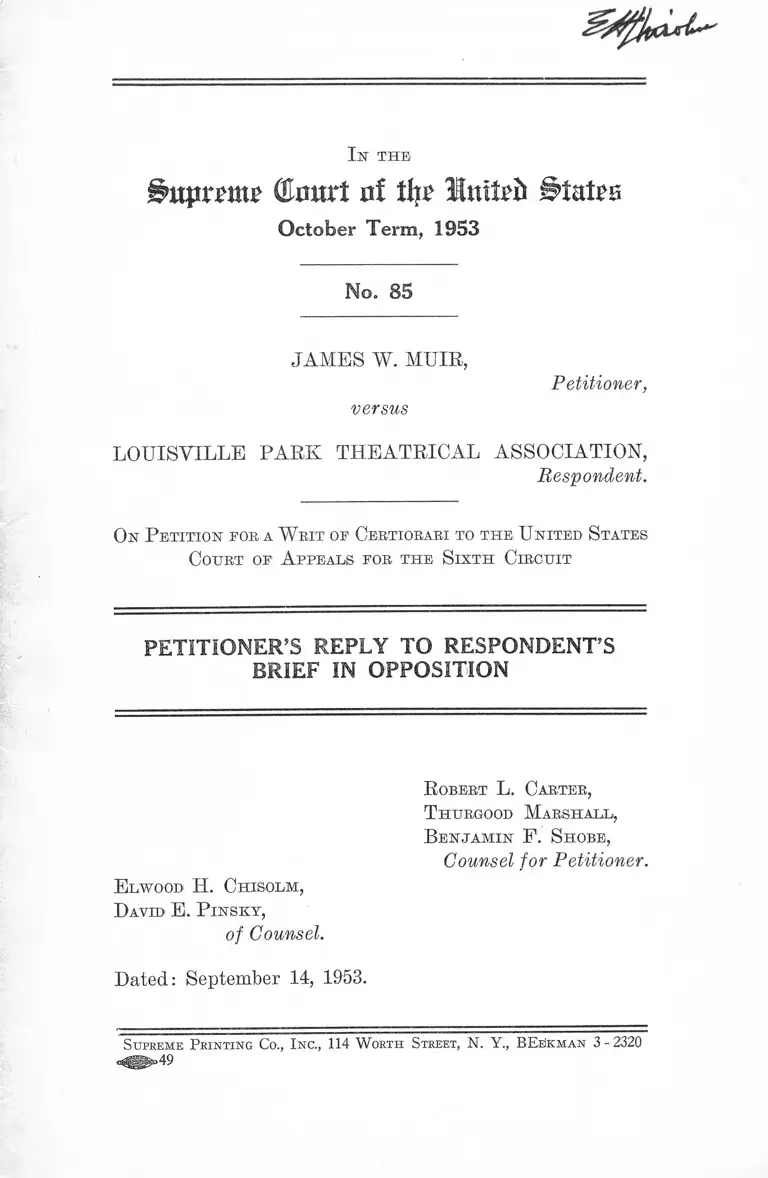

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association Petitioner's Reply to Respondent's Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

September 14, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association Petitioner's Reply to Respondent's Brief in Opposition, 1953. aed713eb-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/920d3007-4c74-4326-86d3-a2ed4c4aa41c/muir-v-louisville-park-theatrical-association-petitioners-reply-to-respondents-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

$ t t p r a t t ? (Hmtrt o f tl?? I t t i f c f t S t a t e s

October Term, 1953

No. 85

JAMES W. MUIR,

Petitioner,

versus

LOUISVILLE PARK THEATRICAL ASSOCIATION,

Respondent.

On P etition for a W rit of Certiorari to th e U nited S tates

Court of A ppeals for th e S ix t h C ircu it

PETITIONER’S REPLY TO RESPONDENTS

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Be n ja m in F. S hobe,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. C h iso lm ,

D avid E . P in s k y ,

of Counsel.

Dated: September 14, 1953.

S upreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y., BE eSk m a n 3 - 2320

)

INDEX

I. Jurisdiction ............................................................... 1

II. The Questions Presented Are Not M o o t .............. 1

III. Petitioner Was Refused Admission Pursuant to

Rules and Regulations of the City of Louisville.. 4

Conclusion .................................................................. 7

Table of Cases Cited

Alejandrino v. Quezon, 271 U. 8. 528, 535 ...................... 3

Atherton Mills v. Johnston, 259 U. S. 1 3 ...................... 3

Belcher Land Mortgage Co. v. Hazard Coal Corp., 15

F. 2d 481 (C. A. 6th, 1926) ........................................... 5

Board of Park Commissioners v. Speed, 215 Ky. 319,

285 S. W. 212 (1926) .................................................... 4

Chesapeake & 0. R. Co. v. City of Morehead, 223 Ky.

698, 4 S .W . 2d 726 (1928) ............................................... 5

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 1 7 ................................. 6

Culver v. City of Warren, 84 Ohio App. 373, 83 N. E.

2d 82 (1948) ........................................................... 5

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429 ............ 3

Douglas v. Jeanette, 319 H. S. 157, 165 .......................... 2

Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 335 U. S. 303, 312-13.. 4

Gray v. University of Tennessee, 342 U. S. 5 1 7 ............ 3

Great Northern Railway Co. v. Delmar Co., 283 U. S.

686, 691 ............................................................................. 5

Harris v. City of St. Louis, 233 Mo. App. 911, 111 S. W.

2d 995 (1938) ........................................................... 5

Kern v. City Commissioners, 151 Kans. 565, 100 P.

2d 709 (1940)

PAGE

5

11

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. I). W. Va.

1948) ................................................................................. 5

Leslie County v. Maggard, 212 Ky. 354, 279 S. W. 335

(1926) ............................................................................... 5

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 .... 3

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545, 549

(E. D. Va. 1949) ............................................................. 6

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ................................... 6

Park Commissioners of Ashland v. Shanklin, 304 Ky.

43, 199 S. W. 2d 721 (1947) ....................................... 4

Public Utilities Commission v. United Fuel Gas Co.,

317 U. S. 456, 466 ........................................................... 3

Public Utilities Commission of the District of Columbia

v. Poliak, 343 U. S. 451, 461-62 .................................. 6

Southern P. Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce Com

mission, 219 U. S. 498, 514-15 ....................................... 4

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ....................................... 3

Trailmobile Co. v. Whirls, 331 U. S. 40, 48-49 .............. 3

United States v. Hamburg-Amerikanische Co., 239 U. S.

466 ..................................................................................... 3

United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Assoc., 166

U. S. 290 ........................................................................ 3

Other Citations

17 C. J. S., Contracts, Sec. 3 1 8 ......................................... 5

Louisville Courier Journal

July 5, 1953 ................................................................. 2n

July 12, 1953 ............................................................... 2n

July 19, 1953 ............................................................... 2n

July 26, 1953 ............................................................... 2n

August 2, 1953 ............................................................. 2n

August 9, 1953 ............................................................. 2n

August 16, 1953 ........................................................... 2n

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

Louisville Defender

July 23, 1953 ............................................................... 2n

Louisville Times

August 11, 1953 ........................................................... 2n

New York Times

June 18, 1953 ............................................................... 6

Title 28, U. S. Code, Sec. 1254(1) .................................. 1

1st t h e

£>uprmp (tart nf % Staten

October Term, 1953

No. 85

----------- o-----------

J am es W . M u ir ,

Petitioner,

versus

L ouisville P ark T heatrical A ssociation,

Respondent.

On P etition for a W rit oe Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates

C ourt of A ppeals for th e S ix t h C ircu it

----------------------------- o----------------------------

PETITIONER’S REPLY TO RESPONDENT’S

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

I.

Jurisdiction.

The statement in the petition for the writ of certiorari

that petitioner invokes the jurisdiction of this Court on the

basis of Title 28, United States Code, Section 1251(1) is, of

course, a typographical error. Jurisdiction is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1254(1).

II.

The Questions Presented Are Not Moot.

Respondent raises the identical issue of mootness that

it asserted in the Court of Appeals. By disposing of this

2

case on the merits, the Court of Appeals clearly indicated

that this contention had no substance. It has no greater

merit in this Court.

