Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia v. Norris Motion of the Appellee to Dismiss Appeal or Affirm Judgment

Public Court Documents

September 3, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia v. Norris Motion of the Appellee to Dismiss Appeal or Affirm Judgment, 1971. 36368b0a-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/937b1667-96d5-4df0-9aec-d281bf05a844/board-of-visitors-of-the-college-of-william-and-mary-in-virginia-v-norris-motion-of-the-appellee-to-dismiss-appeal-or-affirm-judgment. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

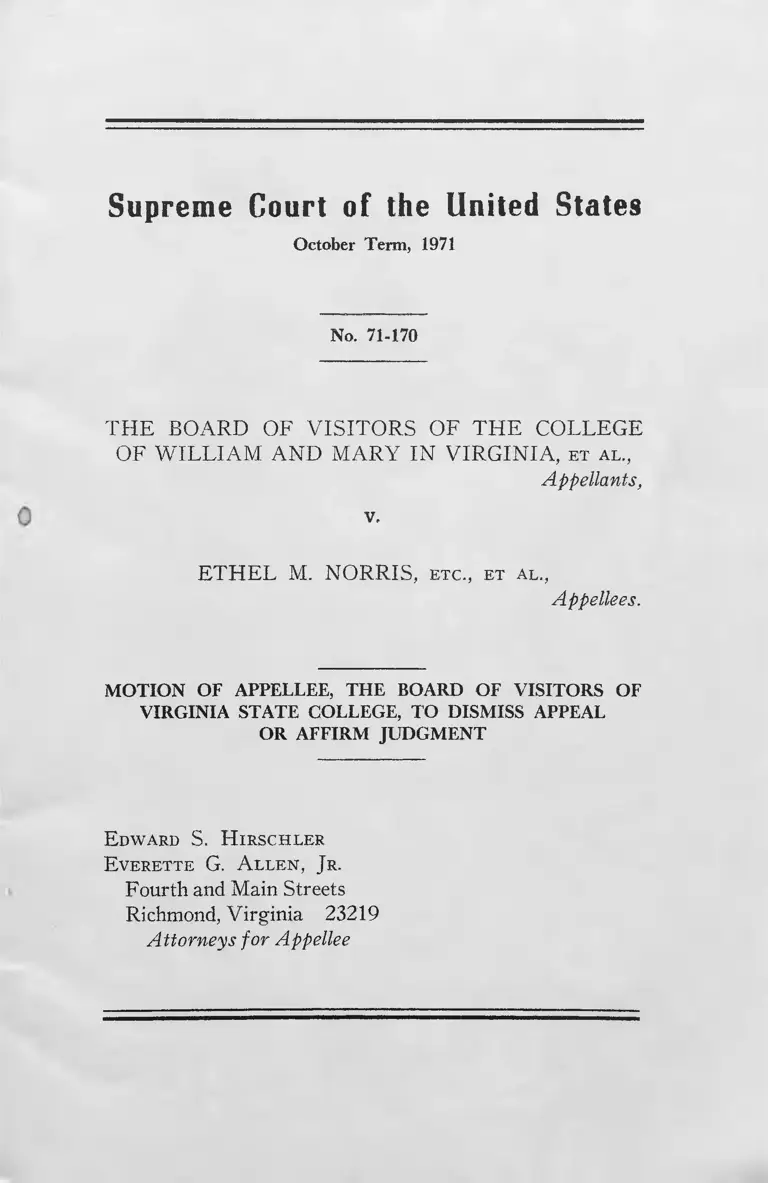

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-170

THE BOARD OF VISITORS OF THE COLLEGE

OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA, et a l .

Appellants,

v.

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc ., et a l .,

Appellees.

MOTION OF APPELLEE, THE BOARD OF VISITORS OF

VIRGINIA STATE COLLEGE, TO DISMISS APPEAL

OR AFFIRM JUDGMENT

E dward S. H ir sc h ler

E verette G. A l l e n , J r.

