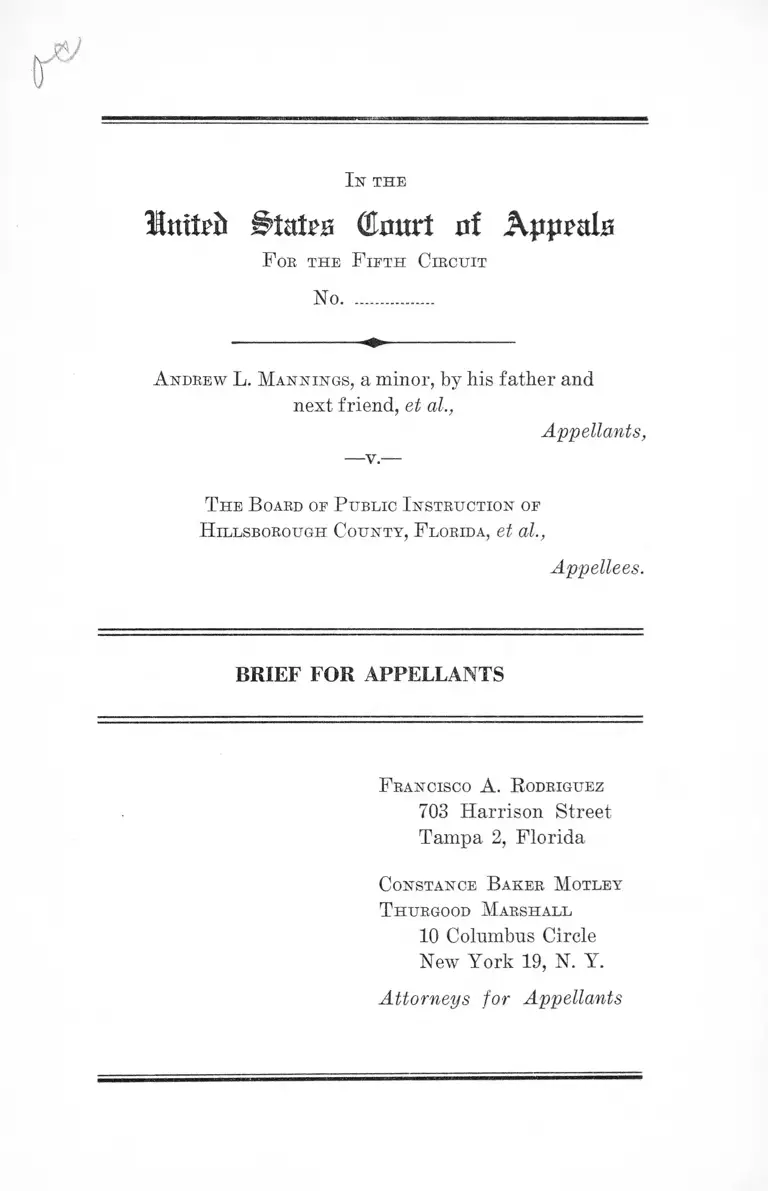

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Florida Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, Florida Brief for Appellants, 1959. 250f76e4-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/91a61eb8-313c-45e2-a0cd-f89aa40e5041/mannings-v-board-of-public-instruction-of-hillsborough-county-florida-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

)

1st th e

Itutpft GImtrt n! Appeals

F oe th e F if t h C iecuit

No....... ....... .

A ndrew L. M an n in g s , a m inor, by his fa th er and

n ext fr ien d , et al.,

Appellants,

— y .—

T h e B oard of P ublic I nstruction of

H illsborough Co u nty , F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

F rancisco A. R odriguez

703 Harrison Street

Tampa 2, Florida

Constance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

In the

HnxUb States Court of Appeals

F oe th e F if t h C iecuit

No...................

