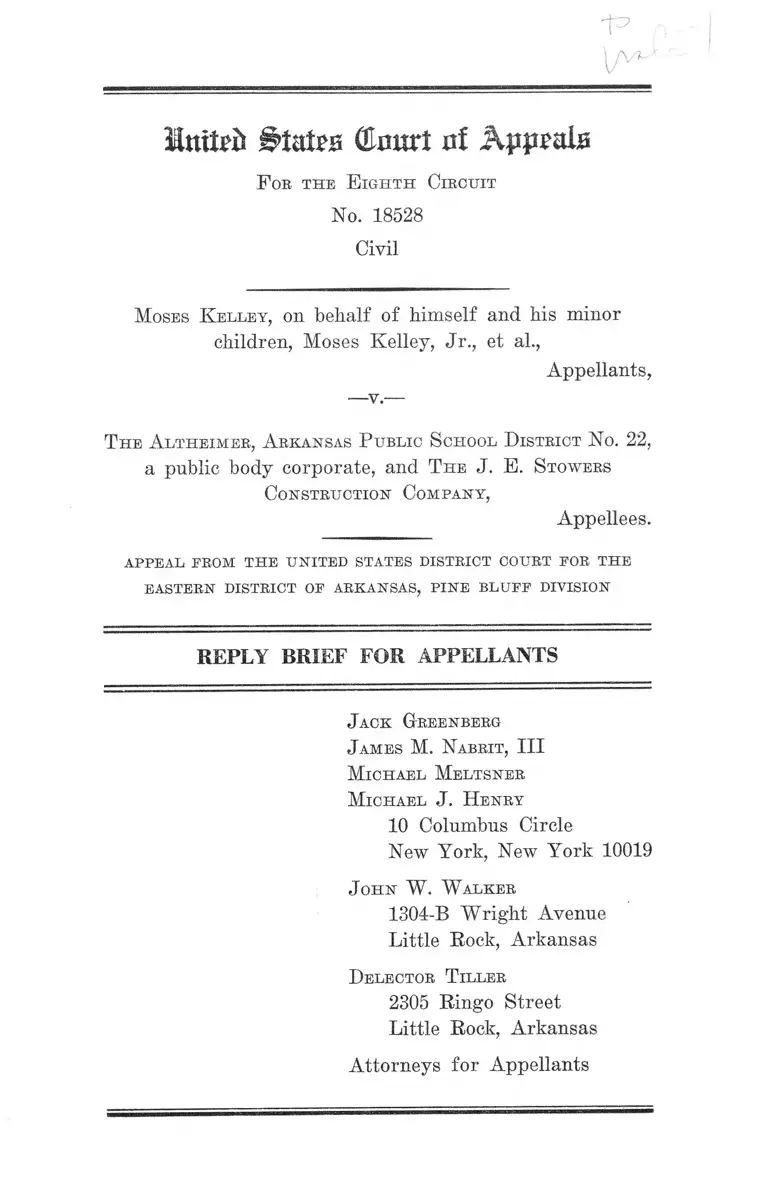

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Reply Brief for Appellants, 1966. d07b93c2-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/94b0e24c-175f-449a-a26b-4e454898232a/kelley-v-the-altheimer-arkansas-public-school-district-no-22-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

Imta* &mxl ni App?sta

F or t h e E ig h t h C ir c u it

No. 18528

Civil

M oses K ell e y , o il behalf of himself and his minor

children, Moses Kelley, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

T h e A l t h e im e r , A rkansas P ublic S chool D istr ic t N o. 22,

a public body corporate, and T h e J. E. S tow ers

C o n stru ctio n Co m pa n y ,

Appellees.

A PPEA L PRO M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IST R IC T COU RT EOR T H E

EA STER N D IST R IC T OP A RK ANSAS, P IN E B L U F F D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J am es M . N abrit , III

M ic h a e l M eltsn er

M ic h a e l J . H en r y

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

D elector T il l e r

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

Intttft Bu Ub GJmtrt of

F ob t h e E ig h t h C ir c h it

No. 18528

Civil

M oses K elley , on behalf of himself and his minor

children, Moses Kelley, Jr., et ah,

Appellants,

T h e A l t h e im e b , A rkansas P u blic S chool D istr ic t N o. 22,

a public body corporate, and T h e J. E. S tow ers

Co n stru ctio n C o m pa n y ,

Appellees.

A PPEA L PROM T H E U N IT E D STA TES D ISTR IC T COU RT FO R T H E

EA ST E R N D ISTR IC T OP A RK A N SA S, P IN E B L U P P D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Since the time of the filing of the Brief of Appellants,

two landmark school desegregation cases have been decided

by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth

Circuit—Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Robert L. Dowell, et al., No. 8523, January 23,

1967—and by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit—United States of America and Linda Stout,

et al. v. Jefferson County (Ala.) Board of Education, et al.,

Nos. 23345, etc., December 29, 1966, Petition For Rehearing

En Banc granted; oral argument denied, February 9, 1967.

2

Both of these cases undisputedly stand for the proposi

tion that a school board which has operated a legally

compelled segregated school system is under a duty to re

organize that school system in such a way as to maximize

the degree of desegregation. Furthermore, both cases em

phasize that in assessing the Constitutional adequacy of

a plan of desegregation results are what count; a “plan”

which promotes or gives rise to continued segregation or

token desegregation is not good faith compliance with a

board’s constitutional duty under Brown v. Board of Edu

cation. Both cases are clear in pointing out that the lan

guage in Northern school cases, where there was no legal

segregation, about there being no duty to remedy “racial

imbalance” is clearly inapplicable to a Southern school

system which brought about segregation and “inherent

inequality” of schools by state action.1

An example of the scope of the duty of a school board

to maximize the degree of desegregation in its system

where it had previously sought to maximize segregation is

the Oklahoma City case. There the Court required that

two pairs of attendance districts be consolidated in order

to increase desegregation and guard against expected

future segregation caused by gradual expansion of a

Negro residential area. The relief granted and the facts

which gave rise to it are conceptually indistinguishable

from the situation which prevails in the Altheimer district.

