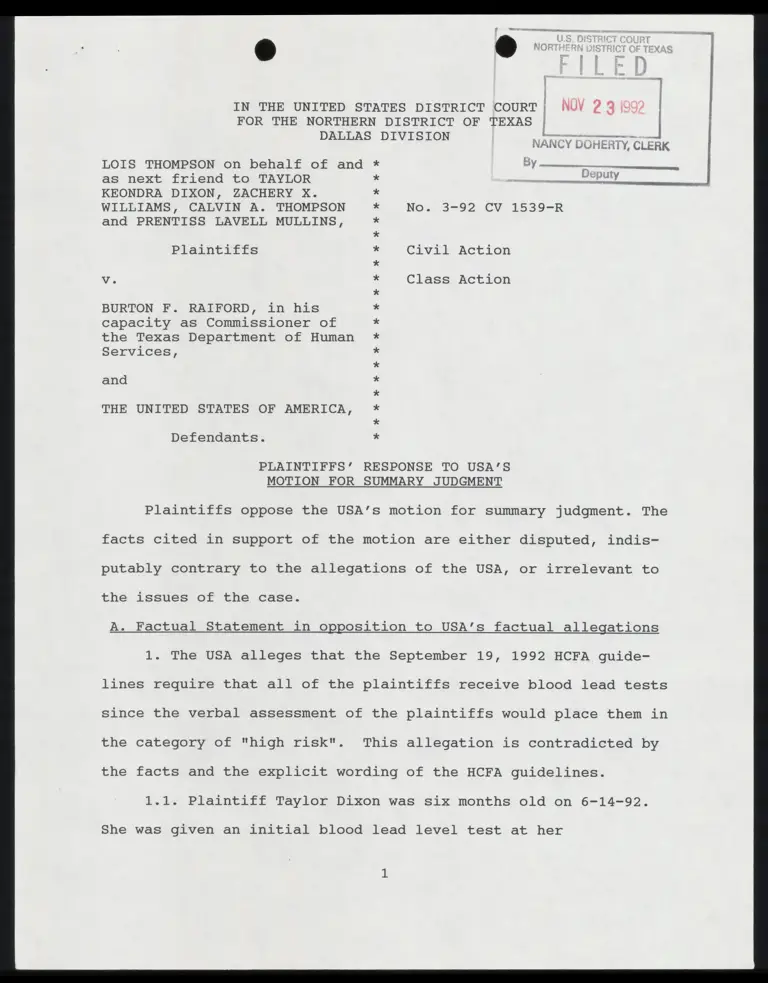

Plaintiffs' Response to USA's Motion for Summary Judgment with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1992

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Response to USA's Motion for Summary Judgment with Certificate of Service, 1992. dbec1e79-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/91b02dd2-b901-45f1-8788-8887122a7379/plaintiffs-response-to-usas-motion-for-summary-judgment-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

¥ - A.

ji

be » ; 4

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT | NUV 2 3

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS | i

DALLAS DIVISION Fe —————

NANCY DOHERTY, CLERK

BY ca ei.

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and

as next friend to TAYLOR

KEONDRA DIXON, ZACHERY X.

WILLIAMS, CALVIN A. THOMPSON

and PRENTISS LAVELL MULLINS,

No. 3-92 CV 1539-R

Plaintiffs Civil Action

Vv. Class Action

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human

Services,

and

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

¥

%

X

X

X¥

%F

X

XX

XX

¥

¥

FX

XX

X

¥

XX

X

F*

¥

¥

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS’ RESPONSE TO USA'’S

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Plaintiffs oppose the USA’s motion for summary judgment. The

facts cited in support of the motion are either disputed, indis-

putably contrary to the allegations of the USA, or irrelevant to

the issues of the case.

A. Factual Statement in opposition to USA’s factual allegations

1. The USA alleges that the September 19, 1992 HCFA guide-

lines require that all of the plaintiffs receive blood lead tests

since the verbal assessment of the plaintiffs would place them in

the category of "high risk". This allegation is contradicted by

the facts and the explicit wording of the HCFA guidelines.

