Poss v. McLucas Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Poss v. McLucas Brief in Opposition, 1989. 17793644-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/948f63ae-7aa8-4e89-82bd-98019dd694ef/poss-v-mclucas-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

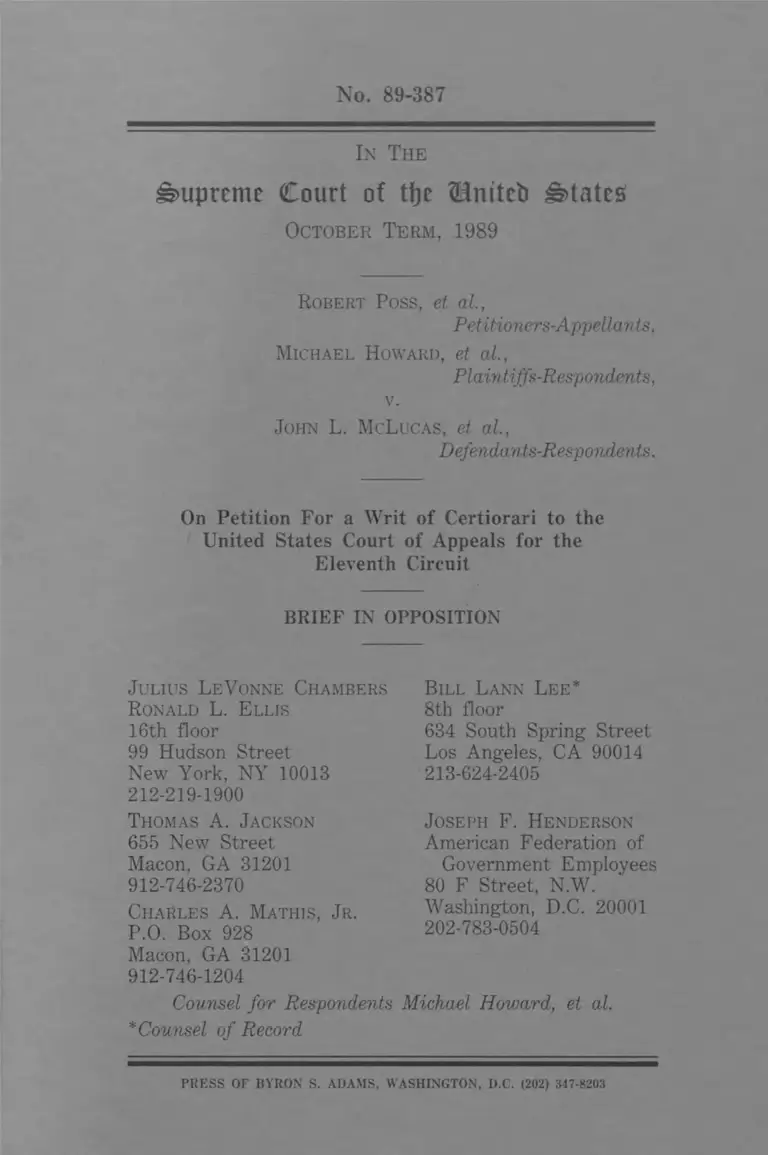

No. 89-387

In The

Supreme Court of t\)t ®nttcb states

October Term, 1989

Robert P oss, et a l,

Petitioners-Appellants,

Michael Howard, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

v.

J ohn L. McLucas, et al.,

Defendants-Responden ts.

On Petition For a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

J ulius Le Vonne Chambers

Ronald L. E llis

16th floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

212-219-1900

Thomas A. J ackson

655 New Street

Macon, GA 31201

912-746-2370

Charles A. Mathis, J r .

P.O. Box 928

Macon, GA 31201

912-746-1204

Bill Lann Le e *

8th floor

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213-624-2405

J oseph F. Henderson

American Federation of

Government Employees

80 F Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

202-783-0504

Counsel for Respondents Michael Howard, et al.

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether a consent decree that provides

promotions to victims of discrimination

violates Title VII or the Constitution in

a case in which the lower courts found

p e r v a s i v e o r i ma f a c i e r a c i a l

discrimination?

2. Whether two courts below correctly

found that the promotional provision was

narrowly tailored "to eliminate the

effects of past discrimination"?

i

LIST OF ALL PARTIES

Plaintiffs-Resoondents

Michael Howard, Henry Taylor, Jr., Oliver

Gilbert, Clifford Scott, Lewis T. Jones,

and Thomas W. Miller, on behalf of

themselves and all others similarly

situated, and the American Federation of

Government Employees and Irish Smith.

