Drews v. Maryland Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Drews v. Maryland Jurisdictional Statement, 1964. 59f91b37-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9146d491-1863-4651-8e5c-ec3c3366bf05/drews-v-maryland-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

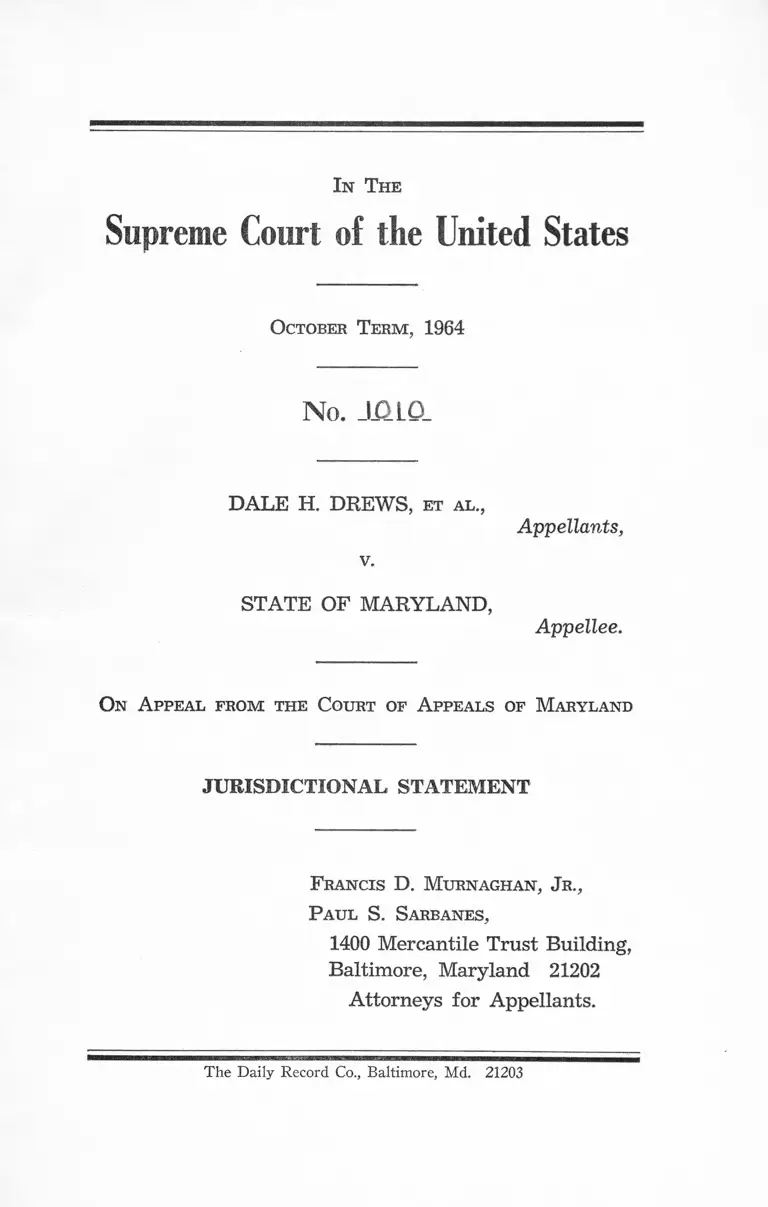

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1964

No. JOLCL

DALE H. DREWS, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Appellee.

On A ppeal from the Court of A ppeals of Maryland

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr.,

Paul S. Sarbanes,

1400 Mercantile Trust Building,

Baltimore, Maryland 21202

Attorneys for Appellants.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore, Md. 21203

I N D E X

Table of Contents

page

Opinions Below ................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

1. Proceedings below ............................................... 2

2. Basis of Jurisdiction of this Court..................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved 3

Questions Presented........................................................ 3

Statement of the Ca s e .................................................... 5

How the Federal Questions are Presented............... 8

The Federal Questions are Substantial:

1. The arrest and conviction of the appellants are

the use of State action to enforce private dis

crimination, and, therefore, constitute viola

tions of the right of the appellants under the

Fourteenth Amendment .................................... 9

2. The arrest and conviction of the appellants are

the denial of the rights of the appellants to

freedom of speech and freedom of assembly .... 14

3. The arrest and conviction of the appellants

without any evidence that the appellants acted

in any way in a disorderly manner to the dis

turbance of the public peace are a denial of

the rights of the appellants under the Four

teenth Amendment ............................................. 15

4. The arrest and conviction of the appellants for

disorderly conduct in face of the failure of the

State to arrest and convict members of the

crowd who' were actually engaged in disorderly

conduct are a denial to the appellants of equal

protection of the laws ....................................... 17

PAGE

5. The singling out of appellants for prosecution

and conviction while the State has proceeded to

discontinue and dismiss prosecutions in ap

proximately 200 other cases arising out of

demonstrations at the same place of public re

sort or amusement is a denial to appellants of

due process and equal protection of the laws

under the Fourteenth Amendment ................... 17

6. The Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

241, requires the abatement of the pending con

victions and the dismissal of the prosecutions

of the appellants.................................................. 18

Conclusion ................................................................... 21

A ppendix A — Opinion of the Court of Appeals of

Maryland on Remand from the Supreme Court

of the United States (October 22, 1964) .............. la

A ppendix B — Opinion of the Court of Appeals of

Maryland (January 18, 1961) ............................ 6a

A ppendix C — Memorandum Opinion of the Circuit

Court for Baltimore County, Maryland (May 6,

1960) ...................................................................... 13a

A ppendix D — Relevant Constitutional and Statu

tory Provisions...................................................... 19a

Table of Citations

Cases

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964) .......... 16

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ................. 10

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964) ................. 2, 7, 14, 19

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ................. 10

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ........................ 11,12

Drews v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 547 (1964) ..................... 3

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963) ...... 16

Frank v. Maryland, 359 U.S. 360 (1959) ..................... 3

ii

PAGE

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961) ................. 16

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) ..................... 10

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130 (1964) ...................2, 7,19

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) ................. 9,19

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S.

241 (1964) ............................................................. 14

Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776 (1964) ...... 16

Hillsborough v. Cromwell, 326 U.S. 620 (1946) ...... 18

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955) ...... 10

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) .......... 14

Louisville & N. R. Co. v. United States, 282 U.S. 740

(1931) ..................................................................... 17

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946) ..................... 14,15

Maryland v. Baltimore & O. R. Co., 3 How. 534 (1845) 19

Massey v. United States, 291 U.S. 608 (1934) .......... 19

McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203 (1948) 3

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ............. 3,16

Niemotko v. State, 194 Md. 247, 71 A. 2d 9 (1950) 17

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1882) ....................... 17

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .....................10,13,22

Snowden v. Snowden, 1 Bland (Md. Chan.) 550

(1829) .................................................................... 17

State v. Brown,.... D el......., 195 A. 2d 379 (1963) 10

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533

(1959) .................................................................... 10

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154 (1962) ................. 16

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) ................. 15,16

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960) 16

United States v. Chambers, 291 U.S. 217 (1934) ...... 19

United States v. Reisinger, 128 U.S. 398 (1888) ...... 19

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103 (1801) 19

United States v. Tynen, 11 Wall 88 (1870) ............. 19

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 (1963) 16

Yeaton v. United States, 5 Cranch 281 (1809) .......... 19

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ................. 18

Ill

IV

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes

PAGE

Article 27, Section 123, Annotated Code of Maryland

(1957 edition) ........................................................ 2, 3, 7

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ....................................3, 5, 9,18,19,

20, 21, 22

Civil Rights Act of 1875 ............................................... 11

Constitution of the United States:

Amendment 1 ........................................................ 3

Amendment XIV ................................3, 4, 5, 8, 9,10,11,

13,15, 17, 18

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257 (2) .......... 3

Miscellaneous

deTocqueville, Democracy in America (Oxford

University Press, 1947) ....................................... 13

In T he

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1964

No.

