Robinson v Shell Oil Company Reply Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1995

30 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robinson v Shell Oil Company Reply Brief for Petitioner, 1995. a8abfda4-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/91b1b0d6-415c-49ad-8947-b5b0604d096e/robinson-v-shell-oil-company-reply-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

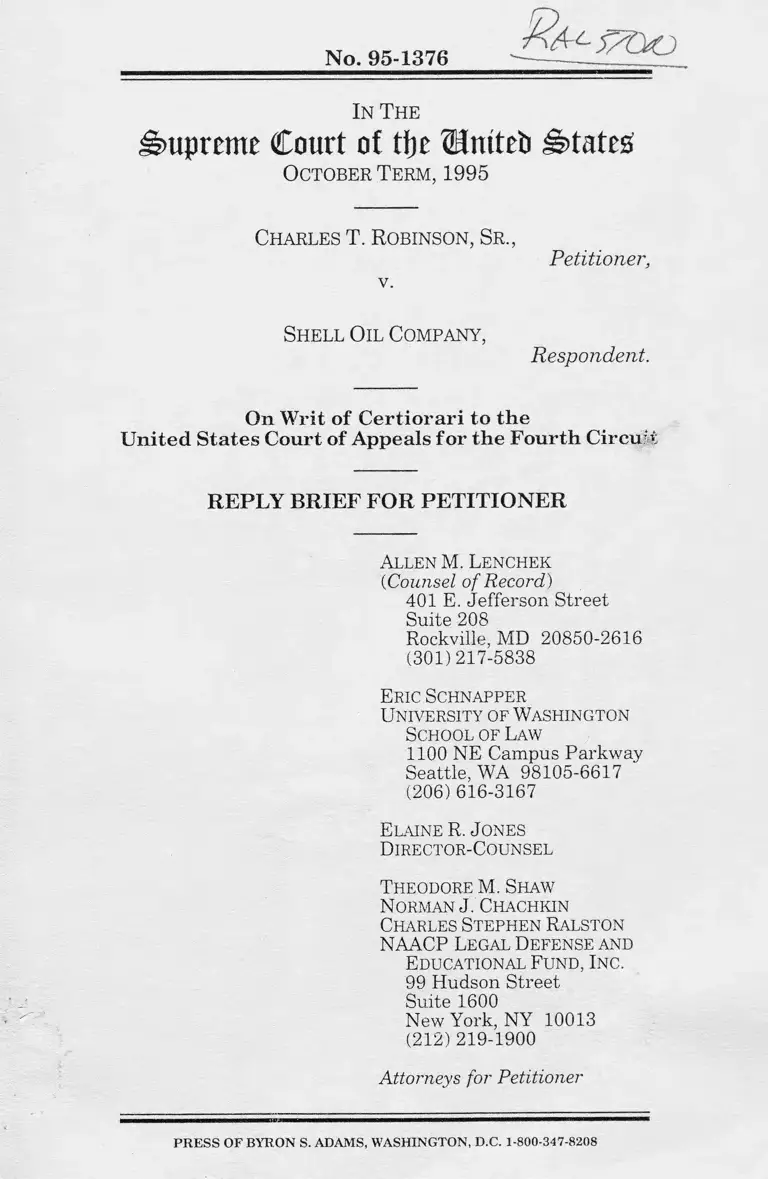

N o. 95-1376 f\M-S70*o

In T he

Supreme Court of tftc Mntteb States

October T erm , 1995

Charles T. R obinson , Sr .,

Petitioner,

v.

Shell Oil Company,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

AllenM. Lenchek

(Counsel of Record)

401 E. Jefferson Street

Suite 208

Rockville, MD 20850-2616

(301)217-5838

Eric Schnapper

University of Washington

School of Law

1100 NE Campus Parkway

Seattle, WA 98105-6617 '

(206) 616-3167

Elaine R. J ones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212)219-1900

Attorneys for Petitioner

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In troduction ........................ ................................................. 1

I. The Statutory Language . ..................... .............. 2

II. The Availability of State Remedies ................. 10

III. The Workability of Applying Section 704

to Former Employees ..................................... .. 15

Conclusion 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . 16

Bagwell v. Peninsula Regional Medical Center, 665 A.2d

297 (Md. App. 1995) .............................................. 12

Bailey v. USX Corp., 850 F. 2d 1506 (11th Cir. 1988) . 17

Franks v. Bowman Trans. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) . . . 16

Harris v. Forklift Sys., Inc., 410 U .S .___, 114 S. Ct. 367

(1 9 9 3 ).......................... ........................................ .. . 20

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) . . . . . . . 1

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) . . . ........ 11

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986) . . 20

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968) 19

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) ............................. .. 12, 14

Polsby v. Chase, 970 F.2d 1360 (4th Cir. 1992), vacated

sub nom. Polsby v. Shalala, 507 U.S. 1048 (1993^ 17

Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., Case No. JFM 93-20 (D. Md.