As the Tenth Circuit described the facts:

1 Appellees err in their contention that these decisions are out of step

with Supreme Court jurisprudence. As indicated in our original brief,

Supreme Court decisions in the school desegregation area support the

very extensive duty to maximize desegregation found by courts in the

Oklahoma City and Jefferson County cases.

“The first of those procedures requires the consolida

tion of Harding and Northeast districts and Classen and

Central districts. Each of the old districts now maintains

a school including the seventh through the twelfth grades.

Upon consolidation, each of the two new districts would

maintain two schools in the existing facilities, one for

the seventh through the ninth grades and the other for the

tenth through the twelfth grades. The combination of

Harding and Northeast would produce a racial composition

of 91% white and 9% non-white; the combination of

Classen and Central would produce a racial composition

of 85% white and 15% non-white. The present racial

compositions in the four schools are : Harding 100% white,

Northeast 78% white, Classen 100% white and Central

69% white. Under the new plan, the amount of traveling

required by pupils in the merged districts would be no

greater than some pupils in other parts of the system

are now required to travel and no busing problem arises

from the merger. The court recognized this fact and

expressly eliminated the necessity for busing in its plan.

It is obvious this part of the plan would result in a broader

attendance base and in a better racial distribution of the

pupils.” 2

2 Tlie district court in Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244

F. Supp. 971, 977 (W.D. Okla 1965) stated:

The recommendation that the zone lines of the integrated Northeast

and all-white Harding High Schools and the integrated Central and

all-white Classen High Schools be combined provides a further method

of overcoming the results of residential segregation which, because of

the Board’s inaction, has resulted in the maintenance of schools based

on race. The combining of the zones as suggested in the Report and

testimony (with the Board to determine which school in each set is to

be used for grades 7-9 and which school is to be used for grades

10-12) is reasonable and educationally sound. I t will require pupils

to travel no greater distance than many are presently traveling to

reach schools at the secondary level.

4

It is to be noted that the Oklahoma City school system

had a substantially greater degree of desegregation (20%)

at the time of the entry of the consolidation order, than

the Altheimer system, but this was still held to be inade

quate because the system had not been reorganized in such

a way as to maximize the degree of desegregation. The

Fifth Circuit decision in Jefferson County articulates iden

tical principles. For example, school boards are specifically

ordered to “locate any new school and substantially expand

any existing schools with the objective of eradicating

the vestiges of the dual system and of eliminating the

effects of segregation.”

Here in Altheimer we have a very simple school system

in which there are three clear-cut choices of re-organiza

tion: (1) Altheimer site for higher grades and Martin

site for elementary grades; (2) Martin site for higher

grades and Altheimer site for elementary grades; (3) com

pletely dual schools at both sites. Because there are only

two school sites in the district choice (1) or (2) results in

disestablishment of the segregated system and, therefore,

complete desegregation. The school board has chosen the

third alternative, which is the one under which only token

desegregation will take place. Although it had the oppor

tunity to do so, the Board failed to suggest any educational

explanation or interest for maintaining duplicate schools

six blocks from each other in the face of evidence that

such a system is educationally inefficient, financially waste

ful, and minimizes desegregation (see e.g. B. 55, 57, 61-63).

We do not believe that the Board’s affirmative duty of good

faith compliance with Brown v. Board of Education is met

by such conduct especially where, as here, the planning of

replacement construction was part and parcel of adminis

tration of a segregated system (see B. 55, 109, 110, 182).

5

A final point. The Board argues that “if a sufficient

number of Negro students chose to attend the Altheimer

school complex to overcrowd that facility, the students in

the overcrowded classes or grades would all be assigned,

on the basis of the proximity to their homes to the two

schools involved and this might well result in the assign

ment of some white students to the Martin Schools”

(Brief of Appellees, pp. 24, 25). This argument makes

sense in a school system with a number of different school

sites scattered through a community. It falls of its own

weight in the unique situation prevailing in Altheimer

where only about 200 of 1400 pupils live within the city

of Altheimer (R. 179), where %rds of the students arrive

at schools by bus (R. 28-29) and the schools are only six

blocks apart (R. 179, 228).

As almost all of the students in the district live at a

great distance from the schools, and the schools are so

close together, it is impossible to discern in any practical

way whether a student lives closer to one school than

the other. The residence standard simply does not set out

meaningful assignment criterea in such a school dis

trict.3 Furthermore, what does “closer” mean—airline

distance or road distance? There is a major highway

(No. 88) running through town upon which many students

arrive by bus, and from which the schools are approxi

mately equidistant, so that in reality, if the ground route

interpretation of distance were employed, almost all

students are at the same distance from each school (R. GO-

62, 179, 228). Even if it were possible and practical to

measure accurately the precise distance between each stu

3 In this regard it is significant that the Altheimer school complex can

absorb only a limited number of NegTO transferees and should the num

ber of applicants overcrowd the school, the Board would have an ar

bitrary discretion to limit the number of Negroes able to attend.

6

dent’s residence and the schools to do so would turn school

assignment into incredible calculations of inches and feet.

That the Board disingenuously propounds such a sugges

tion, when use of one school for lower and one for higher

grades would so conveniently result in complete desegre

gation of the system, speaks eloquently of its intention to

maintain segregation for as long as possible.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J am es M . N abbit , I I I

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

M ic h a e l J . H en ry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W a l k e b

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

D elector T il l e r

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 279