Fourth and Main Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of the Case......................................-........................... 1

The Decision To Be Affirmed .................-................................ 1

The Facts On Which The Opinion Is Based.... ................ ....... 3

The Findings Of The District Court ......................................- 5

The Holding ......................................... —....................... ......... 5

This Appeal ...................................................................... ....... - 6

Questions Presented......................................... ....... -................... 6

Appellee’s Position ..... ........ ............. -................ -.............. -..... 6

Appellants' Position .................................................................. 10

Conclusion ............ ........ ......... ......... -............................................ 15

Certificate of Service ....................................... ......... ................ 17

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School

and College Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala. 1968),

aff’d. per curiam 393 U.S. 400 (1969) ...............11, 12, 13, 14

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep.

117, Civ. No. 64-98 (M.D. Fla. decided March IS, 1965) .... 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....................... 3

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 317 F. Supp. 103

(M.D. Ala. 1970), modified, No. 30944 (5th Cir., decided

July 15, 1971) ...... ..................................-.................. 7, 8, 11, 15

Lungren v. Freeman, 307 F.2d 104 (9th Cir. 1962) ..................... 9

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968) -7, 9, 14

Page

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) rehearing denied, 340

U.S. 846 (1950) ........................................................................ 10

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969) ................................... ...................... ............................. 10

Zucht v. King, 260 U.S. 174 (1922) ....... ..................................... 9

Other Authorities

Boskey and Gressman, The 1967 Changes in the Supreme Court’s

Rules, 42 F.R.D. 139 ................................................................ 9

Miscellaneous

Fourteenth Amendment, United States Constitution.....................2, 6

28 U.S.C. 2281 .................................................................................. 2

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) .... ...................................... ........................... 9

Supreme Court Rules:

16-1 (c) ................................................................................... 6

16-1 (d) .................. 9

Virginia Statutes:

Acts of Assembly, 170, Ch. 461 .............................................. 2

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-170

THE BOARD OF VISITORS OF THE COLLEGE

OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA, et a l .,

Appellants,

v.

ETHEL M. NORRIS, e tc ., e t a l .,

Appellees.

MOTION OF APPELLEE, THE BOARD OF VISITORS OF

VIRGINIA STATE COLLEGE, TO DISMISS APPEAL

OR AFFIRM JUDGMENT

The Board of Visitors of Virginia State College, one

of the Appellees, moves that the judgment of the District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in the case of

Ethel M. Norris, etc., et al., v. The State Council of Higher

Education for Virginia, et al., Civil Action No. 365-70-R,

be affirmed or, in the alternative, that the appeal be dismissed

for the reasons hereinafter set forth.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Decision To Be Affirmed

On June 30, 1970, certain faculty members and students

of predominantly black Virginia State College (Virginia

State) and area high school students filed suit in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

2

Virginia. They alleged that Virginia was still operating a

racially identifiable dual system of higher education and

that a planned escalation of predominantly white Richard

Bland College (Bland) from a two year college to a four

year college would encourage and, in fact, perpetuate a

dual system in the area served by Bland and its neighbor,

Virginia State. These plaintiffs sought (i) to enjoin the

escalation of Bland, (ii) to require its ultimate merger with

Virginia State and (iii) to require state officials to prepare

a plan for the desegregation of every state-supported college

and university in Virginia. They named the Governor of

Virginia, the State Council of Higher Education, the Board

of Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia

(William and Mary), the President of Bland, and the

Board of Visitors of Virginia State as defendants. Since

the suit challenged the constitutionality of the Virginia Ap

propriations Act of 1970, Ch. 461, Item 600, p. 754 (Acts

of Assembly 1970) (the Act), which provided funds for

the escalation of Bland, the Governor of Virginia and the

State Council of Higher Education moved for a three

judge Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Section 2281. The mo

tion was granted. The District Court in an opinion by

Judge John Butzner of the Fourth Circuit, (Hoffman, J.,

dissenting), held that the provisions of the Act for Bland’s

escalation violated the Fourteenth Amendment and per

petuated a state-supported racially identifiable dual system

of higher education. The Court enjoined the Board of

Visitors of William and Mary and the President of Bland

from proceeding with escalation plans. It denied the other

relief which the plaintiffs sought.1 (App. “A”-l & 2)

1 At this writing, the case at bar has not been published in any

printed reports. It is reproduced in its entirety in the Appendix to

Appellant’s Jurisdictional Statement. It will be cited herein as (App.

“A” ).

