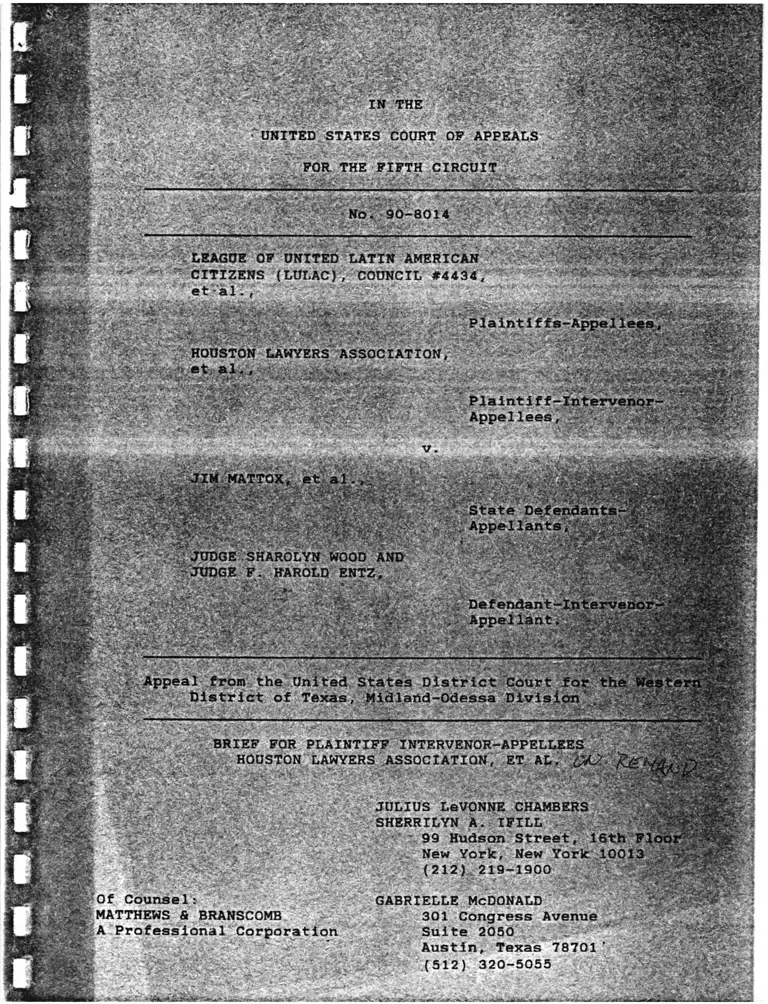

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Brief for Plaintiff Intervenor-Appellee

Public Court Documents

February 27, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Brief for Plaintiff Intervenor-Appellee, 1990. ddad492a-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93d67c04-7ef6-4236-adff-ca5270e8c5f1/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-council-4434-v-mattox-brief-for-plaintiff-intervenor-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

35 .v s rr^ T y jjJT

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

90-8014

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN

CITIZENS (LUI.AC), COUNCIL #4434

et al.,

HOUSTON LAWYERS ASSOCIATION

et. al

: JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD AND _.. ... - ——— —HAROLD ENTZ

Appeal from the United States District Court fo

district of Texas, Midlarid-Odessa Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF INTERVENOR-APPELLEES

^'HOUSTON LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, ET AL. fa

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson Street, 16th

New York, New York 100

Of Counsel:

MATTHEWS & BRANSCOMB

GABRIELLE MCDONALD

301 Congress Avenue

Suite 2050

Austin, Texas 78701

(512) 320-5055

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel certifies that the following listed

persons have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that the Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

1. The plaintiffs in this action: LULAC Local Council 4434,

LULAC Local Council 4451, LULAC (Statewide), Christina Moreno,

Aquilla Watson, Joan Ervin, Matthew w. Plummer, Sr. , Jim Conley,

Volma Overton, Willard Pen Conat, Gene Collins, A1 Price, Theodore

M. Hogrobrooks, Ernest M. Deckard, Judge Mary Ellen Hicks, Rev.

James Thomas.

2. The attorneys who represented the plaintiffs: William L.

Garrett and Brenda Hall Thompson of the law firm of Garrett,

Thompson & Chang; Rolando L. Rios of the Southwest Voter

Registration and Education Project; Susan Finkelstein of Texas

Rural Legal Aid, Inc..

3. The Harris County plaintiff-intervenors in this action:

Weldon Berry, Alice Bonner, Rev. William Lawson, Bennie McGinty,

Deloyd Parker, Francis Williams and the Houston Lawyers'

Association (HLA), a non-profit corporation.

4. The attorneys who represented the Harris County plaintiff-

intervenors: Julius Levonne Chambers, Sherrilyn A. Ifill, of the

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.; Gabrielle Kirk

fr(f 1 oi- f r r t W V- W i lb - .

McDonald of the law firm Matthews & Branscomb.

5. The Dallas County plaintiff-intervehors: Jesse Oliver,

Fred Tinsley and Joan Winn White.

6. The attorneys who represented the Dallas County plaintiff-

l

intervenors: Edward B. Cloutman III of the law firm of Mullinax,

Wells, Bdab & Cloutman; amd E. Brice Cunningham.

Q aa ^7. The defendants in this action: Jim Mattox, Attorney

General of the State of Texas; George Bayoud, Secretary of State

of Texas; the members of the Texas Judicial Districts Board:

Thomas R. Phillips, Mike McCormick, Ron Chapman, Thomas J. Stovall,

James F. Clawson, John Cornyn, Robert Blackmon, Sam B. Paxson,

Weldon Kirk, Jeff Ealker, Ray D. Anderson, Joe Spurlock II, Leonard

E. Davis.

Da* « $

8. The attorneys representing the defendants: Jim Mattox,

Mary F. Keller, Renea Hicks, Javier Guajardo, James Todd of the

Attorney General's Office of the State of Texas; John L. Hill of

the law firm of Liddell, Sapp, Zivley, Hill & LaBoon; and David R.

Richards.

9. The Harris County defendant-intervenor: Judge Sharolyn

Wood.

10. The attorneys representing the Harris County defendant-

intervenor: J. Eugene Clements, John E. O'Neill, Evelyn V. Keyes

of the law firm of Porter & Clements; and Michael J. Wood.

11. The Dallas County defendant-intervenors: Judge Harold

Entz, Judge Tom Rickoff, Judge Susan D. Reed, Judge John J. Specia,

Jr. Judge Sid L. Harle, Judge Sharon Macrae, Judge Michael D.

Pedan.

12. The attorneys representing the Dallas County defendant-

intervenors: Robert H. Mow, David C. Godbey, Bobby M. Ribarts,

Esther R. Rosenbaum of the law firm of Hughes & Luce.

13. The amici in this action: judges: Larry Gist, Loenard

P. Gilbin, Jr., Robert P. Walker, Jack R. King, James M. Farris,

li

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiff-intervenor appellees hereby request that this case

be set for oral argument. This appeal presents several distinct

and important legal issues. Although the resolution of many of the

issues on appeal should not be difficult in that they are governed

by settled Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit precedent, we believe

that oral argument would be valuable to the Court.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS............................. i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT ........................... iv

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ....................................

