Harrison v. Dole Brief for Federal Cross/Appellees Reply Brief for Federal Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 18, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. Dole Brief for Federal Cross/Appellees Reply Brief for Federal Appellants, 1983. ecc5658f-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/928f824c-a940-48cb-bfb8-9b9f21375323/harrison-v-dole-brief-for-federal-crossappellees-reply-brief-for-federal-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

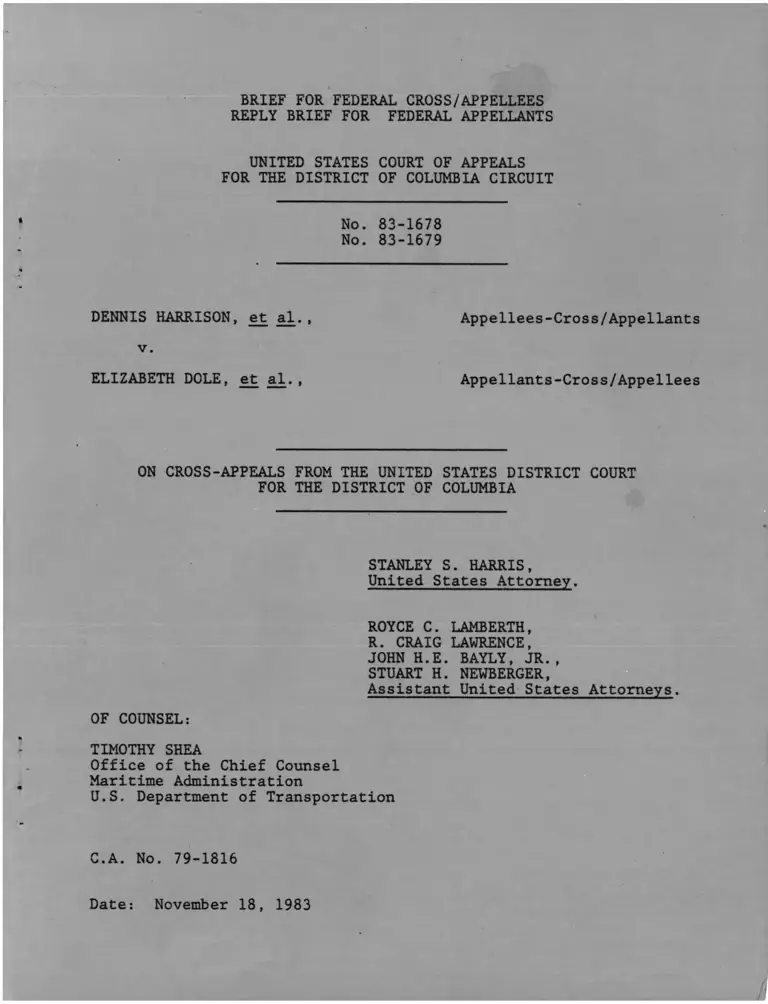

BRIEF FOR FEDERAL CROSS/APPELLEES

REPLY BRIEF FOR FEDERAL APPELLANTS

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No.

No.

83-1678

83-1679

DENNIS HARRISON, et al. , Appellees-Cross/Appellants

V.

ELIZABETH DOLE, et al. , Appellants-Cross/Appellees

ON CROSS-APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

STANLEY S. HARRIS,

United States Attorney.

ROYCE C. LAMBERTH,

R. CRAIG LAWRENCE,

JOHN H.E. BAYLY, JR.,

STUART H. NEWBERGER,

Assistant United States Attorneys.

OF COUNSEL:

TIMOTHY SHEA

Office of the Chief Counsel

Maritime Administration

U.S. Department of Transportation

C. A. No. 79-1816

Date: November 18, 1983

I N D E X

Page

INTRODUCTION ........................................... 1

Plaintiff Class' Cross-Appeal .................... 1

MarAd's Appeal .......................... . . . . 2

FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..................................... 3

A. Plaintiff Spencer's Administrative Claim . . . 3

B. The "Destruction of Records" Claim .......... 4

C. Plaintiffs' Competitive Selection Analysis . . 5

D. MarAd's "Unvalidated Selection" System . . . . 5

E. The Anecdotal Evidence ...................... 8

F. MarAd's Statistical Analyses ................ 8

G. Plaintiffs' Statistical Analyses ............ 13

ARGUMENT............................................... 15

I. Plaintiffs' Cross-Appeal ..................... 15

A. The District Court Properly Held That

MarAd Has Not Discriminated Against The

Certified, Compound Class .............. 15

B. The District Court Properly Held That

MarAd Has Not Discriminated Against

Women Employees On the Basis of Sex . . . 17

C. The District Court Properly Refused to

Review Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Statistical

A n a l y s i s ............................... 18

D. The District Court Properly Held That

the Affirmative Action Provisions of

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 Do Not Create A

Private Right Of Action ................ 20

E. The District Court Properly Limited

The Class Relief to the Extent

Challenged by Plaintiffs' .............. -23

II. MarAd's Appeal................................. 26

A. The District Court Erred In Certifying The

Compound, Across-the-Board Class . . . . 26

B. The District Court Erred In Finding

Partial Class (Race) Liability ........... 30

C. The District Court's Relief Order,

Requiring A Validation Study, was

Erroneous . . . .. ....................... 32

CONCLUSION............................................... 34

TABLE OF CASES

Baca v. Butz, 394 F. Supp. 888 (D.N.M. 1975).......... 22

Borrell v. U.S. Intern. Communications Agency.

1T5TT.2d W L (D.C. Cir. 1982)— . . . .......... 20

Brown v. GSA, 425 U.S. 820 (1977) .................... 31

Bush v. Lucas, U.S. , 103 S. Ct.

2104 ( T O T TT". . . T T ~ ........................... 22

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677

OT79) .— r ........................................... 21

Council of the Blind of Del. City Valley v. Regan,

709 F.2d 1521 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (en banc) ............ 20

Court v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66 (1975)........................ 20

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, U.S. ,

S. Ct. , 1T> L. Ed. 2d 628~(T283) .~TT . . . . 23

East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc. v. Rodriguez,

431 U.S. 295 (1978) . ............... . . . . . . 26

*EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 698 F.2d 633

(4th Cir. 1983), cert, granted, sub, nom., Cooper v.

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 52 U.S.L.W. 3342

(October 31, 1983)(No. 83-185).................... 25, 28

^General Telephone Co. of the Southwest v. Falcon,

457 U.S. 148 (1982) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ................ Passim

Lawler v. Alexander, 698 F.2d 439 (11th Cir. 1983) . . . 28

ZJ Cases chiefly relied upon.

