Rodgers v US Steel Corp. Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

March 8, 1976

78 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rodgers v US Steel Corp. Appellants Brief, 1976. 051d7cdb-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/92726273-2371-4b4c-954a-5c3a5cfcff22/rodgers-v-us-steel-corp-appellants-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

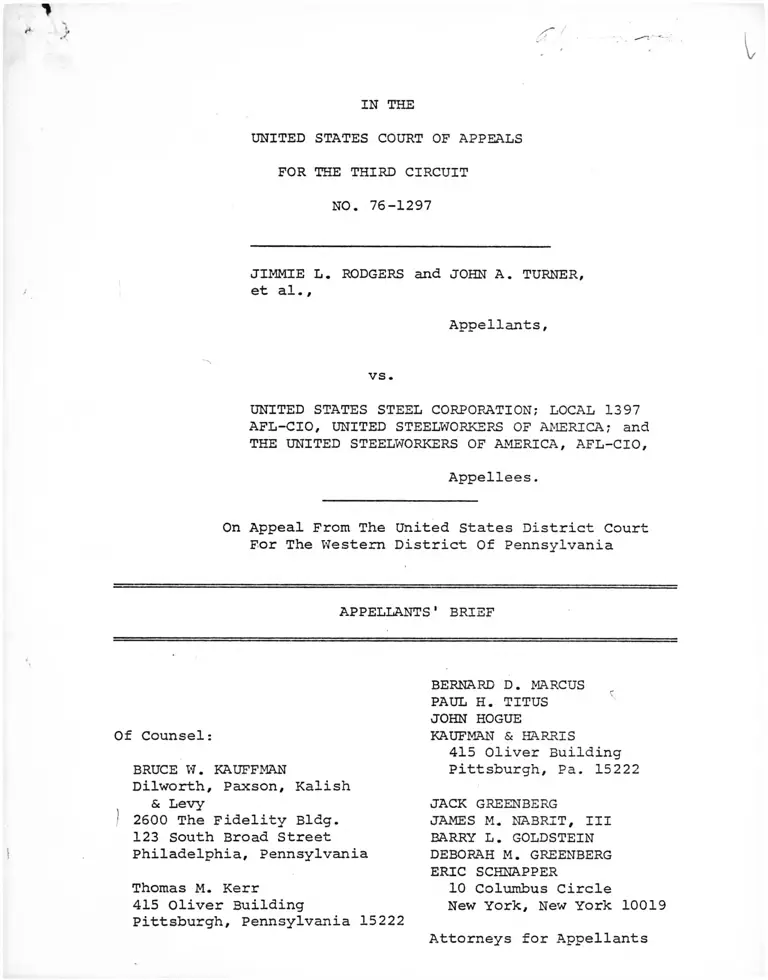

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1297

JIMMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER,

et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION; LOCAL 1397

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA; and

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Pennsylvania

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

Of Counsel:

BRUCE W. KAUFFMAN

Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish

& Levy

' 2600 The Fidelity Bldg.

123 South Broad Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Thomas M. Kerr

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222

BERNARD D. MARCUS

PAUL H. TITUS

JOHN HOGUE

KAUFMAN & HARRIS

415 Oliver Building

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

<* \s

INDEX

Page

Issues Presented For Review ...................... 2

Statement of the Case ............................ 3

Jurisdiction ..................................... 12

Argument ......................................... 17

I. The District Court Erred As a Matter

Of Law And Abused Its Discretion In

Approving the Back Pay Tender Offers .... 17

A. The Requirement of a Hearing

on Fairness and Adequacy .......... 19

B. The Standards For a Determination

of Fairness and Adequacy .......... 27

C. The Unlawful Practices of the Company and the Union, Resulting

Economic Harm and the Insuf

ficiency of the Consent Decree

Remedy ............................ 29

1. Liability .................... 30

2. Inadequacy of Injunctive

Relief Under the Consent

Decree ....................... 34

a. Seniority Relief ........ 34

b. Affirmative Action for

Trade and Craft Jobs

and Testing ............. 38

3. Inadequacy of Monetary Relief

Under Consent Decrees ........ 40

II. Certain Aspects of the Proposed

Waivers Are Invalid As A Matter

of Law ................................. 44

■III. The District Court Erred In Approving

The Notice of Rights, etc., E.E.O.C.

Letters, and Back Pay Tender

Procedures ............................. 54

Page

A. The Notice of Rights and Related

Documents ......................... 54

1. Intelligibility of the

Notices, etc.................. 54

2. Bias in the Notices, etc...... 56

3. Substantive Content .......... 57

B. The E.E.O.C. Letters .............. 59

C. Procedure and Opportunity for

Consultation With Counsel .......... 61

1. 45-Day Limit ................. 62

2. Availability of Free Counsel .. 65

3. One-Step Procedure ........... 67

CONCLUSION ....................................... 70

•>

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Ace Heating & Plumbing Co. v. Crane Co.,

453 F.2d 30 (3rd Cir. 1971).......................... 18

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)....18, 24

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)..... 17

Balias v. Symm, 494 F.2d 1167 (5th Cir. 1974)...........

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543 549 (5th Cir.

1975)................................................

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 311 F.2d 107 (4th Cir.

1962)................................................

Bryan v. Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co., 494 F. 2d 799, 803

(3rd Cir. 1974)......................................

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 339 F. Supp.

1108, 1125 (N.D. Ala. 1972) aff'd per curiam 476 F.2d

1287 (1973)..........................................

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Corp., 373 F. Supp. 526 530-35

(E.D.Tex. 1971)......................................

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541

(1949) .......... ...............................12, 13,

Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975).....

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Co., 421 F.2d 880

(5th Cir. 1970)

Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp., 338 U.S. 507

(1950) ...............................................

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 817

(5th Cir. 1974)......................................

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156, (1974).....

Ford v. United States Steel Corporation 520 F.2d 1043,

1056-57, as clarified 525 F.2d 1214(5th Cir. 1975)...

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974)......................................

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. 44 U.S.L.W. 4356 ■

(March 24, 1976)................................ 18, 33,

Gillespie v. U.S. Steel Corp., 379 U.S. 148 (1964)......

PAGE

20, 25

33, 50

48, 49

16

30

16

22

33

30

14, 15

12

14

32

12, 14

23, 24

32, 37

41, 51

12, 15

i

PAGE

Girsh v. Jepson, 521 F.2d 153 (3rd Cir. 1975)........... 18, 27

Greenfield v. Villager Industries, Inc. 483 F.2d 824

(3rd Cir. 1973)...................................... 18

Gulf & Western Indus., Inc. v. Great A.&P. Tea Co., 476

F.2d 687 (1973)...................................... 16

Hackett v. General Host Corp., 455 F.2d 618 (3rd Cir.

1972) ................................................ 16

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940).................... 20

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870, 879

(6th Cir. 1973)...................................... 33

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454

(1975)............................................... 33

Jones v. Diamond, 519 F.2d 1090 (5th Cir. 1975)......... 16

Jurinko v. Wiegand Co., 477 F.2d 1036, 1046 (3rd Cir.

1973) , vac. on other grounds 414 U.S. 970 (1973)

reinstated 497 F.2d 403 (3rd Cir. 1974).............. 24

Kahan v. Rosenstiel, 424 F.2d 161 (3rd Cir. 1970) cert.

denied, 398 U.S. 950 (1970).......................... 18, 19, 22

LaChapelle v. Owens-Illinois, 513 F.2d 286, 288 n.7 (5th

Cir. 1975) . . .......................................... 23

Local 189 United Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) cert, denied 397

U.S. 919 (1970)...................................... 33

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company, 474 F.2d 134, 138 n.l

(4th Cir. 1974)...................................... 32

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co. 339 U.S.

