Singleton v Vance County BOE Motion and Rehearing Petition

Public Court Documents

March 18, 1974

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Singleton v Vance County BOE Motion and Rehearing Petition, 1974. c976f984-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93a034ef-ac1b-4ef9-a3d1-5534d7b220f6/singleton-v-vance-county-boe-motion-and-rehearing-petition. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

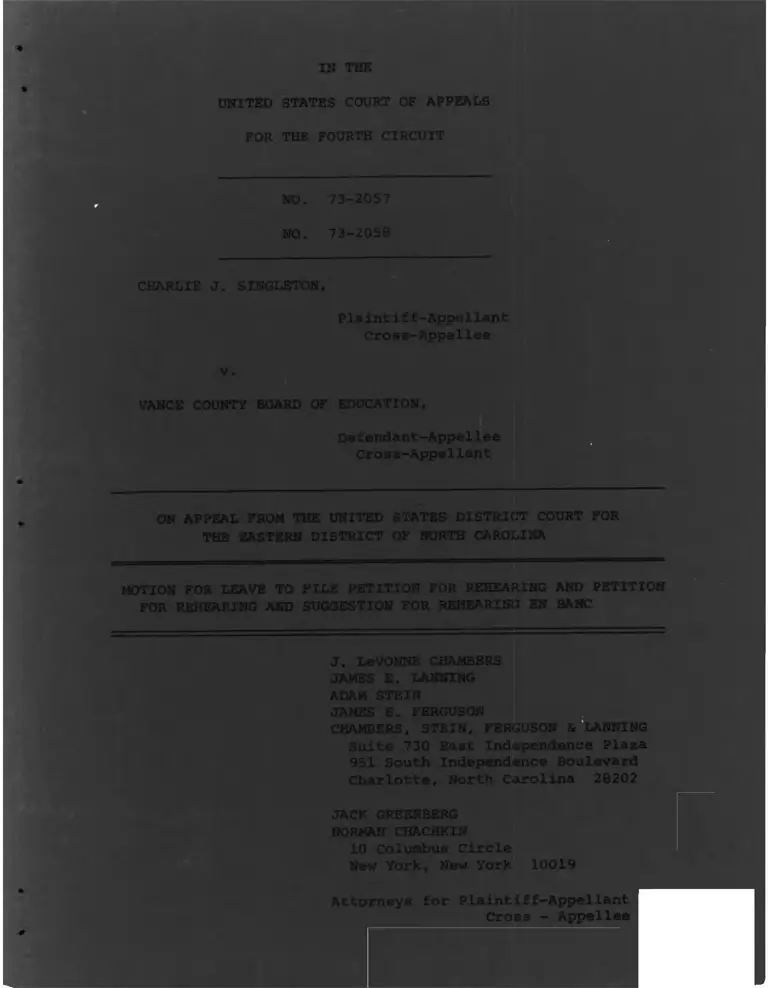

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-2057

NO. 73-2058

CHARLIE J. SINGLETON,

Plaintiff-Appellant

Cross-Appellee

v.

VANCE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendant-Appe11ee

Cross-Appellant

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR REHEARING AND PETITION

FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E. BANNING

ADAM STEIN

JAMES E. FERGUSON

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & LANNING

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Cross - Appellee

J u l iu s L eV o n n e C h a m b e r s

A d a m St e in

J a m e s E. F e r o u b o n , II

J a m e s E. L a n n in o

Ro b e r t B e lt o n

C H A R L E 3 L . B EC TO N

F red A . H ic k s

M e l v in L . W att

J o n a t h a n W a l l a s

K a r l A d k in s

J a m e s C . F u l l e r , J r .

C H A M B E R S , STEIN . F E R G U S O N & L A N N IN G

A tto r n eys a t La w

S u it e 7 3 0 E a s t I n d e p e n d e n c e P laza

In d e p e n d e n c e B o u l e v a r d a t M c D o w e l l S tr eet

C H A R L O T T E , N O R T H C A R O L I N A 28202

T e l e p h o n e ( 7 0 4 ) 3 7 5 - 6 4 6 1

May 23, 1974

1 3 7 Ea s t R o s e m a r y S tre e t

C h a p e l H i l l . N o r t h C a r o l i n a 2 7 5 1 4

T e l e p h o n e ( 9 1 9 ) 9 6 7 - 7 0 6 6

I n C h a p e l H il l

A d a m S t e in

C h a r le s L . B ec to n

Honorable William K. Slate, II

Clerk, United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

Tenth & Main Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Re: Singleton v. Vance County

Board of Education Nos.

73-2057 and 73-2058

Dear Mr. Slate:

Enclosed are the original and twenty-four copies of Cross-

Appellee's Motion for Leave to File Petition for Rehearing

and Petition for Rehearing and suggestion for Rehearing En

Banc to be filed in connection with the above matter.

By copy of this letter, I am serving a copy of same upon

counsel for the defendant.

Sincerely yours,

LbVonne Chambers

JLC:j ch

Enclosures

cc: Mr. George

Norman

T. Blackburn-w/enc.

Chachkin-w/enc.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-2057

No. 73-2058

CHARLIE J. SINGLETON,

Plaintiff - Appellant

Cross - Appellee

v.

