Boy Scouts of America v. Dale Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

March 29, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boy Scouts of America v. Dale Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. in Support of Respondent, 2000. 69827b8a-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/913a0921-be1e-40fd-ae2b-2c66f8cac34a/boy-scouts-of-america-v-dale-brief-amicus-curiae-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-et-al-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

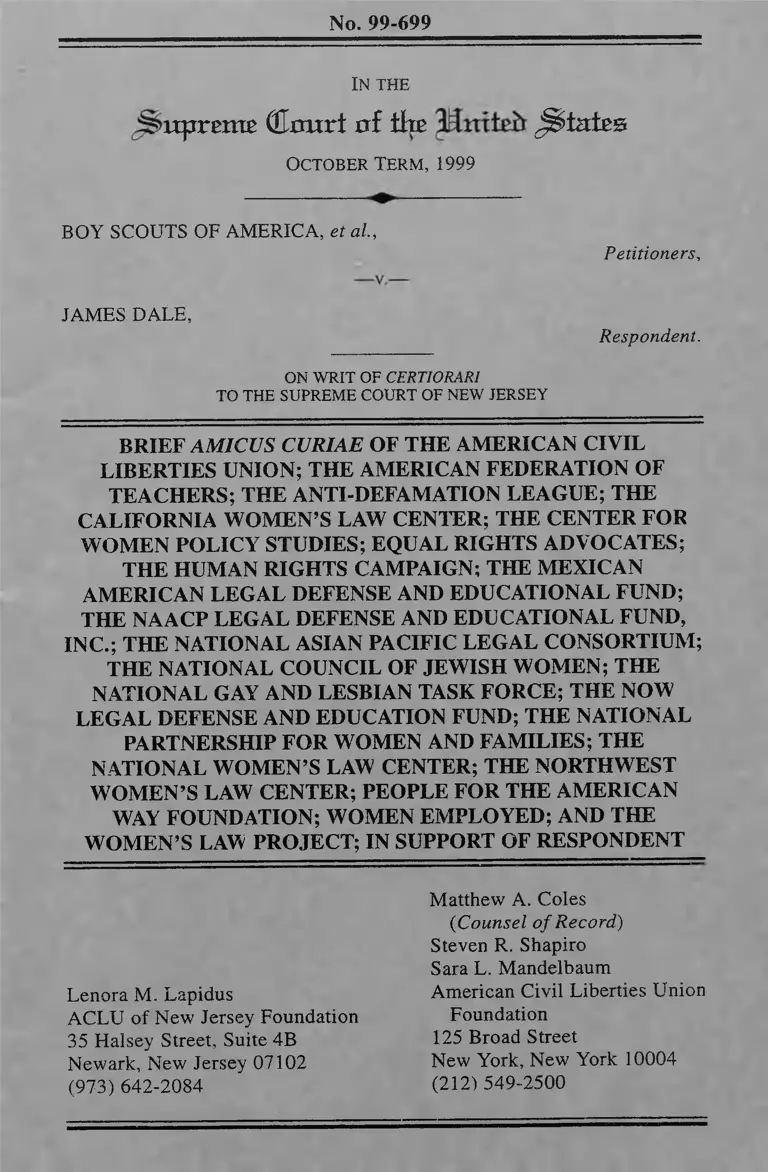

No. 99-699

IN THE

itprenie (Ernxri #f flie p la te s

October term , 1999

BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA, et al.,

Petitioners,

JAMES DALE,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW JERSEY

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION; THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS; THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE; THE

CALIFORNIA WOMEN’S LAW CENTER; THE CENTER FOR

WOMEN POLICY STUDIES; EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES;

THE HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN; THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND;

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC.; THE NATIONAL ASIAN PACIFIC LEGAL CONSORTIUM;

THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN; THE

NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE; THE NOW

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND; THE NATIONAL

PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN AND FAMILIES; THE

NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER; THE NORTHWEST

WOMEN’S LAW CENTER; PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN

WAY FOUNDATION; WOMEN EMPLOYED; AND THE

WOMEN’S LAW PROJECT; IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT

Matthew A. Coles

Lenora M. Lapidus

ACLU of New Jersey Foundation

35 Halsey Street, Suite 4B

Newark, New Jersey 07102

(973) 642-2084

( Counsel o f Record)

Steven R. Shapiro

Sara L. Mandelbaum

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, New York 10004

(212) 549-2500

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................................... iii

INTEREST OF AMICI . . . . ...................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ........ .........................................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT................................................. 3

ARGUM ENT............................................................................. 5

I. A CLAIMED RIGHT TO FREEDOM

OF ASSOCIATION DOES NOT

ENTITLE THE BOY SCOUTS TO

DISCRIMINATE AGAINST A

PROTECTED CLASS IN A PLACE

OF PUBLIC ACCOM M ODATION.................5

A. The Boy Scouts Are Not An

Intimate A ssociation.......................... .. . 6

B. Any Rights of Expressive

Association That May Exist In

This Case Are Not Unduly

Infringed By The Challenged

Nondiscrimination Order ....................... 9

l

Page

II. ANY INCIDENTAL BURDEN ON

THE BOY SCOUTS’ EXPRESSION

IS OUTWEIGHED IN THIS CASE

BY NEW JERSEY’S OVERRIDING

INTEREST IN ENSURING EQUAL

OPPORTUNITY ON THE BASIS

OF SEXUAL ORIENTATION........................ 16

A. New Jersey Has A Critically

Important Interest In Ensuring

Equality On The Basis Of

Sexual Orientation . ............. ...............16

B. New Jersey’s Interest In

Equality Is Unrelated To The

S u p p re s s io n O f F ree

Expression, And Its Law

Against Discrimination Limits

Expression No More Than

Necessary To Achieve Its

Stated G oal............................................... 20

CONCLUSION.........................................................................22

APPENDIX .................................. la

li

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

420 E. 80th v. Chin,

115 Misc. 2d 195 (1982), a ff’d, 97 A.D.

2d 390 (N.Y.A.D. 1st Dep’t 1983) ......................................... 19

Abood v. Detroit Board o f Education,

431 U.S. 209(1977) .............................................................. 12

Board o f Directors o f Rotary International

v. Rotary Club o f Duarte,

481 U.S. 537(1987) ...................................................... 5 ,7 ,16

Bob Jones University v. United States,

461 U.S. 574(1983) .......... 5

Bradwell v. Illinois,

83 U.S. 130(1872) .................................................................... 9

Brand v. Finkel,

445 U.S. 507(1980) ............................................................... 12

Burton v. Cascade School District Union

High School,

512 F.2d 850 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 423

U.S. 839(1975) ....................................................................... 19

Childers v. Dallas Police D ep’t,

513 F. Supp. 134 (N.D. Tex. 1981), a ff’d,

669 F.2d 732 (5th Cir. 1982) ................... 19

Page

City o f Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center,

473 U.S. 432 (1985) ........................................................ 18,19

Coon v. Joseph,

192 Cal. App. 3d 1269 (1987) ..................... ....................... 20

Frontiero v. Richardson,

411 U.S. 677(1973) .............................................................. 17

Cousins v. Wigoda,

419 U.S. 477 (1975) ....................................................... . . . 1 1

Daniel v. Paul,

395 U.S. 298 (1969) ........................................................ 11,18

DeSantis v. Pacific Telephone,

608 F.2d 327 (9th Cir. 1979) ........................................... .. . 19

Elrod v. Burns,

427 U.S. 347(1976) ............................................................... 12

Glover v. Williamsburg Local School Dist.,

20 F.Supp.2d 1160 (S.D.Ohio 1998) ................................ 19

Grant v. Brown,

39 Ohio St. 2d 112 (1974), cert, denied sub

nom. Duggan v. Brown, 420 U.S. 916 (1 9 7 5 )...................... 20

Heart o f Atlanta Motel v. United States,

379 U.S. 241 (1964) .............................................................. 18

Hishon v. King & Spalding,

467 U.S. 69 (1984) ......................................................... . . . . 5

iv

Page

Hubert v. Williams,

133 Cal. App. 3d Supp. 1 (1982) ........................ ................ 19

Hurley v. Irish American Gay, Lesbian &

Bisexual Group o f Boston,

515 U.S. 557 (1995) .......................................................... 4 ,10

Jones v. AlfredH. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968) .............................................................. 17

