Montero v. Meyer Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Montero v. Meyer Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1988. 993cc423-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/935cd734-7841-4c3f-b776-1676a9f6aba1/montero-v-meyer-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

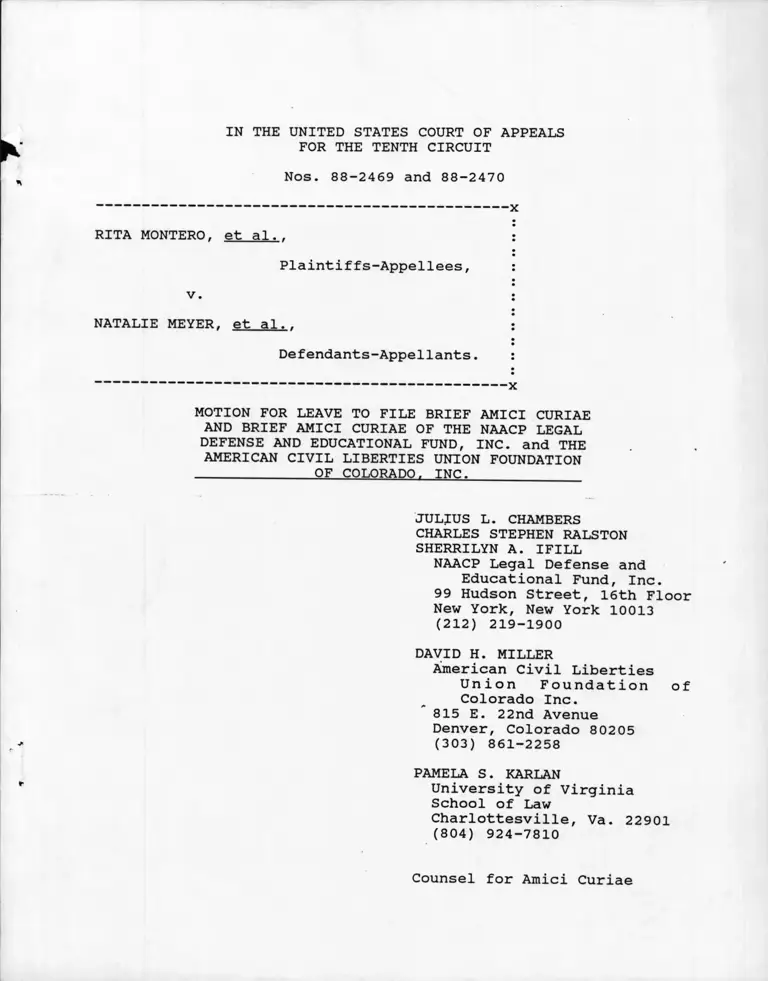

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 88-2469 and 88-2470

RITA MONTERO, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees

x

v. :

NATALIE MEYER, et al.. i

Defendants-Appellants. :

x

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. and THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION _____________ OF COLORADO. INC.____________

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON SHERRILYN A. IFILL

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

DAVID H. MILLER

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation of Colorado Inc.

815 E. 22nd Avenue

Denver, Colorado 80205

(303) 861-2258

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia School of Law

Charlottesville, Va. 22901 (804) 924-7810

Counsel for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities..................................... ii

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae ........... 1

Brief Amici Curiae ....................................... 1

Introduction ............................................. 1

Summary of Argument ..................................... 3

Argument ................................................. 4

I. The Voting Rights Act Covers Referenda as Wellas the Election of Public Officials ................ 4

II. The Voting Rights Act Protects the Ability of

Minority Voters to Participate in Every CriticalStage of the Electoral P r o c e s s .................... 8

Conclusion............................................... 12

Certificate of Service ................................... 13

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) . . . 5, 7

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988).......... 2

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) ........ 4

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973) ............ 8

Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd. 477 U.S. 901 (1986) 6

Lucas v. Townsend, 108 S.Ct. 1763 (1988)................... 7

NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)...................... 1

NAACP v. Hampton County, 470 U.S. 166 (1985).............. 2

NAACP, DeKalb County Chapter v. Georgia, 494 F. Supp.

