Motion for Further Proceedings on Remand; Supplemental Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees Supporting Motion

Public Court Documents

May 18, 1980

33 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Motion for Further Proceedings on Remand; Supplemental Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees Supporting Motion, 1980. 68c39d86-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/945fb5e1-61ff-4641-9b8b-2ac1071a92ac/motion-for-further-proceedings-on-remand-supplemental-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellees-supporting-motion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

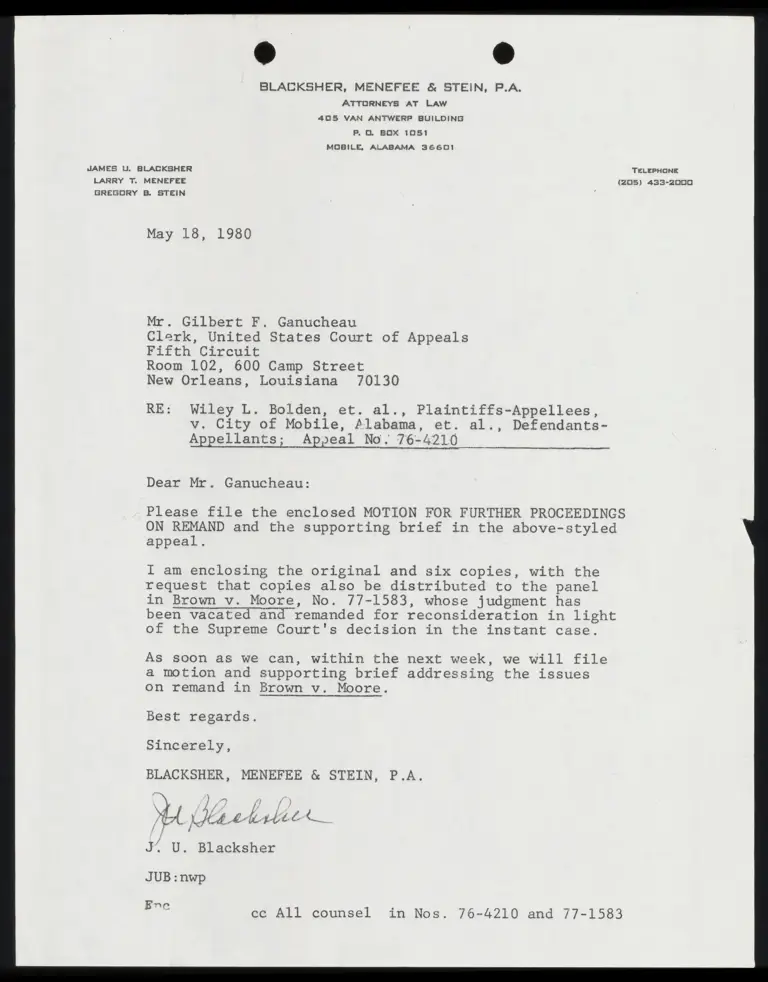

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT Law

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

P. O. BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36601

JAMES LU. BLACKSHER TELEPHONE

LARRY T. MENEFEE (205) 433-2000

GREGORY B. STEIN ’

May 18, 1980

Mr. Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Clerk, United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

Room 102, 600 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

RE: Wiley L. Bolden, et. al., Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v. City of Mobile, Alabama, et. al., Defendants-

Appellants; Appeal No. 76-4210

Dear Mr. Ganucheau:

Please file the enclosed MOTION FOR FURTHER PROCEEDINGS

ON REMAND and the supporting brief in the above-styled

appeal.

I am enclosing the original and six copies, with the

request that copies also be distributed to the panel

in Brown v. Moore, No. 77-1583, whose judgment has

been vacated and remanded for reconsideration in light

of the Supreme Court's decision in the instant case.

As soon as we can, within the next week, we will file

a motion and supporting brief addressing the issues

on remand in Brown v. Moore.

Best regards.

Sincerely,

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

MA (ft ert et_

J. U. Blacksher

JUB :nwp

Ere

cc All counsel in Nos. 76-4210 and 77-1583

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-4210

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET. AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

V.

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, ET. AL.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama, Southern Division

MOTION FOR FURTHER

PROCEEDINGS ON

REMAND

Plaintiffs-Appellees Wiley L. Bolden, et. al., through

their undersigned counsel, move for the institution of fur-

ther proceedings on remand, as is more fully set out in this

motion and the supporting brief, and for leave to file these

supporting briefs, pursuant to Rule 27, FRAP, and Rule

10.1.12, Fifth Circuit rules.