306 (1950)........................................... 20

Omega Importing Corp. v. Petri-Kine Camera Corp., 451

F.2d 1190 (2d Cir. 1971)............................. 16

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co. F.2d (Nos. 75-1259-63,

Feb. 23, 1976, 4th Cir.)............................. 41

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company, 494 F.2d 211,

260-63 (5th Cir. 1974)....................... 24, 30, 33, 35, 41

Phelan v. Middle States Oil Corp., 210 F.2d 360, 364

(2nd Cir. 1954)...................................... 18

Philadelphia Elec. Co. v. Anaconda American Brass Co.,

42 FRD 324, 327-28 (E.D.Pa. 1967);................... 19

ii

PAGE

Price v. Lucky Stores, Inc., 501 F.2d 1177 (9th Cir.,

1974) ................................................. 16

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 798-800

(4th Cir. 1971).......................................

Rodgers v. U.S. Steel Corp., 508 F.2d 152, cert, denied,

46 L.Ed. 50 (1975)................................ 5, 12,

Rogers.v. International Paper Co. 510 F.2d 1340, 1335

(8th Cir. 1975)...................................... 32,

Rosen v. Public Services Gas & Electric Co. 477 F.2d 90,

95-6 (3rd Cir. 1973)..................................

Sagers v. Yellow Freight System, Inc., No. 74-3617

(5th Cir. April 2, 1976) slip op. at 2715............. 23

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103, 114

(5th Cir. 1975)....................................... 35

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1, 15 (1971).......................................... 52

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., C.A.

No. 74-P-339, N.D. Ala................................ 4, 28

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 63

F.R.D. 1 (N.D.Ala. 1974), aff'd 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir.

1975) ; cert pending, U.S. Supreme Court

No. 75-1008....................................... 5, 28, 33, 36

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652,

658-9 (2nd Cir. 1971)................................. 30, 33

33

16, 67

33, 35

24, 41

iii

PAGE

United States v. Hayes, 95 F.2d 1938

(5th Cir. 1969) ......................... 15

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F. 2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973) ............ 33

United States v. Schiavo, 504 F.2d

(3rd Cir. 1974) ......................... 13 , 14

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

371 F.Supp. 1045, 1055-56 (N.D. Ala.

1973), vac. and rem. on other grounds,

520 F. 2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975) .......... 30 , 38 , 41

United States, et al., v. United States

Steel Corp. et al., 5EPD 1(8619 (N.D.

Ala. 1973) (Decree) ..................... 35

Webster Eisenlohr v. Kalodner, 145 F.2d

316 (3rd Cir. 1944), cert, denied 325

U.S. 867 (1945) ........................ 26

Weight Watchers of Philadelphia, Inc. v.

Weight Watchers Int11, 455 F.2d

770 (2nd Cir. 1972) 26

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., 508

F.2d 239 (3rd Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

44 L. Ed. 2d 679 (1975) ................. 17, 23 , 32

Williams v. Mumford, 511 F.2d 363

(D.C. Cir. 1975) , rehearing en banc

denied, 511 F.2d at 371 ................ 16

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

468 F.2d 1201 (2nd Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, 411 U.S. (1973) ............... 22 , 36

Yaffe v. Powers, 454 F.2d, 362

(1st Cir. 1972) ......................... 16

iv

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1291 --- 2' 12

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) --- 2' 16

Labor Management Relations Act of 1947

as amended, 29 U.S.C. §§ 151 et_ seq. .... 3

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 .... 3

Title VII Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C...... 3, 41

Regulations

29 C.F.R. § 1601.196 ............................. 60

29 C.F.R. § 1607 ............................. 39

Other Authorities

F.R. Civ. P. 23 (b) (2) ........................... 2

F.R.Civ.P. 23(e) ................................ 6, 52

3B Moore's Federal Practice, 1(23.02-1, p. 124 .... 26

Wright & Miller - 7A Federal Practice

& Procedure, § 1797, pp.229-230 .............. 19

PAGE

v.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1297

JIMMIE L. RODGERS and JOHN A. TURNER,

et al.,

Appellants,

v s .

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION; LOCAL 1397

AFL-CIO, UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA; and

THE UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Pennsylvania

APPELLANTS1 BRIEF

This appeal is from an order of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, Teitelbaum, j.,

entered March 8, 1976, denying plaintiffs-appellants1 (hereinafter,

"plaintiff") motion for a preliminary injunction and approving a

tender of back pay to certain members of the class represented

by plaintiffs in settlement of their claims in this action for

injunctive and monetary relief from racial discrimination in

employment. This case raises important issues concerning a) judicial

oversight of attempted settlements of F.R. Civ. P. 23(b) (2)

class actions, when those settlements are opposed by the class

representatives; b) the legality of waivers of prospective

relief; and c) the standards of fairness and comprehensibility

of notices and procedures used by defendants in employment

discrimination suits to solicit releases from employees who are

members of the plaintiff class.

Jurisdiction on this appeal is predicated on 28 U.S.C.

§1291 and §1292 (a) (1). Because of the complex and unusual

posture of this case, a more detailed statement of jurisdiction

follows the statement of the case.

Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether the district court erred as a matter of

law and abused its discretion in approving the making of back

pay tenders to members of plaintiffs 1 class?

2. Whether the Court below erred as a matter of law

in approving the submission to plaintiffs' class of the waivers

which they must sign in return for the tendered backpay.

3. Whether the court below applied the wrong legal

standard and abused its discretion in approving the notice of

rights forms, the EEOC letters and the procedures relating

to the backpay tenders?

-2-

Statement of the Case

Plaintiffs are black employees of defendant United

States Steel Corporation ("hereinafter, "USS" or "the company")

and members of the defendant Local 1397, affiliated with

defendant United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO. This action

was commenced by the filing of a complaint on August 21, 1971

seeking injunctive relief and back pay to remedy racial dis

crimination at the Homestead Works of USS. An amended com

plaint was filed on November 22, 1971. The complaint as

amended alleges violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq., the Civil Rights Act

of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981, and the Labor Management Relations

Act of 1947, as amended, 29 U.S.C. §§151 et_ sea. (927a) .

Prior to filing suit, plaintiffs Rodgers and Turner had,

on July 7, 1970, filed charges of discrimination with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission alleging that defendants had

discriminated against them and other black employees. By decision

dated February 1, 1972, the EEOC found that there was reasonable

cause to believe that defendants had violated Title VII.

On April 12, 1974, Honorable Sam C. Pointer, Jr., United

States District Judge for the Northern District of Alabama,

1/signed two consent decrees (30a-63a; 979a-995a)

~L/ This form of citation is to pages of the Joint Appendix.

-3-

tendered in an employment discrimination suit filed that day

by the United States and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission against nine major steel companies (including USS)

and the United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO. The Alabama

case is styled United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., C.A. No. 74-P-339, N.D. Ala. The decree includes an

injunction which purports to remedy systemic racial dis

crimination and sex discrimination in over 200 plants employ

ing more than 65,000 minority and female workers operated by

the nine steel companies, including the Homestead Works of USS.

The consent decrees also provide that the defendant companies

will tender back pay to certain minority steelworkers in return

for the workers' signing waivers of their rights to further

injunctive relief or monetary relief from discrimination which

occurred prior to April 12, 1974, and monetary relief from the

continuing effects of practices which took place prior to

2/April 12, 1974.

2/ By order entered January 1, 1976, the consent decrees

were amended to provide that persons accepting the tender

offers would also waive their claims to injunctive relief from

the post-decree continuing effects of discrimination which

occurred prior to April 12, 1974 (64a-65a)- The district court

denied plaintiffs1 motion to intervene to oppose the amendment,

but permitted them to intervene for the purpose of filing a

Motion to Reconsider (Id..). Plaintiffs' appeal from the denial

of intervention and the amendment of the consent decrees is

pending (5th Cir. No. 76-1067).

-4-

Plaintiffs moved to intervene in the Alabama action for

the purpose of setting aside the decrees on the ground, inter

alia, that the scope of the waivers was unlawful. The Alabama

district court granted intervention but rejected their objections

to the terms of the decree. U.S. v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries.

Inc.• 63 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala. 1974). The Court of Appeals affirmed,

517 F.2d 826 (1975), and plaintiffs have petitioned for certiorari

(United States Supreme Court No. 75-1008).