Keller v. State Bar o f California,

496 U.S. 1 (1990) ....................................................... .. 12

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) .................................................................... 9

McConnell v. Anderson,

451 F.2d 193 (8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

405 U.S. 1046(1972) ...................................................... 19,20

Meyer v. Nebraska,

262 U.S. 390(1923) ..................................................................6

Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo,

418 U.S. 241 (1974) .............................................................. 10

Moore v. City o f East Cleveland,

431 U.S. 494 (1977) ............................................... 7

Morell v. Department o f Alcoholic Beverage

Control,

204 Cal. App. 2d 504 (1962) .......................... ..................... 19

v

Page

Naboszny v. Podlesney,

92 F.3d 446 (7th Cir. 1996) .................................................. 20

New York State Club Ass ’n v. New York,

487 U.S. 1 (1988) ................... .................................... 6 ,12 ,16

Norton v. Macy,

417 F.2d 1161 (D.C. Cir. 1969) .......................... ................. 19

Norwood v. Harrison,

413 U.S. 455 (1973) ............................................................ 6,8

One Eleven Wines and Liquors Inc. v.

Division o f Alcoholic Beverage Control,

235 A.2d 12 (N.J. 1967) ........................................................ 19

Owles v. Lomenzo,

31 N.Y.2d 965 (1973) ............................................................. 20

Pickering v. Board o f Education,

391 U.S. 563 (1968) ............................................................... 15

Police Department v. Mosley,

408 U.S. 92 (1972) ..................................................................... 9

Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins,

447 U.S. 74(1980) ........................................................... 10,15

Roberts v. United States Jaycees,

468 U.S. 609 (1984) ........................................................ passim

Rolon v. Kulwitzky,

153 Cal. App. 3d 289 (1984) ................................................ 19

vi

Page

Romer v. Evans,

517 U.S. 620(1996) ........................................................ 18,20

Rowland v. Mad River Local School District,

730 F.2d 444 (6th Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

470 U.S. 1009(1985) ................................................... . . . . . 2 0

Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160(1976) ........................................................passim

Rutan v. Republican Party o f Illinois,

497 U.S. 62(1990) ................................................................ 12

S.A.G. v. R.A.G.,

735 S.W.2d 164 (Mo.App. 1987) ......................................... 19

School Board o f Nassau County v. Arline,

480 U.S. 273 (1987) .............................................................. 17

Smith v. Fair Employment and Housing

Commission,

30 Cal. Rptr. 2d 395 (Cal.App. 1994),

reversed on other grounds, 12 Cal. 4th 1143

(1996), cert, denied, 521 U.S. 1129 (1997) ....................... 18

Smith v. Liberty Mutual Insurance,

569 F.2d 325 (5th Cir. 1978) ............................................. 19

Stemler v. City o f Florence,

126 F.3d 856 (6th Cir. 1997), cert, denied,

523 U.S. 1118 (1998) ............................................................ 20

vii

Page

Texas v. Johnson,

491 U.S. 397(1989) ........................................................... 9,10

United States v. O'Brien,

391 U.S. 367 (1968) ............................................................... 16

Van Ooteghem v. Gray,

654 F.2d 304 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, denied,

455 U.S. 909 (1982) ............................................................... 20

Weaver v. Nebo School Dist.,

29 F.Supp.2d 1279 (D.Utah 1998) ....................................... 19

Weigand v. Houghton,

730 So. 2d 581 (Miss. 1999) .................................................. 19

Westside Community Schools v. Mergens,

496 U.S. 226 (1990) .............................................. 15

Zablocki v. Redhail,

434 U.S. 374(1978) ...................................................................7

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 2000e ..................................................................... 17

Legislative History

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 95,

1160,1833(1866) .................................................................... 17

Report o f C. Schurz, S. Exec. Doc. No. 2,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) ............... 17

Page

O ther Authorities

The Federalist Papers (Penguin Classics

Ed. 1987).................................................................................... 17

High am, STRANGERS IN THE LAND: PATTERNS

of America Nativism, 1860-1925 (Rutgers

University Press, 1992 ed.) ......................................................12

Hofstadter, The American Political

tradition (Vintage 1 9 7 4 )...................................................... 17

“Resolution on Racial Reconciliation on the

150th Anniversary of the Southern Baptist

Convention,” The Southern Baptist

Convention Annual (1995) ................................................... 9

Tribe, American Constitutional Law (2d ed. 1988) . . 7, 8

U.S. Dep’t of Education, National Center for

Education Studies, “The Condition of

Education” (1998) .......................................................................8

IX

INTEREST OF AM ICI'

This brief is filed by the following amici:

The American Civil Liberties Union, the American

Federation of Teachers, the Anti-Defamation League, the

California Women’s Law Center, the Center for Women Policy

Studies, Equal Rights Advocates, the Human Rights Campaign,

the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., the National

Asian Pacific Legal Consortium, the National Council of Jewish

Women, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the NOW

Legal Defense and Education Fund, the National Partnership for

Women and Families, the National Women’s Law Center, the

Northwest Women’s Law Center, People for the American Way

Foundation, Women Employed, and the Women’s Law Project.

The statements o f organizational interest are attached to

this brief as an appendix.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Boy Scouts of America is a federally chartered

corporation with five million members, including one million

youth members and 420,000 adult members in its Boy Scouts

program. The organization is run by a National Council, which

acts as its policymaking body. Dale v. Boy Scouts o f America

160 N J. 562, 571 (1999). The smallest unit in the organization

is the troop, and the average troop consists of 15 to 30 boys.

Pet.Br. at 40. The purpose o f the Boy Scouts is to promote the

ability o f boys to do things for themselves and others, and to

1 Letters of consent to the filing of this brief have been lodged with the Clerk

of the Court pursuant to Rule 37.3. Pursuant to Rule 37.6, counsel for amici

states that no counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or in part and

no person, other than amici, its members, or its counsel made a monetary

contribution to the preparation or submission o f this brief.

1

teach patriotism, courage, self-reliance and kindred virtues. Its

mission is to instill values in young people and prepare them to

make ethical choices. 160 N.J. at 573-74.

The organization aggressively solicits new members

through national advertising campaigns on television, in

magazines, and through local recruiting drives at schools and

elsewhere. “Any boy” is welcome to join the Boy Scouts. Id. at

590-91,609.