A ndbew L. M an n in g s , a m inor, by his fa th er and

next frien d , et al.,

Appellants,

— v.—

T he B oaed of P ublic I nstruction of

H illsborough C o u nty , F lorida, et al,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Tampa

Division, entered on the 7th day of August 1959 dismissing

the complaint herein on the ground that appellants have

not exhausted their administrative remedies under the

Florida Pupil Assignment Law (F. S. A., Sec. 230.232)

(E. 12).

This cause involves racial segregation in the public

elementary and high schools of Hillsborough County,

Florida.

The complaint, which was filed on the 12th day of

December 1958 invoking the jurisdiction of the court below

pursuant to the provisions of Title 28, U. S. C. §1343(3),

2

alleges that the adult plaintiffs are all Negro citizens of

the United States and of the State of Florida, residing

in the County of Hillsborough, Florida and the parents

of Negro children eligible to attend the public schools of

said county who, with the exception of one child, are

all presently enrolled in the public elementary schools

of said county. The one child who is not so enrolled will

be eligible to enroll for the first time in September 1959

(E. 3). The suit was brought by the adult plaintiffs on

behalf of their minor children as next friend and on behalf

of other parents and children similarly situated pursuant

to the provisions of Eule 23(a)(3) of the F. E. C. P.

(E. 2). The gravamen of the complaint is that “ defen

dants, acting under color of the authority vested in them

by the laws of the State of Florida, have pursued and are

presently pursuing a policy of operating the public school

system of Hillsborough County, Florida, on a racially seg

regated basis” and that in August 1955 “ the defendants

were formally petitioned by Negro parents of children

eligible to attend the public schools of Hillsborough County,

Florida, to abolish the segregation policy . . . ” (E. 4-5).

The complaint further alleges that, “ This formal petition

was followed by several letters on behalf of the Negro

parents requesting defendants to desegregate the public

schools of Hillsborough County, Florida,” and that, “De

spite this petition and despite the several letters directed

to the defendants, the defendants have refused to discon

tinue the policy of operating the public schools of Hills

borough County, Florida, on a raciallv segregated basis”

(E. 5).

In addition, the complaint alleges that pursuant to the

racial segregation policy, seventy two of the public schools

of Hillsborough County are limited to attendance by white

children only and eighteen schools are limited to attendance

3

by Negro children; that many Negro students, including

some of the minor plaintiffs, who reside nearer to schools

limited to white students, are required to attend schools

limited to Negro students which are considerably removed

from the places of their residence; and that in some in

stances plaintiffs travel as much as ten miles to attend a

Negro elementary school, whereas they reside only two

blocks from a white elementary school (E. 4-5). Finally,

the complaint alleges that defendants’ refusal to change

the policy operates to prevent Negro students from being

assigned to white schools nearer to their places of residence

which they would attend if they were white and which they

presently desire to attend (R. 5).

However, the complaint does not allege that any of the

plaintiffs or any of the members of their class have ever

applied for admission to any particular white school and

have been denied admission to same, solely because of their

race and color. Moreover, the complaint does not allege

that plaintiffs have exhausted the remedy provided by the

Florida Pupil Assignment Law (F. S. A., Sec. 230.232).

Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground,

among others, that the plaintiffs had failed to exhaust the

administrative remedy available to them under the Florida

Pupil Assignment Law (R. 7). The defendants’ motion

came on for hearing on the 7th day of August 1959 and

after the hearing the court below entered an order dismiss

ing the complaint on said ground (R. 12).

Specification of Errors

The court below erred in ruling that the complaint must

be dismissed because the appellants have not exhausted

their administrative remedy under the Florida Pupil As

signment Law.

4

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Florida Pupil Assignment Law Is Inapplicable to

This Case.