As grounds for their motion, Plaintiffs-Appellees

would show that, on April 22, 1980, the Supreme Court of

the United States reversed the judgment of this Court and

remanded the case for further proceedings in the courts

below. City of Mobile wv. Bolden, 48 USLW 4436 (Apr. 22, 1980).

For reasons which are more fully set out in the sup-

porting brief filed contemporanously herewith, further

proceedings are required to determine whether at-large

elections have been retained in the City of Mobile for

reasons which violate the rights of black citizens under

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the constitution

of the United States and under the Voting Rights Act

of 1965,

WHEREFORE plaintiffs-appellees pray that this Court

will:

A. Grant them leave to file the supporting brief

filed contemporaneously with this motion;

B. Remand this case to the district court for

further proceedings, including the taking of such addi-

tional evidence as the district court deems warranted,

to determine whether Mobile's at-large election system

has been retained for a racially discriminatory purpose,

to determine whether a private cause of action is avail-

able under §2 of the Voting Rights Act and, if so

whether Plaintiffs' rights thereunder have been violated H

and to reexamine its remedial order in light of Wise v.

Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978).

In the alternative, if the case is not first

remanded to the district court, Plaintiffs-Appellees

pray that, on the basis of the evidence already in the

record, this Court will enter a judgment affirming in part

and vacating in part the judgment of the district court

and remanding the case for further proceedings as follows:

(1) Reaffirming the judgment of the district

court that at-large elections have been retained in the

City of Mobile, at least in part, for the purpose of di-

luting the voting strength of the black minority;

(2) Reaffirming the judgment of the district

court that, accordingly, the current at-large election

system for the City of Mobile violates the rights of

black citizens of Mobile under the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments to the Constitution of the United

States;

(3) Further holding that Mobile's present

election system violates. §2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 and that Plaintiffs-Appellees are afforded a

private cause of action to enforce the statutory rights;

(4) Remanding the case to the district court

for reconsideration of its remedial order in light of

Wise v. Lipscomb, and for such other additional proceedings

as it may deem equitable and just.

To 4

Respectfully submitted this /§ “day of May, 1980.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

POST OFFICE BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36601

EDWARD STILL

Reeves & Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this /9%4ay of May,

1980, a copy of the foregoing MOTION FOR FURTHER

PROCEEDINGS ON REMAND was served upon counsel of record:

Charles B. Arendall, Jr., Esquire, William C. Tidwell, III,

Esquire, Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, Greaves & Johnson, Post

Office Box 123, Mobile, Alabama 36601; Fred G. Collins,

Esquire, City Attorney, City Hall, Mobkle, Alabama 36602;

Charles S. Rhyne, Esquire, William S. Rhyne, Esquire,

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N. V., Suite 800, Washington,

D.C. 20036, by depositing same in the United States Mail,

postage prepaid.

7 7 D aici SBT ATNTTFFS-APPELLEES

)

NY LLL ) NLS LAL a

/ log / ; MH O.24

/ A

f +4

7 3

Vv

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-4210

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET. AL

LE

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, ET. AL.,

Defendants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Alabama, Southern Division

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

SUPPORTING MOTION FOR ADDITIONAL PROCEEDINGS

ON REMAND

EDWARD STILL

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

J. U. BLACKSHER

LARRY T. MENEFEE

P. O. Rox 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36601

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

What the Supreme Court's Decision

Means

In retrospect, it is clear that the Supreme Court

took this case in order to overrule Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973), aff'd sub nom., East Carroll

Parish School Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976). Some

members of the Court had expressed disappointment over

avoiding a head-on confrontation with the Zimmer merits on

at least two previous occasions, in East Carroll Parish,

supra, and in Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535, 549 (1978)

(J. Rehnquist, concurring). Not to be denied a third time,

the Supreme Court's plurality insisted on reading the

opinions of this Court znd the district court in the

instant case as having relied solely on a Zimmer analysis

of the evidence.

Thus, because the appellees had

proved an "aggregate' of the

Zimmer factors, the Court of

Appeals concluded that a discrim-

inatory purpose had been proved.

That approach, however, is incon-

sistent with our decisions in

Washington v. Davis, supra, and

Arlington Heights, supra. Although

the presence of the indicia relied

on in Zimmer may afford some evi-

dence of a discriminatory purpose,

satisfaction of those criteria is

not of itself sufficient proof of

such a purpose. The so-called

Zimmer criteria upon which the

District Court and the Court of

Appeals relied were most assuredly

insufficient to prove an unconsti-

tutionally discriminatory purpose

in the present case.

