Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Motion for Leave to File and Petitioners' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Motion for Leave to File and Petitioners' Reply Brief, 1970. 075fca7e-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/92379f42-aae2-4294-8d86-e93abc6153b9/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

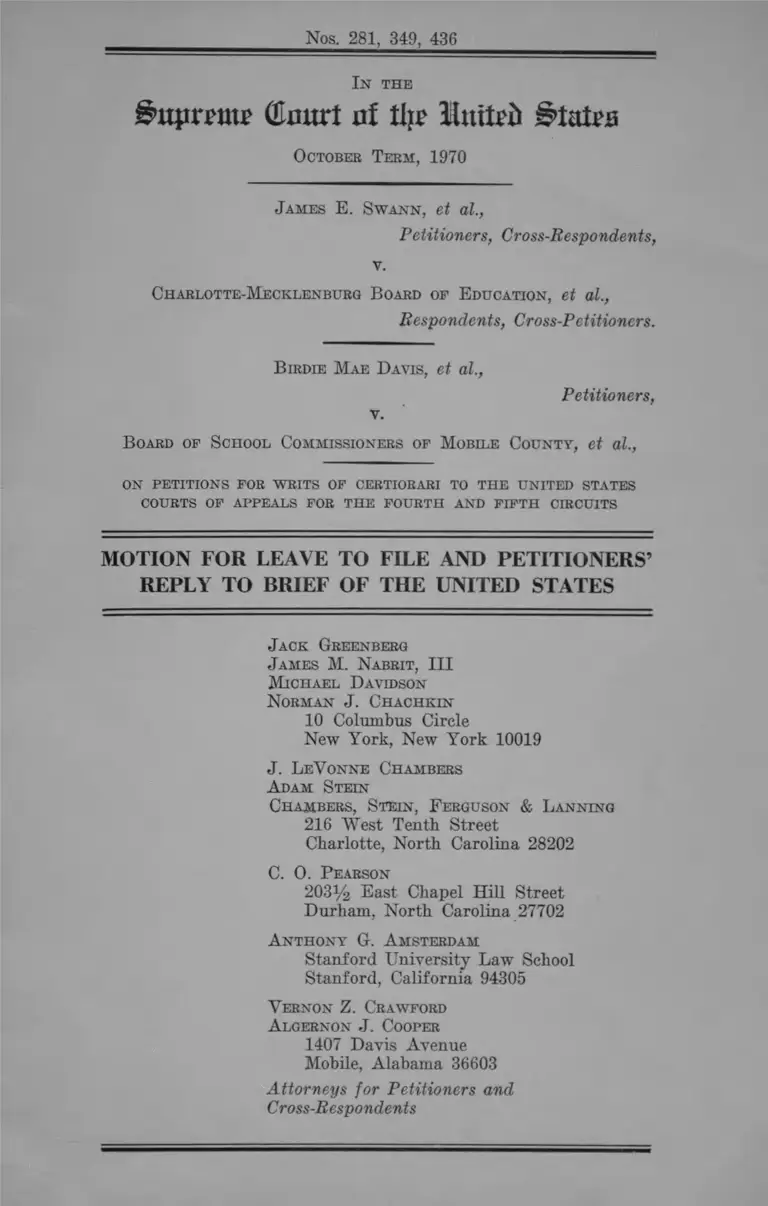

Nos. 281, 349, 436

In the

dmtrt at tlja Hutted States

October Teem, 1970

James E. Swann, et al.,

Petitioners, Cross-Respondents,

v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Boaed of Education, et al.,

Respondents, Cross-Petitioners.

Biedie Mae Davis, et al.,

Petitioners,

Boaed of School Commissionees of Mobile County, et al.,

ON PETITIONS FOR WEITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURTS OF APPEALS FOE THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CIRCUITS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND PETITIONERS’

REPLY TO BRIEF OF THE UNITED STATES

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Davidson

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. LeV onne Chambers

A dam Stein

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Lanning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. O. Pearson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

V eenon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners and

Cross-Respondents

In the

i>upnmtp (ta rt nf % llniUb States

October T erm , 1970

J ames E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners, Cross-Respondents,

v.

Charlotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Respondents, Cross-Petitioners.

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

B oard of S chool Commissioners of M obile County, et al.

ON PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURTS OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CIRCUITS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE REPLY BRIEF

Petitioners respectfully request leave to file the attached

reply to the brief of the United States. This reply is being

filed less than three days before the time the case will be

called for hearing. See Rule 41, Rules of the Supreme

Court.

The brief of the United States was filed on October 6

and received by petitioners’ counsel on October 7 and 8.

