Garner v. Louisiana Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garner v. Louisiana Brief Amicus Curiae, 1961. 2a04e2cd-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9116e185-4561-4d32-b26a-9d1b3796d565/garner-v-louisiana-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

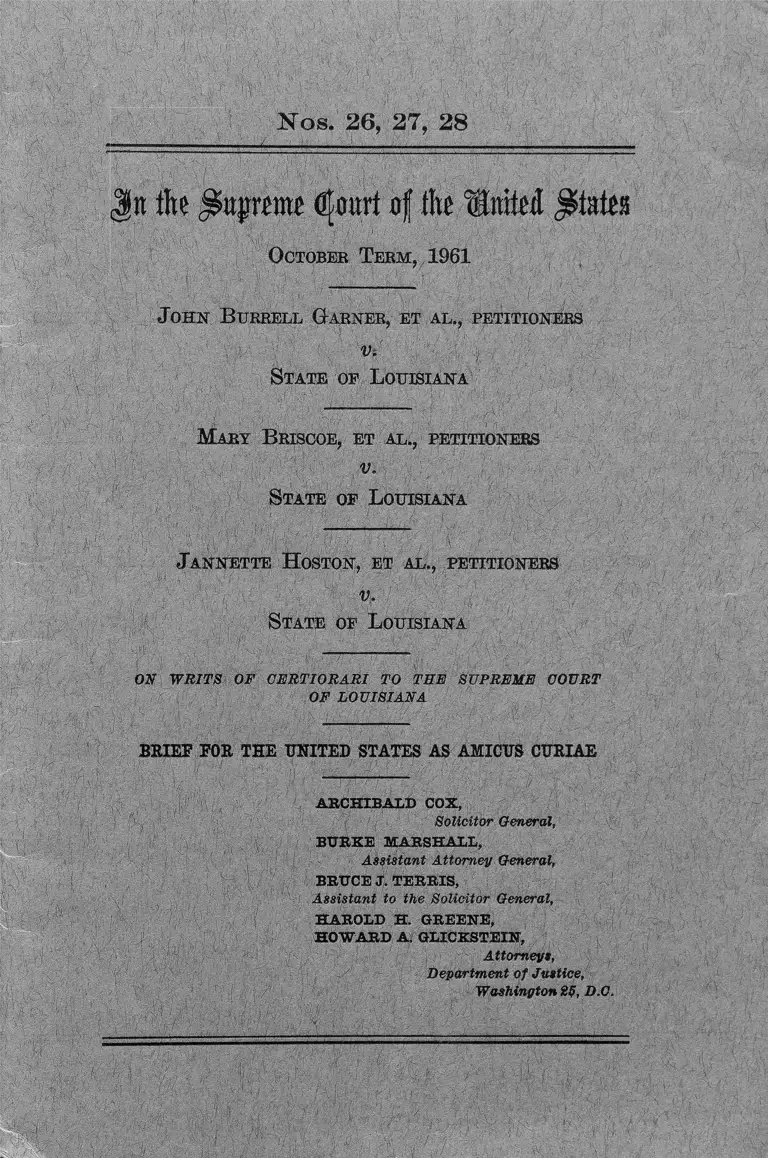

N o s . 26, 27, 28

October I jerm, 1961

J osh B urrell Garner, et al., petitioners

Vi

S tate op L ouisiana

Mary B riscoe, et al., petitioners

v.

S tate op Louisiana

J annette B oston, et al., petitioners

V,

S tate op L ouisiana

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO TEE SUPREME COURT

OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

ARCHIBALD COX,

Solicitor General,

BURKE M A R S H A L L ,

Assistant Attorney General,

BRUCE J. TERRIS,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

HAROLD H. GREENE,

HOWARD A. GLICKSTEIN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington 2$, D.C.

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below_____ ________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction______________

Questions presented_______

Interest of the United States------------ i------------------------ 3

Statement_________________________________________ 4

Summary of argument--------------------------------------------- 11

Argument_________________________________________ 16

I, The convictions violate the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment because there was no

evidence tending to prove essential elements of the

only offense charged and no charge of any offense

proved_____________________________________ 18

A. There was no evidence tending to prove that

petitioners violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7)

as charged in the informations__________ 18

1. Petitioners did not commit any acts of

the kind proscribed by L.S.A.-R.S.

14:103_________________________ 20

2. There was no evidence tending to prove

that petitioners acted “in such a

manner as would foreseeably disturb

or alarm the public”____________ 23

3. There was no evidence tending to prove

that petitioners’ conduct disturbed

or alarmed the public____________ 27

B. If the evidence tends to prove any offense, it

is an offense not charged. Conviction for

such an offense would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment__________________________ 30

II. The statute under which petitioners were convicted

is, if applied to petitioners, so vague and uncertain as

to violate due process_________________________ 33

A. Due process requires that a State statute give

fair notice of what conduct is criminal_____ 34

B. Section 103(7) did not give fair notice to

petitioners that their actions were illegal___ 35

607645—61 1 (I)

to

to

II

Argument—Continued Page

III. In the circumstances of these cases petitioners’ arrest

and conviction were the result of State, not privately,

imposed racial discrimination and therefore violate

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment_________________________________ 38

IV. In Briscoe v. Louisiana, petitioners’ arrest and convic

tion violated the Interstate Commerce Act_______ 46

A. The Interstate Commerce Act prohibits dis

crimination based on race in interstate bus

terminals____________________ 46

B. This contention can properly be considered by

this Court even though petitioners have not

presented i t ___________________________ 49

Conclusion________________________________________ 52

CITATIONS

Cases:

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S.

288_________________________________________ 50

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750______________ 48

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454_____________ 15, 47, 49

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715-------- ------------------------------------------------ 41,43,45.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568______ 37

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196________________ 13, 30, 33

Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385___ 34

International Harvester Co. v. Kentucky, 234 U.S. 216.. 37

Konigsberg v. State Bar, 353 U.S. 252______________ 18

Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451______________ 34

Light v. United States, 220 U.S. 523______________ 50

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501__________________ 16

Musser v. Utah, 333 U.S. 95_____________________ 34

Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373_______________ 34

Ohio Bell Telephone Go. v. Public Utilities Commission,

301 U.S. 292_________________________________ 26

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537__________________ 46

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476______ ________ _ 35

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232___ 18

Siler v. Louisville cfc Nashville R. Co., 213 U.S. 175__ 50

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147_________________ 36

State v. Christine, 239 La. 259____________________ 37

Ill

Cases—Continued Page

State v. Kraft, 214 La. 351_______________________ 37

State v. Martin, 199 La. 39___________________ 13, 31, 32

State v. Morgan, 204 La. 499_____________________ 33

State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961______ 11, 14, 20, 21, 26, 35, 37

Sunday Lake Iron Co. v. Wakefield, 247 U.S. 350____ 46

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199. --------- 18, 25

Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 823, 138 So. 851 _ 11, 20

United States v. C.I.O., 335 U.S. 106--------------------- 16, 50

United States v. Shaughnessy, 234 F. 2d 715__ _____ 26

United States ex rel. Vajtauer v. Commissioner of Immi

gration, 273 U.S. 103__________________________ 18

Wickard v. Filhurn, 317 U.S. I l l _________________ 48

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507________________34, 36

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356________________ 15, 45

Constitution and Statutes:

Constitution of the United States, Fourteenth Amend

ment___________________ 11, 14, 16, 17, 34, 38, 39, 44, 46

Interstate Commerce Act, Part II, Section 216(d), 49

U.S.C. 316(d)_________________________________ 46,47

Louisiana Act No. 227 of 1934___________________ 29

Louisiana Act No. 630 of 1960----------------------------- 38

La. Stats. Ann.—R.S. :

4: 5___________________________________ 39

4: 451-455____________ 39

13: 917_________________________________ 38

14: 63__________________________________ 31

14: 63.3 (1960 Supp.)______________________ 32

14: 103_ 11,12,13,20,23,26,27,28,30,33

14: 103.1 (1960 Supp.)_____________________ 22

14: 103(7)_______________________________ 5,6,8,

12, 13, 18, 20, 21, 22, 27, 28, 30, 33, 35, 36, 38, 44

15: 752_________________________________ 38

17: 10__________________________________ 39

33: 5066________________________________ 39

45: 522-525_____________________________ 38

45: 528-532_____________________________ 38

Miscellaneous:

McCormick, Evidence, §324 (1954)------------------------ 26

Note, 61 Col. L. Rev. 1103 (1961)------------------------- 46

Jn tfa jftqjrme Gjmtrt of ih Uniit& jjintes

Octobee Term, 1961

No. 26

J ohn B urrell Garner, et al., petitioners

v.