48 USLW at 4441. So, in order to isolate the Zimmer

inquiry, the plurality chose to ignore the substantial

additional evidence in this record of an invidious legis-

lative purpose in retaining at-large elections, and they

remanded the case back to this Court for further consi-

deration of whether such intent "ultimately' can be proved.

Id. at 4441 n. 21; accord, id. at 4449 (J. White, dissenting),

4459 n. 39 (J. Marshall, dissenting). Although Justice

White complained that the plurality has "[left] the courts

below adrift on unchartered seas with respect to how to pro-

ceed on remand," id. at 4449, careful scrutiny of the

several opinions, particularly the Stewart plurality's,

does provide workable guidance.

Simply put, Bolden holds that an invidious racial

motive on the part of those who control legislation must

be proved to invalidate an at-large election plan under the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments and that the Zimmer

standards do not, by themselves, establish the requisite

intent. To discern this result and the subsidiary holdings

of Bolden, one must “headcount” each issue through the

six opinions of the Justices:

(1) The Equal Protection Clause of the

fourteenth amendment provides a cause of action for dilu-

tion of blacks' voting strength. 48 USLW at 4439 (Stewart);

id. at 4444 (Stevens); id.at 4449 (White); id. at 4443

(Blackmun); id. at 4444 (Brennan); id. at 4449 (Marshall).

(2) Dilution can also violate the

fifteenth amendment. 48 USLW at 4444 n. 3 (Stevens); id.

at 4449 (White); id. at 4443 (Blackmun); id. at 4446

(Brennan); id. at 4449 (Marshall). The plurality’'s view

that the fifteenth amendment goes no further than guaranteeing

the right to register and vote, id. at L438, was rejected

by the rest of the Court.

(3) But an invidious legislative purpose

to discriminate in either the enactment or retention of the

at-large scheme must be proved under both the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments. 48 USLW at 4438, 4439 (Stewart);

id. at 4448 (White); id. at 4445 (Stevens).

(4) The Zimmer analysis is overruled as

a sufficient measure, by itself, of a constitutional violation.

48 USLW at 4441 (Stewart); id. at 4445 (Stevens).

However, there is no majority view in Bolden about

the proper legal test for proving invidious intent or,

as a corollary matter, why Zimmer is unsatisfactory as a

constitutional test. Justice White believes that an

aggregate of the Zimmer factors proves racial intent by

a "totality of circumstances" approach (the approach used by

this Court in Bolden). 48 USLW at 4449. Justices Blackmun,

Brennan and Marshall agree. Id. at 4443, 4446, 4458.

Justice Stevens would require objective proof that the

election plan was either totally irrational or motivated

solely by racial reasons. Id. at 4445. The Stewart

plurality would apply the guidelines of Arlington Heights

and Personnel Adm'r of Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

* 7256 (1979), but would focus more on the subjective intent

of lawmakers than the way the system operates. According

to the plurality, "Zimmer may afford some evidence of a

discriminatory purpose [but] is not of itself sufficient

proof of such a purpose." 48 USLW at 4441.

Five Justices were of the opinion that the Zimmer

approach used by this Court in Bolden did prove racial

motives in the maintenance of Mobile's election system

(Stevens, Blackmun, White, Brennan and Marshall). But one

of the five, Stevens, thinks that more is required to

prove a constitutional claim. It seems clear, therefore,

that to prove a case of intentional vote dilution that

satisfies a majority of the Supreme Court, the demands of

the Stewart plurality must be met.

The holding of the Bolden plurality is "that the

primary, if not the sole, focus of the inquiry must be on

the intent of the political body responsible for making

the districting decision.” 48 USLW at 4445 (Stevens,

concurring). See id. at 4440. The requisite intent must

be discerned in the evidence by use of the legal principles

of Washington ¥v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976); Arlington

Heights, supra; and Feeney, supra. Id. at 4438 n. 10,

% 4439, 4440, 4441; accord, id. at 4458 (Marshall, dissenting).

Those principles can be summarized as follows:

(1) The impact of the districting plan

-- whether it bears more heavily on one race than on

another -- provides a starting point. Arlington Heights,

supra, 429 U.S. at 266. Thereafter, "a sensitive inquiry"

should be made into the following types of evidence:

(2) The historical background of the

legislative decision, ''particularly if it reveals a series

of official actions taken for invidious purposes." Id. at

267.

(3) The "specific sequence of events"

leading up to the decision. Sudden changes that counter-

act . events favoring the minority group can show invidious

intent. 1d.