Defendants-Respondents

John L. McLucas, Secretary of the Air

Force; Major General W.R. Hayes, Commander

of Warner Robins Air Force Base and

Administrator of Warner Robins Air

Logistics Center; Robert Hampton, Chairman

of the United States Civil Service

Commission; Ludwig U. Andolsek,

Commissioner, United States Civil Service

Commission; Jayne B. Spain, Commissioner,

United States Civil Service Commission.

n

Petitioners-Intervenors

Larry W. Abney, Dennis Adams, David

Alford, Eddie C. Barfield, Katherine H.

Barkemeyer, William H. Barkemeyer, Joseph

N. Barlow, Howard Bell, Kathleen Bell,

Paul E. Benton, Wayne A. Bowden, Johnny D.

Bowen, Goldie Bright, Kenneth W. Brock,

Ronald K. Brown, Billy W. Bryant, Linda

Burnsed, Donald R. Buttorm, Kenneth R.

Camp, Barney Chandler, James B. Chappell,

Deanna Chase, Mary M. Clance, Robert L.

Clance, Dave Cochran, Bill Cody, Robert R.

Collins, Rusty Combs, Charles R. Cook,

Martha J. Cook, Donald C. Crosby, Eugene

A. Davis, Jim Davis, Kyle C. Dismuke,

David Dixon, Marvin T. Drew, John E. Dunn,

John A. Dunwoody, Joyce DuVernois, Donald

Easier, Dale Edge, Charles F. Evans, John

J. Evans, Billy S. Evatt, George Everette,

Roger W. Ferguson, Jay A. Fitzgerald,

Ronald A. Garrett, David C. Gilstrap,

in

Braxton B. Grantham III, Robert Gray,

Sheree W. Griffin, Rita Hall, Jimmy

Hamlin, Jackie R. Hammock, William H.

Hargrove, Albert L. Harrison, Charles C.

Harrison, Ferman Hatton, Michael G.

Haynes, Willie Heath, William F. Herring,

Jr., Dale A. Hoffman, Glynn Hooks, David

L. Horton, Cecil W. Hughes, Charlotte A.

Jackson, William C. Johnson, Jr., Danny L.

Joiner, Robert W. Kelly, Robert E.

Knodrak, Hugh Lewis, Billy Joe Little,

Calvin H. Lowery, Paula B. Malone, Richard

L- Marks, Leon Mathis, Randall R. Maxwell,

Stephen D. Mayo, William C. McLemore,

Clayton Mead, Michael C. Mead, Beverly R.

Meredith, Lelan S. Middleton, Donna W.

Mills, James A. Minor, Wayne E. Minor,

Robert W. Minter, Fred M. Mitchell,

Lenwood W. Moore, Roger Morrow, Cheri L.

Moss, Marion Ford Musselwhite, Richard L.

Nash, Tommy Parker, Tarrell T. Parkerson,

IV

Johnny Peacock, M. Louise Peterman,

Timothy Peters, Donald Peterman, Charles

W. Phillips, Earl J. Pilgrim, Charles

Porter, Robert T. Poss, Thomas Purvis,

Robert R. Reese, June Renfroe, Robert R.

Riggins, Jr., Gary T. Roberson, Rebecca L.

Scribner, Grady W. Selph, Robert Shiver,

Lillian N. Slappey, Richard J. Stafford,

Jimmy L. Stanley, James H. Stephens, Melba

Stokes, Ronald Strickland, Sue Sullivan,

Jimmie L. Thomas, Shirley A. Thomas,

Charles S. Vann, Frederick Veator, Richard

A. Wall, James A. Wallace, Herbert Weaver,

Herman B. West, Jr., Jim Wilcox, Larry H.

Wilkes, Charles E. Williams, Jr., Irene K.

Wilson, James E. Woodard, Jr., Ronnie

Norman Woods, David Wynne, Jimmie Yawn,

Hugh L. Yawn, and Martin A. Young.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............. i

LIST OF ALL PARTIES............. ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS............... vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............. vii

OPINIONS BELOW................... ix

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ........... 2

A. Prior Proceedings. . . . 2

B . FACTS..................... 7

1. Record of Discrimi

nation ........... 7

2. The Promotional

Provision........ 14

REASONS TO DENY THE WRIT 20

I. The Courts Below Correctly

Applied The Law Of This Court

In Upholding A Consent Decree

That Provides Relief To Specific

Victims Of Discrimination Based

On Showing Of Prima Facie

Discrimination............... 20

II. The Lower Courts Correctly

Decided That The Promotional

Provision Was Narrowly Tailored

"to Eliminate the Effects of

Pact Discrimination.". . . . 30

CONCLUSION....................... 34

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

gage

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 ( 1 9 7 5 ) ........ 23

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City,

470 U.S. 564 (1985)........ 33

Association Against Discrimination

in Employment, Inc., v. City

of Bridgeport, 479 F.Supp. 101

(D. Conn. 1979), aff'd 647

F.2d 256 (2d Cir. 1981), cert.

denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982). . 26

Blau v. Lehman, 368 U.S. 403 (1962) 32

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977)......................... 10

Domingo v. New England Fish Co.,

727 F.2d 1429 (9th Cir. 1984) 26

Firefighters v. Stotts, 467 U.S.

