Sit-In Cases Argued Before High Court

Press Release

October 23, 1961

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Sit-In Cases Argued Before High Court, 1961. 3a1912be-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/92928744-cd23-45c6-a376-468171855ac6/sit-in-cases-argued-before-high-court. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

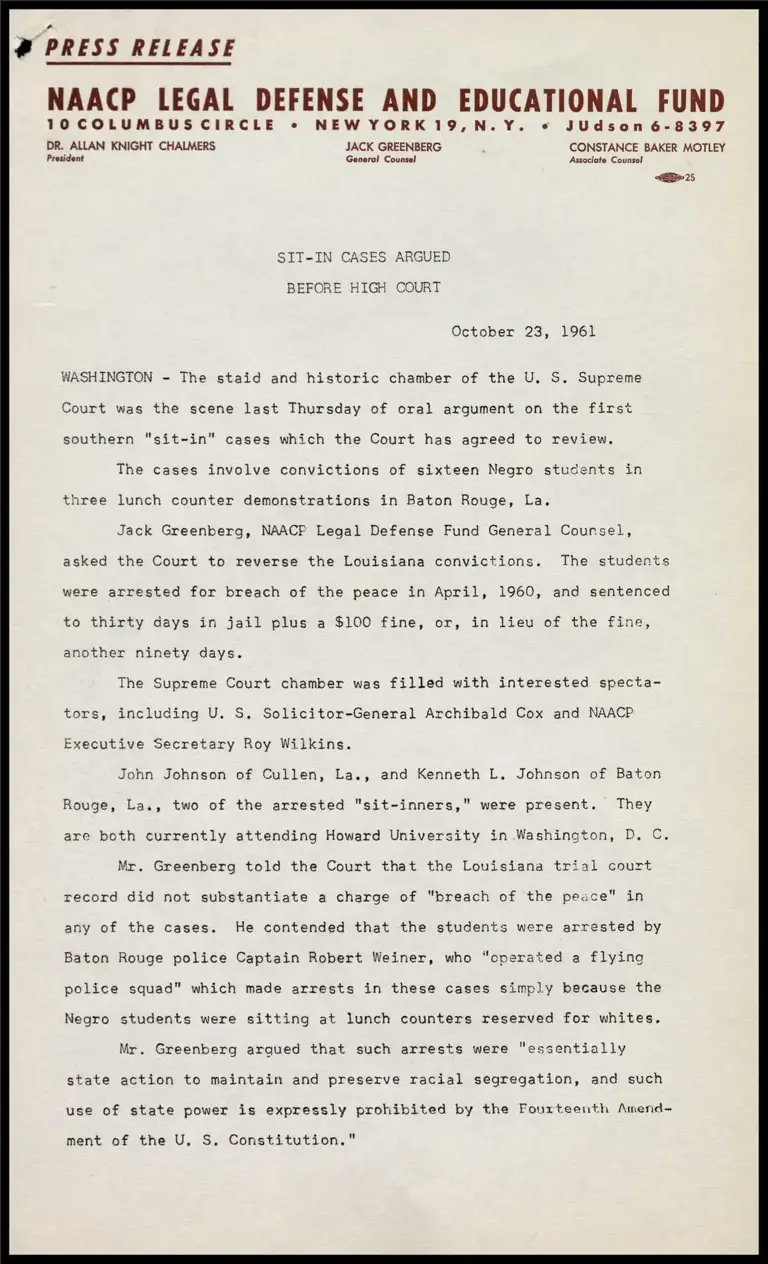

@ PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOCOLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

President General Counsel Associate Counsel

5

SIT-IN CASES ARGUED

BEFORE HIGH COURT

October 23, 1961

WASHINGTON - The staid and historic chamber of the U. S. Supreme

Court was the scene last Thursday of oral argument on the first

southern "sit-in" cases which the Court has agreed to review.

The cases involve convictions of sixteen Negro students in

three lunch counter demonstrations in Baton Rouge, La.

Jack Greenberg, NAACP Legal Defense Fund General Counsel,

asked the Court to reverse the Louisiana convictions. The students

were arrested for breach of the peace in April, 1960, and sentenced

to thirty days in jail plus a $100 fine, or, in lieu of the fine,

another ninety days.

The Supreme Court chamber was filled with interested specta-

tors, including U. S. Solicitor-General Archibald Cox and NAACP

Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins.

John Johnson of Cullen, La., and Kenneth L. Johnson of Baton

Rouge, La., two of the arrested "sit-inners," were present. They

are both currently attending Howard University in Washington, D, C.

Mr. Greenberg told the Court that the Louisiana trial court

record did not substantiate a charge of “breach of the peace" in

any of the cases. He contended that the students were arrested by

Baton Rouge police Captain Robert Weiner, who “operated a flying

police squad" which made arrests in these cases simply because the

Negro students were sitting at lunch counters reserved for whites.

Mr. Greenberg argued that such arrests were "essentially

state action to maintain and preserve racial segregation, and such

use of state power is expressly prohibited by the Fourteenth Amend-

ment of the U. S. Constitution."

Mr. Greenberg also told the Court, in answer to a question by

Justice John Harlan, that if refusing to leave a lunch counter when

ordered by a policeman constituted a breach of the peace, then the

Louisiana statute itself was unconstitutional, for "making the mere

presence of Negroes at a white lunch counter constitute breach of

the peace.”

John F, Ward, Jr., Asst. District Attorney in Baton Rouge,

argued for Louisiana.

Mr, Ward contended that the arrests were justified in the light

of violence in other cities where protest demonstrations had taken

place, and because of the éxisting inflammatory mood in Baton Rouge

at the time of the demonstrations. On this he was closely ques-

tioned by the Court, and was hard pressed to document his assertions.

Mr. Ward also argued that though the students were not actually

asked to leave by representatives of the three businesses involved,

their being told they "could not be served" should be interpreted

as a request to leave. He was questioned on this point by Justice

Hugo L. Black, who suggested that there was a difference between

telling the students they would not be served at the white lunch

counters and ordering them out.

The Louisiana attorney concluded his argument by asking the

Court to take judicial notice of the atmosphere in Baton Rouge,

even though there was no testimony concerning the mood of the city

in the record.

A Supreme Court decision often may not be handed down until

thirty days after argument, but in more complex cases, such as this

one, it is not unusual for the Court to deliberate longer.