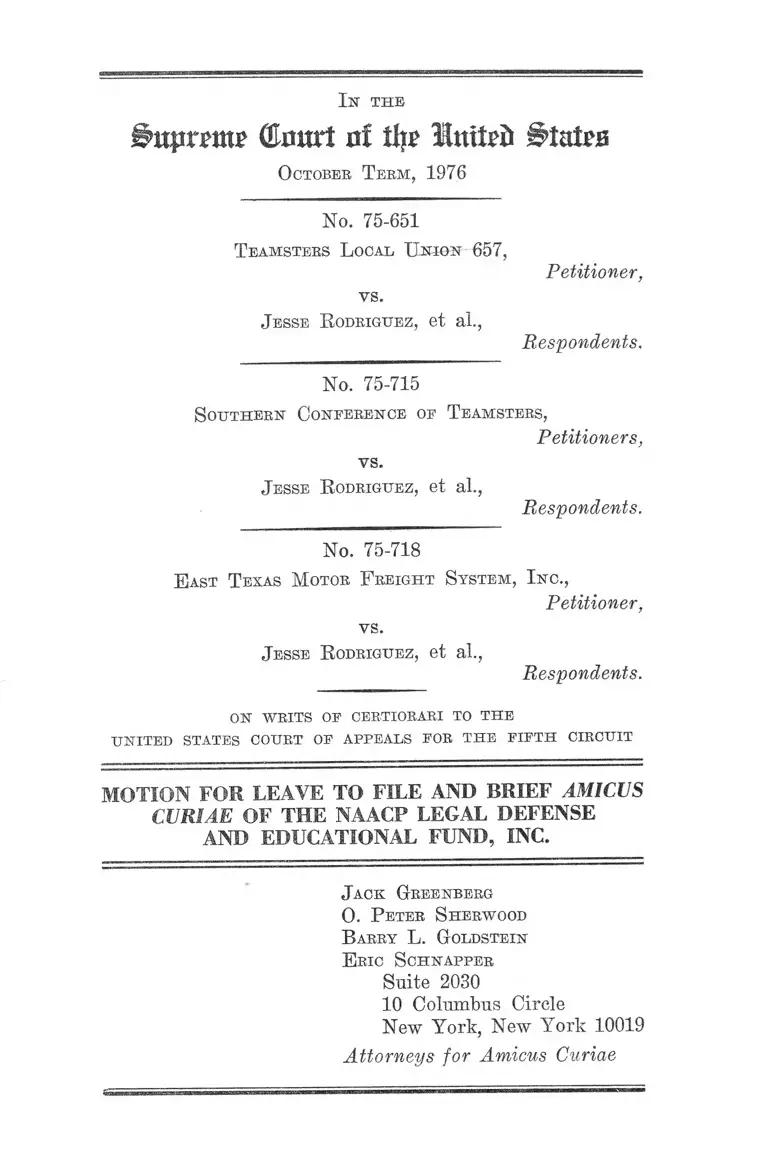

Teamsters Local Union 657 v. Rodriguez Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Teamsters Local Union 657 v. Rodriguez Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1976. d7c353e6-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93c4f104-c11d-431f-b6d5-b7ddab4278d7/teamsters-local-union-657-v-rodriguez-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

Bupxmxz OXrntrt of tty lntt?& States

October T erm, 1976

No. 75-651

T eamsters L ocal Union 657,

Petitioner,

vs.

Jesse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-715

S outhern Conference of T eamsters,

Petitioners,

vs.

J esse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-718

E ast T exas M otor F reight System , I nc .,

Petitioner,

vs.

Jesse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED states c o u r t of appe als for t h e f if t h CIRCUIT

In th e

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Jack Greenberg

0 . P eter S herwood

B arry L. Goldstein

E ric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

I N D E X

ARGUMENT---- PAGE

The Writs Should Be Dismissed as Improvidently

Granted ...... .................. -................. .............................. 2

I. The Company Petition.......... ................... .......... 3

1. Reliance on “Mere Statistics” ....... ....... ..... 3

2. Class A ction ....................... ............................ 8

3. The City-Road No Transfer Rule ............. . 10

4. The Inter-Terminal No Transfer Rule .... 11

5. The Individual Claims ................... ............ 13

II. The Union Petitions ............ ..... ....................... 16

C onclusion _________ ______ ____ - .............. ................... -............ 18

A p p e n d ix .................. ................................ ........ -...... .......... la

T able op A u t h o r it ie s

Cases:

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen v. Bangor &

Aroostook R.R., 389 U.S. 327 (1967) „ ...................— 18

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 47 L.Ed.2d

444 (1976) ............. ............. - .... ....... ........ -......... ......... 13

