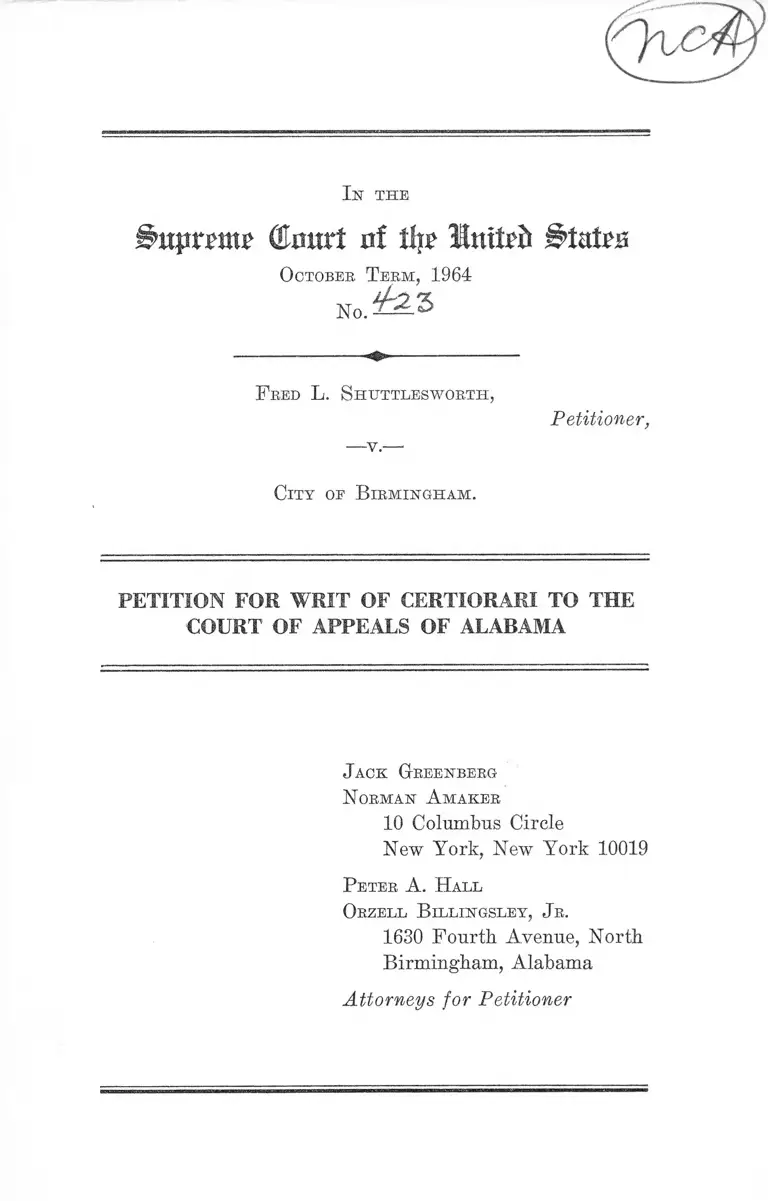

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1964

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1964. 29bb8654-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/94068b58-e011-49a1-80c3-a0bf5fe6991b/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(Emtrt ai % Intuit States

O ctober T erm , 1964

No. £ 2.3

F red L. S htjttlesworth ,

— v.-

Petitioner,

Cit y of B ir m in g h a m .

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

N orman A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley , J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ........... ................ ........ ..... 1

Jurisdiction ..„......................................................... ........ . 2

Questions Presented .............................................. ....... . 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ....... 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

B elow .................................. - ............................................ 10

Reasons for Oran ting the Writ ......................... 11

I. Petitioner’s Conviction Was Affirmed on a

Record Containing Ho Evidence of His Guilt

Contrary to the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment .................................... 11

II. Petitioner’s Conviction Was Secured Under

Ordinances Which as Applied to His Conduct

Are Unconstitutionally Vague .................... 16

Conclusion ............................................. 19

A ppendix ...... la

Order and Judgment of the Alabama Court of

Appeals ...................................................... 6a

Order of Alabama Court of Appeals Denying

Rehearing _____ 7a

Orders of the Supreme Court of Alabama ........... 8a, 9a

11

T able of Cases

page

Bouie v. City of Columbia,------U. S .------- , 12 L. ed. 2d

894 (1964) ......................... ........ ...... .............................. 17

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 (1948) ________ _____ 13

Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. E.

2d 666 (1950) ..... .............. .......... ....... ........ .............. . 17

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385

(1926) ............................................................................... 17

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 (1947) .................. 13

Drummond v. State, 37 Ala. App. 308, 67 So. 2d 280 ..12, 3a

Ex Parte Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35 (1962) .............. 16

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 (1963) ....... 13

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) ................... 13

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 459 (1939) ............... 17

Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 160 So. 2d 898, cert. den.

