Baker v. Beto Supplemental Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baker v. Beto Supplemental Brief for Appellants, 1973. b979bb35-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93630bf2-c77a-48d0-a28c-783a7a7486f3/baker-v-beto-supplemental-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

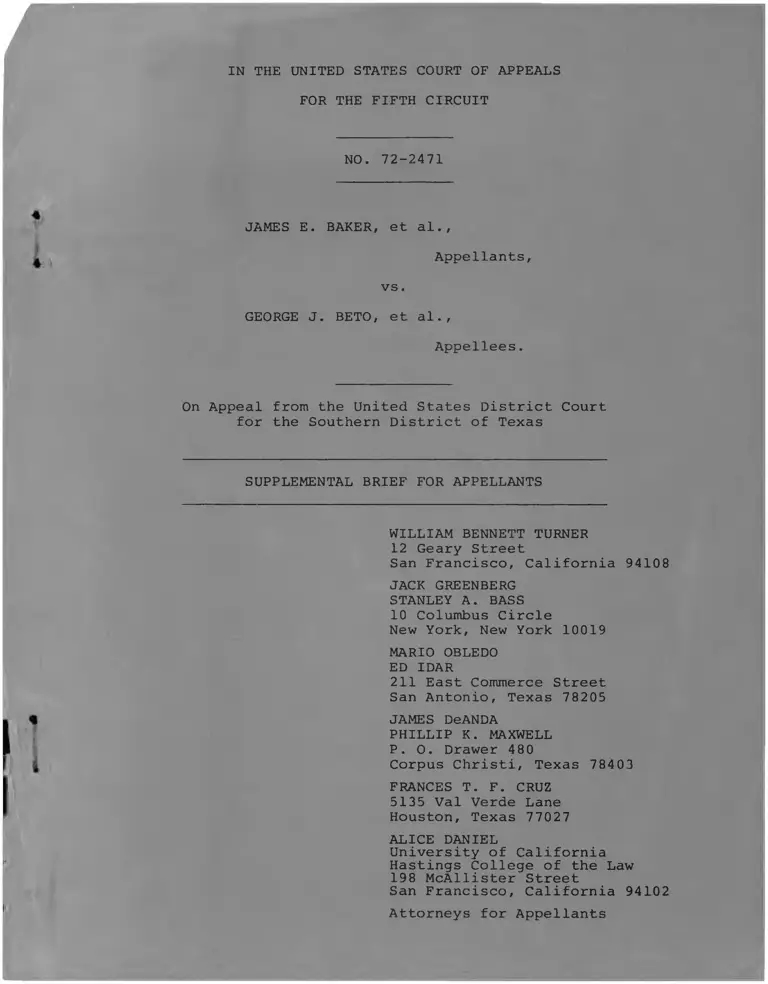

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-2471

JAMES E. BAKER, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

GEORGE J. BETO, et al. ,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Texas

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

JACK GREENBERG STANLEY A. BASS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MARIO OBLEDO

ED IDAR

211 East Commerce Street

San Antonio, Texas 78205

JAMES DeANDA

PHILLIP K. MAXWELL

P. 0. Drawer 480

Corpus Christi, Texas 78403

FRANCES T. F. CRUZ

5135 Val Verde Lane

Houston, Texas 77027

ALICE DANIELUniversity of CaliforniaHastings College of the Law198 McAllister StreetSan Francisco, California 94102

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ iii

I. Appellants' Previous Submissions .............. 1

II. Present Status Of The Case — Effect

Of Preiser v. Rodriguez ...................... 3

III. Recent Decisions Bearing On The

Issues In This C a s e ........................ .. 4

A. Due Process Safeguards .................... 4

B. Special Cases In Which Prisoners

Are Accused Of In-Prison Felonies ........ 12

C. Censorship of Attorney-Client M a i l ........ 13

D. Refusals To Mail Attorney L e t t e r s ........ 15

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . ........ . .......... 17

APPENDIX A

National Advisory Commission on Criminal

Justice Standards and Goals, Standard 2.12

(January, 1973)

APPENDIX B

Model Rules and Regulations on Prisoners

Rights and Responsibilities (May 8, 1973)

APPENDIX C

Model Rules and Regulations on Prisoners

Rights and Responsibilities (May 8, 1973)

APPENDIX D

National Advisory Commission on Criminal

Justice Standards and Goals, Standard 2.17

(January, 1973)

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

» Allen v. Nelson, 354 F.Supp. 505

(N.D. Cal. 1973) 5

Barlow v. Amiss, F.2d ,

No. 72-2401 (5th Cir. AprTTo, 1973) 14

Batchelder v. Geary, F.Supp. ,

No. C-71 2017 RFP (N.D. Cal. AprTT6, 1973) 5

Carter v. McGinnis, 351 F.Supp. 787

(W.D. N.Y. 1972) 12

Castor v. Mitchell, 355 F.Supp. 123

(W.D. N.C. 1973) 5

Chambers v. Mississippi, U.S. ,

93 S.Ct. 1038 (Feb. 21, 1973) 10

Clutchette v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767

(N.D. Cal. 1971) 12

Colligan v. United States, 349 F.Supp. 1233

(E.D. Mich. 1972) 5, 12

Collins v. Hancock, 354 F.Supp. 1253

(D. N.H. 1973) 5, 12

Crowe v. Erickson, Civ. 72-4101

(D. S.D. Dec. 1, 1972) 14

Dodson v. Haugh, 473 F.2d 689

(8th Cir. 1973) 5, 10

# Frye v. Henderson, 474 F.2d 1263

(5th Cir. 1973) 14

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, U.S. ,

93 S.Ct. 1756 (May 14, 1973) 6, 7, 9,

Gates v. Collier, 349 F.Supp. 881

(N.D. Miss. 1972) 5, 14

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) 6, 7, 10

10

iii

Page

Gomes v. Travisono, 353 F.Supp. 457

(D. R.I. 1973) 5

Goosby v. Osser, U.S. ,

93 S.Ct. 854 (1973) 3

Iverson v. Powelson, No. M33-71CA-2

(W.D. Mich. Mar. 21, 1972) 14

Jansson v. Grysen, No. G-130-71 CA

(W.D. Mich. June 5, 1972) 14

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.,

400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968) 3

In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930, 500 P.2d 873

(Sup. Ct. Cal. Sept. 15, 1972) 2, 13

Landman v. Royster, 333 F.Supp. 621

(E.D. Va. 1971) 10

Martinez v. Procunier, 354 F.Supp. 1092

(N.D. Cal. 1973) 14 , 15

McDonald v. Board of Election Commissioners,

394 U.S. 802 (1969) 3

McKenzie v. Secretary of Public Safety,

No. 71-1414 (4th Cir. Apr. 21, 1972) 14

Merritt v. Johnson, No. 38401

(E.D. Mich. Nov. 30, 1972) 14

Morris v. Affleck, No. 4192

(D. R.I. Apr. 20, 1972) 14

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972) 5, 6, 7,

Nelson v. Hayne, 355 F.Supp. 451

(N.D. Ind. 1972) 5

Nieves v. Oswald, F.2d ,

No. 72-1974 (2d Cir. Apr. 20, 1973) 12

Preiser v. Rodriguez, U.S. ,

93 S.Ct. 1827 (1973) 3, 4

iv

Page

In re Prewitt, 8 Cal.3d 470,

503 P.2d 1326 (1972) 8

Rankin v. Wainwright, 351 F.Supp. 1306

(M.D. Fla. 1972) 5

Sands v. Wainwright, F.Supp. ,

12 Cr. L. Rptr. 2376 (M.D. Fla.

Jan. 5, 1973) 5, 12

Sostre v. McGinnis, 442 F.2d 178

(2d Cir. 1971) 13

Stewart v. Jozwiak, 346 F.Supp. 1062

(E.D. Wis. 1972) 5

State ex rel Thomas v. State,

55 Wis.2d 343, 198 N.W.2d 675 (1972) 16

United States ex rel Miller v. Twomey,

___ F.2d ___, No. 71-1854 (7th Cir.

May 16, 1973) 5, 9

United States ex rel Neal v. Wolfe,

346 F.Supp. 569 (E.D. Pa. 1972) 5

Van Blaricom v. Forscht, 473 F.2d 1323

(5th Cir. 1973) 7

Washington v. Lee, 390 U.S. 333 (1968),

aff»g 263 F.Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966) 3

Worley v. Bounds, 355 F.Supp. 115

(W.D. N.C. 1973) 5, 13

v

OTHER AUTHORITIES Page

Model Rules and Regulations on Prisoners

Rights and Responsibilities, Center for

Criminal Justice of the Boston University

School of Law, May 8, 1973

National Advisory Commission on Criminal

Justice Standards and Goals, January 1973

11, 15

Standard 2.12 11

Standard 2.15 15

Standard 2.17 15

Standard 2.2 15

Turner and Daniel, Miranda in Prison: The

Dilemma of Prison Discipline and Intramural

Crime, 21 Buff. L. Rev. 759 (1972) 2

vi

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-2471

JAMES E. BAKER, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

GEORGE J. BETO, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Texas

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

In accordance with the Court's order of May 14,

1973, setting this case for en banc consideration and directing

the Clerk to require supplemental briefs, appellants file

this supplemental brief.