STATEMENT OF ISSUES ......................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .......................... 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS ......................................... 2

I. Introduction ....................................... 2

II. Facts Related to the "Gingles Factors" .......... 7

A. Blacks in Harris County Are Sufficiently

Numerous and Geographically Compact to

Constitute a Majority in a Single

Member District ............................. 8

B. Blacks in Harris County are Politically

Cohesive ................................... 9

C. Whites Sufficiently Vote as a Bloc in Harris

County District Judge Elections so as to ;

Defeat the Candidates of Choice of Black

Voters..........................................10

1. The Virtual Refusal of White Voters to

Support Black Candidates ............... 10

2. The Irrelevance of Party Affiliation . . 12

II. Senate Report Factors ............................. 15

A. History of Discrimination and Depressed

Socioeconomic Status ......................... 16

B. Racial Polarization in Voting ............... 17

C. The Use of "Enhancing" D e v i c e s ................. 18

D. Racial A p p e a l s ..................................19

F. Minority Electoral Success ................... 20

G. Tenuousness ....................................21

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT........................................22

A R G U M E N T ....................................................2 3

V

I. The Defendants' Attempt to Distinguish Harris

County Judicial Elections From Those Elections

to Which Section 2 Apply, Rests on

Fundamentally Erroneous Factual and Legal Arguments 23

A. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act Applies to

Elected Trial Judges ......................... 23

B. District Judges in Harris County are Elected

At-Large..................................... 25

II. The District Court Correctly Applied the Totality

of the Circumstances Test as Described in Gingles . 27

A. The District Court Applied the Correct

Standards to its Analysis of White Bloc

Voting in Harris County ..................... 28

1. The Standard for Interpreting

Statistical Analyses of Racially

Polarized Voting ....................... 28

2. Causation is Irrelevant to a

Determination of Polarized Voting . . . . 31

3. The Particular Salience of Elections

Involving Both Black and White

Candidates ................................ 31

B. The District Court's Findings on White Bloc

Voting in Harris County ..................... 32

1. The District Court was not Persuaded by

the Defendants' Claims Regarding the

Role of Party Affiliation................. 33

a. In Fact, Party Affiliation Does Not

Explain Why Blacks are Not Elected

as District Judges in Harris

County............................. 3 3

b. As a Matter of Law, the Defendants'

Contentions are Inaccurate ........ 36

2. Appellants' Claims Regarding the Role of

Bar Polls, Endorsements and Similar

Factors Is Irrelevant as a Matter of Law 37

3. The District Court Properly Limited its

Review to Elections Involving Black and

White Candidates.......................38

4. The District Court Properly Found that

the Underlying Data Set Used by the

Experts for the Plaintiff-intervenors

vi

and the Defendants in Harris County

is Reliable............................. 39

III. The District Court Properly Assessed Minority

Electoral Success in Harris County District

Judge Elections................................ 4 0

CONCLUSION..................................................42

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, N.C., 470 U.S.

564 (1985)....................................... 27

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385, 404 (1986)......... 37

Brewer v. Ham, 876 F.2d 448, 452 (5th Cir. 1989)..... 19

Brooks v. Georgia State Board of Elections, Civ. Ac.

No. 288-146 (S.D. Ga. Dec. 1, 1989)......... 23, 26

Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d 141 (2d Cir.

1985), cert, denied. 478 U.S. 1021 (1986) ..... 23

Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240, (5th Cir.

1988), cert, denied, 109 S.Ct.

3213 (1989) ........ 19, 20, 21, 27, 28, 30, 31, 38

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1988)................................... 19, 22, 23

. Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna, 834

F.2d 496, 504 (5th Cir. 1987), cert denied,

109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989)............... 26, 27, 30, 31

City of Carrollton Branch of the NAACP v. Stallings, 829

F.2d 1547 (11th Cir. 1987) cert, denied

108 S.Ct. 1111 (1988)................ ............ 24

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S.

102 L. Ed.2d 854 (1989)................

Clark v. Edwards, Civ. Ac. No 88-435-A

(Aug. 31, 1988).........................

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 831 F.2d 246

(11th Cir. 1987)........................

40

23

23

Gingles v. Edminsten, 590 F. Supp. (E.D.N.C. 1984)....28

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987)..23

SCLC v. Siegelman, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala.

1989)........................................ 23, 24

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944).............. 36

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) 3, 4, 6, 10,

................. 19, 20,21, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 34

Un. Latin Amer. Cit. v. Midland Ind. Sch. Dist,'

viii

812 F.2d 1494 (5th Cir. 1987), vacated on other

grounds. 829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987)........... 30

Wards Cove Packing Company, Inc. v. Atonio,

104 L. Ed.2d (1989)..................

490 U.S. ____,

......... 40

Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City

of Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201

(5th Cir. 1989)........................ 20, 27, 31

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971).......... 34, 35

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

Art. 5, Section 7 (a)i of the Texas Constitution..... 18

42 U.S.C. § 14 (C) (1) (1973) ..........................22

42 U.S.C. §1973 ....................................... 1

Rule 52(a)............................................ 38

S.Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong.

2d Sess. 28-9 (1982)........ 12, 14, 20, 31, 32, 36

28 U.S.C. § 1291,.................................. viii

Title VII,........................................... 41

Voting Rights Act of 1965......................1, 11, 35

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This Court's jurisdiction is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §

1291. The district court entered judgment in favor of all

plaintiffs on November 14, 1989 and issued an injunction on January

11, 1990. Defendant-appellants filed notices of appeal on January

11, 1990.

x

(1) Whether the district court's holding that district judge

elections in Harris County, Texas violate Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, is clearly erroneous

and should be reversed?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiff-intervenors in this case are Black registered

voters residing in Harris County, Texas, and the Houston Lawyers'

Association ("HLA plaintiff-intervenors") an organization of Black

attorneys based in Houston. They contend that the at large system

of electing district judges in Harris County denies Black voters

the opportunity to elect the candidates of their choice to the

state district judiciary, in violation of section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973.

HLA plaintiff-intervenors incorporate the Statement of the

Case set out in the Brief of the State Appellants, with respect to

the "Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court Below"

only. The HLA plaintif f-intervenors set out the Statement of Facts

below.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I. Introduction

District judges in Texas are elected in at large elections

from areas, which in accordance with the Texas Constitution as

amended in 1985, may be no smaller than an entire county. Slip

Op. at 7. District judges have jurisdiction over cases arising

1

anywhere in the county, and venue over each case is countywide.

District judges are therefore accountable to every citizen of the

county. TR. at 5-78. Because district judges are elected from the

entire county rather than from geographic subdistricts within the

county, the system for electing district judges in Texas, is an at

large system. Slip Op. at 7, n.3.

Harris County, with a total population of 2,409,544, is the

largest county by population in the State of Texas. Slip Op. at

14. Although Blacks comprise 19.7% of the total population, and

18.2% of the voting age population in Harris County, id., only

three of the 59 district judges (or 5.1%) currently serving Harris

County are Black. TR. at 4-262. Since 1980, only 2 of the 17

Blacks who have run for District judge in Harris County in

contested elections have been elected. Slip Op. at 73.

District court judges must be nominated in a primary election

by a majority of the votes cast. Slip Op. at 7. Each candidate's

political party is indicated on the ballot. Id. District judges

run for specifically numbered judicial seats. This is the

equivalent to a numbered post system, which prevents the use of

bullet, or single shot voting.1 Slip Op. at 71 n.31.

Candidates for District judge must be citizens of the United

States and the State of Texas, licensed to practice law in this

State and a practicing lawyer or Judge of a court in Texas, or both *

"Single-shot voting enables a minority group to win some

at-large seats if it concentrates its vote behind a limited number

of candidates and if the vote of the majority is divided among a

number of candidates." Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 38 n.

5 quoting City of Rome v. United States. 446 U.S. 156, 184 n. 19

(1980).

2

combined for four years. Slip Op. at 7. Candidates must have been

a resident of the county from which they run for at least two years

and reside in that county during their term of election. Id.

District courts in Harris County have been organized by

informal arrangements into four specialized areas: civil trial

courts, criminal trial courts, juvenile courts and family law

courts. See Deposition Summary of Ray Hardy, TR. at 4-254. Of the

three Blacks who currently serve as district judges in Harris

County, two are criminal trial court judges, and one is a family

law judge. No Black has ever been elected to a civil district

trial seat. TR. at 3-207.

II. Facts Related to the "Ginoles Factors"

In Thornburg v. Ginales. 478 U.S. 30 (1986), the Supreme

Court identified three critical elements of a section 2 challenge

to the use of at large election districts:

First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate

that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact

to constitute a majority in a single-member

district...Second, the minority group must be able to

show that it is politically cohesive...Third, the

minority must be able to demonstrate that the white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it — in

the absence of special circumstances, such as the

minority candidate running unopposed,...— usually to

defeat the minority's preferred candidate. Ginales. 478

U.S. at 50-51.