April 15, 1994) ...................................... 17

St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502 (1993) 17

ii

Pages:

Veprinsky v. Fluor Daniel, Inc., 87 F.3d 881 (7th Cir.

1996)................... 9

Vinson v. Taylor, 23 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. 37 (D.D.C.

1980) ......................................... 20

Statutes: Pages:

29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(3) .......................................................... 10

29 U.S.C. § 2615 .................................................... ..............5

29 U.S.C. § 2617(a)(1) .............. .......................................... 5

42 U.S.C. § 12203 ............................................... 5

42 U.S.C. §§ 12141-65 .............. ................................ . . . . 5

42 U.S.C. §§ 12181-89 ................................... ................ .. . 5

1996 Md. Laws 469 ........................................................... 12

Alaska Stat. § 09.65.160 (1 9 9 3 ).............................. 12

Alaska Stat. § 09.65.160 (1 9 9 3 )................................. *

Cal. Gov’t Code § 1031.1 (West 1993) . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Civil Rights Act of 1964, section 7 0 1 (f)........... 2

Civil Rights Act of 1964, section 703 ......passim

Civil Rights Act of 1964, section 704(a) . passim

iii

Pages:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, section 708 ........................ 14

Civil Rights Act of 1964, section 717 . ................. .. 5

Fla. Stat. § 768.095 (1 9 9 1 )........................................... .. 12

Me . Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 26, § 598 (West 1995) . . . . . 12

N.M. Stat. Ann. § 50-12-1 (Michie 1995) . . . . . . . . . 12

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 40, § 61 (West 1995) . . . . . . . . 12

Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-1-105 (1995) ........................... .. 12

Other Authorities: Pages:

110 Cong. Rec. 7213 ...................... .. ............... .....................8

110 Cong. Rec. 8203 .......................... ........... .. 8

iv

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Introduction

Although supporting the result arrived at by the

Fourth Circuit, respondent has abandoned, and to some

degree repudiated, the central reasoning of the court of

appeals below.

The Fourth Circuit insisted that the general

prohibition against discrimination contained in section 703

of Title VII does not apply to any discriminatory acts by an

employer occurring after the end of the employment

relationship.1 Relying on that premise, the court of appeals

argued that Congress intended the scope of sections 703 and

704(a) to be co-extensive. (Pet. App. A-14 to A-15).

Respondent, on the other hand, concedes — as it must in

light of Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984)

that section 703 indeed applies to former employees, and

thus insists, contrary to the court below, that Congress did

not intend section 704(a) to protect all the persons entitled

to file charges under section 703. Respondent’s Brief ("R.

Br.") 34-36).2

ipet. App. A-14 (the Title VII definition of "unlawful employment

practice" "comprises discrimination with respect to certain aspects of

employment, and does not redress discriminatory practices after the

employment relationship has terminated") (emphasis in original); id. at

A-15 ("Title VII does not redress discriminatory practices, however

reprehensible, which occur after the employment relationship has

ended").

2R. Br. 9 ("There are legitimate reasons for offering more protection

against discrimination than retaliation").

Although respondent contends that Congress intended section

704(a) to be narrower than the substantive prohibitions of section 703,

it is clear on the face of the statute that section 704(a) is broader in at

least two respects. First, although section 703, in conjunction with

section 706, provides a remedy only to persons who have filed timely and

meritorious charges, section 704(a) provides remedies to all persons

retaliated against for filing charges, regardless of whether those charges

2

The Fourth Circuit relied heavily on the definition of

"employee" contained in section 701(f) of Title VII. We

noted in our opening brief the inherent ambiguity in that

statutory definition, stemming from the two different

meanings of the word "employed" (P. Br. 17-19). In this

Court, respondent disdains any analysis of the definition

contained in section 701(f), asserting instead that "an

employer knows who ‘his employees’ are" (R. Br. 24).

Respondent does not of course suggest that section 701(f)

defines "employee" as "the people whom employers call their

employees." Rather, respondent grounds its argument, not

on the statutory definition, but on what it asserts is

vernacular usage among employers.3

I. The Statutory Language

At this point there appear to be two areas of

agreement between the parties. First, both parties concur

that the term "employee" is at times utilized to refer to

former as well as current employees; respondent calls this

the "generic sense" of the term. Compare R. Br. 17-19 with

P. Br. 8-13. Second, the parties agree that the correct

interpretation of the word "employee" in section 704(a) turns

at least in part on the manner in which that term is

employed in Title VII. Compare R. Br. 9 ("‘Employee’ must

be understood within the context of Title VII") with P. Br.

13 et seq.

ultimately failed either on the merits or on some procedural ground.

Second, although section 703 provides remedies only for persons who are

themselves victims of employment discrimination on the basis of race,

color, religion, gender or national origin, section 704(a) protects persons

who never themselves suffered such discrimination, but who were

penalized for having opposed discrimination against others.

3Contrary to respondent’s description of common usage, a company

might well refer to one of its retirees as a "long time Widget Company

employee."