VANCE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendant - Appellee

Cross - Appellant

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR REHEARING

AND PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESION

FOR A REHEARING EN BANC

Plaintiff-Appellant-Cross-Appellee respectfully moves the

court for leave to file a petition for rehearing and suggestion

for rehearing en banc out of term and respectfully petitions the

court for a rehearing in this matter eii banc. In support of his

motion and petition, the appellant respectfully shows the court

the following:

1. On May 8, 1974 a panel entered a per curiam decision re

manding this case to the district court, holding that the Vance

County Board of Education is not a "person" subject to juris

diction under 42 U.S.C. §1983. Since this proceeding had been

brought under Section 1983 and 28 U.S.C. §1343 (3) and (4), the

court stated that "a serious jurisdictional question" required

that the case be remanded to the district court. City of Kenosha.

v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973). The plaintiff was granted leave

to amend his jurisdictional allegation in the district court and

the district court was to consider further the jurisdictional

question. Plaintiff's counsel were unable to complete a petition

for rehearing because of their involvement in pending cases and

because of their efforts to review the effect of the Supreme

Court's decision in City of Kenosha and subsequent cases on

pending actions for desegregation of schools and challenges

against the dismissals of teachers and school personnel because

of race. We respectfully submit that it would expedite dis

position of this case and would save the court and parties

substantial time should the court grant leave to make juris

dictional amendments here as permitted by 28 U.S.C. §1653.

Additionally, this court did not note the additional juris

dictional allegations of 42 U.S.C. §1981 which would sustain

the jurisdiction of the court irrespective of whether the Board

of Education is a person within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. §1983.

2 . Jurisdiction can be likewise sustained under 28 U.S.C.

§1331. The plaintiff respectfully prays that the court grant

leave to amend the jurisdictional allegation to show juris

diction of the court under 28 U.S.C. §1331, City of Kenosha v.

Bruno, supra., 37 L.ed.2d at 117 and the Thirteenth and Fourth-

eenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States and

28 U.S.C. §1343 (3), Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403

U.S. 388 (1971). Should the court permit the jurisdictional

amendment as requested and further briefing of the issue it

would save substantial time for the court and the parties and

would allow prompt disposition of the proceeding.

3. Leave to suspend the time requirement for petitioning

for rehearing is authorized under Rules 2 and 26 of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure.

STATEMENT

This appeal involves the dismissal of a black teacher

by the Vance County Board of Education. The district court

found that the teacher was dismissed in violation of rights

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment and that the teacher was

entitled to injunctive relief and loss of earnings and expenses.

The plaintiff appealed the portion of the district court order

denying an award of lost earnings for the two years that the

plaintiff was unable to obtain employment. The defendant

appealed challenging the finding that the plaintiff had been

deprived of rights secured by the Constitution and the award

of loss of earnings and counsel fees. All issues have been

properly briefed and the matter is ripe for final disposition.

-4-

ARGUMENT I

Plaintiff properly alleges jurisdiction under 42 U.S.C.

§1981. In the complaint filed in this action the plaintiff

alleged jurisdiction of the court under 42 U.S.C. §1981 as well

as §1983. Even if it is concluded that the Board is not a

person within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. §1983 no similar

problem is presented under 42 U.S.C. §1981. EEOC v. Liberty

Mutual, 480 F.2d 69 (5th Cir. 1973); Brown v. Gaston County

Dyeing Machine Company, 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972); Sanders

v. Dobbs House, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970); Penn y .

Schlesinger, 6 E.P.D. 119041 (5 th Cir. 197 3) ; Henderson v.

Defense Contact Administration Services Regent, ___F.Supp.___,

7 E.P.D. 119058 (S.D.N.Y. 1974).

ARGUMENT II

This court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1653 to permit

amendments of jurisdictional allegations.

In order to expedite disposition of this matter the court

should permit the plaintiff to amend his jurisdictional alle

gation to correct any jurisdictional defect. This court has

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1653 to permit such amendments.

Willingham v. Morgan, 395 U.S. 402 (1969); Eklurid v. Mora,

410 F.2d 731 (5th Cir. 1969). The plaintiff respectfully prays

leave of the court to amend his complaint to set forth juris

diction under 28 U.S.C. §1331 and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. The

plaintiff desires to amend his complaint as follows:

17 But see attached opinions.

Jurisdiction of the court is invoked

pursuant to Title 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and

28 U.S.C. §1331, this being a suit in

equity authorized by law under 42 U.S.C.

§1981 and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States to redress the deprivation

of federally protected rights, privileges

and ammunities. The rights, privileges

and ammunities sought to be redressed

herein are those secured by the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States and 42 U.S.C. §1981.

This is also an action arising under the

Constitution and laws of the United States

and involving matters in controversy in

excess of $10,000.00, exclusive of interest

and costs. The constitutional and statutory

provisions involved are the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States and 42 U.S.C. §1981.

The plaintiff seeks injunctive relief for

the deprivation of the constitutionally

protected rights and the loss in earnings

of $9,777.10 for two years plus counsel

fees which exceed $10,000.00, exclusive

-6-

of interest and costs.

The facts in this matter, including the actual fees and

expenses sustained by the plaintiff have already been determined

by the district court and can easily be reviewed here. The

amendment requested, we submit, would eliminate any problem

of jurisdiction and would allow for final disposition of this

matter on appeal. City of Kenosha v. Bruno, supra; Bivens v.

