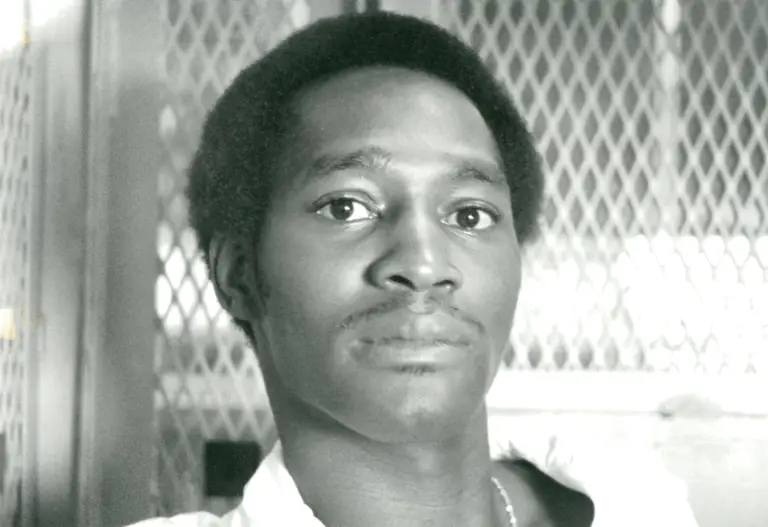

Graham, Gary, 1990s - 1 of 1

Photograph

January 1, 1990 - January 1, 2000

Wide World Photos

Cite this item

-

Photograph Collection, Criminal Justice. Graham, Gary, 1990s - 1 of 1, 1990. 1076603d-b954-ef11-a317-0022481d08e0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/932becd4-44aa-4af2-9276-e230819bbacb/graham-gary-1990s-1-of-1. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

X-TIKA:Parsed-By org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser X-TIKA:Parsed-By-Full-Set org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser Content-Length 3822190 Content-Type image/jpeg