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, No. 76-636 ...... ...... ..... ...... ----------------- -----.... 17

McCarthy v. Bruner, 323 U.S. 673 (1944) ................... 7

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) 15

Phillips v. New York, 362 U.S. 456 (1964) .................. 18

11

PAGE

United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 4 EPD

TT 7624 (W.D.N.C. 1971) _______________ _____ 11

United States v. East Texas Motor Freight System,

Inc., 10 EPD I) 10, 345 (N.D.Tex. 1975) __ _____ passim

United States v. Terminal Transport Co., 11 EPD

« 10,704 (N.D.Ga. 1976) ............................ ..... ............. 11

United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc., No. 74-453

(D.D.C.) ............. .......... ....................... ...... ....... ............ 6

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir.

1976) .............. ..................... ............................ ................. 13

Other Authorities:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

Rule 60(b)(6) ....... ..... .......... ............... ................ . 9

United States Census of Population, 1970 ................... 13

I n THE

&upran? (Enurt ni tiff Imti'in States

O ctober T erm , 1976

No. 75-651

T eamsters L ocal I 'xtox 657,

vs.

Petitioner,

J esse R o drigu ez , et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-715

S o u t h e r n C o n fe re n ce of T e a m ste r s ,

Petitioners,

vs.

J esse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-718

E ast T exas M otor F reight S ystem , I n c .,

Petitioner,

vs.

J esse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

on w r it s o f c e r t io r a r i to t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOE THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION F0M LEAVE TO

FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

hereby moves to for leave to file the attached brief as

amicus curiae.

2

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation incorporated under the

laws of the State o f New York. It was formed to assist

Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by the prose

cution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its purposes

include rendering legal services gratuitously to Negroes

suffering injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For

many years attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund have

represented parties in employment discrimination litigation

before this Court and the lower courts. The Legal Defense

Fund believes that its experience in employment discrimi

nation litigation may be of assistance to the Court. The

proposed brief is submitted in support of respondent

though advancing reasons somewhat different than those

relied on by the courts below.

W herefore, the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., respectfully prays that this motion be

granted, and that the attached brief be filed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

0 . P eter Sherwood

B arry L. Goldstein

E ric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

In the

gutpramp tour! of % Mnittft Zlatas

October T erm, 1976

No. 75-651

T eamsters L ocal U nion 657,

Petitioner,

vs.

Jesse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-715

Southern Conference of T eamsters,

Petitioners,

vs.

Jesse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 75-718

E ast T exas M otor F reight System , I nc .,

Petitioner,

vs.

Jesse R odriguez, et al.,

Respondents.

on w r it s of certiorari to t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC.

2

ARGUMENT

The 'Writs Should Be Dismissed as Improvidently

Granted.

The issues actually presented by these cases are sub

stantially different than those which were raised in the

petitions for certiorari. In June, 1972, petitioner East

Texas Motor Freight (hereinafter ETM F), together with

the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, was sued by

the United States. The government’s complaint, as the

complaint in this action, alleged systematic discrimination

against blacks and Mexican-Americans, and sought broad

monetary and injunctive relief. In April, 1975, an extended

trial was held in United States v. East Texas Motor Freight

System, Inc. (hereinafter US v. ETM F ) ; on May 28, 1975,

the District Court upheld the government’s claim of dis

crimination and awarded to minority employees at present

or former road terminals injunctive relief more stringent

than that awarded in this case.1 10 EPD f[10,345. The

parties in US v. ETMF have appealed only certain por

tions of the relief, and do not there contest the finding

of discrimination.2 The company in the instant case ex

1 Under the Fifth Circuit decision in this ease, a city driver who

transfers to the road will have carry over seniority dating from

the point at which he had three years of truck driving experience.

505 F.2d 40, 63, n. 29, 62. Under US v. ETMF, transferring em

ployees will have two more years of seniority, dating from the

point at which they had one year of experience.

2 The company did not appeal. The union appeal raises three

questions: whether the union locals were necessary parties,

whether the locals and Southern Conference were alone respon

sible for the seniority system, and whether the seniority relief

ordered by the district court should have been based on a more

individualized analysis of the employment history of each mi

nority worker. No. 75-3332, 5th Cir.

3

pressly relies on US v. ETMF for its own purposes,3 4 * but

otherwise ignores developments therein.

The evidence which petitioners assert is required to

support the decision below, which they object is absent

from the record in this case, is to a substantial degree

present and uncontested in US v. ETM F} As to certain

issues and class members, the instant case has been ren

dered partially moot by US v. ETM F} These circum

stances were known to petitioners prior to the grant of

certiorari, and were not disclosed to the Court. In addition,

of the questions originally presented by the petitions,

some have, for all practical purposes, been abandoned,

and others are not supported by the record in this case.