160 So. 2d 902 .......... ........ .......... .......... .......... .......... 5,18

Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 6 Div. 930, Ct. of

Appeals Manuscript ...................................................... 3a

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, cert. den. 368

U. S. 959 (1962) ......................... .................... ............. 16

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262

(1963) ............................. ................................................ . 16

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339

(1964) ^ .... .............. 13,16

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 TJ. S. 154...... ................ .......... . 13

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ........ .......... 12,13,17

Wright v. Georgia, 373 IT. S. 284 (1963) ...................12,17

Ill

S tatutes

page

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) ________ __________ _________ ___ 2

General City Code of Birmingham, §1142 (as amended

by §1136- F) ............................... ............ ........... ....3, 4,10, la

General City Code of Birmingham, §1231 .......... ........ 3, 4,10

Other A uthorities

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative

Draft, No. 13, p. 1 4__ ____ _____ ____ _______________ 17

Douglas, “Vagrancy and Arrest on Suspicion,” 70 Yale

L. J. 1 (1960) ............................. .... ....... ....................... 17

In the

(tart uf % Intirft Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1964

N o.------

F red L . S h u ttlesw orth ,

— v . —

Petitioner,

City oe B ir m in g h am , A labam a .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAMA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Alabama Court of Appeals entered in

the above-entitled case on November 19, 1963, rehearing of

which was denied on January 7, 1964. A petition for writ

of certiorari was denied by the Supreme Court of Alabama

on February 20, 1964 and rehearing was denied on March

26, 1964.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Alabama Court of Appeals (R. 143) is

reported at 161 So. 2d 796 and is set forth in the appendix

hereto, infra, p. la. The Supreme Court of Alabama ren

dered no opinion but its order denying certiorari is re

ported at 161 So. 2d 799.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Alabama Court of Appeals (R. 142)

was entered on November 19, 1963, appendix, infra, p. 6a.

Application for rehearing was overruled January 7, 1964

(R. 147), appendix, infra, p. 7a.

A petition for certiorari filed in the Supreme Court of

Alabama was denied on February 20, 1964 (R. 154), appen

dix, infra, p. 8a and an application for rehearing was

denied on March 26, 1963 (154), appendix, infra, p. 9a.

On June 17, 1964, Mr. Justice Black extended petitioner’s

time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari in this Court

to August 23, 1964.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below, and

asserting here, deprivation of rights, privileges and immu

nities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner was denied due process of law

contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States by his conviction on a record contain

ing no evidence of his guilt.

2. Whether petitioner was also denied due process of

law by his conviction under ordinances which as applied

to his conduct are unconstitutionally vague, under the

Fourteeenth Amendment.

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Section 1142 of the General

City Code of Birmingham as amended by Ordinance No.

1436-F:

S treets and S idew alks to B e K ept O pen for F ree

P assage.—Any person who shall obstruct any street or

sidewalk or part thereof in any manner not permitted

by this code or other ordinance of the City with any

animal or vehicle, or with boxes or barrels, glass, rub

bish or display of wares, merchandise or sidewalk

signs or other like things, so as to obstruct the free

passage of persons on such streets or sidewalks or

any part thereof, or who shall assemble a crowd or hold

a public meeting in any street without a permit, shall,

on conviction, be punished as provided in Section 4.

It shall be unlawful for any person or any number

of persons to so stand, loiter or walk upon any street

or sidewalk in the City as to obstruct free passage

over, on or along said street or sidewalk. It shall also

be unlawful for any person to stand or loiter upon any

street or sidewalk of the City after having been re

quested by any police officer to move on.

and Section 1231 of the General City Code of Birmingham:

Obedience to P olice.—It shall be unlawful for any

person to refuse or fail to comply with any lawful

order, signal or direction of a police officer.

4

Statement

Petitioner, Fred L. Shuttlesworth, a “ notorious person

in the field of civil rights in the City of Birmingham” (R.

48) was arrested on the morning of April 4, 1962 outside

Newberry’s Department Store at 19th Street and 2nd Ave

nue North in Birmingham, Alabama. He was tried and

convicted in the City Recorder’s Court of violating Sections

1142 (as amended by Section 1436-F) and 1231 of the Gen

eral City Code of Birmingham and sentenced to a fine of

$100.00 and costs and 180 days at hard labor (R. 1).

On appeal to the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, he

was charged in a complaint containing two counts. Count

one charged that F. L. Shuttlesworth:

“ . . . did stand, loiter or walk upon a street or side

walk within and among a group of other persons so as

to obstruct free passage over, on or along said street

or sidewalk at, to-wit: 2nd Avenue, North, at 19th

Street or did while in said group stand or loiter upon

said street or sidewalk after having been requested by

a police officer to move on, contrary to and in violation

of Section 1142 of the General City Code of Birming

ham of 1944, as amended by Ordinance Number 1436-F”

(R. 2).

Count two complained that petitioner:

“ .. . did refuse to comply with a lawful order, signal

or direction of a police officer, contrary to and in vio

lation of Section 1231 of the General City Code of

the City of Birmingham” (R. 2).

In the Circuit Court, he was tried without a jury on October

29-30, 1962 (R. 15, 93), convicted and sentenced to $100

and costs, 52 days for failure to pay the fine and costs and

180 days at hard labor (R. 11).

The Alabama Court of Appeals on November 19, 1963,

affirmed petitioner’s conviction (R. 142), infra, p. 6a.