DALE H. DREWS, et al.,

v.

Appellants,

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Appellee.

O n A ppeal from the Court of A ppeals of Maryland

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the decision of the Court of Ap

peals of Maryland entered on October 22, 1964, reinstating

and reaffirming judgments of the Circuit Court for Balti

more County, Maryland, which had previously been af

firmed by the Court of Appeals of Maryland on January 18,

1961 and vacated by the Supreme Court of the United States

on June 22, 1964, and submit this Statement to show that

the Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdiction

of the appeal and that a substantial federal question is

presented.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals of Maryland setting

forth the decision and judgment from which this appeal is

2

taken and the dissenting opinion of Judge Oppenheimer

are reported in 236 Md. 349, 204 A. 2d 64, and are attached

hereto as Appendix A. The earlier opinion of the Court of

Appeals of Maryland which was reviewed by the Supreme

Court of the United States (378 U.S. 547) is reported in

224 Md. 186, 167 A. 2d 341, and is attached hereto as Appen

dix B. The memorandum opinion of the Circuit Court for

Baltimore County, Maryland, setting out the judgments of

conviction now on appeal is unreported and is attached

hereto as Appendix C.

JURISDICTION

1. This prosecution was begun by the filing of a criminal

information by the State’s Attorney for Baltimore County,

Maryland, against the appellants under Section 123 of

Article 27 of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edi

tion). Appellants were convicted of the charge of acting

in a disorderly manner to the disturbance of the public

peace on May 6, 1960 by the Circuit Court for Baltimore

County, Maryland. The decision of the Court of Appeals

of Maryland affirming the convictions was filed on January

18, 1961; that judgment was subsequently vacated by the

Supreme Court of the United States on June 22, 1964 and

the case remanded to the Court of Appeals of Maryland

for consideration in light of Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S.

130, and Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226. The decision of the

Court of Appeals of Maryland reinstating and reaffirming

the judgment previously entered by it was filed on October

22,1964. Notice of appeal in this case was filed on January 20,

1965 in the Circuit Court for Baltimore County, Maryland,

to which the record in the case had been returned after the

entry of judgment by the Court of Appeals of Maryland.

2. The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United

States to review this decision by direct appeal is conferred

3

by Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(2). Appel

lants question the validity of Section 123 of Article 27 of

the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition) as inter

preted by the Court of Appeals of Maryland in its decisions

of January 18, 1961 and October 22, 1964, on the ground

that, as so interpreted, it is repugnant to the Constitution

and laws of the United States, and the decision of the high

est court of the State was in favor of its validity as so

interpreted. The following cases sustain the jurisdiction of

the Supreme Court of the United States to review the de

cision of the Court of Appeals of Maryland on direct appeal.

Drews v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 547 (1964); Frank v. Mary

land, 359 U.S. 360 (1959); Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S.

268 (1951); McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S. 203

(1948).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The relevant portions of Amendments I and XIV to the

Constitution of the United States, Section 123 of Article 27

of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition), and

Title II of the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241,

are set forth in Appendix D hereto.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Appellants, two white males, one white female and one

Negro female, were convicted of violating a statute making

it a criminal offense to act in a disorderly manner to the

disturbance of the public peace at any place of public

resort or amusement. The basis for the convictions was

the refusal of the appellants to leave a public amusement

park, owned by a private corporation. The Negro appellant

and another Negro were asked to leave the park because

the owner had a policy of not admitting Negroes. The

white persons were requested to leave because they were

4

in the same group as the two Negroes. The appellants at

all times acted in a courteous and peaceful manner, and

their only conduct which was found to be disorderly was

their refusal to leave the amusement park when requested.

Under these circumstances were the appellants:

1. Denied their rights under the privileges and immuni

ties, equal protection and due process clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States

in that they were arrested and convicted, upon the request

of a private owner, under a statute which was interpreted

by the highest court of the State to make a criminal offense

the refusal to leave a place of public resort and amusement

when the request to leave was based solely on the ground

that the presence of the appellants conflicted with the

owner’s policy that members of the Negro race should be

excluded;

2. Denied their rights under the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment in that they were arrested and

convicted for exercising their rights to freedom of expres

sion and association;

3. Denied their rights under the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment in that they

were arrested and convicted without any evidence that the

appellants acted in a disorderly manner to the disturbance

of the public peace;

4. Denied their rights under the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment in that they were arrested

and convicted of acting in a disorderly manner to the dis

turbance of the public peace although the evidence clearly

showed that others were the only persons acting in a dis

orderly manner and such other persons were not proceeded

against by the State;

5

5. Denied their rights under the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment in that they

have been convicted for acts arising out of sit-in demonstra

tions at a place of public resort or amusement, whereas the

State’s Attorney of Baltimore County is proceeding to dis

continue and dismiss the prosecutions in approximately

200 other cases arising out of such demonstrations at the

same place of public resort or amusement;

6. Exercising rights now established, protected and con

firmed by the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241,

thereby requiring the abatement of the pending convictions

and dismissal of the prosecutions of appellants.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On Sunday, September 6, 1959, the appellants, three

whites and one Negro, together with another Negro, went

to Gwynn Oak Park, a public amusement park in Balti

more County, Maryland owned by a private corporation.

All Nations Day was being celebrated at the park on that

particular day (R. 33-34, E. 15)d About 3:00 P.M. the five

individuals were standing approximately in the center of

the park. They were in a group by themselves and had

attracted no attention from others present on the park

premises (R. 34, 36, E. 15, 17). A private park guard ap

proached them and told them that the park was closed to

colored persons and that they would have to leave (R. 19,

35, E. 7, 16). There was no evidence that appellants had

prior knowledge of such an exclusionary policy (See p.

14a, Appendix C). The initial direction to leave was given

to the two Negroes. When they remained, all five persons

were asked to leave, but they refused (R. 22, E. 9). Appel-

1 “ R .” references are to the transcript of testimony at the trial.

“ E.” references are to the Record Extract printed as part of appel

lants’ brief in the Court of Appeals in the initial appeal.

6

lants were very polite to the guard; one stated that he was

enjoying himself and was going to stay and look around a

little bit more (R. 22-23, E. 8, 9). Although the park was

crowded (R. 48, E. 23), there was no particular congrega

tion around the appellants until they were approached and

asked to leave by the park guard (R. 33-36, E. 15-17),

Upon the refusal of the appellants to leave the park, the

guard summoned the Baltimore County police (R. 23, E.

8). After requesting the appellants to leave (R. 35. 40-42,

E. 16, 19, 20), the police arrested the appellants on the

specific request of a park official (R. 43, 49-50, E. 20, 24).

The park official ordered the arrest in furtherance of the

amusement park’s policy of excluding Negroes (R. 19-22,

49-51, E. 7, 8, 24). During the period between the time the

appellants were first requested to leave by the park police

and their arrest by the County police, a crowd gathered

around the appellants and the police, and its members ap

peared to become angry and engaged in certain unruly and

disorderly activities, including spitting at and kicking the

appellants and using improper language in speaking to

them (R. 23-24, 26, 28, E. 9, 11, 12). There was no attempt

by the park officials or by the County police to exclude

from the park or to arrest any of those who engaged in the

disorderly conduct (R. 37, 51, 67, E. 17, 24, 33).

