Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Motion and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Motion and Brief Amici Curiae, 1947. 24e39d59-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/928d5845-e129-4eea-933b-a42804879825/takahashi-v-fish-and-game-commission-motion-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

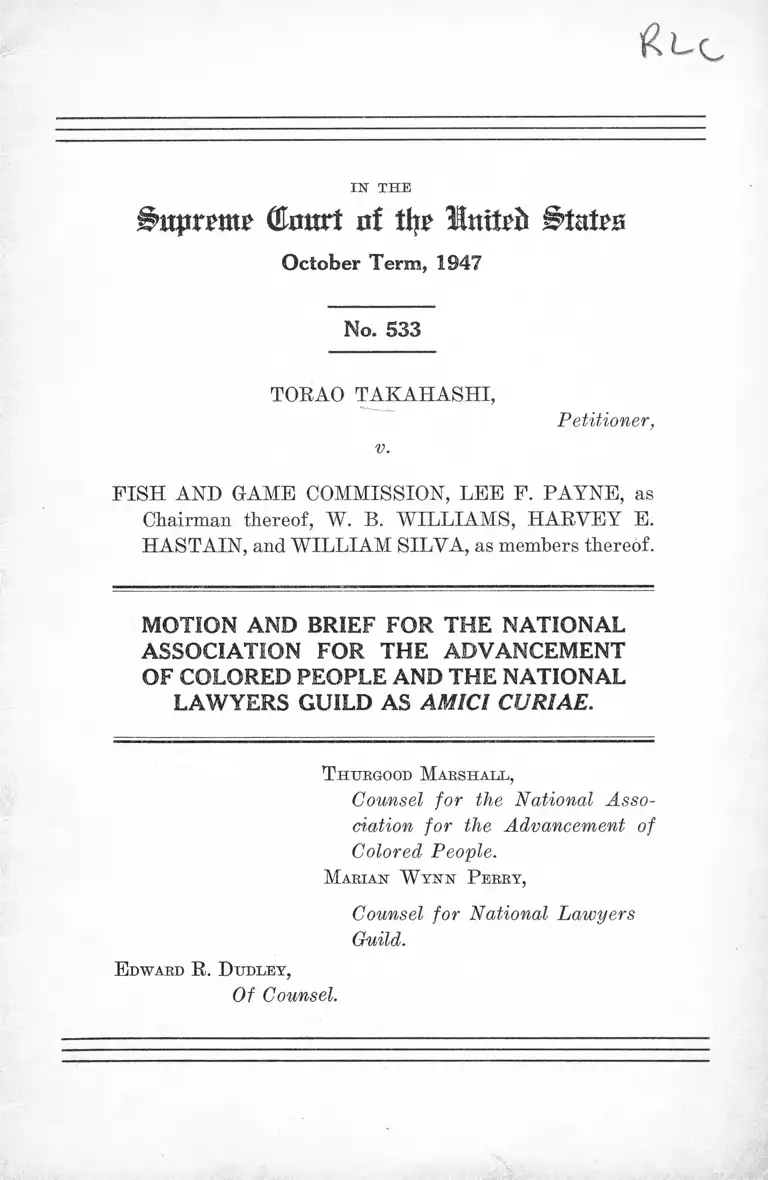

IN THE

dttprme ©Hurt of the Ittitefc States

October Term, 1947

No. 533

TORAO TAKAHASHI,

v.

Petitioner,

FISH AND GAME COMMISSION, LEE F. PAYNE, as

Chairman thereof, W. B. WILLIAMS, HARVEY E.

HASTAIN, and WILLIAM SILVA, as members thereof.

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE AND THE NATIONAL

LAWYERS GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

T hurgood M arshall,

Counsel for the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of

Colored People.

M arian W v x x P erry,

Counsel for National Lawyers

Guild.