I. Appellants' Previous Submissions

This brief is intended only to supplement our

previous submissions, which include the following:

- 1 -

(1) Brief for Appellants, served August 11, 1972.

This is appellants' main brief and contains a thorough

statement of facts, completely documented by citations to

1/the record.

(2) Reply Brief for Appellants, served October 3,

1972, relating in relevant part to certain clearly erroneous

findings by the court below, together with copies of the

then unreported decision in In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930,

500 P .2d 873 (Sup. Ct. Cal. Sept. 15, 1972).

(3) Letter to the Clerk from counsel for appellants,

dated November 20, 1972, noting pertinent cases decided or

reported after the above briefs had been filed.

(4) Appellants' Comments On Disciplinary Procedures

Submitted By Appellees At Oral Argument, served on December 14,

1972, pursuant to leave of the Court granted at oral argument,

together with copies of a relevant law review article published

at 21 Buff. L. Rev. 759 (1972).

We respectfully urge the Court en banc to consider

all the above submissions, which fully state our factual and

legal contentions.

1/ By order of the Court dated July 25, 1972, leave to proceed

on the original record and exhibits, without an appendix,

was granted.

- 2 -

II. Present Status Of The Case — Effect Of Preiser v. Rodriguez

Since the argument before a panel of this Court,

appellant James E. Baker has been released from prison.

Fred Cruz had previously been released. We have been informed

that appellant Coy Ray Campbell has received a favorable

ruling on a habeas corpus petition, but his present status

is unclear. Of course, this action has been maintained as

a class action on behalf of all TDC prisoners, and it makes

no difference on this appeal that individual parties may have

been released. See Goosby v. Osser, ___ U.S. ___, 93 S.Ct.

854, 856, n.2 (1973); McDonald v. Board of Election Commissioners,

394 U.S. 802, 803, n.l (1969); Washington v. Lee, 390 U.S.

333 (1968), aff'g 263 F.Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966); cf.

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 33 (5th Cir. 1968).

The individual appellants originally sought, by way

of relief, restoration of their statutory good time forfeited

in disciplinary proceedings. Because of their release, Baker

and Cruz no longer seek such relief; if appellant Campbell is

released, this claim might also be moot as to him. In any

event, we recognize that the recent Supreme Court decision in

Preiser v. Rodriguez, ___ U.S. ___, 93 S.Ct. 1827 (1973),

forecloses a claim for restoration of good time unless the

prisoner proceeds via habeas corpus and alleges prior

exhaustion of state remedies. The decision in Preiser v.

Rodriguez does not, however, otherwise affect any aspect of

-3-

this case. The Supreme Court repeatedly made it clear that

only where the prisoner is challenging "the very fact or

duration" of his custody and seeks "immediate or more speedy

release" must he proceed in habeas corpus and first exhaust

state remedies. 93 S.Ct. at 1841, 1838, 1840. In cases

like the present one in which "the prisoners' claims [relate]

solely to the States' alleged unconstitutional treatment of

them while in confinement," the prisoners may properly invoke

§1983 and proceed without exhausting any possible state

2/remedies. 93 S.Ct. at 1841. The relief sought in the

present case is a declaratory judgment and an injunction

against disciplinary proceedings in which punishments are

imposed without due process, and a declaratory judgment and

an injunction against censorship of attorney-client

correspondence.

Ill. Recent Decisions Bearing On The Issues In This Case

A. Due Process Safeguards

It is now well settled, and indeed the Attorney

General has conceded as much, that before prison officials

can punish a prisoner by imposing more onerous conditions of

confinement (solitary confinement) or a longer term of

2/ In this case, the state has not contended either that there

is a state remedy or that appellants should have tried to

find one.

- 4 -

incarceration (deprivation of statutory good time and

eligibility for parole), the prisoner is entitled to a hearing

3 /meeting "minimum" standards of due process. In short, it

is settled that these consequences of prison disciplinary

proceedings are serious enough to require a hearing that will

reliably determine the facts, so that prisoners are not

arbitrarily punished. This alone requires reversal of the

decision below. The remaining question, and a question of

great importance, is precisely what are the minimum safeguards

of due process in prison disciplinary hearings.

In Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972), the

Supreme Court held that parolees are entitled to "minimum"

standards of due process before parole may be revoked, and

3/ In addition to the numerous cases cited at pages 21-24

of the Brief for Appellants, see the recent decisions in

Dodson v. Haugh, 473 F.2d 689 (8th Cir. 1973); United

States ex rel Miller v. Twomey, ___ F.2d ___, No. 71-1854

(7th Cir. May 16, 1973); Worley v. Bounds, 355 F.Supp. 115,

120-22 (W.D. N.C. 1973); Castor v. Mitchell, 355 F.Supp.

123 (W.D. N.C. 1973); Collins v. Hancock, 354 F.Supp.

1253 (D. N.H. 1973); Sands v. Wainwright, ___ F.Supp. ___,

12 Cr. L. Rptr. 2376 (M.D. Fla. Jan. 5, 1973); Rankin v.

Wainwright, 351 F.Supp. 1306 (M.D. Fla. 1972); Colligan

v. United States, 349 F.Supp. 1233 (E.D. Mich. 1972);

Gates v. Collier, 349 F.Supp. 881 (N.D. Miss. 1972);

United States ex rel Neal v. Wolfe, 346 F.Supp. 569 (E.D.

Pa. 1972); Stewart v. Jozwiak, 346 F.Supp. 1062 (E.D. Wis.

1972); Batchelder v. Geary, ___ F.Supp. ___, No. C-71

2017 RFP (N.D. Cal. Apr. 16, 1973). Cf̂ . Nelson v. Hayne,

355 F.Supp. 451 (N.D. Ind. 1972); Allen v. Nelson, 354

F.Supp. 505 (N.D. Cal. 1973); Gomes v. Travisono, 353

F.Supp. 457 (D. R.I. 1973).

-5-

specified that the following constituted such minimum

requirements:

"(a) written notice of the claimed violations

of parole; (b) disclosure to the parolee of

evidence against him; (c) opportunity to be

heard in person and to present witnesses and

documentary evidence; (d) the right to confront

and cross-examine adverse witnesses (unless

the hearing officer specifically finds good

cause for not allowing confrontation);

(e) a 'neutral and detached' hearing body

such as a traditional parole board, members

of which need not be judicial officers or

lawyers; and (f) a written statement by the

factfinders as to the evidence relied on and

reasons for revoking parole." 408 U.S. at 489.

Essentially the same safeguards were described as "rudimentary"

to due process in the Court's earlier decision in Goldberg v.

Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970). In Goldberg, the Court held in

addition that the right to retained (although not appointed)

counsel is rudimentary. The Court in Morrissey left open

whether the right to counsel is among the minimum requirements.

The Court answered this question in its recent decision in

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, ___ U.S. ___, 93 S.Ct. 1756 (May 14, 1973)

In Gagnon, the Court held that both probationers and parolees

have a right to counsel in appropriate cases. Deciding also

that all the Morrissey rights must be observed in probation

revocations, including the right to call and cross-examine

witnesses, the Court said that arguments against the right

to counsel overlook the fact that the effectiveness of the

rights guaranteed by Morrissey may "depend on the use of

skills which the probationer or parolee is unlikely to possess,

- 6 -

and referred to the obvious fact that "unskilled or uneducated"

persons like prisoners cannot realistically be expected to

protect their own interests without help from a "trained

advocate." 93 S.Ct. at 1762-3. While the Court stopped short

of holding that counsel must be appointed in all cases, it

required counsel at least in cases in which the prisoner

makes a timely and colorable claim that (1) he did not commit

the alleged violation or (2) there are substantial mitigating

or justifying factors and the evidence is complex or difficult

to present; the agency must also advise the prisoner of the

right to request counsel, consider whether he "appears to be

capable of speaking effectively for himself," and document

the reason for any refusal to afford counsel. 93 S.Ct. at

1764 .