When arrested, appellants locked arms (R. 43, E. 20).

Appellants Drews and Sheehan, in a further show of pas

sive resistance, proceeded to lie on the ground at which

time the joining of arms with the other two appellants

ceased (R. 38, 45, 51, 54, E. 17, 21, 22, 26). Appellants

Joyner and Brown left the park in the custody of the police

but under their own power (R. 46, 53, E. 22, 26). The others

were carried out (R. 38, E. 18). None of the appellants

offered positive resistance and they made no remarks other

than a plea by Drews for forgiveness of someone who was

7

mistreating him (R. 26, 29, 47, 61, 63, E. 11, 13, 22, 30, 31).

The appellants were then taken to a police station where an

employee of the park swore out a warrant against them.

On April 5, 1960, the appellants were charged in an

amended criminal information with “acting in a disorderly

manner, to the disturbance of the public peace, in or on

Gwynn Oak Amusement Park, Inc., a body corporate, a

place of public resort and amusement in Baltimore County”

contrary to Section 123 of Article 27 of the Annotated Code

of Maryland (1957 edition). On April 8, 1960, appellants

were arraigned, pleaded not guilty and waived a jury trial.

The trial then took place on this same day. At the trial,

the officer who arrested the appellants testified that, had

it not been for the request of the park official that appel

lants be arrested, he would not have arrested them (R. 52,

E. 25). At the conclusion of the State’s case, appellants

moved for a directed verdict, which motion was taken

under advisement by the Court. On May 6, 1960, the Court

denied appellants’ motion for a directed verdict. Appel

lants introduced no testimony and renewed their motion

for a directed verdict. The Court thereupon entered a ver

dict of guilty against each of the appellants and imposed a

sentence of $25.00 plus costs on each. On June 2, 1960, an

appeal to the Court of Appeals of Maryland was filed. On

January 18, 1961, the Court of Appeals of Maryland af

firmed the judgments rendered against the appellants and

a notice of appeal to the Supreme Court of the United

States was filed with the Court of Appeals on February 13,

1961. On June 22, 1964 the Supreme Court vacated the

judgment and remanded the case to the Court of Appeals

of Maryland for consideration in light of Griffin v. Mary

land, 378 U.S. 130 and Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226. Fol

lowing such consideration the Court of Appeals of Mary

land on October 22, 1964 reinstated and reaffirmed the prior

8

judgment of conviction. Appellants filed a notice of appeal

from this decision on January 20, 1965.

HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS

ARE PRESENTED

The first four questions set out above for review in this

Court were raised in the Court of first instance, the Cir

cuit Court for Baltimore County, Maryland, generally by

pleas of not guilty entered on April 8, 1960. On the same

day at the end of the presentation of the State’s evidence,

the appellants requested a directed verdict of not guilty

on the grounds, inter alia, that, if appellants were con

victed, they would be denied their constitutional rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States. These contentions were originally made

in oral argument. A reference to the record cannot be made

since there is no transcript of the oral arguments. In the

memorandum filed by appellants in support of their motion

for a directed verdict of not guilty, each of the constitu

tional arguments raised by the first four questions pre

sented here for review were advanced and argued. How

ever, the Circuit Court judge, in his memorandum opin

ion, did not specifically pass on any of these constitutional

arguments. The same constitutional contentions were pre

sented to the Court of Appeals of Maryland in appellants’

brief and in oral argument. That Court ruled on Question

One on pages lla-12a of Appendix B, Question No. 3 on

pages 9a-10a, Questions Nos. 2 and 4 were not specifically

ruled upon by the Court of Appeals but were rejected by

the affirmance of the judgments of the Circuit Court.

The fifth question set out above for review by this Court

grew out of occurrences subsequent to conviction of Ap

pellants, and the original affirmance of their convictions by

the Court of Appeals of Maryland. The question was raised

9

in the brief of appellants in the Court of Appeals following

remand of this case by the Supreme Court. The Court of

Appeals ruled on this question on page 5a of Appendix A.

The sixth question presented for review by this Court

concerns the effect of the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964

upon the convictions of appellants. The convictions in this

case, their original affirmance by the Court of Appeals of

Maryland, and the remand of the case by this Court all

took place prior to the enactment of the Federal Civil

Rights Act of 1964. The order of the Court of Appeals set

ting the case for rehearing specified that it should be in

accordance with the remand and consequently matters

arising from the enactment of the Federal Civil Rights Act

of 1964 have not heretofore been considered in this pro

ceeding. Appellants respectfully submit that the matters

raised by question six are properly before this court for

review. Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964).

THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

1. The arrest and conviction of the appellants are the use

of State action to enforce private discrimination, and,

therefore, constitute violations of the rights of the ap

pellants under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The State of Maryland, by the decision in this case, has

made the act of refusing to leave an amusement park open

to the public but owned by a private corporation, when the

request to leave arises solely from the policy of the park

owner to exclude Negroes, a criminal offense. This case

raises therefore the important constitutional question of

whether a state can, without violating the Fourteenth

Amendment, support by the use of its criminal laws, poli

cies of racial discrimination adopted by owners of places

of public resort or amusement. Alternatively stated, has

the State of Maryland complied with the duty imposed on

10

it by the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce equal treat

ment of all persons similarly situated in a place of public

resort or amusement?

It has of course long been the law that a state cannot,

under the Fourteenth Amendment, adopt and enforce a

policy of racial segregation directly through the use of its

criminal laws. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917);

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955) ; Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956); State Athletic Commission v.

Dorsey, 359 U.S. 533 (1959). Moreover, as Shelley v. Krae-

mer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249

(1953) clearly indicate, the thrust of the Fourteenth

Amendment has not been limited solely to those laws or

state actions which enforce racial segregation policies di

rectly adopted or supported by the state. In those cases,

judicial enforcement of a discriminatory policy based upon

a private agreement was held to be state action and hence

within the prohibition set forth in the Fourteenth Amend

ment. These decisions have been read to mean that a State

may not apply its criminal trespass laws to compel a Negro

patron to leave a place of public accommodation since this

would be to place the weight of State power behind the

discriminatory action of the owner or proprietor. As the

Supreme Court of Delaware noted in State v. Brown, ....

Del...... , 195 A. 2d 379, 386 (1963).

“In the instant case, the trespass statute, as applied,

results in judicial sanction of a policy of racial dis

crimination. Therefore, just as the State, in Turner

[Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 (1962)] may

not enact a statute which supports racial discrimina

tion, the courts may not apply a statute which results

in the fostering of racial discrimination. Therefore, the

argument advanced in such cases as [citations omitted],

that a trespass prosecution is merely a neutral frame

work for a vindication of a private property right is

11

untenable. The State, by intervening on the side of

private discrimination, cannot be considered to be

acting in a neutral or indifferent manner.”

Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, it has

never, we submit, been the law that the owner of a place

of business open to the public has the right to discriminate

on the basis of race. When, in the Civil Rights Cases, 109

U.S. 3 (1883), the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was held uncon

stitutional, to the extent that it sought to regulate private

action, this Court held only that the refusal to any persons

of the accommodations of an inn, public conveyance or

place of public amusement by an individual without any

sanction or support from any state law or regulation did

not violate the Fourteenth Amendment, because the Four

teenth Amendment relates only to state action. The Civil

Rights Cases further decided that the Thirteenth Amend

ment did not sustain the Act since the private discrimina

tion, even though unlawful, did not amount to slavery or

involuntary servitude. The Court said, 109 U.S. at p. 24:

“Now, conceding, for the sake of the argument, that

the admission to an inn, a public conveyance, or a

place of public amusement, on equal terms with all

other citizens, is the right of every man and all classes

of men, is it any more than one of those rights which

the states by the Fourteenth Amendment are forbidden

to deny to any person? And is the Constitution vio

lated until the denial of the right has some State sanc

tion or authority? Can the act of a mere individual, the

owner of the inn, the public conveyance or place of

amusement, refusing the accommodation, be justly

regarded as imposing any badge of slavery or servitude

upon the applicant, or only as inflicting an ordinary

civil injury, properly cognizable by the laws of the

State, and presumably subject to redress by those laws

until the contrary appears?