James Phifer, arrested simultaneously with Shuttles-

worth, was tried with him on identical charges in the Cir

cuit Court (R. 15-16) but his conviction was reversed by

the Alabama Court of Appeals because of insufficiency of

evidence, Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 160 So. 2d 898,

cert. den. 160 So. 2d 902.

At the trial in Circuit Court the evidence offered by the

City and that offered on behalf of petitioner and his co

defendant were in substantial contradiction. The City’s

chief witness, Police Officer Robert Byars who arrested

petitioner, testified that about 10:30 a.m. on the morning of

the arrest, he was standing on 19th Street just north of the

alley between 2nd and 3rd Avenue North adjacent to New

berry’s Department Store (R. 17). He saw petitioner and

Phifer walking south on the west side of 19th Street toward

2nd Avenue “ in company with three or four other people”

(R. 17). Officer Byars then entered the alley entrance to

Newberry’s store located on the west side of 19th Street

just north of the store (R. 17), walked through the store

to the front entrance at the northwest corner of 2nd Ave

nue and 19th Street North (R. 18). From inside the en

trance doorway, he looked out on the street (R. 18, 27) and

saw petitioner “ standing with a group of some ten or twelve

people all congregated in one area” (R. 18). He observed

the group “ for a minute to a minute and a half while they

stood” (R. 19). The group was “ standing and listening and

talking” (R. 18). “ On some occasions,” according to his

testimony, “ people who were walking in an easterly direc

tion on the north side of 2nd Avenue had to go into the

street to get around the people who were standing there”

(R. 18).

0

6

He testified that he then “walked out of the store and in

formed the group of people they would have to move on and

clear the sidewalk so as to allow free passage and not to

obstruct it” (R. 19). “ [S]ome of the group began to move

gradually away” (19). “ Not all of them began to move”

and he “waited for a short time and again informed them

they would have to move . . . ” (19). At this point, peti

tioner Shuttlesworth is reported to have said “you mean to

say we can’t stand here on the sidewalk” or words to that

effect (19). Officer Byars “ said nothing in return,” “ hesi

tated again for a short time and informed them for the

third and last time . . . they would have to move” (19).

Petitioner then supposedly said “do you mean to tell me

we can’t stand here in front of this store?” at which time

the officer informed him that he was under arrest (19).

According to Byars’ testimony, Shuttlesworth then said,

“ Well, I will go into, the store” and started into the en

trance of Newberry’s Store (19). The officer stated: “he

got inside the door and I reached and got him and told him

again he was under arrest” (19).

Petitioner was then placed into custody “ and taken to

the west curb to await transportation to the City Jail”

(R. 20).

Pedestrian traffic “was normal for a Wednesday at that

particular time of day” (R. 21). When Byars first saw the

group, they were walking south and not violating any ordi

nance or obstructing any traffic (R. 27). After he came out

of the store and spoke to the group, he testified that “ every

body else was in motion except the Defendant, Shuttles

worth, who had never moved” (R. 30). “No other person

made any statement to [him] other than the defendant,

Shuttlesworth . . . ” (R. 20-21).

Other police officers corroborated Byars’ testimony. Offi

cer Renshaw testified that he first saw Byars when he was

7

talking to the group (R. 49); that he got off his motorcycle

and walked over to the crowd (R. 49-50); that he heard

Byars say, “ For the third and last time, I am telling you

you got to . . . move on, or words to that effect” (R. 51);

that there were “ eight or ten or twelve” persons in the

crowd, “ all colored” (R. 51) and that he recognized Shut-

tlesworth and assisted in his arrest (R. 50).

Officer Hallman testified that Byars called him and Officer

Davis over from the southeast corner of 2nd Avenue and

19th Street North and that he went over and just as he

stepped on the curb he heard Byars say, “ I am telling you

for the third time you will have to move on, you are block

ing the crosswalk” (R. 62). He testified that there were 5 or

6 persons in the group and they all dispersed upon direc

tion except Shuttlesworth (Id.).

f

Officer Byars testified that Shuttlesworth offered “no re

sistance” (R. 31) to the arrest. Another officer testified

that force was not necessary in making the arrest (R. 50);

that petitioner was “ a docile prisoner” (R. 58) and that he

did not give the arresting officers “ any difficulty at all”

(R. 58).

The evidence for the defense presented a very different

version of what occurred. The petitioner testified that his

co-defendant Phifer and a man named James Armstrong

had been in federal court that morning and after leaving

there walked down 19th Street “walking as pedestrians

walk approaching the light at the intersection of 19th Street

and 2nd Avenue North . . . ” (R. 115). As they approached

the intersection, “ [ajlmost instantaneously or simultane

ously with me as I got practically to the corner the officer

came out of this door to my right and stepped in front of

me” (Id.). The officer then said “move on” whereupon peti

tioner inquired “move where officer” (Id.). Byars said

“ anywhere but here, but move on” at which point peti

tioner said “all right, I will go into the store” (Id.). At this

point, petitioner turned and walked into the corner en

trance to Newberry’s store and had gotten approximately

“ four or five steps inside the store” when the officer said

“you are under arrest” (Id.).