3

The Facts On Which The Opinion Is Based

Virginia State was segregated by law as required by

Virginia’s Constitution and statutes, from its establish

ment in 1882 up to the decision in Brown v. The Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Although segregation in

education had been legally abolished, Virginia State ac

cepted no white undergraduates and employed no white

faculty members from 1954 until 1964, the same year that

control of Virginia State was transferred from the State

Board of Education to an integrated Board of Visitors. The

District Court found that since 1964 “Virginia State has

actively pursued a policy of recruiting white students and

faculty.” (App. “A”-4) Of its 2,524 students 70 or 2.7%

are white. The number of its minority students compares

favorably with other four year colleges in Virginia. For the

1970-1971 academic year, its faculty and staff numbered

255, of which 43 or 16.8% were white, 199 or 78% were

black and 14 or 5.2% were members of other races.

Bland was established in 1960 as a two year branch of

William and Mary. In the 1970-1971 academic year, 14 of

Bland’s 841 students or 1.6% were black. Not until after

the present action was filed in the District Court did its

catalog mention that it was open to all students regardless

of race. It has never had a black faculty member. Only

recently did it even try to recruit applicants from pre

dominantly black high schools or employ black faculty.

William and Mary, which, as Appellants point out, is the

second oldest college in the United States, controls the ex

penditure of appropriations, makes rules and regulations,

and is responsible for the selection of the faculty and ad

ministrative staff of Bland. All the members of the Board

of Visitors of William and Mary are white. The faculty

and administrative staff of William and Mary are white—

except for one black graduate student who has a part-time

4

administrative position. Of its 3,750 students, 51 or 1.3%

are black.

As the Court below pointed out, the Virginia Commission

on Higher Education Facilities, the State Council of Higher

Education of Virginia and the Governor of Virginia all

recommended that Bland—located just seven miles from

Virginia State—be included in the State’s two year com

munity college system. (App. “A”-5) The majority opin

ion emphasized that in “pressing for escalation, the rep

resentatives of William and Mary and Bland seek a goal

almost without precedent . . . only in one other instance has

Virginia established in the same community two full fledged

colleges offering similar curricula and degrees.” (App.

“A”-5 ) The Court below said:

“The realities of the situation support this finding:

the colleges are located close to each other; as four-

year colleges they would offer substantially the same

curricula; if Bland were escalated, white students would

be more likely to seek their degrees at predominantly

white Bland than at predominantly black Virginia

State; and the part Bland now plays in sending some

white students to Virginia State for their last two years

would substantially decrease. (Emphasis supplied.)

(A pp. “A ”-5 )

And further:

“From the evidence, it is reasonable to infer, therefore,

that the purpose and effect of Bland’s escalation is to

provide a four-year college for white students who

reside nearby. There can be little doubt that this will

contribute to the perpetuation of Virginia’s dual system

of higher education.” (App. “A”-6)

These then are the basic facts condensed from the opinion

of the Court below and, therefore, are entitled to great

weight.

5

The Findings Of The District Court

The District Court found that:

(1) “A racially identifiable dual system of higher edu

cation exists in Virginia today.” (App. “A”-3) It exists

specifically in the area served by Virginia State and Bland.

(2) “Bland already has a ten year history of an all-

white faculty and a virtually all-white student body.” (App.

“A”-8)

(3) “The racial composition of students and faculty

at Bland and William and Mary do not permit us to predict

confidently that Bland will soon shed its racial identity and

be operated as ‘just a school.’ ” (App. “A”-8)

(4) “Escalation of Bland would hamper Virginia State’s

efforts to desegregate its student body.” (App. “A”-5)

(5) “. . . the purpose and effect of Bland’s escalation is

to provide a four year college for white students who reside

nearby. There can be little doubt that this will contribute

to the perpetuation of Virginia’s dual system of higher edu

cation.” (App. “A”-6)

(6) “Virginia State’s increasingly integrated faculty of

fers a full range of courses, which Richard Bland would

largely duplicate.” (App. “A”-8)

Each of these findings has substantial and adequate sup

port in the record. None of them, on their face or on the

record, are clearly erroneous. It is within this framework

that the decision on whether or not to hear the case must

be made.

