this case is irrelevant. The Justice Department in

recent years behaved exactly as a defendant-intervenor, such as a

union seeking to invalidate an affirmative action settlement in

an employment discrimination case or a local official seeking to

oppose a school desegregation decree. This Court has squarely

held that private civil rights litigants are entitled to recover

fees from such a party. Havcraft v. Hollenbach. 606 F.2d 128,

133 (6th Cir. 1979) :

It cannot be gainsaid that in interposing his

desegregation plan, appellant caused the

district court and appellees to expend

substantial time and energy litigating an

issue that had already been resolved by the

prior mandate of this court.... Accordingly,

an award of fees in the present case can be

justified on the ground that appellant's

intervention amounted to obstinacy in

resisting appellees' realization of their

clearly defined legal rights.

"• • • governmental officials are frequently the

defendants in cases brought under the statutes covered by ...

[the Act]. Such governmental entities and officials have

substantial resources available to them through funds in the

common treasury, including taxes paid by the plaintiffs

themselves. Applying the same standard of recovery to such

defendants would further widen the gap between citizens and

government officials and would exacerbate the inequality of

litigating strength."

13

Numerous lower courts, both within this Circuit and elsewhere,

have held likewise. See. e.g.. Akron Center for Reproductive

Health v. City of Akron. 604 F.Supp. 1268 (N.D. Ohio 1984);

Vulcan Society of Westchester County, Inc.. v. Fire Department of

the City of White Plains. 533 F.Supp. 1054 (S.D.N.Y. 1982);

Robideau v. Obrien. 525 F.Supp. 878 (E.D. Mich. 1981); Baker v.

City of Detroit. 504 F.Supp. 841 (E.D. Mich. 1980).

It has long been recognized that an award of attorneys' fees

under 42 U.S.C. §1988 does not depend upon the technical status

of the party seeking fees or of the party against whom fees are

sought. In passing the Act, Congress explicitly noted that in

some cases a defendant or defendant-intervenor may be the one

enforcing the civil rights laws and a plaintiff or plaintiff-

intervenor may be the one opposing them, citing as an example

Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 U.S. 1 (1948) . Senate Report No. 94-

1011, Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act. 94th Congress,

Second Session (1976), at 4 n.4. Congress hardly intended to

allow plaintiffs such as those in Shelley, who sued to enforce a

racially restrictive covenant, to hide behind the Christiansburg

standard. In complex cases with numerous intervenors, courts

should look to the actual role played by a party rather than

focusing upon its nominal status. As the court observed in Baker

v. City of Detroit. supra. 504 F.Supp. at 850, a "reverse

discrimination" case in which unsuccessful plaintiffs were

required to pay the fees of defendant-intervenors:

14

In the case at bar, it happens that the

intervenors were defendants. They could just

as easily have been plaintiffs or intervening

plaintiffs had they, the United States, or

other black officers filed suit against the

City. The Civil Rights Attorney's Fee Act is

to be liberally construed to effectuate its

purposes. See Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. of

Memphis Schools. 611 F.2d 624, 632-33 (6th

Cir. 1979) , cert, denied. 447 U.S. 911, 100

S.Ct. 2999, 64 L.Ed.2d 862 (1980). The

procedural posture of the case should not be

dispositive.

See also Larson, Federal Court Awards of Attorneys' Fees (1981)

at 42-44 and cases cited therein; Tamanaha, The Cost of

Preserving Rights: Attorneys' Fee Awards and Intervenors In

Civil Rights Litigation. 19 Harv. Civil Rights-Civil Liberties L.

Rev. 109, 130 (1984)("distinctions between defendant-intervenors

and plaintif f-intervenors based entirely on the side of

intervention raises fortuitous circumstance above substance").

In this case the Richardson intervenors, McGinnis

intervenors, original plaintiffs and defendants were all aligned

in this Court as appellees fighting for the desegregation

objectives of the Stipulation of Settlement. The Justice

Department stood alone as appellant seeking to thwart those

objectives. Under these circumstances the Justice Department is

not entitled to the benefit of Christiansburg. and the prevailing

appellees should be awarded fees in accordance with the

objectives of the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Act.