Page

-ii-

McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62 (D.C. Cir. 1982) . . . . 31

Mervin v. F.T.C., 591 F.2d 821 (D.C. Cir. 1978) . . . . 25

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d

798 (5th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, U.S. ,

103 S. Ct. 451 (1982)............................... 30

*Pouncy v. Prudential Ins. Co. of America, 668 F.2d

795 (5th Cir. 1982) ................................. 31

Shivers v. Landrieu 674 F.2d 906 (D.C. Cir. 1981) . . . 21

Talev v. Reinhardt, 662 F.2d 888 (D.C. Cir. 1981) . . . 31

Toney v. Block, 705 F.2d 1364 (D.C. Cir. 1983) ........ 29

*Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094 (D.C. Cir. 1983) cert.

pet. pending, 52 U.S.L.W. 3387 (No. 83-706) ........ Passim

*Valentino v. U.S. Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56

(D.C. Cir. 1982)..................................... Passim

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 455 U.S. 385

(1982)............................................... 23

OTHER AUTHORITIES

42 U.S.C. § 2000e—16 ................................... Passim

5 C.F.R. § 713.604 (1977) ............................. 29

5 C.F.R. § 1613.214(a) ................................. 25

5 C.F.R. § 1613.602 ................................. 25

Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 701 et seq. . . 21

Rule 23, F.R. Civ. P.................................... Passim

OPM X-118 Standards ................................... Passim

Page

-iii-

BRIEF FOR FEDERAL CROSS/APPELLEES

REPLY BRIEF FOR FEDERAL APPELLANTS

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 83-1678

No. 83-1679

DENNIS HARRISON, et al. , Appellees-Cross/Appellants

v.

ELIZABETH DOLE, et al., Appellants-Cross/Appellees

ON CROSS-APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

INTRODUCTION

Federal cross-appellees (federal appellants) — ̂ hereby

respond to the issues raised on the cross-appeal and, in addition,

reply to appellees' (cross-appellants) — brief filed in the

present case.

The Plaintiff Class' Cross-Appeal

In the pending cross-appeal, plaintiffs below challenge

several adverse holdings of the District Court. More particularly,

T7 As with their opening brief, federal cross-appellees will

refer to themselves as "MarAd."

2/ "Plaintiffs" or "Class members".

the issues on cross-appeal include: (1) whether the District

Court properly found that MarAd had not discriminated in its

employment practices on the basis of sex or race either against

(a) a compound, across-the-board class of all non-white males, or

(b) that portion of the compound class consisting of women; (2)

whether the District Court properly refused to consider a statisti

cal report prepared by plaintiffs' experts after the trial on the

merits had been completed; (3) whether the District Court properly

held that the affirmative action provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16

do not provide federal employees with an independent, private

cause of action against the employing agency; and (4) whether the

District Court properly denied certain class relief. As dis

cussed below, the District Court correctly ruled on all the

issues raised in the cross-appeal and its judgment should be

affirmed to that extent.

MarAd's Appeal

As noted in MarAd's opening brief, the District Court

incorrectly ruled on several critical issues. These issues

include: (1) the District Court's error in certifying an across-

the-board, compound class in contravention of the strict require

ments of Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the

Supreme Court's ruling in General Telephone Co. of the Southwest

v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 148 (1982) (Falcon); (2) the District Court's

error in bifurcating the compound class,after trial, notwith

standing its finding on the merits that MarAd had not discrimi

nated against the certified, compound class; (3) the District

Court's error in ordering agency-wide validation of MarAd.'s

2

promotion criteria (a) where plaintiffs had concededly failed to

prove intentional, disparate treatment of black employees in

promotions, and (b) where MarAd (like all federal agencies) was

required to follow the promotion criteria set down by the Office

of Personnel Management, (a non-party) in the OPM X-118 Standards;

and (4) the District Court's overbroad inclusion of black class

members in its order providing individual class member relief.

To that extent, the District Court's findings should be reversed

and remanded.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

These cross-appeals arise out of District Judge Louis B.

Oberdorfer's findings in a Title VII class action wherein all

black and women applicants and employees of the Maritime Admini

stration challenged that agency's employment practices and

policies. After certifying an "across-the-board" class, conducting

extensive pretrial proceedings, and holding a two-week trial, the

District Court found that MarAd had not engaged in discriminatory

practices against women but had against blacks. Thereafter,

various types of relief issued. MarAd's opening brief extensively

discussed the factual background of the present appeals, (Brief

pp. 9-42). Consequently, MarAds responds to plaintiffs' brief's

numerous factual statements only as they require a response.

A. Plaintiff Spencer's Administrative Claim

Plaintiffs' assertion that Ms. Spencer was promoted after

the class claim was filed apparently suggests that it was only

because of the claim that she was promoted. On the contrary,

3

when Ms. Spencer (and other employees) complained about a posi

tion selection in March 1977 MarAd agreed, in writing, to re

advertise the position and designate a new selecting official.

This position was readvertised on April 13, 1977 and closed in

May 1977. Thus, Ms. Spencer's selection in August 1977 was the

result of the April 1977 compromise wherein the position was

readvertised. (DX 98, 110, and 132 Is 357-364). Because this

position was not filled until Ms. Spencer was selected, she could

not have any individual backpay claim relating to the present case.

In response to Ms. Spencer's "separate claim" regarding

failure to re-classify her position in early 1977, MarAd recom

mended that she be promoted by reclassification but, under

established agency rules, had to refer the recommendation to the

Department of Commerce. The Department denied the request

shortly before Ms. Spencer was selected for the readvertised

position in August 1977. DX 130, Is 152-154.

B. The "Destruction of Records" Claim

Plaintiffs suggest that MarAd was engaged in a careless and

broad effort to dispose of relevant employee records. However,

the only relevant records that were unavailable were the SF-171

application forms which MarAd continued to return to rejected

applicants. This practice had little or no impact on the reliabi

lity of either party's statistical analysis. —

Plaintiffs' claim on this "issue" is, therefore, unsupported

by the record.

J7 Plaintiffs speculate that, if only they had available more

information on the race of applicants, the results of their

(FOOTNOTE CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE)

4

C. Plaintiffs' Competitive Selection

Analysis_______________

Plaintiffs' treatment of competitive selections confuses the

process. Their analysis describes MarAd's decisions on assignment

of job series as involving substantial employer discretion and

judgment. However, assigning the job series is the process of

associating, i.e.; an accountant position with the appropriate

federal job series, i.e. , series 510. Although there was

evidence bearing on the degree of discretion involved in applying

the OPM X-118 standards (see DX-129; 197 and 193; Op. at 7, 8 and

35) (JA 204, 205 and 235), there was no testimony suggesting that

the assignment of the series involved any substantial discretion.

To the contrary, there was substantial evidence that these

decisions are subject to detailed, government-wide guidance from

OPM. See DX-130; Is 95-105.

3/ (FOOTNONTE CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE)

statistical analyses might change to their advantage. (Plain

tiffs' Brief p. 16) Yet, there was no testimony that the avail

able data was insufficient to permit reliable conclusions.

MarAd's expert, Dr. Michelson, specifically undertook analyses to

measure the sensitivity of the data and fairly adopted conserva

tive methodologies. (DX 120). Plaintiffs seek to blame MarAd's

temporary continuance of its practice of returning Form SF 171's

to applicants for this information loss. However, plaintiffs

make no attempt to quantify the significance of the lost infor

mation. Of course this would be quite a task, given that the SF

171 Forms do not list race identification. Because all of the

returned SF-171's would be from non-MarAd applicants, race

information would have been obtainable from the only other

available source, OPM (DX 120 p. 10 and 18) . However, cross

checking applicants of unknown race with OPM records yielded

racial identification for only a small fraction of applicants. Id.