3

Respondent insists that the term "employee" in

section 704(a) must refer only to current employees because

Title VII always uses "employee" in this narrower sense

alone. "Title VII consistently uses ‘employee’ to refer to

current employees" (R.Br. 9).4

In our opening brief we noted that in nine different

instances Title VII uses the word "employee" in a context

which clearly includes former employees (P. Br. 14). With

regard to the remedial provisions of sections 706(g)(1) and

717, respondent asserts that the term "employee" means

"‘employee’ at the time of the adverse employment action;

i.e. discharge" (R. Br. 22). But a person who was an

employee "at the time of the adverse employment action" is

not a "current" employee but a former employee, albeit a

particular kind of former employee.5 When section 717(b)

requires "that an employee . . . be notified of any

[administrative] action taken on any complaint," and section

717(c) authorizes the filing of a civil action by an "employee"

"[wjithin 90 days of receipt of notice of final [agency] action"

the statute is clearly referring, not to events that will occur

at "the time of the adverse employment action" but at a

point in time well after that adverse action has occurred —

and after the plaintiff in a discharge case will have ceased to

be a current employee.

Three provisions of Title VII refer to "employees" of

the EEOC (see P. Br. 14-15). Respondent does not deny

4See R. Br. 21 ("‘Employee’ is not used differently in other sections

of Title VII"), 24 ("identical words used in different parts of the same act

are intended to have the same meaning.")

5Respondent’s reformulation is also insufficient to make sense of

section 717; if "employee" meant only an individual employed at the time

of the adverse action, section 717 would not apply, for example, if agency

officials decided to terminate pensions for all African-American retirees,

or to refuse to provide job references for laid-off female workers.

4

that these provisions apply to former EEOC workers, but

simply asserts that

they have nothing whatever to do with the

prohibitions on employers not to discriminate against

individuals or to retaliate against "his employees."

(R. Br. 22). While the subject matter of these three

provisions is not the relationship between private employers

and their former employees, the use of "employee" in these

sections to encompass former EEOC workers manifestly is

relevant to, and refutes, respondent’s assertion that

"employee" is "consistently" used in Title VII to refer solely

to current employees.

In our opening brief we noted that in six instances

Title VII uses the term "employee" where Congress must

have meant to include, or have been referring exclusively to,

future employees (P. Br. 15-16). Respondent’s somewhat

cryptic response to these provisions reads as follows:

Such sophistic reasoning cannot be taken seriously.

If "employee" includes individuals to be hired for

future employment, then why does § 704(a)

specifically protect "applicants for employment?"

(R. Br. 23.) Respondent appears to contend that "employee"

never includes future employees (R. Br. 23). If that were

the case, however, the six sections discussed in our opening

brief would be nonsensical; the BFOQ clause, for example,

would apply only to job applicants who were already

employed elsewhere, but not to out-of-work applicants. The

answer to the question posed by respondent is readily

apparent: even though "employee" is used in Title VII to

refer to future employees, section 704(a) included a

reference to applicants to assure that its protections would

apply to retaliation against unsuccessful applicants, e.g., to an

5

employer which refused to hire someone because of his or

her participation in protected activities.6

Respondent suggests that if Congress had intended

section 704(a) to protect former employees, it would have

utilized the term "individual" rather than "employee" in that

provision. (R. Br. 15) But use of the term "individual"

would have expanded the scope of section 704(a) far beyond

former employees; redrafted in that way, the section would

have applied to the entire population of the United States.7

Although the section 703(a) prohibition regarding

discrimination by employers uses the term "individual," it

does so in a way that could encompass only current or

"Respondent appears to assume that the "applicant" clause of section

704(a) refers to and protects only individuals who were current applicants

at the time of the retaliation. But Title VII frequently uses the term

"applicant" to refer to an individual who was actively seeking employment

at some point in the past. See, e.g., sections 717(b) ("applicants" to

receive notice of final agency action), 717(c) ("applicants" can bring civil

action). If the term "applicant" in section 704(a) indeed protects from

retaliation individuals who were applicants prior to, but not at the time

of, the retaliatory act, exclusion of former employees would be

particularly strange, since an individual who had never worked for the

employer in question would enjoy greater protection than one who had.

7The anti-retaliation provision of the Americans With Disabilities Act

of 1990 is deliberately framed to cover any "individual," 42 U.S.C.

§ 12203, even absent any employment connection between the retaliator

and the victim, because most of the substantive rights created by the

ADA deal with non-employment matters. E.g., 42 U.S.C. §§ 12141-65

(access to public transportation), 42 U.S.C. §§ 12181-89 (access to public

accommodations).

The anti-retaliation provision of the Family and Medical Leave

Act refers to retaliation against any "individual," 29 U.S.C. § 2615, but

the civil cause of action created by the FMLA is limited to claims by

"eligible employees." 29 U.S.C. § 2617(a)(1).

6

former employees or applicants.8 Similarly, Congress could

not, as respondent suggests, have reached former employees

simply by deleting the possessive "his" before "employees"

(R. Br. 19); that change would have encompassed every

employee of every employer in the United States, but would

not — on respondent’s view — have applied to former

employees, like petitioner, who were out of work at the time

of the retaliatory act.