In light of these considerations, amicus believes that cer

tiorari was improvidently granted and that the writs should

be dismissed.

I. The Company Petition6

1. Reliance on “ Mere Statistics”

The only question presented by the company’s petition

which is pressed in recognizable form in its brief is

“ [w]hether the Court of Appeals properly relied on un

differentiated statistical evidence in entering a finding of

liability in favor of the Plaintiff class.” 7 The company

asserts that the sole evidence of discrimination was the

mere fact that, of several hundred road drivers employed

3 Company Brief, p. 34.

4 Amicus has lodged with the Court a copy of the relevant por

tions in the record in TJS v. ETMF. That document, headed “ Ex

hibit of Amiens Curiae, N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc.” , is referred to hereafter as EA.

6 See p. 6, infra.

6 No. 75-718.

7 Company Petition, pp. 3, 26-31; Company Brief, pp. 2, 37-54.

4

by defendant prior to 1970, none was black or Mexiean-

American. Such evidence, the company argues, was insuffi

cient to constitute a prima facie ease of discrimination

against minority drivers.8 The company’s petition present

ed a frontal attack on the use of statistics, and suggested

certiorari was appropriate to consider in broad terms

the efficacy and reliability of such evidence.9 In its brief,

however, the company largely restricts its discussion to

the relevance of such evidence to minority employees at

city terminals,10 and does not vigorously contest its proba

tive value for road terminals.11

At the trial in US v. ETMF, Mr. George Smith, ETMF’s

personnel director from 1952 to 1967, testified candidly

as to the policy of the company regarding the hiring of

non-white road drivers:

Q. (By Mr. Gadzichowski) What was the policy of

the company at that time?

A. The company, so far as road drivers was con

cerned, did not want to employ minorities as road

drivers.

Q. When you speak of minorities, do you mean

Blacks and Spanish surnamed Americans?

A. I do.

8 Company Brief, p. 42.

9 Company Petition, p. 30:

“ In light of the growing reliance on statistical evidence

to prove liability in civil rights eases and the explosion of

complex, complicated class actions in this area, the Court

should grant the Petition herein and articulate the burden

of proof required by a class action Plaintiff, both in terms

of the quantity and quality of statistical evidence necessary

to produce an inference of discrimination and the additional

evidence required to support that inference sufficiently to

establish a prima facie case.”

10 Company Brief, pp. 40-49.

11 See Company Brief, p. 46, n,15.

5

Q. Were you aware of that policy that the company

had?

A. I was.

Q. Was there any question in your mind that that

was the policy?

A. There was not.

Q. And did the policy continue during your tenure

at East Texas Motor Freight?

A. It did.

Q. Was it still in existence at the time you left? ■

A. It was.12

The government offered a 1966 memorandum to Smith from

ETMF’s Atlanta office describing a black driver and con

cluding, “ So the long and short of it is that if and when

we must hire colored boys, this one would be a good one

. . .” 13 At least until 1963 this policy of discrimination was

implemented by an ETMF application form which required

the prospective employee to state his race in the following

box :14

X I__________ ::____ :-----i— —— :-----------1— -----------

LINEAGE

Che \ o W u cC

English-!ri*h-French-H«rbrew-Germ«n. Etc.

Black employees testified that they were expressly told

road driver jobs, both permanent and casual, were for

whites only.15

12 EA 38.

18 EA 276.

14 EA 234, 236, 244, 245, 282-288.

16 EA 75-78, 80, 127-128.

6

On the basis of this and other testimony, the District

Court in US v. ETM FU concluded:

The evidence showed that discrimination occurred

against Blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans who

applied for or attempted to transfer to over-the-road

jobs with ETMF and its acquired companies. When

they sought to transfer, their seniority for bidding,

layoff and recall purposes was lost. As a result of

losing these rights, there has been little desire to

transfer to over-the-road jobs. The seniority system

of the Unions is a barrier to the movement of minor

ities from city or other bargaining unit jobs to over-

the-road jobs. It effectively locks Blacks and Spanish-

surnamed Americans into their jobs and means that

seniority for minority employees [must be] built up in

other than over-the-road bargaining units.

Neither defendant in that action appealed from this finding

of discrimination.16 17 The injunctive relief ordered by the

District Court in US v. ETMF covers at least 76 of the 199

class members in this action,18 and 59 of them have already

entered into a cash settlement with the company.19

16 10 EPD 1(10,345, p. 5416 (N.D. Tex. 1975); EA 293.