(4) 'Departures from the normal procedural

sequence’. 1d.

(5) '"Substantive departures . . . parti-

cularly if the factors usually considered important by

the decisionmaker strongly favor a decision contrary to

the one reached." 1d.

(6) The legislative history, especially

contemporary statements by lawmakers, their minutes and

AS reports. "3d. at 268. 7

(7) The trial testimony of those

involved in the decision making process. Id.

Feeney has been interpreted as adding a substantial

gloss to the Washington v. Davis - Arlington Heights prin-

ciples:

"Discriminatory purpose,’ how-

ever, implies more than intent as

volition . or intent as awareness of conse-

quences. It implies that the decision

maker, in this case a state legislature,

selected or reaffirmed a particular

course of action at least in part

"because of," not merely "in spite of,"

its adverse effects upon an

identifiable group.

Feeney, supra, 60 L.Ed. 2d at 887-88 (citation and

footnotes omitted). But this Feeney rule does nothing

more than reject as a complete measure of constitutional

intent mere "awareness of consequences" or "foreseeability"

standing alone .L/ Justice Stewart hastened to explain in

Feeney that this does not mean that "inevitability or

foreseeability of consequences of a neutral rule has

no bearing upon the existence of discriminatory intent."

60 L.Ed. at 888 n. 25. Indeed, the record in that case

showed that "all of the available evidence affirmatively

demonstrate[d]" that Massachusetts' veterans preference

had a completely benign purpose. Id. (emphasis added).

The same was far from true in Bolden, which is why,

we submit, the case was remanded for further proceedings

ir. the courts below.

1/ Justice Marshall thinks even this limited constraint

on intent findings is ''far too extreme to apply in

vote-dilution cases." Bolden, supra, 48 USLW at 4458. He

would have adopted the "common-law foreseeability pre-

sumption" that at least shifts the burden of disproving

invidious intent to the state. Id. But most observers are

not surprised that the same rule applied in "Austin II",

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 532 F.2d 380

(5th Cir.), vac. and remanded, 429 U.S. 990 (1976), on

remand, 564 F.2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977), on rehearing, 579

F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978), has now been extended to all

fourteenth amendment cases.

7

Further, the Bolden plurality's adoption of Feeney

underscores their repudiation of Justice Stevens' proposal

that in apportionment cases an invidious purpose must be

the sole motive behind the legislative decision. Justice

Stewart's majority opinion in Feeney could not state the

constitutional rule more plainly:

Invidious discrimination does

not become less so because the

discrimination accomplished is

of a lesser magnitude. Discrimi-

natory intent is simply not amen-

able to calibration. It either

is a factor that has influenced

the legislative choice or it is

not.

60 L.Ed. 2d at 886 (footnote omitted). Feeney set up

K "a twofold inquiry" for facially neutral laws that adversely

impact on a minority group: (1) Is the neutral rule

actually an overt or covert pretext for invidious discrimi-

nation? (2) If not, then the 'dispositive question"

is whether an invidiously discriminatory purpose has,

"at least in some measure,' shaped the rule. 60 L.Ed 2d

at 884-85. Justice Stevens' theory in Bolden would per-

mit only the first of the Feeney inquiries when analyzing

apportionment decisions and not the second. Clearly, his

extreme view has no support among the other members of

the Court. Justice Powell's majority opinion in Arlington

Heights states the Supreme Court's rule:

[Washington v.] Davis does

not require a plaintiff to prove

that the challenged action rested

solely on racially discriminatory

purposes. Rarly can it be said

that a legislature or administrative

body operating under a broad mandate

‘made a decision motivated solely

by a single concern, or even that

a particular purpose was the

"dominant" or "primary' one. In

fact, it is because legislators

and administrators are properly

concerned with balancing numerous

competing considerations that

courts refrain from reviewing the

merits of their decisions, absent

a showing of arbitrariness or

irrationality. But racial discrimi-

nation is not. just another competing

consideration. When there is proof

ak oe that a-discriminatory purpose has

$ been a motivating factor in the

decision, this judicial deference

is no longer justified.

Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 265-66 (footnotes

omitted).