We submit that the "minimum" safeguards of Morrissey,

Gagnon and Goldberg are also the "minimum" required in prison

4/

disciplinary proceedings. The Attorney General has suggested

no reason why any of these safeguards is not required here.

It must be recognized that the consequences of disciplinary

4/ In VanBlaricom v. Forscht, 453 F.2d 1323 (5th Cir. 1973),

this Court held that the failure of a parole board to

permit the prisoner to cross-examine adverse witnesses

violated his due process rights. The court also held

that the board had failed to state adequately the reasons

for its decision and that this violated the prisoner's

right under Goldberg v. Kelly, even though the prisoner

had been represented by counsel at the hearing.

-7-

proceedings can result in much greater deprivation of liberty

than parole revocation. A Texas prisoner who is "convicted"

of a serious offense in a disciplinary proceeding can forfeit

several years of good time in a single disciplinary proceeding

(correspondingly increasing his actual period of imprisonment),

or can be made ineligible for parole, but a parole revocation

may have less serious consequences. For example, a prisoner

might forfeit three years of good time as disciplinary

punishment while a parolee with only, say, a year to serve

on his maximum sentence would lose only that period in a

parole revocation. Nor has the Attorney General here

identified anything in the nature of disciplinary proceedings

or in the respective interests of the State or the prisoner

that makes a Morrissey-Gagnon "minimum" safeguard dispensable

5/

in resolving disputed facts in the present context.

5/ In In re Prewitt, 8 Cal.3d 470, 503 P.2d 1326 (1972), the

California Supreme Court held that a prisoner faced with

rescission of a parole grant order is entitled to all

of the Morrissey protections. The court perceived "no

significant distinction" between the situation of the

parolee faced with revocation of conditional liberty and

the unreleased prisoner faced with rescission of the right

to achieve such liberty. 8 Cal.3d at 474, 503 P.2d at 1330.

Prewitt thus requires in-prison Morrissey hearings in all

disciplinary cases in which the inmate has received a

parole date but has not been released. The California

Supreme Court carefully considered the state's interest in

summary proceedings and found that the prisoner's interest

in fair procedures prevailed. There is no distinction

between disciplinary cases in which the prisoner has

received a parole date and those in which he is prohibited

from receiving one if found guilty of the disciplinary

offense. In Texas, a prisoner found guilty of a disciplinary

offense may be demoted to a class in which he is absolutely

ineligible for parole (R. 399, p. 5; R. 237, 319).

In United States ex rel Miller v. Twomey, ___ F.2d

___, No. 71-1854 (7th Cir. May 16, 1973), the Seventh Circuit,

after carefully examining the interests of the state and the

prisoners in several disciplinary cases, held that Morrissey

requires due process protections before imprisonment can be

prolonged or punitive segregation imposed in disciplinary

6/hearings. However, the court declined, over a vigorous and

persuasive dissent by Chief Judge Swygert, to require all of

the Morrissey safeguards, and the court left the precise form

of relief to the district courts on remand. The majority of

the Seventh Circuit panel did recognize that "in the end we

may simply transplant the Morrissey requirements" to prison

disciplinary hearings (slip op., p. 27, n.37). The panel

said the district courts could require all the Morrissey

safeguards, but directed the lower courts to hold special

hearings on relief, first giving the officials an opportunity

to prepare new procedural regulations. We believe that,

while the district court's decision in the instant case must

be reversed, this Court, acting en banc, should not leave the

court below without precise guidance as to the "minimum" due

process safeguards. There is no point in a ruling by the

Court en banc that does not definitively settle this issue

6/ The Miller opinion was apparently prepared before the

Supreme Court's decision in Gagnon v. Scarpelli, supra,

and the court had no occasion to discuss whether counsel

would be required in appropriate cases.

- 9 -

now. As stated above, we believe all of the Morrissey

safeguards, and a limited right to counsel or counsel-

77substitute, are constitutionally mandated, and the Court

should make that clear.

These safeguards are mandated, however, only in

the relatively few disciplinary cases in which (1) the most

serious punishments may be imposed and (2) there is a genuine

dispute as to the facts. Obviously they are not required in

minor matters or in cases in which there is no dispute about

what happened. Disciplinary procedures must be adequate to

permit a determination that "they were likely to have

established the truth of the asserted violation." See Dodson

8/

v. Haugh, 473 F.2d 689, 690 (8th Cir. 1973). This cannot

be done with less than the "minimum" procedures of Morrissey,

Goldberg and Gagnon.

7/ As stated in the Brief for Appellants at pages 27-31,

counsel is required at least in cases in which a prisoner

is accused of conduct that can be prosecuted as a felony;

and any disciplinary hearing that results in a prisoner

becoming ineligible for parole certainly requires, under

the reasoning of Gagnon v. Scarpelli, that the prisoner

be represented by counsel. Counsel-substitute (a staff

member, a law student or a fellow prisoner) might be

sufficient in less serious cases.

8/ Cf. Chambers v. Mississippi, ___ U.S. ___, 93 S.Ct. 1038

(Feb. 21, 1973), where the Supreme Court relied on

Morrissey for the proposition that confrontation of

witnesses is essential to assure "the accuracy of the

truth-determining process." Of course cross-examination

may be restricted by the hearing officers "to relevant

matters, to preserve decorum, and to limit repetition."

Landman v. Royster, 333 F.Supp. 621, 653 (E.D. Va. 1971).

- 10 -

In addition to the many judicial decisions discussed

above and in the Brief for Appellants, we rely on the Standards

promulgated in January, 1973, by the National Advisory

Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. The

recommendations of this prestigious Commission completely

support our position; in particular, Standard 2.12 requires

all of the "minimum" due process safeguards we have specified.

A copy of such Standard is reproduced as Appendix A to this

brief.

In addition, on May 8, 1973, the Model Rules and

Regulations on Prisoners Rights and Responsibilities were

published by the Center for Criminal Justice of the Boston

University School of Law. The Model Rules and their useful

commentaries require all the "minimum" safeguards. The

relevant Rules, including Foreward and commentaries, are

reproduced as Appendix B to this brief. In the Foreward,

the Commissioner of Corrections of Massachusetts emphasizes

that the Rules are not simply an idealist's notion of

prisoners' rights but are "a long overdue instrument for

the development of sound correctional policy," provide "a

viable blueprint from which a sound correctional management

system can be constructed," and are "an invaluable tool" for

officials striving to build "systems that operate fairly,

thoroughly, and effectively."

- 11-

B. Special Cases In Which Prisoners Are

Accused Of In-Prison Felonies

As urged in the Brief for Appellants at pages 40-44,

special protections are required in the really serious

disciplinary cases, like the case of appellant Baker, when

prisoners are accused of in-prison felonies. In addition to

the authorities relied upon in the Brief for Appellants, there

are several recent decisions in point. In Collins v. Hancock,

354 F.Supp. 1253 (D. N.H. 1973), the court held that if the

disciplinary offense is also a felony, counsel must be

furnished and in no event can the accused prisoner's testimony

be used against him in a subsequent criminal proceeding. In

Sands v. Wainwright, ___ F.Supp. ___, 12 Cr. L. Rptr. 2376

(M.D. Fla. Jan. 5, 1973), the court followed the decision in

Clutchette v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal. 1971),

and held, in addition, that when the disciplinary offense

also constitutes a crime, the prisoner must be given "use

immunity". In Colligan v. United States, 349 F.Supp. 1233

(E.D. Mich. 1972), the court required all due process

safeguards and stated in addition that the accused has the

right not to be forced to testify. In Carter v. McGinnis,

351 F.Supp. 787 (W.D. N.Y. 1972), the court, relying on

Clutchette v. Procunier, supra, held disciplinary proceedings

unconstitutional because prisoners who elected to remain

silent were given serious disciplinary punishment. And in

Nieves v. Oswald, ___ F.2d ___, No. 72-1974 (2d Cir. Apr. 20,

- 12-

1973) , the court stated that when a prisoner faces a

disciplinary offense that also constitutes a crime, this

9 /"unquestionably raises grave constitutional issues."