561 (1984)............ 21

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976)........ 22, 25

Howard v. McLucas, 671 F. Supp. 756

(M.D.Ga. 1987) .......... passim

Howard v. McLucas, 597 F. Supp. 1512(M.D.Ga. 1984). .

Howard v. McLucas, 597 F. Supp. 1501(M.D.Ga. 1984). .

Vll

5Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956

(11th Cir. 1986)..........

International Brotherhood of

Temasters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977). . . 20, 25, 26

Johnson v. Transportation Agency,

480 U.S. 616 (1987)... 28, 29, 31

Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC

478 U.S. 421 (1986)... 20, 23, 27

Local No. 93, InternationalAssociation of Firefighters

v. City of Cleveland,

478 U.S. 501 (1988)........... 21

Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145 (1965)........... 23

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 439 U.S. 1115

(1979)....................... 25

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

109 S.Ct. 1775 ............... 24

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249

(D.C. Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

471 U.S. 1115 (1985) . . . . 25, 26

Stewart v. General Motors Corp.,

542 F.2d 445 (7th Cir. 1976)

cert, denied, 433 U.S. 919

(1977)....................... 26

United States v. Johnston,

268 U.S. 220 (1925)........... 33

v i i i

28, 29United States v. Paradise,

480 U.S. 149 (1987). . .

United Steelworkers v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979)........ 22, 28

University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978).......... 22

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,

109 S. Ct. 2115

(1989)......................... 8

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) 14, 28, 29, 31

IX

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit is reported at

871 F. 2d 1000 (1989) and is reprinted in

Appendix A of the Petition. The opinion

of the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Georgia of

September 30, 1987, as supplemented

October 5, 1987, is reported at 671 F.

Supp. 756 (1987). Petitioners reprinted

the incomplete opinion in their Appendix

B. Respondents will refer to the complete

published district court opinion instead

of Appendix B.

x

No. 89-387

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term 1989

ROBERT POSS, et al.,Petitioners-Appellants

MICHAEL HOWARD, et al.,Plaintiffs-Respondents,

v.

JOHN L. McLUCAS, et al.,Defendants-Respondents

On Petition For A Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Respondents Michael Howard, et al.,

plaintiffs below, request that the

petition for writ of certiorari filed by

intervenors Robert Poss, et al., be

denied.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Prior Proceedings

This Title VII action was originally

filed on October 31, 1975 by black

civilian employees of the Warner Robins

Air Logistics Center ("Warner Robins")

against defendant Secretary of the Air

Force to challenge the denial of

promotions to black employees. With

approximately 15,000 civilian employees,

Warner Robins is one of the largest

employers in the State of Georgia. In

1976 the lawsuit was certified as a class

action on behalf of approximately 3200

black employees.

After numerous pre-trial proceedings

and extensive discovery, the parties

submitted a proposed consent decree. A

fairness hearing was held pursuant to

Rule 2 3 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure in August 1984. The district

2

court received extensive evidence of

discrimination, and found that "plaintiffs

have made out a orima facie case of

employment discrimination through the use

of s t a t i s t i c a l e v i d e n c e of

disproportionate racial impact," Howard v.

McLucas. 671 F. Supp. 756, 760 (M.D. Ga.

1987), by " p r e s e n t [ing] numerous

statistical studies of work force, grade

levels, occupational segregation,

promotions, training, supervisory

appraisals, test scores, and awards that

demonstrate pervasive patterns of

discrimination in the internal promotional

system at Warner Robins." id. at 7 66.

The district court also received evidence

of the nature and effect of the

promotional relief provided by the consent

decree. Id. at 761-68.

Robert Poss and 136 other white

employees objected and were allowed to

3

participate in the fairness hearing as

objectors. See Howard v. McLucas, 597 F.

Supp. 1512, 1514 (M.D. Ga. 1984). Their

counsel argued, presented evidence and

examined witnesses. The court, however,

denied their motion to participate

formally as intervenors with the right to

veto the settlement. Howard v. McLucas.

597 F. Supp. 1501 (M.D. Ga. 1984).

Several class members also objected.

Rejecting the objections of both black and

white employees, the district court

approved the consent decree.