Six Unknown Named Agents, supra.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the plaintiff respectfully prays

that the court grant him leave to file a petition for rehearing

in this matter; that the court grant the petition for rehearing

en banc; that the court permit the amendment to the jurisdictional

allegation as prayed for; that the court permit the parties

to file supplemental briefs with respect to the jurisdictional

issues; that the court sustain jurisdiction to dispose of this

matter and grant the relief as prayed for by the plaintiff on

appeal.

ADAM STEIN

JAMES E. FERGUSON

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Lanning

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Cross-Appellee

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that he has this

day served a copy of the foregoing Motion for Leave upon

counsel for the defendant by depositing a copy of same in

the United States mail, postage prepaid, addressed to:

George T. Blackburn

Perry, Kittrell, Blackburn & Blackburn

109 Young Street

Henderson, North Carolina 27536

This the 23rd day of May, 1974.

a i n t if f - App e IXSTI t

Cross-Appellee

3n tfjc

TfOf tfje Cl'i'CUtt

September T erm, 1973 September Session, 1973

No. 73-10S5

A vrora E ducation A ssociation

E ast, E t Al .(

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

B oard Or E ducation Or A urora

P ublic S chool D istrict N o. 131

Or Ivane County, Illinois,

E t A l .,

' Dcf cndants-Appellees.^

A }) p e a 1 from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Northern District

of Illinois,-Eastern

- Division

72 C 414

W illiam J. L ynch ,

Judge.

H eard October 17, 1973 — Decided December 20, 1973

Before S w y g e r t , Chief Judge, C u m m i n g s , Circuit Judge,

and W yzanski*, Senior District Judge.

W yzanski, Senior District Judge. Seven public school

teachers in Aurora, Kane County, Illinois and the Aurora

Education Association East, of which they are members,

arc plaintiffs. The Board of Education of Aurora Public

School District No. 131 of Kane County, the members of

that Board, and the Superintendent of Aurora’s school

system are defendants.

June 9, 1971, during collective bargaining and wage dis

putes between the teachers represented by the Association

_______ v

* Senior District Judge Charles Edward V/yzanski’, Jr., o£ the District

pi Massachusetts, is sitting by designation, .

73-10S5 2

and the Board, the Association at one of its meetings

adopted this resolution:

“ Be- it resolved that the teachers of District #131

will not return to the classroom in the fall if there is

at [that] time no satisfactory settlement of the con

tract between the Board of Education and the AEAE

and further that an. open meeting be held on Septem

ber 2 for all teachers to assess the position of the

AEAE at that time.”

Thereupon the Board, dropping its negotiations for a

collective bargain with the Association, wrote to each

teacher a letter offering him or her an individual contract

for the 1971-1972 school year. Each proposed contract

provided that the contracting teacher expressly agreed

that

“ (1) By urging, advocating, recommending, and as

serting the right to strike by its members prior to

the vote, and at the meeting held on Jvnm 9, 1971, the

AEAE no longer qualifies as the organization that,

under the established School Board Policy (1.30 Arti

cle II) [is] a bargaining representative of the teach

ers of the school system, and accordingly will not be

recognized by the School Board as such agent for the

teachers.

“ Nothing in this paragraph is intended to prevent

the Teacher from belonging to the AEAE, but relates

only to AEAE’s lack of qualification to act as the

bargaining agent for the Teacher in negotiations with

the School Board.”

In the foregoing, the citation of School Board Policy

1.30 Article II is a reference to a provision permitting a

labor organization to negotiate, on behalf of teachers, with

the Board, but excluding from all bargaining rights "any

organization (1) which asserts the right to strike against

any . . . agency of the government, or to assist or to par

ticipate in any such. strike, or which imposes a duty or

obligation to conduct, assist or participate in any_ such

strike. . . This emphasized exclusory language is the

focal point on which this case at bar turns.

Many teachers executed the proposed contract, and thus

became entitled to advantages not offered in the 1970-1971

3 73-1085

contracts. To the seven individual plaintiffs, none of whom

executed the preferred contracts, the Board offered con

tinued employment for the new year on the old terms.

Favic dc mieux, the seven continued at work under the

disadvantageous ].070-1971 terms, and then brought this

suit in the District Court.

Belying on the United States Constitution’s Fourteenth

Amendment’s due process clause and its alleged incorpo

ration of the principles of the First Amendment, and also

invoking Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42

U.S.C. $'1983, plaintiffs sought (1) a declaration that, as

here applied, School Board Policy 1.30 was invalid, and

that plaintiff teachers were entitled to be placed on the

same salary schedule and like terms as those teachers who

had executed the proposed 1971-1972 contract, (2) an

injunction protecting for the future the rights so declared,

(3) back pay based on the 1971-1972 schedule, (4) $25,000

actual damages, (5) $25,000 exemplary damages, and (G)

an attorney’s fees and costs.

Defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on the

grounds that (1) the complaint failed to state a valid

claim, (2) plaintiffs’ purported claims -under 42 U.S.C.

$1983 did not lie against the Board or its members, and

(3) the Association was not a proper plaintiff to assert

the alleged claim under 42 U.S.C. $19S3.

On the ground that it failed to slate a valid claim, the

District Court dismissed the complaint. Relying upon

Hanover Township Federation of Teachers v. Hanover

Community School C o r p 457 F.2d 456 (7th Cir. 1972),

the Court’s opinion held that the Board’s proposed con

tracts for 1971-1972 and the Board’s refusal to continue

collective bargaining with the. Association had not violated

42 U.S.C. $1983 or plaintiffs’ claimed rights under the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Plaintiffs appeal from the District Court’s dismissal of

their complaint.