James Dale became a cub scout at the age of 8 and

remained in scouting until he reached the maximum age o f 18 in

1988. He was an exemplary scout. He was accepted in the adult

program as an Assistant Scoutmaster in 1989, and served for 16

months. Id. at 577-78.

While attending Rutgers University, Dale became a

member and eventually co-president of the Rutgers Lesbian/Gay

Alliance. During a conference on the psychological and health

needs of gay teens, he was interviewed by the Newark Star-

Ledger. An article later published in the paper quoted Dale

describing his second year at Rutgers. According to the Star-

Ledger, he said: “I was looking for a role model, someone who

was gay and accepting of me.” Dale was identified only as co

president o f the Rutgers Alliance. The Boy Scouts were not

mentioned in the article. Id. at 578; Joint Lodging Materials 10.

Within a month, Dale was told to sever his relations with

the Boy Scouts. When he asked for an explanation, he was told

that the Boy Scouts forbids membership to homosexuals. Five

months later, a lawyer for the Boy Scouts told Dale the

organization does not admit “avowed homosexuals.” 160 N.J.

at 579-80.

Dale sued, charging his expulsion from the Boy Scouts

violated New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination, which

forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation in public

2

accommodations. The trial court granted summary judgment to

the Boy Scouts, holding that: (1) the organization was not a

public accommodation under New Jersey law; (2) if it were, it

would meet the law’s exception for organizations which are

distinctly private; and (3) in any case, subjecting the Boy Scouts

to New Jersey’s antidiscrimination law would violate the

organization’s freedom of expressive association. Id. at 580.

The Appellate Division reversed on all three points,

holding that the Boy Scouts is a public accommodation under

the L.A.D. and is not distinctly private. It also rejected the

Scouts’ freedom of intimate and expressive association claims.

308 N.J.Super. 516 (1998). That decision was in all respects

affirmed by the New Jersey Supreme Court. 160 N.J. 562.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Boy Scouts of America has more than a million

young members and 420,000 adult members in its scouting

program. It aggressively solicits new members and tells the

public that “any boy” is welcome to join. It holds that moral

fitness is a matter of what an individual’s own head and heart

tell him is right, and it discourages its scoutmasters from

discussing sexuality at all. Under these circumstances, the Boy

Scouts has no more right to discriminate in violation o f state law

than the Rotary Club or the Jaycees. Like those other

organizations, whose earlier efforts to evade the civil rights laws

were soundly rejected by this Court, the exclusionary anti-gay

membership policy that the Boy Scouts now so vigorously

defends falls outside the scope o f any associational or expressive

freedom protected by the First Amendment.

1. A Boy Scout troop is not an intimate association.

Lack o f selectivity alone disqualifies it. More fundamentally, its

members do not choose each other; they make no decision about

who shall or shall not be members of the troop.

3

2. New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination does not

affect any expressive activity undertaken by the Boy Scouts, or

any message the Boy Scouts may wish to convey about gay

people. For that reason, Hurley v. Irish American Gay, Lesbian

& Bisexual Group o f Boston 515 U.S. 557 (1995), does not

control this case. State regulation of who takes part in an act of

expression, like a parade or a demonstration, interferes directly

with a speaker’s message. By contrast, insisting that an

association not discriminate in its membership ordinarily does

not interfere with the organization’s message because there is

little risk that an association open to the public will be thought

to be making a statement through the composition of its

membership. The fact that James Dale is seeking to remain a

scoutmaster does not alter that understanding since whatever

leadership responsibilities Dale’s position entails have nothing

at all to do with the basis on which Dale was excluded from the

Boy Scouts.

3. Any incidental burden on the Boy Scouts’ freedom of

expressive association is outweighed by the state’s compelling

interest in ensuring equality. In banning sexual orientation

discrimination, New Jersey sought to include in ordinary life a

group of Americans unfairly excluded from much of it. That is

an important interest, unrelated to the suppression of expression;

the Law Against Discrimination is narrowly tailored to

effectuate it.

To hold otherwise would be to allow every effort to halt

discrimination to be checkmated by an assertion o f associational

autonomy. The analysis this Court has used to keep equality

and expression in balance has worked well for both. The Court

should reaffirm it in this case.

4

ARGUMENT

I. A C LAIM ED R IG H T TO FREEDOM OF

ASSOCIATION DOES NOT ENTITLE THE BOY

SCOUTS TO DISCRIMINATE AGAINST A

PROTECTED CLASS IN A PLACE OF PUBLIC

ACCOMMODATION

This case does not involve a right to associate as much

as an asserted right to disassociate. While those two rights are

often opposite sides of the same coin, they are not identical.

And when, as here, the desire to exclude is directed against a

group that the state has chosen to protect from unequal

treatment, the conflict with the state’s overriding interest in

enforcing its civil rights laws becomes most acute. Over the past

two decades, therefore, this Court has crafted a set of rules

designed to preserve freedom of association without allowing it

to become a subterfuge for discrimination based on animus or

ignorance. In applying those rules, moreover, this Court has

generally reacted with great skepticism to claims that important

institutions in the social and economic life of the nation have a

constitutional right to perpetuate discrimination.

Indeed, this Court has never struck down any civil rights

law as a violation of the freedom to associate. Instead, the Court

has consistently rejected such claims in a wide variety of

contexts. E.g., Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976)(upholding civil rights claim against private school that

discriminated on the basis of race); Bob Jones University v.

United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983)(upholding denial of tax-

exempt status based on racial discrimination); Hishon v. King &

Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) (upholding sex discrimination

judgment against law firm partnership); Roberts v. United States

Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984)(upholding state law requiring

Jaycees to admit women as members); Board o f Directors o f

Rotary In t’l v. Rotary Club o f Duarte, 481 U.S. 537

5

(1987)(upholding state law requiring Rotary Club to admit

women as members); New York State Club Ass ’n v. New York,

487 U.S. 1 (1988)(upholding application o f local civil rights law

that prohibits discrimination by private clubs that solicit

business from nonmembers).

Despite this extensive body of case law, the Boy Scouts

claims that it is entitled to a constitutional exemption from New

Jersey’s antidiscrimination law because, it contends, it violates

the organization’s rights to both intimate association and

expressive association. In fact, it violates neither. The Boy

Scouts relies on a conception of those rights that is so potentially

limitless it would enable virtually any group to evade the civil

rights laws by proclaiming its discriminatory membership

policies as evidence of selectivity and an ideological point of

view. This Court, however, has consistently and correctly

rejected that false syllogism. As the Court observed in Norwood

v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 470 (1973), “the Constitution places

no value on discrimination.” Thus, while “[ijnvidious private

discrimination may be characterized as a form of exercising

freedom of association protected by the First Amendment. . . it

has never been accorded affirmative constitutional protection.”

Id. at 470. See also Runyon v. McCrary, A l l U.S. at 176. The

New Jersey Supreme Court correctly applied those principles

below, and its decision should be affirmed.

A. The Boy Scouts Is Not An Intimate Association

The Boy Scouts invokes two distinctly different aspects

of the constitutionally protected right of intimate association: the

right to form “highly personal relationships” in which people

share an intense commitment to each other, Roberts, 468 U.S. at

618, and the right o f parents to direct the upbringing o f their

children, see, e.g., Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

Both rights enjoy very substantial protection against government

interference in proper circumstances. This case, however, does

6

not present those circumstances.