E dward R. D udley,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae______ 1

B rief:

Opinion B elow _____________ .1____________________ 3

Statute Involved _________________________________ 3

Questions Presented_____________________________ 4

Statement of the C ase___________________________ 4

Summary of Argument __________________________ 5

Argument :

I Since there is no rational basis for the discrim

ination embodied in the statute, it comes into

fatal conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment 6

II State legislation excluding aliens from the right

to work is an interference with the national

sovereignty __________________________________ 9

A. The legislation here presented is an attempt

to exclude a class of aliens from residing in

the state__________________________________ 9

B. The right to exclude aliens is vested solely in

the Federal Government__________________ 11

III A state law denying to a racial group the right

to engage in a common occupation violates the

obligations of the United States under the

United Nations Charter______________________ 14

Conclusion_____________________________________ — - — 18

PAGE

11

Table of Cases

AUgeyer v. Louisiana, 165 U. S. 578----------- ---—--------- 15

Baldwin v. G. A. F. Seelig, 294 U. S. 511-------------------- 13

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IJ. S. 60— ---------------- --------- 7

Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U. S. 581--- ---------------------- 11

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160-------------------- --- 13

Estate of Tetsubumi, 188 Cal. 645--------------------------- -~ 10

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337--------- 7

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536---------------------------------- 7

Oyama v. California, 16 Law Week, 4108------------------10,17

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U. S. 36-------------------------- 11

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192— —̂ 15

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33-----------------------------9,10,12,15

U. S. v. Curtiss Wright, 299 U. S. 304------------------------- 10

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IJ. S. 356------------------------------ 6

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 IJ. S. 500--------------------- 7

PAGE!

I l l

Authorities Cited.

Aylsworth, “ The Passing of Alien Suffrage” , Am. Pol.

Sci. Rev. X X V (1931) 114 _______________________ 11

Corwin, The Constitution and World Government------- 11

Pinal Report, FEPC, June 28, 1946 --------------------------- 16

Hyde, International Law (2d ed.) _____________ _____ 11

Iehihashi, “ Japanese in the United States” __________ 16

Konvitz, The Alien and the Asiatic in American Law___ 11

McGovney, “ Anti-Japanese Land Laws” , 35 Cal. Law

Rev. 7, 5 1 ________________________________________ 10

State Dept. Publications 2274, European Series, “ Mak

ing the Peace Treaties” ______ ._______________1— 15

4 State Dept. Bulletin 347-451 ______________________ 15

16 State Dept. Bulletin 1077, 1080, 1082______________ 15

United Nations Charter, Articles 55 and 56__________ 14

United States Census, 1940, “ Characteristics of the

Non-White Population” _________________________ 6,14

World Peace Foundation, Documents on Foreign Policy,

Vol. I, 1938-39 ___________________________________ 15

PAGE

ITT THE

i>ttprnttr (tort 0! % Itutrfc Itorn

October Term, 1947

No. 533

T orao T ak ah ash i,

Petitioner,

v.

F ish and G am e C omm ission , L ee F .

P ayne , as Chairman thereof, W. B.

W illiam s , H arvey E. H astain , and

W illiam S ilva, as members thereof.

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE AND THE NATIONAL

LAWYERS GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE.

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for and on behalf of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, and the National Lawyers Guild, respectfully move

that this Honorable Court grant them leave to file the ac

company brief as amici curiae.

2

The issue at stake in the above entitled cause is the

power of a state to discriminate on racial grounds among

persons within its jurisdiction in their exercise of the right

to earn a living in a common occupation. The determina

tion of this issue involves an interpretation of the Four

teenth Amendment which will have widespead effect upon

the welfare of all minority groups in the United States.

Consent of the parties for the filing of this brief has

been obtained for the National Lawyers Guild and has been

requested for the NAACP and will be filed as soon as re

ceived.

T hubgood M arshall ,

Counsel for the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of

Colored People.

M arian W y n n P erry,

Counsel for National Lawyers

Guild.

E dward R . D udley,

Of Counsel.

IN THE

Bnpvmxt CEmtrt of tho Intteft States

October Term, 1947

No. 533

T oeao T a k a h a sh i,

Petitioner,

v.

F ish and Gam e Comm ission , L ee F .