" The Proceedings on Remand

The Supreme Court's mandate in Bolden states: ''The

judgment is reversed and the case is remanded to the Court

of Appeals for further proceedings." 48 USLW at 4443. Our

Supreme Court brief and oral argument contended that both

this Court and the district court had looked beyond Zimmer

. jo

and had made Arlington Heights findings of a racial

intent in the maintenance of at-large elections based

on the testimony of local lawmakers. But, as we have

already pointed out, pp. 1 - 2, supra, the plurality in-

sisted on reading the opinions below as based solely on

a Zimmer analysis. When Justice Stewart wrote "it is clear

that the evidence in the present. case fell far short of

showing that the appellants 'conceived or operated [a]

purposeful device[ ] to further racial discrimination',"

48 USLW at 4440, he was referring only to'[t]he so-called

Zimmer criteria upon which the District Court and the

Court of Appeals relied ...." Id. at 4441. The plurality

expressly left open for further consideration on remand

the black Plaintiffs’ claims that modern-day legislative

proposals to give Mobile single-member district options

had been repudiated for racial reasons.

There was evidence in this case

that several proposals that would

have altered the form of Mobile's

municipal government have been de-

feated in the state legislature, in-

cluding at least one that would have

permitted Mobile to govern itself

through a mayor and city council

with members elected from individual

districts within the city. Whether

it may be possible ultimately to

prove that Mobile's present govern-

mental and electoral system has been

-10-

pl retained for a racially dis-

criminatory purpose, we are

in no position now to say.

Id. at 4441 n. 21 (emphasis added). Two other opinions

support this interpretation of the plurality's remand

instructions. Justice White acknowledged that the lower

courts would be required to reexamine the intent question,

but complained that they had been set "adrift on uncharted

seas". Id. at 4449. Justice Marshall provided the most

explicit statement of the remand task:

The plurality, ante, at 18,

n.2l, indicates that on remand

the lower courts are to examine

the evidence in these cases under

the discriminatory intent standard

of Personnel Adm'r of Mass. wv.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979), and

rey may conclude that this test is met

% by proof of the refusal of Mobile's

state-legislative delegation to

stimulate the passage of legislation

changing Mobile's city government

into a mayor-council system in which

council members are elected from

single-member districts. The

plurality concludes, then, only that

the District Court and the Court of

Appeals in each of the present cases

evaluated the evidence under an

improper legal standard, and not that

the evidence fails to support a claim

under Feeney, supra.

48 USLW at 4459 n. 39.

Thus on remand this Court may yet affirm the judgment

of the district court if the requisite racial intent of the

& lawmakers appears from the evidence under the Arlington

Heights - Feeney legal standards that now govern dilution

cases .2/ Notwithstanding the Bolden plurality's inability

to see it, we believe this Court in fact already reached

such a conclusion using an Arlington Heights analysis on

the first go-round. In the next section of this brief

we will summarize the facts that warrant reaffirmance of

the findings of invidious legislative intent.

However, with due respect and out of an abundance

of caution, we urge this Court to remand the question to

the district court first. The Supreme Court has instructed

the appellate courts reviewing Arlington Heights cases

® to give special deference to the fact finding of the

district judge "who has lived with the case over the years,"

2/ Such a result would be consistent with the general

~ rule that, "[w]hile a mandate is controlling as to

matters within its compass, on remand a lower court

is free as to other issues." Sprague v. Ticonic Nat'l

Bank, 307 U.S. 161, 168 (1939). An example close on

point here is Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974),

which held that retroactive welfare benefits awarded by

a district court violated the eleventh amendment. The

Court's remand stated: '"The judgment of the Court of

Appeals is therefore reversed and the cause remanded for

further proceedings consistent with this opinion."

415 U.S. at 679. On remand the Court of Appeals ordered

Illinois officials to notify all class members of state

law procedures that would afford them similar monetary

relief. 563 F.2d 873. It rejected the state's contention

mb

®

676, n.6 (1979) (J. White), and who is "uniquely situated

++. to appraise the societal forces at work in the

communit[y] where [he] sit[s].” "Id. at 685 (J. Stewart);

accord, id. at 683 (J. Burger). Here the controlling

plurality professed uncertainty about the meaning of the

district court's key language concerning "intentional

state legislative inaction”. 48 USLW at 4440 n. 17.

They believed the trial judge might have been relying

on theories of jury discrimination cases or purely fore-

seeable consequences. Id. Somehow, they were unable

to associate the district court's intentional inaction

conclusion with the legislative intent evidence later

discussed in the plurality's footnote 21. Under these

Footnote 2/ continued

that such relief was contrary to the law of the case

as established by the Supreme Court in Edelman. In a

second appeal, the Supreme Court affirmed, saying:

The doctrine of law of the case

comes into play only with respect

to issues previously determined.

In re Sanford Fork & Tool Co.,

160 U.S. 247 (1895). On remand,

the "Circuit Court may consider

and decide any matters left open

by the mandate of this court."