State op Louisiana

No. 27

Mart Briscoe, et al., petitioners

v.

State op L ouisiana

No. 28

J annette H oston, et al., petitioners

V .

State op Louisiana

ON W R IT S OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E SU PREM E COURT

OF L O U ISIA N A

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions of the Supreme Court of Louisiana in

Garner (G. 53x), Briscoe (B. 56), and Hoston (H.

55-56) and of the Nineteenth Judicial District Court

of Louisiana in each of these cases (G. 37; B. 38-39;

H. 38-39) are not officially reported.

1 The records in Garner v. Louisiana, No. 26, Briscoe v. Loui

siana, No. 27, and Hoston v. Louisiana, No. 28, are referred to

as “G.”, “B.”, and “H.”, respectively.

(l)

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Supreme Court, of Louisiana

in Garner was entered on October 5, 1960 (G-. 53), in

Briscoe, on October 5, 1960 (B. 56), and in Boston,

on October 5, 1960 (H. 55). The petitions for writs

of certiorari were granted on March 20, 1961 (365

U.S. 840; B. 56; B. 62; H. 58). The jurisdiction of

this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Petitioners, who are Negroes, were convicted by a

Louisiana state court of disturbance of the peace for

having sat at lunch counters reserved for whites.

The questions presented and discussed in this brief

are:

1. Whether petitioners’ convictions violated the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because

they are utterly unsupported by evidence proving

essential elements of the offense.

2. Whether the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment was violated by petitioners’ con

viction under a statute which, if applied to these

circumstances, is so vague and indefinite that it fails

to give fair notice of the conduct proscribed,

3. Whether, in the circumstances of this case, peti

tioners’ arrest and conviction violated the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because

the State was enforcing a government policy of racial

segregation.

4. Whether in. Briscoe v. Louisiana, No. 27, peti

tioners’ arrest and conviction deprived them of their

rights under the Interstate Commerce Act to service

3

on a non-discriminatory basis in a restaurant in a

bus terminal operated as part of interstate commerce.

Petitioners also raise additional questions which we

believe this Court need not reach (see infra, pp. 16-

17) and which we therefore have not discussed in this

brief:

1. Whether any arrest by state police and convic

tion by a State court of Negroes who enter and refuse

to leave private restaurants customarily open to all

members of the public except Negroes constitutes state

action violating the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether any arrest and conviction of Negroes

who enter and refuse to leave such restaurants de

prives them of their freedom of expression as pro

tected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

These cases involve racial discrimination and denial

of constitutional rights. While it is unnecessary here

to reach the constitutional problems common to the

so-called “sit-ins” generally, the convictions in these

cases arose in the context of a movement which is

significant through much of the country. Numerous

citizens have participated in this movement, and

many have been arrested and convicted by state

authorities in circumstances similar to those involved

in the cases now before the Court. The United

States is, of course, deeply concerned when many of its

citizens are arrested and convicted of crime without

due process of law and in a manner which denies to

them the equal protection of the laws, as guaranteed by

4

the Fourteenth Amendment. This concern is accentu

ated. when questions of widespread public interest and

significance are involved. Beyond that, the govern

ment believes that it may be able to assist the Court

by focusing upon issues which are dispositive without

involving broader and largely uncharted questions

concerning the meaning of “ State action.” I t is

because of these considerations that the United States

deems it appropriate to participate as amicus curiae.

STATEMENT

Garner v. Louisiana, No. 26.—On March 29, 1960,

petitioners, two Negro students at Southern Univer

sity, took seats at the lunch counter in Sitman’s Drug

Store, Baton Rouge, Louisiana (G. 30). One of the

petitioners ordered coffee but was advised by the pro

prietor of the drug store that he could not be served

(G. 30). Although Negroes may buy other goods in

the drug section of Sitman’s Drug Store at the same

counters as whites, there are no facilities for serving

food to Negro customers (G. 31-32). Within ten

minutes after petitioners had sat down at the counter

police officers arrived (G. 30). They were not called

by the owner of the store or any of his employees, and

the owner did not know who called the police (G. 30-

31). Instead, the arresting officers—Major Bauer

and Captain Weiner—were summoned by the police

officer on his “beat” near the store because he noticed

the two Negroes sitting at the lunch counter (G. 34).

The owner of the store received no complaints from

customers regarding the presence of the two Negroes

5

at the lunch counter (G. 33), and no other complaint

was made to the police department (G. 34-35).

When the police officers arrived at the drug store,

Major Bauer approached the students, told them that

they were violating the law, and asked them to leave

(G. 34). One of the students told the officers that he

had purchased an umbrella in the drug store and did

not understand why he could not sit at the lunch

counter (G. 34). When the students did not leave,

the police placed them under arrest, pursuant to

L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7), for having disturbed the peace,

and took them to police headquarters (G. 34-35).

Captain Weiner, one of the arresting officers, ex

plained the arrests at petitioners’ trial as follows

(G. 35) :

* * * the law says that this place was re

served for white people and only white people

can sit there and that was the reason they were

arrested.

* * * * *

The fact that they were sitting there and in

my opinion were disturbing the peace by their

mere presence of being there I think was a

violation of Act 103.

He similarly said that “ [t]he mere presence of these

negro defendants sitting at this cafe counter seat

reserved for white folks was violating the law * * *”

(G. 36).

Informations were filed against petitioners which

charged that they had violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7)

by refusing “ to move from a cafe counter seat at

607645— 61------2

6

Sitman’s Drug Store * * *, after having been ordered

to do so by the agent of Sitman’s Drug Store * * *”

(G. I) .2

After the trial, the trial judge rendered an oral

opinion in which he found petitioners guilty of having

violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7) and stated (G. 37):

* * * the evidence put on by the State [was]

that these two accused were in this place of

business * * * and they were seated at the

lunch counter in a bay where food was served

and they were not served while there, and

officers were called and after the officers ar

rived they informed these two accused that they

would have to leave, and they refused to leave.

* * * The Court is convinced beyond a reason

able doubt of the guilt of the accused from the

evidence produced by the State, for the reason

that in the opinion of the Court, the action

and conduct of these two defendants on this

occasion at that time and place was an act done

in a manner calculated to, and actually did,

unreasonably disturb and alarm the public.

* * *

Petitioners were convicted and sentenced to impris

onment for four months, three months of which would

be suspended upon the payment of a tine of $100.00

(G. 37-38, 41). Applications for writs of certiorari,

mandamus, and prohibition were filed in the Supreme

Court of Louisiana (G. 44-46), but the applications

were denied on the ground that the court was with

out jurisdiction to review the facts in criminal eases

2 The informations in all three cases identified each peti

tioner as “CM,” i.e., colored male, or “CF,” colored female

(G. 2; B. 2; H. 2).

7

and the rulings of the district judge on matters of

law were not erroneous (G. 53).