5

In addition, plaintiffs assert that the number of candidates

who may be referred to a selecting official is nearly unlimited.

However, this is clearly not the case. Certificates usually

include three to five candidates, with ten the maximum number

that may be referred when meaningful distinctions cannot be made.

(See DX 104, MAO 730-335 section 10 (1979); MAO 730-733 section

11 (1969)). A larger number of candidates may be referred when

multiple selections are made from the same certificate. (See,

e.g., PX 180) .

D. MarAd1s "Unvalidated" Selection System

Plaintiffs' suggest that MarAd somehow was required to

undertake a validation of its selection system prior to trial.

This claim is utterly without support. Up until January 1980,

collection of adverse impact data from applicants was prohibited

by 0PM. Once the prohibition was removed, MarAd (along with the

Department of Commerce), proceeded to develop a data collection

and storage system. This system was developed and put into

operation by late 1980. (DX-129, 2s 231-233).

In the same vein, MarAd offered extensive testimony about

the job relatedness of its selection systems and its conformity

with 0PM requirements. This evidence showed that, at the initial

stage, the basic (or "minimum") qualifications were taken from

the OPM X-118 and, since 1977, MarAd had added basic qualifica

tions beyond the X-118 on only one occasion. (DX 129, 2 193).

At the next stages, (rating and ranking), the primary criteria

were always training, education and prior experience. Prior to

1979, awards and appraisals were given some consideration but

6

afterwards, not at all. DX-129 5s 198-200. These criteria are

job related by definition. Because the data collection system

was the first step in any formal evaluation, that process had not

advanced to a validation by the time of trial (early 1982).

In order to bolster their unsupported suspicion that the

MarAd personnel system was subject to supervisory manipulation,

plaintiffs exaggerate the number and significance of positions

they describe as "unique" (Brief p. 12) The District Court,

however, did not find that there were a substantial number of

positions at MarAd that were unique to it but found, instead,

that there were "a number of unique or one of a kind jobs." (Op.

7) (JA 204) Neither plaintiffs' nor the Court ever identify

these positions. MarAd identified them as those classified as

examiners in the 301 job series (DX 130 1 139) . Inspection of

PX-1 indicates that this is not a substantial number of positions.

Plaintiffs then confuse the differing nature of the two sets

of standards that are applied to these "unique" positions.

Classification standards for these jobs are constructed by a

cross-comparison of closely related functions. (DX 130, 5 141).

On the other hand, qualification standards for the 301 series

have requirements that call for general and specialized experi

ence. (DX 129, 5 192).

Contrary to plaintiffs' assertion (p. 12), MarAd has never

contended that career-ladder positions must be "professional".

However, at the GS levels upon which plaintiffs' statistical

analysis focused (GS 7-15) , all career-ladder positions were

7

professional. The District Court found that "[wjhile nonpro

fessional jobs at MarAd could possibly be designated career

ladder, there is no evidence that failure to do so is in any way

discriminatory." (Op. 29 and 30) (JA 229-230).

Finally, defendants note that plaintiffs' claim of inade

quate training (p. 14) fails to recognize that OPM requires

training to be job related. DX-131, fs 276-278. -

E. The Anecdotal Evidence

Plaintiffs' discussion of the anecdotal evidence overstates

the record. (pp. 14-15). The only testimony offered by plaintiffs

relating to individual discrimination was proffered by nine class

5 /members (other than the three named plaintiffs). —

4/ Plaintiffs devote undue attention to awards data with little

explanation for its prominence. They assert that MarAd's awards

data indicates a significant disproportion in favor of white

males. This is in error. In all cash awards, no significant

disproportion was observed. (DX-120, Appendix D). MarAd admitted

that a disproportion of honorary awards (bronze medals) went to

white males but explained that such awards carried no consequences

in compensation. Because honorary awards are made only for

significant contributions to agency programs over a long period

of time, the type of position held bears on the award distribu

tion. (DX-104, MAO 740-451, section b). Plaintiffs seek to

argue that their awards totals should be adopted. Defendants

objected to receipt of plaintiffs' awards totals because it was

unsponsored by a competent witness. Conversely, MarAd's awards

totals, sponsored by Maxine Anderson (the personnel specialist

who maintained the data), is more reliable and must be accepted.

See Tr. 664-676.

5/ These witnesses were John Blackburn; Gerald Brown; Mary

Duckett; Joan Forman; Vontell Frost; Sharon Howard; Freddie

Johnson; Rona LaPrade & James White. Ms. Forman and Ms. Frost

did not testify — facts relating to their claims were admitted

by MarAd. Plaintiffs had offered testimony from Mary Arter,

Jessie Fernanders and Joyce Campbell but these persons did not

assert that they were victims of discrimination. See Tr. 267-

404, 480-543. See also Plaintiffs' Substituted Pre-Trial Brief,

pp. 6, 9, 12, 72, 76 and 116-118. (R 151).

8

For its part, MarAd vigorously opposed each of these asser

tions of discrimination. —^

F. MarAd1s Statistical Analyses

MarAd offered two statistical studies that were recognized

by the District Court to be "more reliable" than plaintiffs'.

(Op. 28) (JA 228). One of its studies was a survival analysis of

non-competitive promotions that separately compared time-in-grade

(tenure) by race, sex and white males against others for career

ladder and non-career ladder jobs. In addition, a strict joint

test was undertaken that sought to combine all the positions

while preserving the differences. (DX-119).

For competitive selections MarAd's expert, Dr. Michelson,

offered a multiple pools analysis of over 400 vacancy announce

ments over the period from 1977 to early 1981. (DX-120 p.

17). — The advantage of the multiple pools analysis was that it

correctly identified the rejected applicants for each vacancy as

6/ See Defendants' Post-Trial Brief P. 11-63-75) (R 205); Tr. pp. 631-770, 776-817, 881-894.

l_l While MarAd's expert did recognize that a multiple pools

analysis might not be appropriate for candidates competing

against a standard (as is the case at the qualification stage) ,

this does not compel the concludion that plaintiffs aggregation

of all qualification decisions was appropriate. After all,

applicants were competing against scores of standards. See DX-3.

Plaintiffs, of course, made no attempt to allocate qualification

success rates either by series or job type. In any event, where

applicants are competing against each other at the ranking and

certification stage, the use of the multiple pools analysis is

wholly appropriate. (Op. 22 and 28) (JA 222 and 228)

9

only those who applied for the vacancy. Statistical techniques,

such as plaintiffs, that lump together applicants for different

vacancy announcements result in treating disappointed applicants

from all announcements as "rejects"-- where the racial or sexual

mix of the applicants varies from announcement to announcement,

the difference in the results are substantial. (DX-120 Appendix

B). The multiple pools analysis included breakdowns for clerical,

non-clerical, low-level (GS-12 and below), career-ladder, and

upper-level positions. Dr. Michelson's analysis separately

compared the "success" rates of applicants by race, sex and white

males against others, analyzing: (1) applicants vs. selectees;

(2) qualifieds vs. selectees; (3) certifieds v. selectees.