Petitioner Shuttlesworth further testified that it was the

police officer who stopped him; he “would have had maybe

another step or two to the curb” (E. 125). He stated that

he never got to the corner and that “ [h]ad I walked on I

would have walked into him” (E. 116). The first time that

he was informed that he was under arrest was when the

officer stopped him in the store; the officer had not men

tioned arrest before then (E. 121). Petitioner then con

tinued :

Q. When were you told why you were arrested? A.

When was I told why ?

Q. Yes, on what charge you had been arrested on?

A. I believe the only time that I heard of it—some

officer came to the car as Phifer and I were sitting

inside discussing what they were going to put against

us or something like that.

Q. They were discussing the charge to put against

you? A. Yes (E. 119-120).

Petitioner’s co-defendant, Eev. Phifer, testified that he

and Eev. Shuttlesworth didn’t stand on the corner at all

(E. 131) ; that contrary to Officer Byars’ testimony, Byars

did not speak three times to petitioner or to the crowd

(Id.); that in fact “ [w]e were approaching the corner.

We hadn’t stopped” (E. 132); that Byars stepped around

in front of Shuttlesworth “before we got to the curb” (Id.)

and that he addressed his words only to Shuttlesworth (Id.).

Armstrong testified that he was with Shuttlesworth and

Phifer on the morning of April 4th and that Byars came

9

out of Newberry’s store when “ [w]e were still moving com

ing to the corner” (R. 86), “ placed himself in front of . . .

Reverend Shuttlesworth” so he couldn’t move (R. 86) and

pointed to Shuttlesworth and told him to “ move on” (R. 85).

On cross-examination, he stated there were only four or

five people in the group coming from the courthouse and

“ some of them were behind and when they got to the inter

section they did not meet any friends there nor any one

that knew Rev. Phifer or Rev. Shuttlesworth” (R. 90).

When asked: “How long were you standing at that inter

section,” he answered: “ I was walking to the intersection.

I didn’t get a chance to stand” (R. 91).

Another defense witness, Rev. Norris, testified that he

was walking about 5 feet behind Shuttlesworth (R. 94);

that when he first saw Officer Byars he was “ passing the

door just before you get to the corner” on the inside of

Newberry’s store as he, Norris, was passing on the outside

(R. 94); that Byars came out from the entrance to New

berry’s store walked around in front of Shuttlesworth and

said “move on” whereupon Shuttlesworth said “ move where

officer” and Byars replied “ anywhere but here” (R. 94).

Norris testified that the only crowd that collected consisted

of white and Negro persons standing there watching the

officer and Shuttlesworth (R. 99), that there was “ quite a

number out there on that corner observing this arrest”

(R. 100).

Another witness, Simpson Hall, testified that: “Before

the Reverend Phifer and Shuttlesworth could get to the

light he come and kind of stepped in front of Reverend

Shuttlesworth and told him to move on” (R. 110). He and

another witness, Walter King, testified that they only heard

the officer ask Shuttlesworth to move one time (R. 110-106).

The entire arrest incident from the time the officer walked

up to the intersection until the time he told Shuttlesworth

that he was under arrest took less than a minute (R. 133).

10

The Court of Appeals did not attempt to reconcile the

conflicts in testimony, holding that “ the grounds set out and

argued in appellant’s (petitioner’s) motion for new trial

. . . were properly overruled as sufficient evidence was

introduced for the court to find the defendant guilty under

the complaint” (R. 145).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Relow

Petitioner filed a motion to quash the complaint (R. 3)

alleging that “ the allegations of the complaint, and each

count thereof, are so vague and indefinite, as not to apprise

this defendant of what he is called upon to defend” ; that

“ Sections 1231 and 1142 of the 1944 General City Code of

Birmingham, under which said complaint is brought, as

applied to this defendant, violates . . . the First and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States

of America; “ that the aforesaid Sections 1231 and 1142

as applied to the defendant is unconstitutional on its face,

and that it is so vague as to constitute a deprivation of

liberty, without due process of law, in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment of the United States” (R. 3-4).

Petitioner also filed a demurrer alleging abridgment of

his rights of free speech and assembly under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments; a violation of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because of unconsti

tutional vagueness of the ordinances and a violation of the

privileges and immunities and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 5-6).

At the close of the City’s case (R. 81) and again at the

close of all the evidence (R. 137), petitioner filed a motion

to exclude the evidence on the ground that there was no

evidence to support the complaint and that all the evidence

11

showed was that petitioner was exercising rights and priv

ileges guaranteed him by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments (R. 7).

At the end of trial (R. 138), petitioner filed a motion for

new trial renewing the allegations contained in the previous

motions (R. 8-9).

All of petitioner’s motions were overruled and petitioner

was found guilty as charged (R. 10-11).

Petitioner renewed his federal constitutional claims by

assignments of error to the Alabama Court of Appeals

(R. 141) which without consideration of his constitutional

claims affirmed his conviction (R. 142) infra, pp. la-5a. The

Alabama Supreme Court denied petitioner’s timely filed

application for writ of certiorari (R. 154) and overruled

his application for rehearing (Id.) infra, pp. 8a-9a.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below conflicts with applicable decisions of

this Court on important constitutional issues.