Briscoe v. Louisiana, No. 27.—On March 29, 1960,

petitioners, seven Negro students at Southern Univer

sity, took seats at the lunch counter at the restaurant

in the Baton Rouge Greyhound Bus Terminal (B. 30,

34). They attempted to order food but were told by

the waitress that “colored people are supposed to be

on the other side” and that the “seats where they

were seated are reserved for white people” (B. 30-

31). The waitress testified that she had no reason

for making these statements to petitioners other than

that they were Negroes (B. 31), and that petitioners,

besides ordering food, “hadn’t done anything other

than sit in those seats * * * reserved for whites”

(B. 32). The only posted sign read “Refuse service

to anyone” (B. 32). Negroes could be served in an

other part of the bus station in an area reserved for

them (B. 30-31, 32, 33-34).

A bus driver who was sitting at a booth near the

lunch counter telephoned the police “that there were

several colored people sitting at the lunch counter”

(B. 33, 34) .3 Captain Weiner, one of the arresting offi

cers, explained that the police “ were called because

of the fact that [petitioners] were sitting in a section

reserved for white people” (B. 35). After the police

asked petitioners to move and they had refused, pe

titioners were arrested for disturbing the peace (B.

3 A police officer testified that the desk sergeant was called by

“some woman at the Greyhound Bus Station” (B. 34). This

hearsay statement was apparently erroneous since the waitress at

the restaurant stated unequivocally that one of several bus

drivers in the restaurant called (B. 33).

8

35). Captain Weiner testified that petitioners were

arrested because “according to the law, in my opinion,

they were disturbing the peace.* * * The fact that

their presence was there in the section reserved for

white people, I felt that they were disturbing the

peace of the community” (B. 36). Captain Weiner

further emphasized that the basis of the charges

against petitioners that they were disturbing the

peace was “the mere presence of their being there”

(B. 38).

Informations were filed against petitioners which

charged that they had violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103

(7) by refusing “to move from a cafe coimter seat at

Greyhound Restaurant after having been ordered to

do so by the agent of Greyhound Restaurant * * *”

(B. 1). In his oral opinion, the trial judge found peti

tioners guilty of having violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103

(7), and stated (B. 38-39) :

* * * it is the decision of the Court that they

are guilty as charged for the reason that from

the evidence in this case their actions in sitting

on stools in this place of business when they

were requested to leave and they refused to

leave; the officers were called, the officers re

quested them to leave and they still refused to

leave, their actions in that regard in the opin

ion of the Court was an act on their part as

would unreasonably disturb and alarm the

public.

Petitioners received the same sentences as the peti

tioners in Garner (B. 43-44), and petitioners’ post

conviction applications in the Louisiana Supreme

Court were denied for the same reason as in the

Garner case (B. 46-49, 56).

9

Hoston v. Louisiana, No. 28.—On March 28, 1960,

petitioners, seven Negro students at Southern Univer

sity, took seats at the lunch counter at the S. H. Kress

Company store in Baton Rouge (H. 28-29). They

were not refused service or asked to move (H. 32-

33). Rather, they were simply not served and were

“advised” by a waitress that they could he served at

another counter in the Kress store where, “by cus

tom,” Negroes were served (H. 29, 32-34). Except

for the lunch counter, Negroes and whites may make

purchases in Kress at all counters (H. 31, 32). There

are no signs indicating that the lunch counters are

segregated hut petitioners were expected to have

known this “ [b]y custom and by noticing that the col

ored people were being served at the counter across

the store” (H. 32). Although the students did not

move, the manager took no immediate action hut con

tinued eating his lunch at the counter (II. 29-30).

After finishing his meal, he telephoned “ the police de

partment that [petitioners] were seated at the counter

reserved for whites” (H. 30). The manager testified

at petitioners’ trial that he called the police because

he “feared that some disturbance might occur” (H.

30). The manager also testified that the only conduct

of petitioners he considered to be a disturbance of

the peace was their presence at the lunch counter

(H. 33).

The police, after arriving at the store, asked peti

tioners to leave since “ they were disturbing the peace”

(H. 36). When petitioners refused, they were ar

rested, as one of the arresting officers testified, for

10

disturbing the peace “ [b]y sitting there” “because

that place was reserved for white people” (H. 37).

Informations were filed against petitioners which

charged that they had violated L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7)

by refusing “to move from a cafe counter seat at

Kress’ Store * * * after having been ordered to do

so by the agent of Kress’ Store * * *” (H. 1). The

trial judge, in his oral opinion, found (H. 39) :

* * * [petitioners] took seats at the lunch

counter which by custom had been reserved for

white people only. They were advised by an

employee of that store, or by the manager, that

they would be served over at the other counter

which was reserved for colored people. They

did not accept that invitation; they remained

seated at the counter which by custom had been

reserved for white people. * * * the action of

these accused on this occasion was a violation

of Louisiana Revised Statutes, Title 14, Section

103, Article 7, in that the act in itself, their

sitting there and refusing to leave when re

quested to, was an act which foreseeably could

alarm and disturb the public, and therefore was

a violation of the Statute that I have just

mentioned.

Petitioners were given the same sentences as the

petitioners in the Garner and Briscoe cases (H. 43-

44) and petitioners’ post-conviction applications to the

Louisiana Supreme Court were denied for the same

reasons as in those cases (H. 46-49, 55-56).

11

SUMMARY OP ARGUMENT

I

Petitioners’ convictions for disturbance of tbe peace

violate tbe due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment because there was no evidence tending to

prove essential elements of the only offense charged.

The informations did not charge the only offense

which even conceivably was proved.

A. Since there is no evidence tending to support the

convictions under L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103, the convictions

violate due process. Thompson v. City of Louisville,

362 U.S. 199. This statute requires proof of three

basic elements: (1) The accused must commit an act

of the kind proscribed; (2) the acts must be done “ in

such a manner as would foreseeably disturb or alarm

the public” ; and (3) there must be actual public alarm

or disturbance.

1. Petitioners clearly did not commit any acts of the

kind proscribed by Louisiana’s disturbance of the

peace statute. Earlier decisions of the Louisiana

Supreme Court make clear that disturbance of the

peace includes only violent, loud, or boisterous con

duct. Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 823,

138 So. 851 State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d

778. This construction is supported, and indeed

virtually compelled, by Section 103 itself, for all its

specific prohibitions involve such conduct. The rec

ords in these cases show that petitioners’ acts were

12

completely peaceful; they merely sat quietly at a

counter normally reserved for whites.

2. There is also no evidence tending to prove that

petitioners acted “in such a manner as would foresee-

ably disturb or alarm the public.” This requirement

is explicitly stated in Section 103 in its introductory

language applicable to all seven subdivisions. Peti

tioners, however, acted peacefully; the restaurant em

ployees merely refused to serve them and indicated

that petitioners were sitting at counters reserved for

whites. There was nothing in the reaction of these

employees or of customers or bystanders even sug

gesting that petitioners’ presence would cause a dis

turbance. And the police arrested petitioners, not

because of the likelihood of a disturbance, but for the

sole reason that they were sitting in the wrong place.

The only possible basis for the trial court’s findings

of a foreseeable disturbance is judicial notice, but

courts do not take judicial notice of debatable facts,

particularly when, as here, they are contradicted by

the evidence.

3. There is not the slightest evidence that peti

tioners’ conduct in fact disturbed or alarmed the

public. Subsection 7 of the statute, under which peti

tioners were convicted, is a loose, catch-all provision

prohibiting acts committed “in such a manner as to

unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.” Thus,

subsection 7 requires proof of actual alarm or dis

turbance caused by petitioners’ acts. Any other

interpretation would render this language redundant

with the requirement which applies to all of Sec

tion 103—that the conduct forseeably alarm or

13

disturb the public. And, furthermore, the history of

Section 103 strongly indicates that subsection 7 was

intended to be confined to actual disturbances.

B. I f the evidence in these cases proves any offense,

it is an offense which the informations did not charge.