After all of these permutations, the only area where any results

remotely favorable to plaintiffs emerged was the disproportionate

failure of black clericals to meet minimum qualifications. (DX

120 pp. 60-63).

Moreover, the survival analysis of career ladder promotions

(which are non-competitive) indicated no statistically signifi

cant differences for any race/sex subgroup. The data indicated

that, with only one exception, the differences in median time to

promotion ranged from 12.6 to 13.3 months for grades 7, 9 and 11

regarding any race/sex subgroup. In a white males v. others, the

median times to promotion differed by only .2 months for any

grades. (DX 119 pp. 13-20).

To meet plaintiffs' claim that MarAd unduly disaggregated

the data, Dr. Wyant also performed a joint test where the pro

fessional (e.g., career-ladder) and non-professional tenures were

10

all included and adjusted for their being in different groups.

This analysis treated all positions within the two respective

groups (professional v. non-professional) as equally promotable.

Because of its complexity and its conservative assumptions, this

strict analysis established, in effect, the outer perimeter for

statistical speculation. The results of this analysis showed an

unlikely, but still not statistically significant, .05 level.

(DX. 119 p. 33-36). ^

Dr. Michelson's analysis of the competitive promotions

strongly rebutted plaintiffs' claims. The analysis of the

success rate of applicants by sex for grades GS-13 through 18

showed that the probability of selecting the observed number of

females (or fewer) from among those determined to be eligible — ̂

was .99 -- indicating a statistically significant overselection

of women. For GS-12s and below, Dr. Michelson likewise found

that the probability of selecting the observed number of females

(or fewer) was again .99. Similarly, Dr. Michelson found that

the success rate of eligible females competing for entry into

career ladder positions was .90. (DX-120 pp. 33-37).

17 The probabilities are expressed here in hundredths. Low

probabilities indicate underselection. The .50 figure would

represent the "expected" value. Figures over .50 indicate

overselection. Plaintiffs, who are reduced to arguing that this

analysis "comes within a hair" of showing statistical significance, ignore the severity of the test.

9/ Dr. Michelson testified that the relevant comparison was

between qualified applicants vs. selectees because this compared

applicants who were interested and minimally qualified. See

generally Tr. 896-993. However, he also displayed data comparing

applicants and selectees as well. Id.

11

This data firmly refuted any notion of sex discrimination. The

District Court agreed, noting that

[a]s the analysis of Dr. Michelson shows

women have, if anything, been selected in

disproportionately greater numbers in competi

tive appointments at MarAd. Though some of

this overselection of women disappears if the

apparent bias in favor of applicants from

within MarAd is factored in [footnote omit

ted) , there remains a slight, statistically

insignificant preference for women.

(emphasis in original) Op. 33. (JA 223)

Dr. Michelson's analysis of the success rate of black

eligibles at GS-13 and above arrived at a .31 level, a figure

that is fully consistent with an unbiased selection process. The

success rate of black eligibles at GS-12 and below was determined

to be effectively zero owing entirely to underselection of blacks

in clerical positions. Thus, the probability of selecting the

observed number (or fewer) of black clericals was .01. However,

for blacks competing for career ladder positions the figure was

.57 and for all low level announcements (excluding clericals) it

was .22. Because of the number of clerical selections, its

results predominated the low level announcement results. Dr.

Michelson's review of the clerical selections of blacks indicated

that they were underselected by 12 positions to the benefit of

white females and non-black minorities. (DX-120, pp. 40-55).

Thus, only one isolated, statistically significant outcome was

observed — blacks competing for clerical positions.

Finally, Dr. Michelson also performed three white males

against others analyses which yielded results quite favorable to

MarAd. The first analysis yielded probabilities of .19 for GS-1

12

through 12 and .97 for grades GS 13 through 18 for the success

rates of non-white male eligibles using only applicants whose

race was known. The second analysis assigned race to males of

unknown race in proportion to the race composition of the rejected

applicants. This yielded probabilities of .68 for GS-1 through

12 and .96 for GS-13 and above. (DX-120 pp. 58-71).

Finally, Dr. Michelson conducted a third white males against

others analysis wherein he "increased the representation of

blacks among males of unknown race by 10%." Even this indicated

no underselection of non-white males. (See pp. 15-17 of Attach

ment 1 to Defendants Post-Trial Brief) (R 205). — ^

G. Plaintiffs' Statistical Analysis

Plaintiffs' statistical data was greatly inferior to MarAd's

for one basic reason: they carelessly lumped all MarAd Head

quarters employees together without making any distinction

between job classifications. It is undisputed that MarAd has

many different types of professional and non-professional posi

tions and that basic parameters of the job types vary greatly.

Specifically, clericals and administrative positions usually

range from GS-2 entry levels to GS -7 full performance levels,

whereas professionals may enter at the GS-5 level and advance to

10/ Plaintiffs argue that the District Court was sympathetic to

their argument that Dr. Michelson's multiple pools analysis was

weakened because applicant pools with only one racial group of

applicants would not influence the results. The District Court

recognized that Dr. Michelson's additional analysis (imputing

race to the race-unknown applicants based on and thereby increas

ing the numbers of racially mixed pools), improved the results

for MarAd. Op. 23 (JA 223) (DX-120 pp. 51 and 53). Thus, use of

race known data was demonstrated to be more conservative and reliable.

13

the full performance level at GS-12. (DX-130 2 128) . The

District Court's observation that "it would be irrational to

assume equal promotability" (Op. 29) (JA 229) among the posi

tions examined by plaintiffs is plainly correct.

It is notable that when plaintiffs' studies examined more

homogeneous positions the results were favorable to MarAd. For

example, career ladder promotions are available only up to GS-12.

Plaintiffs' analysis of tenure and frequencies of promotions

(competitive and noncompetitive together) to GS-13 and 14 show that

non-white males advanced faster and more frequently than white males

though not to a statistically significant extent. (DX-4 p. 10).

The only analysis presented by plaintiffs that purported to

address qualifications were its regressions analyses. — ̂ Plain

tiffs' regression analyses, like the rest of their analytical

data, never factored in occupational classifications. As MarAd

pointed out and the District Court found, regression analyses

such as the ones proffered by plaintiffs "show[ ] little about

how the agency became the way it is" and concluded that they

11/ These regressions used information from MarAd personnel

computer tapes, supplied pursuant to defendants' Answers to

Plaintiffs' Fourth Interrogatories in June 1980 (later updated),

to attempt to identify the impact of race/sex characteristics on

salary. Despite plaintiffs' ability to prepare regression

analyses early in the case their first did not appear until one

month before trial. (See PX 4 (printouts); DX-120 Appendix C, p.

20; Deposition of J. Van Ryzin (R 202)).