The consent decree states that the

promotion of 240 class members to every

other available vacancy in specified jobs

settled the claims of class members who

alleged that they were victims of

discrimination. See R. 256 at 6.

Members of the class were selected for

promotion through a victim identification

4

procedure, which the district court found

identified those most likely to have been

denied promotions on discriminatory

grounds. The consent decree also provided

for a $3.75 million class backpay fund and

other injunctive relief.

In 1986, the Eleventh Circuit

reversed the district court's denial of

the white employees' motion to intervene.

The court of appeals authorized

intervention of Poss and the other white

employees, but expressly limited their

participation to challenging the

promotional provision. Howard v.

McLucas, 782 F.2d 956, 960-61 (11th Cir.

1986). The court denied authorization to

intervenors to continue to challenge any

other remedial provisions or to contest

the district court's underlying findings

of discrimination.

After considering the intervenors'

5

and parties7 submissions on remand, the

district court rejected intervenors'

objections, which are reiterated in their

petition. The court approved the decree

"because it is based upon a predicate

finding of discrimination by defendants

and is victim specific." 671 F. Supp. at

767-68. The court also found that, to

the extent the relief is not victim

specific, it was narrowly tailored to

eliminate the discrimination found. Id. at

768. The court of appeals affirmed on the

same grounds. Pet. 10a-20a. Motions for

a stay were denied by the Eleventh Circuit

and this Court. En banc review was denied

by the Eleventh Circuit. Pet. D.

Although petitioners fail to

acknowledge the victim-specific nature of

the promotional relief, two courts below

upheld the decree precisely because it is

victim specific. E .g.. 671 F. Supp. at

6

766 ('• [T]he court is fully persuaded that

only identified victims of discrimination

will benefit from the promotional

relief."). Petitioners also fail to

acknowledge that intervenors' objections

that the promotional procedure was not

n a r r o w l y t a i l o r e d to eliminate

discrimination were rejected by both

courts below.1

10n remand, intervenors were given a

plenary opportunity to challenge the

promotional provision. They failed to

show that "any of the plaintiffs were not

discriminated against." Pet 19a; see 671

F. Supp. at 764. None of the intervenors,

moreover, presented any evidence that he

or she had been injured in any way by

operation of the promotional provision.

Pet. 2a. The district court found that

the intervenors presented no evidence of

injury, and that 43 of the 137 intervenors

had been promoted and another 56 were

ineligible for promotion. 671 F. Supp. at

767 n. 4. The court of appeals found

that, none presented evidence of any delay

in receiving promotions. Pet. 9a.

Notwithstanding intervenors' "tenuous"

position to contest the consent decree,

the courts below addressed the merits

because "some delay may have occurred."

Id.

7

B. FACTS

1. Record of Discrimination

The petition suggests that the

promotional provision was based on a

single statistic showing a disparity.

This is incorrect. The lower courts found

that a orima facie case had been proved

with extensive statistical evidence of

pervasive discrimination. Pet. 4a-5a, 671

F. Supp. at 760-61, 766.

Warner Robins for many years has

filled upper level jobs by promoting

qualified employees in lower level jobs

through an internal promotion system on

the basis of seniority, written

examinations, supervisory appraisals,

training, and awards. 597 F. Supp at

1508-09.2 Nevertheless, the record shows

2This case, therefore, is unlike

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio. 109 S.

Ct. 2115 (1989), in which higher level

jobs were filled through outside

recruitment rather than internal promotion.

8

that blacks "were concentrated in low

level jobs and certain occupations." Pet.

4a, quoting 597 F. Supp at 1513. In 1973,

when plaintiffs' administrative charges

were filed, fully three quarters of black

WG employees were in the lowest job

levels, compared to less than a third of

the white WG employees. See Pet. 4a, 671

F. Supp. at 760. Blacks were concentrated

in menial occupations with little

advancement potential. Although only 15%

of the Warner Robins workforce, blacks

constituted 86% of all janitors, 81% of

all laborers, 76% of all packers, 76% of

all motor vehicle operators, 71% of all

woodcrafters and 67% of all parts and

equipment operators. See Pet. 4a.

Statistics also "demonstrated that

black employees were promoted ... in

proportions less than their representation

in the workforce or in lower grades."

9

Pet. 4a, 671 F. Supp. at 760, quoting 597

F. Supp at 1510. Plaintiffs compiled two

statistical analyses of promotions, which

were introduced by stipulation. See 597

F. Supp. at 1508 n. 1. The first showed

that significant statistical disparities

in promotion rates out of WG grade groups

and GS grades 1-4, and that blacks lost

553 jobs from 1971-78.3 The second

analysis, more conservative because it

3

Grade GrouD

Number

of Standard

Deviations

Expected

Promotions

Lost to Blacks

WG 1-4 6.01 67.98WG 5-8 16.03 362.00WG 9-12 4.80 50.06GS 1-4 3.56 72.67

See Pet. 4a, 671 F. Supp. at 760, 597 F

Supp. at 1610. Fluctuations of more than

two or three standard deviations undercut

the hypothesis that selections for

promotions were being made randomly with

respect to race. See Castaneda v.