Subsequent to the entry of the consent decrees, Judge

Teitelbaum issued a series of oral and written orders restricting

communications with potential members of the Rodgers class bv

plaintiffs or their attorneys for the purpose of preventing

discussion of the consent decrees. On January 24, 1975, this

Court granted plaintiffs' petition for a writ of mandamus with

respect to said orders. Rodgers v. U.S. Steel Coro., 508 F.2d

152, cert, denied, 46 L.Ed.2d 50 (1975).

On December 9, 1975, the district court entered an order

granting plaintiffs' motion for class certification and defining

the class as follows:

[F]or purposes of monetary liability or com

pensation of any sort, to include and be limited

to those blacks who have actually worked in United

States Steel's Homestead Works at any time in the

period from August 24, 1971 until May 1, 1973, or

jobs in the unit represented by defendant Local

1397, and, for purposes of injunctive relief, to

include and to be limited to those blacks who have

actually worked in United States Steel's Homestead

Works at any time after August 24, 1971, on jobs in

the unit represented by defendant Local 1397.

- 5 -

11 FEP Cases 1098 (1975). Plaintiffs estimate that their

entire class numbers 1200 persons. Of these, about 570 are

blacks whose date of employment preceded January 1, 1968 and

either are still employed as of April 12, 1974, or retired in

the two years preceding April 12, 1974. It is these members

of plaintiffs' class who would be eligible to receive tender

offers pursuant to the consent decrees ((57a) .

On December 11, 1975, defendants USS and United Steelworkers

of America, together with the eight other steel companies that

were parties to the steel industry consent decrees, filed a

Motion for Approval of Back Pay Release and Notice Forms in the

United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama.

Petitioners sought to intervene as plaintiffs to oppose approval

of the Notice and Release Forms as well as amendment of the

decrees (p. 4 n. 2, supra). The District Court, Pointer, J., in

an order entered January 6, 1976 (64a-65a) , denied intervention

to petitioners and other applicants for intervention who were

parties to pending cases on the ground that they would "have the

opportunity to be heard in the court where such litigation is

pending on the question of whether — or in what form — tender

of back pay and release should be permitted as to such employees

and their class" (70g). Judge Pointer explicitly declined to

authorize the tender of back pay to employees who are class members

in pending litigation (70f-70g).

6

On January 22, 1976, defendants filed in the court

below their Joint Motion to Approve Tender of Back Pay Pursuant

to Consent Decree in U.S. v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,Inc.

(68a-70aa). Those members of the Rodgers' class who ac

cept the proposed back pay tender must waive their claims to

further injunctive or monetary relief and consequently may be

excluded as class members in this suit (9a, 70x-70aa).

On January 26, 1976, without ruling on plaintiffs' re

quest for a Rule 23(e), F.R.Civ.P. hearing, the district court

scheduled an evidentiary hearing for February 17 and 18, 1976

on the questions of whether the tender offer, notice of rights

and release form were fair and adequate and whether further

proceedings would be required (77a-83a) .

On February 4, the district court denied plaintiffs'

request for expedited discovery with respect to the implementation

of the consent decrees and the adequacy of the injunctive relief

provided by them (127a-133a) .

At the February 17 and 18 hearing, petitioners present

ed substantial, uncontradicted statistical, documentary and

testimonial evidence concerning the unlawful employment

practices of the defendants, their liability under Title VII,

the extent of the harm suffered by black workers both in terms

of the denial of job opportunity and in lost earnings, and the

inadequacy of both the injunctive relief provided by the con

sent degrees and the monetary relief defendants propose to

tender (see, pp. 29-43, infra).

7

Petitioners submitted the testimony and written reports

of four experts to establish that even if the tender offers did

constitute a fair and adequate settlement of petitioners' claims,

the proposed notice of rights and release forms which would

accompany the back pay checks could not be understood by most

of the recipients, and that those portions which were easiest to

understand were biased, in the sense that they would tend to

influence the reader to accept the tender offer and sign the

waiver (see, pp. 54 - 57 , infra).

Other shortcomings of the notice and release forms, and

the one-step procedure for sending out checks with the notices

were briefed to the District Court (256a-264a).

Defendants presented no evidence whatsoever with respect

to liability, the fairness and adequacy of the injunctive and

monetary relief for which members of petitioners' class will be

asked to settle, or the comprehensibility and objectivity of the

notice and release forms.

On March 8, 1976, the district court approved defendants'

motion, thereby authorizing the tender in the form previously

proposed by defendants (I. la-19a). At the same time the court

denied plaintiffs' motion to preliminarily enjoin defendants'

tender (id.).

The district court explicitly refused to decide whether

the injunctive relief for which the Rodgers class members are

being asked to settle, _i.e., the relief provided by the consent

8

decrees, provides an adequate remedy for discrimination at

Homestead Works, stating that the question had already been

decided by Judge Pointer and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals

3/

(lla-13a) .

While the district court acknowledged its duty to weigh

the fairness of the back pay proposed to be tendered, again it

relied upon a statement by the Fifth Circuit to support its finding

that an average back pay offer of $649.00 was fair and adequate

(17a), despite plaintiffs' uncontested showing that members of

the class were entitled to an average award of $7,700.00, plus

interest, pension adjustments and front pay (see, pp. 40 - 43 ,

infra).

The court declined to consider the legality of the releases,

insofar as they constitute a waiver of prospective rights to

monetary and injunctive relief ( 12a-13a ) (see pp. 44 - 54 , infra).

The court agreed that the notice of rights and. release

forms could be made more readable and less biased ( 20a-21a)

(see pp. 54 - 57 , infra). Its approval of them was based

principally on the fact that Judge Pointer had approved them

3/ Neither Judge Pointer nor the Fifth Circuit ever had before

them any evidence with respect to employment practices at Homestead

Works, so that, questions of jurisdiction aside, they could not have

made a determination of the adequacy of the relief provided by the

consent decrees to members of the Rodgers class.

9

. i/(19a, 23a-24a) and that drafting a new notice and release

5/form would delay the tender offer (21a). The court did

not agree with plaintiffs' contention that the one-step

procedure for the tender of back pay, that is, the sending of

a check with the notice of rights, was coercive (see pp. 67 - 70,

infra).

On March 11, plaintiffs filed in the district court a

notice of appeal from the March 8 order and filed a motion

for a stay pending appeal and for an expedited hearing in

this Court. By endorsement dated March 16, 1976 this Court

4/ Judge Pointer explicitly limited his approval of the

notice and release forms to tender offers made to employees

who are not parties, class members or potential class

members in pending litigation. The standard of clarity,

comprehensibility and objectivity to be met by notice and

release forms sent to class members in Rodgers, the potential

value of whose claims is much greater and more likely to be

realized than the value of claims not yet the subject of

litigation, must be higher than that applied by Judge Pointer.

5/ The defendants did not move for approval of the tender

offer until January 22, 1976, twenty months after entry of

the consent decrees and five months after affirmance by the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The defendants presented no

evidence of any injury that would result in delaying the

tender offers, to which interest could be added, until a

comprehensible, fair notice could be prepared.

10

denied plaintiffs' motion, noting that the district court

had stated that "plaintiffs' counsel presently possess,

and will continue to enjoy, the unfettered right to

contact and consult with members of the Rodgers class

for the purpose of advising them with respect to the options

presented by the tender." (22a).

Meanwhile, on March 12, 1976, the district court had

entered an order forbidding plaintiffs’ counsel from dis

closing or disseminating to class members information, which

had been revealed in the testimony of Robert Moore, as to

the manner in which the amount of the back pay offer had

been calculated (28a-29a). Plaintiffs, on March 19,

petitioned this Court for a writ of mandamus commanding the

district judge to vacate the March 12 order, and sought a

stay of the order pendente lite, No. 76-1340. On November 26,

after oral argument, this Court.denied the motion to stay

the March 12 order, but, to maintain the status quo until

action is taken on the petition , restrained defendants

from distributing the back pay tender.