The right of intimate association protects an individual’s

decisions regarding those with whom she or he will form deep

personal attachments, and with whom she or he will make

intense personal commitments. Roberts 468 U.S. at 617, 619-

20; see also, Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978); Moore

v. City o f East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494 (1977).

Under this Court’s jurisprudence, one of the

distinguishing characteristics of an intimate association is “a

high degree of selectivity in decisions to begin and maintain the

affiliation.” Roberts, 468 U.S. at 620. By contrast, the record

below demonstrates that the goal o f the Boy Scouts is to recruit

as many members between the ages of eleven and seventeen as

possible, with the hope o f attracting a broadly diverse

membership. Dale, 160 N.J. at 609. Based on this record

evidence, the New Jersey Supreme Court found that the Boy

Scouts were “unselective” in their membership. Id. That

finding, which is not questioned in this Court, see Pet.Br, at 39-

41, is alone fatal to any claim o f intimate association. See

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 621.2

There is an additional problem with any claim of

intimate association on the facts of this case, however. The Boy

Scouts does not actually grant its members the associational

right that the organization now asserts as the basis for defying

New Jersey’s antidiscrimination law. Unlike the Jaycees in

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 540-41, and the Rotarians in Duarte, 481

U.S. at 613-14, individual members of boy scout troops do not

select their fellow scouts. Dale, 160 N.J. at 576-77. Rather, the

2 "The less intimate and more attenuated the association — and the more the

association affects the public realm and access to the privileges and

opportunities available in that realm - the greater the state’s power to

regulate an organization’s exclusionary practices.” TRIBE, AMERICAN

Constitutional Law (2ded. 1988), §16-15 at 1480 n.37.

7

creation o f a scout troop is much more akin to student class

assignments, which are usually determined without any

significant input by the students themselves. See Tribe, § 16-15

at 1479 (school may not rely on associational rights o f children

when their choices are “obviously dominated” by adults). The

average primary school class is about the same size as the

average boy scout troop, it is similarly led by an adult, and it

requires a substantial commitment of time and energy by the

children involved.3 Whatever attenuated right of intimate

association primary school students may have in the composition

of their class, the power of the state to prohibit school officials

from engaging in unlawful discrimination when they decide

whom to admit is no longer open to serious question. See

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. at 177-79. The same principle

applies with equal force here and provides ample support for the

decision below.

The Boy Scouts fares no better by alleging that New

Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination somehow infringes the

constitutional right of parents to direct the upbringing of their

children. The right o f parental autonomy simply does not

embrace the right to insist that a public accommodation indulge

a parent’s discriminatory views by barring disfavored groups

from goods and services that are otherwise available to the

general public. Thus, while some parents may wish to send their

children to an all-white school, that fact does not excuse the

school from the need to comply with the state’s

antidiscrimination laws. Runyon, 427 U.S. at 177, and

Norwood, 413 U.S. at 461-63. Indeed, a working definition of

unlawful discrimination is that it is the transformation o f private

3 U.S. Dep’t o f Education, National Center for Education Statistics, The

Condition o f Education, 1998, at 1 (average primary school class size is 24

in public school, 22 in private school) and at “Indicator 38" (avg. hours spent

in the classroom by a primary school teacher in a year is 958). Compare Pet.

Br. at 40 (a typical boy scout troop consists o f 15 to 30 boys).

8

prejudices into market decisions.

Accordingly, there is no legal significance to the Boy

Scouts’ claim that their decision to exclude James Dale from the

Scouts solely because he is gay reflects what the organization

perceives to be the moral disapproval of at least some of its

scouting parents. Even if that perception is accurate, it cannot

be controlling. Most forms o f discrimination that are now

prohibited by our civil rights laws are or were justified on the

basis of deeply held moral views. See, e.g., Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1, 3 (1967)(trial judge’s finding that segregation was

ordained by God); “Resolution on Racial Reconciliation on the

150th Anniversary of the Southern Baptist Convention,” The

Southern Baptist Convention Annual (1995) at 80-81

(acknowledging denomination’s support of slavery and

segregation and apologizing to African-Americans); Bradwell

v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130, 141 (Bradley, J., concurring) (1872)

(natural unsuitability of women to work).

The right to direct the education of one’s children is not

a right to decide who else may attend school or who may teach.

Similarly, the right to provide one’s child with a scouting

experience is not a right to decide that only members of favored

groups may be permitted to join the troop or to lead it.

B. Any Rights of Expressive Association That May Exist

In This Case Are Not Unduly Infringed By The

Challenged Nondiscrimination Order

In Roberts, 468 U.S. at 618, this Court recognized that

freedom of association serves an important “instrumental” value

in promoting freedom of expression. Accordingly, the

government has no more right to dictate the content of the

message delivered by a group, see, e.g., Police D ep’t v. Mosley,

408 U.S. 92 (1972), than it has to dictate the content of the

message delivered by an individual, see, e.g., Texas v. Johnson,

9

491 U.S. 397 (1989). That principle does not assist the Boy

Scouts in this case, however, because the nondiscrimination law

that New Jersey is seeking to enforce is plainly content-neutral,

and leaves the Boy Scouts free to advocate whatever position the

organization chooses about gay people.

This case is thus fundamentally different from Hurley v.

Irish-American Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Group o f Boston, 515

U.S. 557, on which the Boy Scouts so heavily relies. That case

arose out of a longstanding dispute about whether the private

organizers of Boston’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade had to permit a

gay and lesbian group to march under its own banner. In

holding that they did not, this Court rejected the view that the

parade could appropriately be characterized as a place of public

accommodation in the ordinary sense of the term. Rather, the

Court concluded, the parade represented a traditional form of

expressive activity and the sponsors of the parade, no less than

the publishers o f a newspaper, Miami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974), were entitled to determine the

message they wished to convey. Under the contrary rule

proposed by the state, the Court explained, “any contingent of

protected individuals with a message would have the right to

participate in petitioners’ speech, so that the communication

produced by the private organizers would be shaped by all those

protected by the law who wished to join in with some expressive

demonstration of their own.” Hurley, 515 U.S. at 573.

Had Massachusetts been allowed to insist that the lesbian

and gay delegation be admitted to the parade in Hurley,

observers along the way might well have assumed that the

organizers included the lesbian and gay delegation in the parade,

and made their message a part of its message. Id. at 575. By

contrast, there is little risk that an association will be understood

to be making a statement through the identity of its members,

particularly if the association has millions of members and is

open to the public. See Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins,

10

447 U.S. 74, 87 (1980); accord Dale, 160 N.J. at 571. Our

society is far too diverse for that.

The Boy Scouts would like to read Hurley for the

proposition that the state can never enforce its civil rights laws

over the opposition of any organization that purports to represent

a set of values that conflicts with the state’s antidiscrimination

goals. But the holding of Hurley clearly does not go so far.

Certainly, nothing in the Court’s opinion purports to overrule

Roberts or even to question it.