Partida. 430 U.S. 482, 496 n. 17 (1977).

10

controlled for occupational series,4

showed statistically significant

disparities in WG categories, but no

significant disparities in GS jobs. The

conservative analysis showed blacks lost

234 jobs.5

Defendant Warner Robins also prepared

an analysis of promotion statistics for

trial, which plaintiffs summarized. The

g o v e r n m e n t ' s s u b m i s s i o n s h o w e d

statistically significant disparities out

of WG jobs and concluded that blacks lost

4The record, however, indicates that

employees in different series were

qualified to be promoted to the same job.

See R. 275, Tab E (government exhibit

showing large pools of qualified employees

for particular positions).

Number Expected

5 of Standard Promotions

Grade Group Deviations Lost to Blacks

WG 1-4 3

WG 5-8 8

WG 9-12 3

53 36.68

19 162.84

75 34.74

See Pet. 4a, 671 F. Supp. at 761.

11

328 positions.6

All the selection criteria used by

Warner Robins, with the exception of

seniority, had significant adverse impact

on black employees. Id. See R. 285 at

40-41; R. 156, 28-37; R. 269, §§3d-h & k;

R.268, Exhibit 1, 47-73, 100-07. For

instance, while fluctuations of more than

two or three standard deviations are

sufficient to undercut the hypothesis that

a selection device has a racially random

effect, the passing scores of black

employees on written examinations varied

by as much as 50 standard deviations from

those of'white employees. R. 268, Exhibit

1 at 100; see id. at 100-07. Government

Number Expected

6 of Standard Promotions

Grade Group Deviations Lost to Blacks

WG 1-4 4.60

WG 5-8 9.50

WG 9-12 4.29

70.98

209.72

46.53

R. 268, Exhibit 1, 85.

12

documents admitted the adverse impact.

Warner Robins' EEO affirmative action

plans stated that disparities in training

were a "problem": For example,

"[m]inorities received a disproportionate

share of training in CY 1973 — 7% of the

total compared to their 15.2% population."

R. 156, 30, 3a (admission) . The 1976

affirmative action plan stated that

"[l]ower appraisals for . . . minorities

r e s u l t in r e d u c e d p r o m o t i o n a l

opportunities." See id. at 32, 3a

(admission). EEO documents show

consistent racial disparities in awards

given to employees, which "no doubt

reflects in the promotion figures where

awards are ranking factors." See id. at,

38, 4a (admission).

The finding by the lower courts of

unrebutted evidence showing prima facie

discrimination in denial of promotions was

13

amply supported. That unrebutted evidence

was thus "sufficient evidence to justify

the conclusion that there has been prior

discrimination." Wygant v. Jackson— Board

of Education. 476 U.S. 267, 277 (1986).7

2. The Promotional Provision

The district court found that class

members identified for the 240 promotions

were likely to have been eligible for the

same promotions during the period when the

discriminatory policies were in force,

and, therefore, were "likely victim[s] of

discrimination entitled to relief." 671

F. Supp. at 764, see id. at 763. "A more

specific way of identifying these actual

7Intervenors attach great weight to

the fact that Warner Robins did not

concede liability in the consent decree.

Interveners ignore, however, that Warner

Robins stipulated that the statistical

disparities cited above, that undergird

the prima facie discrimination findings,

were true and correct. See 671 F. Supp.

at 766 n.l; 597 F. Supp. at 1511 n. 1,

1513; R. 285 at 8-11, 40-41.

14

victims does not exist in this case." Id.

at 763.

Because of Warner Robins' promotional

system and record-keeping procedures, it

was impossible to identify all employees

who were actually qualified for promotion

to jobs lost to blacks in the 1971-79

period, or even to reconstruct their

qualifications at the time.8 The

supervisory appraisals and test scores of

specific employees in the period are

unavailable or incomplete. Pet. 3a-4a.

It was also impossible to definitively

rank the best qualified employees because

all the then-existing criteria used for

determining qualification, except

8 All employees were considered for

promotion through a computerized ranking

process in which qualifying criteria of

employees were automatically assessed as

vacancies came up. 597 F. Supp. at 1509.

Warner Robins does not use the more usual

announcement or posting system in which

employees apply for promotions. 597 F.