11

On March 30, plaintiffs filed a motion to consolidate

the petition for prerogative writs with this appeal. Argument

on the merits of the petition and on the motion to consolidate

was set down for April 9.

Jurisdiction

This Court has jurisdiction to review the lower court's

March 8th order on the consent decree waivers pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1291 as a "collateral" order under Cohen v. Beneficial

industrial Loan Corn., 337 U.S. 541 (1949) and pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) as a refusal of an injunction.

Section 1291 confers jurisdiction to review orders which,

as a practical matter, "finally determine claims of rights

separable from, and collateral to, rights asserted in the

action, too important to be denied review and too independent of

the cause itself to require that appellate consideration be

deferred until the whole case is adjudicated." Cohen v.

6 /Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp. . supra, 337 U.S. at 546.—

Appellants assert that the March 8th order on the consent

decrees is just such an order in the context of this Title VII

litigation. In Rodgers v. U. S. Steel Coro., supra. 508 F.2d

at 159, this court had occasion to consider an otherwise nonfinal

—/ , Tha*\ § 1291 is to be given a "practical rather than technicalconstruction," 337 U.S. at 546, has been reaffirmed often.

ffillespie v. united States Steel Corp.. 379 U.S. 148, 152 (1964)-

Ej.sen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin. 417 U~.S. 156, 170-72 (1974)- see

alSO — ■* Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn. 420 U.S. 469, 478 n. 7 (1975).

12

order barring communication with then potential class members.

It prohibits communication with potential

class members as to the effect of the Alabama

consent decree on their rights in the instant

case, should class action treatment be per

mitted. If by virtue of the order, potential

class members are left uninformed, and sign, releases, pursuant to the Alabama consent decrees,

those releases will undoubtedly be pleaded in the

district court if a class action determination is

made. When looked at from that standpoint, the

finality of the [communication] order for purpose

of the Cohen rule is a close issue.

The collateral finality of an order permitting issuance of the

consent decree releases to members of the class, a_ fortiori,

cannot be seriously questioned.

The Podaers opinion construed the Cohen rule as having

three requisites: (1) "The order must be final rather than

a provisional disposition of an issue;" (2) " [I]t must not be

merely a step toward final disposition of the merits;" and

(3) " [T]he rights asserted would be irreparably lost if

review is postponed until final judgment." 508 F.2d at 159.

The March 8th order is clearly a final, non-tentative adjudi

cation of the issues of whether a Rule 23 (e) hearing is

required, whether the waiver provisions of the consent decrees

are valid and whether the notice and implementation procedures

are proper. Just as clearly, the order concerns rights "not

an ingredient of the cause of action," Cohen v. Beneficial

industrial Loan Corp., supra, 337 U.S. at 547, and "matter[s]

independent of the issues to be resolved in the [underlying]

proceeding," United States v. Schiavo, 504 F.2d 1, 5 (3rd cir.

1974).

13

Finally, the March 8th order "concerned . . . collateral

matter [s] that could not be reviewed effectively on appeal from

the final judgment." Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, supra,

417 U.S. at 171. The rights that appellants assert are denied

by the order are all associated in various ways with the right of

class members who accept relief under the consent decrees to

continue to participate in the prosecution of this Title VII class

action, rather than the non-discrimination rights at issue on

Vthe merits of the case. collateral rights of this character

necessarily and as a matter of law tip the balance of "incon

venience and costs of piecemeal review on the one hand and the

danger of denying justice by delay on the other," Dickinson v.

Petroleum Conversion corp., 338 U.S. 507, 511 (1950), cited in ,

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, supra, 417 U.S. at 171, in

favor of immediate review on appeal. See, e.q., United States8/ -------------

v. Schiavo, supra. Class members who accept relief under the

l/ Thus, the Rodgers court summarized appellants' submissions

concerning the effect of the consent decrees on this litigation

in terms of "the practical effect of impeding [the] efforts to

achieve more beneficial results through a class action instituted

earlier in the Western District of Pennsylvania. This is because

by the time litigation has proceeded to, judgment many of the class

members will have opted out in favor of the relief afforded by the

consent decree." 508 F.2d at 154.

8/ Compare the asserted requirement of a Rule 23(e) hearing with

the requirement that a plaintiff in a stockholder derivative action

deposit security considered on appeal in Cohen v. Beneficial

Industrial Loan Corp., supra, and that respondents in a stockholder

derivative class action be liable for notice costs considered in

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacauelin. supra; in all three cases

(footnote continued)

14

consent decrees face irreparable injury by exclusion from

whatever preliminary and permanent injunctive relief the

remainder of the class obtains through the Title VII action,

until appellants succeed in having the March 8th order reversed.

As a correlative matter, the remaining class members face

irreparable injury if the class action thus decimated can'not

be as effectively prosecuted. The simple fact is that waiting

until final judgment to consider undoing the mischief worked by

the March 8th order as to Title VII litigation rights would be

"too late effectively to review the present order and the rights

conferred by the statute, if it is applicable, will have been

lost, probably irreparably." Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial

Loan Corp., supra, 337 U.S. at 546. Cf. Culpepper v. Reynolds

Metal Co., 421 F.2d 880, 893-95 (5th Cir. 1970); United States

v. Hayes, 415 F.2d 1038, 1045 (5th Cir. 1969). On the other hand,

immediate review does not impose greater inconvenience and cost.

8/ (Continued)

resolution of the issue by the lower court had "a final and irreparable effect on the rights of the parties." Cohen v.

Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., supra, 337 U.S. at 545.

Compare the asserted invalidity of class members' waivers of

their right to sue with the question concerning the right>of

the brother and sister to sue under the Jones Act considered- in Gillespie v. U. S. Steel Corp., supra; in both cases "delay

of perhaps a number of years in having . . . rights determined

might work a great injustice on them, since the claims for

recovery for their benefit have been effectively cut off so long

as the District Judge's ruling stands." 379 U.S. at 153.

Similarly, compare the notice and implementation procedure

questions with the same kind of separable questions in Cohen

and Eisen.

15

The March 8th order expressly denied plaintiffs'

motion for a preliminary injunction to stop the issuance

2/of the tender offer and is thus properly before this Court

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292 (a)(1) as an interlocutory order

"granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving" an

10/

injunction. There is no doubt that for class members who

accept relief offered by the consent decrees the practical

effect, whether right or not, will be exclusion from the class

action and denial of any possibility of obtaining injunctive

11/ 'relief through the class action. The March 8th order is also

tantamount to an order narrowing the scope of whatever broad

injunctive relief the remaining class can obtain. Compare

Hackett v. General Host Corp., 455 F.2d 618, 622 (3rd Cir.

1972); but see, Rodgers v. U. S. Steel Corp., supra, 508

12/

F. 2d 160.

9/ Compare, e.g., Gulf & Western Indus., Inc, v. Great A. & P.

Tea Co.. 476 F.2d 687 (1973) (antitrust case).

10/ See, e.g., Omega Importing Corp. v. Petri-Kine Camera Corp.,

451 F.2d 1190, 1197 (2d Cir. 1971).

11/ See, e.g., Ballis v. Symm, 494 F.2d 1167, 1169 (5th Cir.

1974).

12/ See also, Jones v. Diamond, 519 F.2d 1090 (5th Cir. 1975);

Yaffe v. Powers, 454 F.2d 1362 (1st Cir. 1972); Brunson v.

Board of Trustees, 311 F.2d 107 (4th Cir. 1962); Price v.

Lucky Stores, Inc., 501 F.2d 1177 (9th Cir. 1974); contra:

Williams v. Mumford, 511 F.2d 363 (D.C. Cir. 1975), rehearing

en banc denied, 511 F.2d at 371 (Chief Judge Bazelon and

Judges Robinson, Wright and Leventhal would have granted

rehearing).