14

"tell[ ] little about whether this situation came about as a

result of actionable discrimination." (Op. 30) (JA 230); (DX-

Appendix C, p. 11-14). — ^

ARGUMENT

I. Plaintiffs' Cross-Appeal

A. The District Court Properly Held That

MarAd Had Not Discriminated Against

the Certified, Compound Class________

As more fully discussed in MarAd's opening brief (pp. 34-37,

68-71, 74-75, 78-82), the District Court rejected the class members'

allegations of compound discrimination -- the cold numbers pur

portedly reflecting the "white-maleness" of MarAd's hiring and

promotional system were simply not found to have any discrimina

tory basis. In challenging this finding, the plaintiff class

again recites the same statistical analyses — reviewed and

rejected by the District Court — which purport to prove that

MarAd discriminated in favor of white males. (Plaintiffs' brief,

at pp. 17-33). However, the District Court's findings on this

issue are unassailable.

12/ The only analysis which purported to account for job clas

sifications was plaintiffs' untimely (and rejected) post-trial

submission. However, this last analysis merely identified all

positions that plaintiffs' expert identified as requiring only

"specific (rather than general) educational degrees or courses."

Affidavit of J. Van Ryzin dated April 20, 1982, at p. 4 (R 334).

It was further rife with fatal defects — job series with specific

educational requirements (e.q., accountant-series 510; operational

research analyst-series 1515) were ommitted while jobs without

such requirements (e.g., engineering techician-series 802;

statistical assistant-series 1531) were misidentified as requiring specific education. Id.; DX-3.

15

First, the statistical evidence introduced at trial clearly

demonstrated that a large portion of the compound class (e.g.,

women) were overselected for promotion. Op. at 33. (JA 233).

Consequently, any notion of compound class discrimination is absurd.

Second, the statistical evidence proffered by the class at

trial — in an effort to prove compound class discrimination —

was found to be less reliable than that presented by MarAd. Op.

at 28 (JA 228) . For instance, plaintiffs' statistical experts

failed to separately examine statistics regarding career-ladder

against non-career-ladder positions. The District Court termed

this failure "irrational", finding that such separate analyses

were an absolute requirement given the unequal promotability

between these two types of positions. Id. at 29 (JA 229). In

addition, the class members' regression analyses were accorded

"relatively little weight" by the District Court, which noted

that such a study, "repeating a static view of the agency's

distribution of salary and similar benefits, shows little about

how the agency became the way it is." Id. at 30-31 (JA 230-31).

Indeed, the District Court opined:

It is not unusual that at an established

agency like MarAd white males dominate the

higher level, higher paying jobs. Many cases

have dealt with just such a situation and

concluded that it tells little about whether

this situation came about as a result of

presently actionable discrimination.

Id. (See also MarAd's brief at pp. 34-37). — / For the same

_1_3/ The class members' expert presented three regression

analyses at trial. See Plaintiffs' brief at 28, n. 26. None of

these analyses addressed or considered how promotions requiring

specialized skills, education or training- would affect the (FOOTNOTE CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE)

16

reasons, the class members' "descriptive" statistics — providing

"snapshots" of MarAd's workforce on an annual basis — are even

less reliable than the rejected regression analyses. (See Plain

tiffs' brief at pp. 17-22) . Simply counting the number of

"groups at issue" (e.g,, white-males, black-females, etc.) in

particular GS slots, in a particular time period, tells nothing

about the underlying claim — whether any significant statistical

disparity (e.g., more white males in higher positions) was caused

by a MarAd discriminatory policy or practice during the relevant

time frame. Moreover, the class members' survival analysis,

tracking the relative promotion rates of the respective sex/race

groups (and lumping together all types of promotions), again

failed to address the minimum objective qualifications neces

sarily at issue in various promotions. See Valentino, and Trout,

supra.

Therefore, there is no evidence in the record on which to

set aside the District Court's refusal to grant relief to the

compound class.

13/ (FOOTNOTE CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS PAGE)

statistical promotabilities. Indeed, the only analysis attempting

to address these latter requirements was prepared after trial and

post-trial briefing, although even that study failed to adequately

account for objective minimum qualifications. Indeed, this last

regression analysis failed to factor in the position type at

issue, even though this information was available in the data

base. Instead, plaintiffs assumed that all positions could be

lumped together for comparison sake. Id. The District Court

properly refused to consider this untimely submission. See

generally Valentino v. U.S. Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56 (D.C.

Cir. 1982), and Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094 (D.C. Cir. 1983),

cert pet, pending, 52 U.S.L.W. 3387 (No. 83-706).

17

B. The District Court Properly Held That

MarAd Had Not Discriminated Against

Women Employees On The Basis of Sex

As noted, the District Court held that plaintiffs had "not

proven either disparate treatment or a disparate impact on the

basis of sex from the hiring and promotional practices at MarAd."

Op. at 33 (JA 233). In relying on the more probative statistical

study submitted by MarAd, the Court stated:

...women have, if anything, been selected in

disproportionately greater numbers in com

petitive appointments at MarAd. Though some

of this overselection of women disappears if

the apparent bias in favor of applicants from

within MarAd is factored in **_/ there remains

a slight, statically insignificant preference

for women. Such a result is obviously

inconsistent with a pattern and practice of

discrimination against women. And [MarAd's

expert] found only a small, statistically

insignificant difference in the time to

promotion of women in career ladder positions

and in other noncompetitive promotions....

Taken as- a whole, the evidence does not

indicate the significant difference between

the promotion and hiring rates of men and

women required either to create an inference

of discriminatory intent or a duty to validate

the selection practices of the agency . . .

J7 By use of the term "bias," the Court does

not imply that there is anything improper in

the fact that MarAd employees have a better

chance than others of being hired for higher

level jobs. In fact, one would expect that

persons already employed at MarAd would be

more likely than others to have the qualifica

tions for other positions at MarAd.

Op. at 33-34 (JA 233-34). This finding was clearly based on the

more reliable evidence proffered by MarAd. In support of its

appeal from this ruling, the plaintiff class again relies on its

18

"white-maleness" statistics discussed above. Of course that

evidence -- whether viewed by itself or in conjunction with

MarAd's more reliable evidence -- simply failed to meet the

prerequisites for proving class-wide discrimination.

C. The District Court Properly Refused To

Review Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Statistical

Analysis________________________________

The class assigns as error the District Court's refusal to

consider an untimely statistical report which they attempted to

"introduce" after trial and submission of post-trial briefs.

(Plaintiffs' brief at p. 65, n. 59). This report, they assert,

was prepared in light of this Court's decision in Valentino,

supra, which, they further claim, "clearly defined the legal

standards governing [class statistical analyses] in this circuit

for the first time . . . " ^d. This self-serving statement

fails to explain why the class failed to file this untimely

evidence during the trial -- Valentino merely held that statis

tical proof alleging class-wide discrimination in promotions and

hiring must necessarily account for the specific objective

minimum qualifications of the jobs at issue in order to meet

plaintiff's prima facie burden under Title VII. That burden, of

course, was on plaintiffs' shoulders long before this Court's

decision in Valentino. — ^

14/ Indeed this Court Tn Trout severely criticized this very

sort of post-trial effort to reopen the evidence through

introduction of yet another statistical analysis. Trout, surpa,

702 F. 2d at 1106-1107. ----- ---

19

Significantly, the "post-Valentino11 analysis was critically

flawed and still failed to account for the specific minimum

objective qualifications at issue in the promotion scheme. See

p. 14, n. 12, supra. As such, even its post-trial consideration

of this study could not have altered the District Court's adverse

sex discrimination finding. In any event, plaintiffs fail to

show that the District Court abused its discretion in refusing to

credit these belated statistics.