The district court's findings relevant to the three-pronged test

in Thornburg v. Ginales. 478 U.S. 30 (1986) (hereinafter "Ginales")

3

are set out below.

A. Blacks in Harris County Are Sufficiently Numerous and

Geographically Compact to Constitute a Majority

in a Single Member District

The district court found that Black residents in Harris County

are concentrated in the North Central, Central and South Central

areas of the county, and found that it is possible to create

majority Black single-member districts. Slip Op. at 15. HLA

plaintiff-intervenors' expert, Mr. Jerry Wilson, showed that

thirteen such electoral districts could be drawn.2 TR. at 3-229-

233; See also HLA plaintiff-intervenors' Exhibit 2, 2(a). His

testimony was not disputed at trial.3

Mr. Wilson testified that Blacks in Harris County live in

highly concentrated majority Black areas, particularly in the City

of Houston. In fact, Mr. Wilson's demographic analysis revealed

that nearly 80% of all Blacks live in 94 majority Black Census

tracts in Harris County. TR. at 3-235-236. Several lay witnesses

also testified that Harris County has traditionally been and

continues to be, residentially segregated. See. Deposition Summary

of Judge Thomas Routt, TR. at 3-207; Testimony of Weldon Berry, TR.

at 4-16-17.

2 The LULAC plaintiffs introduced undisputed evidence at

trial that at least nine single member electoral districts with a

majority Black voting age population could be drawn in Harris

County. Slip Op. at 15.

Although the district court recognized that the concept

of "one person, one vote" does not apply to judicial electoral

districts (Slip Op. at 15) , both the illustrative single-member

district plans submitted by the plaintiffs and the plaintiff-

intervenors for Harris County contemplated the creation of "ideal

districts" of approximately equal populations in accordance with

the "one person, one vote" principle. See. Slip Op. at 15.

4

No evidence was introduced at trial to rebut the testimony of

either the expert or lay witnesses for the HLA plaintiff-

intervenors, that Blacks in Harris County are sufficiently large

and geographically compact so as to constitute a majority in a

single member district.

B. Blacks in Harris County are Politically Cohesive

Based on the uncontradicted evidence introduced at trial, the

district court found that Blacks in Harris County are politically

cohesive. This finding was based on the results of the election

analyses of experts for both the HLA plaintiff-intervenors and the

defendants. In crediting the conclusions reached by the HLA

plaintiff-intervenors' expert, that voting in Harris County is

racially polarized and that Blacks are politically cohesive, the

Court noted that an inquiry into racially polarized voting helps

ascertain whether the minority group members challenging an

electoral scheme are politically cohesive. Slip Op. at 22, quoting

Ginoles. The Court's findings on the existence of racially

polarized voting will be discussed at length below.

In concluding that Blacks in Harris County are politically

cohesive, the district court additionally relied on the credible

testimony of Black former district judge candidates and prominent

members of the Harris County Black community. Slip Op. at 30. The

court specifically credited the lay testimony of witnesses Sheila

Jackson Lee, Thomas Routt, Weldon Berry, Francis Williams and

Bonnie Fitch, who testified about their experiences as candidates

and voters in Harris County. Id.

5

No evidence was introduced at trial to contradict the

testimony of these witnesses. In fact, expert witnesses for the

defendant and defendant-intervenors also testified that Black

voters in Harris County are politically cohesive. See. TR. at 5-

268.

C. Whites Sufficiently Vote as a Bloc vote in Harris

County District Judge Elections so as to Defeat the

Candidates of Choice of Black Voters

The district court found that "the Anglo of white bloc vote

in Harris County is sufficiently strong to generally defeat the

choice of the Black community." Slip Op. at 30. This finding was

based on the testimony of all of the experts. Slip Op. at 22-

32 .

"Statistical analyses are the common methodology employed and

accepted to prove the existence of political cohesiveness apd’

racial bloc voting necessary to establish a voter dilution case."

Slip Op. at 7-8. The Court found the statistical evidence

presented by the HLA plaintiff-intervenors in Harris County to be

"legally competent and highly probative." Slip Op. at 87.

1. The Virtual Refusal of White Voters to Support

Black Candidates

HLA plaintiff-intervenors1 expert, Dr. Richard Engstrom, whose

work on quantitative analyses was cited with approval by the

Supreme Court in Ginoles. 478 U.S. at 53, n. 20, performed both

homogenous precinct analysis and bivariate ecological regression

analysis on the seventeen (17) contested district judge general

elections in which a Black candidate faced a White opponent since

6

1980.4 Dr. Delbert Taebel, expert for the defendant-intervenors,

analyzed 23 district judge elections and 11 county court at law

elections in Harris County. The elections analyzed by Dr. Taebel

included elections in which Hispanic candidates ran against White

opponents,5 unopposed elections, and elections in which both

candidates were White. In accordance with the law of this Circuit,

the district court found that "unopposed election contests and

White versus White contents [we]re not germane" to its analysis of

White bloc voting. Slip Op. at 81.

Despite the differences in the elections analyzed by the

experts for the HLA plaintiff-intervenors and the defendant-

intervenors, the results of both experts' analyses were strikingly

4 Dr. Engstrom did not analyze primary elections, because

primary elections do not involve the entire electorate in Harris

County (TR. at 3-72; 130), and have not been the filter for the

candidate of choice of Black voters in Harris County. TR. at 3-

130-132. See also 5-260. The district court credited Dr.

Engstrom's testimony in this regard. Slip Op. at 27.

Defendant-intervenor Wood attacked Dr. Engstrom's

analysis on the ground that his data did not allocate absentee

votes and did not include the Asian-American population in Harris

County. Dr. Engstrom testified that absentee votes are not

allocated by precinct in Harris County, and that in any case,

absentee votes never rose above 10% prior to 1988 (in 1988 absentee

votes in judicial elections rose to approximately 13.6% per

precinct, Slip Op. at 27). Furthermore, Dr. Engstrom testified

that Asian-Americans are included in the non-Black population

indicated in his homogenous precinct analysis. See Slip Op. at 96-

97, Appendix A. Defendant-intervenor Wood presented no evidence

indicating the size of the Asian-American population in Harris

County, or its impact on voting. The district court found that Dr.

Engstrom adequately addressed defendant-intervenor Wood's concerns.

Slip Op. at 27.

No claims on behalf of Hispanic voters in Harris County

were advanced by LULAC plaintiffs or by the HLA plaintiff-

intervenors in this action.

7

similar.6 Blacks and Whites voted differently in every election

analyzed by both Dr. Engstrom and Dr. Taebel. Slip Op. at 32.

The district court found that Dr. Engstrom's regression

analysis showed a strong relationship between race and voting

patterns in Harris County. Slip Op. at 23. In 16 of the 17

outcome determinative elections analyzed by Dr. Engstrom, Black

voters supported the Black candidate. See. Slip Op. at 96-97,

Appendix A. In each of those elections, the candidate supported

by Black voters lost. See. Slip Op. at 98-100. Dr. Engstrom

testified that the probability that these election outcomes

occurred by chance were less than 1 in 10,000. Slip Op. at 24.

The district court found that Dr. Engstrom's homogenous precinct

analysis corroborated the results of his regression analysis. Slip

Op. at 26. It showed that Black voters in Harris County gave more

than 96% of their votes to the Black candidate in 16 ' of 17

elections. Slip Op. at 26.

Lay testimony from witnesses for the HLA plaintiff-

intervenors supported the conclusions of Dr. Engstrom. Judge

Thomas Routt7, one of the three currently sitting Black district

judges in Harris County, testified that in district judge elections

Both HLA plaintiff-intervenors' and defendant-

intervenors1 experts used the same underlying data set to perform

their statistical analyses. This data set, provided by Dr. Richard

Murray, a University of Houston political scientist provided an

estimation of the ethnic make-up of the electoral precincts in

Harris County from 1982 to 1988. Defendant-intervenors raised

questions as to the authenticity and accuracy of this data, see

Brief of Defendant-intervenor Wood at 7, n.7, even though their

own expert Dr. Taebel used the same data for his analysis, and at

trial personally vouched for both the authenticity and reliability

of Dr. Murray's data. TR. at 5-276-277.