15

B.

The Justice Department's brief on this appeal presents a

novel argument not advanced below. The Department claims that it

is entitled to the benefit of Christiansburg not just because of

its nominal status as a plaintiff-intervenor, but also because it

was not held liable for anything on the merits and no relief was

assessed against it.

The argument is patently frivolous. The unsuccessful

plaintiffs in Shelley v. Kraemer. supra. were not held liable for

anything on the merits in that case either, and no relief was

assessed against them; they simply were unsuccessful in their

effort to enforce a racially restrictive covenant. Nonetheless,

the legislative history of 42 U.S.C. §1988 clearly establishes

the intent of Congress to make such unsuccessful parties pay

attorneys' fees to the prevailing parties. Similarly, the party

whom this Court required to pay fees in Havcraft v. Hollenbach.

supra. was not liable for anything on the merits and no relief

was assessed against him. The same is true of the parties

required to pay fees in all of the other cases cited at p. 14,

supra. See. e.g.. Akron Center for Reproductive Health v. City

of Akron, supra. 604 F.Supp. at 1273 (N.D. Ohio 1984).

Most settlement agreements, including the 1984 Stipulation

in this case, specify that the defendant does not admit any

liability. Many cases are settled informally without any written

agreement at all, let alone a finding of merits liability. Yet

16

Congress explicitly stated that the parties whose rights are

vindicated in this fashion are entitled to fees, and the Supreme

Court has so held. Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122, 129 (1980);

Hewitt v. Helms, ___ U.S. ___, 96 L.Ed.2d 654, 661 (1987).

The Justice Department's argument is based upon a distorted,

out-of-context reading of dicta from the Supreme Court's opinion

in Kentucky v. Graham. 473 U.S. 159 (1985) . The sole question

presented by that case, set forth in the opening paragraph of

Justice Marshall's opinion for a unanimous Court, was

whether 42 U.S.C. §1988 allows attorney's

fees to be recovered from a governmental

entity when a plaintiff sues governmental

employees only in their personal capacities

and prevails.

473 U.S. at 161. The plaintiffs in Graham had sued several

defendants in their personal capacities, and had added the

Commonwealth of Kentucky as a defendant solely for purposes of

obtaining fees. Id. at 162. It was in this context that the

Supreme Court, in the course of holding Kentucky non-liable for

fees, stated that "[t]here is no cause of action against a

defendant for fees absent that defendant's liability for relief

on the merits." Id. at 170 (emphasis added). This language in

Graham obviously was not intended to address situations in which

a plaintiff or plaintiff-intervenor might be responsible for

fees, since such parties are rarely, if ever, liable for anything

on the merits. The Court in Graham had no occasion even to

examine, let alone rule upon, the kind of case envisioned by the

17

Senate Report's reference to Shelley v. Kraemer. supra or the

kind of case decided by this Court in Havcraft v. Hollenbach.

supra. Graham merely held that in a case against several

defendants where only some are liable on the merits, the non-

liable defendants are not responsible for fees.10 That is a

simple proposition which has absolutely nothing to do with this

case.

The Department relies upon two other Supreme Court cases

which are even less relevant than Graham. In Hanrahan v.

Hampton, 446 U.S. 754 (1980), the parties seeking fees had "not

prevailed on the merits of any of their claims" against anybody,

id. at 758, but had merely won reversal of a directed verdict

against them. In Hewitt v. Helms. ____ U.S. ____, 96 L.Ed.2d 654

(1987) , the sole issue was "whether a party who litigates to

judgment and loses on all of his claims can nonetheless be a

'prevailing party' for purposes of an award of attorney's fees."

Id. at 659. Here, by contrast, there is no dispute that the

Richardson intervenors are "a prevailing plaintiff." Brief for

Appellant (hereinafter "Br. App.") at 11. They secured a far-

reaching settlement from the State, and then successfully fought

off a strenuous effort by the Department to invalidate one of the

key components of that settlement. There is not even a tenuous

resemblance between the Richardson intervenors in this case and

10 In Graham the Commonwealth was not only a non-liable

defendant but had been dismissed as a defendant early in the

proceedings. 473 U.S. at 162.