I

Petitioner’ s conviction was affirmed on a record con

taining no evidence o f his guilt contrary to the due

process clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment.

In affirming petitioner’s conviction, the Alabama Court

of Appeals did not consider the evidence contradicting the

City’s version of the circumstances leading to petitioner’s

arrest but merely upheld the Circuit Court’s overruling of

petitioner’s motion to exclude the evidence, stating that

“ [w]hen there is sufficient evidence on the part of the

prosecution to make out a prima facie case, a motion to

12

exclude the evidence should be overruled. Drummond v.

State, 37 Ala. App. 308, 67 So. 2d 280” (R. 145).

But fully accepting the City’s version of the facts, there

is no evidence that petitioner committed a crime. He was

charged under the language of the second paragraph of

section 1142 for obstructing free passage or for standing

or loitering after being reqeusted to move on (R. 2). But

neither petitioner nor anyone else was arrested for obstruc

tion of passage along the sidewalk for, as officer Byars

testified, everyone obeyed his order to move (R. 37) “ except

the Defendant Sliuttlesworth, who had never moved” (R.

30). Thus, Shuttlesworth’s arrest appears to have been

made only for failing to move when ordered to do so. But

the evidence shows that petitioner did move—he started

into the store; in the words of another officer, he “ [j]ust

walked off with the rest of the crowd” (R. 54). And if, as

the City says, petitioner had already been placed under

arrest when he began to move, it is clear that the only

possible reason for his arrest was that he was the only

person who made any statements to the officer while he

was allegedly issuing his command to the crowd to move.

According to the City’s testimony, those statements were

“ do you mean to tell me we can’t stand here in front of

this store” (R. 19) and “well, I will go into the store” (19).

Even if these peaceful statements (and there is no evidence

that petitioner was anything other than peaceful) could

be construed as arguing with the policeman, petitioner still

did nothing criminal. Cf. Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S.

199, 206; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 286.

Petitioner’s conduct, which consisted of making state

ments to a police officer and attempting to go into New

berry’s store, is certainly not evidence of standing or loiter

ing after being requested to move or of failing to comply

with the lawful order of a policeman. To convict petitioner

13

on. no evidence of substantial elements of the crime with

which he was charged is a violation of due process. Thomp

son v. Louisville, , supra; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157 (1961) ; Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154; Fields v.

City of Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 (1963). And if it could some

how be assumed that these acts were criminal, they were

not charged. It is equally a violation of due process to

convict a man of a crime not charged. DeJonge v. Oregon,

299 U. 8. 353, 362 (1937); Cole v. Arkansas, 333 TJ. S. 196,

201 (1948); Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S.

339 (1964).

But the evidence presented on behalf of the defense easts

strong doubt on the version of the arrest given by the

City. Moreover, none of the contradictory testimony

offered by the defense was challenged by the city’s attor

ney on cross-examination (R. 90-91; 100-101; 109; 113;

121-124; 127-128; 36). The only things agreed upon by the

respective witnesses for the city and the defense were the

time and place of the incident and the fact of petitioner’s

arrest.

Thus, the number of persons involved was disputed,

being estimated by the city’s witnesses as 10 to 12 (R. 18,

40, 51, 76), by the defense witnesses as no more than 4

or 5 (R. 84, 86, 90).1 Also disputed is why the crowd col

lected, the city’s version being that petitioner stopped and

congregated with a group of 10 to 12 persons who were

“ just standing and listening and talking” (R. 18) while

the defense testified that no persons or friends met peti

tioner and his companions at the eorner (R. 90) and fur

ther that.no crowd collected until the police officer entered

1 In fact, Officer Byars testified that when he first saw petitioner

he was in the company of only 4 or 5 other persons and he did not

know “where the. additional people . . . came from” (R. 40). But

his.fellow officer, Hallman, testified, that there were only 5 or 6

people in the group talking to Byars (R. 62).

14

the picture (R. 99). Whether the crowd was all Negro

(R. 51) or composed of whites and Negroes (R. 99, 106)

was also at issue as was the length of time during which

the incident occurred, Officer Byars having testified that

he stood inside the entrance door to Newberry’s watching

petitioner and his companions assembled on the corner

“ for a minute to a minute and a half” (R. 18) and spent

another “ minute or minute and a half talking to them out

side trying to encourage them to move” (R. 34) while peti

tioner and the other defense witnesses testified that they

were accosted by Officer Byars while in motion approach

ing the corner and did not stop and stand on the corner

(R. 91, 110, 116, 131-132) and thus the entire arrest inci

dent took less than a minute (R. 118, 133). Also directly

challenged by the defense evidence was the testimony of

the primary arresting officer that he spoke to the allegedly

assembled crowd three times requesting them to move on

(R. 19); the witnesses for the defense testified uniformly

that Officer Byars emerged from Newberry’s store and

placed himself directly in front of petitioner and said to

him once only and to no one else “ Move on” (R. 94, 104,

106, 110, 115). Whether petitioner was placed under arrest

before entering the store was also disputed as Byars testi

fied that Shuttlesworth was arrested before he moved (R.