IVc address ourselves to the already quoted exclusory

provision in School Board Policy 1.30.

National Ass’n. of Letter Carriers v. Blount, 305 F.Supp.

54G (D.D.C. 1969), appeal dismissed by stipulation, 400

73-1085 4

U.S. 801 (1970) and United Federation of Postal Clerics

v. Blount, 325 F.Supp. S79 (D.D.C.), aff’ul mem. as to

issues not here involved, 404 U.S. 802 (1971), invalidated

virtually identical provisions in a federal statute and a

federal administrative provision. The cited cases pointed

out that the language is ambiguous, leaving it unclear

whether it encompasses the mere philosophical or political

assertion of the declarant’s belief that he Itas a right to

strike. A governmental inhibition against the declaration

of such a purely theoretical position" is a plain case of an

unconstitutional official interference with freedom of speech

and is unconstitutional. Ycifes v. United States, 354 U.S.

293 (1957). "Where a governmental body seeks by an over

broad regulation to preclude both lawful and unlawful

speech, the regulation because of its overbreadth is a vio

lation of guarantees of free speech and is unconstitutional.

Keyishan v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 5S9 (1967).

We wholly agree with the analysis of the three-judge

district courts in the. opinions already mentioned. The

Board’s Policy 1.30 as here applied precludes a teacher

from receiving a full salary and perquisites if, as a mere

matter of dogma, he holds to the belief that teachers

should be free to strike against governmental agencies.

Such throttling of freedom of belief and of speech is con

trary to that part of the First Amendment which is incor

porated in Hie Fourteenth Amendment. "We need no recital

of literary authorities from John Milton to Harold J.

Laski or of judicial luminaries from Justices Holmes,

Brandcis, and Cnrdozo to Black, Frankfurter, and llarlan

(to mention only the dead) to buttress the principle that

the teacher, like any other citizen, is free to think as he

likes, and to express those views academically provided

action is not advocated but merely adumbrated. 42 U.S.C.

$!9S3 gives a person protection against interference by

state officials with that fundamental civil liberty.

Since the Board’s Policy 1.30 seeks, inter alia, to pro

hibit constitutionally permissible free speech, it is because

of its overbreadth, violative of the due process clause of

the. Fourteenth Amendment. Keyishan v. Board of Regents,

supra.

Defendants and the District Court misconceive Hanover

Township Federation of Teachers v. Hanover Community

73-1085

School Corp., 457 F.2d 45G (7th Cir. 1972). Whatever else

may he said about that case, it dealt with the question

whether a public body is under a constitutional duty, apart

from statute, to bargain collectively with the labor repre

sentative of its employees. There was no occasion to con

sider in that court, and the court did not consider, the

problem of this case, that is. whether a public body may

interfere with its employees’ freedoms to think and to

speak—which from the beginning of time have been recog

nized as wholly different from the freedom to associate

and to seek to use the strength which comes from union

in assembly and action. Sec Wvzanski, “ The Open Win

dow and the Open Door,” 35 Cal. L. Rev. 336 (1947).

Defendants suggest miscellaneous grounds, not relied

upon by the District Court, which they argue could have

supported its dismissal of the complaint.

We note that at least one of the points pressed by defen

dants is unsound. The Hoard is not a municipal corpo

ration and in that capacity frontside the coverage of 42

U.S.C. ^1933, as construed in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

167 (1961).

There arc other points, such as whether plaintiffs could

recover the types of damage they claim, which do not go

to the only issue before this court: that is, whether the

complaint states a valid cause of action. Wc shall leave

such points without comment until, if ever, they become

the basis of a judgment entered by the District Court.

It is not our function to issue the sort of declaratory .judg

ment which would tell a District Judge how he should

decide a hypothetical case which may or may not ulti

mately be supported by properly presented evidence and

which may or may not be pressed to a conclusion by the

litigants before that judge.

After the case was argued before us. and in accordance

with discussions at our bar, the parties sought to settle

this case. But no agreement was reached. Instead, uni

laterally, defendants revised Subsection (1) of Article 11

of School Board Policy 1.30 to eliminate the language

“ asserts the right to strike against any local, state or

federal agency of the government.” This unilateral action

is not the equivalent of a promise made to an adversary

73-10S5 6

as part_ of a settlement. Nor is it a stipulation made in

court binding the declarant forever to adhere to a new

policy based on a public confession of earlier unconstitu

tional action. Nor does it offer financial recompense to

those plaintiffs who may have suffered damage caused by

defendant’s unlawful acts. Under these circumstances,

plaintiffs have not lost their standing to invoke at least

equitable relief, Ilccht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944),

not to mention the continued vitality of their claim for

monetary compensation, remedial and punitive.

The judgment of the District Court, dismissing the

complaint, is reversed.