18

the plaintiffs in Hanrahan and Hewitt.11

C.

The Department further claims that merely by virtue of its

presence in this case — even though it was on the side opposing

further desegregation measures — the private plaintiffs are not

entitled to fees. Br. App. at 14 and 17-18. The argument is

truly Orwellian.

Although the legislative history refers to private civil

rights plaintiffs as "private attorney general[s]," Sen. Rept.

-LX The Department suggests that the State of Tennessee

should pay the fees at issue here because those fees "were most

directly a consequence of the defendants7 violation of federal

law and failure previously to remedy that violation" (Br. App. at

17). This statement is highly disingenuous. The two years of

time-consuming appellate litigation from 1984-86 were "most

directly" a consequence of the Justice Department's decision to

mount an appeal.

We do not deny that the State was indirectly responsible for

the circumstances that led to the appeal, and agree with

appellants that there is authority in this Circuit for imposing

fees liability upon the State under such circumstances. Kelley

v. Metropolitan County Board of Education. 773 F.2d 677, 684-85

(6th Cir. 1985) (en banc). See Transcript of February 18, 1987

(docket no. 6) at 4-5; plaintiffs' reply (docket no. 27) at 6 n.

2 (preserving issue for further review). If this Court were to

reverse the award of fees against the United States, a remand for

assessment of fees against the State would indeed be the

appropriate course of action. Nonetheless, we agree with Judge

Wiseman that it is far more equitable to require the United

States to pay for the appeal. Transcript of February 18, 1987

(docket no. 6) at 5. After all, the State resisted the appeal,

co-argued with the Richardson intervenors' counsel as an

appellee, and helped us to prevail against the Justice

Department. Unless this Court determines that there is no other

way of compensating the plaintiff groups for their appellate

work, the State should not have to pay for an appeal which it opposed.

19

No. 94-1011, supra, at 3, nowhere did Congress even hint that

such plaintiffs should have any less entitlement to fees merely

because the United States is also a party. The Department does

not cite a single case so holding, even though there have been

countless civil rights cases since passage of 42 U.S.C. §1988 in

which both the Department and private plaintiffs have been

allies. But what makes the Department's argument especially

silly here is that it was not enforcing the civil rights

objectives of the statute; it was opposing them. This Court said

so in Geier v. Alexander, supra. 801 F.2d at 809.

The Department apparently takes the position that any time

it is a party to a civil rights case — even if its position is

against civil rights enforcement, and even if that position is

rejected by the courts — the prevailing private plaintiffs

cannot obtain fees because it is the Department which "has been

charged by Congress with the duty to enforce the civil rights

laws." Br. App. at 17. Merely to state the proposition is

sufficient to demonstrate its absurdity.

The Department may argue that it was really promoting civil

rights enforcement on the appeal by seeking to protect the rights

of white persons. See, e.q. . Br. App. at 19-20. But that

argument could be made by most parties who lose cases against

civil rights advocates. The losing parties in Shelley v.

Kraemer. supra. claimed that their constitutional rights were

being violated. 334 U.S. at 22. So did the defenders of

20

"state's rights" in countless civil rights battles of the 1960's.

Taken to its logical conclusion, the Department's position would

eviscerate §1988 because all opposition to desegregation could be

portrayed as advocacy of the constitutional rights of white

individuals.

Congress enacted §1988 because "the[] civil rights laws

depend heavily upon private enforcement, and fee awards have

proved an essential remedy if private citizens are to have a

meaningful opportunity to vindicate the important Congressional

policies which these laws contain." Sen. Rept. No. 94-1011,

supra. at 1. Private enforcement was especially necessary in

this case, because here it was the United States Department of

Justice which sought to frustrate enforcement of the civil rights

laws. There could not be a more appropriate case for an award of

attorneys' fees.

D.