Judge Routt was called as witness for deposition by

defendant-intervenor Wood.

8

in which a Black candidate faces a White opponent, Blacks will vote

for the Black candidate and Whites will vote for the White

candidate. See. Deposition Summary of Thomas Routt, TR. at 3-206.

2. The Irrelevance of Party Affiliation

The defendants contended that the absolute disparity in Black

and White voting and candidate success patterns should be ascribed

to party affiliation. This issue was fully ventilated at trial and

rejected by the district court.

Judge Mark Davidson, a sitting district judge from Harris County

first elected in 1988, who is White, testified that he analyzes the

results of judicial elections as a hobby’.8 Slip Op. at 30. He

conceded that voting in Harris County is racially polarized,

however he contended that political party and not race determines

the outcome of elections* in Harris County. TR. at 3-318.9 Dr.

Taebel also testified that voting in Harris County is racially

polarized, but attributed the loss of Black candidates to partisan

politics. TR. at 5-268.

HLA plaintiff-intervenors' expert Dr. Engstrom testified

however, that even when elections results within one party are

Judge Davidson testified for defendant-intervenor Wood

as an expert.

Judge Davidson identified Blacks as straight ticket

Democratic voters. He identified both Republican voters and swing

voters as white. TR. at 3-331; 338. Judge Davidson testified that

white swing voters control the outcome of elections in Harris

County. TR. at 3-338.

9

analyzed, a gross disparity exists between the success rates of

White and Black candidates. For instance, since 1980, 52% of White

Democratic candidates have won contested district judge elections,

while only 12.5 % of Black Democratic candidates have been

successful in District judge elections. TR. at 3-134-135. It was

further revealed through both lay and expert testimony that even

in years in which the defendants contend Democratic or Republican

candidates were "swept" into office by a straight top of the

ticket vote, Black candidates from the prevailing political party

persistently fared worse than their White counterparts. TR. at 3-

139. In 1986 for example, Gov. Mark White, a Democratic candidate

at the top of the ticket, won the majority of the vote in Harris

County.10 * Every White Democratic incumbent judge wae reelected.

However, every Black Democratic incumbent judge lost his or her

reelection bid.11 Tr*. at 3-164. See also. Slip Op. at 98-100,

9

Appendix A. Dr. Engstrom concluded that race, not party, is the

primary determinant of the outcome of district judge elections in

Harris County. TR. at 3-140.

The district court was unpersuaded by the defendants' claim

that partisan preference and not race best explains the outcome of

district judge elections in Harris County. Instead, the Court

In this general election, Democrats won 14 of the 20

contested countywide judicial seats up for election. TR. at 3-

139.

Two of the incumbent Black judges, Francis Williams and

Bonnie Fitch, were county court at law judges. Weldon Berry was

the incumbent district judge. Although defendants contended that

the Black incumbents had been in office for relatively shorter

periods of time than their white incumbent counterparts and thus

lacked comparable name recognition, Judge Berry had been in office

for a year and one half, almost the entire term. TR. at 4-15. All

three Black incumbents had been appointed to office.

10

found that once plaintiffs, as in this case, have proved the first

two prongs of the Ginqles test, and the Senate factors point to

vote dilution, it is unimportant whether a White bloc vote, which

is sufficient usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidate

is made up of Democrats or Republicans. Slip Op. at 79-80.

The district court was similarly unpersuaded by defendant-

intervenor Wood's claim that in those elections in which partisan

voting could not explain the loss of Black candidates, bad

publicity, failure to win the Houston Bar Association Preference

Poll12, or failure to obtain the endorsement of the Gay Political

Caucus ("GPC") explained the loss of Black candidates. Slip Op.

at 31. Dr. Taebel, expert for the defendants, conceded at trial

that attempting to analyze the role campaign expenditures,

incumbency and Bar Poll results had on whether a candidate won or

lost would be an impossible task. TR. at 5-274.

II. Senate Report Factors

The Senate Report that accompanied the 1982 amendments to

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act identified nine "[t]ypical

factors" which tend to establish a vote dilution claim.13 S.Rep. * 1

In 1986, the year of the Democratic near sweep, Frances

Williams, a Black Democratic appointed incumbent county court at

law judge, won the Houston Bar Association preference poll, but

still failed in his reelection bid, along with the two other Black

Democratic incumbent candidates.

v3 "Typical factors include:

1. the extent of any history of official discrimination in

the state or political subdivision that touched the right of the

11

No. 97-417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982) (hereinafter "Senate

Report") .14

The court below found that an analysis of "the Senate Factors

applicable to the present case point to the continual effects of

members of the minority group to register, to vote, or otherwise

to participate in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the elections of the state

or political subdivision is racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or political subdivision

has used unusually large election districts, majority vote

requirements, anti-single shot provisions, or other voting

practices or procedures that may enhance the opportunity for

discrimination against the minority group;

4. if there is a candidate slating process, whether the

members of the minority group have been denied access to that

process;

5. the extent to which members of the minority group in the

state or political subdivision bear the effects of discrimination

in such areas as education, employment and health, which hinder

their ability to participate effectively in the political process;

•

6. whether political campaigns have been characterized by

over or subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of the minority group have

been elected to public office in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases have had probative value

as part of plaintiff's evidence to establish a violation are:

whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness on

the part of elected officials to the particularized needs of

the members of the minority group.

whether the policy underlying the state or political

subdivision's use of such voting qualification, prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice or procedure is tenuous."

S. Rep. at 28-29.

Congress did not intend that these factors be used as a

mechanical "point counting" device. S. Rep. at 29, n. 118.

Therefore, only those Senate factors relevant to this case will be

discussed in this section.

The Supreme Court has specifically recognized the Senate

Report as the "authoritative source for legislative intent" in

interpreting amended section 2. Ginales. 478 U.S. at 43, n.7.

12

historical discrimination hindering the ability of minorities to

participate in the political process." Slip Op. at 79. The Court

also detailed specific findings related to each Senate Factor,

discussed below.

A. History of Discrimination and Depressed

Socioeconomic Status

The district court, citing a long line of cases from this

Circuit dating from 1974 to the present, found that the history of

discrimination against Blacks in the areas of education, employment

and health in all of the counties at issue in this case "is either

well chronicled or undisputed." Slip Op. at 69-70. The Court

further found that this history of discrimination adversely

affected the socioeconomic condition of Blacks in the challenged

counties and inhibited their ability to participate in the

democratic system governing the State of Texas. Slip Op. at 70.

This finding was supported by evidence of stark socioeconomic

disparities between Blacks and Whites residing in Harris County.

See Plaintiffs' Exhibit H-08.

Lay witnesses for the HLA plaintiff-intervenors also testified

that Harris County has a history of discrimination that continues

to effect rights of Blacks today. One witness, Judge Thomas Routt,

one of the three currently sitting Black district judges in Harris

County, testified that there is more racial prejudice today in the

County than when he first sought judicial office during the 1970's.

See. Deposition Summary of Thomas Routt, TR. at 205. Francis

Williams, a Black former appointed County Court at Law judge

testified that when he first began practicing law in 1951, the

Houston Bar Association refused to admit Blacks. See, Deposition

13

Summary of Francis Williams, TR. at 3-217. This prohibition,

according to Mr. Williams, was part of the Houston Bar

Association's Constitution. Id. See also. Testimony of Weldon

Berry, TR. at 4-8 ;4-16-17;4-24-25.

B. Racial Polarization in Voting

The district court's findings on the existence of racially

polarized voting in Harris County district judge elections have

been discussed at length above.

C. The Use of "Enhancing" Devices

The Senate Report specifically identifies unusually large

elections districts, majority vote requirements and anti-single

shot provisions^ as practices which "may enhance the opportunity

for discrimination against the minority group". S. Rep. at 29.

The district court found that each of these practices are part of

the district judge electoral scheme in Harris County, Texas. Slip

Op. at 71-72.