A true Copy:

Teste:

Clerk of the United Stales Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

USCA <1013—Tho Schcfler Press, Inc., Chicago, Illinois—12-20- 73—200

IN TH3 UNITED GTATE3 DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT CP VYC.'UNG

-o-

HARBARA COURTNEY, )Plaintiff, )

vs. )

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, LINCOLN j

COUNTY, WYOMING, and ORSON NAT 12, )

DSLAIN3 ROBERTS, "AY ROBINSON, )

DR. L-AVID KCMINBXY, DR. GERALD ) Do. 5900 Civil

DAVIS, JON DERC.MEDIS, DEED ERICK-

SON, GEROLD NORRIS and LOYD SIMP

SON, individually and in their of

ficial caoacities, and ROBERT G.

NAYLOR, ARLYN WAINWRIGHT and

WILLIAM L. MONEY, individually,

and in their official capacities,

Defendants.

Charles E. Graves and Urbigkit, Moriarity and Halle of

Cheyenne, Wyoming, appearing as attorneys for plaintiff.

E. J. Herschler, Kemr.erer. Wyoming, and Hirst, Applegate

and Dray, Cheyenne, Wyoming, appearing as attorneys for defend

ants.

Judge 1s Memorandum

KERR, Judge.

Decided February 28, 1974.

The above matter is an action brought by plaintiff alleg

ing termination of her employment as a school teacher by the

defendant school district in a wrongful manner and in violation

of her civil rights. Defendants, in their individual and of

ficial capacities, have filed motions for "dismissal or for

summary Judgment". The school board, in it3 official status,

has raised the defenses that (1 ) it is not a "person" as defined

under the Civil Rights Act, 4? U.S.C. 5 1983; and (2) that the

doctrine of respondeat superior docs not apply to such an ac

tion. The defendants, in their individual capacities, have moved

for "dismissal or for summary Judgment" on the grounds (1) that

no claim for which relief can be granted has been stated by the

plaintiff; (2) that the statute of limitations, Wyo. Stat.

§ 1-19 (1957), bars this action; and (3) that all actions taken

or done by the defendants were performed in good faith. These

1.

notions have been filed without supporting affidavits or doc

uments. Plaintiff has not filed any documents opposing the

notions.

Plaintiff was hired as an elementary school teacher by the

defendants for the 3chool year 1570-71. Her contract was renew

ed for 1971-72. The board did net renew her contract for the

school year 1972-73 because of conditions it considered detri

mental to her teaching duties. Plaintiff is divorced and the

mother of two minor children. Hals situation ha3 caused finan

cial problems and these problems were the basis for the board's

non-renewal. In a letter to plaintiff written by the super

intendent of 3Chool3, it was stated that plaintiff's non-payment

of bills and the writing of insufficient funds checks were the

reasons the board Intended not to renew her contract. On this

point the defendant alleges that plaintiff in fact resigned,

and therefore, there was technically never any non-renewal on

its part. Plaintiff denies that her personal financial prob

lems have affected her classroom performance. In addition,

plaintiff alleges that a State Department of Education form,

completed by one of the defendants, Arlyn Wainwright, contained

false, slanderous and libelous material; and that the defend

ants, in whole or in part, have conspired to h a m her reputa

tion and good name and to prevent her from obtaining other em

ployment. Defendants deny that the evaluation was malicious or

libelous, but was rather a true and correct evaluation of

plaintiff.

Plaintiff, with leave of Court and consent of the defendants,

has filed an amended complaint. Defendants have not filed their

amended answer to the amended complaint. The Court in viewing

the pleadings must construe them so as to do substantial justice,

Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(f), disregarding all non-prejudicial error.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 6l. By relation back, and for purposes of thi3

opinion, the Court assumes that defendants would adopt their

original answer substantially as filed.

The Board in its official capacity has moved for dismissal

on the grounds it is not a person within the meaning of 42

U.S.C. § 1533, and that the doctrine of respondeat superior docs

not apply to such a cause of action, so that as to it no claim

is stated for which relief may be granted. Treating all motions

filed by the defendants as notions to dismiss, it is clear that

the Court must "[Cjonstrue all well-pleaded, material allegations

in the complaint as being true and admitted for purposes of the

notion, unless clearly unwarranted. Only when it appears to a

certainty that no basi3 for relief is present under the stated

facts to support the claim nay the Court dismiss due to the in

sufficiency of the claim". Ga3-A-Car, Inc. v. American Petro-

fina, Inc., 484 P.?d 1102 (10th Cir. 1973); 2 A. Moore Federal

Practice § 12.03 (2d ed. 1968). "A case brought under the Civil

Rights Act should not be dismissed at the pleading stage unless

It appears to a certainty that the plaintiff would be entitled

to no relief under any state of facts which could be proved in

support of his claim". Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School

District, 427 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970); cf. Hudson v. Harris,

1178 F.2d 244 (10th Cir. 1973). With these guidelines in mind,

the Court considers the various grounds raised.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 states, in part, "Every person who, under

color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage,

of any State . . . subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen . . . to the deprivation of any rights . . . , shall be

liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity,

or other proceeding . . .". The basic requirements of a com

plaint based upon 42 U.S.C. 5 1933 are: "(1) that the conduct

complained of was engaged under color of the stato law, and (2)

that such conduct deprived the plaintiff of rights, privileges,

or immunities secured by the Federal Constitution and laws".

Jones v. Hopper, 4i0 F.2d 1323 (10th Cir. 1969). Defendants

arguo, based on Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961), that they

arc not a "person" within the meaning of the statute, as that

3-

case held that "municipal corporations" are not within the ambit

of 5 1933. Under Wyoming law, school districts are cra-nted cor

porate status. Wyo• Stat., 21.1-17 (1273)* Dy law, such dis

tricts "[M ]ay sue and he sued in the nano by which the dljtrict

is designated". Wyo. Stat. § 21.1-77(a) (1973). This suscep

tibility to suit ha3 been recognised by the Wyoming Supreme Court.