Supp. at 1508.

15

s e n i o r i t y , w e r e s h o w n to be

discriminatory.

The parties used plaintiffs'

conservative promotional analysis to

identify the number of promotions lost to

blacks and the specific jobs most likely

to have been lost to blacks.9 The

parties then used the contemporaneous and

only available computerized ranking of

eligible class members present in the

workforce during the relevant period in

order to identify specific victims.

Seniority and supervisory appraisal scores

were used, but seniority, the only non

9 671 F. supp. at 762 (The 240

positions "represent, to the best extent

possible, the most likely jobs lost to

blacks from 1970 through 1979 as a result

of the discrimination at Warner Robins.");

597 F. Supp. at 1513-14 ("Plaintiffs'

computer-based promotional analysis for

occupational series was actual evidence

that approximately 240 promotions were

lost to black WG employees . . . [T]he

positions to be filled by blacks should

have been filled by blacks years ago.").

16

discriminatory criteria, was given

greatest weight.

The district court, therefore, had an

ample basis to find that "the victim

identification process . . . [was] a

reliable and narrowly tailored process

designed to assure that only victims of

discrimination be afforded relief." 671

F. Supp. at 764 (emphasis added).

The district court heard and rejected

intervenors' objections to the scope of

the promotional provision. The court

found that "to the extent the relief is

not victim specific, it is still lawful

since it is necessary to provide full

relief to class members, it is flexible,

waivable, and of limited duration; the

number of positions offered is limited to

the specific number of jobs statistically

proven to have been lost to class members;

and, finally, it does not unnecessarily

17

trammel the rights of third parties or

create an absolute bar to their

advancement since the impact of the relief

is relatively diffuse in nature and many

promotional opportunities continue to

exist for these third parties." 671 F.

Supp. at 768.

The court expressly found that there

was no "less intrusive approach that might

provide full relief to class members

within a reasonable period of time." Id.

at 767. The court, therefore, had

substantial basis to conclude that the

decree was narrowly tailored to eliminate

prior discrimination.

18

REASONS TO DENY THE WRIT

I

The Courts Below Correctly Applied

The Law Of This Court In Upholding A

Consent Decree That Provides Relief

To Specific Victims Of Discrimina

tion Based On A Showing Of Pervasive

Prima Facie Discrimination.

Petitioner intervenors assert that

this case presents the important federal

question whether an affirmative action

set-aside can be justified by a mere

underutilization of blacks. Pet. 11.

This contention fails for two reasons:

Petitioners initially claim that the only

factual predicate for the promotional

measure is "a statistical under

utilization of blacks." The courts below

found pervasive prima facie discrimination

on the basis of a substantial record.

Such a statistical showing "proved a prima

facie case of systematic and purposeful

19

International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324, 342 (1977). Second,

petitioners claim that the promotional

provision in question is an affirmative

action program for employees who were not

victims of discrimination. As the two

lower courts correctly found, however, the

promotions are specific relief for 240

victims of discrimination. Moreover,

" [ i ] ntervenors have failed to show that

any of these class members were not

victims of defendants' discrimination."

671 F. Supp. at 764.

The instant case simply does not

concern the permissible scope of

affirmative action. The defining

characteristic of affirmative action plans

is that they are not confined to providing

r e l i e f to a c t u a l v i c t i m s of

discrimination. See Local 28. Sheet

employment discrimination,"

20

Metal Workers v. EEOC. 478 U.S. 421, 474

(1986) ("The purpose of affirmative action

is not to make identified victims whole,

but rather to dismantle prior patterns of

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n and to p r e v e n t

discrimination in the future . . . .

[B] enef iciaries need not show that they

w e r e t h e m s e l v e s v i c t i m s of

discrimination") ; Local No. 93,

International Association of Firefighters

v. City of Cleveland. 478 U.S. 501, 515

(1986) ("courts may, in appropriate cases,

provide relief under Title VII that

benefits individuals who were not the

actual victims of a defendant's

discriminatory practices"); Firefighters

v. Stotts. 467 U.S. 561, 579 (1984)

(observing that the plan under review was

supported by "no finding that any of the

blacks protected from layoff had been a

victim of discrimination").

21

As the Court noted in Regents of

University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265, 301 (1978), "some burdens on

other employees" and "various types of

racial preferences" were tolerated in

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.. 424

U.S. 747 (1976), and other employment

discrimination cases. Such victim-

specific provisions, however, were

distinguishable from similar measures in

affirmative action programs because they

were "held necessary '"to make [the

victims] whole for injuries suffered on

a c c o u n t of u n l a w f u l em ployment

discrimination"'" and were "remedies for

constitutional or statutory violations

resulting in identified, race-based

injuries to individuals held entitled to

the preference." Bakke. 438 U.S. at 301

(quotations omitted).