17 See n.2, supra.

18 It includes certain city drivers at the El Paso, Dallas, San

Angelo, Longview, San Antonio and Houston terminals. See EA

296-312. Although a large number of trucking companies have

in the past had policies forbidding transfers from city to road

driver positions, most of them agreed in 1974, pursuant to a con

sent decree in United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc., No.

74-453 (D.D.C.), to permit minority city drivers to transfer to

the road. The validity of such policies is thus of less import than

suggested by the petitions.

19 EA 299-303. The liability of the International to the 79 cov

ered employees is the subject of a pending appeal in US v. ETMF.

7

In short, petitioners are asking the Court to issue a far

reaching decision as to -the probative value of “mere sta

tistics” under Title VII in a case which there is known to

be massive non-statistical evidence of racial discrimination

as well as an uncontested judicial finding of discrimination.

Regardless of whether, in the narrowest of senses, the rec

ord could be said to present a question about the eviden

tiary significance of such statistics, the underlying contro

versy obviously does not. M cCarthy v. Bruner, 323 U.S.

673 (1944). This is manifestly not an appropriate case in

which to decide such matters; had the Court known of the

above-described facts at the time when the certiorari peti

tions were under consideration, it is unlikely that certiorari

would have been granted on this issue.20

20 The Company’s Petition presented a related question no

longer vigorously pursued, at least in its original form : “Whether

the Court of Appeals, consistent with due process, may ignore a

pre-trial stipulation, and sua sponte make a finding of liability

without affording the Defendant an opportunity to present evi

dence to the District Court.” The petition dwelt at length on the

fundamental unfairness of being held liable -without having an

opportunity to produce evidence in opposition to the claim of

class-wide discrimination. Company Petition, pp. 10-21.

In its brief, however, the Company no longer presses this con

tention. No specific suggestions are made as to what evidence the

Company would have introduced had it “known” the question of

class-wide discrimination was at issue in the district court. This

is not surprising in light of the evidence in US v. ETMF. The

Stipulation referred to in the question presented is now relied on

solely insofar as it bears on whether the court of appeals erred

in approving the case as a class action. Company Brief, pp. 14,

25. Although the company asserts that it “concentrated” its de

fense on the qualifications of the named plaintiffs, Company Brief,

p. 25, the record establishes that this was not the case. App. 141-

193. The company now concedes that the Fifth Circuit decision

affords it an opportunity, at the second stage of this bifurcated

proceeding, to introduce evidence that, because of a lack of in

terest or qualification, any individual class member was not in

jured by the policy of hiring only white road drivers and is thus

not entitled to relief. Company Brief, pp. 52-53.

8

2. Class Action

The question presented by the original petition was

“ whether absent a class action hearing or an equivalent

opportunity to present evidence on the question of the ap

propriateness of the class the Court of Appeals may certify

the litigation as a class action and enter a finding of liability

in favor of the Plaintiff class.” 21 (Emphasis added) On its

face, this question indicated that the only relief to be

sought, were certiorari granted, would be a decision afford

ing petitioner an opportunity to present such evidence.

In its brief, however, the company, rather than seeking

a remand for an evidentiary hearing, now urges that this

Court reinstate the district court’s denial of class action

treatment.22 The company advances nine legal arguments

as to why this case is not an appropriate class action.23

The company also offers four reasons why the scope of

the class should be narrowed.24 * These, however, are not the

21 Company Petition, p. 3.

22 Company Brief, pp. 13-36.

23 (1) That plaintiffs abandoned the class aspect by inaction.

Company Brief, p. 15, n, 3, 28. (2) That plaintiffs stipulated it

was not to be a class action. Id., p. 16. (3) That plaintiffs violated

their responsibility under Rule 23 to move for a class action deter

mination. Id., pp. 14, 16, 18-21. (4) That the case was not in fact

tried as a class action. Id., pp. 25, 29, 37. (5) That the district

court acted within its discretion. Id., pp. 15, 23. (6) That plain

tiffs failed to adduce evidence to support a class action. Id., pp. 14,

16-18. (7) That the court of appeals erred in stating the propriety

of a class action was uncontested. Id., p. 30. (8) That all Title

Y II suits are not appropriate class actions. Id., pp. 31-32. (9)

That a class should not be certified after a decision on the merits.

Id., p. 27.

24 (1) That there may be different types of discrimination at

each terminal. Id., p. 33. (2) That city drivers at road terminals

are covered by 77$ v. ETMF. Id., p. 34. (3) That the interests of

city drivers at road terminals conflict with those of city drivers at

city terminals. Id., pp. 34-35. (4) That most applicants for driving

jobs only want to work in the town where they apply. Id., pp.

35-36.

9

questions regarding which certiorari was sought and

granted.