Id. at 256,

Quen v. Jordan, 99 S.Ct. 1139, 11483 n. 18 (1979).

13+

circumstances, this Court might be well advised not

to presume (again) from the district court's opinion

what the Supreme Court was unable (or unwilling) to

read there. The district judge should be asked to

clarify his findings in light of the Supreme Court's

decision -- and to receive such additional evidence as

-..3

he deems warranted.

The Present Record Proves Racial

Motives in the Retention of Mobile's

At-large Election Plan

In the alternative, if this Court addresses the

issue remanded by the Supreme Court without first referring

it to the district cours, the present record already

3/ Remand to the district court has been the usual prac-

tice of this Court when intervening Supreme Court de-

cisions have changed the legal theory relied on originally

by the trial judge; in particular where proof of discrimi-

natory intent replaces an earlier theory based on discrimi-

natory effect. Williams v. DeKalb County, 582 F.2d 2

(5th Cir. 1978); Concerned Citizens of Vicksburg v. Sills,

567 F.2d 646 (5th Cir. 1978); Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp.

556. F.24 758 {5th Cir. 1977).

4/ Even if the case is sent back to the district court,

this Court should provide some guidance concerning

the proper application to these facts of the Supreme Court's

divergent opinions in Bolden.

3

establishes the inescapable conclusion that modern-day

decisions of the legislature were designed to strengthen

and preserve the City of Mobile's election scheme for the

purpose of denying blacks representation.

The decision regarding what forms of government and

districting plans will be available to Mobile has always

been controlled exclusively by the Mobile County legis-

lative delegation, which operates under a local courtesy

custom permitting any one of the county's senators to

veto local bills. 423 F.Supp at 397. Since Mobile

adopted a city commission form of government in 1911,

local legislators have acted progressively to enhance

the dilutive impact of the at-large scheme and to deny

even the opportunity for referendum changes to single-

member districts. The most important of these legislative

decisions were (1) a 1945 amendment which removed the

original plurality-win feature of commission elections,

(2) an annexation in 1956 that tripled the geographic

size of the City of Mobile, (3) a local law in 1965 that, at

once, attached executive functions to the three commissioner

places and offered a mayor-council option that preserved

at-large elections, and (4) a mayor-council bill containing

a mixed at-large and district election plan that was vetoed

-15~

— in 1976 by one white senator. These events must be

viewed together in their historical context, as Arlington

Heights directs.

- Throughout the nineteenth century Mobile used the

mayor-alderman option provided in general state law. Ala.

Code. §11-43-40 (1975) .2/ In 1911, the city commission

form was adopted under ''race-proof" circumstances. 571

F.2d at 245.8 However, as originally enacted, the 1911

law provided that the voters would designate a first and

second choice for each commissioner, with the candidate

receiving a majority of the first-choice votes or the

majority of first-choice and second-choice votes winning.

® Act 281, Ala. Acts, 1911 Reg. Sess. After the election,

the commissioners were to choose one of their number as

mayor and divide other executive duties among all three.

Act 281, supra, §§ 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11.

5/ Mobile presently has 31 wards. If it reverted to this

mayor-alderman government today, Mobile would be required

by §11-43-40 to reduce the number of wards to no more than 20,

with one alderman elected by the voters of each ward plus

a mayor and council president elected at large.

6/ Blacks were almost totally disfranchised in Alabama

by the 1901 state constitution.

1b

For the next 35 years, the white-only Democratic

primary and restrictive registration laws (e.g., the poll

tax, literary tests) kept blacks from registering to vote.

Then the Supreme Court struck down the white primary.

Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944). Alarmed, the

Alabama Democratic Party responded to Smith v. Allright

and to post-war black voter registration drives in Mobile,

P. Ex. 2, by sponsoring the Boswell gnendasre which

required registrants to "understand and explain" the U.S.

Constitution. The Boswell Amendment was later determined

to have been a contrivance to bar blacks from registering.

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (5.D. Ala.), aff'd,

- T7336 U.S. 933 (1949). Id the midst of this flurry of

official action to safeguard white supremacy, the city

commission act was amended to eliminate the possibility

of a plurality winner by adding numbered posts and a

ma jority - vote requirement. Act 295, Ala. Acts, 1945

Reg. Sess., p. 490.

7/ There were only 275 placks registered in Mobile

County in 1946." P, Ex. 2,

8/ Ala. Const., amend no. 35 (1946).

9/ It is noteworthy that the leadership for the Boswell

Amendment came from a Mobile politician. P. Ex. 2.