A. The appellants, by this law suit, do not seek specific

assignment to specific schools

Appellees would like to believe that the enactment of

the Florida Pupil Assignment Law operates to relieve

them of the constitutional duty imposed upon them by the

decisions of the United States Supreme Court in the School

Segregation Cases, Brown v. Board of Education of To

peka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), and Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1 (1958), to cease operation of the public school

system of Hillsborough County, Florida, on a racially

segregated basis. Appellees apparently believe that—

despite these decisions of the Supreme Court which put

upon them an affirmative duty to reorganize the public

school system under their jurisdiction on a nonracial basis

and to assign children in the newly reorganized system

without reference to race and without perpetuating the

status quo existing prior to these decisions—they may con

tinue to operate as they had prior to these decisions and

may shift their duty to change the racially segregated

pattern to the Negro community by requiring Negro parents

to seek transfers for their children to white schools within

the existing segregated system.

The original School Segregation Cases brought in fed

eral district courts which culminated in the first Brown

decision were not brought in federal district courts for the

purpose of having such courts pass upon the plaintiffs’

applications for admission to specific white schools within

5

the segregated system. Each of those cases was brought

for the purpose of having the federal courts declare uncon

stitutional state statutes and school board policies requir

ing operation of the entire school system on a racially

segregated basis and were so treated by the Supreme

Court. Those cases were all brought as class actions, dis

crimination against a class was alleged, and the Supreme

Court expressly treated the eases as class actions calling

for remedial action involving a whole class of persons dis

criminated against and not simply the individual plaintiffs.

Therefore, after holding in the first Brown decision that

state enforced racial segregation in public schools is un

constitutional, the Court set the cases down for reargument

as to the type of relief to be afforded in view of the fact that

those cases were class actions. The Court said:

Because these are class actions, because of the wide

applicability of this decision, and because of the great

variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees

in these cases presents problems of considerable com

plexity (at 495).

Clearly, then, the Supreme Court considered those cases

as being brought for the purpose of giving relief to Negroes

as a class against racial segregation in the schools and

not for the sole purpose of securing the admission of the

individual plaintiffs to particular white schools. If the

latter had been the Court’s approach to these cases, then

the Court would simply have ordered or directed the entry

of orders to the effect that the named plaintiffs be admitted

to the particular white schools to which they had applied

and no further consideration as to type of relief would

have been necessary.

In the second Brown decision the Court again made it

clear that the type of relief to be given in these cases was

6

relief for the class as a whole—relief which affects the

entire school system involved—and not simply one or two

specific schools to which plaintiffs may or may not be

assigned. There the Court said:

At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making* the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

in our May 17, 1954 decision (at 300). (Emphasis

added.)

̂ ̂ ^

To that end, the courts may consider problems re

lated to administration, arising from the physical

condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and at

tendance areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools on a

nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regula

tions which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems. They will also consider the adequacy of

any plans the defendants may propose to meet these

problems and to effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system. During this period

of transition, the courts will retain jurisdiction of these

cases (at 300-301). (Emphasis added.)

Apparently because many school authorities had taken

the view of these cases which appellees here take, the

Court in the Cooper case, supra, undertook to restate what

it had already stated in the Brown decisions regarding the

manner in which federal district courts are to approach

7

school desegregation cases and then made the following

unequivocal statement:

. . . the District Courts were directed to require

“ a prompt and reasonable start toward full compli

ance,” and to take such action as was necessary to

bring about the end of racial segregation in the public

schools “ with all deliberate speed.” Ibid. Of course,

in many locations, obedience to the duty of desegrega

tion would require the immediate general admission of

Negro children, otherwise qualified as students for the

appropriate classes, at particular schools. On the other

hand, a District Court, after analysis of the relevant

factors (which, of course, excludes hostility to racial

desegregation), might conclude that justification ex

isted for not requiring the present nonsegregated ad

mission of all qualified Negro children. In such cir

cumstances, however, the courts should scrutinize the

program of the school authorities to make sure that

they had developed arrangements pointed toward the

earliest practicable completion of desegregation, and

had taken appropriate steps to put their program into

effective operation. It was made plain that delay In

any guise in order to deny the constitutional rights

of Negro children could not be countenanced, and that

only a prompt start, diligently and earnestly pursued,

to eliminate racial segregation from the public schools

could constitute good faith compliance. State authori

ties were thus duty hound to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the elimi

nation of racial discrimination in the pubic school sys

tem (358 U. S. 1, 7). (Emphasis added.)