668 (N.D. Ga. 1980) (three-judge court)................. 10

Nixon v. Condon 286 U.S. 73 (1932) ......................... 11

Pendleton v. Heard, 824 F.2d 448 (5th Cir. 1987).......... io

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967).................... ..

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .................. 9, 11

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953) ...................... 2,8

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).................... 1, 9

Torres v. Sachs, 381 F. Supp. 309 (1974).................. 11

United States v. McAlveen, 180 F. Supp. 10 (E.D.La.

196°)/ aff'd sub nom. United States v. Thomas,362 U.S. 68 (1960) ...............................

United States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners,435 U.S. 110 (1978) ..................................... ...... 9

Woods v. Hamilton, 473 F. Supp. 641 (D.S.C. 1979)(three-judge court) ......................................

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).................... .

Zaldivar v. City of Los Angeles, 780 F.2d 823(9th Cir. 1986) ..........................................

ii

Statutes p^Q0g

42 U.S.C. § 1971(e) ........................................

42 U.S.C. § 1973 et s e a . ...................................lr3

42 U.S.C. § 19731 (c) (1) ...................................7

42 U.S.C. § 1973aa-la......................................

Other Materials

28 C.F.R. § 51.17(a) (1987) ............................... 8

28 C.F.R. § 55.19(a)........................................

28 U.S.C. § 51.19(a) (1987) ...............................

H.R. 6400, § 11(c), 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) ........ 5

H.R. Rep. No. 439, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965).......... 9

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227 (1982).............................. 4

Hearings Before Subcomm. No. 5 of the House Judiciary

Conun. on H.R. 6400 and Other Proposals To Enforce

the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965)............ 4, 5

S. Rep. No. 94-295 (1975).................................2, 11

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982) . ’.............................. 4

iii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 88-2469 and 88-2470

RITA MONTERO, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees

x

v. :

NATALIE MEYER, et al.. i

Defendants-Appellants. :

x

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. and

THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION

OF COLORADO, INC.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ("LDF"),

is a non-profit corporation that was established to assist black

citizens in securing their constitutional and civil rights. The

Supreme Court has noted LDF's "reputation for expertness in

presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that

frequently arise in civil rights litigation." NAACP v. Button.

371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963).

Attorneys affiliated with LDF have litigated many

significant cases concerning the constitutional and statutory

rights of black individuals to register, to vote, and to

participate in the political process. LDF represented the

prevailing plaintiffs in Thornburg v. Ginales. 478 U.S. 30

(1986), the first Supreme Court decision to interpret amended

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. LDF has been particularly

involved in cases regarding the scope of the Voting Rights Act,

see, e.q., NAACP v. Hampton County. 470 U.S. 166 (1985) (changes

in election dates are covered under section 5 of the Act); Chisom

v. Edwards. 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988) (judicial elections are

covered under section 2 of the Act), and cases involving the

interaction between private and state activity, see, e.q.. Terry

Y - i_Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953) (private white primaries prohibited

by fifteenth amendment). Because of LDF's long standing

involvement and experience with voting rights cases, we believe

our views will be of assistance to the Court in resolving the

important issues presented by this case.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a nationwide non

partisan organization of more than 250,000 members dedicated to

protecting and preserving civil rights and civil liberties

guaranteed by law. The American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

of Colorado, Inc., ("Colorado ACLU") is a state affiliate of the

American Civil Liberties Union with over 3,500 members.

Since its creation over 60 years ago, the American Civil

Liberties Union, along with its affiliates, has worked to promote

insure the constitutional and statutory operation of state

and federal electoral systems. In that effort the American Civil

Liberties Union both nationally and locally has participated in

many of the nation's leading Voting Rights Act and

constitutionally based election cases. For example, in the last

10 years, the ACLU has been in front of the United States Supreme

2

Court on numerous occasions successfully arguing its clients'

rights under the Voting Rights Act. See, e.g.. McCain v.

Lybrand. 465 U.S. 236 (1984); Rogers v. Lodge. 458 U.S. 613

(1982); Berry v. Doles. 438 U.S. 190 (1978).

In addition to many other cases in federal appellate and

trial courts, the Colorado ACLU has evidenced a strong commitment

to protect the electoral rights of the citizens of Colorado. In

case after case before this court, the Colorado ACLU has pressed

the rights of those seeking to participate in the electoral

process. See. e.g. . Meyer v. Grant. ____ U.S. ___ , 108 S. Ct.