C . Censorship Of Attorney-Client Mail

In addition to the authorities cited on pages 44-56

in the Brief for Appellants, numerous recent decisions undercut

the reasoning of the court below and follow the approach of the

Federal Bureau of Prisons and of other state systems in insuring

10/

the confidentiality of attorney-client mail. California's

Supreme Court has carefully considered the practicalities of

legal mail and stopped its censorship. See In re Jordan,

7 Cal.3d 930, 500 P.2d 873 (Sup.Ct.Cal. 1972). And a number

of recent federal decisions can be added to the long list of

courts that have condemned censorship of attorney-prisoner

mail. See Worley v. Bounds, 355 F.Supp. 115, 118-19

9/ The court distinguished and cast doubt on the continuing

validity of its prior decision in Sostre v. McGinnis,

442 F.2d 178 (2d Cir. 1971), on which appellees here rely.

The Second Circuit stated that Sostre cannot be read as

holding that the safeguards rejected on the facts of that

case will not be constitutionally required in other cases.

For example, the court pointed out as to cross-examination

that Sostre must be distinguished because the facts were

not in dispute there and this right is critical in cases

in which the facts are in dispute or punishment turns on

the perceptions of adverse witnesses.

10/ The Federal Bureau's regulation provides that "correspondence

addressed to an attorney shall be mailed from the institution

unopened and uninspected" and that incoming attorney

correspondence may only be opened "for the purposes of

inspection for contraband. . .in the presence of the

inmate" (see Brief for Appellants, p. 52). Similar

approaches of other state systems are described in the

Brief for Appellants and the many decisions granting

protection to attorney mail are collected at p. 54, n.58.

-13-

(W.D. N.C. 1973); Gates v. Collier, 349 F.Supp. 881 (N.D. Miss.

1972); Merritt v. Johnson, No. 38401 (E.D. Mich. Nov. 30,

lT71972); Crowe v. Erickson, Civ. 72-4101 (D. S.D. Dec. 1,

1972); Iverson v. Powelson, No. M33-71CA-2 (W.D. Mich. Mar. 21,

1972); Jansson v. Grysen, G-130-71 CA (W.D. Mich. June 5,

1972); Morris v. Affleck, No. 4192 (D. R.I. Apr. 20, 1972);

cf. McKenzie v. Secretary of Public Safety, No. 71-1414

(4th Cir. Apr. 21, 1972 )(consent decree); Martinez v.

Procunier, 354 F.Supp. 1092 (N.D. Cal. 1973)(applying First

12/

Amendment standards to general mail).

In short, the weight of authority holding that

attorney-client mail must be confidential is overwhelming.

11/ The order in Merritt is very detailed and gives careful

consideration to the practicalities of permitting officials

to inspect for physical contraband without reading the

contents of attorney mail. Outgoing mail to attorneys

may be sealed; incoming mail can be examined only for

physical contraband (using a fluoroscope, metal detector

or manual manipulation) and if an official has reasonable

grounds to suspect that illegal material is contained,

the letter can be opened, but only in the inmate's presence.

12/ This issue is still one of first impression in this

Circuit. In Barlow v. Amiss, ___ F.2d ___, No. 72-2401

(5th Cir. Apr. 30, 1973), the court held that pretrial

detainees stated a valid federal claim with regard to

censorship of legal correspondence. Pretrial detainees

are not differently situated from TDC prisoners charged

or indicted for in-prison crimes, whose attorney

correspondence is censored (see Brief for Appellants,

pp. 47-48).

In Frye v. Henderson, 474 F.2d 1263, 1264 (5th Cir. 1973),

the court remarked that "Actual censorship of attorney-

inmate mail -- be it incoming or outgoing — might very

well infringe unconstitutionally in the prisoner's rights

of access to the courts."

-14-

In addition to the judicial decisions discussed above and

in the Brief for Appellants, the Model Rules and Regulations

on Prisoners Rights and Responsibilities also provide for

such confidentiality. The relevant Rules, including their

commentaries, are reproduced as Appendix C to this brief.

Finally, the Standards of the National Advisory Commission

on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals also provide for

confidential attorney correspondence. Standard 2.17, providing

that even as to general mail "neither incoming nor outgoing

mail should be read or censored," is reproduced as Appendix D

13/

to this brief.

D. Refusals To Mail Attorney Letters

The Texas officials assert the right not only to

read attorney-client mail in all circumstances but also to

refuse to deliver legal letters that they deem not "relevant"

to the prisoner's case or "derogatory" to the officials. In

addition to the authorities discussed at pages 57-58 of the

Brief for Appellants, and by the American Bar Association in

its brief amicus curiae, the recent case of Martinez v.

Procunier, 354 F.Supp. 1092, 1097 (N.D. Cal. 1973), holds

that "statements critical of prison life and personnel cannot

13/ Included in Appendix D are related Standards:

Standard 2.15 deals with prisoners' rights to

free expression and association in general; and

Standard 2.2 deals with access to legal services

and specifically provides for confidential

attorney-prisoner correspondence.

-15-

be subject to censorship by the very people who are being

14/criticized simply to stifle such criticism." As the

American Bar Association brief points out, there is simply

no valid basis for the TDC practice of blocking attorney

letters because a guard disapproves their contents.

14/ This echoed a decision of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin,

which stated that "letters critical of prison administration

cannot be forbidden because they cause embarrassment or

inconvenience to prison authorities." See State ex rel

Thomas v. State, 55 Wis.2d 343, 198 N.W.2d 675 (1972).

In both Martinez and Thomas the courts were dealing with

general, not attorney correspondence. Legal mail of course

has a greater claim for special protection.

-16-

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the district court should be

reversed and remanded with instructions to enter a decree

substantially in accordance with the Standards of the National

Advisory Commission and the Model Rules annexed as Appendices

A, B, C and D hereto.

Respectfully submitted/

^ z z _____

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

JACK GREENBERG

STANLEY A. BASS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MARIO OBLEDO

ED IDAR

211 East Commerce Street

San Antonio, Texas 78205

JAMES DeANDA

PHILLIP K. MAXWELL

P. O. Drawer 480

Corpus Christi, Texas 78403

FRANCES T. F. CRUZ

5135 Val Verde Lane

Houston, Texas 77027

ALICE DANIEL

University of California

Hastings College of the Law

198 McAllister Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Attorneys for Appellants

-17-

A p p e n d ix - A

CO RRECTIO N S

For /Cores

STANDARD 2.12

DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES

Each corrections! cgancy immediately should 2dopt, consistent with Standard 16.2,

disciplinary procedures for each type of residential facility- it operates 2nd for the persons residing

therein. . • • • •

.Miner violations of rules of conduct are those punishable by no more than a reprimand, cr

loss of commissary, enterrammer.t, cr recreation prAdepts for not more than 2A hours. Ru.cs

governing minor vitiations should preside:

1. Staff may impose the prescribed miner sanctions 2i't-:r Informing the offender of Use

nature of Isis misconduct and giving him an opportunity to pro-.roe an explanation or

denial. . . . - • •- .oj

2. If 3 report of the violation is placed in the offender’s file, the offender should be so

notified.-

3 . Th> offender should ba provided with tine opportunity to reruest a review by an impartial

officer or heard c f the appropriateness cf the staff 2c*.ion.

4 . V.Tere the review indicates that the offender did not commit the violation or tire staffs

action was rat appropriate, ail reference to the incident should be removed from the

offender's fide. . + •

Major violations c f rules c f conduct arc those punishable by sanctions more stringent than

those for minor violations, in clu ing but net limited to, ioss of gcoc time, transfer to segregation,

or so’itarv confinement, trarsie; to a hasher lever ut institutional custocy cr any otner c.rar.ee m

status which may tcr.d to affect adversely an encoder s time 01 release or discharge. - . .

Rules governing major violations should provide for the following prehearing procedures:

1. Someone ether th.c-n the reporting officer should conduct ? complete investigation into

the facts of tire alleged misconduct to determine if there is probable cause to ccheve the •

offender committed a violation. If probable causa exists, a hearing cute srrould ba set.

• • «

2. Tire offender shou-d receive a copy c f any disciplinary report or charges cf the alleged,

violation and notice of the time and place of the hearing.

3 . Tire offender, if he desires, should receive assistance in preparing for the treating fremd •

member of the correctional staff, another Inmate, or other authorized person (inch,i-ilng

legal counsel if available). • . .

A. Jv-o sanction for the alleged violation should be imposed until after the hearing except .

that tire offcr.der m. y be segregated from the rest of the popu'a'.icn if the head'of the

institution finds that l.e constitutes a threat to other inmates, staff members, or himself.

Rules ccvenring major violations iliauid provide for c hearing on the alleged viola.ion which

should be conducted as foiiows: ' ' '

For /Cotes

CO RRECTIO N S

for.Wo res

J. The hearing should bo hole! as quickly as possible, generally not more then 72 hours after

the charges erf made.

s

2. The hearing should be Before an Impartial officer or board.

3 . The ofter.cer shoo’d be allowed to present evidence or witnesses on his behalf.