The real thrust of the prosecutions—as both the infor

mations and oral opinions show—is an effort to

punish petitioners for criminal trespass. The Louisi

ana Supreme Court has held that Louisiana’s criminal

trespass law applies to persons who enter land law

fully, but refuse to leave when ordered to do so by

the proprietor. State v. Martin, 199 La. 39, 5 So. 2d

377. Here, however, there is no evidence that peti

tioners were asked to leave. But, in any event, peti

tioners were charged only with disturbing the peace,

not trespass. And this Court has held that it violates

due process to convict a defendant of a crime with

which he was not charged. Cole v. Arkansas, 333

The statute under which petitioners were convicted

is, if applied to petitioners, so vague and uncertain

as to violate due process.

Due process requires that a State statute give fair

notice of what conduct is criminal. This requirement

should be construed with particular strictness in a

case involving, at the least, the possibility that the

State is using the statute to promote racial discrim

ination. The Louisiana disturbance of the peace

statute—particularly as interpreted by the Louisiana

Supreme Court to apply only to non-peaeeful con-

607645— 61— 3

14

duct (State v. Sanford, supra)—does not give the

slightest indication that it applies to sitting quietly at

a lunch counter which is reserved for persons of an

other race where there is no disturbance nor reason to

foresee a disturbance. I f the statute applies to these

facts, it can be used to convict anyone for any conduct

that local officials, acting ad hoc, find distasteful.

I l l

Petitioners’ arrest and conviction were the result

of State, not privately, imposed racial discrimination

and therefore violate the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The State was not

merely allowing a private person to carry out private

discrimination on his own property or even enforcing

such discrimination. Acting through local police and

judicial authority, the State was imposing a policy

of its own.

A. The records show that petitioners were arrested

because of their mere presence at the lunch counters.

The police made the arrests not on the request of the

managers or employees of the lunch counters but

merely because petitioners were Negroes sitting in

areas normally reserved for whites.

B. Petitioners’ convictions were also based on their

race. The only grounds on which the trial court

could have found three essential elements of the of

fense are judicial notice or a ruling that the presence

or absence of these elements constituted a question of

law. Thus, the trial court must have determined that

public alarm or disturbance was foreseeable, that such

alarm or disturbance actually occurred, and that peti

15

tioners’ acts were unreasonable, by concluding that

those elements are automatically satisfied whenever

there is racial integration in public places.

C. This Court has made clear that, if a State statute

which is nondiscriminatory on its face is applied in a

discriminatory way, this constitutes a violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment, Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356. Such unconstitutional discrimination of

course occurs whenever enforcement of the law is

based on race. State action which promotes a State

policy of segregation and therefore violates rights

protected by the Constitution cannot be saved by using

the label “disturbance of the peace.”

IV

In Briscoe v. Louisiana, petitioners’ arrest and con

viction violated their rights under the Interstate

Commerce Act.

A. In Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454, 463-464,

the Court held that the Act forbids racial discrimina

tion against interstate passengers in restaurants oper

ated “ as an integral part of the bus carrier’s transpor

tation service for interstate passengers.” Although

petitioners were not interstate passengers, the Act for

bids interstate carriers to discriminate against “ any

particular person.” The record shows that the lunch

counter in Briscoe was located in the Greyhound Res

taurant in the Greyhound bus terminal. I t can fairly

be inferred, in the absence of any contrary evidence,

that the lunch counter is operated as an integral part

of interstate commerce.

16

B. Although petitioners have not presented this

issue either to this Court or the Louisiana courts, the

Court can properly consider it. If the Briscoe case

cannot be decided, contrary to our contentions, on the

basis of the same constitutional issue as the other

two instant cases, consideration of this statutory

issue would relieve the Court from considering further

constitutional questions. I t is of course a basic prin

ciple that the Court refuses to adjudicate constitu

tional issues unless such an adjudication is absolutely

necessary to the decision. The parties cannot minify

this principle simply by failing to raise the statutory

issue. See United States v. C.I.O., 335 U.S. 106, 110.

ARGUMENT

Petitioners, who are Negroes, were arrested by

state officers and convicted by State courts of having

disturbed the peace by entering and remaining at

lunch counters that are reserved for whites. Peti

tioners argue that (1) the State was enforcing a cus

tom of private racial discrimination in restaurants,

which constitutes state action in violation of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (see

Pet. Br. 18-24), and (2) the State was interfering

with freedom of expression in places open to the pub

lic in violation of the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment (cf. Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U.S. 501) (see Pet. Br. 36-38). These issues are of

great national importance, since if petitioners were

successful in either their two principal contentions,

this would probably be decisive of most of the numer

17

ous “sit-in” cases now pending in State courts (see,

e.g., Pet. in Garner, p. 28). Thus, resolution of these

issues might have important effect on the “sit-in”

movement which has reached considerable importance

virtually throughout the country. On the other hand,

these contentions raise broad and, we believe, difficult

constitutional problems.

In our view all of petitioners’ convictions are in

valid on three narrower grounds: (1) the State failed

to present any evidence whatsoever to support essen

tial elements of the offenses as defined by State law

in violation of the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment (see infra, pp. 18-33) ; (2) the

Louisiana statute under which petitioners were con

victed was so vague and uncertain, as applied to the

facts of these cases, as to violate the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (see infra,

pp. 33-38) ; and (3) the State, in these particular

cases, was itself imposing racial discrimination, not

merely enforcing a private landowner’s decision, in

violation of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment (see infra, pp. 38-46).4 Although

the issues raised by these propositions are constitu

tional, they are not only narrower but also, we

believe, more easily resolved than the other constitu

tional issues raised by petitioners. Accordingly we

do not discuss the broader questions.

4 In addition, we believe that the convictions in Briscoe are

invalid because they violate the Interstate Commerce Act (see

infra, pp. 46-51).

18

I

THE CONVICTIONS VIOLATE THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT BECAUSE THERE

WAS NO EVIDENCE TENDING TO PROVE ESSENTIAL ELE

MENTS OF THE ONLY OFFENSE CHARGED AND NO

CHARGE OF ANY OFFENSE PROVED

A. TH ER E WAS NO EVIDENCE TEN D IN G TO PROVE T H A T PETITIO N ERS

VIOLATED L .S .A .-R .S . 1 4 : 1 0 3 ( 7 ) AS CHARGED IN T H E IN FO R

MATIONS.

In Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199,

204, 206, this Court held that a conviction in a

State court must be set aside under the Fourteenth

Amendment “ if there is no support for these convic

tions,” or “ [t]he record is entirely lacking in evidence

to support any of the charges,” or is “without evi

dence of his guilt.” Cf. Konigsberg v. State Bar, 353

U.S. 252; Schivare v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353

IT.S. 232; United States ex rel. Vajtauer v. Commis

sioner of Immigration, 273 U.S. 103, 106. The deci

sion does not mean that a federal court may reverse a

State conviction merely because, upon re-evaluating

the record, it finds that the evidence is insufficient to

support the conviction. The conviction violates due

process, however, if there is no evidence at all tend

ing to prove one or more of the essential elements

of the offense.

The arrest, arraignment, and conviction of each

of the petitioners were specifically based upon sub

section 7 of the Louisiana statute punishing dis

turbance of the peace. L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7). The

statute provides:

Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of

the following in such a manner as would fore-

seeably disturb or alarm the public:

19

(1) Engaging in a fistic encounter; or

(2) Using of any unnecessarily loud, offen

sive, or insulting language; or

(3) Appearing in an intoxicated condition;

or

(4) Engaging in any act in a violent and

tumultuous manner by any three or more per

sons; or

(5) Holding of an unlawful assembly; or

(6) Interruption of any lawful assembly of

people; or

(7) Commission of any other act in such a

manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm

the public.

To support a conviction under this statute there must,

as we shall show below, be proof of three basic ele

ments of the offense:

(1) The accused must commit an act of the

kind proscribed by the statute;

(2) The acts must be done “in such a manner

as would foreseeably disturb or alarm the

public” ;

(3) If the charge is under subdivision

7, there must be actual public alarm or

disturbance.