1.1. Plaintiff Taylor Dixon was six months old on 6-14-92.

She was given an initial blood lead level test at her

grandmother’s request on 5-05-92. The blood lead level test

showed 9 ug/dl [Lois Thompson declaration].

1.2. The Sept. 19, 1992 HCFA guidelines for "High Risk"

children specifically states: "If the initial blood lead level

test results are less than (<) 10 micrograms per deciliter

(ug/dL), a screening EP test or blood lead test is required at

every visit prescribed in your EPSDT periodicity schedule through

72 months of age." [HCFA 9/19/92 guidelines 5132.2 c. Screening

Blood Tests. (2) High Risk]. The State of Texas can follow the

HCFA guidelines to the letter and still provide Taylor Dixon with

only an EP test for the rest of her early childhood despite her

"High Risk" status and despite the fact that blood lead levels

often peak at ages greater than 12 months [CDC 1991 page 43].

1.3 Using the HCFA guidelines, Taylor Dixon will be screened

using the admittedly ineffectual EP test during the period of her

life when the most rapid rate of increase in blood lead levels

will occur. "Blood lead concentrations increase steadily up to at

least 18 months of age. The most rapid rate of increase occurs

between 6 and 12 months of age." [CDC 1991 page 42]

1.4. The 9/19/92 HCFA guidelines and the "Action Transmit-

tal" by which the guidelines were distributed to the states are

not mandatory or otherwise binding on the states. Lieql v. Webb,

802 F.2d 623, 626 (2nd Cir. 1986) - specific discussion of HCFA

"Action Transmittals". Should the State choose to ignore or

otherwise refuse to implement the 9/19/92 HCFA guidelines, each

plaintiff will be tested for childhood lead poisoning through the

EP test. The last written expression of the State of Texas’

policy on the use of EP tests for childhood lead poisoning is in

the Donald L. Kelley, Texas State Medicaid Director, July 9, 1992

letter in response to an Open Records Act request. In response to

the request for the "number of lead blood screens performed on

children for the past five fiscal years", Kelley states "Those

with abnormal EP test results receive lead tests." [letter

attached to declaration of Laura Beshara]. The State’s October 9,

1992 answer to the Second Amended Complaint admits the allegation

in plaintiffs € 50. "Only if a child test higher than 35 on the

EP test is a blood lead level test administered."?!

1.5. The State of Texas has ignored other HCFA guidelines

related to screening for childhood lead poisoning. HCFA released

a report date July 12, 1991 that reviewed the State of Texas’

compliance with the risk assessment requirements of the Medicaid

statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r), two years after the effective date

of the statute. HCFA found "The State has not established risk

factors (other than age) to assist providers in determining

whether it is appropriate to perform a blood lead level test. It

has established an age factor...however, according to Section

5123.D.1 of the State Medicaid Manual, States should also consid-

1 Although the State’s answer to the allegation goes on to

state that the EP test will be discontinued as a blood lead level

test in November, 1992, the State has taken no official action to

so discontinue the practical use of the EP test. At least as of

the date of the answer, the official practice of the State of

Texas was to use blood lead tests only if the primary EP test

showed a high EP count. The answer was filed after the 9/19/92

effective date of the HCFA guidelines.

3

er environmental aspects when establishing risk factors" [HCFA's

Medicaid Oversight Report of the Texas EPSDT Program, July 21,

1991, attached to Beshara declaration]. Thus the State of Texas

ignored HCFA’s guidelines for a long time without suffering any

penalty.

1.6. The USA’s Hiscock Declaration recounts the USA’s re-

quirements over the years that the states conduct childhood lead

screening and treatment. The USA’s "Strategic Plan for the

Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning" U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services, February 1991 reported that "many

States do not conduct much screening or do not pay for environ-

mental investigations for poisoned children." [page 18, attached

to Beshara declaration].

1.7. The 9/19/92 HCFA guidelines contain statements which

authorize the general use of the EP test regardless of the "High

Risk" status of the child.

"States continue to have the option to use the EP test as

the initial screening blood test."