The Court found that the requirement that district judge

candidates run for a specific numbered judicial seat within the

county, is equivalent to a numbered post system, which prevents

the use of bullet, or single shot, voting. Slip Op. at 71; 71, n.

31. The Court further found that in order to win the party primary

a candidate for district judge must win a majority of the votes

cast.15 Id.

The Eighth Circuit recently held that a majority

vote/primary run-off requirement for municipal elections in

Phillips County, Arkansas violates section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act. See, Whitfield v. Clinton. Civ. Ac. No. 88-1953 (8th Cir.

14

Finally, the court found that the unusually large size of

Harris County "further enhance[s] the problems that minority

candidates face when they seek office." Slip Op. at 72. Thomas

Phillips, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas, testified

that it is more difficult for minority lawyers to raise the funds

necessary to a mount a successful campaign for district judge in

large urban areas, such as Harris County. TR. at 5-84.

D. Racial Appeals

The court below made no findings regarding the use of racial

appeals in judicial campaigns in Harris County. However, several

witnesses testified that race continues to play a prominent role

in judicial campaigns in Harris County.16

Dec. 7, 1989).

Former appointed county court at law judge Bonnie Fitch-,

for example, testified that she vas the victim of racial appeals

in both her 1986 and her 1988 judicial election bids. In 1988, Ms.

Fitch testified that her opponent published literature with her

picture on it. See. Deposition Summary of Bonnie Fitch, TR. at 3-

209. Ms. Fitch also testified that she received a call from a

female voter who wanted to know if the fair-skinned Ms. Fitch were

Black or White, because, as this voter explained, she could not

vote for a Black person. Id. at 3-211. Ms. Fitch also noted that

of the nineteen Democratic incumbent judges who appeared in a group

photograph on campaign literature in 1986, only the three Blacks

who appeared in the picture failed to win their reelection bids.

Id. at TR. 3-209.

Harris County district judge Thomas Routt testified that his

name assisted him in his election bid, because it does not sound

like a typical Black name. See. Deposition Summary of Thomas

Routt, TR. at 3-206. According to Judge Routt, names which can be

clearly identified as minority names can work against a candidate.

Id. at 3-207.

Similarly former appointed district judge Weldon Berry

testified that Black candidates enjoy greater electoral success if

they are not racially identifiable during the campaign. TR. at 4-

21. Former judge Berry specifically pointed to the successful

campaign of judge Ken Hoyt, who withheld his photograph from

certain Republican party campaign literature during his campaign

for judge on the Civil Court of Appeals. TR. at 4-21.

15

F. Minority Electoral Success

Although Blacks make up 19.7% of the total population, and

18.2% of the voting age population in Harris County, only 3 of

Harris County's 59 district judges (or 5.1%) are Black. Slip Op.

at — . It was undisputed that no more than three Blacks have ever

served as district judge at the same time in Harris County. See.

Deposition Summary of Thomas Routt, TR. at 3-207.

The defendants and defendant-intervenors argued that the

appropriate reference point for evaluating the extent of Black

electoral success in Harris County however, is the eligible pool

of minority lawyers, rather than eligible minority voters.17

The district court found that the appropriate reference for

calculating minority electoral success in voting rights cases is

eligible minority voters, Slip Op. at 74-75, noting that even if.

there is a relationship between the number of minority judges and

the number of eligible minority lawyers, "that fact does not

explain why well qualified eligible minority lawyers lose judicial

elections." Slip Op. at 75.

The district court also found that only 2 of the seventeen

Black candidates (or 12%) who ran in contested district judge

general elections in Harris County since 1980 won. Slip Op. at

73. The district court found that in the primary elections

In support of this contention, the defendants offered the

testimony of expert James Alan Dyer, who conducted a poll to

determine the number of Black attorneys in Harris County who are

eligible to serve as district judges. Despite the defendants'

contention that the small number of minority judges is related to

the small number of Black eligible attorneys, the poll commissioned

by the defendants' revealed that there are over 500 qualified Black

attorneys residing in Harris County, who are eligible to serve as

district judges. See Defendants' Exhibit D-4, Table Four.

16

analyzed by the defendants' expert, the Black preferred candidate

won six of the nine primaries, but each Black preferred candidate

who won the primary, lost the general election. Slip Op. at 32.

17

G. Tenuousness

Chief Justice Thomas Phillips, a defendant in this action,

testified at trial that Art. 5, Section 7 (a)i of the Texas

Constitution was enacted in 1985 as part of a broader effort to

equalize the dockets of district judges. TR. at 5-78. Judicial

caseload is dependent on the number of cases before the judge and

not the size of the district. Justice Phillips was unable to

explain how mandating a countywide election system would further

the stated goal of equalizing judicial dockets.

Although the district court did not find that the current at

large system of electing district judges was a tenuously based

pretext for intentional discrimination, it was "not persuaded that

the reasons offered for its continuation are compelling." Slip Op.

at 77.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The district court properly held that the at-large method of

electing district judges in Harris County, Texas violates section

2 of the Voting Rights Act in that it denies Black voters an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process and elect

candidates of their choice to the Texas judiciary. The court's

findings were not clearly erroneous.

In evaluating a section 2 claim, plaintiffs are required to

make a three-part threshold showing. Thornburg v. Gingles. 478

U.S 30, 50-51 (1986). See also. Brewer v. Ham. 876 F.2d 448, 452

(5th Cir. 1989); Campos v. City of Baytown. 840 F.2d 1240, 1244

(5th Cir. 1988), cert. denied, 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989). HLA

plaintiff-intervenors satisfied this three-pronged test by showing:

18

that the Black population in Harris County is sufficiently large

and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a fairly

drawn single-member judicial district; that Blacks in Harris County

are politically cohesive; and that Whites in Harris County vote

sufficiently as a bloc so as to usually defeat the candidate of

choice of Black voters, absent special circumstances.

The district court did not err in finding that voting in

Harris County is racially polarized in district judge elections.

The court's findings are well supported by the record in this case.

Racially polarized voting is usually proven by statistical evidence

of racial voting patterns in relevant elections. Campos. 840 F.2d

at 1243. In the instant case, the district court relied on

overwhelming statistical evidence which showed that Black voters

are politically cohesive. The statistical evidence showed that

Black and White voters vote differently in elections involving

Black and White candidates: White voters support the white

candidate, and Black voters support the Black candidate. This

polarization results in a pattern of loss for Black candidates in

Black on White judicial election contests.

Elections involving Black and White candidates are most

probative of racially polarized voting. Westweqo Citizens for

Better Government v. City of Westweao. 872 F.2d 1201, 1208 n. 7

(5th Cir. 1989) . The district court properly accorded great weight

to the results of these elections.

The Voting Rights Act requires a court to look at the totality

of the circumstances in evaluating a section 2 claim. Once a

plaintiff meets the Gincles three-pronged test, impermissible vote

dilution is shown. Evidence of the objective Senate Report Factors

19

buttresses the plaintiffs' showing that a section 2 violation

exists. Plaintiffs are not required to prove all of the Senate

Factors, nor should the Senate Factors be used as a mechanical

point-counting device. S. Rep. at 29 n. 118. With regard to the

Senate Factors, the court below found that: Texas and Harris

County have a history of discrimination that continues to effect

the socioeconomic condition of Blacks; voting in Harris County is

racially polarized; district judge elections in Texas are

characterized by three devices, including a numbered post system

which tend to enhance the opportunity for discrimination against

minority groups; and Blacks have enjoyed little electoral success

in district judge elections in Harris County. The court's findings

regarding Black electoral success in Harris County were properly

based on the eligible Black voter population.

The court below properly concluded that race, not party is the

primary determinant of election outcomes in judicial elections in

Harris County. This Circuit follows the view that the reasons why

white voters refuse to support Black candidates is irrelevant to

a section 2 inquiry. See. e.a .. Campos, 840 F.2d. 1240 (5th Cir.

1988) . Claims of non-racial reasons for the loss of Black

candidates are entitled to little probative weight once, as in this

case, plaintiffs have satisfied the three-pronged Ginqles test and

the Senate Report factors point toward the existence of vote

dilution.