P ayne , as Chairman thereof, W. B.

W illiam s , H arvey E. H astain , and

W illiam S ilva , as members thereof.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AND

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

Opinion Below.

Statute Involved.

The opinion below and the statute involved are set forth

in full in the record and in the Petition for Certiorari filed

herein.

3

4

Questions Presented,

1. Whether a statute of the State of California

denying to aliens ineligible to citizenship the right to

earn their living by commercial fishing is consistent

with the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether such statute is an interference with

the supremacy of the Federal government in the field

of international law and in conflict with treaty obliga

tions of the United States.

Statement of the Case.

The petitioner herein is a citizen of Japan who, under

the naturalization laws of the Federal government, is

presently ineligible to citizenship. He has resided in Los

Angeles, California, continuously since 1907 with the ex

ception of that period of time when he was excluded from

California under the Military Exclusion laws adopted dur

ing World War II. From 1915 until the Military Exclusion

laws petitioner earned his living by commercial fishing on

the high seas off California, which activity was carried on

pursuant to a license granted by the Fish and Game Com

mission of the State of California (B. 1-6).

In 1945, just prior to the restoration of freedom of

movement to Japanese aliens who had been excluded from

California, the state legislature amended Section 990 of

the Fish and Game Code (California Stats. 1945, Ch. 181)

to prohibit the issuance of a commercial fishing license to

persons ineligible to citizenship or to corporations the

majority of whose stockholders, or any of whose officers,

were ineligible to citizenship. Upon the face of the stat

ute, no other criterion is applied for the issuance of such

licenses.

5

Upon petitioner’s return to California in October, 1945,

he found himself, in the last years of his life, excluded

from employment as a commercial fisherman after almost

thirty years of gainful employment in that field.

The court of original jurisdiction, the Superior Court

of the State of California, in and for the County of Los

Angeles, found that this statutory restriction was unconsti

tutional and granted a writ of mandamus (R. 7). On ap

peal to the Supreme Court of California, the judgment of

the lower court was reversed and the constitutionality of

the statute was upheld (R. 30-45). Three judges dissented

from this holding. The decision of the Supreme Court of

California is now before this Court on writ of certiorari.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

I.

Since there is no rational basis for the discrimina

tion embodied in the statute, it comes into fatal conflict

with the Fourteenth Amendment.

II.

State legislation excluding aliens from the right to

work is an interference with the national sovereignty.

A. The legislation here presented is an attempt to

exclude a class of aliens from residing in the state.

B. The right to exclude aliens is vested solely in the

Federal Government.

III.

A state law denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates the obliga

tions of the United States under the United Nations

Charter.

6

A R G U M E N T .

I.

Since there is no rational basis for the discrimina

tion embodied in the statute, it comes into fatal conflict

with the Fourteenth Amendment.

That this legislation is directed at Japanese aliens is

conclusively proven by the 1940 Census figures which show

33,569 Japanese ineligible to citizenship residing in Cali

fornia and fewer than 900 others in the entire continental

United States.

Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment this

Court has been vigilant in assuring that legislative classi

fication of persons resulting in discrimination should bear

a reasonable relationship to the achievement of legitimate

ends of government. In a long line of decisions legislation

has been declared unconstitutional were classification has

been based on race alone.

Considering an ordinance fair on its face, hut in practice

discriminatory against the Chinese, this Court said of the

discrimination:

“ No reason for it is shown and the conclusion

cannot be resisted that no reason for it exists except

hostility to the race and nationality to which peti

tioners belong, and which in the eye of the law is un

justified. ’ ’ 1

Of similar classification Mr. Justice H olmes speaking

for this Court said:

“ States may do a great deal of classifying that

it is difficult to believe rational but there are limits,

1 Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374.

7

and it is . . . clear . . . that color cannot be made the

basis of statutory classification. ’ ’ 2

The' Supreme Court of California justified this legisla

tion as based upon “ the broad powers resting in the state

in regard to the regulation of its fish and game” (R. 38).