See 0 'Mella v. Sweetwater County School District, 457 P.2d 540

(1972); Monohan v. Doard of Trustees, 486 P.2d 235 (1971).

Their status is one of a public corporation or quasi-corporation.

See People cue rel Younger v. County of 21 Dorado, 487 P.2d 1103,

1199 (1971). An action brought under 42 U.S.C. 5 1933 is to be

liberally viewed so as to effectuate the rights guaranteed there

by. Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 54-7 (19^7)• A school district is

corporate in nature, and distinct from a municipal corporation

under Wyoming law. Under the new Education Code, Wyo. Stat.

§ 21.1-17 et; seq., school districts have been granted many new

and sweeping powers and are even allowed to provide through in

surance coverage for any school board member or district employee

against whom judgment may be had. These powers are a dramatic

change from the old law, v/hereunder school boards only had the

power to sell district property. See Wyo. Stat. § 21-115(7)

(1957) (repealed 19o9). These new powers evidence the clear in

tention of making school districts more than simply an agent of

the state, a3 is a municipal corporation. It has been held,

"[P]or purposes of 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the board i3 a 'person'

. . . ". See Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District,

above at 323; contra Harvey v. Sadler, 331 F.2d 387 (9th Cir.

IS0 9).

From the above, it is the opinion of thi3 Court that, for

purposes of this law, a school board is a ''person" and subject

to suit. As for the board members individually, it is clear that

Monroe v. Pape, above, is no bar to such an action for damages.

See also City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973), v.’hereir.

the Court held that injunctive relief against a municipal officer

4.

may be hud, but not ns against the municipality. See Smith v.

Losce, ‘ l o j P.2d 33!; (10th Cir. 1973).

Tiie Board asserts that the acts of the superintendent and

principal cannot be imputed to it, so as to make it vicariously

liable for such actions. Defendants cite various cases, in

cluding Salazar v. Dowd, 255 F.Supp. 220 (D.Colo. 1956), as

support for their position. In Dewell v. Lawson, Ho. 73-1157

(10th Cir. filed January 7, 197’;), wherein plaintiff had 3ued

Oklahoma City and the Chief of Police and the lower court had

dismissed the action as against the Chief of Police, the Court,

Circuit Judge Barrett, in reversing stated, "The common law de

fense under state law would not be available to a state officer

charged in a Federal Civil Rights cause of action. Thus the

doctrine of respondeat superior cognizable under Oklahoma law

is not a defense available to Chief Lawson in this federal cause

of action. Our holding in this respect rejected (sic) the op

posite holdings of . . ., Salazar v. Dowd, . . . and other like

decisions".

From the foregoing it follows that the doctrine of re

spondeat superior is not a bar to this action, and the board be

may/vicarlously liable for the actions of its agents.

The board members, individually, have asserted that the

action is barred as their actions were taken in good faith.

Be that as it may, it is clear that good faith is not an abso

lute bar to this action, but only a defense to be proven by the

board at trial. See Smith v. Losee and Dowell v, Lawson, supra.

Cnee plaintiff has proven a prlma facie case, it will be the bur

den of the defendants to prove good faith or other justification

for their actions. See Martin v. Duffle, i;63 F.2d h o k (10th

Cir. 1972). In this respect, it is clear that a claim for which

relief might be granted has been stated a3 against the board,

its individual members and agents.

Two cf the defendants, the principal and the superintendent

of the district, have raised the defense of the statute of lin-

5.

ltatior.3 on the theory that, as against then, this is an action

for slander and libel. They argue that such an action is bar

red by Wyo. Stat. § 1-ig (1957) which provides that such ac

tions be brought within one year. Fron the complaint and the

amended complaint, such a conclusion is not easily reached. To

the contrary, it is clear that the actions of these defendants

are intertwined with those of their co-defendants to an inex

plicable degree. This is an instance where, due to the actions

of these defendants, the "reputation, honor, integrity or good

name" of plaintiff may be at stake. Board of Regents v. Roth,

^08 U.S. 56'l (1971). In these circumstances, the claim for re

lief should not be dismissed unless it appeai'3 beyond all doubt

that plaintiff can prove no set of facts supporting the claim

for relief. See Hudson v. Harris, 7̂8 F.2d 2^U (10th Cir.

1973).

For the reasons stated, the motions for "summary judgment

or for dismissal" should be overruled.

6.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

OCALA DIVISION

ROBERT BAIRD, Plaintiff,

NO. 74-1-Civ-Oc

JOE STRICKLAND, individually, and

as Superintendent of the Sumter

County Public School System; THE

SCHOOL BOARD OF SUMTER COUNTY,

FLORIDA, ERWIN BRYAN, JR., JOHN W.

WALLACE, C. AUBREY CARUTHERS, JOE

D. MERRITT and SHERMAN G. WILSON,

individually, and as members of

the School Board of Sumter County,

Florida,

R E C E I V E D

MAR 2574

f>cA Ci7iC£ CF

GINERAL C0U,NS;L

Defendants.