20

ARGUMENT

I. The Defendants Attempt to Distinguish Harris County

Judicial Elections From Those Elections to Which

Section 2 Apply, Rests on Fundamentally Erroneous Factual

and Legal Arguments

A. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to

elected trial judges

The defendants argue that this Circuit's decision in Chisom

was limited to elections for appellate court judges, or judges who

sit, like legislators, on collegial decisionmaking bodies. See,

Brief of Defendant-Appellees at 17-18. Nothing in this Circuit's

decision in Chisom supports the defendants' strained

interpretation. See. Chisom v. Edwards. 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1988) , rehearing and rehearing en banc denied, Chisom v. Roemer

853 F. 2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied, 102 L. Ed.2d 379

(1988) .

Chisom follows the example set by the Supreme Court of giving

the Voting Rights Act "'the broadest possible scope' in combatting

racial discrimination." Chisom. 839 F.2d 1056, 1059. In

interpreting the scope of the Voting Rights Act, this Circuit

correctly focused on its plain language, which states that its

provisions are meant to include voting in "any primary, special,

or general election... with respect to candidates for public or

party office..." Chisom. 839 F.2d at 1060, quoting 42 U.S.C. § 18

18 Chief Justice Phillips testified that district judges in

Texas, in fact, do engage in some collegial decision-making in

administrative areas such as: choosing county auditors;

promulgating local rules of procedure; assigning jury panels; and

deciding how a jury panel is to be drawn. TR. at 5-81.

21

1973 1 (c)(1)(1965). "Nowhere in the language of Section 2 nor in

the legislative history does Congress condition the applicability

of Section 2 on the function performed by an elected official."

Dillard v. Crenshaw. 831 F.2d 246, 250 (11th Cir. 1987).

The Chisom panel specifically acknowledged the difference

between the "representative" functions performed by legislators,

and the role of judges in administering the law, but adopted the

view of the Martin v. Allain court that "Section 2 is not

restricted to legislative representatives but denotes anyone

selected or chosen by popular election from among a field of

candidates... including judges". 839 F.2d at 1063, quoting Martin

v. Allain. 658 F. Supp 1183 , 1200 (S.D. Miss. 1987). This court

never suggested that any rationale exists for limiting the scope

of Section 2 to only certain kinds of elected judges. In fact,,

the Chisom court's reliance on Martin. a challenge to the at large

election of circuit and chancery trial judges in Mississippi,

indicates that this Circuit recognized the application of Section

2 to the election of trial judges.

Section 2 has been applied to the election of trial judges in

challenges throughout the country. Clark v. Edwards, Civ. Ac. No.

88-435-A (M.D. La. Aug. 31, 1988); Brooks v. Georgia State Board

of Elections. Civ. Ac. No. 288-146 (S.D. Ga. Dec. 1, 1989), SCLC

v. Siegelman. 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989)

B. District Judges in Harris County are Elected

At-Large

The defendants contend that each numbered post within the

countywide election district in Texas is, in essence, its own

22

single member district. See Brief of State Defendants at 17-20;

Brief of Defendant-intervenor Wood at 22-24. This characterization

of the Texas judicial electoral scheme is blatantly wrong. As the

District Court found, the requirement that district judges in Texas

run for a specific numbered seat within the countywide or multi

county district "is the equivalent of a numbered post system"

which prevents the use of bullet, or single shot, voting. Slip Op.

at 71.

Judges in multijudge districts and circuits do not hold

single-member offices. SCLC v. Sieqelman, 714 F. Supp. 511

(M.D.Ala. 1989). A single-member office is one in which "only one

individual hold[s] [the] office in the geographic area, i.e., ...

there is only one such office in the particular jurisdiction." Id.

at 518 n. 17. By contrast, fifty-nine (59) judges are elected to

serve within Harris County. Although candidates are required to

run for a numbered judicial post, e.q., "152nd Civil District

Court," these numbers do not correspond to different geographical

areas of election or jurisdiction, nor do they correspond to

different judicial offices in which unique duties are performed.19

19 As defendant-intervenor Wood points out, "each judge is

elected by...every citizen in the county;...each judge has

jurisdiction over cases arising anywhere in the county;...venue

over each case is county-wide..." Brief of Defendant-intervenor

Wood at 22.

The defendant's reliance on the Second Circuit's decision in

Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d 141 (2d Cir. 1985) , cert.

denied. 478 U.S. 1021 (1986) is also misguided. In Butts,

plaintiffs challenged New York City's 40%vote/primary run-off

requirement for single—member officers elected citywide. The

offices at issue — mayor, city council president and comptroller -

- were single person offices. Only one person was elected to each

office, and each officer performed unique duties particular to that

office only. As discussed above, district judges in Harris County

23

The same group of voters elects judges to every numbered district

court in the county. "[Bjecause judges are elected from the entire

county rather than from geographic subdistricts within the county,"

this is an at large election system. Slip Op. at 7 n.3.

Texas' numbered post method of electing district judges

therefore, enhances the dilutive nature of the at large election

scheme. The use of an "enhancing device" specifically identified

in the Senate Report, like a numbered post system, cannot be used

as defense in a vote dilution case. The numbered post, at large

scheme for electing district judges in Texas, is similar to the

system of electing superior court judges in the state of Georgia,

where state officials were recently ordered by a federal court to

preclear all past changes in judicial elections in accordance with

Section 5 of, the Voting Rights Act. In that case, the court

described Georgia's numbered post judicial electoral scheme as

"hav[ing] the potential for discrimination. Where

more than one judicial post exists in a given circuit,

these election rules require a candidate to run for

a specific seat. Georgia law thus precludes the

alternative system where all candidates compete against

each other and where judgeships are awarded to the

highest vote-getters out of the field of candidates.

One effect of precluding the latter form of

election is to prevent effective 'single-shot' voting.

In a 'single-shot' campaign, a cohesive bloc of

minority voters agrees to vote for only one candidate

out of a group of candidates running for office, even

though two or more office holders will be elected out

of the group of candidates running.

do not perform unique functions. Moreover, some courts have

recently applied section 2 to single—member offices. See e. c. ,

City of Carrollton Branch of the NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d 1547

(11th Cir. 1987) (applying Section 2 to election for single-member

county commission) , cert. denied 108 S.Ct. 1111 (1988) ; Dillard v.

Crenshaw Countv. 831 F.2d 246, 250 (11th Cir. 1987) (applying

Section 2 to election for chairman of county commission).

24

Brooks v. Georgia State Board of Elections. Civ. Ac. No. 288-146,

(S.D. Ga. Dec. 1, 1989) Slip Op. at 16. The system for electing

district judges in Harris County has the same effect.

II. The District Court Correctly Applied the Totality of

the Circumstances Test as Described in Ginqles

"The clearly-erroneous test of Rule 52(a) is the appropriate

standard for appellate review of a finding of vote dilution".

Ginales. 478 U.S. at 79. Trial courts evaluating a statutory claim

of vote dilution engage in an intensely factual inquiry, based

"upon a searching practical evaluation of the 'past and present

reality'". Id. The reviewing court therefore, must defer to the

local district judge's "particular familiarity with the indigenous

political reality" of the State. Id. See also Citizens for_a

Better Gretna v. City of Gretna. 834 F.2d 496, 504 (5th Cir. 1987)

(recognizing district court's familiarity with political realities

of local area).

The defendants challenging the district court's finding of

vote dilution bear a heavy burden of showing that the district

court made fundamental legal and factual errors. It is not enough

that the defendants, or even this court, would have found the facts

differently. This court remains bound by the clearly erroneous

standard. Under this standard, this court may rule that the

district court's findings are clearly erroneous only if " on th

entire evidence [this court] is left with the definite and firm

25

Campos v. City ofconviction that a mistake has been committed."

Bavtovn. 840 F.2d at 1243, quoting Anderson v. City of Bessemer

Citv. N.C. . 470 US 564, 573 (1985). Nothing in the district

court's opinion in this case, is clearly erroneous.