16

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW

AND ABUSED ITS DISCRETION IN APPROVING THE BACK PAY TENDER OFFERS

This Court has forcefully articulated the importance of

private suits in the legislative scheme of Title VII:

Suits brought by private employees are

the-cutting edge of the Title VII sword

which Congress has fashioned to fight a

major enemy to continuing progress, strength

and solidarity in our nation, discrimination in employment,

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., 508 F.2d 239, 254,

(3rd Cir. 1975). The Supreme Court, while acknowledging that

"[c]ooperation and voluntary compliance were selected as the

preferred means" for achieving the goal of equality of employ

ment opportunities, has recognized that Congress reposed

"ultimate authority" in federal courts and gave individuals

"a significant role in the employment process of Title VII",

stating:

In such cases, the private litigant not only

redresses his own injury but also vindicates

the important congressional policy against

discriminatory employment practices.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,415 U.S. 36, 44, 45 (1974).

The key question presented by this appeal is whether

defendants, in a private suit brought under Title VII, should

be permitted to buy up the claims of members of the class without

appropriate judicial review of the fairness and adequacy of the

injunctive and monetary relief for which the class members are

being asked to settle. Such a tactic would seriously undermine

17

the ability of private employees to seek redress on behalf of

a class and would defeat the J,make whole" purpose of Title VII.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 44 U.S.L.W. 4356 (March 24,

1976); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

The tender offers approved by the district court will

potentially result in the dismissal or compromise of the claims

of about one-half of the class members. Under these circum

stances, where the class claims of members of the class may be

finally dismissed or compromised, the interests of the class

13/must be protected as required by Rule 23(e), F.R.Civ.P.

While this is not the typical class action settlement situation,

inasmuch as class members will, by accepting the tender offers,

be opting out of the class, the conduct of the case must be

guided by equitable principles. The appropriate standards of

fairness to be applied are no better exemplified than by the

procedure approved by the Supreme Court and this Court for closely

analogous situations as embodied in Rule 23 (e) ; Girsh v. Jepson,

521 F.2d 153 (3rd Cir. 1975) ; Greenfield v. Villager Industries,

Inc., 483 F.2d 824 (3rd Cir. 1973); Ace Heating & Plumbing Co.,

v. Crane Co., 453 F.2d 30 (3rd Cir. 1971); and Kahan v. Rosenstiel,

424 F.2d 161 (3rd Cir. 1970), cert. denied, 398 U.S. 950 (1970).

13/ Even though the dismissal or compromise affects the claims

of only a part of a class, a Rule 23(e) hearing is nevertheless

required. Phelan v. Middle States Oil Corp., 210 F.2d 360, 364

(2nd Cir. 1954).

18

Indeed., the district court recognized its obligation to assess

the tender offer in the light of these standards (16a) . It

failed to do so, however, explicitly declining to review the

adequacy of the injunctive relief provided by the consent

decrees (13a). and essentially relying upon a statement of

the Fifth Circuit to support its finding that an average back

pay offer of $649 was fair and adequate (17a).

Plaintiffs adduced substantial evidence that the injunc

tive and monetary relief provided by the consent decrees was

grossly inadequate to remedy the discrimination suffered by

plaintiffs' class at Homestead Works. Defendants, who, as pro

ponents of the compromise should have borne the burden of demon

strating that the compromise is "fair and reasonable and in the

14 /best interests of all those who will be affected by it," offered

not a shred of evidence in support of it. The district court's

approval of the tender offer in these circumstances was erroneous

and a clear abuse of discretion and should be reversed.

A. The Requirement of a Hearing on Fairnessand Adequacy

Rule 23(e), F.R.Civ.P. requires that district courts

approve any dismissal and compromise of a class action.

15/This rule has been strictly applied to protect absent class

members from unfair, unreasonable settlements which are not in

14/ Wright & Miller - 7A Federal Practice & Procedure, §1797 pp. 229-230.

15/ The rule has been extended to actions which have not been

certified as class actions. Philadelphia Elec. Co. v. Anaconda

American Brass Co., 42 FRD 324, 327-28 (E.D. Pa. 1967); cf. Kahan

v« Rosenstiel 424 F.2d 161, (3rd Cir. 1970) , cert, denied, 398 U.S. 950 (1970). ---- ------

19

their best interests. 3B Moore's Federal Practice, §23.80 [2-l];

cf. Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940); Mullane v. Central

Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306 (1950).

The typical class action settlement presented in a dis

trict court for approval involves a proposed agreement which

has been negotiated by the representatives of all the parties.

This is not the situation before this Court. The proposed

tender offer is the result of negotiations between eight com

panies and three agencies of the federal government (who are not

parties to the Rodgers action) in addition to the defendants U.S.

Steel and the Steelworkers. No representatives of the class were

present at the negotiations which led to the Consent Decrees.

Nor, of course, did any representative of the class approve

the proposed tender offer.

Although this litigation does not follow the usual pattern,

all the reasons for applying the Rule 23(e) standard pertain equal

ly or even more strongly to this action. The Court's obligation

to review the adequacy of the settlement which applies when the

representatives of the class have approved the compromise should

apply even more strongly when only the defendants are the pro

ponents :

[W]hen the settlement is not negotiated by a

court designated class representative the court

must be doubly careful in evaluating the fairness

of the settlement to plaintiffs' class.

Ace Heating & Plumbing Co. v. Crane Co., supra, 453 F.2d at 33.

20

When class representatives join in proposing the settlement

the class members have access to the information and procedures

which produced the proposed settlement. In addition, the

class representatives are charged with the serious responsi

bility of representing the best interests of the class. Here,

the class neither had their representatives present at the

negotiations nor did they have access to the background of the

proposed settlement or to information as to how the many open-

ended provisions of the consent decrees have been implemented

at Homestead Works and the movement of black employees since

the decrees became effective.

Nor can representation by the government be considered

comparable to representation in a private class action. The

government no matter how diligently it prosecutes Title VII

suits does not, as this Court described, have the same interests

as those of private class representatives:

. . . [C]lass suits serve different ends than do

public suits. The Attorney General's prosecution

of a suit is governed by desire to achieve broad

public goals and the need to harmonize public

policies that may be in conflict; practical

considerations such as where limited public re

sources can be concentrated most effectively,

may dictate conduct of a suit inimical to the

immediate interests of the discriminatee, who

presumably seeks full satisfaction of his indi

vidual claim regardless of the effect on other

cases.

Unlike suit by the Attorney General or even

by a "private attorney general," who sues to

protect public rights, the class action seeks

to vindicate the rights of specific individuals,

the class members; and unlike the public action,

for a class action to be maintained the class

representatives must be members of the class,

have claims typical of the class and adequately

represent the interests of absent class members.

21

Bryan v. Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co., 494 F.2d 799, 803 (3rd

Cir. 1974); see Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d

1201 (2nd Cir. 1972), cert, denied 411 U.S. 911 (1973).

The difference between the interests of the government

and the private class representatives is dramatically illus

trated by this case. The government's primary interest was

apparently to negotiate an accommodation with the steel

industry in order to provide a general form of relief to

workers in over 200 plants. The interest of the private class

representatives, and of the district court in approving the com

promise of a class claim, is in a fair, reasonable and adequate

remedy for the certified class at Homestead Works. This particular

interest was not addressed, nor could it be, within the enormous

16/

scope of the industry-wide settlement.

This Court in Kahan v. Rosenstiel, supra, strongly indi

cated that Rule 23(e) applies to the instant case. Kahan was

an action under the Securities Exchange Act to compel the

defendants to increase the amount of an allegedly inadequate

tender offer. After the suit was commenced the defendants,

without negotiating with plaintiff, increased their tender offer.

This Court held that, to the extent that the new offer was

prompted by the pending litigation, a Rule 23(e) hearing was

required,424 F.2d at 169. In Kahan a Rule 23(e) hearing was

16/ In fact, counsel for United States Steel Corporation,

Mr. Scheinholtz, represented that in the determination of

an appropriate back pay award "there was no particular con

sideration of Homestead as a separate entity." (119a).