1886, 100 L.Ed.2d 425 (1988); Thornir v. Mever. 803 F.2d 1093

(10th Cir. 1986); Baer v. Mever. 728 F.2d 471 (10th Cir. 1984).

The case before the court raises fundamental issues under

the Voting Rights Act which have never been addressed in this

circuit and which sign-if icantly impact the rights of the

thousands of members of the Colorado ACLU and in fact all voters

in the state. Accordingly, the Colorado ACLU wishes to be

allowed to assist this court in its resolution of the matter.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons we move the Court for

leave to file the attached brief amicus curiae.

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

3

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

4

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 88-2469 and 88-2470

RITA MONTERO, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees

v.

x

NATALIE MEYER, et al. . :

Defendants-Appellants. :

x

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Introduction

In 1975, Congress amended the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. § 1973 et__seq. to reguire that states and political

subdivisions with a significant number of non-English speakers

provide "registration or voting notices, forms, instructions,

assistance, fandl other materials dr information relating to the

electoral— process" in the language used by those speakers. 4 2

U.S.C. § 1973aa-la (emphasis added). Pursuant to the triggering

mechanism provided by the Act, several counties in Colorado are

subject to the special bilingual provisions.

The legislative history accompanying the 1975 amendments

made clear Congress' belief that a bilingual electoral process

was critical to the ability of language minorities to protect

themselves from continued exclusion from voting, education,

housing, access to the judicial system, and employment. see,

1

e.g. , S. Rep. No. 94-295, pp. 29-30 (1975). Thus, the 1975

amendments reaffirmed the Supreme Court's century-old

characterization of the right to vote as "preservative of all

rights." Yick Wo v. Hopkins. 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886).

This case involves an electoral choice which powerfully

illustrates the relationship between voting and the preservation

of other rights. Pursuant to the detailed provisions of Colorado

law, the defendants in this case prepared a proposed initiate

amendment to the state constitution which would make English the

°fficial state language. Such an amendment, if enacted, would

mark a powerful symbolic exclusion of non-English speakers from

the official life of the state. Moreover, it could have

important practical consequences for non-English speakers as well

if it resulted in the provision of government services only in

English. Cf. Reitman v. Mulkev. .387 U.S. 369 (1967) (state

constitutional amendment passed by initiative invalidated under

fourteenth amendment because it placed state's imprimatur on

encouragement of private discrimination). The ability of the

Hispanic community to mobilize itself to respond to this proposed

amendment, as well as its ability to communicate its concerns

effectively to the non-Hispanic majority is obviously critical.

It is hardly surprising that a movement designed to begin

the process of minimizing the role of Spanish in Colorado itself

used only English. The decision of the state to sanction this

behavior, by issuing notice of the state-required hearing only in

English and by approving the use of petition forms using only

2

English, denied the Hispanic community information, in a form

reasonably calculated to give it notice, of the potential

emergence of this issue, until after the ballot access process

had been completed. Moreover, the entire episode had a further

invidious twist: the appearance of English-only materials subtly

suggested the propriety of such monolinguism in the political

process— and by extension in public life generally. Had

potential voters been confronted with a bilingual petition, they

might well have reflected on the wisdom of an amendment that

might prevent such inclusion of Hispanic voters in the future.

Thus, bilingual petition materials might well have resulted in a

mobilization of both Spanish- and English-speaking voters before

the initiative was placed on the ballot, thereby forestalling at

the outset the adoption of an amendment that might impair the

ability of non-English speaking persons to•participate fully in

public life in Colorado.

Summary of Argument

In passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973

et seq., Congress intended to prohibit racial discrimination with

regard to any election in which registered voters could

participate. Moreover, it recognized the interaction between

state election rules and the activities of private parties, and

intended to prevent states from giving effect in their election

systems to racially discriminatory actions of private parties.

In light of Congress' broad purposes, elections at which

3

voters decide issues of public policy directly through referenda

are covered by the Voting Rights Act. Moreover, petitions to get

items on the ballot and other private activity can play a central

role in the political process and thus the Act protects the

ability of minority group members to participate effectively in

pre-general election activity.