The district court, in the case at hand, properly applied the

"totality of the circumstances" test. The court's 94 page opinion,

reflects a careful review of the typical objective factors

enumerated in the Senate Report, and a proper application of the

three-pronged Ginales analysis to Texas' district judge electoral

scheme. The court correctly concluded, as a result of this

analysis, that the at large system of electing district judges in

Harris County, Texas denies Black voters an equal opportunity to

elect the candidates of their choice to the judiciary.

A. The District Court Applied the Correct Standards to

its Analysis of White Bloc Voting in Harris

Countv ______________________________ ____

1. The Standard for Interpreting Statistical

Analyses of Racially Polarized Voting

Racially polarized voting "is the linchpin of a section 2 vote

dilution claim. Westweqo Citzens for a Better Government v. City

of Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201, 1207 (5th Cir. 1989) quoting Citizens

for a Better Gretna v. Citv of Gretna. 834 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir.

1987), cert denied. 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989). Ginales and this

Circuit's post-Gingles decisions20 have set out well-defined

20 See, Campos v. Citv of Bavtown. 840 F.2d 1240; Westwego

Citizens for Better Government v. Citv of Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201

(5th Cir. 1989) ; Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna,

834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987), cert denied, 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989).

26

standards for determining the existence of racial bloc voting,

which is "usually proven by statistical evidence." Campos v. City

of Bavtown. 840 F.2d 1240, 1243 (5th Cir. 1988).

In Ginoles. the court reviewed election analyses prepared by

the expert for the appellees which to showed the racial differences

in candidate preferences among white and Black voters in the

challenged North Carolina jurisdiction. The experts in Gingles

employed two complementary methods of analysis which are standard

in the literature for the analysis of racially polarized voting.

Gingles, 478 U.S. at 53 n. 20, citing Gingles v. Edminsten, 590 F.

Supp. (E.D.N.C. 1984) at 367-378, nn. 28 and 32. These methods of

analysis — extreme case (or homogenous precinct) analysis and

bivariate ecological regression analysis — show differences in

candidate preferences among White and Black voters.21

These standard methods for determining the existence of bloc

voting "incorporate neither causation nor intent" for purposes of

section 2. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 62. In accordance with Congress'

intention to return to the pre-Mobile v. Bolden "results" or

21 "Extreme case analysis relies on a selected part of the

group to predict behavior of whole group. In an election context,

if you can find a precinct that is overwhelmingly one group, then

you can peform the extreme case analysis. For example, if you have

a precinct that is 100% Black and that precinct votes 80% for

candidate A, then you can extrapolate that 80% of all of the Blacks

voted for candidate A." Campos. 840 F.2d at 1246-1247 n. 10.

A regression analysis expresses the degree of

relationship between two variablees. The two variables are the

proportion of the of the voting age population that is Black (the

independent variable) and the electoral support _ for the Black

candidate (the dependent variable). "There is a positive

relationship between these two variables if the percentage of votes

supporting a black candidate tends to increase as _ the black

percentage of the voting age population in the precinct increases."

Gretna, 834 F.2d at 499 n. 7.

27

"effects" test, "the reasons black and white voters vote

differently have no relevance .to the central inquiry of §2."

Ginales. 478 U.S. at 62. Instead the court's focus should center

on the race and candidate selection differences. Id. Justice

Brennan, in addressing the appellants' argument in Gingles that

factors other than race, like party affiliation, may explain the

difference in candidate selection among white and Black voters,

cautions that such considerations under section 2 "would thwart the

goals Congress sought to achieve when it amended §2 and would

prevent courts from performing the "functional" analysis of the

political process..." Id.

Justice O'Connor disagrees with Justice Brennan's reasoning

on this point.22 She concludes that, "[e]vidence that a candidate

preferred by the minority group in a particular election was

rejected by white voters for reasons other than those which made

that candidate the preferred choice of the minority group would

seem clearly relevant" to the reviewing court's analysis.23 478

U.S. at 100. "Such evidence would suggest that another candidate,

equally preferred by the minority group, might be able to attract

greater white support in future elections." Id.

22 Justice O'Connor nevertheless concurs in the Court's

unanimous decision that the District Court in Gingles did not err

in determining that the other factors presented in Gingles to

explain voter behavior, such as campaign expenditures, name

identification and education, were insufficient to overcome the

clear evidence of vote dilution in violation of Section 2.

23 According to Justice O'Connor, when statistical evidence

of racially polarized voting is used for the limited purpose of

proving that the minority group is politically cohesive, and "to

assess its prospects for electoral success," defendants may not

then rebut this showing by pointing to causes other than race which

might explain a racial divergence in voting patters. 478 U.S. at

100.

28

Justice White, while not expressly disagreeing with Justice

Brennan's views on the irrelevance of causation, strongly disagrees

with Justice Brennan's view that the race of the voter and not the

candidate is relevant in statistical election analysis. 478 U.S.

at 33.

This conflict within the Supreme Court regarding the relevance

of causation and the race of the candidate in polarized voting, has

been resolved in this Court. In a trilogy of cases, this Court has

established well-developed standards for interpreting statisticasl

analyses of racially polarized voting.

2. Causation is Irrelevant to a Determination of

Polarized Voting

This Court has followed Justice Brennan's view that "the

reasons black and white voters vote differently have no relevance

to the central inquiry of § 2." In every case affirming the

presence of a discriminatory election scheme, this Circuit has

upheld the district court's findings based on the use of bivariate

regression analysis. See e.a.. Campos. 840 F.2d 1240 (5th Cir.

1988); Gretna. 834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987).

The kind of multivariate analysis advanced by the defendants

in this case, in which a different excuse can be invoked to explain

the loss of Black candidates in any number of elections, by its

very nature obfuscates the relevant question — whether the use of

a contested electoral practice results in Blacks having less

opportunity than other members of the electorate to elect

candidates of their choice. Ginqles, 478 U.S. at 55. See also,

Un. Latin Amer. Cit. v. Midland Ind. Sch. Dist, 812 F.2d 1494 (5th

29

Cir. 1987) ("Multivariate regression analysis is open-ended and

confusing"), vacated on other grounds. 829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir.

1987) .

This circuit, following the example set by the Supreme Court

in Ginales.24 evaluates the existence of White bloc voting based on

statistical evidence of racial voting patterns. Campos. 840 F.2d

at 1243. Reliance on the standard statistical methods employed in

vote dilution cases properly maintains the trial court’s focus on

the difference between the choices made by Black and White voters,

not the reason for the difference. Ginales, 478 U.S. at 63.

3. The Particular Salience of Elections Involving Both

Black and White Candidates

In Ginales. both the district court and the Supreme Court

relied on the results of the experts' statistical, analysis

concerning voter behavior in elections in which a Black voter faced

a white opponent. See. 478 U.S. at 52. Examination of such

elections, in which "blacks strongly supported black candidates

while. . . whites rarely did, satisfactorily addresses each facet

of the proper legal standard." Id. at 61. Five Justices found the

presence of a black candidate so important in determining bloc

voting that they suggested that only elections involving black and

white candidates can be probative.25 See id. at 83, 101.

24 As the court below noted, "the issue of partisan voting

was before the Supreme Court in Ginales. The Court had no

difficulty concluding that voting [was] polarized along racial, not

partisan, lines." Slip Op. at 80.

25 This court has noted that "[t]he various Ginales

concurring and dissenting opinions do not consider evidence of

elections in which only whites were candidates. Hence, neither do

30

Acknowledging that only a plurality of the Supreme Court found

the race of the candidate unimportant, this Circuit has affirmed

that "the evidence most probative or racially polarized voting must

be drawn from elections including both black and white candidates,"

since "evidence of black support for white candidates in an all-

white field...tells us nothing about the tendency of white bloc

voting to defeat black candidates." Westwego, 872 F.2d at 1208

n. 7, citing Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna, 834

F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987) . See also. Campos v. City of Baytown, 840

F.2d, 1240, 1245 ("district court was warranted in its focus on

those races that had a minority member as a candidate").