The petition for the writ of certiorari brought to the

attention of the Court the fact that subsequent to the

expiration of the 1947-1951 agreement, a new agreement

was entered into between respondent and the City for the

1952 summer season. This agreement appears as Appen

dix A to the petition. While the petition did not state that

theatrical performances were presented by respondent dur

ing the 1952 season, this is the fact. Significantly, respond

ent does not deny the existence of the 1952 agreement nor

the fact that performances were given pursuant to it. The

renewal of the 1952 agreement for the 1953 season was also

set forth in the petition. Petitioner can now further advise

the Court that musicals were again presented at Iroquois

Amphitheatre during the months of July and August, 1953,

for a six week season under the respondent’s sponsorship.1

Negroes were again denied admittance.2 Respondent’s

Brief in Opposition likewise fails to deny any of the facts

relating to 1953.

Respondent’s argument thus narrows down to a highly

technical contention that this Court is bound by the record

and cannot consider events which have transpired subse

quently. But this argument necessarily falls by the weight

of its own fundamental inconsistency. Respondent’s argu

ment necessarily rests on the proposition that a court of

equity looks to the future, Douglas v. Jeanette, 319 U. 8.

157, 165, and will normally decide an appeal on the basis

1 The Louisville Courier Journal, July 5, 1953, § 5, p. 2, col. 1;

id., July 12, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 4; id., July 19, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 4;

id., July 26, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 4; id., Aug. 2, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 2;

id., Aug. 9, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 4; id., Aug. 16, 1953, § 5, p. 1, col. 6.

The Louisville Times, Aug. 11, 1953, p. 12, col. 1.

2 The Louisville .Defender, July 23, 1953, p. 1, col. 8.

3

of circumstances existing at the time of the appeal. Public

Utilities Commission v. United Fuel Gas Co., 317 U. S. 456,

466; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. 8. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. However, in so doing, the

Court must necessarily consider circumstances which have

transpired subsequent to the entry of judgment in the trial

court. This is a well established proposition. In deciding

whether a question is moot, this Court will consider facts

beyond the record. Gray v. University of Tennessee, 342

U. S. 517; Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 IJ. S. 429;

Trailmobile Co. v. Whirls, 331 U. S. 40, 48-49; Atherton

Mills v. Johnston, 259 U. S. 13; United States v. Hamburg-

Amerikanische Co., 239 U. 8. 466; Alejandrino v. Quezon,

271 IT. 8. 528, 535.

Similarly, in deciding cases on the merits, this Court

has looked beyond the record to consider the effect of

circumstances occurring after judgment in the trial court.

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 IT. S. 637; United States v. Trans-

Missouri Freight Assoc., 166 U. 8. 290, 308-9. In Sweatt v.

Painter, supra, a new Negro law school had been put into

operation after judgment had been entered in the trial court.

In holding that Texas did not provide a law school educa

tion for Negroes equal to that provided for white students,

this Court gave full consideration to the facts relating to

the better facilities in the new law school. Similarly, in

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, some of the more

onerous restrictions which had been placed on McLaurin

were removed between the time the decree was entered in

the district court and the time the case was argued in this

Court. This Court again looked beyond the record and

considered the facts as they existed at the time of argument.

Petitioner merely asks the Court to follow the same pro

cedure applied in Sweatt, McLaurin and numerous other

4

cases. Any other course would result in the grossest injus

tice imaginable. By utilizing successive lease agreements

covering only a single summer, respondent could success

fully frustrate petitioner’s right of appeal, for the agree

ment in force at the time of the trial would have expired

by the time of appeal. Cf. Southern P. Terminal Co. v.

Interstate Commerce Comm., 219 U. S. 498, 514-15; Ford

Motor Co. v. United States, 335 U. S. 303, 312-13. This

Court could hardly sanction such a result.

III.

Petitioner Was Refused Admission Pursuant to Rules

and Regulations of the City of Louisville.