2

Accordingly, it was not possible to complete this reply and

have it printed for filing until October 10. Special arrange

ments are being made to serve counsel who will be arguing

the case, prior to the arguments.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. N abeit, III

M ichael D avidson

N orman J. Ch a ch k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam S tein

Chambers, S tein , F erguson & L anning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. 0. P earson

2031/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

A n th o n y G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners and

C ross-Resp ondents

I n THE

(£mu*t of % Mnxtib States

October T erm , 1970

James E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners, Cross-Respondents,

v .

Charlotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Respondents, Cross-Petitioners.

B irdie M ae D avis, et al.,

Petitioners,

v .

B oard of S chool Commissioners of M obile County, et al.

ON petitions for writs of certiorari to the united states

courts of appeals for the fourth and fifth circuits

PETITIONERS’ REPLY TO

BRIEF OF THE UNITED STATES

Several arguments advanced by the United States in its

brief amicus curiae occasioned this reply.

(1) At p. 17, the Government attributes to petitioners

the position that the Constitution requires “ the ratio of

white to black students in each school [to be] . . . as near

as possible to the ratio of white to black students in the

system as a whole.” This is not petitioners’ position.

Nothing in petitioners’ briefs suggests this position, which

2

the Government elsewhere characterizes as “ racial balance”

(pp. 16, 18-21, 23).

Petitioners’ plan for the desegregation of the Mobile

public school system in No. 436 does not depend upon a

theory of “ racial balance.” 1 Nor does Judge McMillan’s

plan for the desegregation of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

public school system in Nos. 281 and 349 depend upon a

theory of “ racial balance.” 2 “Racial balance” is a whipping-

boy that respondents and the Government find it convenient

to belabor. But it has nothing to do with petitioners’ con

tentions respecting the requirements of the Constitution.

(2) Petitioners’ contentions do not depend upon “ratios.”

They would permit 50-50 schools to exist, for example, in a

70-30 school district where residential stability and other

characteristics of the school population did not threaten

resegregation, and the history of the school board per

1 See Brief for Petitioners in No. 436, pp. 63-79.

2 See the Government’s quotation from Judge McMillan’s opinion

at p. 21. After the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board had con

sistently failed to produce an acceptable desegregation plan, Judge

McMillan was compelled to appoint an expert to devise a plan.

He was thereby obviously required to instruct the expert concern

ing the ideal objectives of the plan—something that would not

have been necessary if the board had developed anything approxi

mating a satisfactory plan of its own. In this context only, Judge

McMillan resorted to ideals defined by ratios—but with the clear

recognition that substantial deviations from the ratios would be

permitted where other practical and educational considerations

called for them. And the ultimate plan approved by Judge Mc

Millan does not in fact involve racial ratios in each school that

reflect those of the district as a whole.

Judge McMillan expressly noted that his decision does not rest

on a conclusion that “racial balances” are constitutionally required.

He said:

“ This court has not ruled, and does not rule, that ‘racial bal

ance’ is required under the Constitution; nor that all black

schools in all cities are unlawful; nor that all school boards

must bus children or violate the Constitution; nor that the

particular order entered in this case would he correct in other

circumstances not before the court” (emphasis in original)

(Brief Appendix, p. 12).

3

formance did not require more exacting demands to guard

against evasions. What petitioners do urge is simply that

this Court should announce principles for the ultimate

form of school desegregation plans which meet two re

quirements :

First, they fulfill the promise and the constitutional hold

ing of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),

that no black child is to be assigned to a racially identi

fiable “black” school such as the all-black and virtually all

black schools which the Fifth Circuit has permitted to exist

in Mobile and which the HEW plan would permit to exist

in Charlotte-Mecklenburg.

Second, they announce this first requirement in terms

that are sufficiently clear, unmistakable, and decisive so

that the Court’s opinion in these cases will not spawn 16

more years of litigation like the 16 years of litigation that

followed Brown.

(3) The Government’s position fails to meet either re

quirement. The Government urges that:

An appropriate standard should give proper attention

to a number of circumstances, such as the size of the

school district, the number of schools, the relative

distances between schools, the ease or hardships for

the school children involved, the educational sound

ness of the assignment plan, and the resources of the

school district. (P. 8)

If 16 years of litigation under Brown have demonstrated

anything, it is that the enunciation of this “ standard” by

this Court in this year 1970 would be an unmitigated

disaster. Under this standard, southern desegregation will

remain an unresolved issue, and litigation of how many

black children can he penned in all-black schools will still

be going on, in 1986.

4

(4) The only justification that the Government offers

for this unserviceable standard is the notion of deference

to “ the traditional neighborhood method of school assign

ment” (p. 9; see p. 24). But we are talking about desegre

gating schools that have never had a “traditional neigh

borhood method of school assignment.” Time out of mind

prior to Brown, both Mobile and Charlotte-Mecklenburg

had school assignment systems that took black children

out of their “neighborhoods” to black schools and white

children out of their “neighborhoods” to white schools.