ORDER AND INJUNCTION

This is an action by a high school teacher alleging that

his dismissal from employment by the school board of Sumter County,

Florida, for his personal conduct at two school functions violated

his rights secured by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution. He seeks reinstatement, back pay and

attorney’s fees. Jurisdiction is premised on 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331,

1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. § 1903.

Plaintiff claims the Florida statute under which he was

dismissed is void for vagueness, and further claims he was denied

due process of lav/ when he did not receive a hearing before a fair

and impartial tribunal. The Court need not reach the question of

whether Florida Statutes §231.36(6) is void for vagueness because

of the disposition made of plaintiff's other claim for relief.

On November 3, 1973 , Joseph D. Merritt, a member of the

Sumter County School Board, telephoned Joseph R. Strickland, Super

intendent of Schools, Sumter County, Florida, to report that he had

RECEIVED

M. a R 2 0 1974

• • t mV OFf ICE CF

been told by certain adults who were in attendance at a school foot

ball game and subsequent school dance the previous evening that they

had heard plaintiff make obscene statements in the presence of others

On November 5, 1973, plaintiff was suspended from the classroom with

pay by the superintendent, pursuant to Florida Statutes § 230. 33(7) (h)

The next day defendants met as the school board and suspended plain

tiff with pay, pursuant to the provisions of Florida Statutes

§ 230.23 (5) (g), until charges relating to his conduct of November 5th

could be prepared. Joseph Merritt participated in this school board

hearing and voted to suspend plaintiff.

On November 20, 1973, after formal charges had been served

on plaintiff, the school board voted to suspend him without pay until

a formal hearing could be held on December 5, 1973. Joseph Merritt

attended and participated in this November 20th meeting, and cast his

vote in favor of suspending plaintiff without pay. At the December

5th school board hearing the board heard and ruled on plaintiff's

motions (1) to dismiss the charges as violating plaintiff's First

Amendment rights, (2) to dismiss the charges for insufficiency of

notice, and (3) for discovery. Joseph Merritt attended and partici

pated in this meeting and voted on plaintiff's motions.

On December 17, 1973, the school board, after hearing,

voted to dismiss the plaintiff from employment. Joseph Merritt, at

the urging of counsel for plaintiff, disqualified himself from par

ticipating in this hearing and from voting on the dismissal. Counsel

for plaintiff had previously filed a motion for disqualification of

the entire school board and had requested the appointment of a hear

ing examiner, pursuant to Florida Statutes § 120.09(1), to hear

plaintiff's case. These requests were denied.

Prior to the commencement of the December 17th hearing,

and before public determination to terminate plaintiff had been

-2 -

reached, plaintiff was paid all earned wages and benefits.

Plaintiff contends (1) that although Merritt disqualifieu-

himself from participating in the December 17th meeting at which

plaintiff was dismissed, he should have done so before participating

in the meetings of November 6th, November 20th and December 5, 1973,

(2) that Merritt's participation in these three earlier meetings

tainted the appearance of impartiality of the other defendants who

composed the remainder of the school board, and they all should have

disqualified themselves from hearing plaintiff's case, (3) that the

defendants had prejudged plaintiff’s case in advance of the December

17th public hearing, and (4) that plaintiff was, therefore, denied

a fair hearing before an unprejudiced and unbiased tribunal.

It is plaintiff's specific contention that, since Merritt

was the person who made the first complaint of plaintiff's action,

he might be called as a witness at plaintiff's hearing and that he

had firsthand information on the evolution of the case in advance of

the hearing. Plaintiff claims Merritt's firsthand knowledge,

coupled with his participation in the three earlier school board

hearings involving plaintiff, acted to destroy the appearance of im

partiality of the entire tribunal in derogation of his rights to a

fair hearing guaranteed by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Furthermore, he claims to have been denied a fair hear

ing by the defendants' paying his wages and benefits before he was

granted a public hearing and dismissed. This action is alleged to

have indicated a predisposition on the part of the defendants as

members of the school board to dismiss plaintiff from further employ

ment before he was afforded an opportunity to present his case at

the public hearing.

Tne Court holds that Merritt should have disqualified him

self from any participation in plaintiff's case because his personal

-3-

involvement in filing the complaint against plaintiff, coupled with

his participation in the three earlier school board meetings, gave .

the appearance of depriving plaintiff of a fair hearing before an

unbiased tribunal.

Rudin-.ental due process in school administrative proceed

ings is guaranteed in cases involving the suspension of students,

Dixon v. Alabama State Bd. of Ed., 294 F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961),

and in cases involving termination of school teachers. Ferguson v.

Thomas, 430 F. 2d 852 (5th Cir. 1970). In Ferguson the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit said.

Within the matrix of the particular circumstances

present when a teacher who is to be terminated

for cause opposes his termination, minimum pro

cedural due process requires that:

(a) ....

(b) . . . .

(c) [the teacher be provided a hearing]

(d) that hearing should be before a tribu-

• nal that....has an apparent impartiality toward

_ the charges. (Note the dictum in Pickering v.

Board of Education, 391 U. S. 563, 88 S. Ct. 1731,

20 L. Ed. 2d 811 (1968) at 391 U. S. 578, n. 2,

88 S. Ct. 1731).

430 F. 2d 852 at 856.

The requirement of impartiality of a tribunal sitting to

determine whether or not to dismiss or penalize school teachers for

alleged wrongs lias been recognized by the courts of the State of

Florida. State ex rel. Allen v. Board of Public Instruction. 214

So. 2d 7 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1968). Furthermore, the fact that the

impartiality of less than a majority of the tribunal is challenged

does not change the requirements of disqualification. State ex rel.