1. Respondent misconceives the reason for reliance on

Park Commissioners of Ashland v. Shanklin, 304 Ky. 43,

199 S. W. 2d 721 (1947), and Board of Park Commissioners

v. Speed, 215 Ky. 319, 285 S. W. 212 (1926). Petitioner does

not ask the Court to grant the writ of certiorari in order to

decide a question of Kentucky law. But we submit that the

Kentucky decisions are indirectly relevant. The Shanklin

and Speed cases state that a city department of parks

cannot lawfully lease public park property to an inde

pendent proprietor and thereby relinquish control over its

use. Hence, if the facts relating to the relationship between

the City and respondent are at all equivocal—if there is

some doubt as to the extent of control exercised by the

City over the operations of respondent—this Court is justi

fied in drawing the inference that the parties contracted

with full knowledge of state law and thus intended that the

City of Louisville retain the right to control the operations

of respondent. This is merely an application of the well-

established rule that where a contract is susceptible of two

meanings, one legal and the other unlawful or contrary to

5

public policy, the former will be adopted so as to uphold

the contract. Great Northern Railway Co. v. Delmar, 283

U. S. 686, 691; Belcher Land Mortgage Co. v. Hazard Coal

Corp., 15 F. 2d 481 (C. A. 6th 1926); Chesapeake d 0. R. Co.

v. City of Morehead, 223 Ky. 698, 4 S. W. 2d 726 (1928) ;

Leslie County v. Maggard, 212 Ky. 354, 279 S. W. 335 (1926);

17 0. J. S., Contracts, Sec. 318.

2. Petitioner reasserts that the decisions in Lawrence

v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Va. 1948); Culver

v. City of Warren, 84 Ohio App. 373, 83 N. E. 2d 82 (1948);

and Kern v. City Commissioners, 151 Kans. 565, 100 P. 2d

709 (1940), are in sharp conflict with the instant case, not

withstanding respondent’s attempt to harmonize them. In

all cases Negro citizens were denied the use of a public

facility by the use of a leasing arrangement. Any factual

distinction between the cases rests on the differences between

a swimming pool and an outdoor amphitheatre. A swimming

pool is useful only in the summer. On the other hand, an

outdoor amphitheatre has some usefulness in the other

seasons, although its period of principal utility is certainly

the summer months—the period covered by the leases be-

tween the City and respondent. Such a distinction between

the instant case and Lawrence, Culver and Kern is hardly

significant.

The instant case in fact presents a much stronger

picture of state action violative of the 14th Amendment

than that in any of the swimming pool cases. In the latter

cases, as well as in Harris v. City of St, Louis, 233 Mo. App.

911, 111 S. W. 2d 995 (1938), each of the lessees formulated

its own admission policy. No state policy—no state regula

tion no state action of any kind was the immediate cause

of the refusal to admit Negroes. In the instant case, how

ever, City regulations require racial segregation in the use

of the City’s parks and Iroquois Park is designated for the

exclusive use of white persons (P. 44). Significantly,

6

respondent, in answer to our fourth reason for the allow

ance of this writ, does not deny this. Thus, respondent’s

refusal to admit petitioner Muir and other Negroes was

required by state law; and in so acting-, respondent clearly

acted as an instrumentality of the state in carrying out

state policy. Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536; cf. Civil

Hights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17; Public Utilities Commission

of the District of Columbia v. Poliak, 343 U. S. 451; 461-62;

Nash y. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545, 549 (E. D.

Va. 1949).

A recent occurrence highlights this point. In June, 1953,

there was presented at Iroquois Amphitheatre for a three-

week run a musical drama based on the life of President

Lincoln. To these performances Negroes were admitted.

The New York Times reported on June 18,1953 that Mayor

Charles P. Farnsley of Louisville had temporarily lifted

“ [t]he historic ban against admitting Negroes to Louis

ville’s white city parks” (p. 38, col. 1). This serves to

dramatize the crucial fact that it is city policy and city action

which determines whether, if at all, Negroes are admitted to

Iroquois Amphitheatre. In the light of this, respondent’s

contention that there is no showing that petitioner has been

denied the use of the Amphitheatre becomes especially

transparent.

The conclusion thus becomes inescapable that when

respondent denied petitioner admittance to the Amphi

theatre, it acted for the state and under color of state law.

7

Conclusion,

W herefore, f o r the reasons h ereinabove stated, it is

resp ectfu lly subm itted that the petition fo r a w rit o f ce rti

ora r i should be granted .

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

B e n ja m in F. S hobe,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. Ch iso lm ,

D avid E . P in e r y ,

of Counsel.

Dated: September 14, 1953.