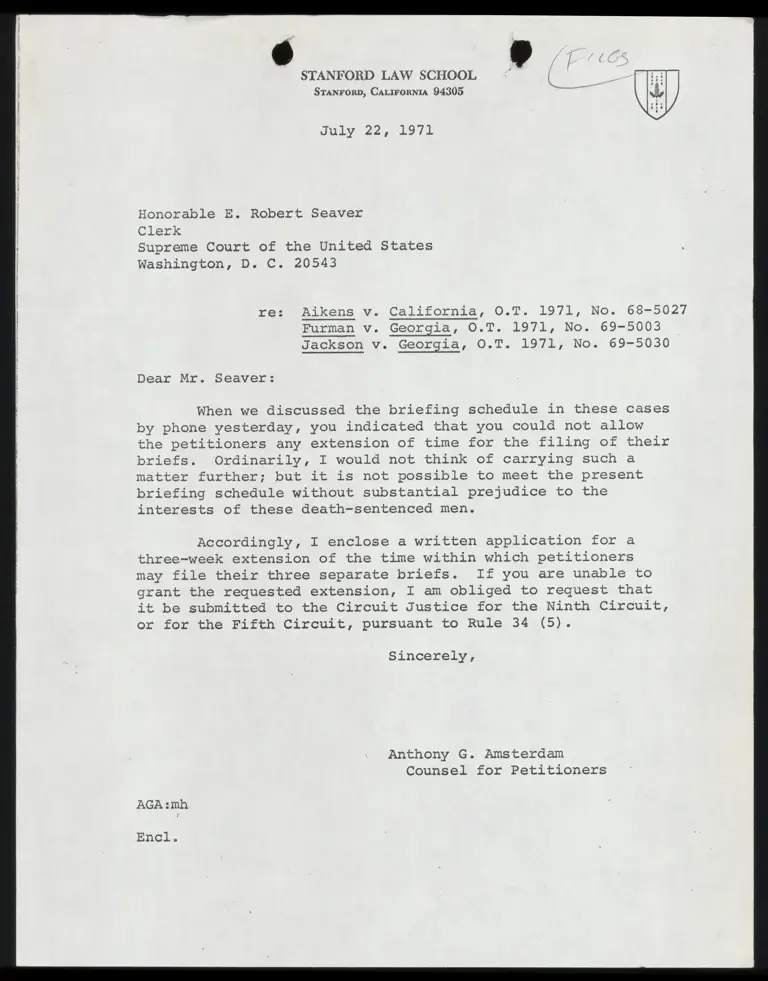

Correspondence from Amsterdam to Clerk; Application for Extension of Time for Filing Petitioners' Briefs

Correspondence

July 22, 1971

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Correspondence from Amsterdam to Clerk; Application for Extension of Time for Filing Petitioners' Briefs, 1971. 6789a70c-b325-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/948303d7-e101-4205-8788-7915ecf0cc6e/correspondence-from-amsterdam-to-clerk-application-for-extension-of-time-for-filing-petitioners-briefs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

STANFORD LAW SCHOOL °° C

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA 94305

July 22, 1971

Honorable E. Robert Seaver

Clerk

Supreme Court of the United States

Washington, D. C. 20543

re: :Aikens v. California, 0.7. 1971, No. 568-5027

Furman v. Georgia, O0.T. 1971, No. 69-5003

Jackson v. Georgia, O.T. 1971, No. 69-5030

Dear Mr. Seaver:

When we discussed the briefing schedule in these cases

by phone yesterday, you indicated that you could not allow

the petitioners any extension of time for the filing of their

briefs. Ordinarily, I would not think of carrying such a

matter further; but it is not possible to meet the present

briefing schedule without substantial prejudice to the

interests of these death-sentenced men.

Accordingly, I enclose a written application for a

three-week extension of the time within which petitioners

may file their three separate briefs. If you are unable to

grant the requested extension, I am obliged to request that

it be submitted to the Circuit Justice for the Ninth Circuit,

or for the Fifth Circuit, pursuant to Rule 34 (5).

Sincerely,

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Counsel for Petitioners

AGA :mh

Encl.