B. Prior application fo r admission to particular schools

is not a prerequisite to federal court jurisdiction

in school segregation cases.

In line with the decisions of the United States Supreme

Court in the cases referred to above, this court has con

sistently ruled that federal jurisdiction in school segrega

tion cases need not be predicated on an application by a

Negro child for admission to a particular white school

and denial of admission thereto by school authorities solely

because of race and color but must be predicated upon an

allegation of a policy of racial segregation in force in the

public school system involved, and relief in such cases

must be predicated upon proof of such a policy. Holland

v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach County (5th

Cir. 1958), 258 F. 2d 730; Gibson v. Board of Public In

struction of Dade County (5th Cir. 1957), 246 F. 2d 913.

See, Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education

(N. D. Ala. 1958), 162 F. Supp. 372, 375-376, aff’d 358 U. S.

101.

In the Holland case, although the infant plaintiff was

found to be ineligible for admission to the white school to

which he applied, on residential grounds, this court, never

theless, held that he had standing to sue and could invoke

the jurisdiction of the federal district court to enjoin racial

segregation in the Palm Beach County school system.

There this court said:

That the plaintiff was ineligible to attend the school

to which he applied would not, however, excuse a fail

ure to provide nonsegregated schools. It is not neces

sary to review piecemeal the district court’s findings

of fact and conclusions of law, for the record as a whole

clearly reveals the basic fact that, by whatever means

accomplished, a completely segregated public school

system was and is being maintained and enforced.

9

No doubt that fact is well known to all citizens of the

County, and the courts simply cannot blot it out of

their sight (at 732). (Emphasis added.)

Similarly, in this ease, appellees may not ask this court

or the court below to close its judicial eyes to facts which

are clear to everyone else in Hillsborough County and that

is that racial segregation is still the basis upon which the

public schools of the county are presently being operated.

Moreover, it is well settled that for the purposes of a motion

to dismiss, all of the well-pleaded facts alleged in the com

plaint are deemed admitted as a matter of law. Mitchell v.

Wright (5th Cir. 1954), 154 F. 2d 924, cert. den. 329 U. S.

733. Here the complaint clearly and succinctly alleges,

in paragraphs 6 and 7, that the defendants “ have pursued

and are presently pursuing a policy of operating the public

school system of Hillsborough County, Florida on a racially

segregated basis,” and that after formally being petitioned

to change this policy, defendants “ have refused to discon

tinue the policy.”

In the Gibson case no prior application had been made

on the part of any of the infant plaintiffs for admission to

white schools. There this court held prior application un

necessary where, as here, the plaintiffs had petitioned the

Board to change the racial segregation policy and the Board

had failed or refused to do so.

In the Shuttlesworth case the State of Alabama first re

pealed the compulsory school segregation provisions of its

law before enacting the School Placement Law and, in the

light of that fact, plaintiffs offered no proof whatsoever in

support of their allegations, denied by defendants, alleging

discrimination against plaintiffs in the enforcement of the

law but relied chiefly upon their claim that the law was

unconstitutional on its face (at 375-376, 380). Here, unlike

10

the Shuttlesworth case, proof of racial discrimination in

the operation of the public school system was offered in

support of a motion for summary judgment filed by plain

tiffs. [The depositions and affidavits on file in the court

below in support of motion for summary judgment, of

course, are not included in the record on this appeal since

the court below did not rule on that motion. In addition,

defendants had been subpoenaed to bring other documen

tary evidence in support of said motion which the court

would not receive since it granted the motion to dismiss.]

C. Neither the Florida Pupil Assignm ent Law nor any other

law can justify the continued operation o f the public

schools on a racially segregated basis.