22

deemed proper even though the defendants had offered the class

members 100 cents on the dollar and asked nothing in return;

that decision applies a fortiori to the instant case, where

the defendants offer nine cents on the dollar (see pp.40-43,

infra) and require in return a sweeping waiver. It would be in

consistent with Rule 23 to permit a defendant in a class action,

absent the most stringent supervision, to buy up the rights of

individual class members without acting through, or negotiating

with the authorized class representative;

Moreover, the characteristics of a Rule 23(b) (2.) as

opposed to those of a 23(b)(3) class action require a careful

and extensive review of the fairness and adequacy of the tender

offers. "The cohesive characteristics of the class are the vital

core of a (b)(2) action," Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co.,

508 F.2d 239, 251 (3rd Cir. 1975), cert. denied 44 L.Ed.2d 679

(1975), and accordingly class members may not opt out of a Rule

23(b)(2) action, at least after it is certified. Wetzel v.

Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., supra at 248-49; Sagers v. Yellow Freight

System, Inc., No. 74-3617 (5th Cir. April 2, 1976), slip op. at

2715; LaChapelle v. Owens-Illinois, 513 F.2d 286, 288 n.7 (5th

Cir. 1975); cf. Ford v. United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d

1043, 1056-57, as clarified 525 F.2d 1214 (5th Cir. 1975).

If the Court affirms the district court's approval of

the tender offer, those class members who accept will, in many

cases, effectively opt out of the Rodgers action. Any such

drastic departure from the established class action law designed

to protect the "cohesiveness" of the (b)(2) action must, if it is

lawful at all, be based on a careful review of the fairness and

adequacy of the proposed settlement.

2 3

Finally, 23(e) should be scrupulously followed in

light of the fact that the method by which the award of back

pay was calculated under the consent decrees is antithetical

to an appropriate determination by the courts in contested

litigation. Briefly, the parties to the consent decrees

agreed on a final amount for all minorities and females in

over 200 plants throughout the United States. After the amount

was divided by Company and by plant it was subdivided among the

black workers at the Homestead plant.

It is now well established that a major purpose of Title

VII is to make workers "whole" for losses suffered as a result

of discrimination; a back pay award must be designed to accom

plish this end. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

418-22 (1975); see also Rosen v. Public Services Gas & Electric

Co., 477 F.2d 90, 95-6 (3rd Cir. 1973), Jurinko v.-Wiegand Co.,

477 F.2d 1036, 1046 (3rd Cir. 1973), vac. on other grounds, 414

U.S. 970 (1973), reinstated 497 F.2d 403 (3rd Cir. 1974). The

award of back pay in contested litigation, whether by a judicial

judgment or supervision of a proposed settlement is determined

by a calculation of the individual economic harm suffered or a

reasonable approximation of individual or class harm based on

the discriminatory practice. Ford v. United States Steel

Corporation, supra at 1052-56; Pettway v. American Cast Iron

Pipe Company, 494 F.2d 211, 260-63 (5th Cir. 1974).

24

When the method of determining the proposed award in

settlement is at great variance with the established purpose

and procedure of Title VII as it is here, there is a special

burden on the court to scrutinize the fairness, adequacy and

reasonableness of the award.

This Court's decision in Ace Heating & Plumbing Company

v. Crane Company, 453 F.2d 30 (1971) is particularly instructive.

In this class action, certified pursuant to 23(b)(3), class

members were sent an "opt-out" notice along with a notice of

the proposed settlement. The notice categorically stated that

those who did not opt out would be subject to a judgment which

is "final and unappealable". The question before the Third

Circuit was whether class members who did not opt out could

appeal from the entry of the settlement.

The Third Circuit stated that "perhaps" the drafters

of Rule 23 did not envision a situation where the decision

to opt out occurred when the class member knew precisely the

terms of settlement. Although noting that "in such a case

there may be less need [for the courts] to police settlements,

since the question of fairness is left to the informed choice

of the class members", the Court emphatically maintained that

the full protection of Rule 23 applied. This included the right

to appeal: "a serious public policy question would be presented

if the notice was construed to require a waiver of the right to

appeal as a condition of opting in", id. at 32-33.

Under former Rule 23, revised in 1966, defendants in

a "spurious" class action could enter into a settlement with

members of the class without court approval. But cf. Webster

Eisenlohr v. Kalodner, 145 F.2d 316, 325-26 (3rd Cir. 1944),

cert, denied 325 U.S. 867 (194S). At least one court has

12/applied this rule to a non-certified (b)(3) action under the

present Rule 23. Weight Watchers of Philadelphia, Inc, v.

Weight Watchers Int*1, 455 F.2d 770 (2nd Cir. 1972) . The Weight

Watchers case is clearly distinguishable from Rodgers and in fact

indicates the need for active participation by the district court

to protect class members from overreaching by the defendants.

18/Weight Watchers involved negotiation prior to class certification

19/between businesses, who were all represented by counsel, with

relative equality of bargaining power, and plaintiffs' counsel

was permitted to participate in the negotiations. Here the de

fendants seek to make'"take it or leave it" offers of settlement

(which resulted from secret negotiations) to laymen in a manner

which severely limits their ability to receive legal counsel and

to be informed of their options. This present situation requires

the protection of Rule 23(e) to safeguard the interests and civil

rights of class members.

17/ "The (b)(3) class action is the old spurious class action

become mod." 3B Moore's Federal Practice, 1(23.02-1, p. 124.

18/ The Second Circuit specifically stated that the decision

did not pertain to a certified class action. Weight Watchers

of Phila. v. Weight Watcher Int'l, supra at 773, n.l.

19/ The putative class contained the franchisees of the

defendant.

26

B. The Standards for a Determination of Fairnessand Adequacy

The district court, while holding that a normal 23(e)

hearing was not required (15a ), purported to subject the

proposed compromise to the standards for such hearings an

nounced in Girsh v. Jepson, 521 F.2d 153, 157 (3rd Cir. 1975).

The hearing and decision of the court, however, fall far short

of these standards.

(1) Girsh holds that the court must afford opponents

of a compromise "an adequate opportunity to test by discovery

the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed settlement."

521 F.2d at 157. The district court, however, refused to per

mit full discovery as to what effect the consent decrees had

had since their adoption in 1974, as to whether those decrees

had indeed remedied the alleged discrimination, or whether the

2 0/defendants were in compliance with the decrees.

(2) Girsh requires that the fairness of a monetary

settlement be determined by comparing it with "the best

possible recovery" and the likelihood that the litigation

would succeed. 521 F.2d at 157. The district court, however,

expressly stated that it considered and approved the compromise

20 / The plaintiffs sought expedited answers to interrogatories

designed to determine whether blacks were provided an opportunity

to move to previously all-white or predominantly white jobs since

the consent decrees became effective in August 1974, and whether

the testing practices of defendants since that date complied with

Title VII, (101a-108a).

The district court denied plaintiffs the right to take such dis

covery on an expedited basis so that it would be available for

the February 17-18 hearing (127a-128a).

27

"[r]egardless of any likelihood of defendants' liability or

the potential size of plaintiffs' possible monetary recovery"

(17a). The court acknowledged disparity between the back

pay offer and the actual liability, but assumed it was com

pelled to approve any offer other than "a mere pittance" even

if it was only a small fraction of the actual liability.

(3) Under the proposed waiver employees would lose

their rights to seek additional injunctive relief over and

above that provided by the consent decrees. Plaintiffs ex

pressly objected to the waiver on the ground that the injunctive

relief provided by those decrees at Homestead Works was neither

fair, adequate, nor effective (94a-100a). The district

court refused to even consider this contention, asserting that

the adequacy of the injunctive relief at Homestead had already

been, decided by Judge Pointer in Alabama (11a). That assertion

21_ /is entirely incorrect.' Nothing in Judge Pointer's decision

intimates any approval of the injunctive relief in this case.