“After giving to these questions all the consideration

which their importance demands, we are forced to the

12

conclusion that such an act of refusal has nothing to

do with slavery or involuntary servitude, and that if

it is violative of any right of the party, his redress is

to be sought under the laws of the State; or if those

laws are adverse to his rights and do not protect him,

his remedy will be found in the corrective legislation

which Congress has adopted, or may adopt, for counter

acting the effect of State laws, or State action, pro

hibited by the Fourteenth Amendment . .

This Court, thus, did not hold that the owner of an inn,

public conveyance or place of public amusement had a

constitutional right to discriminate on the basis of race.

On the contrary, this Court assumed that there was a

right in all citizens to frequent such places without dis

crimination on grounds of race or color. See also 109 U.S.

at pp. 19, 21, 23, and Justice Harlan’s dissent, 109 U.S.

at 41-43. This Court merely held that the Federal Govern

ment was without power to impose sanctions for violation

of the federally created right against the private persons

who were the owners of such places of business. Several

of the states have remedied the situation in which Federal

law creates a right, which is, nevertheless, imperiled by

lack of an adequate remedy, through the passage of civil

rights acts patterned on the Federal statute. That Mary

land did not have such a civil rights act at the time of the

events with which we are here concerned meant no more

than that the federally created right not to be discriminated

against in a place of public amusement did not have, in

Maryland, adequate enforcement machinery against purely

private discrimination.2 This did not mean, however, that

the owner of a place of public amusement had a right to

discriminate. A fortiori, it did not mean that he could call

_ 2 Accustomed as we now are to enforcement of federally created

rights by direct federal action, we should not lose sight of the fact

that such a technique for a federal government marked a great inno-

13

on the State of Maryland for aid in discriminating. As was

said in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, 334 U.S. at 22:

“It would appear beyond question that the power of

the State to create and enforce property interests must

be exercised within the boundaries defined by the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

For a state to create and enforce a “right” of an owner of

a business open to the public to discriminate on the basis

of race would be state action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment, and, therefore, subject to the re

strictions of that amendment. And even though it be as

sumed that the owner of purely private property has a

constitutional right to the enjoyment of his property with

out interference from others, it must be remembered that

the property here involved has been thrown open to public

use. The statute under which appellants were convicted

required an express determination that the amusement

vation when adopted in 1789. As that acute observer of the American

political system, Alexis deTocqueville, pointed out with respect to

the Constitution:

“ This Constitution, which may at first sight be confounded

with the Federal constitutions which preceded it, rests upon a

novel theory, which may be considered as a great invention in

modern political science. In all the confederations which had

been formed before the American Constitution of 1789 the allied

States agreed to obey the injunctions of a Federal Government;

but they reserved to themselves the right of ordaining and en

forcing the execution of the laws of the Union. The American

States which combined in 1789 agreed that the Federal Govern

ment should not only dictate the laws but that it should execute

its own enactments. In both cases the right is the same, but

the exercise of the right is different; and this alteration pro

duced the most momentous consequences.” deTocqueville, D e

mocracy in America (Oxford University Press, 1947), pages

88-89.

Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment represented a return, in

one limited instance, to the earlier general practice of committing

enforcement of a federally created right to the several states. That

a state might fail in its obligation to enforce such a right does not

create a “ right” in those who thereupon flaunt the federal right.

14

park was a place of public resort or amusement. The effect

of the conduct by the owner of a business open to the public

must be considered. This Court in Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U.S. 501, 506 (1946), pointed out that:

“Ownership does not always mean absolute domin

ion. The more the owner, for his advantage, opens

up his property for use by the public in general, the

more do his rights become circumscribed by the statu

tory and constitutional rights of those who use it . .

It is apparent, therefore, that the basic premises of the

Maryland Court of Appeals in the instant case concern

ing the supposed rights of the owner of a business to dis

criminate on the basis of race — and to seek state assistance

in such discrimination — have never been supported by

this Court.

This issue was the subject under discussion in the con

curring and dissenting opinions of members of this Court

in Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 242, 286, 318 (1964). The

views expressed in that case on this issue were reaffirmed

in the various concurring opinions of members of this Court

in Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379 U.S.

241 (1964) and Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964).

Appellants respectfully submit that the constitutional issue

raised by this question is not only of substantial merit but

also of great national importance meriting therefore plen

ary consideration by this Court with briefs on the merits

and oral argument. 2

2. The arrest and conviction of the appellants are the denial

of the rights of the appellants to freedom of speech

and freedom of assembly.

The attendance of the white and Negro appellants to

gether at a celebration named “All Nations Day” was more

than merely an attempt to enjoy a public amusement park.

15

Their very association together symbolized the idea ex

pressed by an “All Nations Day” celebration. They were,

therefore, exercising their rights of freedom of speech and

freedom of association, and the arrest and conviction of the

appellants for disorderly conduct for exercising these rights

is in contravention of the Fourteenth Amendment. If the

appellants were, when arrested, carrying signs proclaiming

the idea expressed by their association together, they would

clearly be protected from arrest and conviction by the in

terpretation given the Fourteenth Amendment in Marsh

v. Alabama, supra, and in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S.

1 (1949). Yet no placard could have expressed with greater

eloquence the point of view which appellants displayed by

appearing together in public despite their difference in

color. The effect of the Marsh decision is that, where a

private property owner invites the general public onto his

property for his own benefit, the owner relinquishes his

right to exclude members of the public at will where their

activities are peaceful and in furtherance of the rights of

freedom of speech and assembly. In the instant case, the

owner of the amusement park, by admitting members of

the public at large (except for Negroes) relinquished his

right to exclude the appellants while they, by their very

act of associating together, exercised the right of free

speech to advocate the breaking down of artificial barriers

based upon race. 3

3. The arrest and conviction of the appellants without any

evidence that the appellants acted in any way in a dis

orderly manner to the disturbance of the public peace

are a denial of the rights of the appellants under the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The record in this case is clear that appellants, prior to

their arrest for acting in a disorderly manner, did no more

than politely refuse to leave a public amusement park when

16

asked to leave as a result of the owner’s policy to exclude

Negroes. Appellants did nothing that was in any way dis

orderly and the hostile crowd did not assemble until after

the park officials themselves had created a scene by calling

attention to the appellants and by seeking to put the

owner’s discriminatory policy into effect.

To allow individuals who have behaved in a peaceful

manner to be convicted of acting in a disorderly manner

because of the effect of their peaceful conduct on a crowd

of hostile onlookers would make a mockery of our con

cepts of criminal conduct. One is reminded of the hapless

soul who, upon being strangled, is told by his assailant that

unless he removes his neck from the assailant’s hands, the

assailant will not be responsible for the consequences.

Their convictions clearly run counter to the decision in

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964), where this

Court was reluctant to assume that a State breach-of-peace

statute would be applicable in view of the frequent occa

sions on which the Court had reversed under the Four

teenth Amendment convictions of peaceful individuals who

were convicted of breach of the peace because of the acts

of hostile onlookers. Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 U.S.