"As part of the nutritional assessment conducted at each

periodic screening, an EP blood test may be done to test for iron

deficiency. This blood test may also be used as the initial

screening blood test for lead toxicity."

2. If a parent or other adult in charge of the child does

not know the correct answer to the verbal screening questions,

eg. whether or not the living unit has lead pipes or copper with

lead solder joints, and the answer should be yes, then "High

Risk" children will be screened using the EP test [Rosen affida-

vit page 8°].

3. The USA alleges that requiring blood lead tests for all

Medicaid eligible children without regard to a priority system

will result in significant delays in providing blood lead tests

for high risk children because some states, unspecified as to

identity or number, do not have sufficient capacity to use the

blood lead level tests. For any location without inhouse capaci-

ty for blood lead testing, the current nationwide laboratory

testing services provide the capacity for the blood lead level

testing. These laboratories are available to any location with

express mail service [Nicar Declaration; Rosen affidavit pages

10-12]. There is no lack of "capacity" if HCFA is really willing

to pay for blood lead level testing for all Medicaid eligible

children.

4. The USA alleges as a fact that the continued use of the

EP test is based on the USA’s taking into account the current

advances in scientific knowledge about lead screening procedures.

This allegation is disputed by the significant sources of scien-

tific knowledge about the use of EP as a lead screening procedure

which contradict the USA’s position. One of these scientific

sources is a study and report authored in part by the USA’s

affiant, Sue Binder, MD.

4.1. Dr. Binder is an author of the article "Evaluation of

2 This is the affidavit of John F. Rosen, MD. filed with the

amicus pleadings of the interveners.

5

the erythrocyte protoporphyrin test as a screen for elevated

blood lead levels" October 1991, Journal of Pediatrics, 548-550

[copy attached to Beshara declaration]. Dr. Binder’s study

reported that the EP test was able to detect only 26% of the

children with elevated blood lead levels > 10 ug/dL [table page

549]. The report concludes "For identification of the children

with BPb levels of 10 to 24 ug/dl, another screening method,

probably BPb measurement, will be needed" [page 550].

4.2. The federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease

Registry [ATSDR] filed its "The Nature and Extent of Lead Poison-

ing in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress" in

1988. The Report analyzed the existing research on the reliabili-

ty of the EP test as a screening test for lead poisoning. "Analy-

sis of data from the second National Health and Nutrition Exami-

nation Survey (NHANES II) by Mahaffey and Annest (1986) indicates

that Pb-B levels in children can be elevated even when EP levels

are normal. Of 118 children with Pb-B levels above 30 ug/dl (the

CDC criterion level at the time of NHANES II), 47% had EP levels

at or below 30 ug/dl, and 58% (Annest and Mahaffey, 1984) had EP

levels less than the current EP cutoff value of 35 ug/dl (CDC,

1985)". HHS concluded "This means that reliance on EP level for

initial screening can result in a significant incidence of false

negatives or failures to detect toxic Pb-B levels." page II-9.

4.3. The 1991 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

"Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning"

correctly forecast the 1991 CDC actions lowering the level of

blood lead which should be taken as a symptom of lead poisoning.

"In 1991 CDC will likely issue new recommendations suggesting

that screening programs attempt to identify children with blood

lead levels below 25 ug/dL." HHS, "Strategy", 1991, page 23. The

HHS "Strategic Plan" correctly stated that the CDC action should

mean an end to the use of EP testing for childhood lead screen-

ing. "This change will mean that blood lead measurements must be

used for childhood lead screening instead of EP measurements."

HHS, "Strategy", 1991, page 23 (emphasis added) [excerpts at-

tached to Beshara declaration].

5. The USA denies that financial considerations played any

part in its decision to allow the continued use of the EP test.

Dr. Sue Binder, the USA’s affiant, states the following in her

1991 Journal of Pediatrics article: "The EP test has several

practical advantages: it is inexpensive and easy to perform, and

it can identify iron deficiency in children." [page 550].