To be sure, the ACLU and other members o f the civil

rights community are acutely aware that government, attempts

to regulate the membership of an expressive association pose

their own First Amendment dangers. Cf. Cousins v. Wigoda,

419 U.S. 477 (1975). But this case does not involve a targeted

or viewpoint-based effort to regulate an association’s

membership; it involves instead the indirect effect of a neutrally

applied public accommodations law designed to promote civil

rights. On these facts, any impact of that law on First

Amendment rights is incidental, at best, and must be balanced

against the risk to civil rights enforcement if an organization’s

selective membership policies become their own justification for

a claimed right to discriminate. Nor is that concern a fanciful

one. In the 1950s and 1960s, many businesses in the deep South

converted overnight into “private clubs” where every white

patron was entitled to automatic membership and every potential

black customer was barred at the door. See Daniel v. Paul, 395

U.S. 298 (1969). With this history in mind, the Court has been

appropriately wary o f any claim that the message of an

association is inextricably tied to its membership policies, so that

the latter cannot be regulated without abridging the former.4

4 Recognition of the fact that there is a “close nexus between the freedoms of

speech and assembly” does not mean “that in every setting in which

individuals exercise some discrimination in choosing associates, their

11

There may be rare situations where that is true, In New

York State Club Ass ’n. v. New York, 487 U.S. at 13, this Court

recognized the possibility that an association might show that it

was organized for a specific expressive purpose that it could not

effectively advocate unless it could limit its membership to be

consistent with its message. For example, an organization

founded to promote anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism5 might

well be right that simply having members who admit to being

Jews or Catholics is so inconsistent with its core mission that the

First Amendment allows it to exclude them. Given the

competing interests at stake, however, amici do not believe it is

possible to avoid the task of “carefully assess[ing]” the extent to

which application o f the state’s antidiscrimination laws will

actually interfere with the organization’s core purposes.

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 620.6

selective process of inclusion and exclusion is protected by the Constitution.”

New York State Club Ass ’n, Inc. v. City o f New York, 487 U.S. at 13 (citations

and internal quotations omitted).

5 Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism,

1860-1925 (Rutgers University Press, 1992 ed.), at 286-299 (“The Klan

Rides”).

6 This approach is also consistent with the methodology that the Court has

employed in other association contexts. In the political patronage cases, the

Court has asked whether party affiliation has any relevance to job

performance, which is simply another way o f asking whether the ability of

the prevailing political party to deliver its message will be impeded if it is

forced to associate with members of the opposing party by hiring (or

retaining) them to fill certain critical positions. See Rutan v. Republican

Party o f Illinois, 497 U.S. 62 (1990); Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S. 507 (1980);

Elrod v. Bums, 427 U.S. 347 (1976). In the compelled dues cases, the Court

has focused on whether the organizational dues are being spent for a purpose

that is “germane” to the reason that the dues were collected in the first place,

which is simply another way of asking whether the challenged expenditure

is in furtherance o f the organization’s central purpose. See, e.g., Abood v.

Detroit Board o f Education, 431 U.S. 209 (1977); Keller v. State Bar o f

12

That is precisely the inquiry' that this Court undertook in

Roberts, when it determined that any impact on the expressive

message of the Jaycees was incidental at best. Id, at 627.7 It is

also precisely the inquiry undertaken by the New Jersey courts

in this case, which is what led them to conclude that:

The organization’s ability to disseminate its

message is not significantly affected by Dale’s

inclusion because: Boy Scout members do not

associate for the purpose of disseminating the

belief that homosexuality is immoral; Boy

Scouts discourage its leaders from disseminating

any views on sexual issues; and Boy Scouts

include sponsors and members who subscribe to

different views in respect of homosexuality.

160 N.J. 2d at 612.

These conclusions could be challenged only if the Boy

Scouts were now to demonstrate that the organization is in fact

defined by its view that homosexuality is immoral, that this view

is integral to who the Boy Scouts are, and that its members

decided to join the organization because o f its intolerant views

California, 496 U.S. 1 (1990).

7 Justice O ’Connor’s concurring opinion in Roberts suggests that the

constitutionally relevant line is between expressive associations and

commercial associations. 468 U.S. at 632-35. That line, however, would not

account for the result in Runyon v. McCrary. A school is the quintessential

expressive association, Roberts, 468 U.S. at 636 (O ’Connor, J.). Yet the

Runyon Court unequivocally held that while the private school defendants in

that case could advocate segregation, they could not express that view by-

segregating their student body. That was not, we believe, because the schools

charged tuition, but rather because the core purpose o f the schools was to

educate, and because the Constitution places so little (if any) value on

discrimination as a means of expression. Runyon, 427 U.S. at 176. The

same analysis applies here.

13

about homosexuality. Even in its submissions to this Court,

however, the Boy Scouts has stopped well short of that claim.

Instead, the Boy Scouts has tried to shift the focus o f its

argument from a question o f membership to a question of

leadership. The theory, apparently, is that an organization’s

leadership choices are entitled to deference by the state — even

when they conflict with the state’s antidiscrimination laws —

because those choices represent an organizational statement of

some sort.

That argument is flawed on the facts of this case for

several critical reasons. First, any act o f intentional

discrimination can be said to represent an organizational

statement but that cannot be a sufficient justification forignoring

the civil rights laws or those laws would quickly become a dead

letter. See Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160. Second, as this

Court made clear in the patronage cases, leadership is not a

matter of title but a matter of job responsibility. See n.6, supra.

Here, James Dale is seeking to remain an assistant scoutmaster,

which is not a policymaking position within the Boy Scouts.

Dale, 160 N.J. at 572-73, 577. Third, the fact that Dale is gay

does not conflict with his non-policymaking responsibilities.

While it may be fair to characterize scoutmasters as teachers in

some sense, they are specifically instructed by the Boy Scouts to

avoid any teaching on issues o f sexuality and religion. If the

subject comes up, the prescribed answer is that such matters are

better discussed at home. Id. at 160 N.J. at 575, 614-15.

This would be a different case if Dale were actively

seeking to undermine a message about homosexuality that the

Boy Scouts were actively seeking to promote, but the record

does not support either proposition. As the New Jersey Supreme

Court noted: “[Tjhere is no indication that Dale intends to

‘teach’ anything whatsoever about homosexuality as a scout

leader, or that he will do other than the Boy Scouts instructs him

to do — refer boys to their parents on matters o f religion and

14

sex.” Id. at 623.

In the final analysis, the position o f the Boy Scouts

appears to be that it is prepared to accept gay members and even

gay scoutmasters as long as they remain safely closeted, but it

will not accept the presence of anyone who is openly gay. That

attitude would not be tolerated for a moment if the Boy Scouts

were claiming that it would accept Jewish or Catholic scouts as

long as they kept their faith hidden. The price of equal

opportunity in this country should not be a requirement to

disguise one’s identity. To the contrary, the entire goal of the

antidiscrimination laws is that people should be judged on what

they can do and not on who they are.

It is true that since Dale is openly gay, the better he is at

his job as a scoutmaster, the more some may think that being

gay is “acceptable.” That is a “danger” with anyone who is open

about his or her ethnicity or religion. But the Boy Scouts’ fear

that this will be seen as its message is simply without much

basis in reality. What a teacher says outside of school is usually

not fairly attributable to the school, see Pickering v. Board o f

Education, 391 U.S. 563, 572 (1968); Westside Community

Schools v. Mergens, 496 U.S. 226,250 (1990), particularly if the

school makes its wish not to take a position clear. See

Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74, 87 (1980).