776 (1964); Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 (1963); Ed

wards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963); Taylor v.

Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154 (1962); Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U.S. 157 (1961); Terminiello v. Chicago, supra.

It is clear from the record here that there is no evidence

of disorderly conduct on the part of appellants. The con

victions should therefore not stand. Barr v. City of Colum

bia, supra; Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199

(1960). Cf. Niemotko v. Maryland, supra, which upset a

conviction under the same criminal statute here involved.

There the defendants’ actions were taken in the face of

17

police orders and threats of arrest if the orders were dis

obeyed. See Niemotko v. State, 194 Md. 247, 250, 71 A. 2d

9, 10 (1950).

4. The arrest and conviction of the appellants for dis

orderly conduct in face of the failure of the State to

arrest and convict members of the crowd who were

actually engaged in disorderly conduct are a denial to

the appellants of equal protection of the laws.

The evidence clearly shows that the members of the

crowd which surrounded the appellants and the police

actually engaged in the only disorderly conduct which took

place. The crowd spat, kicked and used improper language.

The appellants were polite and mannerly at all times.

Neither the park owner nor the police made any attempt

to quell the disorder or to arrest any of the members of the

crowd engaged in such conduct. The arrest and conviction

of the appellants under such circumstances denied appel

lants equal protection of the law. Pace v. Alabama, 106

U.S. 583 (1882). 5

5. The singling out of appellants for prosecution and con

viction while the State has proceeded to discontinue and

dismiss prosecutions in approximately 200 other cases

arising out of demonstrations at the same place of pub

lic resort or amusement is a denial to appellants of due

process and equal protection of the laws under the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The manner in which a law is enforced may render an

otherwise constitutionally valid measure invalid. While a

statute may not be rendered ineffective solely through

non-use, e.g., Louisville & N. R. Co. v. United States, 282

U.S. 740, 759 (1931); Snowden v. Snowden, 1 Bland (Md.

Chan.) 550, 556-58 (1829), it may not be applied discrim-

18

inatorily to members of the same class. The Fourteenth

Amendment prevents the unequal enforcement of valid

laws as well as any enforcement of invalid laws. Yick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886). See also Hillsborough v.

Cromwell, 326 U.S. 620, 623 (1946), and the cases cited

therein.

Gwynn Oak Park, the scene of the alleged offenses of

appellants, was the subject of a number of sit-in demon

strations in the summer of 1963. The demonstrations

achieved their objective, for the park abandoned its seg

regation policy. In the course of the demonstrations ap

proximately 200 arrests were made. The State’s Attorney

of Baltimore County has done nothing about bringing these

other cases on for trial, and has proceeded to discontinue

and dismiss said prosecutions. Considerations of due pro

cess and equal protection under the Fourteenth Amend

ment should prohibit the continuation of the convictions

of Appellants. 6

6. The Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, re

quires the abatement of the pending convictions and

the dismissal of the prosecutions of the appellants.

Appellants were convicted in the Circuit Court for Bal

timore County, Maryland on May 6, 1960, and those con

victions were originally affirmed by the Court of Appeals

of Maryland on January 18, 1961. Both the convictions and

the affirmance took place well prior to the enactment of

the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 which was signed into

law on July 2, 1964. The case was, however, on appeal to

this Court or on remand to the Maryland Court of Appeals

throughout the intervening period.

On June 22, 1964, this Honorable Court vacated the judg

ment entered by the Court of Appeals of Maryland on Jan

uary 18,1961 and remanded the case to the Court of Appeals

19

for consideration in light of Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S.

130 and Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226. On July 31, 1964,

the Court of Appeals ordered the case set for hearing upon

the matters to be considered in accordance with the remand.

In view of the terms of the remand and the order of the

Court of Appeals, matters arising from the enactment of

the Federal Civil Rights Act have not heretofore been con

sidered in this proceeding.

However, it is clear that the judgments in this case are

not yet final, Bell v. Maryland, supra, and that these con

victions which are now on direct review must abate since

the conduct in question is rendered no longer unlawful by

the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S.

306 (1964). As Chief Justice Hughes noted in United States

v. Chambers, 291 U.S. 217, 226 (1934):

“Prosecution for crimes is but an application or en

forcement of the law, and if the prosecution continues

the law must continue to vivify it.”

See also United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103

(1801); Yeaton v. United States, 5 Cranch 281 (1809);

Maryland v. Baltimore & O. R. Co., 3 How. 534 (1845);

United States v. Tynen, 11 Wall. 88 (1870); United States

v. Reisinger, 128 U.S. 398 (1888); Massey v. United States,

291 U.S. 608 (1934).

Appellants assert that there are a number of incontro

vertible facts establishing that the Gwynn Oak public

amusement park is covered by the Federal Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241:

1. The operations of the cafeteria on the premises of the

amusement park (a cafeteria being an establishment de

scribed in paragraph (2) of section 201(b) of the Act)

affect commerce in that a substantial portion of the food

20

which it serves has moved in commerce (as provided in

Sec. 201(c)(2)).

Given that the cafeteria is a covered establishment, the

amusement park is also covered under the provisions of

Sec. 201(b) (4) and (c)(4) since there is physically located

within the premises of the amusement park a covered

establishment, the cafeteria, and since the amusement park

holds itself out as serving the patrons of such covered

establishment.

2. The amusement park is a covered establishment since

it is an “other place of exhibition or entertainment” re

ferred to in Sec. 201(b) (3) and its operations affect com

merce since it customarily presents performances, exhi

bitions, or other sources of entertainment which move in

commerce as provided in Sec. 201(c)(3) of the Act.

Alternatively, if the view is taken that the amusement

park is not a covered establishment as indicated above be

cause the operations discussed do not affect commerce, it

is asserted that it nevertheless would have been a covered

establishment at the time of the events with which we are

here concerned on the following grounds:

1. Discrimination or segregation by the cafeteria was

supported by State action (as provided in Section 201(b)

and (d ) ) since such discrimination or segregation was car

ried on under color of a custom or usage required or en

forced by officials of the State or political subdivision

thereof. In this case, the discriminatory custom or usage

was enforced by the police officers of Baltimore County,

Maryland and by the courts of the State of Maryland.

Since state action enforced discrimination by the cafe

teria, thereby making it a covered establishment, the

amusement park was also a covered establishment since

21

there was physically located within its premises a covered

establishment and since it held itself out as serving the

patrons of said covered establishment (as provided in Sec.

201(b)(4)).

2. The amusement park itself was an “other place of ex

hibition or entertainment” under Section 201(b) (3) of the

Act and was a place of public accommodation thereunder

since discrimination or segregation by it was supported by

State action.

Said discrimination or segregation by the amusement park

was supported by State action within the meaning of the

Act in that such discrimination or segregation was carried

on under color of a custom or usage required or enforced by

officials of the State or a political subdivision thereof (as

provided by Sec. 201(d)).

CONCLUSION

It is submitted that the decisions of the Court of Appeals

of Maryland fail to recognize the limitations imposed by

the Fourteenth Amendment upon the State’s power 1) to

enforce discrimination in places of public resort or amuse

ment through the use of its criminal laws; 2) to punish,

through the use of its criminal laws, exercises of the right

to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly; 3) to con

vict a person for a violation of a criminal statute without

any evidence of the substantial elements of the crime; 4)

to arrest and convict a person of violation of a criminal

statute when the evidence clearly shows that others were

the only persons in violation of said statute and such per

sons were not proceeded against in any way; 5) to prose

cute and convict a person under the criminal laws for acts

arising out of sit-in demonstrations when prosecutions in

approximately 200 other cases arising out of such demon

22

strations at the same place of public resort or amusement

are being discontinued and dismissed; and 6) that said deci

sions fail to give due consideration to the effect upon the

prosecutions and pending convictions of the appellants of

the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

We believe that the questions presented by this appeal

are substantial and are of public importance. As this Court

noted in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 22 (1948):

“The problem of defining the scope of the restric

tions which the Federal Constitution imposes upon

exertions of power by the States has given rise to many

of the most persistent and fundamental issues which

this Court has been called upon to consider.”