Indeed, Judge Pointer has never had or sought any information

whatever regarding the nature of the discrimination which

exists at Homestead Works. Judge Pointer does not know, and

Judge Teitelbaum refused to allow discovery to permit him to

learn, whether the consent decrees have been obeyed at Homestead

Works, how the broad language has been implemented, or how many

21/ United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

6 3 F.R.D. I (N.D. Alai 1974) ; U.S. v~. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc. No. CA 74-P-339-S (Memorandum Opinion,

January 6 , 1976) , (70d) .

28

black employees, if any, have been able to transfer into

previously white departments or jobs since the consent

decrees were signed two years ago.

(4) Rule 23(e) expressly requires that, prior to

approval of a compromise, the court must notify the affected

class members and give them an opportunity to be heard.

Girsh requires the court considering a decree to take into

account "the reaction of the class to the settlement." 521

F.2d at 157. These requirements serve a variety of salutary

purposes; in a case such as this they assure that minority

employees, who have unique first hand knowledge of the problems

of discrimination and the operation of the consent decrees, can

make known their views as to the deficiencies of the decrees

and that the court will rely on that information. The district

court, however, refused to give the affected employees notice

about and an opportunity to object, comment or to seek clari

fication of the proposed tender offer.

C. The Unlawful Practices of the Company and

the Union, Resulting Economic Harm and the

Insufficiency of the Consent Decree Remedy

The plaintiffs presented substantial, uncontradicted

evidence concerning the unlawful employment practices of the

defendants and their liability under Title VII, the extent of

the harm suffered by black workers both in terms of the denial

of job opportunity and in lost earnings, ag^the inadequacy of

the relief provided by the consent decrees”

22_/(The district court's characterization of plaintiffs' evidence as "ex parte" (16a-17a) is misleading. The evidence was presented

in open court, and defendants, who had as much notice as did

plaintiffs that the February 17-18 hearing was to be an evidentiary one, simply chose to introduce no evidence.

29

1. Liability

Until August, 1974, the Company had a fractionalized

seniority system which required the forfeiture of accumulated

seniority whenever an employee transferred job sequences

23 /(called "lines of progression" or "LOPs").

This seniority

system, when superimposed on initial job assignments made on

racial lines, effectively "locks" blacks into the lowest-pay-

24/ing and most menial jobs. The lock-in effect of the seniority

system was exacerbated in this case by the fact that vacancies

? S /m one department were pot posted in other departments.

23_/ The requirement that an employee forfeits seniority upon

transfer has aptly been termed "seniority suicide". Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543, 549 (5th Cir. 1975).

The production and .maintenance jobs at Homestead Works

are divided into approximately eleven departments, 80 seniority units and 300 lines of progression(798a-808a). Until 1974 employee

promotion and regression was primarily governed by "job seniority",

the accumulated years of service an employee worked in a particular job. If an employee transferred LOPs he forfeited his

accumulated job seniority and for purposes of promotion and

regression was treated as a new employee in his new LOP.

2aJ The workings of a discriminatory seniority system is described in several cases involving steel plants. United

States v. Bethelehem Steel-Corp., 446 F.2d 652, 658-59, (2nd

Cir. 1971); Bush v. Lone Star Steel Corp., 373 F.Supp. 526,

530-35 (E.D. Tex. 1971); United States v. United States Steel

Corp., 371 F.Supp. 1045, 1055-56 (N.D. Ala. 1973) vac. and rem. on other grounds 520 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975).

25/ See px-18, Deposition of John Owens, Supervisor of Employ-

ment, (736a). Of course, without job posting blacks who were

not in the basically all-white departments would be unable to

bid for jobs in white departments even if they desired to commit

"seniority suicide". See, e.g., Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 248-49 (5th Cir. 1974T:

30

The statistical representation of the racial

allocation of jobs graphically demonstrates the racially

adverse consequences of the seniority practices at Homestead:

Blacks are disproportionately assigned and "locked-in" to the

26/lower-paying departments and lines of progression.

Defendants have not yet acceded to plaintiffs' requests

for information showing the relative treatment accorded blacks

and whites prior to July 2, 1965, the effective date of Title

VII. However, it is apparent that defendants continued to dis

criminate against blacks in initial job assignment and entry

into trade and craft jobs long after that date.

The Company's daily employment sheets for the period

July 1965 through September 1970 show that virtually no blacks

were hired into other than laborer jobs in the least desirable

departments or seniority units while most whites were hired

directly into higher paying jobs or into laborer jobs in de

partments or units holding greater opportunity for advancement

(902a-919a). The Company's personnel director has admitted that,

with one exception, the non-laborer jobs into which whites were

hired require no special education or previous experience. (6 6 8a-

675a, 690a-695a).

The almost-total exclusion of blacks from the high-

paying Trade and Craft jobs is perhaps most telling. The

following chart indicates that blacks have occupied less than

1% of Trade and Craft positions'from 1967 through 1973 (921a-

2 ft/ The plaintiffs submitted computer printouts which detailed

the differential racial job assignments and pay rates. (772a-

901a). see the summary of disparate racial assignment by

department (920a).

[footnote cont'd]

31

925a).

# BLACKS # WHITES

1967 3 960

1971 6 1044

1973 10 1099

The Company's testing program as well as its seniority system

served to limit black enrollment in the apprentice and on-the

, • • 12/3 0b training programs for craft positions. The Company uses

the Wonderlic Test in the apprentice selection process. Courts

have repeatedly found that this test, as Judge Thornberry

28 /phrased it, is "race-oriented".

Finally, the plaintiffs were prepared to call class

members to testify to particular acts of discrimination and to

the manner in which they were affected by the systemic discrim

ination. The district court did not permit their testifying

in open court, but did permit the submission of the depositions

26/ [footnote cont'd]

This Court has recognized that "statistics" are particularly

appropriate in Title VII class actions where it is the aggregate

effect of a company's policy on the class which is important",

(footnote omitted) Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., 508

F . 2d 239, 259 (1975T:

27/ The Company uses a "battery" of employment tests for select

ing apprentices or on-the-job trainees. (See PX-13, Response of

Defendant Company to Plaintiffs' First Interrogatories, No. 69*695a, 745a).

28/ m— Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398, 412 (5th

Cir. 1974), rev. and rem. on other grounds 44 U.S.L.W. 4355 (1976); Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company, 474 F.2d 134, 138 n.l (4th Cir.

1974), vac. and rem. on other grounds, 422 U.S. 405; Rogers v. Inter- national Paper Company. 510 F.2d 1430 (8th Cir. 1975), vac. and rem. on

other grounds* 46L.Ed.2d 29 (1975) ; Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber

Co., 494 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1974).

32

of class members.

If, after a trial on the merits, the district court finds

that defendants have discriminated against plaintiffs' class in the

manner described above, plaintiffs will be entitled to relief which

will enable class members to reach their "rightful places," i.e.,

the jobs they would have held but for discrimination, as quickly as

30/the dictates of "business necessity" permit, affirmative action

31/with respect to certain categories of jobs, back pay to make them32/

financially whole, and, if the evidence warrants it, punitive 33/

damages. Those members of plaintiffs' class who accept the tender

offers will be denied any injunctive relief beyond that afforded by

the consent decrees entered in U.S. v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 63 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala. 1974), aff'd, 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir.

1975) and any monetary relief beyond that tendered.

29/

29/ See e.g., PX-75, Deposition of William Vick (discrimination

in initial placement, transfer, promotion); PX-78, Deposition of

Donald D. Peterson (discrimination in selection for craft position);

PX-76, Deposition of Jackson Goodman (historical patterns of dis

crimination) . Because of their length, these depositions have not been reproduced in the Joint Appendix.

30/ Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 44 U.S.L.W. at TJ60-4361 n.21, 4362 n.28, 4363; Unxted States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp♦, 446 F.2d 652, 660-62 (2nd Cir. 1971); Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 798-800 (4th Cir. 1971) Local 189 United Paper-

makers & Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) ,

cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970); Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co., 494 F.2d 211. 248-49 (5th CirT 1974); Head v. Timken Roller

Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870, 879 (6th Cir. 1973); Rogers v. Inter

national Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340, 1355 (8th Cir. 1975), vac. and rem. on other grounds, 46 L.Ed.2d 29 (1975).