Honorable E. Robert Seaver 2. July 22, 1971

cc: Honorable Evelle J. Younger

Attorney General

600 State Building

Los Angeles, California 90012

Attention: Ronald George, Esq.

Deputy Attorney General

Honorable Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

132 State Judicial Building

40 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

Attention: Dorothy Beasley, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

#]

$

QQ

1

C4

4}

Q ¥ Ga

James M,

Eat widen. :

Jack Himmelstein,

-~

Xe

sreenberg, Esq. ho od

M. Nabrit III, Es

4 BE

erome B. Falk, Jr., Esq.

¥

Sq.

1 IN THE

; SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

3S

October Term, 1971

Nos. 68-5027, 69-5003, 695-5030

7

8 EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

9 Petitioner,

10 oyu a No. 68-5027

31 rE ER FYA Wy §

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

N

e

?

d

N

”

Na

t’

S

a

a

”

N

o

S

m

t

”

S

a

a

S

N

”

2

Regpondent. y

13

14 T

15 )

16 WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN, )

)

17 Petitioner, )

18 - Ne - ) Ro. 69-5003

QO Ti “A HN = T3 TANYA T 19 I! STATE OF GEORGIA, )

2 2

0 Respondent. )

21

22

23 )

LUCIOUS JACKSON ; Ey A 4

4 ly oe )

or Petitioner, ) $

26 FV ) No. 69-5030

<7 | STATE OF GEORGIA, )

| ) |

I's il

> § | R STC OCT LL. )

29 ;

er)

30

i

31 APPLICATION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

FOR FILING PETITIONERS' BRIEFS f

a

|]

|

|

|

|

|

Lp)

a

(O

F

6

7

5

te J

"rey

WF

Petitioners respectfully apply for an extension of three

weeks time, until September 2, 1971, to file their briefs in

these cases. The extension is necessary for the following

reasons:

(1) Certiorari was granted in each of these three cases

on June 28, 1971, on the question:

"Does the imposition and carrying out

of the death penalty in this case

constitute cruel and unusual punish-

ment in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments?"

This common constitutional question is presented upon quite

different records in the three cases, two of which involve

the imposition of the death penalty for differing sorts of

: A a al 3 ge homicides, and the third ©

0 reagulired to be filed in the three case

4

]

(2) Undersigned counsel is responsible for preparing and

‘iling the briefs on behalf of each petitioner. Co-counsel in

three briefs necessarily falls upon undersigned counsel.

(3) Considerable portions of undersigned counsel's time

since June 28, 1971 have been consumed by attention to other | capital cases in which this Court reversed death sentences on

Ls ra "( vy ga wn EE. ET. SET ~ pa i ~ i a June 28, whereln undersigned counsel tl

~ ~~ _ - )

represenced

and to the implications of the Court's actions of June 28 for

counsel is lead counsel in a habeas corpus proceeding pending

the death penalty for rape. Three separate briefs are therefore

the three cases have limited responsibilities, and the principal

work of research and drafting involved in the preparation of all

- i orn i

Lie Detlcloners,

additional capital cases pending in the lower courts. Undersigned

in

1 the United States District Court for the Middle District of

2) i 2s ma Te hi ‘a : :

co Florida on behalf of Florida's 80 condemned men, and is required

9 ’ ging ' ‘

to appear at a hearing set by the presiding judge in that case on

A.

Il July 30, 1971, for the purpose of considering the effect upon that]

proceeding of this Court's several June 28 actions.

7 (4) In all of these capital cases, undersigned counsel is an

8 uncompensated volunteer representing indigent condemned men. None

f his clients is able to retain other counsel; and co-counsel in

each case are also volunteers, each having only limited time

available for the cases.

]

1% (5) Problems in composing the record in each of the Aikens,

14 Furman and Jackson cases make it impossible for undersigned counsel

=

15 Loli Din lt a citar) GR a Sr A DO SL A Tye] 9c "

i =O 08 da a Tale ul NTE WP | Oy or Lose Yecoras Yerore Jit —y LU yp 19 / 1 e

(6) For all of the foregoing reasons, it will not be pos-

sare and file briefs in these three cases N

ES sible for counsel to pre

prior to September 2, 1971.