Any danger o f attribution here is virtually nonexistent because,

as the New Jersey Supreme Court found, the Boy Scouts tells the

public that all boys are welcome to join. 160 N.J. at 609. All

that an organization can really be understood to have “said” by

retaining someone protected against discrimination by the civil

rights laws is that the organization obeys the law. If anything,

that is a message that the Boy Scouts presumably endorses.

15

II. ANY INCIDENTAL BURDEN ON THE BOY

SCOUTS’ EXPRESSION IS OUTWEIGHED IN

THIS CASE BY NEW JERSEY’S OVERRIDING

I N T E R E S T IN E N S U R I N G E Q U A L

OPPORTUNITY ON THE BASIS OF SEXUAL

ORIENTATION

In Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, Board

o f Directors o f Rotary, In t’l v. Duarte, 481 U.S. 537, and. New

York State Club A ss’n v. City o f New York, 487 U.S. 1, this

Court essentially applied the analysis it first developed in United

States v. O ’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968), for evaluating

government actions which, while not aimed at a speaker’s

message, limit the means one can use to express it. That test

requires that the government show: (1) that it is acting in pursuit

of an “important” interest;8 (2) that the interest is unrelated to the

suppression of free expression; and (3) that the approach it has

adopted is “narrowly tailored” to achieve the government’s goal.

Each o f those requirements was easily satisfied in the 1980s

trilogy; each of those requirements is also easily satisfied here.

A. New Jersey Has A Critically Important

Interest in Ensuring Equality On The Basis of

Sexual Orientation

One of the central visions on which this nation was

founded was that ours would be a society in which talent, skill

and hard work would be what mattered. It is an idea that runs

through American thought, from James Madison’s Federalist

8 Roberts described the necessary government interest as “compelling” but,

as the O ’Brien Court pointed out, there is no magic in the terminology used

to describe what must be a very significant government interest. See Roberts,

468 U.S. at 623; O ’Brien, 391 U.S. at 376-77.

16

No. 10, 9 through the debates on the adoption o f the civil war

amendments,10 to the opinions of this Court.11

That vision has never been realized. Despite our

aspirations, we have a long, sad history o f judging people not by

what they are capable of doing, but by such extraneous things as

race, religion, national origin, sex, disability and sexual

orientation.

Civil rights laws are enacted to bring our nation closer to

a society that does not function on the basis of group stereotype.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was designed to end “private

injustices”against African-Americans who, in the wake o f the

Civil War, were still unable to find work or housing in large

parts of the country. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409, 422-36 (1968). The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was aimed

at overcoming “prejudice,” “insensitivity,” and “ignorance” so

that people with disabilities would not be denied “jobs or other

benefits.” School Board o f Nassau County v. Arline, 480 U.S.

273, 279 , 284 (1987). The caption o f Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act plainly expresses its goal of “equal

opportunity.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e.

Thinking in economic terms, as law often does, it is easy

to see that the chance to have and hold a job or an apartment on

equal terms has to be an essential element of any society that

treats people fairly. But the somewhat more intangible value of

9 The federalist Papers (Penguin Classics Ed. 1987), at 124.

10 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., l a Sess.,95, 1160,1833 (1866); see also Report

o f C. Schurz, S. Exec. Doc. No. 2, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866).

11 Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677,686-87 (1973)(relegating an entire

class o f citizens to an inferior status “without regard to actual capabilities”

violates a “basic concept o f our system”); see also Hofstadter, The

American Political Tradition (Vintage 1974), at 3-21.

17

not being shut out o f lunch counters, theaters, businesses and

associations that say they are open to the public is every bit as

essential. Indeed, when President Kennedy proposed what

became the Civil Rights Act o f 1964, he noted that no action

could be “more contrary to the spirit o f our democracy,” and

none “more rightfully resented,” than being barred from public

accommodations. See Daniel v. Paul, 395 U.S. at 306. Thus,

the overriding purpose of civil rights legislation, as this Court

explained just a few years ago, is to make it possible for those

protected by the law to participate in the “almost limitless

number of transactions and endeavors that constitute ordinary

civic life in a free society.” Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 631

(1996). Stated more broadly, the purpose of the civil rights law

is to protect basic human dignity. See Heart o f Atlanta Motel

v. United States, 379 U.S. 241, 250 (1964).

This Court has said that laws designed to ensure equal

opportunity and equal access to goods and services serve

“compelling state interests of the highest order.” Roberts, 468

U.S. at 624.12 Given the central place of fair treatment and

12 It has occasionally been suggested that the government has an overriding

interest in forbidding only those forms of discrimination that it would need

a compelling justification to practice; or, to put it another way, that the

government only has an overriding interest in ending discrimination against

those defined by “suspect classifications.” See Smith v. Fair Employment and

Housing Commission, 30 Cal. Rptr.2d 395,404 (Cal.App. 1994), reversed on

other grounds, 12 Cal.4th 1143 (1996), cert, denied, 521 U.S. 1129 (1997).

But apart from using similar terminology, there is no necessary connection

between the two ideas, no reason why the Court’s analysis of when ensuring

equality is overriding should depend on when a reason to treat people

unequally is deemed compelling. Indeed, in City o f Cleburne v. Cleburne

Living Center, 473 U.S. 432 (1985), this Court held that discrimination

against the mentally disabled was not suspect at least in part because of

significant government efforts to end discrimination. The Court speculated

that those efforts might withstand heightened scrutiny even as it mled that

discrimination against the mentally disabled does not require it. Id. at 443-45.

18

personal initiative in the American vision o f society, it may be

that virtually any law truly designed to ensure equal opportunity

serves government interests o f the highest order. The Court

need not decide that in this case, however. At a minimum, there

can be no doubt that lesbians and gay men have historically been

denied equal opportunity to participate in American life. Gay

people have been denied employment as everything from

telephone operators to librarians to budget analysts to teachers

to police officers to mail room clerks.13 Gay people have lost

their homes (as have heterosexuals who lived with gay people),

and been told not to dance with each other, not to eat together in

booths, and not to “hang out” together in bars and clubs.14 Gay

people have had their families tom apart and their children left

in peril.15 Lesbians and gay men have been subjected to

13 See, e.g., DeSantis v. Pacific Telephone, 608 F.2d 327 (9th Cir. 1979);

McConnell v. Anderson, 451 F.2d 193 (8th Cir. 1977); Norton v. Macy, A ll

F.2d 1161 (D.C. Cir. 1969); Gloverv. Williamsburg Local School Dist., 20

F.Supp.2d 1160 (S.D.Ohio 1998); Weaver v. Nebo School Dist., 29

F.Supp.2d 1279 (D.Utah 1998); Burton v. Cascade School District Union

High School, 512 F.2d 850 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 839 (1975);

Childers v. Dallas Police D ep’t, 513F.Supp. 134(N.D.Tex. \9%\) off’d, 669

F.2d 732 (5th Cir. 1982); Smith v. Liberty Mutual Insurance, 569 F.2d 325

(5th Cir. 1978).

14 See, e.g., 420 E.80th v. Chin, 115 Misc.2d 195 (1982), aff’d , 97 A.D. 2d

390 (N.Y.A.D. 1st Dep’t 1983); Hubert v. Williams, 133 Cal.App.3d Supp.