The cases come here upon the evidence taken and

the findings made in the trial court, for the Supreme

Court of Louisiana refused to review the evidence

upon the ground that it was “ without jurisdiction to

review facts in criminal cases” (Gr. 53; B. 56; H. 56).

In none of the three cases was there any evidence to

prove any of the three indispensible elements of the

offense defined by the statute. In some instances the

trial court did not even make a finding upon an essen

20

tial element. Therefore, the convictions should be

set aside upon the authority of Thompson v. City of

Louisville.

1. Petitioners did not commit any acts of the kind

proscribed by L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103

L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103 proscribes six specific acts

which constitute a breach of the peace when done in

a manner which would foreseeably disturb or alarm

the public. Subsection 7 then forbids “ [commission

of any other act in such a manner as to unreasonably

disturb or alarm the public.” Admittedly, petitioners

engaged in none of the conduct described in the first

six subsections. They were charged specifically with

violation of subsection 7, an earlier version of

which the Supreme Court of Louisiana aptly described

as “ the general portion of the statute which does not

define the ‘conduct or acts’ the members of the Legis

lature had in mind” (State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961,

967, 14 So. 2d 778).

The State decisions giving content to the general

words make it plain that subsection 7 does not

embrace peaceful conduct such as that of peti

tioners. In Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La.

823, 138 So. 851, the Louisiana Supreme Court held

under an ordinance simply prohibiting disturbance of

peace that a disturbance of the peace is “any act or

conduct of a person which molests the inhabitants in

the enjoyment of that peace and quiet to which they

are entitled, or which throws into confusion things set

tled, or which causes excitement, unrest, disquietude,

or fear among persons of ordinary normal tempera

21

ment.” (173 La. at 828). A challenge to rooted cus

toms may cause intellectual unrest or emotional

excitement, but it is plain that the court’s definition

of a breach of the peace uses these words to encom

pass only conduct which is violent, loud, or boister

ous, or which is provocative in the sense that it

induces a physical disturbance such as fighting, riot

or tumult, or which arouses the fear of these dis

turbances among persons of normal temperament. A

later decision makes this plain. In State v. Sanford,

203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d 778, the evidence showed that

thirty Jehovah’s Witnesses approached a Louisiana

town for the purpose of distributing religious tracts

and persuading the public to make contributions to

their cause. The Witnesses were warned by the

Mayor and police officers that “ their presence and

activities would cause trouble among the population

and asked them to stay away from the town

* * *” (203 La at 964). The trial court found

that the Witnesses entering the town and stopping

passers-by in the crowded main street under these

circumstances “ might or would tend to incite rioting

and disorderly conduct” {id. at 965). The Supreme

Court of Louisiana set aside convictions for breach

of the peace, thus holding in effect that the defend

ants were not pursuing a “disorderly course of

conduct which would tend to disturb the peace.” Al

though the language of the statute was subsequently

altered, there is nothing in the change or in subse

quent court decisions to throw doubt upon this ruling.

Indeed, the conclusion that L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7)

does not reach peaceful and orderly conduct is virtu-

607645— 61------ 4

22

ally compelled by reading the statute as a whole. The

first six subsections deal with violence or loud

boisterous conduct. The only possible exceptions

are (i) the use of insulting language, which in this

context plainly refers to insults calculated to provoke

violence, and (ii) the holding of an unlawful as

sembly, which is also likely to result in the outbreak

of violence. The catch-all language in subsection 7

would normally be interpreted in the light of the pre

ceding subsections as an effort to cover other forms

of violence or loud and boisterous conduct not already

listed.

I t is also apparent that the Louisiana legislature

doubted whether L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7) covered peti

tioners’ acts. Immediately after the events for which

petitioners are being prosecuted, the legislature re

wrote the statute and added a definition of acts which

may cover the present case (L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103.1

(1960 Supp.)) :

A. Whoever with intent to provoke a breach

of the peace, or under circumstances such that

a breach of the peace may be occasioned

thereby:

* * * * *

(4) refuses to leave the premises of another

when requested so to do by any owner, lessee,

or any employee thereof, shall be guilty of

disturbing the peace.

The contrast between this language and the statute

under which petitioners were accused confirms the

interpretation flowing from the judicial precedents

and the natural meaning of the words.

23

In these cases, there can be no doubt that petition

ers’ acts were peaceful. They merely sat down

quietly at counters reserved for whites. Such conduct

is clearly not of the kind proscribed in Lousiana as

disturbance of the peace.

2. There was no evidence tending to prove that peti

tioners acted “in such a manner as would foresee-

ably disturb or alarm the public”

Even if petitioners committed acts of the kind em

braced by the statute, they could not be convicted with

out proof that the acts were done, “in such a manner

as would foreseeably disturb or alarm the public.”

L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103 sets out this element of the offense

in the introductory language applicable to all seven

divisions.

Although the trial court found that petitioners’

conduct was calculated to alarm and disturb the pub

lic (G*. 37; B. 39; H. 39), there was an absolute lack

of evidence to support the finding. Petitioners sat

down quietly at a lunch counter normally reserved for

whites. In Garner they were told that they could not

be served because they were Negroes, but they were

not even asked to move. They remained there quietly

until ten minutes later when the police arrested them

(Gr. 30-32). In Briscoe, the waitress told them that

“colored people are supposed to be on the other side,”

and declined to serve them (B. 30-31). They re

mained quietly in their seats until they were arrested

upon the arrival of the police. In Host on they were

told by the waitress that they could be served at an

other counter. They were not asked to leave and

24

stayed where they were until once again the police

made the arrests (H. 29, 32-34). There was nothing

in this conduct, which could conceivably “disturb or

alarm the public.”

Admittedly, petitioners did not engage in violence

or any other loud or tumultuous conduct. There is

nothing in sitting quietly at a lunch counter, even

though one knows that he may not be welcome, which

can be said by its very nature to give him warning

of public alarm. Petitioners made no speeches. They

did not even speak to anyone except to order food.

They carried no placards, and did nothing, beyond

their presence, to attract attention to themselves or

others.

There is nothing in the reaction of the manager or

waitresses or in the conduct of customers or bystand

ers to suggest that petitioners’ presence would cause

a public disturbance. Negroes were welcome in all

three establishments. The arresting officers testified

that petitioners’ sole offense was that they, being

Negroes, sat in a section reserved for whites ((4. 35-

36; B. 35-36; H. 37). In the Garner ease neither the

owner of the drug store nor any bystanders thought it

necessary to call the police. The arrests were made

because a policeman near the store saw that Negroes

were sitting at the white lunch counter. (Gk 30-31,

34). He gave no testimony of an actual disturbance

nor did he say that there was a reason for fearing a

breach of the peace. In Briscoe, the waitress testi

fied that petitioners “ hadn’t done anything other than

sit in these seats * * * reserved for whites” (B. 32).

In Hoston the manager did testify that he “ feared

25

that some disturbance might occur” (H. 30), but he

was so little concerned that he continued to sit at the

same lunch counter eating his lunch and waited until

he was finished to call the police. The manager also

acknowledged that the only conduct which he con

sidered disturbing was the petitioners’ mere presence

at the counter (H. 29-30, 33). He gave no reasons for

his concern and did not say what he meant by a “ dis

turbance. ” Under these circumstances, the manager’s

general statement gives “ no support” for the convic

tions, within the meaning of Thompson v. City of

Louisville, supra (see 362 U.S. at 204).

The police gave no evidence that a public disturb

ance was to be anticipated. In Garner, Captain

Weiner, one of the arresting officers, explained that

he made the arrests because “the law says that this

place was reserved for white people” (G-. 35). In

Briscoe, Captain Weiner said that, “The fact their

presence was there in the section reserved for white

people, I felt that they were disturbing the peace of

the community” (B. 36). Captain Weiner’s testimony

in Boston was substantially the same (see H. 36-37).