21) while petitioner (R. 121) and others (R. 97, 109) testi

fied that he was not placed under arrest until he started

into the store.

In addition, Byars testified on direct examination that

petitioner’s group was standing in the western half of the

western crosswalk of 2nd Avenue and 19th Street North

(R. 18) and that as he was observing them from the inside

of Newberry’s store “ on some occasions people who were

walking in an easterly direction on the north side of 2nd

Avenue had to go into the street to get around the people

who were standing there” (R. 18). But on cross-examina-

15

tion the defense counsel diagrammed the scene on a black

board (R. 21) and Officer Byars drew an X to mark the

spot where petitioner’s group was allegedly congregated

(R. 22). He then testified as follows:

Q. I saw (sic) assuming the defendants were stand

ing where you drew that little mark there, that would

have left more than half of this north-south crosswalk

free, would it not? A. That is true.

Q. And they didn’t block the east-west crosswalk at

all did they? A. They did not (R. 22-23).

These discrepancies were glossed over completely by the

Alabama Court of Appeals but the record taken as a whole

makes it clear that the version of the facts given by the

witnesses for the defense is the correct version. In any

event, petitioner need not rely on his own evidence, though

it demonstrates how specious were the charges against

him. Even under the state’s version he was guilty of no

crime. See pp. 12 to 13, supra.

The record moreover supports an inference that the

real reason for petitioner’s arrest and conviction was his

civil rights activities in the City of Birmingham. At the

time of his arrest there was a selective buying campaign

going on in Birmingham on the part of the Negro com

munity (R. 25, 66, 81, 125, 136). Defense counsel attempted

to show that petitioner’s arrest was part of a police tactic

of harassment in retaliation for Ms course of civil rights

conduct which had resulted in numerous other arrests by

the Birmingham Police Department (R. 25, 48, 80, 118,

119). The Circuit Court sustained the City’s objections to

this line of questioning (R. 119) and the Court of Appeals

affirmed (R. 146). However, the only plausible explana

tion of this conviction on no evidence is that it was part

of a campaign of harassment against him for his civil

16

rights activities (R, 48). This should be considered with

petitioner’s many arrests by the Birmingham police over

a number of years (R. 48)2 and the number of occasions

that these arrests and subsequent convictions have been

brought to this court.3 Only in this context does such a

baseless prosecution make sense.

II

Petitioner’s conviction was secured under ordinances

which as applied to his conduct are unconstitutionally

vague.

As demonstrated in I, supra, what caused petitioner’s

arrest on this occasion (aside from his civil rights activi

ties) was that he “ talked back” to the officer by asking him

(taking the City’s evidence as a true version of the events

that transpired) “ do you mean to tell me that we can’t

stand here in front of this store” (R. 19) and then at

tempted to enter Newberry’s store when ordered to move

2 1958: ( 1) Reckless driving; 2) Consipiring to commit a breach

of the peace; 3) Inciting a violation of disorderly con

duct ordinance)

1960: ( 1) Speeding; 2) Aiding and abetting law violation;

3) Giving false information to officer)

1961: ( 1)Violation of peace bond ordinance; 2) Refusing to

obey lawful command of officer and interfering with

officer in discharge of duty)

1962: (Loitering after warning and failing to obey officer (this

case))

1963: ( 1) Parading without a permit; 2) Parading without a

permit) :

3 Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, cert. den. 368 U. S. 959

(1962) (Conviction for disorderly conduct); Ex Parte Shuttles

worth, 369 U. S. 35 (1962) (Application for writ of habeas corpus

after affirmance of conviction of disorderly conduct) ; Shuttlesworth

v. City of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262 (1963) (Conviction for aiding

and abetting violation of trespass ordinance) ; Shuttlesworth v.

City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339 (1964) (Conviction of inter

fering with officer in discharge of his duty affirmed by Ala. Court

of Appeals on basis of City’s assault ordinance).

17

on. But petitioner was charged under two ordinances, one

of which makes it a crime to stand or loiter upon a street

after being told to move (Section 1142) the other of which

makes it a crime not to comply with a lawful order of a

police officer (Section 1231).4

Petitioner could not know that (1) asking a question

and (2) going into the store amounted to standing or

loitering after an order to move, the conduct interdicted

by Section 1142 or failing to obey the lawful command of

an officer, the conduct proscribed by Section 1231. Peti

tioner, therefore, was not given adequate prior warning

by the language of either of these ordinances that his

peaceful inquiry or his entering the store was a violation

of their terms. Thus his conviction under these or

dinances is contrary to prior decisions of this court, Con

nolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385, 391

(1926); Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 IT. S. 459 (1939);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963); Bouie v. City of

Columbia,------ U. S . -------, 12 L. Ed. 2d 894 (1964). See

also Thompson v. Louisiana, 362 U. S. 199, 206 citing Lan-

setta, supra. Indeed, the Thompson case contains ele

ments of both the “ no evidence” and “ lack of fair warn

ing” aspects of procedural due process in that the defen

dant there made peaceful inquiry of the arresting officer

as to what was wrong with his conduct and was charged

and convicted under an ordinance that did not apprise him

4 The validity of such ordinances restricting as they do the right

to make peaceful and ordinary use of the public streets is open to

question. See Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. E.