Finally, the importance of elections involving Black and white

candidates directly relates to the Senate Report's explicit

identification of "minority electoral success" within the

challenged jurisdiction as a probative factor in finding a

violation of section 2. S. Rep. No 97-417 at 29.

B. The District Court's Findings on White Bloc Voting

in Harris County

1. The District Court was not Persuaded by the

Appellants' Claims Regarding the Role of Party

Affiliation

The crux of the defendants' entire appeal is that party

affiliation, not race is the reason that Black candidates are not

elected in district judge races. This contention is wrong both as

a matter of fact and law. The District Court rejected the

defendant's contention on both grounds. The Court instead found

the results of the HLA plaintiff-intervenors' expert's analysis of

racially polarized voting in Harris County to be "legally competent

we." Gretna 834 F.2d at 504; see also Campos. 840 F.2d at 1245.

31

and highly probative." Slip Op. at 87.

a. In Fact, Party Affiliation Does Not Explain Why Blacks are

Not Elected as District Judges in Harris County

Dr. Engstrom, the expert for the HLA plaintiff-intervenors,

who performed both extreme case analysis and bivariate regression

analysis concluded, and the district court agreed, that "the Anglo

or white bloc vote in Harris county is sufficiently strong to

generally defeat the choice of the Black community." Slip Op. at

30. Dr. Engstrom further concluded that race, not party, is the

primary determinant of the outcome of district judge elections in

Harris County. TR. at 3-140.

The district court noted that Dr. Engstrom's conclusions were

based on his analysis of 17 contested district judge general

elections in which Black candidates faced white opponents. Sl’ip

Op. at 23-25. In 16 of these 17 elections, Black voters supported

the Black candidate. In each of these instances, the Black

candidate lost the election, never receiving more than 40% of the

white vote. See. Slip Op. at 96-97, Appendix A. The court

acknowledged Dr. Engstrom's testimony that the likelihood that the

strong correlation between race and voting patterns present in

Harris County occurred by chance, were less than 1 in 10,000. Slip

Op. at 24.

Defendant-intervenor Wood argues that the District Court

"excluded from consideration" evidence presented by the defendant

parties, that factors other than race, like political party,

explain the racial divergence in candidate preferences in judicial

elections in Harris County. Brief of Defendant-intervenor Wood at

32

34. This is simply not true. The court below considered

defendant-intervenors' arguments in this regard, but found them

unpersuasive and insufficient to rebut the strong evidence of

racially polarized voting presented by HLA plaintiff-intervenors'

expert, and conceded by the defendants' own expert. Slip Op. at

30-32; 79-80.

The District Court "rejects the State Defendants' argument

that there can be no 'functional view of the political process'

without taking into account political party as the principal factor

affecting" partisan judicial elections. Slip Op. at 89. Instead

the court takes the view that "it is unimportant whether a white

bloc vote, which is sufficient...usually to defeat the minority's

preferred candidate" is made up of Democrats or Republicans, once

the first two elements of Ginales have been proven and the Senate

factors point to vote dilution.26 Slip Op. at 79-80. The evidence

in the record supports the court's opinion.

On its own terms the defendants' argument fails to persuade.

HLA plaintiff-intervenors' expert, Dr. Engstrom, observed that

gross disparties exist in success rates among white and Black

candidates, even within the Democratic party. Dr. Engstrom

testified that 52% of white Democratic candidates won contested

district judge elections in Harris County from 1980 to 1988, while

only 12.5% of Black Democratic judicial candidates were simililarly

successful. TR. at 3-134-135. Dr. Engstrom further noted that

Black district judge candidates consistently fell in the bottom

Judge Mark Davidson testified that the Republican and

swing votes which decide the outcome of Harris County judicial

elections, are1cast by White voters. TR. at 3-331; 338.

33

half of vote getters among all Democratic judicial candidates

between 1980 and 1988. TR. at 3-135. This testimony was

corroborated by Judge Davidson. TR. at 3-342.

Finally, the defendant and defendant-intervenors'

interpretation of the nearly twenty year old decision in Whitcomb

v. Chavis. 403 U.S. 124 (1971) as analogous to the instant case is

mistaken. Whitcomb is clearly distinguishable from the case at

hand. As the court below explained,

In Whitcomb, the Supreme Court rejected a racial vote

diluation challenge to an at-large system for electing

state legislators, essentially on the ground that

partisan preference best accounted for electoral

outcomes in Marion County, Indiana. The Court in

Whitcomb concluded that there was no indication in

the record of that case that Blacks were being

denied access to the political system.

Slip Op. at 78-79. The Supreme Court's reversal in Whitcomb was

based, in large part, on evidence in the record that black and

white Democrats were equally unable to be elected in the challenged

jurisdictions. Because there was no disparity in candidate success

of Black and white voters within the Democratic party, the Court

asked:

"But are poor Negroes of the ghetto any more

underrepresented than poor ghetto whites who

also voted Democratic and lost, or any more

discriminated against than other interest

groups or voters in Marion County with

allegiance to the Democratic Party, or, conversely,

any less represented than Republican areas

or voters in years of Republican defeat?

403 U.S. at 154. This question is not applicable to Harris County

where a clear disparity exists between the success rates of Black

and white candidates, even within the same party.

34

In 1986, for example, when former Governor Mark White, at the

top of the ticket, led the majority of Democratic judicial

candidates to victory, all white incumbent Democratic judges were

reelected, while all the Black incumbent Democratic judges lost.27

Similarly, in 1982, when Democratic Sen Lloyd Bentsen and Gov.

Mark White were at the top of the ticket 12 of 13 White Democratic

candidates were elected while only one of the four Black Democratic

judicial candidates lost. See. Slip Op. at 98-100, Appendix A.

The only Black Democratic candidate to win in that election, was

Thomas Routt, an appointed incumbent. Judge Routt, garnering only

51.3% of the vote despite his incumbency, barely beat out his

opponent, a white virtual unknown. TR. at 3-162-163; TR. at 3-

329.

b. As a Matter of Law, the Defendants' Contentions

are Inaccurate

If the defendants' interpretation of the role of party

affiliation were adopted, discriminatory electoral systems using

partisan elections effectively would be immunized from section 2

attack. This result is entirely at odds with Congress' intent in

amending section 2.

The Voting Rights Act was designed to eliminate a "broad array

of dilution schemes," including those practices insulated within

the political party structure. S.Rep. at 6. The discriminatory

270ne of the incumbent Black judges who lost that year

testified that in her opinion, the Black incumbents were hurt by

the distribution of a Democratic Party campaign mailing, which

included a group photograph of all of the incumbent Democratic

judicial candidates. This campaign literature was mailed to voters

througout the county. See. Deposition Summary of Bonnie Fitch, TR.

at 3-209.

35

effect of such practices on the ability of Blacks to participate

in the political process, such as the Texas Democratic party's use

of an all white primary, is undisputed. See Smith v. Allwriaht,

321 U.S. 649 (1944).

2. Appellants' Claims Regarding the Role of

Bar Polls, Endorsements and Similar Factors

Is Irrelevant as a Matter of Law

As an alternative to their argument that party affiliation

and not race, explains the divergence in the success of Black and

white candidates in Harris County, defendant-intervenor Wood

introduced a barrage of hypothetical, unscientifically applied

explanations for why Black candidates lost elections. These

explanations included, but were not limited to: failure to win the

Houston Bar Poll, lack of campaign funds, negative campaign

publicity, and failure to obtain endorsements. The District Court

found this argument "legally incompetent." Slip Op. at 31.

The district court's decision in this regard as well, is

supported by the record. Defendant-intervenor Wood failed to

demonstrate any consistent pattern in applying these factors to

various elections.28 The Supreme Court has found that the type of

inconsistent, unscientifically applied explanation for racial

disparities offered by defendant-intervenor Wood are entitled to

little or no probative weight. Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385,

404 (1986). Defendant-intervenor Wood "declare[s] simply that many

factors" affect the outcome of judicial elections; "they made no

Defendant-intervenor Wood also failed to present any