Of course, Congress could have addressed this issue

more specifically. The drafters could have more clearly

indicated a desire to include former employees within the

scope of section 704(a) by using the very words "former

employee" in the text of the statute, or they could have used

the phrase "current employee" rather than "employee" to

exclude former employees unequivocally. The mere fact that

either meaning might have been, but was not, set forth

expressly does not prove that the contrary meaning was

intended. Although Congress clearly intended that other

provisions of Title VII apply to current and/or future and/or

former employees, the framers of that legislation never used

the words "current," "former," or "future," but left the

8Section 703(a)(1), for example, makes it an unlawful employment

practice to "fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual or

otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual’s race . . ." (emphasis added). The only "individual" to

whom this section could apply would be a job applicant or current or

former employee.

Although the anti-retaliation provisions in section 704(a)

regarding employment agencies and joint apprenticeship committees refer

to "individuals," that is because "individuals" is the term used in section

703 to denote the persons protected from discrimination. These

substantive and anti-retaliation provisions do not use the term "employee"

because the persons against whom an employment agency or joint

apprenticeship committee might discriminate are not ordinarily their

employees.

7

appropriate meaning of "employee" to be divined from the

particular context in which that word was utilized.9

The fact that Congress expressly forbade employer

retaliation against "applicants" is not inconsistent with

construing "employee" to include former employees.

Although "employee" is used throughout Title VII to refer

to past or future as well as current employees, Congress

often included the term "applicant" in other sections when it

wished to make clear that job seekers were to be protected.

It is scarcely to be believed that Congress, by adding the

term "applicants" to section 704(a) to assure that job seekers

would be protected against retaliation, intended also covertly

to narrow dramatically the scope of section 704(a) by

excluding former employees. On the contrary, the express

inclusion of applicants would make no sense if Congress

intended to exclude former employees from the scope of

section 704(a), because the inclusion in the provision of

applicants would permit a former employee seeking work

elsewhere to obtain the protections of section 704(a) by the

simple step of also filing a job application with his former

employer, thus becoming an "applicant."

To be sure, as respondent notes, Congress has at

times made express reference to former employees in other

statutes (R. Br. 15-16). But respondent does not deny that

at times Congress has also used the term "employee" in

’Respondent attaches significance to the fact that Congress did not

amend section 704(a) in 1991 when it amended Title VII, despite the fact

that two other statutes enacted in the early 1990s referred expressly to

former employees (R. Br. 15). But at the time when Congress adopted

the 1991 amendments to Title VII, all the appellate decisions to have

reached the issue had held that section 704(a) did apply to former

employees. The first decision clearly to the contraiy, Polsby v. Chase, 970

F.2d 1360 (4th Cir. 1992), vacated sub nom. Polsby v. Shalala, 507 U.S.

1048 (1993), did not occur until July 1992, some eight months after the

adoption of the 1991 amendments.

8

other statutes to refer to former employees (R. Br. 16-19).

"Employee" is a relatively elastic term which this Court, and

Congress, have understandably used in a variety of ways.

The term "employee" appears in more than 5100 sections in

the United States Code.10 It would be quite impossible for

Congress to review all those statutes whenever it used the

term in new legislation; it would be astounding if Congress

could use such a general term in thousands of statutes

without considerable variation in context, intent and

meaning. The meaning of the term "employee" in a

particular provision must be gleaned, not from the divergent

ways in which the word is used in other laws, but from the

context and purpose of the specific statute in question.

We noted in our opening brief that the authoritative

interpretations of section 704(a) in the legislative history of

Title VII repeatedly refer to its protections as extended to

"persons" (P. Br. 34). Respondent argues, "This is broader

language than Congress chose in the final version of the

statute" (R. Br. 33). Respondent evidently misapprehends

what occurred during the enactment of Title VII. At the

time when the Clark-Case Memorandum described the

precursor of section 704(a) as protecting "persons," the

relevant language of that section was precisely the same as

"the final version of the statute" — "employee."11

l0A Lexis search of the USCODE file for "text(employee)1' identifies

5167 sections. The term is used in sections of all but three of the fifty

titles of the United States Code.

“The anti-retaliation provision of the bill summarized by the

Memorandum forbade retaliation by an employer ''against any of his

employees or applicants for employment." See 110 Cong. Rec. 7213

(Clark-Case Memorandum); id. at 8203 (reprinting § 705(a) of bill during

subsequent debate that occurred prior to voting upon any proposed

amendments to the bill).

9

Respondent does not argue that Congress wanted to

leave former employees without federal protection from

retaliation. But, respondent asserts, Congress chose to

protect such individuals only from retaliation by new

prospective employers, against whom they had never filed

charges or testified, while permitting retaliation by the

former employer against whom those charges or testimony

was directed. Respondent offers no explanation as to why

Congress would have chosen to place outside the

prohibitions of § 704(a) the employer most likely to want to

retaliate against the charging party, and the only employer

who would benefit if coercive retaliation forced a former

employee to withdraw a charge.