D. The District Court Properly Held That

The Affirmative Action Provisions Of

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 Do Not Create A

Private Right of Action______________

The class members challenge the District Court's holding

that the affirmative action provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b)

do not give rise to a private right of action. Op. at 3 7 (JA

237) (Plaintiffs' brief, pp. 66-68). However, this challenge is

only supported by the generalized legislative history cited at

length in their brief and the absence of any relevant judicial

authority.

The traditional test for creation of private rights of

action was articulated in Court v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66 (1975) and

was restated recently in this Circuit in Council of the Blind of

Del. Cty. Valley v. Regan, 709 F.2d 1521-26 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (en

banc):

First, is the plaintiff "one of the class for whose

special benefit the statute was enacted," . . .

that is, does the statute create a federal

right in favor of the plaintiff? Second, is

there any indication of legislative intent,

explicit or implicit, either to create such a

remedy or to deny one? . . . Third, is it

consistent with the underlying purposes of

20

the legislative scheme to imply such a remedy

for the plaintiff? . . . And finally, is the

cause of action one traditionally relegated

to state law, in an area basically the

concern of the States, so that it would be

inappropriate to infer a cause of action based solely on federal law?

Although analyses of this issue typically address all four

issues, "[legislative intent has proved to be the preeminent

test‘" Sorrell v. U.S. Intern. Communications Agency, 682 F.2d

981, 986 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

Generally, it is the burden of the plaintiff to demonstrate

the presence of the requisite factors -- especially the legisla

tive intent. See Shivers v. Landrieu, 674 F.2d 906, 912 (D.C.

Cir. 1981) ("without some palpable indication of legislative

intent we would be most ill-advised to discover an implied cause

of action"). Similarly in Council for the Blind of Del. Cty.

Valley, the government prevailed by demonstrating that in enact

ing the legislation at issue Congress "chose to authorize private

suits principally against the state or local government . . . rather

than the [federal agency]." _Id. at 1530-31. Plaintiffs point to

no legislative intent to create such a cause of action.

The District Court flatly rejected the notion that §2000e-

16(b) creates a private cause of action, holding

...there is no evidence that Congress intended

that this [affirmative action] obligation, as

opposed to the general obligation to be free

from discrimination, was to be privately

enforceable. Nor is it clear how such a duty

could be measured for the purpose of, e.g., awarding back pay.

21

Op. at 37 (JA). — / In rejecting plaintiffs' reliance on Cannon

v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677 (1979), the District Court

noted that a judicially-created private cause of action, such as

sought here, would raise serious questions of reviewability:

While it is difficult to determine which

individuals would have received employment

had a given workforce been free of discrimi

nation, it is impossible to determine who

would have benefited had a proper amount of

affirmative action been instituted.

Op. at 37 (JA 237). Indeed, the only other court to have addressed

this issue also refused to find a private cause of action. See

Baca v * Butz, 394 F. Supp. 888, 894 n. 11 (D.N.M. 1975).

Cannon v. University of Chicago, supra, addressed an entirely

aspect of federal civil rights law — governmental

distribution of federal funds to educational programs — under

Title IX of the 1972 amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Here, however, it is the government's own role as employer that

is at issue. Pursuant to the various administrative and judicial

procedures expressly provided in Title VII, an aggrieved federal

employee, (or class of employees) has wholly adequate remedies

_15/ In making its findings on this issue, the District Court

also found that judicial review of MarAd's affirmative action

obligations was available under the narrow and limited provisions

of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.’C. § 701 et seq. Op.

at 37-39 (JA 237-39). However, the Court deferred ruling on the

merits of APA review and, subsequently, incorporated certain

aspects of the affirmative action issues into its relief orders.

It did specifically find that plaintiffs had failed to prove that

MarAd's affirmative action plan was "arbitrary and capricious."

Sea 559 F. Supp. at 951; see also Inj. at 7 (JA 260).

22

where he or she has suffered discriminatory treatment. Where

Congress has expressly provided for such relief in the federal

sector, the Courts should refuse to create additional remedies.

See e.g., Bush v. Lucas, ____ U.S. ____, 103 S. Ct. 2104 (1983)

(courts will not create direct, constitutional cause of action

for aggrieved federal employees where Congress established

specific scheme for review under the Civil Service Reform Act of

1978).

The District Court's ruling on this issue was therefore

correct and should be affirmed.

E. The District Court Properly Limited

The Class Relief To The Extent

Challenged By Plaintiffs___________

The plaintiff class challenges three aspects of the District

Court's relief order. (Plaintiffs' brief pp. 69 and 70) These

challenges center on (1) the tolling of the statutory limitations

period for non-prevailing class members to file individual

discrimination complaints in the future; (2) the preclusive

effect of the District Court's adverse class rulings on non

prevailing class members who might later raise individual dis

crimination claims; and (3) the scope of prevailing class relief.

These claims are without merit.

First, plaintiffs apparently argue that members of the non

prevailing class are not time-barred from filing individual

complaints of their own where, in relying on the pendency of the

class action, they failed to previously file such claims. In

effect, they assert that the pendency of the class action tolled

23

the limitation period set forth in 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5. See

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, ___ U.S. ___, ___ S. Ct. ___,

76 L.Ed.2d 628 (1983); — ̂ see also Zipes v. Trans World Airlines,

Inc., 455 U.S. 385 (1982) (filing requirements of Title VII are

not jurisdictional but are statutorily limited).

In order to protect these as yet unfiled claims, plaintiffs

unsuccessfully moved the District Court to amend its relief order

(pursuant to Rule 59(e), F.R. Civ. P.) so that nonprevailing

class members would receive notice of their right to pursue

individual complaints of discrimination independently of the

class action. This question, of course, is entirely speculative

and premature where such unidentified individual claims have yet

to make their way to the District Court. The question of whether

such claims are time-barred, (or were grandfathered in because of

the pending class action), can only be resolved if and when such

persons actually file claims. — ^

Second, plaintiffs apparently seek a determination that the

adverse class findings are in no way binding on any non-prevailing

individual class member's claims of discrimination. They sought

to establish this declaratory ruling through their unsuccessful

motion to alter or amend the District Court's judgment. Again,

16/ Of course, Crown, Cork addressed class decertification.

17/ The basis for plaintiffs' claim is itself confusing. The

District Court did provide in its relief that plaintiffs' counsel

could, if they so chose, send out a notice to non-prevailing

women class members. The only condition was that MarAd was not

obligated to either provide the notice or pay the expense. Inj.

at 6 (JA 259). While not part of the record, such a notice was sent out by plaintiffs.