The company’s 67 page brief contains a single sentence

pro forma objection to the alleged denial of an opportunity

to present argument and evidence.25 In fact, however, the

company in the Fifth Circuit did brief extensively the ques

tion of or whether this case was a proper class action.26 Le

gal argument was also presented on the propriety of a class

action in the Company’s Petition for Rehearing and Sug

gestion for Rehearing En Banc,27 and that Petition ottered

no intimation that the company had in any way been pre

vented from advancing legal argument in its brief or peti

tion in the Fifth Circuit. The company has yet to offer

any indication as to what evidence it would have wanted

to introduce as to the propriety of a class action, why it

would have been relevant, or even whether it has or would

seek to introduce such evidence on remand. If, by any

chance, the company has relevant evidence and can demon

strate on remand that the earlier proceedings provided no

adequate notice that the evidence was called for, the com

pany may introduce it and seek appropriate modification

of the class action order under Rule 60(b)(6), Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure.

26 Company Brief, p. 29.

26 Brief of Appellee-Defendant. Bast Texas Motor Freight System,

Inc., No. 73-2801, pp. 11-18; EA 313-321.

27 Pp. 12-15; BA 322-326. Many of the arguments advanced in

this Court in opposition to class action treatment were not advanced

below, despite ample opportunity to do so. The Company’s real

grievance seems to be not that it had no such opportunity, but

that it failed to put the opportunity to good use.

10

3. The City-Road No Transfer Rule

The company argues that its rule prohibiting employees

from transferring from jobs as city drivers to positions as

road drivers was adopted in order to “maintain” the higher

standards adopted two decades ago for road drivers be

cause of a serious accident problem.28 The rule is of vital

importance to minority drivers, since it prevents them

from moving from the lower paid city driver jobs, to which

they were confined on the basis of race until at least 1974,

into the more lucrative road jobs.29 What relevance this

contention has to the questions presented is not apparent.

In any event, this explanation has no basis in fact. On its

face it is unpersuasive, for higher age, experience or other

standards for road drivers could be preserved merely by

providing that a city driver could transfer to the road

only if he met the higher standards. The Appendix page

cited by the company in support of this explanation con

tains neither reference to differences in standards nor testi

mony with regard to ETMF’s safety record in the 1950’s ;

rather, the rule is there explained as a way to maintain

continuity of relationships between city drivers and their

customers, an argument long ago abandoned. App. 167.

The previous page of the testimony offers as the primary

reason for the rule a paternalistic desire to protect the

“best interest” of city employees who might be foolishly

tempted by the higher wages of road jobs to give up their

28 Company Brief, p. 7; Company Petition, p. 7.

29 In US v. ETMF, the company stipulated average earnings at

5 typical terminals were as follows:

Classification 1970 1971 1972

Road Driver $12,368 $15,333 $18,100

City Employee 9,348 11,339 12,952

(City driver, etc.)

It further stipulated that average road driver out of pocket

expenses in 1972 were about $50.00 a week. EA 289-291.

11

city seniority and neglect their “ family responsibilities” .

App. 166.

The actual reason for the rule was candidly disclosed in

US v. ETMF by the former company official who was

ETMF’s personnel director when the rule was adopted:

Q. Do you know why that No Transfer Policy was

put forth and implemented?

A. Yes, to prevent Blacks who are in the city opera

tion transfering to the road operation.

Q. Is there a specific city operation that Blacks were

seeking to transfer from the city to the road?

A. St. Louis, among others.30

Although the Southern Conference urges that all drivers

“prefer” the “ traditional” 31 separation of city and road

jobs, with a loss of seniority for any transferring employee,

that is not so. Teamster contracts road and city rosters

are merged in the northeast and for certain midwest com

panies, and transfers without seniority loss are authorized

in several states.32

4. The Inter-Terminal No Transfer Rule

The Company expressly recognized in its petition that,

if there were a past policy of not hiring minority road

drivers, the prohibition against transfers between terminals

would have an impermissible “ lock in” effect if “minority

drivers were hired in city-driver-only terminals in dispro

80 BA 47. There is substantial evidence that whites were in fact

allowed to transfer to the road after adoption of the no-transfer

rule. See BA 85, 98-100, 104, 156, 163, 228, 233-274.

31 Southern Conference Petition, 8-9.

82 See, e.g., United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 4 BPD

If 7624, p. 5441 (W.D.N.C. 1971); United States v. Terminal Trans

port Co., 11 BPD |[ 10,704, p. 6940, n. 9 (N.D. Ga. 1976).

12

portionate numbers.” 33 The company advises the Court

that “ There is no evidence in the record to support such an

assertion.” 34 The Southern Conference alleges that the

number of minority city drivers at each terminal “ generally

reflected the racial-national origin make-up of the respec

tive communities in which the terminals are located.35 Both

of these assertions are refuted by the record in this case.