4 . Tire offender should be allowed to confront end cross-examine the witnesses against lum.

5. The offender may be allowed to select someone, including legal counsel, to assist him at

the hearing.

6. -The hearing officer c: board should be required to find substantia! crlder.cc cf cu2i

before imposing a sanation.

7 . Tl:c hearing effraar or beard should be required to render its decision in writing setting

fottir its findings as to controverted facts, its conclusion, and the sanction Imposed. If th*

decision finds that tire offender did rot commit the violation, all reference to the charge

should be removed from the offenders fire.

Rules governing major relations should provide for interna! review of the hearing officer’s or

board's decision. Such review should be 2u:o~tatic. The reviewing authority should be authorized

to accept tine decision, order further proceedings, or reduce the sanction imposed.

Commentary

The nature c f prison casrciLne ar.d the procedures utilized to Impose it are very sensitive

issues, both to correctional administrators and to committed offender;. Tire imm.csition of drastic

disciplinary measures c_n have a direct impact cn trie length cf time 2n offender serves in

confinement. The history c f inhumane and degudlrg forms of punishment, Including institutional

•'holes” where offenders arc confined without cictltmc. bedding, toilet fzcutties, 2nd other

decencies, has been adequately documented In the courts. These practices are stll widespread.

The administration of seme form of-discipline is necessary to maintain order Within 2 prison

institution. However, when that discipline violates constitutional safeguards or Inhibits or seriously i

undermines reformative efforts, it becomes counterproductive and Indefensible.

The very nature of a closed, inaccessible prison naltes safeguards against arbitrary disciplinary

power difficult. The correctional administraticr. i:as power to authorize cr deny every 2<-ect of

lhir.g from food ar.d clothing to access to toilet facilities. It is this pcv\ er. more than perhaps any

other v itiur. the correctional system, v.jtich must be brought under the “rj!e of law.”

Court decisions such as Cddbcrg v. Kc'lcy, 59? U.S. 25-1 (1970) end Morrissey r. Brewer, 4CS

U ^ . -»/l ( i 9 /_) have enab:.sited the hearing proecdure.as a basic due process requirement In

srrniticur.t administrative deprivations ct <;ic. liberty, cr prepert}'. There ties been considerably less

C:ar:ty, espcc.auy :n ti:c correctional context, of what minimal requirements must attend sucit a

hearing. Court decisions l.-\e varied In interpretation. A.i one end of the spectrum they have

pros.arc cmy adequate nci:ce cf enarves, a reasonable investigation into relevant facts, art! an

opportunity for the p;better to reply to charges. At the ether they have upheld the right to

written retreo c: c.uargcs. ::-.v:mg before an in.partia! tribunal, reasonable time to prepare defense,

riJrt to confront and crc-sv-exacrane witnesses, a decision based on evidence at tl;e l.carir.c, ar.d ’

For it'etes

CO RRECTIO N S

assistance by lay counsel (staff or inmate) plus legal counsel where prosecutable crimes are

involved.

Correctional systems on their ov.n Initiative have implemented detailed disciplinary

procedures incorporating substantia! portions of the recognized elements of administrative agency

due process. The standard largely follows this trend, emanating from botii courts and correctional

systems, toward more formaiized procedures with normal administrative due-process protections

in the administration of correctional discipline.

Due process is a concept authorizing van ine procedures in differing contexts of governmental

action. 1: dees net require in all cases the formal procedures associated with a criminal trios. On

the other hur.d. cue process dees contain seme fundamentals that should regulate ail governmental

action having a potentially harmful effect on an individual.

Basic to any system that respects fundamental fairness are three requirements: (!) that the.

individual understand what is expected of him so he may avoid the consequences of Lnarprupnete

behavior; (2) if he b charged with a violation, that he be informed of what he is accused; and ^3)

that he be given ar. opportunity to present evidar.ee in contradiction ci mitigation of the charge.

As the consequences to the individual increase, other procedural devices to assure the

accuracy of information on widen action will re based come into play. These include the right to

confront the individual mai-Jr.g the chare; of violation with an opportunity to crcss-c.x. mine Urn;

the right to assistance in presenting one's case, including Icaai coon rah. the right to z formal hearing

before an impart:;: tribunal c: officer; the rich: to have proceedings of the hearing recorded in

writing: arc the right in written findings c f tact. .

Prison discipline cun range in degree from an oral reprimand to loss o f good time or

disciplinary segregation. Where :h; punishment to b: imposed extends cr patenuaL'y extends the

period c f incarceration, or substantially charges the stares of the offender either by placing him in

disciplinary segregation cr removing him from advantageous werh assignments, the wider range of

procedural safeguards should be employed. There decisions arc critical net only to the offender'

but to the public. Sir.re these procedures are designed only to assure a proper factual basis for

governmental action, both the public and the offender have an interest in their implementation.

References

1. Council cr. the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Criminal Defendants. Pdinois Unified Code of

Corrections: Tentative Final Draft. St. Paul: West, !9 7 i, Section 335-9 and Section

540-7.

2. H.Tscltkop and Mile maim, Tne U:consdtutioi::lity o f Prison Life, 55 Va. L. Rev. 755

(19d9).

3. Lcndmon v. Royster, 10 Crim. L. Rptr. ECS 1 (E.D. Va. 1971! (Virginia case op hearing

and related procedures for Imposition c f solitary confinement, transfer to maximum

security, padlock confinement c . er i 0 d>v s and loss cf good time.)

•4. McGee. Thomas A.. ‘'Minimum S:arda:ds for • Disciplinary Decision Making.**-

. Unpublished paper prepared fer the CrJit'orr.ia Department cf Corrections. Sacra:.::::lo.

CORP.ECTIOMS

For Notes For Notes

5. Millemann. Prison bisripHnsr.’ Heerinzs end Procedure! D:;e Process - Tiic Requirement

o f a Full Adminisnerhc J/esring. 3 i Md. L. Rev. 27 (197!) arc authorities cited therein.

v

6. Morris r. Trariur.o, 310 F. Supp. 857 (D.R.!. 1970) (Due process safeguards fer discipline

involving segrcg2t.on).

7 . Soshe v. McGinnis. 442 F. 2d 178 (2d Cir. 1971) (Due process safeguards for cases of

substantial discipline).

8. South Carolina Department of Corrections. 77/e Emerging Rig?:is o f Offenders. Columbia,

1972.

9 . Turner, Es’cbiLCinz :!.c Ride o f Lev: in Iriscns: A Nenue! f jr Prisoners’ Rights'

Lingerie;:. 23 Stan. L. Rev. 473 (1971) ar.d authorities cited therein.

' Related Standards

2.2 Access to Legal Services

2.11 Rules o f Conduct -

16.2 Administrative Justice

1 6 3 Code of Offenders’ Rights

5.9 Continuing Jurisdiction of Sentencing Court

14.16 Security and Discipline

A p p e n d ix B

MODEL

RULES AND REGULATIONS

ON

PRISONERS5 RIGHTS AND

RESPONSIBILITIES

Prepared by

Professor Sheldon Krantz

Robert A. Bell

Jonathan Brant

Michael Magruder

o f llie

Center for Criminal Justice

Boston University School of Law

Sheldon Krantz. Director

B T. P A V L, ISIKH.

W E S T P U B L I S H I N G CO.

1973

FOREWORD

This com prehensive statem ent of basic inmate rights and respon

sib ilities is a long overdue instrum ent for the development of sound

correctional policy. Events of recent years have shown that many

correctional system s operate with no coherent rules and policies gov

erning inm ate behavior, or with only partially developed rules and

regulations to assist correctional adm inistrators and staffs in the per

form ance of their duties. This lack of coherent rules and policies has

been a m ajor source of strife in institutions throughout the country

and has forced the courts increasingly to become involved in the ad

m inistration of prisons.

N ow , and for the first tim e in any prison jurisdiction, correctional

adm inistrators have, w ith these Model Rules and Regulations on Pris

oners’ R ights and Responsibilities, a basic guideline by which they

can establish their own formalized procedures for m atters such as

disciplinary hearings and the resolution of inmate offenses. The scope

of th is document is far greater than proposals in these two areas, how

ever. Through its detaiied analysis and development of the areas

of substantive rights and prohibited conduct, for example, the docu

m ent provides a viable blueprint from which a sound correctional

m anagem ent system can be constructed.