2d 666 (1950). This is particularly true where the ordinances con

tain no guides to limit police action which “often reflect(s) affront

to the policeman’s personal sensibilities rather than vindication of

the public interest.” American Law Institute, Model Penal Code,

Tentative Draft No. 13, p. 14. See also Douglas, “Vagrancy and

Arrest on Suspicion,” 70 Yale L. J. 1 (1960).

18

of the fact that what he was shown to have been doing

came within the ambit of its proscription.

With particular regard to Section 1231 of the City

Code, its inapplicability to defendant’s conduct is demon

strated by the Alabama Court of Appeals’ opinion in the

companion case of Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 160 So.

2d 898. In reversing Eev. Phifer’s conviction, the Court

stated:

“The charge in the second count of the complaint

is for a violation of Section 1231, of the General

City Code of Birmingham. This section appears in

the chapter regulating vehicular traffic and provides

for the enforcement of the orders of the officers of

the police department in directing such traffic. There

is no suggestion in the evidence that the defendant

violated any traffic regulation of the city by his

refusal to move away from Shuttlesworth when

ordered to do so.” 160 So. 2d at 901.

Likewise, there is no evidence that petitioner violated

any traffic regulation of the City by making peaceful in

quiry of the officer and attempting to enter Newberry’s

store. Thus, the application of Section 1231 to petitioner’s

conduct to sustain his conviction requires that that con

viction be voided for unconstitutional vagueness. Cer

tiorari should be granted because petitioner was convicted

under ordinances which, as shown by the proof, had noth

ing to do with his conduct which was at all times peaceful

and lawful.

19

CONCLUSION

This case is another instance of petitioner’s unfair

treatment by state authority because of his civil rights

activities in Birmingham. That he could be arrested,

brought to trial and convicted on the basis of what is

shown on this record is incredible and denies fundamental

precepts of due process required by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Such a conviction should not be permitted to stand.

It is therefore, respectfully submitted that the petition

for writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

N orman A m aker

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A . H all

Orzell B illingsley , J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I X

la

APPENDIX

Opinion o f the Alabama Court o f Appeals

T he S tate oe A labama— J udicial D epartm ent

T he A labam a Court oe A ppeals

O ctober T erm , 1963-64

6 Div. 929

F. L. S h u ttlesw orth ,

—v.—

C ity oe B ir m in g h a m .

Appeal from Jefferson Circuit Court

P er Cu r ia m :

Appellant, Fred L. Shuttlesworth, appeals from a convic

tion by the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, Alabama,

of violating Sections 1142 and 1231 of the General City

Code of Birmingham, Alabama. The case was heard by

the Circuit Judge sitting without a jury. The first count

of the complaint charges the appellant with loitering on a

street corner with others so as to obstruct free passage

along the sidewalk. The other count charges appellant with

failure to obey the lawful command of a police officer.

Section 1142 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

Street and Sidewalks to Be Kept Open For Free Passage,

reads:

“Any person who shall obstruct any street or side

walk or part thereof in any manner not permitted by

this code or other ordinance of the city with any animal

2a

or vehicle, or with boxes or barrels, glass, trash, rub

bish or display of wares, merchandise or sidewalk

signs, or other like things, so as to obstruct the free

passage of persons on such street or sidewalks or any

part thereof, or who shall assemble a crowd or hold a

public meeting in any street without a permit, shall, on

conviction, be punished as provided in Section 4.

“ It shall be unlawful for any person or any number

of persons to so stand, loiter or walk upon any street

or sidewalk in the city as to obstruct free passage over,

on or along said street or sidewalk. It shall also be

unlawful for any person to stand or loiter upon any

street or sidewalk of the city after having been re

quested by any police officer to move on.”

Section 1231 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

Obedience to Police, reads as follows:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person to refuse or

fail to comply with any lawful order, signal or direc

tion of a police officer.”

The evidence, as introduced by the City, tended to show

that the defendant was a member of a crowd of about ten

or twelve people standing on the corner of 19th Street and

2nd Avenue, North, in the City of Birmingham, and that

this crowd was blocking the sidewalk to such an extent that

some of the other pedestrians were forced to walk into the

street to get around them. The crowd was accosted by one

Officer Byars and asked to clear the sidewalk so as not to

obstruct pedestrian traffic. The evidence further showed

that the crowd remained and when requested to disperse

for the third time by Officer Byars, defendant Shuttlesworth

said, “ You mean to tell me we can’t stand here in front of

this store?” at which time Officer Byars informed the defen

dant that he was under arrest. Officer Byars testified that

3a

at the time of the arrest everyone had moved or was moving

away except Shuttlesworth. After being told that he was

under arrest, Shuttlesworth moved away saying, “Well I

will go into the store.” Officer Byars then followed Shut

tlesworth into Newberry’s Department Store and took him

into custody.

The appellant’s first two assignments of error addressed

to the action of the lower court in overruling appellant’s

motion to Quash and Demurrers to the complaint were

overruled on the authority of Phifer v. City of Birmingham,

6 Div. 930, Ct. of Appeals Manuscript, which case was com

bined and tried with this one.