6. The USA alleges that the HCFA guidelines are compatible

with the CDC’s 1991 position on the use of verbal questions to

determine whether a child is at high or low risk. The USA then

uses this fact to imply that the HCFA guidelines allowing the use

of the EP test for "low risk" children are also compatible with

the 1991 CDC statement. This implication is false. The CDC 1991

statement allows the use of verbal questions to determine high or

low risk only if the child is given a blood lead level test no

matter what the risk characterization.

6.1. Page 42 of the October 1991 CDC statement unequivocally

states "The questions are not a substitute for a blood lead

test." (emphasis in the original).

6.2. HCFA itself has recognized the need to confirm the

verbal screening with a blood lead test no matter what category

of risk the answers would seem to justify. "We agree that re-

sponses to questions are not a substitute for a blood lead test."

[Aug. 6, 1992 letter from Christine Nye, Director Medicaid

Bureau, to Julius Chambers, Director-Counsel NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. attached to interveners’ complaint].

7. The Federal Centers for Disease Control states "Screening

should be done using a blood lead test. Since erythrocyte proto-

porphyrin (EP) is not sensitive enough to identify more than a

small percentage of children with blood lead levels between 10

and 25 ug/dL and misses many children with blood lead levels > 25

ug/dL (McElvaine et al., 1991), measurement of blood lead levels

should replace the EP test as the primary screening method."

[CDC, "Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children", 1991, page

411-

8. The EP test does not provide an assessment of blood lead

levels that is appropriate to any age or risk.

8.1. "This change [lowering the level of blood lead levels

by CDC] will mean that blood lead measurements must be used for

childhood lead screening instead of EP measurements." HHS,

"Strategic Plan", 1991, page 23 (emphasis added). The USA's

affiant, Sue Binder, MD., is a principal author of the "Strategic

Plan". This statement that blood lead measurements "must" be used

instead of EP is at least inconsistent with the position in her

affidavit that the EP test is an effective screening test for

childhood lead poisoning.

8.2. The USA knows that the EP test is not an appropriate

lead blood level assessment for any age and risk factors. The

9/19/92 HCFA amendment acknowledges this. "The erythrocyte

protoporphyrin (EP) test is not sensitive for blood lead levels

below 25 ug/dL."

8.3. The HHS "Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Child-

hood Lead Poisoning", 1991 states "At present it is much cheaper

and easier to perform an EP test than a blood lead measurement;

however, the EP test is not a useful screening test for blood

lead levels below 25 ug/dL." [Page 40]. The USA’s affiant, Sue

Binder, MD., is a principal author of the "Strategic Plan".

8.4. The Hiscock declaration admits that the EP test does

not measure blood lead levels and that only the blood lead test

directly measures blood lead levels [Hiscock Declaration { 9.,

page 5]. The EP test measures only the level of erythrocyte

protoporphyrin in the blood [Hiscock Declaration q 9; Binder

Declaration q 14].

8.5. If the EP test is used as an assessment of blood lead

levels, only 27% of the children whose actual blood lead levels >

10 ug/dL will be identified [Binder study table page 549, at-

tached to Beshara declaration].

8.6. The EP test does not provide an assessment of blood

lead levels at any level [Rosen affidavit pages 8-9]. The EP test

discovered only 73% of the high risk children with blood lead

levels > 25 ug/dl in the Binder study area. The EP test accurate-

ly assessed only 26%, 42%, and 50% of the high risk children with

elevated lead levels in other national and local studies [Binder

study page 549, results of NHANES II overall and high risk

subset, and Oakland study, attached to Beshara declaration].

9. The new HCFA guidelines are not consistent with the CDC

1991 statement.

9.1. The new HCFA guidelines allow the use of the EP test

for the screening of children ranked "low risk" as a result of

the verbal screening. CDC 1991 states:

"The questions are not a substitute for a blood lead test"

[CDC page 42].

"If the answers to all questions are negative, the child is

at low risk for high-dose lead exposure and should be screened by

a blood lead test at 12 months and again, if possible, at 24

months (since blood lead levels often peak at ages greater than

12 months)" [CDC 1991 page 43].