>) i . « ; : :

<0 (7) Counsel for the State of Georgia have authorized me

to say that the respondent in Nos. 69-5003 and 69-5030 has no

00

Co 6

objection to the extension requested. Counsel for the State of

23

California is presently unavailable; I shall endeavor to make

24

{ hn : NT : : a

o his position concerning this application known to the Clerk at

<0

.

the earliest possible time.

27 Ci —————h

<8 | (1) In Aikens (No. 68-5027), the copy of the record certified |

oc | to this Court by the Clerk of the California Supreme Court was

4 petitioner's copy; and only half of the volumes compr ising the

trial transcript were certified. This was discovered by in-

vestigation during the first week of July. Accordingly, on July 9;

we asked the Clerk of this Court to send us the complete record.

P

R

L

i

Pr

ed

32 (continued)

o

3 x (continued)

4 That was received on July 12. It was immediately collated with

3 the portions of the record which we had; and on July 13, we

O arranged to have the clerk of the California Supreme Court

a certify the missing volumes to this Court. The clerk's file

in the case is in three volumes, and the trial transcript runs

7 to twenty volumes. Co-counsel read it through for the purpose

of agreeing with counsel for the State of California concerning

8 the contents of the Appendix; agreement was reached on July 19

and 20; and the agreed statement was mailed to this Court on

9 July 21. A copy of the record was then mailed to undersigned

counsel.

11 (2) In Furman (No. 69-5003), the original record is still

in the Georgia Supreme Court. Co-counsel in Georgia inspected

it there, for the purpose of comparing it with the petitioner's

copy of the transcripts and other documents in the record. After

these comparisons had been made, a copy of the record was sent

14 to co-counsel in New York, arriving in two batches on July 9

and July 21, to be read for designation. That entire record is

15 now. in the mail from New York to undersigned counsel. However,

our examination of it to date discloses that there are two

16 documents bearing upon the petitioner's psychiatric state

which are not included in the record, and which we are now at-

tempting to have certified by the Clerk of the Superior Court of

Chatham County to the Georgia Supreme Court, thence to be certi-

fied to this Court.

20 (3) In Jackson (No. 69-5030), the Clerk of this Court wrote

to the Clerk of the Georgia Supreme Court asking that a certified

21 copy of the record be sent up after counsel had had a chance to

inspect it in Georgia. The Clerk of the Georgia Supreme Court

22 mailed it to this Court on July 14 without waiting for counsel

to inspect it; and we first saw it on July 21, when a law clerk SS" .

' . . - EY .

“0 dispatched by New York co-counsel inspected it in Washington.

wy At this time we have petitioner's copy of the trial transcript, bug

4 ’ - ar . 5 i

no copies of any file papers; and we have discovered that a

or psychiatric report which should be in the record is not ingluded

in the certified record that this Court has. We are presently |

26 tracing that report; and, in the meantime, copies of the other |

file papers have to be duplicated and mailed to undersigned

27 ll counsel.

28 i |

29

30

31

62

N

J

[9

ey

week extension of

September

respectfully request a three-

thin which they must file their

SUCRE ty

V4 \ aa SC

/ nig

\; / £ om { § go erg k L

Urges” * V { Fi’ Ran

{i \. > it F | a

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Counsel for Petitioners

1 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

bo

Ne

a

I certify that I i served the foregoing Application for

) Extension of Time for Filing Petitioners' Briefs upon counsel

for respondents, at the addresses indicated below, by this day

4 depositing in the mail, first-class air-mail postage prepaid,

: two copies to each of ahem

6

Honorable Evelle J. Younger

7 Attorney General

600 State Building

8 Los Angeles, California 90012

, Attention: Ronald George, Esq.

Deputy Attorney General

Honorable Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

132 State Judicial Building

40 Capitol Square

13 Atlanta, Georgia 30334

Attention: Dorothy Beasley, Esq.

14 Assistant Attorney General

15

; Anthony G. i Tordanm

18 Counsel for Petitioners

29

ry

J 6