Argument

I. The Voting Rights Act Covers Referenda as Well as theElection of Public Officials

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was intended "to counter the

perpetuation of 95 years of pervasive voting discrimination,"

City of Rome v. United States. 446 U.S. 156, 182 (1980), and to

"create a set of mechanisms for dealing with continued voting

discrimination, not step by step, but comprehensively and

finally," S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 5 (1982) ["Senate Report"].

Congress hoped that once the right to vote was secured,' "many

forms of discriminaion fsic] which now exist will dissipate and

ultimately disappear." Hearings Before Subcomm. No. 5 of the

House Judiciary Comm, on H.R. 6400 and Other Proposals To Enforce

the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

89th Cong., 1st Sess. 1, 456 (1965) (statement of Rep. Jonathan

Bingham) [hereafter House Hearings] ; see also H.R. Rep. No. 97-

227, p. 14 (1982) (discussing the "observable consequence[s]" to

minority citizens of exclusion from government). In short, the

Voting Rights Act was intended to give minority citizens the

4

right to protect a range of interests by participating

effectively in the political process.

The legislative history and language of the Act show that it

was intended to protect the ability of minorities to vote in

elections involving referenda. The Act originated as H.R. 6400,

a bill drafted by the Johnson Administration and considered

during extensive hearings before the House Judiciary Committee.

The Supreme Court has given Attorney General Katzenbach's

testimony concerning the scope of the Act great weight "in light

of the extensive role [he] played in drafting the statute and

explaining its operation to Congress." United States v, Sheffield

Board of Commissioners. 435 U.S. 110, 131 & n. 20 (1978); see

Allen v. State Board of Elections. 393 U.S. 544, 566-69 (1969);

Senate Report at 17 & n. 51.

H.R. 6400 adopted by reference a definition of "voting" that

Uu^rariteed the right to cast an effective ballot "with respect to

. . . propositions for which votes are received in an election,"

see H.R. 6400, § 11(c), reprinted in House Hearings at 865

(quoting 42 U.S.C. § 1971(e)). In response to questions from

Members of Congress, the Attorney General made clear that

"Te1very election_in which registered electors are permitted to

vote would be covered" by the Act, House Hearings at 21 (emphasis

added), whether it involved the selection of public officials or

a referendum on public policy.1 As one court has noted, "the Act

1*’or example Rep. Kastenmeier noted that one alternative bill had defined "election" to include

5

applies to all voting without any limitation as to who, or what,

is the object of the vote." Haith v. Martin. 618 F. Supp. 410

"any general, special, primary election held in any

State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially for the purpose of electing or selecting a

candidate to public office, and any election held in

any State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially to decide a proposition or issue of public law. "

The following exchange then occurred:

"Mr. KASTENMEIER. First, I am wondering if you would accept that definition.

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. KASTENMEIER. Secondly, I am wondering if you

feel it might aid to put a definition of that sort in

the administration bill or whether it is unnecessary.

Mr. KATZENBACH. I don't think it is necessary. Congressman, but I cannot think of anv objection that I

would have to using that definition or something very similar to it."

House Hearings at 67 (emphasis added). Katzenbach had a similar colloquy with Rep. Gilbert:

"Mr*. GILBERT. ... You refer in section 3 of the bill [which dealt with tests and devices] to Federal,

State and local elections. Now, would that include election for a bond issue?

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. GILBERT. Now, my bill, H.R. 4427. I have a

definition. I spell out the word 'election7 on page 5 subdivision (b). I say:

"Election" means all elections, including

those for Federal, State, or local office and

including primary elections or any other

voting process at which candidates- or

officials are chosen. "Election" shall also

include any election at which a proposition or issue is to be decided.

Now, I have no pride of authorship but don't you

think we should define in H.R. 6400 [the

Administration's bill] the term 'election'?

Mr. KATZENBACH. I would certainly have no objection to it and I think it should be broadly defined.

House Hearings at 121 (emphasis added).

6

(E.D.N.C. 1985) (three-judge court) (emphasis omitted), aff'd.