Respectfully submitted,

Francis D. Murnaghan, Jr.,

Paul S. Sarbanes,

1400 Mercantile Trust Building,

Baltimore, Maryland 21202

Attorneys for Appellants.

la

APPENDIX A

Opinion of Court of A ppeals of Maryland on Remand

from the Supreme Court of the United States

(Decided October 22,1964)

236 Md, 349, 204 A. 2d 64

Horney, J. (Dissenting Opinion by Oppenheimer, J.)—

The appellants were convicted in 1960 of violating Code

(1957), Art. 27, § 123, by “acting in a disorderly manner to

the disturbance of the public peace” in a place of “public

resort or amusement.” On the appeal to this Court, the

convictions were affirmed in Drews v. State, 224 Md. 186,

167 A. 2d 341 (1961). Having found that Gwynn Oak

Amusement Park in Baltimore County was a place of public

resort or amusement within the meaning of the statute, we

held that the conduct of the appellants — two of whom

were white men, one a white woman, and the other a

colored woman — during the course of a demonstration

protesting the segregation policy of the park, by joining

arms and dropping to the ground after they had refused to

obey a lawful request to leave the privately owned park,

was disorderly in that it “disturbed the public peace and

incited a crowd.” We also held that the action taken by the

county police, in arresting the appellants for disorderly

conduct (after the police at the request of the park man

ager had asked them to leave and again they refused), did

not constitute state enforcement of racial discrimination in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States. A direct appeal was thereafter taken to the Su

preme Court of the United States, which, in a per curiam

filed June 22, 1964, in Drews v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 547, va

cated the judgments and remanded the case to this Court

“for consideration in light of Griffin v. Maryland [378 U.S.

130] and Bell v. Maryland [378 U.S. 226],” decided on the

same day as Drews.

In Griffin v. State, 225 Md. 422, 171 A. 2d 717 (1961),

where the park officer was authorized to make arrests

2a

either as a paid employee of a detective agency then under

contract to protect and enforce the racial segregation policy

of the operator of Glen Echo Amusement Park in Mont

gomery County or as a nonsalaried special deputy sheriff

of the county, we affirmed the conviction of the appellants

for trespassing on private property in violation of Code

(1957), Art. 27, § 577, when they refused to leave the prem

ises after having been notified to do so. But the Supreme

Court in Griffin v. Maryland, supra, held that the arrest of

the appellants by the park officer was state action in that

he was possessed of state authority and purported to act

under that authority, and reversed the judgment. In Bell

v. State, 227 Md. 302, 176 A. 2d 771 (1962), where the ap

pellants had entered the private premises of a restaurant

in Baltimore City in protest against racial segregation, sat

down and refused to leave when asked to do so on the

theory that their action in remaining on the premises

amounted to a permissible verbal or symbolic protest

against the discriminatory practice of the owner, we af

firmed the convictions for criminal trespass for the reason

that the right to speak freely and to make public protest

did not import a right to invade or remain on privately

owned property so long as the owner retained the right to

choose his guests or customers. The Supreme Court granted

certiorari. In the interim between the decision of this

Court and the decision of the Supreme Court, both the city

and state enacted “public accommodation laws.” When the

Supreme Court decided Bell v. Maryland, supra, it reversed

the judgment of this Court and remanded the case for a

determination by us of the effect of the subsequently en

acted public accommodation laws on pending criminal

trespass convictions.1

On the remand of this Drews case, the appellants raise

two questions. In effect they contend: (i) that their arrest

and conviction constitutes state action in the light of the

decision in Griffin v. Maryland, supra; and (ii) that to up

hold their conviction now for acts arising out of sit-in dem

(1 ) See Bell v. State, 236 Md. 356, 204 A. 2d 54 (1964), decided

on the remand on or about the same time as this case.

3a

onstrations at Gwynn Oak Amusement Park would be to

deny them due process and equal protection because the

State’s Attorney for Baltimore County has failed to prose

cute approximately two hundred other cases charging the

same offense.

(i)

In reconsidering the convictions of the “Drews” appel

lants in the light of Griffin v. Maryland, supra, we find

nothing therein which compels or requires a reversal of our

decision in Drews v. State (224 Md. 186). Significantly, the

question as to whether the same result would have been

reached by the Supreme Court had the arrests in Griffin

been made by a regular police officer, as in the Drews case,

was not decided. The arrests and subsequent convictions of

the appellants for criminal trespass were held in Griffin

to constitute state action because the arresting officer, a

park employee, was also a special deputy sheriff. In Drews,

however, the appellants not only refused to leave the

amusement park peacefully after they had been requested

to do so, but acted in a disorderly manner when the arrest

ing officers, who were county police officers, not park em

ployees, undertook to eject them. The record in Drews

does not show, nor has it ever been contended, that the

park employee, who assisted the arresting officers, had

power (as was the case in Griffin) to make arrests. By

reversing Griffin and remanding Drews, the Supreme

Court must have had some doubt as to whether the two

cases were distinguishable. We think there are important

differences in the two cases between the reasons or causes

for the arrests and the type of police personnel that made

the arrests, and that such distinctions are controlling.

In Drews, where the trespassers conducted themselves

in a disorderly manner when the police undertook to for

cibly eject them from the amusement park in an effort to

prevent them from further inciting the gathering crowd by

remaining in the park after they had been requested to

leave by the park manager as well as the county police,

the arrests were made by policemen who were not em

ployed by the park, who were not paid by the park, and

4a

who were under no orders of any park official. The very

fact that the police made no move to eject the trespasser

from the park until they were requested to do so by the

manager shows the complete absence of any cooperative

state action. Nor was there any evidence that the State

desired or intended to maintain the amusement park as

a segregated place of amusement. In these circumstances,

it seems clear to us that the arrest of the Drews appellants

(who were both white and colored) for disorderly con

duct did not constitute state enforcement of racial dis

crimination. To hold otherwise would, we think, not only

deny the park owners equal protection of the laws, but

could seriously hamper the power of the State to maintain

peace and order and, when imminent as was the case here,

to forestall mob violence or riots.

We deem it unnecessary to elaborately discuss the only

two cases cited by the appellants — State v. Brown, 195

A. 2d 379 (Del. 1963), and Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284

(1963). Neither is apposite here and, assuming they are,

both are clearly distinguishable on the facts. Even if the

arrest of the Drews appellants for disorderly conduct was

the result of or arose out of their ejection from the park

for trespassing on private property, there was no violation

of a constitutional guarantee. We reiterate what was re

cently said in In Matter of Cromwell, 232 Md. 409, 413. 194

A. 2d 88 (1963), that “we find no violation of the Four

teenth Amendment in the assertion of a private proprietor’s

right to choose his customers, or to eject those who are dis

orderly.” We see no reason to reverse the convictions in

this case.

The reason for the remand of the case for consideration

in the light of Bell v. Maryland, supra, is not clear. The

judgments in Bell were vacated and the case remanded to

enable this Court to pass upon the effect of supervening

public accommodation laws on the criminal trespass law.