Much of the unrest in the prisons of this country can be traced to

a basic inability to m aintain open channels of comm unications am ong

inm ates, staffs, and adm inistrators. These Rules provide helpful di

rections for reducing dangerous tensions by providing open lines for

the discussion and resolution of institutional problems on a continu

ing basis.

I am grateful to Professor Sheldon Krantz and the Center staff

for their work in the preparation of these Model Rules for the M assa

chusetts Departm ent of Corrections. Correctional adm inistrators

everyw here should find them to be an invaluable tool as they strive

to build or rebuild correctional system s that operate fairly, thorough

ly , and effectively.

John O. Boone

Com m issioner of Corrections

Commonwealth of M assachusetts

A pril, 1973

*

111

nmjmw

- l - •-» ' t ~ - . 1~ .'n ^ ‘. — r I ;. , ' . « - , L * t - ‘ < l~ . '* ■'-'. m m ,.M .■>. ■»i . . . ;^ , iV .t; .1 iW tii n m r V wait. ..«.■»,

PRISONERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

V. RULES AND COMMENTARY

ON DISCIPLINARY

PROCEDURES

General Introduction

Because maintenance of security

is such an omnipresent factor in cor

rectional institutions, the discipli

nary process is one of the most im

portant elements of prison life. Dis

ciplinary procedures are among the

most visible parts of the penal sys

tem because they so vitally affect the

lives, sentences, and attitudes of in

mates. As a result, the procedures

that determine how the disciplinary

process is carried out are an integral

part of the correctional system.

In writing a comprehensive set of

prison disciplinary regulations, the

Center for Criminal Justice has set

out a number of criteria for an ade

quate correctional disciplinary proc

ess which these rules attempt to sat

isfy. Primarily, rules have been de

signed which are intended, as much

as possible, to insure impartial and

fair procedures throughout the disci

plinary* process. In this regard, the

development of a comprehensive code

of offenses and punishments has

been recommended in order that pro

scribed behavior may be known by

inmates and guards alike and even-

handed treatment assured. In an

earlier section, a model of that code

has been introduced. Similarly, for

many offenses it has been required

that superior officers investigate al

legations of disciplinary infractions

brought by line officers. This is to

provide a system of review to insure

that only valid allegations of disci

plinary rule infractions be brought

to the attention of the disciplinary

board. Further, we have recom

mended changes in the composition

of the hearing board in order that

the process of decisionmaking at the

hearing stage be free of any possi

bility that the influence of command

ing personnel could affect the judg

ments meted out by the board.

Throughout our work on these

rules, we have been guided by the

due process standards for prison dis

ciplinary procedures which have

been required by decisions of the

federal courts in recent years.

These court decisions have attempt

ed to impose standards of fundamen

tal fairness which insure that the

disciplinary process can determine

guilt or innocence and impose pun

ishments with speed, accuracy, and

rationality. The U. S. Bureau of

Prisons correctly stated the attitude

which the courts have taken in re

viewing the conditions of prison dis

ciplinary procedures: “No judicial

decision precludes appropriate disci

plinary action for misconduct that is

imposed in a fair manner. Adverse

court decisions have been found

ed mainly upon what appears to have

been arbitrary and capricious ac

tions resulting in unwarranted loss

of privileges or the imposition of un

duly harsh physical conditions of

confinement.” * The courts and

commentators have begun to take a

closer look at prison disciplinary pro

cedures because of a growing sense

that current procedures and lack of

accountability invite abuse of such

power. As the President’s Commis

sion on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice argued, “It is

inconsistent with our whole system

of government to grant such uncon

trolled power to any official, particu

larly over the lives of persons. The

fact that a person has been convict

ed of a crime should not mean that

* U. S. Bureau of Prisons, Policy

Statement 700.5 Inmate Discipline (July

20. 1970).

155

MODEL RULES AND REGULATIONS

he has forfeited all rights to demand

that he be fairly treated by offi

cials.” *

In addition to being designed to

insure accountability and fairness,

these rules are developed as a work

able set of procedures which permit

all views to be presented in a mean

ingful fashion, provide the necessary

flexibility required for a set of disci

plinary' procedures, and yet can be

utilized without long delays between

allegation of misconduct and deter

mination of guilt or innocence.

At the same time, we have been

cognizant of the needs and concerns

of correctional officials for insur

ing that adequate security is main

tained. We have attempted to pro

pose rules which will insure the

requisite degree of security but

make the disciplinary process fair.

During the time that these rules

were in preparation, the Massachu

setts Department of Correction is

sued Commissioner’s Bulletin 72-1,

dated May 12. 1072. setting out re

vised disciplinary procedures, which

were to be implemented on an inter

im basis. This Bulletin establishes

procedures which are similar in

many respects to the procedures rec

ommended by these rules. For ex

ample, when violations other than

petty offenses are reported, shift su

pervisors must be notified. The

sh ift supervisors will review the dis

ciplinary report for accuracy and

completeness. Further, the proce

dures for disciplinary hearings sig

nificantly are similar to those rec

ommended here since they include

the right by inmates to call witness

es if advance notice is given, and

representation for the inmate and

the institution if desired, and a find

ing based upon reliable evidence.

However, as will be discussed infra,

the proposed rules here would change

the composition of the hearing board

and permit cross-examination, as well

as describing in greater detail the

appeal process. In addition, the

Commissioner’s Bulletin uses a sin

gle disciplinary officer to hear minor

matters with right of appeal to the

disciplinary board for de novo hear

ing. The rules proposed here would

provide for the original hearing be

fore the disciplinary board, but the

rules also recommend consideration

be given to the feasibility of replac

ing the disciplinary board altogether

with a professional hearing officer.

Finally, the proposed rules permit ex

pungement of disciplinary records if

further disciplinary infractions are

avoided for a period of time. There

is no comparable section in the Com

missioner's Bulletin.

A comparison of Commissioner’s

Bulletin 72-1 and 71-7 reveals that

the new disciplinary policy moves to

ward the goal stated here of clearly

articulated and fair procedures.

* President's Commission on Law En- Right to Treatment for Prisoners: So-

forcement and the Administration of cicty’s Right to Self-Defense, 50 Neb.L.

Justice, Task Force Report: Corrections Rev. 543 (1971).

83 (1967). Cf. Comment, A Sfctufory

Rule V - l Rulcbook

a. A rulebook containing all chargeable offenses and listing the

range of potential punishm ents for each offense, and the disciplinary

procedures to be followed, shall be compiled and given to each inmate

and m em ber of the staff. The rulebook shall be translated into Span-

156

PRISONERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

ish and all other foreign languages spoken by a significant number of

inm ates.

Commentary

The purpose of providing a rule-

book listing specific offenses and

penalties is to insure that all mem

bers of the prison community—in

cluding both inmates and guards—

understand exactly which activities

are proscribed and what the result

ant penalty may be for any offense.

The present disciplinary code for

Massachusetts enunciated in Com

missioner’s Bulletin 71-7 presents an

extremely vague, nonspecific listing

of potential offenses and in no way

attempts to correlate offense and

disposition. The proposed substan

tive disciplinary code included in

these materials, based in part on an

empirical study of the results in all

disciplinary proceedings held during

the past year at Massachusetts Cor

rectional Institutions in Walpole,

Norfolk, and Concord is an attempt

to insure that the process of initiat

ing complaints against inmates will

be based upon activities which both

officer and inmate know to be pro

scribed. The experience from other

studies indicates that formulation of

clear rules does alleviate difficulties

which arise from the enforcement of

vague or unwritten disciplinary

rules.3 Adoption of a rulebook of

prison disciplinary offenses is fur

ther recommended here because

there are indications that the com

pilation of such a rulebook will be

required by the courts as part of the

due process standards applicable to

prison disciplinary procedures.4

> Note. Administrative Fairness in 4 Sinclair v. Henderson. 331 F.Supp.

Corrections. 1559 Wisconsin L.Rev. 557. 1123 (E.D.La.1971). Cf. Lcr.drr.cn v.

Royster. 333 F.Supp. 621 (E.D.Ya.1971).

Rule V—2 Charging, Investigation, Pre-H earing Detention (Aw aiting

A ction)

a. Except for the category of petty offenses listed in the code

of offenses where slight sum m ary punishments m ay be imposed, line

officers m ust present allegations of violations of the disciplinary code

lo their superior officer. The superior officer shall investigate the

factual circum stances and shall determine w hether a charge should be

brought and which offense, if any, is appropriate to charge. If a

charge is brought, the superior will fill out the appropriate form, set

ting forth his understanding of the facts of the situation, including

date and tim e of day of the incident, naming the line officer who

brought the allegations originally, and listing the offense which is

charged. Superior officers m ay initiate complaints them selves w ith

out seeking approval from other persons.

b. A line officer bringing a complaint against an inmate who

believes that the inm ate should be placed in detention prior to the

hearing m ust im m ediately seek approval from his superior officer.