Not a single police officer said a word which even

remotely implies that fighting, loud words, or any

other disorder seemed likely to occur.

I t may be argued that the finding that disturbances

were a foreseeable result of the mere presence of

Negroes at the lunch counter was based on judicial

notice derived from general knowledge of the com

munity—perhaps coupled, as the State suggests, with

newspaper stories which are not in the record (Brief

in Opp., pp. 11-12). But courts can take judicial

26

notice, especially in criminal cases, only of obvious

and incontrovertible facts. Ohio Bell Telephone Go.

v. Public Utilities Commission, 301 U.S. 292, 301;

United States v. Shaughnessy, 234 F. 2d 715, 718

(C.A. 2); McCormick, Evidence, §324 (1954). Cer

tainly, it is neither obvious nor incontrovertible, in

the present day, that a disturbance may occur merely

because Negroes sit peacefully at a lunch counter

theretofore reserved for whites. All the facts pre

sented in these cases indicated that no disturbance

would occur. The constitutional requirement that a

State introduce some evidence of each of the essential

elements of a criminal offense before conviction can

not be cast aside through judicial assumptions which

are dubious at best and are also contradicted by the

evidence in the record.

Of course, it is plain that petitioners’ conduct was

likely to disturb the sensibilities of those members of

the public who hoped for the preservation of racial

segregation in restaurants and at lunch counters.

I t would arouse resentment among the prejudiced.

But the decision in State v. Sanford, supra (203 La.

961, 14 So. 2d 778), makes it clear that L.S.A.-R.S.

14:103 does not reach conduct which merely disturbs

or alarms members of the public in this sense of the

words.

As stated above, the Jehovah’s Witnesses whose

convictions were reversed in State v. Sanford had been

warned by the Mayor and police officers that “their

presence and activities would cause trouble among the

population and asked * * * to stay away from the

town * * *” (203 La. at 964); and the trial court

27

found that the Witnesses entering the town and

stopping passersby in the crowded main street under

these circumstances “ might or would tend to incite

rioting and disorderly conduct” (id. at 965). The

Supreme Court of Louisiana held that, as a matter of

law, this was not “ disorderly course of conduct which

would tend to disturb the peace.” (id. at 970).

3. There was no evidence tending to prove that peti

tioners’ conduct disturbed or alarmed the public

In the Briscoe and Boston cases there was neither

evidence nor a finding that petitioners had caused a

disturbance. In the Garner case the trial court made

such a finding (G-. 37), but there is not a scintilla of

evidence to support it. There was no fighting, no

pushing or shoving, no argument nor even loud talk;

there were no speeches nor the congregation of an un

usual number of people. I t was not even shown that

the presence of petitioners attracted public attention.

If, as we believe, the actual disturbance of some part

of the public is a third essential element of the offense

defined by L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103(7), then the con

victions must be invalidated for an absolute lack of

evidence.

Under the first six subsections of L.S.A.-R.S.

14:103, which proscribe specific acts, proof of an actual

disturbance is not required. The seventh subsection

is a loose catch-all of undefined conduct except as

limited by implication, and it would therefore be

natural to confine its generality by adding other

indicia of misconduct. The language alone is enough

to show that this was done by adding the requirement

28

that the “acts/’ whatever they might be, be done “in

such a manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm

the public.” The rest of L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103 shows

that these words refer, not to tendency of the acts, but

to their actual consequences.

Thus the opening sentence provides that “ [d isturb

ing the peace is the doing of any of the following in

such a manner as would foreseeably disturb or alarm

the public * * *” (emphasis added). I f subsection 7

is construed to cover any act likely to disturb or

alarm, it simply repeats the opening sentence. I t

would certainly be unusual, to say the least, for the

legislature to write a statute which prohibits acts

which probably will disturb or alarm the public when

done “in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb

or alarm the public * * If this were the intent,

the redundancy could easily have been avoided by

stating that “ [disturbing the peace is the doing of

any act in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb

or alarm the public including * * and then setting

out the first six subsections of Section 103. The addi

tion of subsection 7 shows that actually causing dis

turbance or alarm was intended to be an element of

the crime.

Our construction is reinforced by the history of

Louisiana’s legislation punishing disturbance of the

peace. Prior to 1942, the statute specifically pro

hibited only loud or obscene language, exposing one’s

person, or using a deadly weapon in a public place,

and then provided in a catch-all section that “any per

son * * * who shall do any other act, in a manner cal

culated to disturb or alarm the inhabitants * * * or

29

persons present” would be guilty of a misdemeanor,

Act No. 227 of 1934. In 1942, the statute was changed

to its present form, which eliminates the last two spe

cific prohibitions mentioned above but adds five other

specific prohibitions. Further, the present act re

quires proof that even acts within the specific prohibi

tions will foreseeably disturb or alarm the public—a

requirement which the 1934 act applied only to the

catch-all provision. The language in the catch-all

provision itself has been significantly changed from

prohibiting “ any other act, in a manner calcu

lated to disturb or alarm the inhabitants * * *” to

prohibiting “ [commission of any other act in such a

manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm the

public.” I t thus appears that the Louisiana legisla

ture in 1942 decided to spell out in more specific pro

hibitions acts which were previously covered in the

catch-all provision. Having specifically prohibited

the disturbances of the peace with which it was

primarily concerned, the catch-all provision was

limited, probably for the reason suggested above, so

as to cover only actual disturbances.

Moreover, immediately after the events involved in

these eases, the Louisiana legislature passed a disturb

ance of the peace statute which has significantly

different language than the statute involved in this

case. That statute (quoted supra, p. 22) clearly

requires proof that a disturbance was at most foresee

able or likely. The language used in Section 103 is

in marked contrast.

30

Barring any inferences which, can be drawn from

the decision below, there are no Louisiana cases upon

this question. The decision below gives no guidance

because there is no opinion, and the court refused to

examine the evidence (GK 53; B. 56; H. 56). Under

these circumstances this Court should adopt the inter

pretation which is supported by analysis of the lan

guage and history of act and hold that a conviction

under subsection 7 requires actual alarm or dis

turbance. Since there was no evidence of this ele

ment of the crime, it furnishes an additional reason

for voiding the convictions.

B. IF T H E EVIDENCE TENDS TO PROVE A N Y O FFENSE, IT IS AN

OFFENSE NOT CHARGED. CONVICTION FOR SUCH A N OFFENSE

WOULD VIOLATE T H E FO U RTEEN TH A M EN D M EN T

It seems apparent that the real thrust of the pros

ecutions was an effort to convict petitioners of crim

inal trespass, or perhaps to punish them for seeking,

in violation of State pol icy, to eat at lunch counters

previously reserved for whites. To impose sentence

upon either ground when the information alleged

disturbing the peace would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment as a conviction upon a charge not made.

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U.S. 196. To stretch L.S.A.-

R.S. 14:103, which proscribes breach of the peace, so

as to cover either of these offenses, even if proper as

a matter of State law, is to render it void under the

federal Constitution as a vague and indefinite crim

inal statute which gives no notice of the offense. See

Point II, pp. 33-38, infra. And of course, a conviction

31

for violating a State-imposed policy of segregation in

public restaurants would be invalid as a denial of

equal protection of the law. See Point III, pp. 38-

46), infra.

The record contains some elements of a criminal

trespass under many State laws, but it seems doubt

ful whether the Louisiana trespass statute is appli

cable. The closest provision was L.S.A.-R.S. 14: 63

which prohibits “ [t]he unauthorized and intentional

entry upon any: (a) enclosed and posted plot of

ground; or * * * (e) structure * * *.” In these

cases, however, petitioners ’ initial entry into the struc

ture was authorized since the business invited the

trade of Negroes and therefore authorized them to

enter. While petitioners were not authorized to enter

the portions of the structure reserved for whites, the

statute apparently prohibits entry into a portion of a

structure only if it is enclosed and posted. None of

the lunch counters involved in these cases was en

closed and posted. I t does not help the State’s case

to point out that, despite its language, the Louisiana

Supreme Court has held that the statute applies to

persons who enter land lawfully, but refuse to leave

when ordered to do so by the proprietor. State v.