Since there is no provision in the public accommodation

law enacted by the State (Code, 1964 Supp., Art. 49B, § 11)

with respect to amusement parks, we need not decide the

effect of the supervening legislative enactment on the

convictions in this case.

5a

(ii)

The second contention of the appellants — that the fail

ure of the State to prosecute others for the same or similar

offenses is a denial of due process or equal protection — is

without merit and has no bearing on the convictions in this

case. Guilt or innocence cannot be made to depend on the

question of whether other parties have not been prosecuted

for similar acts. Callan v. State, 156 Md. 459, 466, 144 Atl.

350 (1929). Nor is the exercise of some selectivity in the

enforcement of a criminal statute, absent a showing of un

justifiable discrimination, violative of constitutional guar

antees. Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962). See also Moss

v. Hornig, 314 F. 2d 89 (C.A. 2d 1963).

Judgments reinstated and reaffirmed; appellants to pay

the costs.

Oppenheimer, J. (dissenting)—

In Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130 (1964), the Supreme

Court of the United States reversed the judgments against

the defendants affirmed by us in Griffin v. State, 225 Md.

422, 171 A. 2d 717 (1961) on the ground that the arrests

were the products of State action taken because the de

fendants were Negroes, and therefore racial discrimination

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment. In Griffin, the arresting officer, Collins,

was a deputy sheriff of Montgomery County employed by

and subject to the direction and control of the amusement

park. The record shows that in this case the special police

man, Officer Wood, was in the employ of the amusement

park but it does not show whether or not he had been

deputized by Baltimore County. Pursuant to the instruc

tions of the park’s management, Wood told the defendants

the park was closed to Negroes, ordered them to leave and,

when they did not, sent for the Baltimore County police.

He and the county police together removed the defendants

from the park.

If Wood, the “special officer” in this case, had virtually

the same authority from Baltimore County that Collins had

6a

from Montgomery County, it seems to me immaterial that

he called in the Baltimore County police to help him evict

the defendants. He was the proximate cause of the arrests.

If his authority stemmed from the State, then under Griffin

v. Maryland, supra, the State was a joint participant in the

discriminatory action.

On the facts, it also seems immaterial that the convictions

here were for disorderly conduct rather than for trespass

as in Griffin. In resisting the command of the officers to

leave the park, the defendants used no force against the

officers or anyone else; they held back or fell to the ground.

Such failure to obey the command, if the command itself

was violative of the Constitution, would not sustain the

convictions. Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284, 291, 292

(1963).

The Baltimore County Code authorizes the county to ap

point special police officers to serve for private persons or

corporations. Baltimore County Code, Sections 24-13 and

35-3 (1958). I would remand this case to the Circuit Court

for Baltimore County for the taking of additional testimony

to determine whether or not Wood was appointed by Bal

timore County under these sections of its Code. If he was,

the convictions should be reversed.

APPENDIX B

Opinion of Court of A ppeals of Maryland

(Decided January 18,1961)

224 Md. 186,167 A. 2d 341

Hammond, J.:

The four appellants were convicted by the court sitting

without a jury of violating Code (1957), Art. 27, Sec. 123,

by “acting in a disorderly manner to the disturbance of

the public peace” in a “place of public resort or amuse

ment.” Two of appellants are white men, one is a white

woman, and the other a Negress. Accompanied by a

Negro who was not tried, they had gone as a group to

7a

Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Baltimore County, which

as a business policy does not admit Negroes, and were

arrested when they refused to leave after being asked to

do so.

Appellants claim that there was no evidence that the

Park is a place of public resort or amusement, that if

there were such evidence the systematic exclusion of

Negroes prevents the Park from being regarded as such

a public place, that they were not guilty of disorderly

conduct and, finally, if the Park is a place of public resort

or amusement their presence there was in the exercise

of a constitutional right, and their arrest and prosecution

amounted to State action to enforce segregation in violation

of the Constitution of the United States.

There is no direct statement in the record that the Park

is a place of public resort or amusement but we think the

evidence clearly permitted the finding the trial court made

that it is. There was testimony which showed, or permitted

the inference, that the Park is owned by a private corpora

tion, that it has been in operation each summer for many

years, that among its attractions are a miniature golf course

and a cafeteria, that appellants’ conduct occurred on “All

Nations Day” which usually attracts a large crowd, that on

that day the Park was so crowded there was but elbow

room to walk, and that the Park’s policy was to welcome

everyone but Negroes. The trial court properly could have

concluded the Park is a place resorted to by the general

public for amusement. Cf. Iozzi v. State, 224 Md. 42.

A lawmaking body is presumed by the Courts to have

used words in a statute to convey the meaning ordinarily

attributed to them. In recognition of this plain precept

the Courts, in construing zoning, licensing, tax and anti-

discrimination statutes, have held that the term place of

public resort or amusement included dance halls, swim

ming pools, bowling alleys, miniature golf courses, roller

skating rinks and a dancing pavilion in an amusement

park (because it was an integral part of the amusement

park), saying that amusement may be derived from

participation as well as observation. Amos v. Prom, Inc.,

8a

117 F. Supp. 615; Askew v. Parker (Cal. App.), 312 P. 2d

342; Jaffarian v. Building Com’r (Mass.), 175 N.E. 641;

Jones v. Broadway R,oller Rink Co. (Wis.), 118 N.W. 170,

171; Johnson v. Auburn & Syracuse Electric R. Co. (N.Y.),

119 N.E. 72. Section 123 of Art. 27 proscribes conduct

which disturbs the public peace at a place where a number

of people are likely to congregate, whether it is on gov

ernmental property or on property privately owned. This

is made clear by the prohibition of offensive conduct not

only on any public street or highway but in any store

during business hours, and in any elevator, lobby or cor

ridor of an office building or apartment house having more

than three dwelling units, as well as in any place of public

worship or any place of public resort or amusement. We

read the statute as including an amusement park in the

category of a place of public resort or amusement.

We find no substance in the somewhat bootstrap argu

ment that the regular exclusion of Negroes from the Park

kept it from being within the ambit of the statute. Early

in the common law the duty to serve the public without

discrimination apparently was imposed on many callings.

Later this duty was confined to exceptional callings, as

to which an urgent public need called for its continuance,

such as innkeepers and common carriers. Operators of

most enterprises, including places of amusement, did not

and do not have any such common law obligation, and in

the absence of a statute forbidding discrimination, can

pick and choose their patrons for any reason they decide

upon, including the color of their skin. Early and recent

authorities on the point are collected, and exhaustively

discussed, in the opinion of the Supreme Court of New

Jersey in Garifine v. Monmouth Park Jockey Club, 148 A.

2d 1. See also Greenfeld v. Maryland Jockey Club, 190 Md.

96; Good Citizens Community Protective Assoc, v. Board

of Liquor License Commissoners, 217 Md. 129, 131; Slack

v. Atlantic White Tower System, Inc., 181 F. Supp. 124;

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845.

It has been noted in the cases that places of public ac

commodation, resort or amusement properly can exclude

would-be patrons on the grounds of improper dress or

9a

uncleanliness, Amos v. Prom, Inc., supra (at page 629 of

117 F. Supp.); because they are under a certain age, are

men or are women, or are unescorted women, Collister

v. Hayman (N.Y.), 76 N.E. 20; or because for some other

reason they are undesirables in the eyes of the establish

ment. Greenfeld v. Maryland Jockey Club; Good Citizens

Protective Assoc, v. Board of Liquor License Commis

sioners; Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, Inc., all

supra. See 86 C.J.S. Theaters and Shows Secs. 31 and 34

to 36. We have found no decision holding that a policy

of excluding certain limited kinds or classes of people

prevents an enterprise from being a public resort or amuse

ment, and can see no sound reason why it should.