In the exercise of that power the court said:

“ Obviously if the legislature determines that

some reduction in the number of persons eligible to

hunt and fish is desirable, it is logical and fair that

aliens ineligible to citizenship shall be the first group

to be denied the privilege of doing so” (R. 38).

Even assuming, arguendo, as the petitioners do not con

cede, that these fish are the “ property” of the state, the

issue remains whether the state may condition the grant

ing of licenses solely upon the race of the applicant, with

out establishing any relationship between the object to be

attained, presumably conservation, and the proscribed

group.

The criticism of this theory put forth as fair and logical

which was made by the dissenting opinion completely ex

poses its lack of logic:

“ I can see no logic in depriving resident aliens,

even though they are not eligible to citizenship, of

the means of making a livelihood, including the pur

suit of commercial fishing. They are lawfully in

habitants and residents of the state. Even if it be

assumed that non residents, both alien and citizens

of the United States, may be excluded from game

and fish on the theory that such resources belong to

the people of the state, the fact remains that resident

aliens are a part of the people—the inhabitants and

2 Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541; See also Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337; Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500.

8

residents of this state. Because some believe that

aliens should be punished by such a penalty is no

basis for a reasonable classification. There is no

sound basis for the argument that because the fish

and game belong to the people of the state, the tak

ing of them may be prohibited to all, and that with

such a broad power any group of people may be ar

bitrarily excluded from the right to take any por

tion thereof. On the basis of that reasoning the

Legislature could validly prohibit persons ineligible

to citizenship from using the highways. They be

long to the state and the traffic hazards would be less

if fewer people were using them. The same is true

of the use of the parks, schools and other public

buildings and places. It could be argued that they

are over-crowded and the more people using them

the greater the cost to the public, all to the diminish-

ment of the resources of the state natural or other

wise. While the state may withhold a privilege if

it elects not to grant it, it cannot arbitrarily prevent

any member of the public from exercising it while

granting such privilege to others. To conclude

otherwise would deprive the equal protection prin

ciple of all meaning” (R. 49).

The complete lack of reasonableness of the legislation

becomes apparent when one looks to the end which is sup

posed to be accomplished. There is no limit fixed on the

number of licenses which may be issued, nor does the state

limit the number of fish to be taken or the period during

which fish may be taken. No limits of the size of nets or

the equipment used in commercial fishing are established.

The licenses are not limited to residents of the state, but

persons from throughout the entire country may flock to

California, to get licenses and fish without restriction in the

coastal waters. For every 100 aliens ineligible to citizen

ship who are denied commercial fishing licenses, 500 new

licensees may come in from every other state or country,

9

urged on by the thought of a profitable field of endeavor

from which skilled workers are now barred by statute. No

conservation is achieved.

There being no reasonable relation between the objec

tives claimed as justification for this statute and the means

sought to achieve it, no doubt can be entertained that this

legislation like the statute in Truax v. Raich8 is discrimina

tion against a group of unpopular aliens, as such, in compe

tition with citizens. As such it comes into fatal conflict

with the Fourteenth Amendment and must fail.

II.

State legislation excluding aliens from the right to

work is an interference with the national sovereignty.

The present complicated state of international relations

demonstrates the wisdom of the concept that all power in

the field of international law, which includes within its

scope immigration as well as the power to confer citizen

ship, must rest wholly in the Federal government. The

legislation presented to this Court is an unwarranted and

dangerous interference with that power.

A. The legislation here presented is an attempt to

exclude a class of aliens from residing in the state.

The amendment to the Fish and Game Code prohibiting

aliens ineligible to citizenship from engaging- in the com

mon occupation of commercial fishing was enacted in 1945

in the midst of an anti-Japanese hysteria on the west coast

which exhibited itself in acts of violence which were ex

tended even to honorably discharged veterans who had

fought in the American army against the Japanese govern- 3

3 239 U. S. 33.