24

however, this claim is highly speculative given the lack of

identifiable, non-prevailing class members who have filed com

plaints. In any event, to the extent that individual complaints

are later filed by non-prevailing class members and rely on the

same claims and/or evidence raised during the class proceedings,

such persons are not entitled to any relief based on the doctrine

of res .judicata. See EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

698 F .2d 633, 674-75 (4th Cir. 1983), cert, granted sub. nom.,

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. 52 U.S.L.W. 3342

(October 31, 1983) (No. 83-185). — ̂ See also, Mervin v. F.T.C.,

591 F.2d 821, 830 (D.C. Cir. 1978).

Third, plaintiffs assert that, in establishing the scope of

prevailing class relief, the District Court (1) erred in apparent

ly relying upon the individual complaint regulations (5 C.F.R.

§1613.214 (a)) -- providing a 30-day throw-back period for filing

individual, prevailing class claims -- rather than the class com

plaint regulations (5 C.F.R. § 1613.602), which set forth a 135-day

throw-back period, and (2) was correct in permitting prevailing in

dividual class claims to go back two years prior to the filing of the

administrative complaint. (Plaintiffs' brief at 70). With regard to

the first claim, MarAd has already noted in its brief (pp. 83-84)

that the class complaint regulations are, in fact, the appropriate

provisions for any relief here. However, as also set forth in

MarAd' s earlier brief, (id.) the District Court erred in providing

relief for claims arising prior to March 21, 1977 -- 135 days prior

to the filing of the administrative class complaint in this case.

T57 The Supreme Court has recently granted certiorari in that

case in order to address this very issue.

25

II. MarAd's Appeal

A. The District Court Erred In Certifying

The Compound, Across-the-Board Class

In its opening brief, MarAd extensively examined the District

Court's error in certifying (and subsequently failing to modify)

the compound, across-the-board class. (Brief at pp. 45-63).

Several arguments raised by plaintiffs on this issue require a

response.

First, plaintiffs claim that they satisfied the concededly

strict requisites of Rule 23, F.R.Civ. P. at the original class

certification hearing. Impliedly, they claim that any subsequent

modification of the certified class was improper because "the

propriety of a class certification [is not judged] by hindsight."

Plaintiffs' brief at p. 44, quoting Falcon, 457 U.S. at 160.

However, this argument totally misses the point of MarAd's

appeal. Notwithstanding the impropriety of the District Court's

original certification, — its subsequent refusal to modify the

class in any manner — in light of MarAd's twice demonstrating

the inherent conflicts, untypical and uncommon claims raised in

the class — flies in the face of the Supreme Court's ruling in

Falcon. It is not hindsight upon which MarAd raises this appeal

but, instead, the District Court's failure to (1) specifically

19/ At the original certification hearing, plaintiffs merely

introduced unsponsored raw data lacking any statistical analysis or significance. (R. 333).

26

address and resolve the strict requirements of Rule 23 at the

original certification stage, and (2) modify or otherwise limit

the plaintiff class before trial so that MarAd could properly

address the issues at trial. In the former situation, the

District Court's class certification order is devoid of any such

analysis, and merely sets forth the compound class' definition.

(JA 152) In the latter, the District Court's failure deprived

MarAd of an opportunity to meet the issues squarely at trial.

Additionally, the District Court again failed to set forth the

reasons for its failure to limit the class, despite extensive

documentation supporting the need to do so.

Second, contrary to plaintiffs' claim, (Brief pp. 44-46) the

Supreme Court in Falcon effectively ruled that across-the board

classes — at least those raising inconsistent and conflicting

claims such as present here — are legally deficient given Rule

23's strict requirements. Id. 457 U.S. at 155-56. See also East

Texas Motor Freight System, Inc, v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 295

(1978) . If anything, Falcon and East Texas Motor Frieght were

based on class certifications presenting fewer and simpler

inconsistencies and conflicts than are present here. — ̂ Indeed,

20/ Plaintiffs also claim that, unlike Falcon and East Texas

Motor Freight, the District Court here held an evidentiary

hearing on certification, thereby legitamizing the process.

However, that claim holds little water when the record is

examined more closely — the hearing in this case centered almost

exclusively on MarAd's claim that plaintiff Lawrence was not

suitable'to represent the class. (JA 26-150). There is little,

if any, indication that the District Judge even considered the

evidence submitted by plaintiff in certifying the class. Moreover,

the District Court's failure to even generally analyze or discuss

the requirements of.Rule 23 in its certification order only

further underline the problems inherent in this case even at the

threshhold point of certification. (JA 152)

27

plaintiffs' half-heartedly rationalize that the issues in Falcon

which were fatal to certification -- inherent conflicts between

promotion claims and hiring claims -- are somehow not relevant

here. Such an argument, however, ignores a much more critical

(and fatal) factor: challenges to MarAd's promotion and hiring

systems not only raised inconsistent claims themselves, but also

raised conflicting interests within each system -- competitive v.

non-competitive, professional v. clerical, etc. Merely investi

gating "all the steps in the procedure" (Plaintiffs' brief at p.

46) begs the question where there are several very different

O 1 /procedures being challenged. —

Third, plaintiffs' discussion of Rule 23' s typicality

requirement ignores the fact that the named plaintiffs -- pro

fessional, high-ranking employees-- presented claims wholly

untypical from the main portion of the class. Instead, this lack

of typicality is justified based on their allegation that all

applicants and employees -- regardless of the concededly diverse

and specialized positions at issue -- were subject to the "same

discriminatory policies." Plaintiffs' brief at pp. 47-49. As in

Valentino, the three named plaintiffs here could not present

21/ The fatal flaw to this argument is that the District Court

Held that a statistical analysis would necessarily have to

examine separately competitive v. non-competitive promotion

procedures. Lumping the two together only further confuses the

fset-finder's inquiry. See EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond, supra. But see Lawler v. Alexander, 698 F.2d ST5 Ml i-hClrV 1983). -------

28

claims typical of the far-ranging, diverse and specialized

professional and administrative occupations concededly present at

MarAd. *

Fourth, plaintiffs' brief analysis of Rule 23's commonality

requirement again generally refers to an "overall pattern of

discriminatory practices" and "pervasive discriminatory employ

ment policy." Brief at 50-51. Such a perfunctory response to

MarAd's argument does not create or justify a class consisting of

"common" claims where the many uncommon claims are evident.

Finally, plaintiffs' analysis of Rule 23' s adequacy of

representation requirement again fails specifically to address

the inherent conflicts present in the compound class, already

discussed at length in MarAd's opening brief. (pp. 58-63).

For all the these reasons, the class certification was

improper and should be reversed. — ^

22/ Plaintiffs' further rationalize that the typicality requirement

was met because "all three named plaintiffs made out a prima facie

case of individual discrimination on the basis of evidence presented

at trial." Brief at p. 49. Notwithstanding the undisputed fact that

none of the three individually named plaintiffs were successful on

the merits (or even established a prima facie case of disparate

treatment), the proof of such claims was wholly different from the

sort of evidence necessary to establish a class-wide, disparate impact

case. See Trout, 702 F.2d at 1112. The named plaintiffs -- who.only

presented disparate treatment claims at trial -- have never indicated

that they were alleging disparate impact claims as part of their case.