9.2. The new HCFA guidelines allow the use of EP testing for

the follow up screening of high risk children whose initial blood

lead level test results in a finding < 10 ug/dl. "If the initial

blood lead test results are less than (<) 10 micrograms per

deciliter (ug/dL), a screening EP test or blood lead test is

required at every visit prescribed in your EPSDT periodicity

schedule through 72 months of age." [HCFA 5123.2.D.c(2) High

Risk]. CDC 1991 requires all subsequent screening to be done

10

using the blood lead test [CDC 1991 page 44].

10. Nothing in the new HCFA guidelines restricts the permis-

sion to use the EP test to states which do not have the "capaci-

ty" to administer blood lead tests.

B. Issues on which discovery is needed

1. The USA alleges several facts surrounding the process by

which the new HCFA guidelines were developed. Plaintiffs believe

that these facts are irrelevant to the issues before the Court.

The USA’s allegations involve allegations of input and consulta-

tion that plaintiffs have no ready access to or means of confirm-

ing. The USA’s facts on consultation and input are completely

within the control of the federal agencies involved. It is

unlikely that any federal employee would even be willing to give

an affidavit which did not corroborate the USA’s position. The

USA’s motion was filed while plaintiffs are prohibited from

obtaining merits discovery by the Local Rules. If the Court

believes these allegations are relevant, plaintiffs request that

the Court either refuse the application or order a continuance

for plaintiffs to conduct discovery on these allegations.

2. The USA alleges that there is a lack of "capacity" in

some unspecified states which lack supports the continued use of

the EP test. The USA furnishes no single specific instance of a

state without the capacity. The facts upon which the USA relies

are completely within the control of the USA. There has not been

enough time to even attempt to obtain affidavits from each of the

50 states on the issue of capacity. Affidavits are not likely to

12

be a good source of reliable evidence since each state will have

a vested financial interest in at least understating its capacity

for administration of blood lead tests. Plaintiffs have not been

able to do any discovery on this issue because of the stage of

the case and the Local Rule prohibiting merits discovery while

the class motion is pending. While plaintiffs believe that the

declarations of Rosen and Nicar put into dispute the factual

issue of "capacity", plaintiffs request the Court to either

refuse the application for judgment or order a continuance and

allow plaintiffs the opportunity to conduct discovery on the

USA’s lack of capacity allegations.

3. The USA makes the factual allegation that the federal

Centers for Disease Control [CDC], as an agency, believes that

the new HCFA guidelines are consistent with the CDC’s 1991

Statement. The only factual support for the allegation is the

single statement by Sue Binder, MD., and employee of CDC. Dr.

Binder is not the head of CDC and her statement does not set out

the authority she has to make such a statement on behalf of the

agency. Given that CDC is an agency of the USA, it is unlikely

that plaintiffs will be able to obtain voluntary and candid

affidavits setting out the facts underlying Dr. Binder’s state-

ment from other federal employees. Given the explicit contradic-

tions between major parts of the HCFA guidelines and the CDC 1991

Statement on the use of the EP test, discovery of documents and

depositions of witnesses are necessary to develop the issue of

CDC's position on the issue. Plaintiffs have not been able to do

12

such discovery because of the stage of the case and the Local

Rule prohibiting merits discovery until the class questions are

resolved. Plaintiffs request the Court to either refuse the

application for judgment or order a continuance to allow plain-

tiffs the opportunity to conduct discovery on the issue.

C. Issues of law

1. Do plaintiffs have standing to bring this suit?

2. Does the USA’s continued support for and financing of the

states’ use of the EP test as a screening test for childhood lead

poisoning in the Medicaid/EPSDT program violate the provisions of

the Medicaid Act, 42 U.S.C. §1396d4(r)>?

D. Conclusion

Plaintiffs have met their burden to show that, based on the

factual evidence, the USA is not entitled to summary judgment.

Each of the critical fact issues upon which the USA relies has

been met by credible evidence in either the declarations of Rosen

and Nicar or in the written statements of federal agencies or

employees such as Dr. Binder. The motion should be denied.