Of the black drivers in Texas, 91.58% (87 of 95) work at

city only terminals, as do 66.46% of Mexican Americans

(68 of' 104). Only 36.95% of white drivers work at city

only terminals (211 of 571).36 This is precisely the dis

proportionate concentration of minority drivers at city only

terminals that the company properly recognized would re

quire abandonment of the prohibition against inter-termi

nal transfers.

Neither is it the case, as suggested by the Southern Con

ference, that minority city drivers are evenly distributed

among the 20 terminals with city drivers. On the contrary,

87.36% of all black city drivers work at just 2 terminals,

Houston and San Antonio; 86.53% of all Mexican-American

drivers work at Houston, San Antonio or El Paso. There

are 13 city terminals with no minority city drivers, com

pared to 138 white city drivers. Minority employees con

stitute 76.65% of all city drivers at Houston, San Antonio,

and El Paso, and only 7.26% of the city drivers at the

remaining 17 terminals. As a practical matter, city driver

was a non-white job in those three terminals, and a white

job everywhere else. Nor can this pattern be explained by

variations in the population; at the 13 terminals with no

33 Company Brief, p. 40, n. 10; Company Petition, pp. 18, 27.

34 Company Brief, p. 40, n. 10.

35 Southern Conference Brief, p. 8.

36 See p. la, infra.

13

minority drivers, blacks and Mexican-Americans constitute

24.76% of the population. See p. la, infra.

The company suggests that its failure to hire virtually

any minority road drivers may be the result of an absence

of minority truck drivers in Texas. Census data reveals,

however, that 39.62% of all truck drivers in the state are

black or Mexican-American,37 compared to 26.06% of all

ETMF truck drivers and 1.64% of ETMF road drivers.

In the 18 cities, other than Houston, San Antonio, and El

Paso, where only 7.26% of ETMF’s drivers were non-white,

39.40% of the drivers in the area were non-white. In the

13 cities where none of ETMF’s drivers were black or

Mexican-American, 32.19% of the area drivers were black

or Mexican-American. See, p. 2a, infra.

5. The Individual Claims

The company has briefed at length the question of

whether it was guilty of discrimination against the indi

vidual plaintiffs.38 It argues that each of the plaintiffs was

unable to meet either the age, weight or driving record

requirements,39 and that one of them had been involved in

on-the-job accidents.40 The question of whether the court of

appeals erred in its treatment of the individual claims has

not the slightest relationship to any of the questions pre

sented by the petition.

As this Court recognized in Franks v. Bowman Trans

portation Co., 47 L.Ed.2d 444, 446, n. 32 (1976),41 a

company cannot ground its refusal to hire a black appli

37 United States Census of Population, 1970, vol. 45, Texas,

Tables 171, 179, pp. 1583, 1819-21.

38 Company Brief, pp. 55-66.

39 Id., pp. 63; see also 21-22, n. 6.

40 Id., p. 8.

41 See, e.g., Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159, 1177-78

(5th Cir. 1976) and case's cited.

14

cant on his failure to meet a standard or requirement which

has not been uniformly applied to whites. The record in

US v. ETMF reveals literally hundreds of instances in

which whites were hired as road drivers who did not meet

the age, weight, education or experience requirements

nominally adhered to by the company.42 In 1966 the com

pany personnel director wrote a memorandum which

stated:

With respect to job specifications, it is recommended

that they be kept flexible as in the past. Our hiring

limits have always been taken as guidelines, not so

specific “yes” or “no” criteria. Since we place a great

deal of emphasis on the individual being considered

for any position, we will wish to remain flexible enough

to deviate from our “guidelines” of policy for an out

standing applicant, who may not be the “ policy” age

or possess the “policy” experience, etc. This practice

could be a difficult one to defend, if we were ever called

upon to justify non-hiring of a negro over a white for

a given job. We must handle future non-selection of

negro applicants over whites for the same job on a

basis other than not meeting specific standards, in

view of the fact that we have deviated from our “ stan

dards” to hire others for the same job.43

The director testified at trial in US v. ETMF that the stan

dards were only informal “guidelines” , and that they were

often disregarded.44 On the basis of this evidence the Dis

trict Court in US v. ETMF held:

ETMF did not strictly comply with stated company

hiring standards through the years when hiring drivers

42 BA 149-219, 227-232, 268-274.

43 EA 279.

44 BA 39, 56-60.

15

for over-the-road jobs. Deviations may be found from

every standard regarding age, education, safety record,

and driving experience, although some driving experi

ence was generally required.45

Although the company objects that plaintiffs are unqual

ified because they lack 3 years of road driving experience,

in 1972 it offered to waive that requirement for any of its

hundreds of city drivers at road terminals who wished to

transfer to the road.46 Clearly these allegedly “ stringent” 47

standards were used, inter alia, as a pretext to reject quali

fied blacks and Mexican-Americans; they should be given

no credence by this Court. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 TT.S. 792, 804 (1973).