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction, supra, cf. Esteban _v. Central

Missouri Stare College, 277 F. Supp. 649 (W.D. Mo. 1967).

Whether or not Merrittwas actually biased in his partici

pation in the three earlier meetings of the school board, and the

Court is disposed to believe that he was not, and whether or not

Merritt's participation therein acted to taint the impartiality of

the other defendants, a quasi-judicial body has a strict duty to

avoid even the appearance of impropriety and partiality. 1erguscn

v. Thomas, -130 F. 2d 052,. 056 (5th Cir. 1970). Therefore, Merritt

had a duty to disqualify himself from participation in any school

board meetings involving plaintiff's case. Furthermore, once Merritt

participated in those three earlier meetings the other defendants had

a duty to disqualify themselves from judging plaintiff's case.

The Court further holds that the action of defendants in

paying plaintiff his accrued wages and benefits before the December

17th school board meeting, at which he was afforded a hearing and

dismissed, indicates they had prejudged the case and predetermined

to dismiss plaintiff from employment. This act of prejudgment, which

suggests a lack of openmindedness by defendants, constitutes a denial

of due process of law. Prejudgment of a case by a judicial or quasi

judicial body in addition to denying due process of law mandates

granting plaintiff relief from that judgment. Gibson v. Berrvhill,

_____U. S._____, 36 L. Ed. 2d 488 (1973); Ferguson v. Thomas, 430 F.

2d 852, 861 (5th Cir. 1970)(dissent of Judge Thornberry).

Once having determined that plaintiff has been denied pro

cedural due process of law, and having decided that he should pre

vail, the Court must fashion the relief which is most appropriate

under the circumstances of the case. Both the interests of plaintiff

and of the students and parents of Sumter County must be considered.

Plaintiff's rights to a fair hearing shall be effectuated

by requiring defendants, in their official capacity, to afford the

plaintiff a hearing on the charges served upon him November 15, 1973.

-5-

If a procedural deficit appears, the matter should,

at that point, be remanded to the institution for

its compliance with minimum federal or supplemen

tary academically created standards.

Ferguson v. Thomas, 430 F. 2d 852, 858 (5th Cir. 1970).

Pursuant to the provisions of Florida Statutes § 120.09(1),

defendants shall disqualify themselves from hearing plaintiff's case

and shall request the appointment of a hearing examiner to do so.

Furthermore, the defendants, in their official capacity, shall be re

quired to grant plaintiff the back pay ho has lost from the time o.

the improper suspension without pay on November 20, 1973, until such

time as he has been afforded a proper hearing. The defendants shall

not be required to reinstate plaintiff into the classroom, and the

November 6th suspension from teaching with pay shall remain in full

force and effect pending the aforesaid hearing.

The Court in an order entered herein February 8, 1974, dis-

'massed the School Board of Sumter County as a party defendant because

it is not a "person” within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. § 1983, and is

in the nature of a municipality. City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U. S.

507, 37 L. Ed. 2d 309 (1973); Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961);

Campbell v. Masur, 486 F. 2d 554 (5th Cir. 1973).

Nevertheless, defendants as individuals and in their official

capacities are "persons" within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. § 1983, and

are, therefore, subject to liability for violating Section 1983. Al

though the Supreme Court in City of Kenosha v- Bruno, supra, and the

Fifth Circuit in Campbell v. Masur, supra, overruled the portion of

Harmless v. Sweeney Independent School District, 427 F. 2d 319 (5th

Cir. 1970), which held a school district to be a "person". Part II

of Harkless has never been overruled. That portion of the opinion

clearly holds that school officials are "persons" and can be compelled

to discharge their official duties by means of a Section 1983 action.

-6 -

This order shall constitute the Court's findings of fact

and conclusions of law. Therefore, it is

ORDERED AMD ADJUDGED:

That defendants JOE STRICKLAND, ERWIN BRYAN, JR., JOHN W.

WALLACE C. AUBREY CARUTHERS, JOE D. MERRITT and SHERMAN G. WILSON,

individually, and in their official capacities as members of the

School Board of Sumter County, Florida, are enjoined from failing

to provide plaintiff with a hearing as soon as practicable on the

charges served upon him on November 16, 1973; and, it is further

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED:

That, pursuant to the provisions of Florida Statutes §

120.09(1), defendants, individually, and in their official capacitie

as members of the School Board of Sumter County, Florida, are en

joined from failing to disqualify themselves from hearing plaintiff

case and shall request the appointment of a hearing examiner to do

so; and, it is further

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED:

That defendants, individually, and in their official capa

cities as members of the school board of Sumter County, Florida, are

enjoined from failing to allocate moneys for and pay moneys to plain

tiff for the back pay he has lost from the time of his improper sus

pension without pay on November 20, 1973, until such time as he has

been afforded the aforesaid hearing; and, it is further

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED:

That plaintiff's suspension from teaching with pay, im

posed on November 6, 1973, remains in full force and effect pending

the outcome of the aforesaid hearing.

DONE AND ORDERED at Jacksonville, Florida, this 18th day

of March, 1974.

Original signed:

CHARLES R. SCOTT

V