477 U.S. 901 (1986).

The definitional provision of the Act, section 14(c)(1),

further shows the Act's broad coverage:

The terms "vote" or "voting" shall include all action

necessary to make a vote effective in any primary,

special, or general election, including, but not

limited to, registration, listing pursuant to this

subchapter, or other action prerequisite to voting,

casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted

properly and included in the appropriate totals of

votes cast with respect to candidates for public or

party office and propositions for which votes arereceived in an election.

42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1) (emphasis added). Thus, Congress

intended for minority voters to have the same ability to

participate effectively in referendum elections that they had to

participate in elections for the selection of representatives.

In light of this language and Congress' "intention to give

the Act the broadest possible scope," Allen. 393 U.S. at 566-67,

courts have repeatedly applied the Act to elections involving

voter approval of propositions. Most recently, in Lucas v.

Townsend, 108 S.Ct. 1763 (Kennedy, Circuit Justice 1988), Justice

Kennedy enjoined an upcoming bond referendum in Bibb County,

Georgia, because the county had not complied with the

preclearance requirement of section 5 before changing the date of

the referendum. See also, e.g.. Woods v. Hamilton. 473 F. Supp.

641, 644-45 (D.S.C. 1979) (three-judge court) (statute

authorizing localities to conduct referenda concerning the form

of local governments was subject to preclearance). Similarly,

the Attorney General's regulations, to which the Supreme Court

7

has given substantial deference, see, e.q.. Georgia v. United

States, 411 U.S. 526, 536-42 (1973), require preclearance of

changes connected to referenda and special elections, 28 C.F.R. §

51.17(a) (1987), and provide that jurisdictions covered by the

language minority provisions provide "informational materials"

and "petitions" in such languages, id. § 55.19(a).

Since referenda are covered by the Voting Rights Act,

minority voters must enjoy the same "opportunity [as] other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process," Voting Rights Act § 2(b), 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b). In this

case, the failure to provide either notice of upcoming hearings

or petitions in Spanish excluded Spanish-speaking voters from a

significant part of the process, the activity preceding

certification of the initiative and its placement on the general

election ballot.

II. The Voting Rights Act Protects the Ability of Minority

Voters To Participate in Every Critical Stage of theElectoral Process

At least since Terry v. Adams. 345 U.S. 461 (1953), which

struck down racially exclusive pre-primaries conducted by private

clubs, courts have recognized that practices that exclude

minority voters from a critical "stage of the local political

process," id̂ _ at 484 (Clark, J., joined by Vinson, C.J., Reed &

Jackson, JJ. , concurring), abridge the right to vote guaranteed

by the Fifteenth Amendment. In this case, the right to vote

protected by the Voting Rights Act was impaired because

8

minorities were effectively shut out of an integral, state-

sanctioned and state-regulated part of the process during which

the choices available in the actual election were shaped and

developed.

The legislative history of the 1965 Act expressed a clear

concern with the ability of private parties to exploit state

election procedures to deny minority voters an ability * to

Par"ticipate effectively in the political process. See H.R. Rep.

No. 439, 89th Cong., 1st Sess., p. ___ (1965), reprinted in 1965

U.S. Cong. Code & Ad. News 2437, 2441.2 After the 1982

amendments, the disparate impact of the interaction of private

and governmental action need no longer be ascribed to an

invidious motivation.3 In-light of amended section 2's focus on

"indigenous political reality," Thornburg v. Ginales. 478 U.S. at

The House Report noted that "even where some registration has been achieved, Negro voters have sometimes been

discriminatorily purged from the rolls." Id. In support of this

proposition it cited United States v. McAlveen. 180 F. Supp. 10

(E.D.La. 1960), aff'd sub nom. United States v. Thomasr 362 U.S.

68 (1960), which involved a wholesale challenge, by members of

the Citizens Council of Washington Parish, La., a segregationist

group, to the qualification of black voters in the Parish. The

McAlveen court invalidated the challenges, holding that the

actions of the individual, private defendants were taken under

color of state law because they "formed the basis of the removal

_ citizens ̂from the registration rolls by the defendant

Registrar acting in his official capacity," 180 F. Supp. at 13, citing Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

The 1982 amendments of the Voting Rights Act were intended, among other things, to prohibit practices which, "in

the context of the total circumstances of the local electoral

process, ha[ve] the result of denying a racial or language

minority an equal chance to participate in the electoral process"

regardless of whether they are designed or maintained for

discriminatory reasons. Senate Report at 16; see Thornburg v Gingles. 478 U.S. at 35.