13

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL M. DANIEL, P.C.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226-1637

(214) 939-9230 (telephone)

(214) 939-9229 (facsimile)

sp NEL Bi of

Michael M. Daniel

State Bar No. 05360500

By Xana A Ae iusa

“Tah ra B. Beshara

State Bar No. 02261750

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a true and correct copy of the above document

was served upon counsel for defendant by being placed in the U.S.

Mail, first class postage prepaid, on the XQ 3{£ day of

oem, 1992.

Se ura A. 2en/ a

i ra B. Beshara

14

¥

550 McElvaine et al.

of iron deficiency in the Chicago children (a largely minor-

ity, inner-city population) may have been higher than in the

NHANES II children (a representative sample of U.S.

children); unfortunately, in this study, no data were avail-

able to assess the iron status of the Chicago children.

These data indicate that the EP test performed accept-

ably as a screening test for BPb levels =25 ug/dl in the

high-risk Chicago population but that when the definition

of an elevated BPb level was lowered to =15 ug/dl, the

sensitivity of the EP test decreased to 37%. This decrease

makes it a less useful screening test for BPb levels in the 10

to 24 ug/dl range.

The EP test has several practical advantages: it is inex-

pensive and easy to perform, and it can identify iron defi-

ciency in children.’ The sensitivity of the EP test is also good

for identifying children with very high BPb levels, those who

most urgently need follow-up. For identification of the chil-

dren with BPb levels of 10 to 24 ug/dl, another screening

method, probably BPb measurement, will be needed. Such

screening would be facilitated by the development of

cheaper, easier-to-use, portable instruments for measuring

BPb lead levels accurately at the new, lower levels of con-

cern.

Information on the Childhood Lead Screening Program was

provided by Charles R. Catania, City of Chicago Department of

Health. Thomas D. Matte, MD, and Jeffrey J. Sacks, MD, of the

Centers for Disease Control, provided valuable editorial assistance

in the preparation of this manuscript. The NHANES 11 data tapes

were supplied by the National Center for Health Statistics. Data

management was assisted by Mary Boyd, of CDC, and Nance Du-

laj, of the City of Chicago Department of Health Laboratory.

¢

The Journal of Pediatrics

October 1991

REFERENCES

I. Centers for Disease Control. Preventing lead poisoning in

young children: a statement by the Centers for Disease Con-

trol. CDC Report No. 99-2230. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services, 1985.

2. Agency for Toxic Substances and Discase Registry. The nature

and extent of lead poisoning in children in the United States:

a report to Congress. Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services, 1988.

3. California Department of Health Services. Childhood lead

- poisoning in California, extent, causes and prevention: report

to the California State Legislature. Sacramento, Calif.: State

of California Health and Welfare Agency, 1991.

4. Mushak P, Davis JM, Crocetti AF, Grant LD. Prenatal and

postnatal effects of low-level lead exposure: integrated sum-

mary of a report to the U.S. Congress on childhood lead poi-

soning. Environ Res 1989;50:11-36.

5. Piomelli S, Seaman C, Zullow D, Curran A, Davidow B.

Threshold for lead damage to heme synthesis in urban children.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982;79:3335-9.

6. Hammond PB, Bornschein RL, Succop P. Dose-cffect and

dose-response relationships of blood lead to erythrocytic pro-

toporphyrin in young children. Environ Res 1985;38:187-96.

7. Lamola AA, Joselow M, Yamane T. Zinc protoporphyrin

(ZPP): a simple, sensitive, fluorometric screening test for lead

poisoning. Clin Chem 1975:;21:93-7.

8. Blanksma L. Lead: atomic absorption method. In: Levinson

SA, MacFate RP, eds. Clinical laboratory diagnosis. Philadel-

phia: Lea & Febiger 1969:461-4.

9. Mahaffey KR, Annest JL. Association of erythrocyte proto-

porphyrin with blood lead level and iron status in the Second

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1976—

1980. Environ Res 1986:;41:327-38.

10. Marcus AH, Schwartz J. Dose-response curves for erythrocyte

protoporphyrin vs blood lead: cffects of iron status. Environ

Res 1987;44:221-7.