A recent Seventh Circuit decision regarding the scope

of section 704(a) provides an additional text-based reason to

construe the statute to apply to former employees. Veprinsky

v. Fluor Daniel, Inc., 87 F.3d 881 (7th Cir. 1996). As that

opinion noted, section 704(a) prohibits retaliation inflicted

because the victim "‘opposed any practice made an unlawful

employment practice by this subchapter’" or "‘participated in

any manner in an investigation, proceeding or hearing under

this subchapter.’" Id. at 890 (emphasis added in part). In

many of the most common types of employment discrimination,

however, the individual affected would not be a current

employee of the employer in question at the time he or she

filed a charge or took part in a subsequent investigation or

proceeding. If section 704(a) protected only current

employees, that section — far from applying to "any"

violation or "any" proceeding — would not apply to almost

all charges of hiring discrimination, discriminatory dismissals,

or discrimination in pensions or other post-employment

benefits.

10

II. The Availability of State Remedies

Respondent advances two contradictory arguments

regarding state laws12 bearing on relations between

employers and former employees. At pp. 25-30 of its brief,

respondent contends that it is of no consequence whether

section 704(a) applies to former employees because

comparable protections for former employees are already

provided by state law; on this view, application of section

704(a) would be unnecessary and duplicative. At pp. 37-39

of its brief, on the other hand, respondent argues that

section 704 should not be applied to former employees

because state law remedies for those workers are far

narrower than section 704, and that applying section 704

would thus in some sense interfere with state law.13

Obviously both of these arguments cannot be correct; we

submit that neither is.

State defamation law, on which respondent

principally relies (R. Br. 29), is in many respects inadequate

to advance the prophylactic purposes of section 704.

Defamation law would not forbid a variety of extremely

effective retaliatory practices, such as (a) refusing to provide

any references at all for charging parties, (b) refusing to

include in references about charging parties any positive

12The National Labor Relations Act does not, as respondent suggests,

contain a general prohibition against blacklisting. Rather, that law

forbids an employer only from refusing to hire an individual "to . . .

discourage membership in any labor organization." 29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(3).

"Respondent may be asserting that, in those instances (e.g.,

retaliation against a current employee) in which section 704(a)

concededly does apply, its protections are excessive and "absurd," because

state laws — although permitting forms of retaliation forbidden by

section 704(a) — already provide "adequate" protection. Such a

contention would be simply a disagreement with the decision of Congress

to enact section 704(a) in the first place.

11

information, (c) placing in references regarding charging

parties types of adverse or personal information that would

not be included in references for any other former

employees,14 (d) including in a reference a truthful (albeit

retaliation-based) statement that the former employer would

not rehire, or recommend, the former employee. State

defamation law cannot be fairly read to endorse, or protect,

such abuses; these are simply problems that defamation law

does not undertake to address. In any event, Title VII

clearly does forbid an employer, regardless of state law, from

taking such adverse actions on the basis of race or gender

when providing recommendations regarding former or

current employees, or from taking such actions, for

retaliatory reasons, regarding recommendations concerning

current employees. There is no reason to treat any

differently retaliation-based adverse actions directed at

former employees.

Any state law remedies that might apply to some

types of retaliation would necessarily vary from one

jurisdiction to another. Respondent argues, for example,

that the caselaw-based "qualified privilege" for references

could immunize an employer from being sued for a

retaliatory adverse reference (R. Br. 38), while one amicus

supporting respondent insists, to the contrary, that a

retaliatory motive would eviscerate any such privilege.15

14Where an employer’s normal practice is to provide only laudatory

information, or no information at all, about former employees, Title VII

forbids an employer to single out former employees on the basis of race,

or in retaliation for having filed a Title VII charge, and as to them alone

dispense harmful — albeit accurate — information. See McDonald v,

Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976) (Title VII forbids

employer to impose greater sanction on transgressing employee on

account of his race).

15Brief Amiens Curiae of Washington Legal Foundation, at 15 n.7.

12

The scope of any such privilege might well turn on

differences in state laws. Respondent also notes that eleven

states have adopted special statues limiting defamation

actions based on employer references; the terms of these

statutes differ considerably,16 and numerous other states do

not have such laws.17 It is difficult, moreover, to see how

the existence of these state laws — the earliest of which was

enacted in 1986 - could control the interpretation of a

federal civil rights law adopted several decades earlier.

While there might well be some instances in which

retaliation forbidden by section 704 would also violate state

law, this crazy-quilt of state statutes and caselaw is entirely

inadequate to protect the viability of the Title VII charge

process. At best the viability of that process would vary

from state to state, a result flatly inconsistent with the need

for a uniform national enforcement scheme. See Patterson

16The California statute, for example, is limited to references provided

with regard to applicants for law enforcement positions. Cal. Gov’t

Code § 1031.1 (West 1993). The Oklahoma law applies only to

references provided with the employee’s consent. OKLA. Stat. Ann. tit.