The superior officer or a higher ranking correctional officer are the

only persons who m ay approve detention before a hearing. N otice of

the detention must be sent to the superintendent of the institution

157

-----IX * I * * * - * * - * ^ * - v : t 7 - ; A ------- - . ' t - 1 . .1-l-..-*:;/ . - U —

MODEL RULES AND REGULATIONS

w ho m ust approve the detention action within tw enty-four hours

a fter it has begun. The superior officer and the superintendent shall

not approve detention before a hearing unless they determ ine that

the inm ate constitutes an immediate threat to institutional order or

the safety of particular inmates. Inm ates shall not be held in pre-

hearing detention longer than three days, the permissible period be

fore a hearing is required to be held except when the accused requests

th e autom atic three-aav continuance (See Rule V -3) or in an emer

gency situation (Rule V - l l ) which m ay m ake longer detention nec

essary.

Commentary

Charging and Investigation. When

a line officer observes conduct

which he regards as a violation of

the disciplinary rules, he has sev

eral choices: he can ignore the con

duct, let the inmate off with a warn

ing, impose summary punishment

for certain specified petty offenses,

or write up a disciplinary report.5

Because of this wide range of choices

which the line officer has, there is

always the possibility that he may

not act in a consistently fair man

ner in all situations. If that were

so, the postulated goal of evenhanded

treatment would not be approached.

The purpose of requiring that su

perior officers be the persons who

have the authority to file charges is

to insure immediate review of deci

sions alleging misconduct. It pro

vides an immediate review of the ini

tial decision to charge to insure that

it is made fairly and is based upon

an accurate appraisal of the inci

dent.®

Making mandatory charging and

investigation by a superior officer

would be an extension of the proce

dures currently dictated by the 1971

Commissioner’s Bulletin.* The Bul

letin permits such an investigation

where one is considered necessary.

By making superior officer investi

gation and charging mandatory,

Massachusetts would be following

the precedent of regulations in sev

eral other states* as well as a trend

indicated by recent court decisions

and legal commentary.9

Pre-Hearing Detention ( Awaiting

Action). The issue of pre-trial de

tention (awaiting action) of accused

5 K raft, P r i s o n D i s c i p l i n a r y P r a c t i c e s

and P r o c e d u r e s : I s D u e P r o c e s s R e

quired? 47 N.D.L.Rev. 9, 26 (1970).

* Of course, the mere existence of the

requ irem en t th a t superior officers in

v es tig a te complaints does not insure

th a t the investigation will be conducted

w ell. A study of the senior officers’ in

vestiga tion of complaints in the Rhode

Island prison indicated that the investi

gation was generally perfunctory and

inadequa te and failed to screen out poor

com plain ts. Harvard Center for Crim

inal Justice . J u d i c i a l I n t e r v e n t i o n in

Prison D i s c i p l i n e , 63 J.Crim.L.C. & P.S.

2 0 0 , 207 (1972).

' See also Commissioner's Bulletin

72-1 requiring supervisory officers to

review the complaint.

* See. e. g., Missouri State Peniten

tiary Personnel Informational Pamphlet

R u l e s a n d P r o c e d u r e s (1967); New Mex

ico Penitentiary. .Memo: C l a s s i f i c a t i o n

C o m m i t t e e e n d i t s S u b c o m m i t t e e s

(1971); Connecticut Dept, of Corrections.

Disciplinary Procedures.

9 Brant, P r i s o n D i s c i p l i n a r y P r o c e

d u r e s : C r e a t i n g R u l e s , 21 Cleve.St.L.

Rev. 83, 86 (May 1972); M o r r i s v. 77a-

vtsono, 310 F.Supp. 857, 872 (D.R.I.

1970).

-- • ■ - -• II -.r., jgr-TA ,.>• ■« •. JV-.A — -1-. ■ --Jr—* --i.

PRISONERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

inmates raises identical issues as does

the question of charging responsibil

ity. The requirement that pre-hear

ing detention be ordered by a su

perior officer and approved by the

superintendent provides some review

by superior officers of the exercise

of discretion by line officers. In the

only judicial decision which has con

sidered this issue directly, the U. S.

District Court in Rhode Island held

that pre-hearing detention could only

be ordered by a superior officer and

then only in strict conformance with

rules for preventive segregation.

Furthermore, a presumption of re

lease is to exist unless a superior of

ficer determines that the alleged vio

lations could constitute a threat to

institutional order or the safety of

particular inmates.10 Examples of

circumstances where detention would

be validly imposed are allegations of

fighting, assault, and attempted es

cape, all of which are direct threats

to institutional order or the safety

of other inmates.

i0 Morris v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp.

857 (D.R.I.1970).

R ule V -3 Notice, Time Before Hearing

a. The accused shall receive notice of proposed disciplinary ac

tion in oral form as soon as the decision to charge has been made and

in w ritten form as soon thereafter as possible. The w ritten notice

shall contain a description of the specific act of misconduct which is

alleged, the offense charged, a listing of the tim e and place for the

hearing, and a description of the procedure by which the accused can

obtain representation for the hearing.

b. The hearing shail be scheduled from three to five days after

th e w ritten notice has been given to the accused, except the inmate

m ay request the board to schedule hearings at the earliest possible

tim e. Priority in scheduling hearings shall be given to inmates who

have been detained prior to the hearing. The accused inm ate m ay ob

tain an autom atic continuance for an additional three-day period by

request to the hearing board. The hearing board may, at its discre

tion, grant additional continuances for periods of no more than three

days w hich are necessary to insure that all parties have adequate tim e

to prepare for the hearing.

Commentary

Notice. Although Commissioner’s

Bulletin 71-7 currently provides that

inmates receive written notice of the

charges against them, the Bulletin

does not set out with any specificity

what the notice must contain. Be

cause the courts 11 have been unani-

11 Nolan v. S c a f a t i , 30G F.Supp. 1 (D. S o s t r e v. R o c k e f e l l e r , 312 F.Supp. 863

Mass.1969), remanded 430 F.2d 5-1S (1st (S.D.N.Y.1971) a f j ' d in p a r t , r e v . in p a r t

Cir. 1970); C l u t c h c t t e v . P r o c u r . i c r , 325 s u b n o m . S o s t r e v. M c G i n n i s , 442 F.2d

F.Supp. 767 (X.D.Cal.1971); Bundy v. 17S (2nd Cir. 1971), c e r t . d e n . s u b nom.

Cannon, 32S F.Supp. 165 (D..\ld.l971); O s w a l d v. S o s t r e , 405 U.S. 97S (1972).

159

i j u u « *\i w . a. *•' - UZs*

I

r»fI

i

MODEL RULES AND REGULATIONS

mous In holding that the Due Process

Clause of the Constitution requires

that notice of the charges be given in

prison disciplinary proceedings, the

present nonspecific regulation in the

Commissioner’s Bulletin is inade

quate. The proposed regulation on

notice does satisfy the requirements

of due process since it makes manda

tory listing of the offense, sum

marizing the factual basis of the

charge, as well as listing the time

and place of the hearing. These re

quirements collectively should insure

that the inmate receives sufficient

information to comprehend exactly

what he did that was allegedly

against prison regulations and to be

able to prepare an adequate defense.

Time Requirements. The require

ments that the hearing be scheduled

from three to five days after writ

ten notice has been given is designed

to insure that both sides have an

adequate time to prepare for the

hearing, a basic requirement of the

minimum standard of due process

required for prison disciplinary hear

ings.1'- At the same time the pe

riod is kept short to maintain a

system of speedy hearings. In addi

tion, the inmate who desires an im

mediate hearing may request sched

uling of a hearing before the normal

three-day minimum has past. If the

Hearing Board should be reluctant

to grant discretionary continuances,

especially when the inmate has been

placed in pre-hearing detention since

pre-hearing detention is itself a dep

rivation of many privileges.

** Lcndman v. Royster. 333 F.Supp. See also Commissioner's Bulletin 72-1

621 (E.D.Va.1971); Cluickette v. Pro- requiring disciplinary board hearings

cunicr, 32S F.Supp. 767 (N.D.Cal. 1971). within 3 days.