After Brown, both used plans that were not “neighborhood”

plans.3 Recently, both developed “ neighborhood school”

schemes whose design and effect were to perpetuate segre

gation. If the neighborhood school system had any other

“benefits” (p. 9), they had escaped local notice altogether

during many years, and now continued to be subordinated

to the interests of segregation for schools were located,

their capacities designed, their grades structured, their

zone lines drawn, and their “neighborhoods” thus shaped

to achieve continued segregation of the races.

The Government admits that all of this is so as to Mobile

and Charlotte-Mecklenburg (pp. 12-16), but seem to suggest

that Mobile and Charlotte-Mecklenburg are aberrations.

They are not aberrations. I f one is to go outside these

records, one will find that no school district which practiced

the sort of racial discrimination condemned in Broivn had

a “ traditional neighborhood” school system. They all sent

blacks to black schools and whites to white schools without

regard to “neighborhoods” or geographic proximity. These

are the school systems that are at issue here.

But we do not think that the Court should go outside

the record. I f there are school districts which have truly

3 Indeed, in No. 436, the Mobile School Board adamantly re

sisted the principle of neighborhood schools. See petitioners’ brief

in No. 436, p. 29, n. 26.

5

had “ traditional neighborhood” school systems, they lie

beyond the scope of this Court’s post -Brown experience

and doubtless differ in so many ways from Mobile and

Charlotte-Mecklenburg that nothing the Court decides

herein could affect them. To reason from the supposed

nature and “benefits” of those systems without a record

adequately describing them would be perilous enough even

if such systems were in question. But the only systems

in question here are those that have traditionally subordi

nated or shaped neighborhoods to race; and, as to them,

the Government’s “ traditional neighborhood” school prin

ciple is manifestly hollow.

(5) The Government’s reasoning from the “neighbor

hood” school premise is as faulty as the premise. We

understand it to say that because various devices have been

used by southern school boards to make the “neighborhood”

school principle a serviceable tool of segregation—i.e.,

school location, school size manipulations, grade structure

manipulation, zone line manipulation (pp. 12-16)—these

same devices, but only these, may be used as “ the focal

point of a proper remedy . . . to disestablish the dual

system and eliminate its vestiges (p. 16; see p. 25). Two

things are -wrong with this argument as a basis for con

cluding that “ a system of pupil assignment on the basis

of contiguous geographic (residence) zones . . . is consti

tutionally acceptable in desegregating urban school sys

tems” (p. 24).

First, southern school boards—and these school boards—

have used not merely manipulative practices within con

tiguous zones but also non-contiguous zones and busing

to achieve segregation. If the measure of desegregation

devices is to be determined by those devices previously

used to segregate, then non-contiguous zones and busing

are included.

6

Second, there is no doctrinal, logical or practical reason

why the roster of desegregation devices should be mea

sured by that of segregation devices. So far as we are

aware, it has never been supposed that the remedial means

of a court of equity were those used by a malefactor in

creating the situation that requires remedying.

(6) It is not only, however, the Government’s reasoning

that troubles us, but the consequences to which it inevitably

leads:

First, as we have said in paragraph (3), supra, the

Government’s vague and elastic “ standards to he applied

in fashioning remedies for state-imposed segregation”

(p. 8) will unquestionably produce another desolating,

wasteful and protracted era of school desegregation

litigation. We had hoped that this Court’s decision in

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 (1969); and Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970), were meant to end that sort of

thing.

Second, standards of this sort cannot he fairly and uni

formly administered. In practice, they boil down to the

disposition of the school hoard, or local district judge, or

the sitting panel of the court of appeals. Experience in

the Fifth Circuit in the past year demonstrates the effect

of standards such as the Government proposes. The Gov

ernment’s description of the Fifth Circuit jurisprudence

at pp. 19-20, 25-26, suggests a sort of consistency that the

cases entirely lack. In the Fifth Circuit, as we have shown

in petitioners’ brief in No. 436, the degree of desegregation

ordered varies from panel to panel.

Third, in the last analysis, as the Government admits on

p. 26, its “ standards” amount to nothing more than a

promise of judicial review of the “good faith” of school

officials. Sixteen years of school desegregation litigation

7

since Brown teach the delusiveness, the utter futility of

any such approach to desegregation.

(7) This Court should order that the schools he desegre

gated by declaring that each black child in Mobile and

Charlotte-Mecklenburg must he assigned to a school which

is not a racially identified “black” school. See para. (2),

supra. Judge McMillan’s order on Nos. 281 and 349 should

be approved as a practicable plan found effective to achieve

this result in Charlotte-Mecklenburg; and the judgment of

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in No. 436

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Geeenbeeg

J ames M . N abrit, III

M ichael D avidson

N orman J . Ch ach k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam S tein

Chambers, S tein , F erguson & L anning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. 0. P earson

203V2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

A nth o n y G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

V ernon Z. Crawford

A lgernon J. Cooper

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Attorneys for Petitioners and

Cross-Respondents

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. °9@ *> 219