3 1/ Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 339 F.Supp. 1108,

IT25 (N.D. Ala., 1 9 7 2 ) , aff'd per curiam 476 F.2d 1287 (1 9 7 3 ) ; United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 378 (8th Cir. 1 97 3) .

32/ Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

33/ Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975).

33

2 Inadequacy of Injunctive Relief Under Consent Decrees

a. Seniority Relief

The job seniority system which was in effect

prior to the consent decrees served to lock blacks into the

less desirable seniority units to which they were discrimina-

torily assigned, because to transfer would have resulted in

loss of protection from layoff and the other advantages which

seniority affords as well as a loss of pay, since transferring

meant starting at an entry level job.

The consent decrees provide for the use of plant

continuous service as the measure of continuous service for

virtually all seniority purposes. However, there remain

numerous impediments to a black employee’s use of plant

seniority to attain his rightful place. The decrees establish

a three-step bidding procedure. If a vacancy occurs on the

second job in a job sequence, then that vacancy is filled by

the senior employee on the first job in the sequence. The

bottom or entry-level job is then filled by the senior employee

in the department who bids on that job, regardless of whether

his experience particularly qualifies him. Finally, the

bottom job left vacant in the department is filled by the

senior employee in the plant. It is only this last job that

is posted for bidding plant-wide (46a, 720a-723a). This tedious

time-consuming process for allowing black employees to move to

34

their rightful place contravenes at least three specific

necessary forms of relief which have been mandated by the

Courts: advance-level entry (transfer to a job above entry-

level in a job sequence), job skipping (jumping over certain

jobs, experience in which is not necessary for successful

performance of higher jobs in a job sequence), and plant-wide

posting of vacancies. See, e.g., Pettway v. American Cast

Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 248-49 (5th Cir. 1974); Stevenson

v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103, 114 (5th Cir. 1975);

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340, 1335-57 (8th

Cir. 1975), vac. and rem on other grounds, 46 L.Ed.2d (1975).

In addition, the seniority relief afforded in the

decrees ignores all the innovative relief designed to

terminate the unlawful continuing effects of discrimination

and speed black employees to their rightful place which was

established in the Title VII case involving the Company's

24/Fairfield Works. Some of the important seniority relief

provisions established by the Fairfield Works decree but not

by the consent decrees include the following:

(1) The right of an employee to exercise his plant

seniority to "bump" a junior employee one job

above his job in a job sequence during a re

duction in force, (Section 4(b)(1);

3 4 / United States, et al., v. United States Steel Corp.,

et al., 5 EPD 1(8619 (N.D. Ala. 1973) (Decree) ; the citations

in the paragraph above are to the sections of that Decree.

35--

(2) The right of an employee on a recall from a

reduction in force to "exercise his seniority

to step up one job above the highest job he

held on a permanent basis prior to the re-

35/duction," (Section 4(b)(2);

(3) The right of an employee to carry his plant

seniority from one plant to another plant

where this is necessary to terminate the

effects of past discrimination, (Section

4(e) (f) (g) .

Thus, as the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recognized

in United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d

826 (5th Cir. 1975), the consent decrees fail to include par

ticular provisions which would give effect to the Congressional

mandate to afford "the most complete relief possible" in Title

VII actions.

Many of the critical decisions bearing on the

effectiveness of the decrees — such as whether to revise

seniority units and pools, whether to establish two-step

bidding, whether to alter temporary vacancy practices and

whether to amend transfer provisions generally — are left

_35/ Consent Decree I, Paragraph 4(a)(1)(b) (III.la., p.28)

provides that "the sequence on a recall shall be made'. . .

so that the same experienced people shall return to jobs in

the same position relative to one another that existed prior

to the reductions." This is the very system which the Second

Circuit mandated the District Court to remedy in Williamson v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d 1201 (2nd Cir. 1972H

36

to the local Implementation Committees. As of this date, almost

two years after the entry of the decrees, the Implementation Com

mittee at Homestead Works has failed to establish two-step bidding

for any jobs or to alter temporary vacancy practices. (724a).

Hooker jobs to which blacks

have traditionally been assigned and which provide the best train

ing for Craneman jobs, which have traditionally been held by whites,

continue to be in separate promotional sequences, so that a hooker

cannot move up to the job of craneman except by starting in an

entry level job in another promotional sequence. (696~715a, 7 9 5a-

835a).

In its recent decision in Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., supra, the Supreme Court has stated in the clearest of terms

the critical importance of granting complete seniority relief to

victims of employment discrimination:

The Reports of both Houses of Congress indicated

that "rightful place" was the intended objective

of Title VII and the relief accorded thereunder . . . .

[R]ightful place seniority, implicating an

employee's future earnings, job security and

advancement prospects, is absolutely essential

to obtaining this congressionally mandated goal.

44 U.S.L.W. at 4361 n. 21 (emphasis in original);

[T]he issue of seniority relief cuts to the very

heart of Title VII's primary objective of eradi

cating present and future discrimination in a

way that back pay, for example, can never do'.

"[S]eniority, after all, is a right which a

worker exercises in each job movement in the

future, rather than a simple one-time payment

for the past."

Id. at 4362 n.28.

The gross inadequacy of the seniority relief provided by

the consent decrees, when measured against the Franks standard, is

in itself sufficient reason to disallow the making of the tender

offers. 37

b. Affirmative Action for Trade and Craft Jobs and Testing.

An analysis of defendants' records shows that as late

as 1973, blacks were almost totally excluded from trade and

craft jobs, the highest-paying, most prestigious jobs in the

plant, holding ten out of 1109 such positions (921a-925a)

The consent decrees do not establish "goals and

timetables for the placement of blacks in trade and craft

jobs but do establish "implementing ratios," i.e., the ratios

at which blacks, Spanish—surnamed Americans, and women com

bined are to be hired or promoted. These implementing ratios

f^r behind the ratios established for blacks alone in the

^^i^fisld WorKs case. United States v. United States Steel

Corp., 5 EPD 118619 (N.D. Ala. 1973) (Decree, Section 7).

The decrees provide that within 120 days of the entry

date,.April 11, 1974, the Implementation Committee at each

plant shall establish goals and timetables for minority re

presentation in such jobs. Defendants have given plaintiffs

licting information as to whether such goals or timetables36/

have been established at Homestead Works. Thus, a class

member to whom a tender offer was made would, if he accepted

the offer, waive his right to seek relief from the discrimina

tory exclusion of blacks from trade and craft jobs without

knowing what relief was to be provided under the consent decree.

36/ While United States Steel's Supervisor of Employment and

Placement, John owens, who is a member of the Homestead Imple

mentation Committee, testified that no such goals had been

established, (see PX-18, Deposition of John Owens, (756a-766a))

Pls-iritiffs have been advised by letter dated 2/13/76 from defendants' counsel that goals were established and are on file with the

United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

(926a). Not only do the affected class members in the Rodgers

38 [footnote continued]

One of the principal roadblocks to black entry into

the apprenticeship programs which lead to trade and craft jobs

has been the use of discriminatory, non-job related tests.

Section 11 of the Consent Decree I requires that all selection

procedures which have a disparate impact on minorities be

validated in accordance with the EEOC's Guidelines on Employ

ment Selection Procedures," 29 CFR §1607 (52a-53a) .

The Company admits that it is still using tests for admission

into apprenticeship programs. It has refused to disclose

either the tests it is using or any validation studies.

(745a-746a).

Section 10(g) of Consent Decree I provides that

minority applicants for trade and craft jobs or apprentice

ship programs "shall not be required . . . to possess

qualifications which exceed the minimum criteria applied to

white male applicants, who, since a job was established as a

craft in the plant,.have been admitted and are successfully

performing the requirements of the job . . . " (52a).

All employees who wish to become a motor inspector or mill

wright must pass tests for admission to an apprenticeship

program, then successfully complete an apprenticeship

(754a). The Company's personnel director has admitted,

that at Homestead V7orks there are motor

36/ [footnote cont'd]

case not know what these goals are and whether they are