Appellants’ argument that they were not disorderly is

that neither the mere infringement of the rules of a pri

vate establishment nor a simple polite trespass constitutes

either a breach of the peace or disorderly conduct. We

find here more than either of these, enough to have per

mitted the trier of fact to have determined as he did that

the conduct of appellants was disorderly.

It is said that there was no common law crime of dis

orderly conduct. Nevertheless, it was a crime at common

law to do many of the things that constitute disorderly

conduct under present day statutes, such as making loud

noises so as to disturb the peace of the neighborhood, col

lecting a crowd in a public place by means of loud or

unseemly noises or language, or disturbing a meeting as

sembled for religious worship or any other lawful purpose.

Hochheimer on Crimes and Criminal Procedure, Sec. 392

(2nd Ed.); 1 Bishop on Criminal Law, Sec. 542 (9th Ed.);

Campbell v. The Commonwealth, 59 Pa. St. Rep. 266.

The gist of the crime of disorderly conduct under Sec.

123 of Art. 27, as it was in the cases of common law

predecessor crimes, is the doing or saying, or both, of that

which offends, disturbs, incites, or tends to incite, a num

ber of people gathered in the same area. 3 Underhill,

Criminal Evidence, Sec. 850 (5th Ed.), adopts as one defini

tion of the crime the statement that it is conduct “of such

a nature as to affect the peace and quiet of persons who

10a

may witness the same and who may be disturbed or pro

voked to resentment thereby.” Also, it has been held that

failure to obey a policeman’s command to move on when

not to do so may endanger the public peace, amounts to

disorderly conduct. Bennett v. City of Dalton (Ga. App.),

25 S.E. 2d 726, appeal dismissed, 320 U.S. 712, 88 L. Ed.

418. In People v. Galpern (N.Y.), 181 N.E. 572, 574, it was

said, under a New York statute making it unlawful to con

gregate with others on a public street and refuse to move

on when ordered by the police, that refusal to obey an

order of a police officer, not exceeding his authority, to

move on “even though conscientious — may interfere with

the public order and lead to a breach of the peace,” and

that such a refusal “can be justified only where the cir

cumstances show conclusively that the police officer’s di

rection was purely arbitrary and was not calculated in any

way to promote the public order.” See also In re Neal, 164

N.Y.S. 2d 549 (where the refusal of a school girl to leave

a school bus when ordered to do so by the authorities was

held to be disorderly conduct, largely because of its effect

on the other children); Underhill, in the passage cited

above, concludes that “failure to obey a lawful order of

the police, however, such as an order to move on, may

amount to disorderly conduct.” See also People v. Nixon

(N.Y.), 161 N.E. 463; 27 C.J.S. Disorderly Conduct, Sec.

1(4) f; annotation 65 A.L.R. 2d 1152; compare People v.

Carcel (N.Y.), 144 N.E. 2d 81; and People v. Arko, 199

N.Y.S. 402.

Appellants refused to leave the Park although requested

to do so many times. A large crowd gathered around them

and the Park employee who was making the requests,

and seemed to “mill in and close in” so that the employee

sent for the Baltimore County police. The police, at the

express direction of the manager of the Park, asked the

appellants to leave and again they refused, even when

told they would be arrested if they did not. Admittedly

they were then deliberately trespassing. That they in

tended to continue to trespass until they were forcibly

ejected is made evident by their conduct when told they

were under arrest. The five joined arms as a symbol of

11a

united defiance and then two of the men dropped to the

ground. Two of the appellants had to be carried from

the Park, the other three had to be pushed and shoved

through the crowd. The effect of the appellants’ behavior

on the crowd is shown by the testimony that its mem

bers spit and kicked and shouted threats and imprecations,

and that the Park employees feared a mob scene was about

to erupt. The conduct of appellants in refusing to obey

a lawful request to leave private property disturbed the

public peace and incited a crowd. This was enough to

sustain the verdict reached by Judge Menchine.

We turn to appellants’ argument that the arrest by the

County police constituted State action to enforce a policy

of segregation in violation of the ban of the Equal Protec

tion and Due Process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

against State-imposed racial discrimination. The Supreme

Court said in the racial covenant case of Shelley v. Krae-

mer, 334 U.S. 1, 13, 92 L. Ed. 1161, 1180: “The action in

hibited by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment

is only such action as may fairly be said to be that of the

States. That Amendment erects no shield against merely

private conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful” .

The Park had a legal right to maintain a business policy of

excluding Negroes. This was a private policy which the

State neither required nor assisted by legislation or admin

istrative practice. The arrest of appellants was not because

the State desired or intended to maintain the Park as a

segregated place of amusement; it was because the appel

lants were inciting the crowd by refusing to obey valid

commands to move from a place where they had no lawful

right to be. Both white and colored people acted in a dis

orderly manner and the State, without discrimination,

arrested and prosecuted all who were so acting.

While there can be little doubt that the Park could

have used its own employees to eject appellants after they

refused to leave, if it had attempted to do so there would

have been real danger the crowd would explode into riotous

action. As Judge Thomsen said in Griffin v. Collins, 187 F.

Supp. 149, 153, in denying a preliminary injunction and

12a

a summary judgment in a suit brought to end the segre

gation policy of the Glen Echo Amusement Park near

Washington: “Plaintiffs have cited no authority holding

that in the ordinary case, where the proprietor of a store,

restaurant, or amusement park, himself or through his

own employees, notifies the Negro of the policy and orders

him to leave the premises, the calling in of a peace officer

to enforce the proprietor’s admitted right would amount

to deprivation by the state of any rights, privileges or

immunities secured to the Negro by the Constitution or

laws. Granted the right of the proprietor to choose his

customers and to eject trespassers, it can hardly be the

law, as plaintiffs contend, that the proprietor may use

such force as he and his employees possess but may not

call on a peace officer to enforce his rights.”

The Supreme Court has not spoken on the point since

Judge Thomsen’s opinion. The issue was squarely pre

sented for decision in Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454,

5 L. Ed. 2d 206, but the Court chose to decide the case on

the basis that the conviction of a Negro for unlawfully

remaining in a segregated bus terminal restaurant vio

lated the Interstate Commerce Act, which uses broad

language to forbid a carrier from discriminating against

a passenger. In the absence of controlling authority to

the contrary, it is our opinion that the arresting and con

victing of appellants on warrants sworn out by the Park

for disorderly conduct, which resulted from the Park en

forcing its private, lawful policy of segregation, did not

constitute “such action as may fairly be said to be that of

the States.” It was at least one step removed from State

enforcement of a policy of segregation and violated no

constitutional right of appellants.

Judgments A ffirmed, W ith Costs.

13a

APPENDIX C

Memorandum Opinion of Circuit Court for

Baltimore County

(Filed May 6,1960)

Unreported

The facts of the case are not in serious dispute. On

Sunday, September 6, 1959, at the Gwynn Oak Amusement

Park, located in Baltimore County, “All Nations Day” was

being celebrated. It was a “right crowdy day * * *. There

was just more or less elbow room when you walked any

where in the park” (Tr. 48). The Park is privately owned

by a corporation, known as Gwynn Oak, Incorporated.

There is no evidence that there was any sign or signs to

indicate that any particular segment of the population

would not be welcome, so that for the purpose of this case

it is assumed by the Court that there were no such signs.

At about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, a special officer em

ployed by Gwynn Oak Park, Incorporated observed five

persons in approximately the center of the Park, near

the cafeteria and miniature golf course. This employee

approached the group, consisting of three white and two