1 0

ment. While on its face this statute makes no mention of

race, the dissenting opinion in the court below, viewing the

historical background of this legislation and of court de

cisions on anti-alien legislation in California, found that

the law in the instant case is aimed solely at the Japanese

(R. 53). See also D. 0. McGovney, “ Anti-Japanese Land

Laws” , 35 Cal. Law Review 7, 51. The concurring opin

ions of Mr. Justice M u r p h y and Mr. Justice B rack in

Oyama v. California* rest in large part upon the fact that

legislation against land ownership by aliens ineligible to

citizenship in our western states has been “ designed to

effectuate a purely racial discrimination” . . . “ is rooted

deeply in racial, economic, and social antagonism” . . .

and is the result of “ racial hatred and intolerance.” Like

the Alien Land Law, the California law here under review

is designed to “ discourage the coming of Japanese into

this State.” 4 5 6

That the power to exclude aliens from the right to earn

their living was also the power to exclude them from en

trance and abode was recognized by this Court in Truax

v. Raich, where it was stated:

“ The assertion of an authority to deny to aliens

the opportunity of earning a livelihood when law

fully admitted to the state would be tantamount to

the assertion of the right to deny them entrance and

abode, for in ordinary cases they cannot live where

they cannot work. . . . ” e

When this fundamental purpose of the law is recognized,

it becomes clear that the statute is an interference with the

sovereignty of the Federal government in the field of immi

gration, naturalization, and international law.

4 16 Law Week 4108,-------U. S . --------.

5 Estate of Tetsubumi Yano, 188 Cal. 645.

6 239 U. S. 33, 42.

1 1

B. The right to exclude aliens is vested solely in the

Federal Government.

The Chinese Exclusion Case7 established and United-

States v. Curtiss W right8 reaffirmed that the investment

of the Federal government with the powers of “ external

sovereignty” in the field of international affairs was “ a

necessary concomitant of nationality.” Indeed, in “ The

Constitution and World Organization” , Professor Corwin

has concluded from these cases that in the field of inter

national relations the Federal government does not operate

under constitutional restraints.9 As late as 1945, the law

of nations was not viewed as placing any restriction upon

the discriminations which a sovereign might practice in

establishing tests of undesirability for aliens seeking ad

mission.10 Thus, the Federal government, and it alone,

can admit or exclude aliens, without restriction or limita

tion under the law today.

Despite the confused state of the law as to citizenship

prior to the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment,11 today

the power to grant or withhold citizenship in our nation is

also vested in the Federal government. However, the states

continued to vest aliens within their respective boundaries

with certain privileges of state citizenship, and it has been

said that it was not until 1928 that an election was held in

which no alien voted.12 Their power to do so is not chal

lenged.

7 130 U. S. 581.

8 299 U. S. 304.

9 Pp. 6, 19, 29-30. See also M. R. Konvitz, The Alien and the

Asiatic in American Law, Chapter 1.

10 C. C. Hyde, International Law (2d Ed.) I, 217.

11 See the opinion of this Court in Slaughter House Cases, 83 U. S.

36, where it is stated, at page 73, that prior to 1866: “ It had been

said by eminent judges that no man was a citizen of the United States

except as he was a citizen of one of the states composing the Union.”

12 Aylsworth, “ The Passing of Alien Suffrage” , Am. Pol. Sci. Rev.

X X V (1931) 114.

1 2

But a far different problem is presented when, after the

admission of an alien by the Federal government, the state

seeks, as here, to place additional and unreasonable burdens

upon him. Though the Federal government may be un

restrained by constitutional protections of private rights in

determining whether to admit or exclude an alien, once

admitted, even though denied national citizenship by Con

gressional action, the alien is a person clothed with those

constitutional guarantees of life, liberty and property and

the protection of equal laws which form the basis of a de

mocracy. The states inherit no such unrestricted power in

relation to a resident alien as is possessed by the Federal

government in regard to an alien seeking entry.

But another and equally serious restriction on the power

of states to harry, persecute and, if possible, drive from

their border aliens legally admitted to the country, arises

from the fact that though we are a federation of sovereign

states, the component parts may not isolate themselves and

restrict the freedom of persons to establish residence or

travel freely in the states.