The company further suggests that the individual plain

tiffs would have been treated no differently had they been

qualified whites, since the San Antonio terminal employs

only city drivers and cannot hire for other terminals.48

The company director of safety, however, testified in US

v. ETMF that the officials at one terminal would inform

applicants of vacancies at other terminals.49 The record

in that case reflected instances in which applicants at one

terminal were referred to another and in which applica

tions were forwarded from one terminal to another.50 Man

ifestly none of this would have been done for a minority

driver, at San Antonio or elsewhere, who indicated an in

4510 EPD 10,345, p. 5416 (N.D. Tex. 1975); EA 293.

46 Compare Company Brief, p. 8, with App. 73.

47 Company Brief, pp. 6-7; Company Petition, p. 7.

48 Company Brief, pp. 53-59.

49 EA 147-148.

60 EA 183 (Victor Beeves), 220-26 (James White), 228 (Robert

Mckinley, Roger Amstutz), 229 (Martin Treece, Donald Taylor),

230 (James White), 232 (Donald White).

16

terest in road jobs which were only available at another

terminal.

Although in this action the company vigorously objects

to permitting the named plaintiffs to transfer to road jobs

at another terminal, the consent decree signed by the com

pany two years ago in US v. ETMF permits such transfers

to all minority city drivers in Texas who sought to transfer

between 1965 and 1974, regardless of whether they have

road experience. App. 108, 432. Since each of the named

plaintiffs applied for such a transfer in 1970, each of them

is literally covered by both the consent decree and the

injunctive relief ordered in US v. ETMF. Thus the com

pany agreed in US v. ETMF to the very relief for the

named plaintiffs which it here opposes.61

II. The Union Petitions

Although the Southern Conference petition presented 4

questions, the Conference has elected to pursue only two of

them.62 The abandoned questions dealt with the sufficiency

of the evidence of discrimination, and thus bore on the

propriety of the injunctive relief ordered by the court of

appeals.63 The two questions which the Conference has

elected to pursue deal solely with whether the finding of

union liability was proper in view of various factual cir

cumstances emphasized by that petitioner.64 The Confer- * 52 * 54 * * * *

61 Counsel for amicus have been unable to ascertain with

certainty why this transfer has not occurred.

52 See Southern Conference Brief, pp. 2-3, n. 2.

63 The Conference “ defers” on those questions to the arguments

of the company, discussed supra.

54 The Conference argues that the seniority lock-in provisions of

its collective bargaining agreement never had any effect because

minority employees were also locked in by the company’s no

transfer rule. It could, of course, be argued with equal cogency

that the company rule never had any effect because of the union

17

■enee urges that these circumstances compel that conclusion

that company alone should bear monetary responsibility for

the injury suffered by the plaintiff class.* 65

The Local Union complains that, on the particular facts

of this case, it should not be held liable. It stresses that,

under the delegations of authority within the Teamsters,

it is the International and Conference which negotiate the

actual contracts and that they alone should be liable. The

International, in US v. ETMF and in International Broth

erhood of Teamsters v. United States, No. 76-636, advances

the opposite contention, urging that the locals alone are

liable because they are the entities which approve the con

tracts.

Whatever the merits of these conflicting contentions, the

sole consequence of the Fifth Circuit’s finding of liability

against the Conference and Local is to authorize the district

court to apportion some part of the total back pay liability

rule. Whichever may be the “real” cause of the inability of

minority drivers to transfer, once that rule is enjoined the other

rule would become operative and have to be enjoined as well.

The Conference also objects to monetary liability on the ground

that the Teamsters actively support placing minority victims of

discrimination in their “rightful place” . Conference Brief, pp. 33-

34. The record in this case reveals not a single instance in which

union officials took action to prevent or remedy ETMF’s flagrant

policy of discrimination; the record in US v. ETMF, reveals a

refusal to do so. EA 87-88, 113-119.

65 The Conference Brief discusses at length whether the injunc

tive relief ordered below was excessive, an issue unrelated to the

original questions presented. Conference Brief, pp. 23-36. The

Conference suggests that minority city drivers who were the

victims of discrimination be given carry over seniority only from

the date on which they applied for road jobs. The record in US v.

ETMF, however, shows, as the Conference well knows, that the

company refused to permit and actively discouraged applications

by non-whites for road jobs, and that minority drivers were

detered from applying by the well known ETMF policy of dis

crimination. EA 99a, 100a, 100b, 104a, 104b, 107, 107a, 143-5.