40, § 61 (West 1995). Several of these provisions are expressly

inapplicable if the reference violated civil rights laws. Alaska Stat. §

09.65.160 (1993); Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-1-105 (1995). Most but not all

statutes deny immunity where the employer acted in bad faith or with a

malicious purpose. Alaska Stat. § 09.65.160 (1993); Fla. Stat. §

768.095 (1991); ME. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 26, § 598 (West 1995); N.M.

Stat. Ann. § 50-12-1 (Michie 1995); Tenn. Code Ann. § 50-1-105

(1995). Maryland recently enacted a law immunizing employers unless

they act with actual malice or intentionally or recklessly disclose false

information. 1996 Md. Laws 469 (May 14, 1996; effective October 1,

1996).

17Maryland law regarding interference with contracts would have no

application in a case such as this, since it applies only where a

contractual relationship has been created between the former employee

and the new employer. Bagwell v. Peninsula Regional Medical Center, 665

A.2d 297, 313 (Md. App. 1995).

13

V. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164, 183 (1989).

Frequently a former employee — even with the aid of skilled

counsel — could not reliably glean from state law whether

it would be safe to file an EEOC charge or to talk to an

EEOC investigator. Ordinary charging parties, who are

untutored in the law, and who do not enjoy the luxury of a

personal attorney on retainer to give advice about issues

such as state defamation law, could not know with any

assurance whether it was prudent to file a complaint with, or

give information to, the EEOC.

Even where substantive state law did forbid a

particular retaliatory act, that would ordinarily be insufficient

as a practical matter to safeguard the Title VII process. The

value of section 704(a) to a current or former employee lies

not only in its substantive scope, but also in the availability

of the informal and inexpensive Title VII enforcement

machinery to implement section 704(a) itself. A charging

party who is the victim of retaliation forbidden by section

704(a) can seek legal protection merely by submitting a

single-page handwritten charge to the nearest EEOC office;

the EEOC is then responsible for investigating and seeking

to resolve the problem, and the Commission can bring a civil

action in its own name to end the abuse. In contrast, a

charging party forced to rely on state law must retain a

private attorney to bring a state civil action — a course of

action far beyond the means of most charging parties,

especially those who are out of work.18 Any state law

remedies would of course be unavailable to the EEOC itself;

if former employees, in response to actual or threatened

retaliation, refused to file charges, or to cooperate in EEOC

18The remedies available in a state defamation action would often be

inferior to the remedies provided by Title VIL Neither injunctions nor

awards of counsel fees, two key elements of the relief authorized by

section 706, are ordinarily available in a defamation action.

14

investigations, the Commission could not file suit to stop

that retaliation, but would be relegated to pleading with the

justifiably frightened former workers to hire private counsel

and bring their own lawsuits against the employers at issue.

Respondent correctly observes that section 704(a), if

it applied to retaliatory references intended to punish former

employees, would forbid many practices that are not

prohibited by state defamation law. Such differences,

respondent asserts, would "conflict" with state law and lead

to "absurd" results. Worse yet, applying section 704(a) to

retaliatory references, respondent urges, would disturb the

"balance" which the states have seen fit to draw between

enforcing Title VII and protecting employees "against

groundless claims of retaliation" (R. Br. 40). Respondent

warns that "[djisgruntled former employees could sue former

employers over employment references even if . . . the

employer has complied with state law" (R. Br. 10). But the

proper "balance between employee and employer rights [is]

struck by Title VII" itself. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. at 182 n.4. Section 704(a) clearly does permit a

former employee to bring such suits — regardless of state

law — if retaliatory references were issued before he or she

was fired, or if an adverse reference was motivated by race

or gender. As to actions brought by these former

employees, Congress has clearly chosen to strike the balance

in favor of safeguarding the Title VII administrative process.

Respondent offers no reason why Congress, having done so

with regard to workers retaliated against while still

employed, would have left to the states the role of

determining the degree of protection, if any, to be accorded

to workers retaliated against after they were dismissed.

The ultimate answer to respondent’s argument based

on state law is found in Title VII itself. Section 708

provides that any state law that "purports to require or

permit the doing of any act which would be an unlawful

15

employment practice under this title" is superceded. Thus,

even if state law would permit an employer to issue a

retaliatory letter of reference, Congress has already provided

that such a law will not shield the employer from liability

under Title VII.

III. The Workability of Applying Section 704

to Former Employees

Respondent suggests that it would be impracticable

"to fashion equitable relief for a former employee" (R. Br.