In the Holland case, immediately following the quote set

forth above, this court pointed out that a three-judge fed

eral court had, just prior thereto, upheld the Alabama

School Placement Law as to the constitutionality of that

act on its face, alone, and proceeded to say:

Nothing said in that opinion conflicts in any way

with this Court’s earlier statement relative to the

Florida Pupil Assignment Law:

“ * # * Neither that nor any other law can justify

a violation of the Constitution of the United States

by the requirement of racial segregation in the public

schools.” Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of

Dade County, 5 Cir. 1957, 246 F. 2d 913, 914.

Here appellees, likewise, plead the Florida Pupil As

signment Law in defense of an action brought to enjoin

racial segregation in the operation of the school system,

and argued the applicability of same in the face of over

whelming proof, evidenced by depositions, affidavits and

other documentary evidence which appellees were advised

11

appellants would introduce in support of their motion for

summary judgment, set for hearing by appellants on the

same day on which appellees’ motion to dismiss was to

be heard, and in the light of common knowledge that segre

gation is still the basis of operating their school system.

D. The Florida Pupil Assignm ent Law does not provide an

adequate rem edy fo r the relief sought in this action.

The relief sought in this action is not in the nature of

a mandatory injunction requiring appellees to admit the

named appellants to certain named schools. The relief

sought is, as stated above, relief for a class discrim

inated against in the public school system as a whole. The

prayer of the complaint is that appellees be enjoined “ from

continuing to pursue the policy of operating the public

schools of Hillsborough County, Florida on a racially seg

regated basis and enjoining them from refusing to permit

the minor plaintiffs, and other minor Negro children sim

ilarly situated, to attend schools nearer their places of

residence solely because of the race and color of said minor

plaintiffs.” A policy of racial segregation says to Negroes,

as a class, you are not permitted to apply for, to be ad

mitted to, and you will not be assigned to, white schools.

Once appellees have ceased operating the school system on

a swiracial basis and have reassigned pupils on a nonracial

basis, it may be that then, and only then, that one can be

required to invoke the remedy provided by the Florida

Pupil Assignment Law for the purpose of gaining admis

sion to a particular school. In short, the remedy provided

by the Florida Pupil Assignment Law is not an adequate

remedy for securing operation of the entire school system

of Hillsborough County, Florida on a nonracial basis. It

is a remedy for securing assignment to a particular school,

only, whether within the framework of segregation or with

out that framework.

12

In both the Holland and Gibson eases this court, as

pointed out above, expressly considered the applicability

of the Florida Pupil Assignment Law to those cases and

concluded that it need not be invoked before seeking the

kind of relief sought in those cases and sought in this case,

i.e., relief against a policy of segregation in the operation

of the school system.

Similarly, the court in Kelley v. Board of Education of

City of Nashville (M. D. Tenn. 1958), 159 F. Supp. 272,

aff’d on other grounds,----- F. 2 d -------- (6th Cir.), decided

June 17, 1959, held that the Tennessee Pupil Assignment

Act did not provide an adequate remedy for the relief

sought in class actions involving school segregation. In

so holding the court there said:

. . . it must be recalled that the relief sought by the

complaint is not merely to obtain assignment to par

ticular schools, but in addition to have a system of

compulsory segregation declared unconstitutional and

an injunction granted restraining the Board of Educa

tion and other school authorities from continuing the

practice and custom of maintaining and operating the

schools of the city upon a racially discriminatory basis

(at 275). (Emphasis added.)

Likewise here, the relief sought is an injunction restrain

ing the Board, its members, and other school authorities

from continuing the policy, practice and custom of main

taining and operating the schools of the county upon a

racially discriminatory basis.

13

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the

court below must be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

F rancisco A. R odriguez

703 Harrison Street

Tampa 2, Florida

Constance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

Certificate of Service

T his is to ceetiey that on th e ....... day of August 1959

I served a copy of the foregoing brief for appellants upon

John M. Allison, P. 0. Box 1531, Tampa 1, Florida and

Morris E. White, Citizens Bldg., Tampa 2, Florida by mail

ing a true copy of same to each of them to the addresses

given herein via United States Air Mail, postage prepaid.

Constance Baker Motley