The black registration rate in Mobile County

continued to grow. By the mid - '50's it was around

147%. P. Ex.7. At the same time, many whites were moving

to the suburbs outside the Mobile city limits. In 1956,

the local legislative delegation passed a bill annexing

the white suburbs to the city. Act 18, Ala. Acts, 1956

2d Extra Sess. Without this annexation, Mobile would have

been 54% black by 1970.2". The annexation cleared the

legislature at a time when it was consumed with open con-

cern over desegregation in general and pending federal

legislation aimed at opening the voting booth to blacks

in particular of

10/ United States Census, City-County Data Book, p. 630

(1972); Mobile Register, Mar. 2, 1956, p. 1A.

11/ 1In 1956, the Eisenhower Administration was pressing

for passage of what eventually became the Civil Rights

Act of 1957. Special sessions of the Alabama Legislature

were called to preserve the state's segregationist policies

in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954). Proposed constitutional amendments were enacted

to authorize legislation establishing private, racially

segregated schools, recreational and other public facilities.

No. 82, Ala. Acts, 1956 lst Extra Sess.; No. 67, Ala. Acts,

1956 2d Extra Sess. Resvlutions were adopted denouncing

Brown itself and proclaiming Alabama's ''deep determination"

to preserve its long established discriminatory policies.

No. 58, Ala. Acts, 1956 2d Extra Sess. See United States

v. Alabama, 252 F. Supp 95, 102 (M.D. Ala. 1966). A year

later, Montgomery County changed to at-large elections for

what Judge Johnson recently determined were racial reasons.

Hendrix v. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626 (M.D. Ala. 1978).

-18~

With the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

the remaining impediments to black voter registration

were removed, and approximately 257% of eligible black

Mobilians were registered to vote. Tr. 355. At this

time, the local delegation adopted Act No. 823, Ala. Acts,

1965 Reg. Sess., which on one hand predesignated the exec-

utive roles of each Mobile city gomissionai® and on the

other authorized a referendum on changing to a mayor-council

form of government. However, Act 823 specified that all

the council members would be elected at large. P. Ex. 98,

pp. 40-41. Former Senator Edington, then a member of

Mobile's local legislative delegation, gave undisputed

testimony that the lawmakers considered and rejected

single-member districts for the council option because of

racial reasons:

Q. Why was the opposition to single-

member districts so strong?

A. At that time, the reason argued

in the legislative delegation, very simply

was this, that if you do that, then the

public is going to come out and say that

the Mobile legislative delegation has just

passed a bill that would put blacks in

city office. Which it would have done

had the city voters adopted the mayor-

council form of government.

P. Ex, 98. p. 43.

12/ 8See 571 F.2d at 241 n.2.

16

Finally, in 1976, State Senator Bill Roberts of

Mobile introduced a local bill which would have given

Mobilians the option of changing by referendum to a

mayor-council form, with seven council members elected

from districts and two at large. Tr. 727-28. Senator

Roberts testified that he had publicly announced his

reasons for the bill, that he had introduced it in re-

sponse to ehis Aictgar tod ana to provide blacks an

opportunity to be represented in city government. Tr.

729, 733, 734. The bill was vetoed by another white

14/

senator, Mike Perloff oberts said Perloff had given

no reason for his veto. When asked if he knew why,

~Roberts testified: "Yes. I have some idea, but I

cannot prove that." Tr. 736. However, the two black

Mobile County legislators, Cain Kennedy and Gary Cooper,

had no doubt that the Roberts Bill was killed to

13/ "I did make the statement that I felt that too often

in Alabama ... the legislature has not met its responsi-

bility and in those situations the courts have moved into

that area because of the lack of responsibility of the

legislature." Tr. 733.

14/ Senator Perloff had narrowly defeated a black candi-

~~ date in a senate district almost 50% black, using racial

campaign tactics. See Brown v. Moore, No. 75-298-P

(S.D. Ala., Jan. 18, 19773, Op. at 9, No. 77-1583 (5th Cir.)