31-32) But Title VII unquestionably does require courts to

fashion remedies for former employees in a variety of

circumstances. If, for example, an employer wrote a

retaliatory adverse reference letter just before discharging an

employee, that action would unquestionably be unlawful;

respondent does not deny that courts could and would

provide equitable and monetary relief in such a case, even

though, by the time the court acted, the victim of the

retaliation would have become a former employee. Thus

here the remedy for the allegedly retaliatory reference letter

of March 2, 1992 would be essentially the same as the

remedy that would have been provided had the same letter

been written on October 12, 1991, the day before petitioner

was dismissed. Similarly, if respondent had sent an adverse

post-dismissal reference letter because of petitioner’s race,

that would of course have been illegal, and petitioner would

have been entitled to equitable and legal relief. Where a

plaintiff has been injured by a retaliatory or race-based

reference letter, the fashioning of relief is not made harder,

or affected at all, by whether the victim was a current or

former employee at the time the letter was written, or by

whether the unlawful motive was retaliation or

discrimination on the basis of race.

16

The remedial problems hypothesized by respondent

are insubstantial.19 Title VII does not contain a general

prohibition against providing adverse information — truthful

or otherwise — to a prospective employer. What Title VII

does require is that an employer not make on certain

prohibited bases — e.g., race, gender, or the filing of a

charge with EEOC — its decision whether to make adverse

statements in a reference letter. Where an employer has

acted with an impermissible motive, a court can and should

forbid future violations of the law, and direct such corrective

measures as are necessary to place the victim in the position

which he or she would have occupied but for that violation

of federal law. Franks v. Bowman Trans. Co., 424 U.S. 747,

762-70 (1976). Congress entrusted the framing of particular

injunctive decrees to the sound discretion of district judges.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 416-20

(1975).20

Respondent expresses concern that, if former

employees were protected from retaliation, baseless

retaliation claims might be filed regarding reference letters

written decades after a worker had left the employ of a

19Respondent also expresses concern about what types of retaliatory

actions by an employer against a former employee would be actionable

(R. Br. 29 n.37, 32). But this affords no reason to deny protection to

former employees; the kinds of retaliatory actions forbidden against

former employees are the same kinds of actions which section 704(a)

forbids against current employees.

“ Standard provisions in settlements of Title VII discriminatory

discharge cases deal with letters of references or responses to other

inquiries from prospective employees. A neutral text is often agreed

upon, discharges are changed to resignations, all telephonic inquiries are

routed to a designated person, etc.

17

particular firm (R. Br. 32-33).21 Actual experience,

however, demonstrates that this does not occur, in the

reported cases, as in the instant case, disputes regarding

allegedly retaliatory reference letters typically arise within a

matter of months after the plaintiff ceased working for the

employer in question.22 In any event, any problems posed

by post-employment retaliation claims are not different in

principle from other post-employment claims. Title VII

indisputably provides protections against other practices that

could occur long after a plaintiff has stopped working for an

employer. Title VII would clearly be violated if, for example,

an employer decided in 1996 to slash pension benefits for

Roman Catholics who had retired in 1966. If respondent

21Respondent insists that the district judge’s rejection of the merits

of petitioner’s dismissal claim demonstrates that petitioner’s retaliation

claim is baseless. Specifically, respondent argues that the trial judge who

heard that dismissal claim necessarily found that all the adverse

information in respondent’s March 2,1992, reference letter was "true" (R.

Br. 6, 30, 39). There is, however, no decision by the district court

regarding the contents of the letter. Indeed, there were neither an

opinion nor any findings of fact following the trial of petitioner’s

discharge claim. Rather, the district judge after a bench trial merely

entered a one sentence order stating that "judgment is entered in favor

of Defendant, Shell Oil Company." Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., Case No.

JFM 93-20 (D. Md. April 15, 1994) (Judgment).

The mere fact that respondent prevailed at the trial of the

discharge claim does not mean that the trier of fact accepted all, or even

any, of respondent’s proffered explanations for dismissing petitioner. If

the trier of fact had concluded that the reasons proffered by the

employer were fabrications — and that the adverse reference letter was

a tissue of lies — the court was certainly authorized on that basis to find

that petitioner’s dismissal was racially motivated, but it was not required

to do so. St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502, 511 (1993).

nE.g., Bailey v. USX Corp., 850 F. 2d 1506 (11th Cir. 1988)

(employment ended August 29, 1984; adverse reference provided in

April, 1985); Polsby v. Chase, supra note 9 (employment terminated July

9, 1985; adverse reference written on December 24, 1985).

18

were to adopt a policy of refusing to provide references for

female former employees, a woman who had not worked for

Shell since 1970 — but could not obtain a needed job

reference in 1996 — clearly would be entitled to relief.

As a practical matter, however, any disputes about

references from an employer of ten or twenty years earlier

are exceedingly unlikely. Prospective employers are

ordinarily interested in an applicant’s record in positions

held within the previous few years; former employers often

will no longer have records regarding employees who left

decades earlier. In the rare case in which a prospective

employer sought, received and relied on adverse information

regarding a job held by an applicant many years in the past,

the applicant would be hard pressed to convince a trier of

fact that the former employer still held a grudge after all the

intervening years.

In our opening brief we suggested that the Fourth

Circuit’s interpretation of section 704(a) would permit

employers to sabotage resort to the Title VII administrative

process by victims of discrimination (P. Br. 23-30).