This Court long ago held that a

22

central purpose of Title VII is "to make

persons whole for injuries suffered on

a c c o u n t of u n l a w f u l employment

discrimination." Albermarle Paper Co. v.

Moodv. 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975); see

Local 28. Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 478

U.S. at 471 (individual "make whole"

relief is not the only kind of remedy

available under Title VII). The "make

whole" purpose of Title VII is consistent

with the historic purpose of the Civil

Rights Acts to secure complete justice for

victims of racial discrimination. "[T]he

court has not merely the power but the

duty to render a decree which will so far

as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future." Louisiana

v. United States. 380 U.S. 145, 154

(1965) .

Relief to individual victims of

23

discrimination is justified on the record.

A finding of pervasive, classwide

discrimination such as the district court

made in this case is an appropriate basis

for relief to individual class members.

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. 109 S.Ct.

1775, 1799 (1989) (O'Connor, J.,

concurring) ("Because the class has . . .

demonstrated that, as a rule, illegitimate

factors were considered in the employer's

decisions, the burden shifts to the

employer 'to demonstrate that the

individual applicant was denied an

employment opportunity for legitimate

reasons.'") (citations omitted). The law

is settled that "[b]y 'demonstrating the

existence of a discriminatory

pattern and practice' the plaintiffs

ha[ve] made out a prima facie case of

discrimination against the individual

class members.'" Teamsters. 431 U.S. at

24

Bowman3 5 9 , q u o t i n g F r a n k s v .

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 772

(1976). "[P]roof of a discriminatory

pattern and practice creates a rebuttable

presumption in favor of individual

relief." Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 359 n.

45.

Courts, moreover, have recognized

that the process of recreating the past,

for example, in order to identify victims

of discrimination, "will necessarily

involve a degree of approximation and

imprecision." Teamsters. 431 U.S. at 372.

See Seaar v. Smith. 738 F.2d 1249, 1289 &

n.36, 1290 (D.C. Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

471 U.S. 1115 (1985); Pettwav v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co.. 494 F.2d 211, 260 (5th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied. 439 U.S. 1115

(1979). While individualized hearings are

"usually" required, Teamsters. 431 U.S. at

361, they are not mandatory "when the

25

class size or the ambiguity of promotion

or hiring practices or the multiple

effects of discriminatory practices or the

illegal practices continued over a

extended period of time calls forth [a]

quagmire of hypothetical judgment [s] .11

Pettwav. 494 F.2d at 261. See Domingo v.

New England Fish Co. , 727 F.2d 1429, 1444

(9th Cir. 1984); Segar. 738 F.2d at 1290;

Stewart v. General Motors Corp. , 542 F.2d

445, 452-53 (7th Cir. 1976), cert, denied.

433 U.S. 919 (1977); Association Against

Discrimination in Employment. Inc., v.

City of Bridgeport. 479 F.Supp. 101, 115

(D. Conn. 1979), aff'd. 647 F.2d 256 (2d

Cir. 1981) , cert, denied. 455 U.S. 988

(1982). In the instant case, the

challenged remedy employed the best method

possible under the circumstances to

identify victims of pervasive promotional

discrimination. See 597 F. Supp. at 1504

26

("The present parties have labored to

reconstruct the record of thousands of

personnel actions and have identified as

best as possible the actual impact of past

discrimination").

A s s u m i n g a r g u e n d o that the

promotional provision is not a victim-

specific remedy but an affirmative action

remedy for nondiscriminatees, the measure

is, nevertheless, appropriate. The lower

courts ' findings of orima facie

discrimination are based on separate

showings of promotional disparities and

the adverse impact of a broad range of

promotional criteria, buttressed by

admissions in Warner Robins' affirmative

action plans. This record of "persistent

or egregious" discrimnation or "lingering

effects of pervasive discrimination,"

Local 28. supra, 478 U.S. at 476, as the

Eleventh Circuit properly held, showed

27

"that the government had a sufficient

basis for concluding that remedial action

was necessary." Pet. 13a. In so finding,

both lower courts specifically measured

the promotional provision against the

legal principles set forth in the Court's

recent affirmative action decisions under

Title VII and the Constitution. E.g. ,

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149

(1987); Johnson v. Transportation Agency.