The Holding

The Court below held that the provisions of Item 600

of the Act violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con-

6

stitution of the United States. It enjoined the Board of

Visitors of William and Mary and the President of Bland

from escalating Bland. It denied other relief sought by the

Plaintiffs without prejudice, and dismissed the Governor

of Virginia and the State Council of Higher Education

for Virginia as Defendants. (App. “A”-9 & 10)

This Appeal

The Board of Visitors of William and Mary and the

President of Bland have appealed from that part of the

order declaring Item 600 of the Act violative of the Four

teenth Amendment and have submitted their Jurisdictional

Statement to this Court. Virginia State asks that the three-

judge District Court opinion be affirmed or in the alterna

tive that the appeal be dismissed.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Appellee’s Position

Virginia State contends the lower court correctly decided

the case based on its well-documented findings of fact.

Thus either the decision should be affirmed or the appeal

dismissed without reaching the broad constitutional ques

tions which appellants press upon this Court.

Supreme Court Rule 16-1 (c) provides for affirmation

of the judgment of a lower court when it is manifest that

the questions on which the decisions of the case depend are

so insubstantial as not to need further argument. The deci

sion below merely answered in the affirmative the following

question:

Did the State of Virginia, acting through its agencies,

William and Mary and Bland, violate its affimative

duty to dismantle its dual system on the college level

7

when it directed that Bland become a four year college

the result of which would be to perpetuate the dual

system■?

Virginia State submits that it has already been answered

in the affirmative by decisions in this and other courts.

There is no question that Virginia has an affirmative

duty to dismantle its dual system of higher education.

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F. Sup. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968).

Other courts have already gone far beyond the court below

in interpreting this affirmative duty. In Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, 317 F.Sup. 103 (M.D. Ala.

1970), the three judge federal court there ordered the

Alabama Junior College Authority to show cause:

“. . . why said Authority and its individual members

should not be enjoined from any further expenditure of

capital outlay funds for junior colleges until the Mobile

State Junior College has been transferred into a fully

desegregated two year institution serving primarily

Mobile and Washington Counties and is equal in

physical facilities and curriculum to the James H.

Faulkner Junior College.” (Emphasis added.) 317

F.Supp.at 111.

Going beyond merely enjoining the expansion of a two-year

college, the Court also ordered (i) immediate exchange of

faculty members between the predominantly white and

predominantly black schools, (ii) establishment of definite

attendance areas for each school, and (iii) expansion of

the curriculum of predominantly black Mobile State Junior

college to include a computer science program and expansion

of other professional programs.

The only provision of the lower court’s decree in issue on

appeal to the Fifth Circuit involved the establishment of

8

definite attendance areas. Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, No. 30944 (5th Cir., decided July 15, 1971).

After reviewing in some detail the steps taken by the State

of Alabama to comply with the other provisions of the

decree, the Court stated:

“In view of the facts presented and developments

which have taken place since the decree of the district

court (as reflected by reports filed and in the record),

we conclude to stay and postpone the effective date of

that portion of the court’s decree about which com

plaint is made on this appeal.. . . ” Id. at 8.

The Fifth Circuit further noted that:

“Uncontested on this appeal are provisions of the

decree aimed at eradicating present racial imbalance;

these include requirements for substantial faculty inte

gration, for significant improvement of physical facil

ities, and for the concomitant development and expan

sion of the curriculum at Mobile State.” Id. at 7.

Accordingly, the Alabama federal courts have required

positive action by State authorities to eliminate the dual

system in higher education, and it is submitted that these de

cisions are entirely consistent with the holding of the lower

court here. The submission that the issues Appellants seek

to raise in this Court are so insubstantial as not to need

further argument is strongly suggested by the fact that

the State authorities in Lee v. Macon County raised on

appeal only the matter of definite attendance areas, and

proceeded forthwith to comply with the other dictates of

the lower court.

The Court below stopped short of requiring the merger

of Bland and Virginia State, a remedy previously applied in

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction, 10 RACE REL.

9

L. REP. 117, Civ. No. 64-98 (M.D. Fla., decided March

15, 1965). There a predominantly white junior college was

merged with a predominantly black junior college—though

both were being operated on a non-discriminatory basis. The

Court below also stopped short of ordering the submission

of a plan for the desegregation of all state colleges and

universities as had been done in Sanders v. Ellington, 288

F.Sup. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968).