Such was the reasoning which led this Court to hold

unconstitutional an Arizona law restricting the right of

aliens to work in common occupations, thereby excluding;

them from residence. In Truax v. Raich, this Court found

that the attempt to exclude aliens from residence in certain

states by state action would be derogatory of the power of

Congress under which those aliens had been lawfully ad

mitted to the country. In that decision, this Court spoke

of the right of aliens, without the interference of the states,

to enjoy “ in their full scope the privileges conferred by

admission.”

13

In the words o f Mr. Justice Cardoza, our Constitution

was “ formed upon the theory that the peoples of the several

states must sink or swim together and that in the long run

prosperity and salvation are in union and not division.” 13

Attempts by the states to isolate themselves from the

economic disasters of other sections of the country by limit

ing the right of citizens to travel freely within the country

have been struck down by this Court as subversive of the

welfare of the nation on much the same basis, though re

liance was placed on the commerce clause in so doing.14

Political and ecomonic reality in a world of shrinking

dimensions give added emphasis to the legal requirement

that the states of our nation must form a unit for the pur

pose of determining the right to live within the states, which

is, of course, contingent upon the right to earn a living

within the states.

The ultimate result of laws such as that here challenged,

if valid, would be to vest in the Federal government the

right to make only an empty legal determination of the right

of an alien to enter the United States while granting to the

forty-eight states the power, by forty-eight individual laws,

to exclude such persons from the United States. Viewed in

that light, the interference with an inherent and necessary

power of Federal sovereignty is clear and for that reason

alone, this law is invalid.

13 Baldwin v. G. A . F. Seelig, 294 U. S. 511, 523.

14 Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.

14

III.

A state law denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates the obliga

tions of the United States under the United Nations

Charter.

While the statute on its face purports to have a certain

impartiality by describing the proscribed group as “ persons

ineligible to citizenship, ’ ’ the 1940 Census Eeport18 19 shows

only 48,158 aliens ineligible to citizenship in the country,

of which 33,569 were Japanese aliens residing in California.

By the same census only 853 aliens ineligible to citizenship,

other than Japanese, resided in the entire United States.

These figures conclusively establish that the legislation be

fore this Court is aimed at one racial or national group

and one alone—the Japanese.

Whatever the protections furnished in the Federal Con

stitution against state legislation unreasonably discriminat

ing on racial or natonal grounds, it is clear today that the

Federal government has pledged itself, with the other mem

bers of the United Nations, to fulfill in good faith an obliga

tion to promote “ universal respect for and observance of

human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without

distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” 16

The United Nations Charter, as a treaty duly executed

by the President and ratified by the Senate 17 is declared

to be the supreme law of the land by Article VI, Section 2

of the Constitution and any laws of any state to the con

trary must fall before this non-discriminatory provision

of a treaty obligation.

18 U. S. Census, 1940, “ Characteristics o f the Non-White Popula

tion,” p. 2.

19 United Nations Charter, Articles 55 and 56.

17 51 Stat. 1031.

15

There can be no doubt that the right to work is one of

the fundamental freedoms to which the United Nations

Charter refers. It has been so declared by numerous de

cisions of this Court. As was stated by this Court in

Truax v. Raich, supra,

“ It requires no argument to show that the right

to work for a living in the common occupations of

the community is the very essence of the personal

freedom and opportunity that it was the purpose

of the (14th) Amendment to secure.”

This principle has been reiterated under many different

circumstances, and the right to work has been protected

against action only indirectly that of the government.18

While the interest of nations in foreign affairs was

originally confined to the treatment of their own nation

als in other countries, the scope of international negoti

ations has been constantly broadening. At the close of the

First World War treaties signed between many nations

provided for the protection of civil rights of national

minorities in no way related to the parties signatory. More

recently our government included such provisions in

treaties of peace with Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary and Eou-

mania.19 That Japan is not yet a member of the United

18 See Allgeyer v. State of Louisiana, 165 U. S. 589; Steele v. Loui

siana & Nashville R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192.