Respondent maintains, however, that the critical purpose of

the Title VII enforcement scheme is to "quickly resolve

employment disputes" (R. Br. 32). Noting that section

706(e)(1) establishes a limitations period of 180-300 days,

respondent reasons that the policy of avoiding protracted

disputes would be advanced, a fortiori, if aggrieved

individuals -— in this case former employees subjected to

retaliation —- were precluded completely from seeking

redress under Title VII for their injuries. In a somewhat

Orwellian turn of phrase, respondent describes this proposed

scheme — under which the number of days within which

certain retaliation charges would have be filed is set at

19

zero23 — as a "‘statute of repose’" (R. Br. 33).

The central purpose of Title VII, however, was not to

eliminate or shorten disputes between employers and

employees, but to eradicate discrimination. There were

many decades, to be sure, when the national and state

governments resolutely protected employers from

discrimination litigation by openly tolerating, if not

encouraging, racist employment practices. At least since.

1964, however, the federal government has chosen a

different course, making the elimination of invidious

discrimination "a policy that Congress considered of the

highest priority." Newman v. Piegie Park Enterprises, 390

U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

Conclusion

Respondent suggests that limiting the protections of

section 704(a) to current employees (and current applicants)

would create only a minor and relatively unimportant

limitation on the scope of that provision. In reality, such a

limitation would go a long way toward eviscerating section

704(a), and with it the protections essential to the viability

of the Title VII enforcement scheme.

Under the interpretation of section 704(a) advanced

by respondent, that provision would not protect from

employer retaliation victims of discriminatory dismissals

(since they would be former employees by the time they filed

Title VII charges), former applicants for employment who

filed charges of discrimination in hiring (unless they had

reapplied at the time of the retaliatory act), or victims of

discrimination against former employees (e.g. pension

discrimination). Former employee witnesses being

questioned by EEOC — witnesses who might ordinarily be

“ In the instant case petitioner filed his Title VII charge eight days

after the allegedly retaliatory letter.

20

more willing than current employees to provide candid

information — could be openly threatened by employers

under investigation by EEOC.

These categories of persons to be excluded from the

protections of section 704 represent a substantial portion of

all Title VII complainants. Many of the Title VII cases that

have been considered by this Court involved claims of

discrimination in dismissals, hiring or pensions. We set forth

in the Appendix to this brief a list of 22 such decisions of

this Court. In many sexual harassment cases plaintiffs only

file charges with EEOC after they have stopped working for

the employer at issue; Teresa Harris24 and Mechelle

Vinson25 had both become former employees — and on

respondent’s view were thus subject to whatever forms of

retaliation their former employers could devise — by the

time they filed their Title VII charges.

For the above reasons, the decision of the Fourth

Circuit should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

A l l e n M. L e n c h e k

(Counsel of Record)

401 E. Jefferson Street, Suite 208

Rockville, MD 20850-2616

(301) 217-5838

^Harris v. Forklift Sys., Inc., 410 U.S. ___, 114 S. Ct. 367 (1993).

Harris resigned on October 1, 1987, as a result of the harassment, id. at

369, and filed her Title VII charge on October 10, see Joint Appendix at

10-11, id.

25Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986). Vinson took

indefinite sick leave in September, 1978, id. at 60, and in November of

that year finally resigned and filed a charge with EEOC, see Vinson v.

Taylor, 23 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. 37 (D.D.C. 1980).

Eric Schnapper

UNivERsrry of Washington

School of Law

1100 NE Campus Parkway

Seattle, WA 98105-6617

(206) 616-3167

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Petitioner

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

St. Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, 509 U.S. 502

(1993)(discharge claim).

EEOC v. Arabian American Oil Co., 499 U.S. 244

(1991)(discharge claim); see 857 F. 2d 1014(5th Cir.

1988)(charge filed "after" dismissal).

Yellow Freight System, Inc. v. Donnelly, 494 U.S. 820

(1990)(hiring claim).

EEOC v. Commercial Office Products Co., 486 U.S. 107

(1988)(discharge claim).

Corporation of the Presiding Bishop v. Amos, 483 U.S.

327 (1987)(discharge claim).

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564

(1985)(hiring claim).

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345

(1983)(discharge claim).

Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219 (1982)(hiring

claim).

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461

(1982)(discharge and failure to rehire claim).

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248 (1981)(discharge claim).

New York City Transit Auth. v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568

(1979)(hiring claims and discharge claims).

Fumco Construction Co. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978)(hiring claim).

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977)(hiring claim).

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63

(1977)(discharge claim).

2a

International Union of Electrical Workers v. Robbins &

Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229 (1976)(discharge claim).

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976)(discrimination in

retiree benefits).

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273

(1976)(discharge claim)

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454

(1975)(discharge claim)(pending charge amended to add

discharge claim following petitioner’s dismissal).

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974)(discharge claim)(petitioner fired September 29,

1969; charge filed October 27, 1969).

Espinoza v. Farah Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86 (1973)(hiring

claim).

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792(1973)(hiring claim).

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542

(1971)(hiring claim).