Virginia State submits that these decisions have fore

closed the constitutional question presented in the instant

case and leave no room for real controversy. There is no

substantial federal question for the court to hear, and the

decision should be affirmed. Supreme Court Rule 16-1 (c) ;

Zucht v. King, 260 U.S. 174 (1922).

Virginia State asserts that further grounds exist for

either dismissal of the appeal or affirmance of the judgment

under Supreme Court rule 16-1 (d).2

First of all, the record abundantly documented the three-

judge District Court’s finding that the escalation of Bland

would serve to perpetuate Virginia’s dual system of higher

education. The undisputed past and present history of Bland

and Virginia State—set out in the Statement of the Case

and the Opinion of the Court below—manifestly show that

this finding is not clearly erroneous. “Findings of fact shall

not be set aside unless clearly erroneous . . .” Fed. Rules

Civ. P. 52(a); Lundgren v. Freeman, 307 F.2d 104 (9th

Cir. 1962). The decision of the Court below in no way

conflicts with the decisions of this or any other court.

Secondly, since the State of Virginia and its agencies

2 Commentators have noted that this provision was designed to en

courage appellees to address themselves to factors such as those

relevant to the discretionary grant of certiorari. Broskey and Gress-

man, The 1967 Changes in the Supreme Court’s Rules, 42 F.R.D.

139,’l46.

10

have an affirmative duty to dismantle the racial identities

of white Bland and black Virginia State, it follows that

they cannot knowingly and purposely expand Bland in a

manner which will perpetuate these racial identities. This is

particularly true when there is no justification for the ex

pansion on the basis of educational policy. The Governor

and the leading educational authorities of the Common

wealth have unanimously recommended that Bland remain

a two-year institution. It is not necessary for this Court to

go beyond these facts and it is surely not necessary to de

lineate in this case what the boundaries of this affirmative

duty are. It is submitted that this Court can and should limit

itself to deciding that the decision below was correct on its

facts. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

393 U.S. 68 (1969).

Finally, the nature and role of two-year colleges like

Bland is only now evolving. Students of such schools live

in their home communities and commute to class much as in

high school. Such two-year colleges have tended to blur

the once clear-cut lines between high school and “higher

education.” Virginia State submits that it is unnecessary

for this court to delineate the constitutional distinctions be

tween secondary education and junior colleges. The decision

below can be limited to its own particular and compelling

facts, allowing this court to decide broader constitutional

questions in its own cautious tradition. Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629 (1950), rehearing denied, 340 U.S. 846

(1950).

Appellants’ Position

Appellants urge that the questions decided by the Court

below are of a substantial nature requiring briefs on the

merits and oral arguments. On page 13 of their Jurisdic

tional Statement they give the following reasons:

11

(1) “. . . the question presented in the case at bar

is precisely identical to that decided in diametrically

opposite fashion . . . in Alabama State Teachers As

sociation v. Alabama Public School and College Au

thority, 289 F.Sup. 784, aff’d mem. 393 U.S. 400.”

(2) . . the present case is the first and only

instance of which Appellants are aware in which a Fed

eral Court has enjoined the establishment, expansion or

escalation of a State-supported institution of higher

learning.”

(3) “. . . this case is the first and only instance of

which Appellants are aware in which a Federal Court

has transposed to the field of higher education the re

medial techniques applicable to public school desegrega

tion as justification for prohibiting the escalation of

State-supported college.”

(4) “. . . the majority decision of the Court below

enunciates a novel principle of constitutional law which

is not only without decision or support, but is squarely

in contravention of the ‘controlling principles’ approved

by this court in Alabama.’''

In the opinion of this Appellee, these contentions are with

out merit.

At the outset, Virginia State doubts whether Appellants’

second contention justifies plenary consideration of this case

by this busy Court, but respectfully calls attention to Lee

v. Macon County Board of Education, supra.

Appellants’ third contention is equally without merit in

that in enjoining the escalation of Bland, the lower court

clearly did not utilize the “remedial techniques applicable to

public school desegregation.”