480 U.S. 616 (1987); Local 28. 478 U.S.

421; Wvgant v. Jackson Board of Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) . The lower courts

found not only a "manifest imbalance" in

"traditionally segregated job categories",

Johnson. 480 U.S. at 631; United Steel

workers of America v. Weber. 443 U.S. 193,

197 (1979) , but "sufficient evidence to

justify the conclusion that there has

been prior discrimination." Wvgant. 476

U.S. at 277. See Paradise. 480 U.S. at

28

167 ("The government unquestionably has a

compelling interest in remedying past and

present discrimination"). Wygant, 476

U.S. at 286 (O'Connor, J., concurring)

("The Court is in agreement that,

whatever the formulation employed,

remedying past or present racial

discrimination by a [governmental] actor

is a sufficiently weighty [governmental]

interest to warrant the remedial use of a

carefully constructed affirmative action

program". The record in this case,

therefore, justifies race conscious

relief.

The particular form of race conscious

relief, the set aside of 240 promotions,

is fully commensurate with the orima facie

case, and was found to be the only measure

under the circumstances that "would

provide the full relief necessary to

remove promptly the remaining vestiges of

29

Pet.discrimination at Warner Robins".

15a; 671 F. Supp. at 7 67. Review on

Certiorari, therefore, is inappropriate.

30

II

The Lower Courts Correctly

Decided That The Promotional

Provision Was Narrowly Tailored

"to Eliminate the Effects of

Past Discrimination."

Petitioners assert that the Eleventh

Circuit failed to consider race neutral

alternatives and that the promotional

provision was not narrowly tailored. With

respect to the first assertion,

petitioners had an opportunity to present

alternatives both at the Rule 23 fairness

hearing and subsequently on remand from

the Eleventh Circuit. On neither occasion

did they present any race-neutral

p r o p o s a l s . 10 That omission is

understandable: Warner Robins, as

petitioners point out, has had an

affirmative action program, pursuant to

10See Johnson v Transportation

Aaencv. 480 U.S. at 628; Wyqant v.

Jackson Bd. of Education. 476 U.S. 277-78

(burden of proof on intervenors to show

unconstitutional violation of Title VII).

31

which the kinds of race-neutral measures

petitioners now propose were employed.

See 41 CFR 60-2.20-2.26. Warner Robins'

affirmative action reports admitted that,

notwithstanding these efforts, patterns of

orima facie discrimination occurred. The

parties, therefore, were correct in

assuming that race-neutral measures of the

kind petitioners espouse now would have

been ineffective.

With respect to narrow tailoring, the

lower courts gave petitioners a full

opportunity to make their case and

rejected their factual contentions that

the promotional provision could have been

more narrowly drawn. Pet. 15a-19a; 671

F. Supp. at 766-67. These twice-rejected

contentions are neither meritorious nor

appropriate for certiorari. See. Blau v.

Lehman. 368 U.S. 403, 411 (1962). They

merely seek to enlist the Court in

32

reviewing evidence and discussing specific

facts. United States v, Johnston. 268

U.S. 220, 227 (1925); see Anderson v City

of Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 564, 574 (1985)

("Where there are two permissible views of

the evidence, the factfinder's choice

between them cannot be clearly

erroneous").

The courts below properly found that

the promotional relief was necessary and

that other proposed remedial alternatives

were not feasible. Pet. 16a; 671 F. Supp.

at 767. "The flexibility and short

duration of the promotional relief cannot

seriously be called into question." Pet.

17a, 671 F. Supp at 766-67. "The 240

special promotions do not represent or

achieve any aggregate proportionality" or

numerical goal. Pet. 17a. The impact of

the provision is "relatively diffuse" and

spread throughout the workforce. Pet. 18a,

33

671 F. Supp. at 766-67. They constitute

only 4.3% of the total Warner Robins

promotions. Pet. 7a; 671 F. Supp. at 767.

The best method of determining the actual

victims of discrimination was utilized.

Pet. 19a; 671 F. Supp. at 766-67. Two

courts below made extensive findings that

"[w]hile the identification process is not

flawless, it is, in the court's best

judgment, a reasonable and fair identi

fication procedure designed to choose the

most likely victims of dis-crimination,"

in light of the available documentary

sources and peculiarities of the Warner

Robins promotional process. 671 F. Supp.

at 765. Petitioners' contentions,

including the claim that the government

"willfully destroyed records during the

pending of this litigation", Pet. 36a,

were properly rejected as incorrect and

frivolous. 671 F. Supp. at 763-65.

34

CONCLUSION

The petition for writ to the Eleventh

Circuit should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Ronald L. Ellis

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

212- 219-1300

Bill Lann Lee

8th Floor

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213- 624-2405

Thomas A. Jackson

655 New Street

Macon, GA 31201

912-746-2370

Charles A. Mathis, Jr.

P. 0. Box 928

Macon, GA 31201

912-746-1204

Joseph F. Henderson

American Federation of

Government Employees

80 F Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20001

202-783-0504

Counsel for Respondents

35