Martin, 199 La. 39, 5 So. 2d 377 (1941). In the

Garner and Most on cases, the owner did not ask peti

tioners to leave the premises or even to move from

the counter (Gr. 30-33; H. 32-33). In the Briscoe

case, petitioners were merely told by a waitress that

they were seated at a counter reserved for whites

and would have to go to another counter to be served

32

(B. 30-33).3 In this case, unlike Stale v. Martin,

there was no evidence that the proprietor or his agent

unequivocally requested any petitioner to leave the

premises.5 6

5 In all three cases, the informations alleged that peti

tioners refused to leave after being ordered to do so by an

agent of the owner (G. 1; B. 1; IX. 1). As to the findings,

the trial court stated in Garner only that the police asked

petitioners to leave just before they were arrested (G. 37); in

Briscoe that they were asked to leave (by whom is not

stated) before the police arrived (B. 38-39) ; in Hoston that

an employee of the store or the manager advised them “that

they would be served over at the other counter” and that they

refused to leave when requested (H. 39).

The evidence at trial, liow'ever, shows in Gamer that

petitioners were advised that they could not be served, but

they were never asked by the proprietor or any employee to

leave (G. 30); in Briscoe, although the prosecutor’s leading

questions assume that petitioners were asked to move (B. 31),

the witness’s testimony directly on this subject was that peti

tioners were told only that “colored people are supposed to be

on the other side” and that the “seats where they were seated

are reserved for white people” (B. 30-31); and in Hoston

the petitioners were not served and were “advised” by a wait

ress that they could be served at another counter (PI. 29, 32-

33, 34), but the testimony is explicit that they were never

refused service or asked to move (H. 32-33).

6 Apparently the Louisiana legislature believed that the crim

inal trespass statute in force during these events did not cover

“sit-ins.” In 1960 the legislature passed a new criminal tres

pass statute which reads (L.S.A.-B..S. 14:63.3 (1960 Supp.)):

“No person shall without authority of law go into or upon

or remain in or upon any structure * * * which belongs to an

other * * * after having been forbidden to do so * * * by any

owner, lessee, or custodian of the property or by any other

authorized person. * * *”

This measure was enacted and approved by the Governor, as

an emergency measure on June 22, 1960, immediately subse

quent to the incidents involved in these cases.

33

We refer to the criminal trespass statute chiefly

to suggest some explanation of why the prosecutor

attempted, without evidence, to convict petitioners

of disturbing the peace. As a matter of law it

is immaterial whether the evidence made out a crim

inal trespass. Petitioners were charged specifically

with disturbing the peace in violation of L.S.A.-

R.S. 14:103(7). Under the law of Louisiana and

the United States Constitution, therefore, petitioners

could not be lawfully convicted of some different

offense. State v. Morgan, 204 La. 499, 15 So. 2d

866 (1943); Cole v. Arkansas, supra. Moreover, dis

turbing the peace was the only issue at trial. As this

Court held in Cole v. Arkansas (333 U.S. at 201),

“ I t is as much a violation of due process to send

an accused to prison following conviction of a charge

on which he was never tried as it would be to

convict him upon a charge that was never made.”

I I

THE STATUTE UNDER W H ICH PETITIONERS WERE CON

VICTED IS, IE APPLIED TO PETITIONERS, SO VAGUE AND

UNCERTAIN AS TO VIOLATE DUE PROCESS

Since the Louisiana courts have final authority to

interpret State legislation, it might have been permis

sible, as a matter of State law, for Louisiana to disre

gard the language of L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103 and its own

prior decisions and reinterpret the statute to punish

petitioners’ peaceful conduct. If that be the signifi

cance of the decision below, there may be evidence to

support the judgments, but the convictions fall upon

another constitutional ground—the statute becomes

so vague and indefinite that its enforcement denies

34

due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

A. DUE PROCESS REQUIRES T H A T A STATE STATUTE GIVE PA IR

NOTICE OE W H A T CONDUCT IS C R IM IN A L

This Court has repeatedly held that a State statute

violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment if it fails (i) to give fair notice of what

acts it encompasses and (ii) to provide the trier with

a sufficiently definite standard of guilt to avoid con

viction on an ad hoc basis.7 8 E.g., Lanzetta v. New

Jersey, 306 U.S. 451; Connolly v. General Construc

tion C o 269 U.S. 385; Musser v. Utah, 333 U.S. 95,

97; Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507, 519. As this

Court observed in Connolly (269 U.S. at 391):

* * * a statute which either forbids or requires

the doing of an act in terms so vague that men

of common intelligence must necessarily guess

at its meaning and differ as to its application,

violates the first essential of due process of law.

Similarly, in Lanzetta, the Court defined the fair

notice required by due process as (306 U.S. at 453) :

* * * Uo one may be required at peril of

life, liberty or property to speculate as to the

meaning of penal statutes. All are entitled to

be informed as to what the state commands or

forbids. * * * s

7 I t is possible that the requirement of clarity with respect

to fair notice to defendants is not exactly equivalent to the

requirement with respect to guidance for the State courts, be

cause it may be assumed that the State judges are more com

petent to interpret a statute than are prospective defendants.

8 Nash v. United States, 229 U.S. 373, is not to the contrary.

There, Mr. Justice Holmes said that “* * * the law is full of

instances where a man’s fate depends on his estimating rightly,

35

Thus, when a statute gives a defendant insufficient

notice of the conduct prohibited, his conviction is

invalid.

B. SECTION 1 0 3 ( 7 ) DID NOT GIVE FAIR NOTICE TO PETITIONERS

TH A T T H E IR ACTIONS WERE ILLEGAL

Section 103(7) has on its face several ambiguities.

I t is not entirely clear whether the prosecution must

show an actual disturbance of the peace or only that

such a disturbance is foreseeable (see supra, pp.

27-28); or whether subsection 103(7) prohibits un

reasonable acts which cause a disturbance of the peace

or acts which cause the public to act unreasonably.

Furthermore, the meaning of “ unreasonably” is not

defined. Despite these difficulties, we assume argu

endo that the statute is constitutional if it is con

strued as we have suggested, i.e., if it applies only to

the acts specifically listed and other similar violent,

loud, or boisterous conduct of the kind generally

known to disturb the public order. I t was only upon

this reading that the Louisiana Supreme Court sus

tained the constitutionality of earlier but similar

legislation. State v. Sanford, supra, 203 La. 961, 14

So. 2d 778.

The instant cases, however, do not involve an ordi

nary disturbance of the peace. First, all three cases

involve racial discrimination. In our view, the facts

that is, as the jury subsequently estimates it, some matter of

degree” (id. at 377). But this statement only illuminates the

undisputed fact that “ ‘the Constitution does not require impos

sible standards’; all that is required is that the language ‘con

veys sufficiently definite warning as to the proscribed conduct

when measured by common understanding and practices

* * * ” Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, 491.

36

clearly show that the State was itself promoting its

own policy of racial discrimination (see infra, pp.

38-46), but even if this contention is not accepted,

petitioners’ arrest and conviction at the least have the

effect of promoting private racial discrimination. In

such circumstances, we submit that this Court should

apply a strict standard in determining whether a

statute is unconstitutionally vague. For a vague

statute provides all too easy means by which a State

can impose ad hoc criminal penalties in order to pro

mote racial discrimination. Winters v. New York,

333 U.S. 507, 509-510, 517, indicates that the degree

of certainty required for due process is particularly

strict in the delicate area of freedom of expression;

otherwise, the Court said, expression which is con

stitutionally protected would be effectively prohibited

by the very vagueness of the law. See also Smith v.