Appellant’s first and fourth points are in essence the

same: they urge that the following language in Alabama

12

State Teachers’ Association v. Alabama Public School and

College Authority, supra gives them grounds to proceed:

“We conclude, therefore, that as long as the State and

a particular institution are dealing with admissions,

faculty and staff in good faith the basic requirement of

the affirmative duty to dismantle the dual system on the

college level, to the extent that the system may be based

upon racial considerations, is satisfied.” (Emphasis

added.) 289 F.Supp. at 789.

But Alabama is not authority for taking action in this

case on its facts.

In Alabama the plaintiffs, through a class action, sought

to prevent the construction and operation of a completely

new, four-year, degree-granting institution in Montgomery,

which institution was to be an extension of Auburn Uni

versity. At that time, Montgomery had four institutions

of higher learning, two private and two public. One of the

public institutions was Alabama State College which was

predominantly black. The other public institution was the

University of Alabama Montgomery Extension Center,

which was similar to a junior college. The Alabama Court

discussed the background of the case, particularly the con

cept of constructing and operating a new institution in

Montgomery. It found that a substantial and thorough in

vestigation had been made to determine the best means of

satisfying the higher educational needs within that area.

No such investigation is in the record, much less in the

Court’s decision in the instant case, that favors Bland be

coming a four-year college. All studies which were made and

meticulously cited in the lower Court’s opinion (App. “A”-

5) reached a diametrically opposite conclusion. For this

reason, if no other, Alabama is not authority for the posi

tion taken by the Board of Visitors of William and Mary in

13

Virginia and James M. Carson, President of Richard Bland

College. The Governor of Virginia and the State Council of

Higher Education, also represented by the Attorney Gen

eral of Virginia, did not join in the appeal. They could not.

They were already on record, based on the type of study

made in Alabama, as favoring a continuance of Bland as a

two-year college.

The Alabama Court further said:

“As plaintiffs themselves indicate ‘in terms of anything

heretofore existing in Montgomery, the Auburn branch

will be for all practical purposes a new institu tion”

(Emphasis added) 289 F. Supp, at 789.

Bland is not a new institution. For ten years it has been

virtually 100% white. The Virginia District Court found

not only this to be a fact but in addition found that the es

calation of Bland would thwart the tedious but successful

desegregation efforts by Virginia State College. In Ala

bama, the black college there involved (Alabama State) had

made no effort towards desegregation. The opposite is true

here. In Alabama, the white college (Auburn University)

recruited Negro faculty members successfully. Bland’s

faculty has been and was at the time of the decision below,

one hundred percent white. In the instant case, the Court

below found that if escalated Bland and Virginia State

“would offer substantially the same curricula.” (App. “A”-

5). In Alabama, the Court said:

“. . . evidence was introduced that tended to show that

Auburn would be more suitable for the purposes en

visioned because it could offer a wider range of courses,

greater breadth and depth of faculty, and greater

physical resources. It was also considered important by

the educator witnesses that Auburn had higher admis

sion and transfer requirements.” 289 F. Sup. at 789.

14

Nothing in this finding in Alabama applies to Bland. In

fact, the opposite is true.

Appellants would (in effect) substitute the word only for

basic in the language previously quoted on which they rely

{■op. cit. supra page 8). They contend that Bland’s “positive

program of actively recruiting Negro faculty and students”

(Jurisdictional Statement page 34)—which has increased

black enrollment from 0% to 1.6% and which has yet to

integrate the faculty—meets whatever else the affirmative

duty demands.

The Alabama court noted that the state is under an

affirmative duty to dismantle the dual system and to maxi

mize desegregation. “ [Djealing with admissions, faculty

and staff in good faith” is but one basic requirement of the

affirmative duty. The Alabama opinion does not support

the singularly restrictive interpretation of the affirmative

duty which Appellants would give it. The Court in Alabama

did not find as a fact that the creation of the new institution

would serve to perpetuate the dual system of education.

The Court in the instant case did find as a fact that the ex

pansion of Bland would perpetuate Virginia’s dual system

and would impede Virginia State’s efforts to desegregate.

The summary affirmance of Alabama by the Supreme

Court does not indicate approval of all that was said in

the opinion, much less Appellants’ interpretation of it.

Sanders v. Ellington, supra, in refusing to enjoin construc

tion of the University of Tennessee Nashville Center, em

phasized that its decision was based on its finding that the

construction would not perpetuate the dual system of higher

education. The Court there expressly stated that Alabama

did not control.