18

to them. A careful reading of the opinion below, however,

reveals that the court of appeals expressly recognized the

“broad discretion” of the district court in allocating back

pay liability among the defendants. All of the arguments

made here by the Local and Conference can be made in the

district court and, if sound, might lead that court to fix

the unions’ financial responsibility at a nominal amount, or

even place the entire responsibility on the company. Since

such a decision would afford the Local and Conference all

the relief they seek here, it is apparent that the questions

presented by the union briefs are interlocutory in nature

and that the grant of certiorari was premature. Brother

hood of Locomotive Firemen v. Bangor & Aroostook R.R.,

389 U.S. 327 (1967).

CONCLUSION

The questions actually raised by this case are not those

suggested by the petitions. To a significant extent the

petitioners have abandoned the questions originally pre

sented, and now seek to litigate issues not raised by the

petitions and as to which certiorari was not and would not

have been granted. Certain pivotal arguments of the peti

tioners are without foundation in the record itself. Phillips

v. New Fork, 362 U.S. 456 (1964). Many of the factual as

sertions and defenses advanced by the petitioners, though

plausible within the narrow confines of the record, are

manifestly insubstantial in view of the evidence and find

ings in TJ8 v. ETMF. In view of the fact that counsel for

the company and Southern Conference were counsel in

US v. ETMF, they should have disclosed the circumstances

of that case in their petitions and briefs.

At best the Court is invited to write a difficult and far

reaching opinion about a hypothetical case which would ex

19

ist if tlie facts were not as they are now known to be. The

invitation should be declined, and the writs of certiorari

should be dismissed as improvidently granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

0 . P eter Sherwood

B arry L. Goldstein

E ric S chnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

la

APPENDIX

ETMF Drivers

Terminal

Abilene: City

Amarillo: City

Atlanta*: City

Austin: City

Beaumont: City

Brownwood: City

Dallas: Road

City

El Paso: Road

City

Fort Worth: City

Henderson: City

Houston: City

Longview: Road

City

Lubbock: City

Lufkin: City

Marshall: City

Odessa: City

Pecos: Road

San Angelo: Road

City

San Antonio: City

Texarkana: City

Road

Tyler: City

February 29, 1972

White Black

Drivers Drivers

11 0

5 0

2 0

8 0

29 3

5 0

59 0

107 5

52** 0

0 1

35 0

2 1

47 73

32 0

28 1

8 0

11 0

7 0

15 0

15 0

33 0

18 1

6 10

9 0

6 0

21 0

Mexican City

American Minority

Drivers Population

0 15.65%

0 11.79%

0 •—

0 27.50%

0 33.69%

0 11.69%

0 32.93%

11

3 60.41%

22

0 28.53%

0 28.08%

37 37.85%

0 19.95%

0

0 23.34%

0 30.43%

0 34.96%

0 19.52%

0 52.25%

0 24.22%

0

31 59.76%

0 28.85%

0

0 23.71%

* Population under 10,000, census data on minority population

not published.

« This appears to include 2 Indians.

Source: App. 322, 353-415; United States Census of Population,

1970, vol. 45, Texas, Tables 40, 91, 97, 108, 112.

2a

Appendix

Truck Drivers

At Places W ith ETMF Terminals

By Race

M exican

T otal B lack A m erican

P ercen t

M in ority

T erm inal D rivers D rivers D rivers D rivers

Abilene 627 18 39 9.09%

Amarillo 1,161 74 68 12.23%

Atlanta* — — — -—

Austin 906 259 250 56.18%

Beaumont 865 550 17 65.54%

Brownwood** 276 7 8 5.43%

Dallas 6,381 2,674 485 47.50%

El Paso 1,795 60 1,361 79.16%

Ft. Worth 2,648 871 177 39.57%

Henderson** 230 99 ### 43.04%

Houston 9,480 5,126 979 64.89%

Longview** 690 165 13 25.80%

Lubbock 981 76 176 25.69%

Lufkin** 445 154 6 35.95%

Marshall** 328 129 39.33%

Odessa 811 44 117 19.85%

Pecos** 358 5 329 92.73%

San Angelo 400 24 80 26.00%

San Antonio 4,002 493 2,463 74.86%

Texarkana 556 124 0 22.30%

Tyler 365 60 0 16.43%

* Population under

not published.

10,000, census data on minority population

** Data for these cities includes some transportation equipment

operatives other than truck drivers.

*** No Mexiean-Ameriean data published.

Source: United States Census of Population, 1970, vol.

Tables 86, 93, 99, 105, 110, 115.

45, Texas,

MEILEN PRESS JNC.-— N. Y. C 219