California, 361 U.S. 147, 151.. Similar considerations

call for a strict standard of constitutional certainty in

any statute applied to support racial discrimination.

Second, there is not a word in L.S.A.-R.S. 14:103

which suggests that it prohibits sitting quietly at a

lunch counter, in a store into which one has been

invited by the proprietor, and asking for service

despite the proprietor’s previous policy of racial

segregation. Nor is there any warning that staying

there peacefully after service has been refused be

comes criminal. Petitioners’ conduct caused no dis

turbance ; there was no reason to foresee a disturbance.

I f the statute applies to these facts, it can be used

to convict anyone for any conduct that the local

officials, acting ad hoc, find distasteful.

37

Interpretation of a State statute prior to the de

fendant’s conduct may sometimes clarify otherwise

indefinite language sufficiently to satisfy the require

ments of fair notice. See e.g., Chaplinsky v. New

Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 574; International Harvester

Go. v. Kentucky, 234 U.S. 216. Here, however, the

latest decision of the Louisiana Supreme Court on this

subject interpreted the predecessor disturbance-of-the-

peace statute (one which, unlike the statute involved

in this case, clearly did not require proof of an

actual disturbance (see supra, pp. 28-29)) so as not

to apply to peaceful activities. State v. Sanford,

supra. The Louisiana court interpreted the statute in

this manner partially because (203 La. at 970) :

* * * to construe and apply the statute in the

way the district judge did would seriously in

volve its validity under our State Constitution,

because it is well-settled that no act or conduct

however reprehensible, is a crime in Louisiana,

unless it is defined and made a crime clearly

and unmistakably by statute.9 * * *

9 The Louisiana Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that

under its own constitution fair notice is an element of due

process. See, e.g., State v. Christine, 239 La. 259, 118 So. 2d

403 (1960) ; State v. Sanford, supra; State v. K raft, 214 La.

351, 37 So. 2d 815 (1948). In State v. K raft, supra, the court

explained the requirement of certainty (214 La. at 356) :

“* * * i t is sufficient to say that a criminal statute, in order

to he valid and enforceable, must define the offense so specifi

cally or accurately that any reader having ordinary intelligence

will know when or whether his conduct is on the one side or the

other side of the border line between that which is and

that which is not denounced as an offense against the law.”

38

The per curiam decisions of the Louisiana Supreme

Court in the instant cases are directly contrary to the

Sanford case since here the court applied Section 103

to completely peaceful activity. Thus, petitioners

were not given fair notice that their conduct was

criminal either by the terms of the statute or by its

interpretation in the Louisiana courts.

I l l

UN-DEE THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THESE CASES, PETITIONEES ’

ARREST AND CONVICTION WERE THE RESULT OF STATE,

NOT PRIVATELY, IMPOSED RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AND

THEREFORE VIOLATE THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE OF

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

As we have shown above (pp. 18-33), the records in

these cases are devoid of evidence which could sustain

a conviction for disturbing the peace. But despite

this lack of evidence of any violation of L.S.A.-R.S.

14:103(7), petitioners were arrested and convicted.

Under the circumstances of these cases, it seems plain

that the arrests and convictions were simply attempts

to effectuate a State policy of racial segregation

which violates the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.10

10 The Louisiana State policy of racial segregation is indicated

by a multitude of legislation. In 1960, the legislature passed

a joint resolution which began (Act No. 630 of 1960):

“Whereas, Louisiana has always maintained a policy of segre

gation of the races, and

“Whereas, it is the intention of the citizens of this sovereign

state that such a policy be continued. * * *”

There are statutes in Louisiana which require segregated

seating on trains (L.S.A.-R.S. 45:528-632), and in railroad

waiting rooms (L.S.A.-R.S. 45:522-525); which specify that

court dockets shall reflect the race of the parties in divorce

cases (L.S.A.-R.S. 13:917); which compel segregation in penal

39

In contending that petitioners’ arrest and convic

tion were a denial of equal protection of the law,

we do not rely on the obvious fact that since peti

tioners were considered both by the restaurants and

the police to be sitting in the wrong place merely

because they were Negroes, their arrest and convic

tion depended on their race. While petitioners argue

that this enforcement of local custom constitutes racial

discrimination enforced by State action within the

meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, (Pet. Br.

18-24), we do not consider it necessary to reach this

“broad” contention (see supra, pp. 16-17). For here

petitioners’ arrest and conviction were the result

of the State’s own policy of racial discrimination

even though it happened to be combined with pri

vately imposed discrimination. The State was not

merely allowing a private person to carry out private

discrimination on his own property or even enforcing

such discrimination. Acting through local police and

judicial authority, it imposed a policy of its own.

A. The records show that petitioners were arrested

because of their “mere presence” at the lunch coun

ters. The police officers acted, not to curb a disturb

ance of the peace but to carry out what they

institutions (L.S.A.-R.S. 15:752); which prohibit persons of

one race from establishing residence within a “community”

of the other race without approval of a majority of the

residents of the other race (L.S.A.-R.S. 33:5066); which re

quire segregated box offices for circuses (L.S.A.-R.S. 4:5) and

which prohibit the arrangement of dances, athletic contests,

etc., where Negroes and whites will be present together

(L.S.A.-R.S. 4:451-455). Even the blind are segregated under

Louisiana law (L.S.A.-R.S. 17:10). In these very cases each

petitioners’ race was indicated on the information (see supra,

p. 6, note 2).

40

considered to be the State policy of racial segregation.

The Garner case shows this most clearly, for there

the owner, while advising petitioners that they would

not be served, did not order them to leave and neither

he nor any of his employees or customers called the

police (G-. 30-31). Rather, the police officers who

made the arrest were called by a police officer on his

beat near the store (GK 34-35). Thus, the arrival

and subsequent actions of the police were entirely

unsolicited by any private citizen. The only police

officer who testified at petitioners’ trial stated that

the police acted because “ * * * the law says that this

place was reserved for white people and only white

people can sit there and that was the reason they were

arrested. * * * The fact that they were sitting

there and in my opinion were disturbing the peace

by their mere presence of being there I think was a

violation of Act 103. * * * The mere presence of

these negro defendants sitting at this cafe counter

seat reserved for white folks was violating the law

* * *” (G. 35-36).

Thus, the police officers’ action was not in any way

directed at protecting the property rights of the

owner of the drug store. Plainly, this direct, un

solicited, and affirmative action of the police rep

resents a form of State action designed to effectuate

a State policy of racial segregation. That action

is as clearly unconstitutional as if it had been

taken under a statute specifically requiring the segre

gation of the races. In the words of Mr. Justice

41

Frankfurter, dissenting on other grounds in Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT.S. 715, 727:

* * * For a State to place its authority be

hind discriminatory treatment based solely on

color is indubitably a denial by a . State of the

equal protection of the laws, in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment. * * *

Concededly, the role of the State in Briscoe and

Hoston is not quite as independent of private action

as it is in Garner. In Briscoe, the police were called

by a patron, a Greyhound bus driver (B. 33), and

in Hoston, the police were summoned by the store

manager (H. 30). But in neither case were the

police told that their assistance was needed for any

reason other than that Negroes were sitting at a

lunch counter reserved for whites. In Briscoe, the

call to the police advised that “ there were several

colored people sitting at the lunch counter. * * *

[The police] were called because of the fact that

[petitioners] were sitting in a section reserved for

white people” (B. 34-35). In Hoston, the police

were told that “ they [the Negroes] were seated at

the counter reserved for whites” (II. 30). There is

no evidence that either the bus driver or the

store manager summoned the police because petition

ers refused to leave upon request.11 Thus, in both

Briscoe and Hoston the calls to the police did no

11 In any event, it is hardly likely that a request to move