Appendix p. 233.

blacks from being elected. P. Ex. 100, pp. 29-30;

P. Ex. 99, p. 20.

This series of legislative actions from 1945 to

1976 provide a "sequence of events" set against an

historical background of official racism, accompanied by

procedural and substantive departures, all combining to

produce a severely adverse impact on black voters. - The

circumstantial evidence is cemented by direct testimony

by lawmakers of invidious motives. Nearly all of the

Arlington Heights criteria are satisfied. Nor is this

like the situation in Feeney, where the state had attempted

to relieve the impact of its otherwise benign policies

on the disadvantaged group, 60 L.Ed. 2d at 881, and where

"all of the available evidence affirmatively demonstrate[d]"

there was no discriminatory intent. 1d. at 838 n. 25. At-

large elections have been retained in Mobile "because

of, not in spite of", their dilutive effects. For sure,

"goodgovernment" =2/ reasons were espoused by some of the

lawmakers at several stages of the legislative history

of Mobile's election system. Under Arlington Heights and

Feeney, such "mixed motives' do not save the racially

intended laws from constitutional invalidity. See pp.8-9,6 supra.

15/ Flannery O'Connor, "The Barber,' The Complete Stories 153,

20 (1979).

-J1-

® And the racial motives cannot be missed. To use Judge

Rives' familiar phrase, for the courts to conclude

otherwise would "prove that justice is both blind and

deaf." United States v. Alabama, 252 F., Supp. 95, 104

(M.D. Ala. 1966), quoting, Sims v. Baggett, 247 F. Supp.

96, 108-09 (M.D. Ala. 1965).

The Voting Rights Act Claim

The Supreme Court's decision in Bolden leaves open

the question whether a private cause of action lies

under §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and, if so,

~~what elements of proof §2 requires to challenge dilutive

® election schemes. Only the plurality opinion discusses

the statutory issue. It criticizes this Court's refusal

to address Bolden's §2 claim, but goes on to conclude

that, even if a private cause of action exists, §2 "was

intended to have an effect no different from that of the

Fifteenth Amendment itself." 48 USLW at 4437. None of

the other opinions even acknowledges this discussion.

At the very least, the district court should be

instructed on remand not to ignore the plurality's admoni-

tion to rule on the §2 claim. (Alternatively, if this Court

» decides the intent issue without first remanding to

the district court, it should take up the §2 claim.)

If the district judge determines in subsequent proceedings

that Mobile's at-large elections are being maintained for

a racial purpose, it need only decide whether a private

cause of action exists under. §2, and there will be no

need for it to pass judgment on the dispute left open by

the Supreme Court about whether. §2's substantive scope

exceeds that of the fifteenth amendment. On the other

hand, it will be necessary for the district court to

decide whether §2 of the Voting Rights Act provides an

effect-only standard if it is determined the election

% plan is not racially motivated. This Court's remand

instructions should specify the trial court's responsibi-

lities in this regard.

The Remedy Issue

Justice Blackmun was the only member of the Court

who questioned the apprcpriateness of the district court's

remedy, that is, ordering a change in the form of government

in order to provide for single-member districts. 48 USLW at

4443. It seems clear, however, that on remand the district

33

.

court should be instructed to reconsider its remedial

order in light of the Supreme Court's intervening

decision in Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978).

- Conclusion

Pursuant to the mandate of the Supreme Court,

this Court should remand the case immediately to the

district court with instructions that it conduct additional

proceedings, taking such additional evidence as the court

deems necessary, in order to determine whether the City

of Mobile's at-large elections have been retained for a

“racially discriminatory purpose.

Alternatively, this Court should conclude on the

basis of the evidence already in the record that such

irvidious intent has been proved.

The remand instructions of this Court should further

direct the district court:

(1) To determine whether Plaintiffs have

a private cause of action under §2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 and, if so, whether the statutory claim has

been proved; and

2h

(2) To reexamine its remedial order in light

of Wise v. Lipscomb.

Respectfully submitted this | ¥“% day of May, 1980.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

POST OFFICE BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36601

BY . ' Af A { IAP 4 & Pd / pr - ,

J./ U. BLACKSHER"

LARRY T. MENEFEE

/ /

& /

1}

EDWARD STILL

REEVES & STILL

SUITE 400, COMMERCE CENTER

2027 FIRST AVENUE, NORTH

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

«25.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this /87 day of May,

1¢80, a copy of the foregoing SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES SUPPORTING MOTION FOR ADDITIONAL

PROCEEDINGS ON REMAND was served upon counsel of record:

Charles B. Arendall, Jr., Esquire, William C. Tidwell, III

Esquire, Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, Greaves & Johnson,

Post Office Box 123, Mobile, Alabama 36601; Fred G.

Cullins, Esquire, City Attorney, City Hall, Mobile,

Alabama 36602; Charles S. Rhyne, Esquire, William S.

Rhyne, Esquire, 1000 Connecticut Avenue, N. W., Suite

800, Washington, D. C. 20036, by depositing same in the

United States Mail, postage prepaid.

—

“26