9

79 and its emphatic rejection of a requirement that courts

scrutinize the racial animus of private participants in the

political system, see id. at 70-73 (opinion of Brennan, J.), the

question must now be whether organized private political activity

that excludes a protected class from a critical stage of the

electoral process has denied that protected class an equal

opportunity to participate.

In a variety of contexts, courts have recognized the

importance of giving full effect to minority participation in

pre-election activities. For example, NAACP. DeKalb Countv

Chapter v._Georgia. 494 F. Supp. 668, 677-78 (N.D. Ga. 1980)

(three-judge court), held that a decision by a county board of

registrars not to continue permitting private organizations to

conduct voter registration drives constituted a change in an

integral part of the voting process of DeKalb County and thus

required preclearance. The decision in Pendleton v. Heard. 824

F* 2d 448 (5th Cir. 1987), is particularly illuminating. There,

local officials decided to withdraw a bond issue rather than go

forward with a referendum brought about by a successful petition

drive conducted in large part in the black community. The Court

of Appeals found this refusal to conduct a petition—initiated

election to be a potentially discriminatory change in voting

requiring section 5 preclearance. Id. at 451.

The legislative history of the 1975 amendments also shows a

concern with the ability of Hispanic citizens to participate

effectively in pre-Election Day activity. In explaining the

10

scope of the requirement that "bilingual election materials" be

provided to non-English-speaking voters, Congress relied on the

observation in Torres v. Sachs, 381 F. Supp. 309, 312 (S.D.N.Y.

1974), that "[i]t is simply fundamental that voting instructions

and ballots, in addition to any other material which forms part

of the official communication to registered voters prior to an

election, must be in Spanish as well as English, if the vote of

Spanish-speaking citizens is not to be seriously impaired." id.

at 312, quoted in S. Rep. No. 94-295, p. 33 (1975). Accordingly,

the Torres court required the defendant there— the New York City

Board of Elections— to disseminate information through the non-

English media in order fully to include language minorities in

the political process. Similarly, the Attorney General's

regulations clearly contemplate the provision of bilingual

information regarding pre-election activities, expressly included

"petitions." 28 C.F.R. § 55.19(a).

The fact that this case involves petitions actually

circulated by private citizens cannot immunize it from scrutiny

under the Voting Rights Act. The private groups involved here

used a state-created process and received state approval to

circulate the monolingual petitions. Thus, like the private

actors in Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932) (finding state

action in statutory authorization for executive committees of

parties to define parties' memberships to exclude

blacks) and Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) (finding state

action in use of courts to enforce racially restrictive

11

covenants), the private actors here are imbued with state

authority. Cf. Zaldivar v. City of Los Angeles. 780 F.2d 823,

833 (9th Cir. 1986).

Conclusion

The language, legislative history, and judicial

interpretations of the Voting Rights Act clearly show that

Congress intended for minority voters to be guaranteed an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process, broadly

defined. Accordingly, this Court should affirm the judgment of

the district court that the failure to comport with the bilingual

election materials requirements of the Voting Rights Act must

prohibit Colorado from conducting the upcoming referendum.

October _____, 1988

Respectfully submitted

rULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

DAVID H. MILLER

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundadation

of Colorado, Inc.815 E. 22nd Avenue

Denver, Colorado 80205 (303) 861-2258

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia School of Law

Charlottesville, Va. 22901 (804) 924-7810

Counsel for Amici Curiae

12

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing Amicus Curiae

Brief was served this 6th day of October, 1988 by depositing the

same in the United States Mail,

addressed to the following:

Kenneth A. Padilla, Esq.

1753 Lafayette Street Denver, CO 80218

Henry J. Feldman, Esq.

899 Logan Street, Suite

Denver, CO 80203

Shannon Robinson, Esq.

1441 Eighteenth Street Second Floor

Denver, CO 80202

first class mail, post paid

Barry D. Roseman, Esq.

1634 Emerson Street

Denver, CO 80218

James Kreutz, Esq.

03 5655 S. Yosemite #200

Denver, CO 80128

Cathryn A. Baird, Esq.

1560 Broadway #200

Denver. CO 80202rJUk<;-

-J

v