1(1982); Morell v. Dept, o f Alcoholic Beverage Control, 204 Cal.App.2d 504

(1962); Rolon v. Kulwitzky, 153 Cal.App.3d 289 (1984); One Eleven Wines

and Liquors Inc. v. Div. o f Alcoholic Beverage Control, 235 A.2d 12 (N.J.

1967).

15 See, e.g., Weigand v. Houghton, 730 So.2d 581, 588 (Miss. 1999)(McRae,

J., dissenting)(child placed in home with convicted felon and wife abuser

because father was gay); S.A.G. v. R.A.G., 735 S.W.2d 164 (Mo.App.

1987)(mother denied custody in favor of alcoholic father because mother was

a lesbian).

19

unspeakable violence for being gay.16

The history of gay people in America is in large measure

a history of being forced underground,17 away from the easy

participation in “ordinary civic life” that most Americans take

for granted. See Romer, 517 U.S. at 631. New Jersey

committed itself to creating equal opportunity for a group of

Americans who truly have been excluded from equal

participation in ordinary life when it added sexual orientation to

its Law Against Discrimination. That is a government interest

of the highest order. See Roberts, 468 U.S. at 624.

B. New Jersey’s Interest in Equality Is Unrelated

To The Suppression Of Free Expression, And

Its Law Against Discrimination Limits

Expression No More Than Necessary To

Achieve Its Stated Goal

New Jersey ’ s interest in ensuring that the gay people who

live there have an equal opportunity to participate in society is

unrelated to the suppression of free expression. See, e.g.,

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 623. Like the Minnesota public

16 See, e.g., Naboszny v. Podlesney, 92 F.3d 446 (7th Cir. 1996); Stemler v.

City o f Florence, 126 F.3d 856 (6th Cir.1997), cert, denied, 523 U.S. 1118

(1998); Coon v. Joseph, 192 Cal.App.3d 1269 (1987).

17 See Katz, Gay American History; see also State ex.rel. Grant v. Brown, 39

Ohio St. 2d 112 (1974), cert, denied sub nom. Duggan v. Brown; 420 U.S.

916 (1975)(Greater Cincinnati Gay Society not permitted to incorporate);

Owles v. Lomenzo, 31 N.Y.2d 965(1973)(overruling a similar decision by the

New York Secretary o f State); Rowland v. Mad River Local School Dist., 730

F.2d 444, 446 (6th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 470 U.S. 1009 (1985)(guidance

counselor fired in part because she told coworkers she was bisexual); Van

Ooteghem v. Gray, 654 F.2d 304 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 909

(1982)(overtuming discharge o f gay man who spoke in favor of civil rights

at county commission); McConnell v. Anderson, 451 F.2d 193 (8th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 405 U.S. 1046 (1972)(same).

20

accommodations law in Roberts, New Jersey’s Law Against

Discrimination does not distinguish on the basis of viewpoint or

content. Id. While the Boy Scouts claim that the application of

New Jersey’s law to it is motivated by a desire to hamper its

ability to express its views, the criteria applied by the New

Jersey Supreme Court to determine that the organization is a

public accommodation covered by the Law Against

Discrimination are undeniably neutral, and have been applied to

similar organizations with different views. Dale, 160 N.J. at

589-602. Finally, the central purpose of ensuring equality in

organizations that open themselves to the general public can be

achieved only by forbidding identity-based discrimination. See

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 626, 628. The Constitution does not

disable the government from prohibiting discrimination in places

of public accommodation. See Runyon, 427 U.S. at 176.

21

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the New

Jersey Supreme Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Matthew A. Coles

('Counsel o f Record)

Steven R. Shapiro

Sara L. Mandelbaum

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, New York 10004

(212) 549-2500

Lenora M. Lapidus

ACLU of New Jersey Foundation

35 Halsey Street, Suite 4B

Newark, New Jersey 07102

(973) 642-2084

Dated: March 29, 2000

22

A P P E N D I X

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with nearly

300,000 members dedicated to the principles o f liberty and

equality embodied in the Constitution and our nation’s civil

rights laws. The ACLU of New Jersey is one o f its statewide

affiliates. Since its founding in 1920, the ACLU has frequently

advocated in support of the right to freedom of association, both

on its own behalf and on behalf of other groups. See, e.g.,

Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Group of

Boston, 515 U.S. 557 (1995). The ACLU has also frequently

argued in favor of the state's constitutional authority to eliminate

discrimination in places of public accommodation, see, e.g.,

Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984), in part

through the work of both its Lesbian and Gay Rights Project,

and its Women's Rights Project. Because this case once again

requires the Court to consider when protected association

crosses the line into forbidden discrimination, its proper

resolution is a matter of significant concern to the ACLU and its

members.

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is a

national labor union that represents over one million members,

who work in public schools, community colleges, universities,

state government, and health care. The vast majority of AFT

members are employed as teachers and teaching assistants in

public primary and secondary schools. AFT has a long-standing

interest in First Amendment and civil rights issues that have an

impact on AFT's membership, and this interest has resulted in

AFT participating in a number o f amicus briefs before the

Supreme Court.

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), one of the

nation’s oldest civil rights organizations, was founded in 1913

to promote good will among all races, ethnic groups, and

religions. As set out in its charter, ADL’s “ultimate purpose is

to secure justice and fair treatment to all citizens alike and to put

la

an end forever to unjust and unfair discrimination against and

ridicule of any sect or body of citizens.” To this end, ADL is

committed to eradicating discrimination in public

accommodations. ADL filed amicus briefs with this court in

Robert v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984), New York

State Club Assn. v. New York, 487 U.S. 1 (1988) and Board o f

Directors o f Rotary Int 7 v. Rotary Club o f Duarte, 481 U.S. 537

(1987), among other relevant cases.

The California Women's Law Center (CWLC) is a

private, nonprofit public interest law center specializing in the

civil rights of women and girls. Established in 1989, the CWLC

places a strong emphasis on advancing the rights of women and

girls in employment and education. CWLC has authored

numerous amicus briefs, articles, and legal education materials

on discrimination, and litigates discrimination cases. This case

raises questions with an enormous impact on the issues which

concern the California Women's Law Center.

The Center for Women Policy Studies is an

independent, national, multiethnic and multicultural feminist

policy research and advocacy institution, founded in 1972. We

currently are working with a network of state legislators to

ensure that lesbians and gay men have full and equal legal

protection from violence and discrimination. The Court’s

decision in this case will have a significant impact on legislators’

ability to enact comprehensive laws to eliminate discrimination

against sexual orientation, and to include sexual orientation in

state hate crimes statutes.

Equal Rights Advocates (ERA) is a San Francisco-

based, public interest law firm focused on ending discrimination

against women and girls. ERA works to achieve women’s

equality and economic security through litigation, education,

legislative advocacy and practical advice and counseling. Since,

its inception ERA has worked tirelessly to end gender

2a

discrimination and establish gender equality. ERA believes in

the value of coalitions and alliances, and works closely with

groups in the women’s, civil rights, and immigrant rights

communities to achieve social justice and equal opportunity.