The third assignment of error presented by appellant is

that the Court erred in denying and overruling the defen

dant’s motion to exclude the testimony and for judgment.

When there is sufficient evidence on the part of the prose

cution to make out a prima facie case, a motion to exclude

the evidence should be overruled. Drummond v. State, 37

Ala. App. 308, 67 So. 2d 280.

Appellant’s fourth assignment of error was that the court

erred in denying and overruling defendant’s motion for a

new trial. All the grounds set out and argued in appellant’s

motion for new trial, except ground 11, were grounds of

a general nature and were properly overruled as sufficient

evidence was introduced for the court to find the defendant

guilty under the complaint.

The 11th ground of appellant’s motion for a new trial is

the same as his fifth assignment of error and reads:

“ The court erred in sustaining the objections by the

City of Birmingham as to reasons for the arrest and

conviction of the appellant, especially regarding his

civil rights activities.”

The following objections and rulings of the court thereon

are alleged to be error by the appellant:

“ Q. There was a trial then pending in the Federal

Court, is that correct? A. That’s right, on my release

from jail.

“ Q. Release from jail? What were the circumstances

of your being in there?

“Mr. Walker: We object, Tour Honor. That has

no bearing on this case.

“ Mr. Hall: If Your Honor, please, we insist it is

very pertinent. It goes to our theory the reason for

the arrest and the heavy penalty.

“Mr. Walker: Tour Honor, this is getting far

afield from the charge.

“ The Court: Sustain the objection.

“ Mr. Hall: We want an exception, Tour Honor.

“ Q. Was there wide publicity given to this Federal

hearing? A. Tes.

“ Q. Had it been published in the newspapers? A.

It had.

“ Q. Was there publicity over the radio and by way

of the television?

“Mr. Walker: We object to this.

“The Court: Sustained.

“Mr. Walker: It serves no purpose.

“Mr. Hall: Exception, Your Honor.

“ Q. How many times have you been arrested by the

police of the City of Birmingham because of your civil

rights activities?

“ Mr. Walker: We object, your Honor. Immaterial.

“ The Court: Sustained.

“ Mr. Hall: We except, Tour Honor.”

“ Q. Why was it necessary for yon to leave 19th

Street and 2nd Avenue and go to 16th Street and 5th

Avenue to get a cup of coffee?

“ Mr. Walker: We object to that, Your Honor, why.

“ Mr. Hall: Mr. Walker brought it out on cross-

examination. He made a big show of the distance.

“ The Court: Leave it out.

“ Mr. Hall: We want an exception, Your Honor.”

The sustaining of the objections to the foregoing ques

tions was proper as such questions were irrelevant and

immaterial to the issues involved.

The trial court, therefore, did not err by sustaining such

objections.

The judgment of the Circuit Court is

Affirmed.

5a

6a

Order and Judgment o f the Alabama Court o f Appeals

T he S tate of A labama— J udicial D epartm ent

T h e A labama C ourt of A ppeals

O ctober T erm , 1964

6 Div. 929

F. L. S h u ttlesw orth ,

----V —

Cit y of B ir m in g h a m .

Appeal from Jefferson Circuit Court

January 25, 1963

Transcript Filed

April 18, 1963

Come the parties by attorneys, and submit this cause on

briefs for decision.

November 19, 1963

Come the parties by attorneys, and the record and mat

ters therein assigned for errors, being submitted on briefs

and duly examined and understood by the court, it is con

sidered that in the record and proceedings of the Circuit

Court there is no error. It is therefore considered that the

judgment of the Circuit Court be in all things affirmed. It

is also considered that the Appellant pay the cost of appeal

of this court and of the Circuit Court.

7a

Order o f Alabama Court o f Appeals Denying Rehearing

January 7, 1964

It is ordered that the application for rehearing be and

the same is hereby overruled.

Per Curiam.

8a

Orders of the Supreme Court of Alabama

T h e S uprem e Court of A labama

Thursday, February 20, 1964

The Court Met Pursuant to Adjournment

Present: All the Justices

6th Div. 65

Ex Parte: Fred L. Shuttlesworth

P etition for W rit of Certiorari to C ourt of A ppeals

(Ee: Fred L. Shuttlesworth vs. City of Birmingham)

Jefferson Circuit Court

Come the parties by attorneys and the Petition for Writ

of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals being submitted on

briefs and duly examined and understood by the Court, it

is considered and ordered that the Writ be and the same

is hereby denied and the petition dismissed at the cost of

the petitioner, for which costs let execution issue accord

ingly.

No Opinion.

9a

Thursday, March 26, 1964

T h e S uprem e C ourt of A labama

Thursday, March 26, 1963

The Court Met Pursuant to Adjournment

Present: All the Justices

6th Div. 65

Ex Parte: Fred L. Shuttlesworth

P etition for W rit of Certiorari to C ourt of A ppeals

(Re: Fred L. Shuttlesworth vs. City of Birmingham)

Jefferson Circuit Court

I t I s Ordered that the application for rehearing filed in

the above styled cause on March 6, 1964, be and the same

is hereby overruled.