Rule V—1 Composition of the Hearing; Board, Frequency of M eetings

a. Except when the offense charged is one of the category of

offenses listed in the code of offenses when petty or slight sum m ary

punishm ent m ay be imposed, a formal hearing must be held to deter

m ine guilt or innocence of the accused inmate.

b. The hearing shall be held before a disciplinary board com

posed of three members. Two members of the disciplinary board m ay

be em ployees of the institution except that members of the custodial

sta ff shall not sit on the board. The third member of the board shall

not be an em ployee or former employee of the department but shall

be selected from am ong a rotating group of citizens who have volun

teered to serve on disciplinary hearing boards at the behest of the

governor of the commonwealth. This individual shall serve as chair

m an of the hearing board. A minimum of two votes shall be required

for any decision by the hearing board.

c. The disciplinary board shall m eet at least tw ice per week and

a t such other tim es as are necessary to prevent undue delays in the

hearing of cases. N o person m ay sit on the hearing board if he was

in any w ay involved in the incident which was the cause of the dis

ciplinary action.

160

r - 'r '/ r T rr

i

PRISONERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Commentary

Requirements for Hearings. These

regulations expand somewhat the

requirements for holding of hear

ings set forth in the Commissioner's

Bulletin. The requirement that full

hearings be held in all cases of al

leged infringement of the discipli

nary code except for a specified cate

gory of minor offenses follows the

trends of recent case law.13 The

requirement reflects the view that

the disciplinary process will be most

fair and that inmates wiil best un

derstand the process when formal

hearings are held for most offenses.

Num ber o f Meetings. The subsec

tion requiring that at least two

meetings per week occur is carried

over from the Commissioner’s Bulle

tin with the additional proviso that

extra meetings should be held when

ever a backlog of pending cases may

threaten the speedy disposition of

cases.

Composition of the Hearing Board.

A major change from the Com

missioner’s Bulletin is the section re

quiring that at least one person from

outside the correctional system be re

quired to sit as chairman of the Hear

ing Board and that members of the

custodial staff not sit on the Board.

Both of these changes are designed

primarily to insure that the Hearing

Board is in a better position to make

a reasoned judgment about the guilt

or innocence of particular inmates.

In prisons, no less than in other

closed institutions, there should be

safeguards against the possibilities

of command influence, or other pres

sures that could influence the delib

erations of the Hearing Board. Cus

todial personnel are excluded because

they are the persons in charge of

enforcing the disciplinary rules.

When one member of the custodial

staff sits on the Hearing Board and

another brings charges, there may

be strong peer group pressures re

quiring findings of guilt against the

accused inmate. As one commenta

tor has noted, "the presence of

an outsider would give

meaning to the substantial evidence

requirement by avoiding institution

al loyalties and conflict of interest

in the decision-making’ body. More

over, his role would undoubtedly im

bue the inmates with a greater con

fidence in the fairness of the sys

tem to which they are exposed.” 14

The requirement that the chair

man of the Hearing Board be a per

son from outside the penal system

is recommended for an additional

reason besides that of insuring free

deliberations. It is hoped that crea

tion of a panel of outside laymen

who will agree to spend perhaps two

days per month sitting on discipli

nary Hearing Boards will bring new

discerning viewpoints to the disci

plinary process as well as making the

process more visible for interested

persons outside of the institutions.15

» Landman v. Royster,’ 333 F.Supp. vard Center for Criminal Justice, Judicial

621 (E.D.Va.1971); Jacob, Prison Dis- Intervention in Prison Discipline. 63 J.

cipline and Inmate Risk's, 5 Harv.Civ. Crim.L.C. & P.S. 200, 210 (1972).

Rights—Civ.Lib.L.Rev. 337 (1970). For

a case requiring a hearing before any « For a different view, see Harvard

imposition of solitary confinement see Center for Criminal Justice, Judicial In-

Biagiarclli v. Sielaff, 349 F.Supp. 913 terver.tion in Prison Discipline, 63 J.

(W.D.Pa.1972). Crim.L.C. & P.S. 200, 211 (1972). •

14 Hollen, Emerging Prisoner’s Rights,

33 Ohio St.L.J. 1. 61-62 (1972). See Har-

161

MODEL RULES AND REGULATIONS

I t is hoped that the Governor of the

Commonwealth will assist in the se

lection of a panel of interested citi

zens who will sit on the Hearing

Boards.

Because of the important deci

sions which this panel will make, it

is imperative that well qualified in

dividuals be chosen to serve. Quali

fications could include academic

training, demonstrated interest in

correctional problems and experience

in related fields. Since the time

commitment should be on the order

of two or three days per month, par

ticipation will require a serious com

mitment by members of the panel,

but it should be feasible for many

interested citizens to sene.

A series of orientation meetings

should be held after the panel is se

lected to acquaint the members with

the procedures for conducting the

disciplinary hearings.

A majority vote will be sufficient

to reach a decision. Disciplinary

hearings are not the same as jury

Irials but are more closely akin to

other administrative processes where

less than unanimous verdicts may be

reached. With the provisions for

review described in Section V-9,

there is sufficient protection for de

fendants in permitting decision by

majority vote.16

Although adoption of the Hearing

Board system described above is rec

ommended, serious consideration

should be given to another proposal

which would require statutory au

thority to implement. This proposal

would substitute for the, Hearing

Boards a professional Hearing Of

ficer.1' The Hearing Examiners

would be attorneys hired by the At

torney General of the Commonwealth

to be full-time triers of disciplinary

offenses. The corps of Hearing Ex

aminers would rotate among the var-

rious correctional institutions of the

Commonwealth spending relatively

short periods of time, e. g.. one

month, at each institution. The

Hearing Examiner would have all

necessary authority to hold discipli

nary hearings, make findings of fact,

and impose punishments.

By utilizing Hearing Examiners,

the disciplinary decision making

would be removed completely from

the employees of the institutions and

given to a professional trained in

conducting hearings. All possibility

of undue influence should be re

moved by use of impartial competent

Hearing Examiners who are not em

ployees of the Department of Cor

rection. Further study of the feasi

bility of utilizing Hearing Examin

ers is warranted.18

16 See Prison Reform Institute, Pro

posed R e g u l a t i o n s f o r C l a s s i f i c a t i o n e n d

Discipline a t V i r g i n i a C o r r e c t i o n a l I n

stitutions reprinted in U. S. H. Rep.

Comm, on Judiciary Subccmm. No. 3.

Correction Part III P r i s o n e r ’s R e p r e s e n

tation (1972).

>* This proposal is based upon a re

cent bill filed in the New York Legisla

ture Assembly Bill 6257 of the 1971-2

Regular Session.

18 Mass. Commissioner’s Bulletin 72-1

utilized a disciplinary officer to judge

minor matters which may be appealed

de novo to the disciplinary board.

Rule V -5 Evidence, Standard of Proof

a. The hearing board shall adm it all evidence which is reliable

testim ony about the facts of the incident from which the charge aris

es. H earsay evidence shall be admitted only if corroborated by other

1G2

PRISONERS’ RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

testim ony or authentication. All evidence must be given in the pres

ence of the accused inm ate if he attends the hearing.

b. The board shall not adjudicate an inmate guilty of any charge

unless persuaded by a preponderance of the evidence presented that

the inm ate com m itted the alleged act.

Commentary

The two parts of this section set

out the legal standards required for

admission of evidence and adjudica

tion of guilt.

Standards of Adm issibility of E vi

dence. Reliable evidence has been

chosen as the standard for admission

of evidence because disciplinary hear

ings, although increasingly formal

and adversarial, are not actual trials

where the rules of evidence apply.

The Disciplinary Board will be per

mitted to hear all testimony which

appears to be reliable and will assist

it in determining guilt or inno

cence.19 In effect, this means that

although such strict evidentiary ruies

as the best evidence rule need r.ot be

followed precisely, testimony of dubi

ous reliability such as rumor cannr.ot

be admitted. Most commonly, the

problem of reliability will arise in re

lation to hearsay. As the rule itself

states, hearsay can be admitted only

if some direct testimony is heard

tending to show the accuracy of the

hearsay. For example, second-level

hearsay statements by a guard that

he heard from another that the ac

cused inmate made an implicating

statement would be inadmissible un

less the guard had some direct state

ment of the accused indicating the

accuracy of the original statement

or unless someone who had heard

the original admission appears to

testify against the accused inmate.

All evidence must be presented in

the presence of an inmate who at

tends the hearing to permit the in

mate to confront his accusers.

Inmate Refusal to Attend. Un

der the current rules, failure to

attend a disciplinary hearing may