In summation, Appellants’ main thrust is that Alabama

controls. It does not. It is clearly distinguishable on its facts.

15

Appellants’ interpretation of the case is not tenable.3 Ala

bama needs no further review by the Supreme Court.

CONCLUSION

Like the Court below and the Court in Sanders, Virginia

State offers no comprehensive definition of what a state’s

affirmative duty requires. Virginia State respectfully sug

gests, however, that at the very least, such duty requires

an absence of active conduct which will, or is likely to,

hinder an institution’s active efforts to desegregate.

A state’s duty to dismantle its dual school system on the

college level prohibits one institution supported with tax

dollars from expanding existing facilities so as to per

petuate or aggravate an existing dual system. It further

prohibits one state supported college from directly or in

directly blocking the efforts of another state supported col

lege to comply with the law of the land and integrate its

faculty and students.

Virginia State is, of course, concerned with the fact that

Bland, as a two year college, is overwhelmingly white, and

that it will continue to be overwhelmingly white if escalated.

Paramount, however, is the interest of its Board of Visitors

in its own college, its own constitutionally-imposed affirma

tive duty to desegregate, and the threat that the proposed

escalation will forever relegate it to the status of a black

institution. The Board earnestly wishes to avoid a repeti

tion of the Old Dominion-Norfolk State College situation

3 The decision in Lee, supra, emerged, like Alabama, from the

Middle District of Alabama. In fact, the same judge who wrote the

opinion in Alabama appears to have been on the court which decided

Lee. Thus, Alabama Courts view a State’s affirmative duty to dis

mantle its dual system of higher education, not in the narrow view

presented on page 26 of Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement, but in

a view even more expansive than that asserted by the Virginia Court

in this case.

16

in which, as Appellant points out, a predominantly white

four-year institution exists practically side-by-side with a

predominantly black four-year institution. Two wrongs will

not make a right.

It is obvious that the questions on which the decision in

this cause depends are so unsubstantial as not to need

further argument. The findings of fact made by the Court

below are well supported by the record and not subject to

attack under the “clearly erroneous” standard. The relief

granted is neither unusual nor unprecedented. The Court

below merely enunciated a minimal requirement of the well

recognized duty of a state to dismantle its dual system of

higher education or at least not to take action which would

perpetuate it. The decision of the Court below is in line

with previous decisions.

This Appellee respectfully urges that this Honorable

Court dismiss this appeal or affirm the judgment of the

District Court without requiring briefs or further argu

ment.

Respectfully submitted,

T h e B oard of V isito rs of

V ir g in ia S ta te College

E dward S. H ir sc h l e r

E verette G. A l l e n , J r .

Massey Building

Fourth & Main Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Counsel for The Board of Visitors

of Virginia State College

17

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Edward S. Hirschler, a member of the bar of the

Supreme Court of the United States and counsel for the

Board of Visitors of the Virginia State College, hereby

certify that copies of the within Motion of Appellee to

Dismiss Appeal or Affirm Judgment were served upon

counsel of record for all parties herein by depositing the

same in the United States Post Office, with first class

postage prepaid, to their respective addresses of record as

follows: to R. D. Mcllwaine, III, P.O. Box 705, Peters

burg, Virginia 23803, Special Counsel for The Board of

Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia

and James M. Carson, President of Richard Bland College;

S. W. Tucker, Henry L. Marsh, III, Seymour Dubow and

James L. Benton, Jr., 214 East Clay Street, Richmond, Vir

ginia 23219, and Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III and

Norman Chachkin, 10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030, New

York, New York 10019, counsel for plaintiffs; to Andrew

P. Miller, William G. Broaddus and D. Patrick Lacy, Jr.,

Supreme Court Building, Richmond, Virginia 23219, coun

sel for A. Linwood Holton, Governor of Virginia, the

State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, the Board

of Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia,

and James M. Carson, President of Richard Bland College;

and to Philip J. Hirschkop and Richard E. Croach, P.O.

Box 234, Alexandria, Virginia 22314, counsel for Amicus

Curiae, American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia; this

3rd day of September, 1971. All parties required to be

served have been served.

E dward S. H ir sc h ler

Counsel for The Board of Visitors

of Virginia State College