19 “ Making the Peace Treaties,” Dept, of State Publications, 2274,

European Series; 16 State Dept. Bulletin 1077, 1080, 1082. See also

Resolution No. 51 of the International American Conference on Prob

lems of W ar and Peace, Mexico City, 1945; Department of State

Bulletin No. 4, March 18, 1945, pp. 347-451. See also the Resolution

adopted by the Eighth International Conference of American States

at Lima, Peru, in 1938, reading in part as follows: “ That the demo

cratic conceptions of the state guarantees to all individuals the condi

tions essential for carrying on their legitimate activities with self-

respect.” Document on Foreign Policy, Vol. I, 1938-1939, World

Peace Foundation, p. 49.

16

Nations in no way diminishes the obligation of this country

to treat Japanese aliens resident here fairly and in a non-

discriminatory manner. Our failure to do so has serious

implications for world peace.

The passage of such laws as have existed in this coun

try discriminating against the Japanese, including the

congressional action depriving them of the possibility of

becoming American citizens and their exclusion under the

Quota Act, does not pass unnoticed in other nations. Even

in 1924 when means of communication were much less de

veloped, word of the Japanese Exclusion Act caused anti-

American demonstrations and denunciations of our coun

try in Japan.20 Today the Japanese press and the press

of all nations follow more closely than in 1924 the practices

with which we implement our protestations of democratic

principles. As was stated by Mr. Dean Acheson on May

8, 1946, when he was Acting Secretary of State: 21

“ the existence of discrimination against minority

groups in this country has an adverse effect upon

our relations with other countries. We are reminded

over and over by some foreign newspapers and

spokesmen, that our treatment of various minorities

leaves much to be desired. While sometimes these

pronouncements are exaggerated and unjustified,

they all too frequently point with accuracy to some

form of discrimination because of race, creed, color,

or national origin. Frequently we find it next to im

possible to formulate a satisfactory answer to our

critics in other countries; the gap between the things

we stand for in principle and the facts of a particular

situation may be too wide to be bridged. An atmos

phere of suspicion and resentment in a country over

20 Y. Ichihashi, Japanese in the United States (Stanford University

1932, p. 315).

21 Final Report, FEPC, June 28, 1946, p. 6.

17

the way a minority is being treated in the United

States is a formidable obstacle to the development

of mutual understanding and trust between the two

countries. We will have better international relations

when these reasons for suspicion and resentment

have been removed.”

As stated b y Mr. Justice B lack in his concurring opinion

in Oyama v. California, supra:

“ How can this nation be faithful to this inter

national pledge if state laws which bar land owner

ship and occupancy by aliens on account of race are

permitted to be enforced!”

Within the framework of a federal form of government

there may be many fields in which the United Nations Char

ter will require specific enabling legislation before it be

comes an effective obligation upon the people of the United

States. Yet certain aspects of the Charter are by force of

American law sufficiently clear to constitute the supreme

law of the land as a self-executing obligation and thus to

supersede state laws which violate them.

That the law here presented for review must fall before

the supremacy of a treaty obligation of the United States

was recognized by the concurring opinion in the Oyama ease.

Indeed, Mr. Justice M u r p h y said of the Alien Land Law

that it

“ does violence to the high ideals of the Constitution

of the United States and the Charter of the United

Nations . . . Human liberty is in too great a peril

today to warrant ignoring that principle in this case.

For that reason I believe that the penalty of un

constitutionality should be imposed upon the Alien

Land Law.”

1 8

Conclusion.

I f at other times in our history there were moral grounds

for the protection of unpopular minorities, there are today

compelling practical reasons for the revitalizing of the

practices of democracy within our borders. The statute

here challenged not only vitiates constitutional guarantees

of personal freedom, but weakens our nation in a field in

which the Federal government is supreme. For these rea

sons it is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

Supreme Court of California be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

T hubgood Ma r sh a ll ,

Counsel for the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of

Colored People.

M arian W y n n P erry,

Counsel for National Lawyers

Guild.

E dward R. D udley,

Of Counsel.

[6558]12

L awyers Press, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y . C. 7 ; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300