The Department's argument that the award of fees in this

case violates sovereign immunity (Br. App. 21-23) is based

entirely on circular reasoning. The Equal Access to Justice Act,

28 U.S.C. §2412(b), waives sovereign immunity in any case where

the United States would be liable under 42 U.S.C. §1988. If the

Government does something which would make any other party liable

for fees under the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Act, 28 U.S.C.

§2412(b) makes the Government equally liable for fees.

21

The issue in this case is whether the prevailing parties on

the Justice Department's unsuccessful appeal are entitled to fees

under §1988. If so, §2412 (b) requires the United States to pay

the fees. If not, the United States need not pay the fees.

There is nd separate issue under §2412(b).

The Department's sovereign immunity argument, like its §1988

analysis, relies upon wildly out-of-context use of cases which

are thoroughly inapposite. Hall v. United States. 773 F.2d 703

(6th Cir. 1985) and the other cases cited in Br. App. at 22, were

not civil rights cases; they were federal actions brought under

an entirely separate body of law not governed by 42 U.S. §1988.

These cases stand for the simple proposition that §2412(b)

liability rests upon §1988 liability. Here the Government's

behavior — subjecting the other parties to two years of

appellate litigation in an effort to block enforcement of a civil

rights settlement — is the very sort of behavior for which fees

should be awarded under §1988. Accordingly, sovereign immunity

is waived under §2412(b).

E.

Finally, the Department complains that the fees awarded for

time spent on the fee application below were excessive. (Br.

App. at 2 0-21 n. 16) . We agree that in a normal case where the

fees inquiry concerns only the appropriate rate, the correct

number of hours to be compensated, apportionment between winning

22

and losing issues under Hensley v. Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424

(1983), etc., a fees application should take less time. But here

the Department argued that it was not liable for any fees at all,

advancing complex legal theories to support that claim. The

Department's brief on appeal suggests that it sees this case as a

test of its ability to obstruct civil rights enforcement without

incurring fees liability, and perhaps of the ability of other

intervenors to do likewise after this Administration has left

office. Under these circumstances, the number of hours spent by

the Richardson intervenors responding to the Department's

arguments are reasonable and should not be disallowed.

CONCLUSION

For the above-stated reasons, the order of the district

court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

RICHARD H. DINKINS

Williams & Dinkins

203 Second Avenue North

Nashville, TN 37201

[615] 244-3988

[Signatures continued on next page]

23

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JOEL BERGER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

[212] 219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFF/INTERVENORS-

APPELLEES RAYMOND RICHARDSON, JR.,

et al.

24

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that true and exact copies of the foregoing

Brief of Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees Raymond Richardson, Jr.,

et al., have been forwarded via first class mail, postage

prepaid, to William R. Yoemans, Esq., Appellate Section, Civil

Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

20530; Christine Modisher, Assistant Attorney General of the

State of Tennessee, 450 James Robertson Parkway, Nashville, TN

37219; John L. Norris, Esq., Hollins, Wagster and Yarbrough,

P.C., 8th Floor, Third National Bank Building, Nashville, TN

37219; Aleta G. Arthur, Esq., Gilbert, Frank and Milom, 13th

Floor, Third National Bank Building, Nashville, TN 37219; George

E. Barrett, Esq., P.O. Box 2846, 217 Second Avenue North,

Nashville, TN 37219; and Joe B. Brown, Esq., United States

Attorney, 879 U.S. Courthouse, Nashville, TN 37203, this 23rd day

of May, 1988.

aOEL BERGER /

Attorney for Plaintiff/Intervenors-

Appellees Raymond Richardson, Jr.,

et al.

ADDENDUM

united states court or appeals

for the sixth circuit

Cm* nn -88-5155

Cm* Caption:

United States of America v. Raymond Richardson, Jr., et al.

APPEII-aNT’S/APPELLEE’S DESIGNATION

OF .APPENDIX CONTENTS

. r r n .../ . n ^ h . p M «. Sink O k m. Rid. 11(b), b«.br * * > « « *• “ "*■ " *• di>̂ ' ‘

court’s ncord m iuan to ba include! in tha joint appandix

^<JOEL BERGER

NOTE; Appendix design**** to be included in brief*.

5CA-L08

7/87