23/ The significance which plaintiffs attach to the acceptance of

the class complaint by the Department of Commerce Office of Civil

Rights is greatly overstated. First, under the applicable regula

tions (5 C.F.R. t 713.604) (1977) that decision was made without

the benefit of any argument by or on behalf of MarAd. Second,

the District Court never purported to attach any significance to

that action -- there is little doubt that it had an independent

obligation under Rule 23 to review the applicable legal require

ments. Third, the final decisions of agency civil rights officers

may be supplemented or rebutted by agencies in subsequent litiga

tion. See Toney v. Block, 705 F.2d 1364, 1366 (D.C. Cir. 1983).

29

B. The District Court Erred In Finding

Partial Class (Race) Liability_____

Plaintiffs criticism (Brief pp. 56-58, 62-64) of MarAd's

claim that the District Court erred in finding partial class

liability — race discrimination at least below the GS-13 level

— is based on the same flawed analysis relied upon by the trial

court. While these issues have been discussed at length in

MarAd's opening brief (pp. 68-82), certain arguments raised by

plaintiffs require a brief response.

First, plaintiffs assert that the District Court's class

race discrimination finding was correct because it relied on both

the alleged subjective selection standards ( e.q., disparate

treatment) and the "facially neutral" (e.g., disparate impact)

selection criteria used by MarAd. (Brief at 56-57) In support

thereof, plaintiffs cite Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc.

673 F. 2d 798 (5th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, ___ U.S. ___, 103 S.

Ct. 451 (1982) . — However unlike Payne, the District Court

here specifically and exclusively relied upon a disparate impact

theory to find partial (race) class liability and never made a

finding of intent. 559 F. Supp. at 948-950. (JA 245-47). Conse

quently, because there has been no finding that MarAd disparately

treated its black employees in the selection process, the "same

facts" which purportedly made out the disparate impact analysis are

irrelevant when examining rejected claims of disparate treatment.

24/ Contrary to plaintiffs' assertion, the Court in Payne noted

that after the disparate impact issue was resolved adversely to

plaintiffs, the case was "dramatically" transformed because proof

of intent was "crucial." Id., 673 F.2d at 817.

30

Second, the District Court's use of a disparate impact

analysis here was clearly in error. Indeed, Pouncy v. Prudential

Ins. Co. of America, 668 F.2d 795 (5th Cir. 1982) is directly on

point where plaintiffs -- in mounting an across-the-board attack

against MarAd's entire personnel system -- sought relief even

broader and more unfocused than that sought in Pouncy. — ̂ The

fact that MarAd is a federal employer rather than a private

sector employer is a distinction without a difference. The

burden of proof requirements under Title VII are concededly the

same regardless of the defendant's identity. See generally Brown

v. GSA, 425 U.S. 820 (1977). In any event, neither the affirma

tive action provisions of the statute (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b))

nor the various regulations and executive orders promulgated

thereunder supplant plaintiffs' burden to prove their case on the

merits.

Third, even if an impact analysis were somehow appropriate,

plaintiffs' statistical evidence -- purporting to show that

MarAd's "subjective" promotion decisions had as their goal the

exclusion of blacks -- is not supported by the evidence. No

signficant disparity in the number of blacks ultimately selected

from eligibles was demonstrated. (MarAd's Brief at pp. 80-81).

25/ Plaintiffs' insistence that Pouncy not be followed in this

Circuit, based on two previous cases before this Court, is

totally misplaced. In Talev v. Reinhardt, 662 F.2d 888 (D.C.

Cir. 1981), an individual plaintiff unsuccessfully challenged his

failure to receive a promotion. In McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d

62 (D.C. Cir. 1982), the plaintiff class was limited to a very

specific section of the defendant agency. Contrary to plain

tiffs' claim here, those cases do not remotely suggest that this

Court has condoned the sort of relief proscribed in Pouncy.

31

Moreover, plaintiffs' reliance on statistics focusing on the

applicant to eligible stage -- where plaintiffs see significant

racial disparity -- are legally deficient because that evidence

failed to account for the minimum objective qualifications

necessary to be considered for selection for many of the con-

cededly specialized jobs at issue. See Valentino. 674 F.2d at

67-68 and Trout, 702 F.2d at 1102.

Fourth, with regard to non-competitive (e.g., career ladder)

promotions, plaintifffs suggest that some disparity was demon

strated. However, plaintiffs never produced any analysis of

carreer ladder promotions. MarAd's analysis clearly demonstrated

that there was no statistically significant differences among the

race/sex subgroups. (DX 119, pp. 17-20). Moreover, MarAd's

competitive promotion analysis proved that blacks and women

(either together or separately) were slightly over-selected in

competing for entry into career ladders.

C. The District Court's Relief Order,

Requiring A Validation Study, was

Erroneous_________________________

In response to MarAd's claim that it could not be held

accountable for binding 0PM position selection/promotion criteria

(Brief at p. 82), plaintiffs assert that the validation study

ordered by the Court is appropriate class relief. (Brief at pp.

59-62). They base this assertion on their view that:

The starting point for the carrying out of a

competitive selection at MarAd is the drawing

up by MarAd supervisors of a position descrip

tion that describes the duties of the job in

question. This process is one involving a

degree of judgment and subjectivity and is

32

carried out at MarAd by a virtually all-white

supervisory workforce. [footnote omitted].

From the position description all else flows.

Brief at 59. Notwithstanding the District Court's refusal to

condemn the "whiteness" of the higher level positions plaintiffs'

argument actually supports MarAd's claim. First, to the extent

that MarAd subjectively treats black applicants and employees

seeking promotions in a disparate manner (as plaintiffs allege),

the District Court's liability finding -- based on a disparate

impact model -- is wholly inconsistent with this sort of relief.

Indeed, the only "facially neutral" selection standards at issue

are those found in the 0PM X-118, which were concededly not

challenged in this case. See Plaintiffs' Brief at 62, n. 56.

Where the District Court held MarAd liable under a disparate

impact theory, relief addressing the alleged subjective, inten

tionally discriminatory employment practices of MarAd -- a

disparate treatment theory -- is simply misplaced.

Second, to the extent the District Court ordered such relief

based on the binding effect of the 0PM X-118 standards (the

"facially neutral" criteria) on its selection process -- for

which there is ample evidence in the record -- MarAd simply can

not be held accountable for such standards. See Trout, 702 F.2d

at 1105-14.

Therefore, the validation study is inconsistent with the

District Court's findings and should be reversed.

33

CONCLUSION

For all the reasons stated above and in MarAd's opening

brief, the District Court's findings should be affirmed in part

and reversed in part.

STANLEY S. HARRIS,

United States Attorney.

ROYCE C. LAMBERTH,

R. CRAIG LAWRENCE,

JOHN H.E. BAYLY, JR.,

STUART H. NEWBERGER,

Assistant United States

OF COUNSEL:

TIMOTHY SHEA

Office of the Chief Counsel

Maritime Administration

U.S. Department of Transportation

Attorneys.

I

t

34

■v

%