The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) is the nation's

largest gay and lesbian civil rights organization, with over

360,000 members nationwide. HRC is devoted to fighting and

ending discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and to

protecting the basic civil and human rights of gay, lesbian, and

bisexual Americans. To this end, HRC has provided federal and

state legislative, regulatory and judicial advocacy, media and

grassroots support on a range of initiatives affecting gay, lesbian

and bisexual individuals who suffer discrimination on the basis

o f their sexual orientation, including the Employment Non-

Discrimination Act.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund (MALDEF) is a national not-for-profit

organization that protects and promotes the civil rights of more

than 29 million Latinos living in the United States. MALDEF

is particularly dedicated to securing such rights in the areas of

employment, education, immigration, political access, and

public resource equity. The question presented by this case is of

great interest to MALDEF because it implicates the availability

o f civil rights protections for Latinos in this country.

The National Asian Pacific American Legal

Consortium (the Consortium) is a national non-profit, non

partisan organization whose mission is to advance the legal and

civil rights of Asian Pacific Americans. Collectively, the

Consortium and its Affiliates, the Asian American Legal

Defense and Education Fund, the Asian Law Caucus and the

Asian Pacific American Legal Center o f Southern California,

have over 50 years of experience in providing legal services,

3a

community education and advocacy on discrimination issues.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF) is a public interest law firm founded in 1940,

dedicated to combating bias and securing equal opportunity for

all Americans through public education, antidiscrimination

legislation and full and effective enforcement of the civil rights

laws. LDF has participated as counsel of record or amicus

curiae in important cases before this Court involving

discrimination on a variety of levels, including race, Borwn v.

Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), ethnicity, St. Francis

v. Al-Khazraji, 481 U.S. 604 (1987), gender, Phillips v. Martin

Amrietta Co., 400 U.S. 542 (1971), age, McKennon v. Nashville

Banner Publishing Co., 513 U.S. 353,115 S. Ct. 4a897 (1995),

and sexual orientation, Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996),

consistently urging the Court to recognize the real and

destructive effects o f prejudice.

The National Council of Jewish Women, Inc. (NC JW)

is a volunteer organization, inspired by Jewish values, that works

through research, education, advocacy and community service

to improve the quality of life for women, children and families

and strives to ensure individual rights and freedoms for all.

Founded in 1893, the Council has 90,000 members in over 500

communities nationwide. NCJW’s National Principles state that

“Public laws, benefits and programs must be developed, enacted,

and administered and provided without discrimination on the

basis of race, gender, national origin, ethnicity, religion, age,

disability, marital status or sexual orientation.”

Founded in 1973, the National Gay and Lesbian Task

Force has worked to eliminate prejudice, violence and injustice

against gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered people at the

local, state and national level. As part of a broader social justice

4a

movement for freedom, justice and equality, NGLTF works to

create a world that respects and celebrates the diversity of human

expression and identity where all people may fully participate in

society.

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (NOW

LDEF) is a leading national non-profit civil rights organization

that performs a broad range of legal and educational services in

support ofwomen’s efforts to eliminate sex-based discrimination

and secure equal rights. NOW LDEF has frequently appeared as

counsel before this Court. See, e.g., Brzonkala v. Virginia

Polytechnic Institute, 169 F.3d 820 (4th Cir. 1999) (en banc),

cert, granted, 1999 U.S. LEXIS 4745 (U.S. Sept. 28, 1999)

(No. 99-29) (argued Jan. 11, 2000); Faragher v. City o f Boca

Raton, 118 S. Ct. 2275 (1998); Schenck v. Pro-Choice

Network, 117 S. Ct. 855 (1997); Bray v. Alexandria Women’s

Health Clinic, 113 S. Ct. 753(1993). NOW LDEF has a long

standing commitment to elimination discrimination in places of

public accommodation and has litigated extensively in this area.

See, e.g., New York State Club Ass ’n v. City o f New York, 487

U.S. 1 (1988); Board o f Directors o f Rotary Int 7 v. Rotary

Club, 481 U.S. 537 (1987); Roberts v. United States Jaycees,

468 U.S. 609 (1984).

The National Partnership for Women & Families is a

nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes fairness,

quality health care, and policies that help women and men meet

the dual demands of work and family. Since its founding in

1971 as the Women's Legal Defense Fund, the National

Partnership has participated as amicus curiae in many major

cases before this Court involving sex discrimination or

principles of discrimination law that affect sex discrimination,

including-Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984)

and Board o f Directors o f Rotary International v. Rotary Club

o f Duarte, 481 U.S. 537 (1987). Because discrimination on the

basis o f sexual orientation is intricately connected to gender-

5a

based discrimination, the National Partnership has often

participated as amicus curiae in cases asserting equal

opportunity for lesbians and gay men.

The National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) is a non

profit legal advocacy organization dedicated to the advancement

and protection o f women’s rights and the corresponding

elimination o f sex discrimination from all facets o f American

life. Since 1972, NWLC has worked to secure equal opportunity

for women in education, the workplace, and other settings,

including through litigation of cases brought under national,

state, and local antidiscrimination laws. The Center has a deep

and abiding interest in ensuring that these laws are fully

implemented and enforced.

The Northwest Women’s Law Center (NWLC) is a

non-profit public interest organization that works to advance the

legal rights o f all women through litigation, education,

legislation and the provision of legal information and referral

services. Since its founding in 1978, the NWLC has been

dedicated to protecting and securing equal rights for lesbian and

their families, and has long focused on threats to equality based

on sexual orientation. Toward that end, the NWLC has

participated as counsel and as amicus curiae in cases throughout

the Northwest, and the country and is currently involved in

numerous legislative and litigation efforts. The NWLC

continues to serve as a regional expert and leading advocate in

lesbian and gay issues.

People for the American Way Foundation (People

For) is a nonpartisan citizens’ organization established to

promote and protect civil and constitutional rights. Founded in

1980 by a group of religious, civic, and educational leaders

devoted to our nation’s heritage of tolerance, pluralism, and

liberty, People For now has more than 300,000 members

nationwide. People for has frequently represented parties and

6a

filed amicus curiae briefs in litigation seeking to defend First

Amendment freedoms, and has also been actively involved in

efforts nationwide, including litigation, to combat discrimination

and promote equal rights. People For believes society’s

compelling interest in eradicating invidious discrimination with

an organization’s First Amendment rights of free speech and

association, and has joined in filing this amicus brief in order to

urge the Court not to disturb those precedents.

Women Employed is a national membership association

of working women based in Chicago, with a membership of

2000. Since 1973, the organization has assisted thousands of

working women with problems o f sex discrimination, monitored

the performance of equal opportunity enforcement agencies,

analyzed equal opportunity policies, and developed specific,

detailed proposals for improving enforcement efforts.

The Women’s Law Project (WLP) is a non-profit

public interest legal advocacy organization located in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1974, WLP works to

abolish discrimination and injustice in our laws and institutions

and to advance the legal and economic status of women and their

families through litigation, public policy development, public

education, and individual counseling. The Law Project has

worked on both a local and national basis to eliminate

discrimination on the basis of gender and sexual orientation in

a wide variety of contexts, including employment, education,

insurance, family matters and places of public accommodations,

the area at issue in this case. WLP has a strong interest in

defending our civil rights laws from threats which seek to limit

the rights of all citizens to be free of prohibited discrimination.

7a

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers Street, N.Y. 10007—98068_(212) 619-4949

www.recordpress.com

http://www.recordpress.com