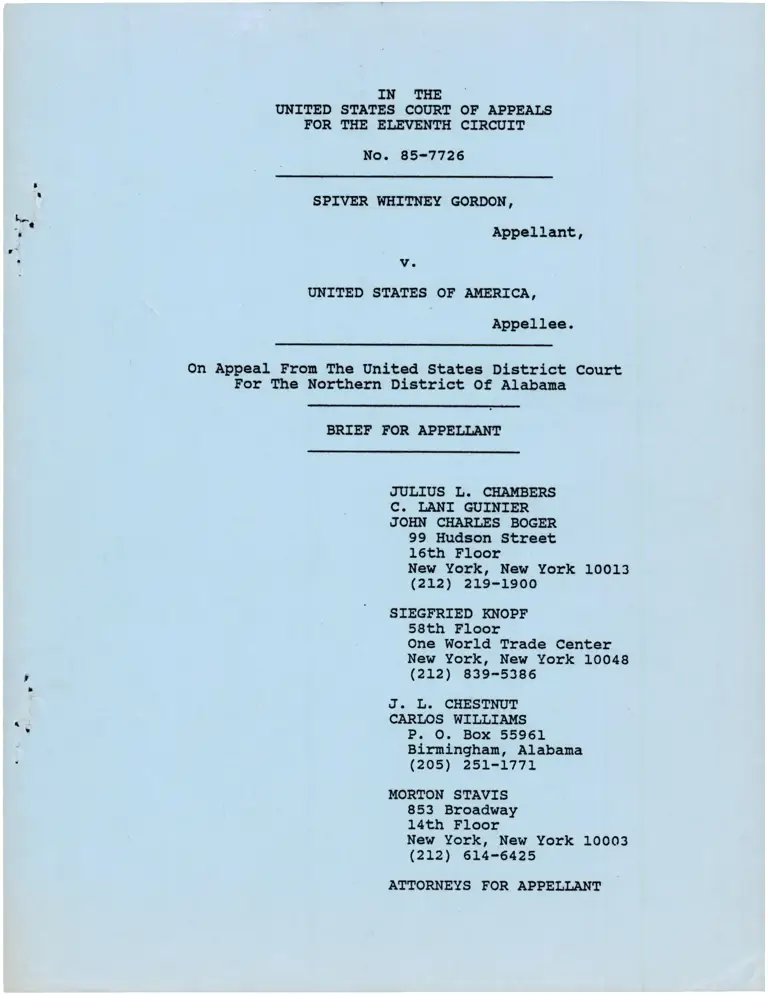

Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

June 26, 1986

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Brief for Appellant, 1986. c96d1e84-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/94d3d0c6-c1c6-4d05-9f97-18742f8b55f7/brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

t--a

a

IN TIIE

I'!{ITED SEATES COT'RE OT APPEAL8

rOR TIIE EIJE\TENTH CIRCT'IT

No. 85-7726

SPIVER WEIII!{EY GORDON,

Appellant,

V.

I'NIIED STATES OF A}TERICA,

Appe1lee.

On Appeal Frou The United States DLstrict Court

For llbe Northera Dietrict Of Alabaua

BRIET FOR APPEIJAIII

JULIUS L. CHAI{BERS

C. IJANI GUIITIER

JOHN CIIARI,ES BOGER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(2L2) 2le-Ieo0

STEGI'RTED KNOPF

58th Floor

One World [rade Center

New York, New York 1,0049

(2L2) 839-5386

J. L. CHESTNT'T

CARIOS WILIJTAUS

P. O. Box 55961

Blnninghan, Alabama

(20s1 25L-L77L

}TORTON STAVTS

853 Broadway

14th Floor

New York, New York 10003

(2L2) 6L4-6425

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELIAI.TT

J.

,

I

I STATEI.TEIIIT REGARDTNG PREFERENCE

This is an appeal from a Judguent of convlctLon on four

federal criminal counts: two counts of ual,l fraud under 18

U.S.C. S 1341; and two counts of furnishLng false inforuation

under 42 Ir.S.C. S 1973i (c). The Judguent was entered on

Novembet 4, 1985, in the Unl,ted States Distrlct Court for the

Northerrr Distrlct of Alabaua.

lhe appeal should be given preference in processing and

disposition pursuant to Rule L2 and Appendix One (a) (2) of the

Rules of the Court.

1

C

STATEITfENT REGARDTNG OBAL ARGUI.{ENT

Appellant Splver Gordon requests the Court to hear oral

argument on this appeal. The case lnvoLves a nrrmber of complex

legal issues, including a novel application by the Goverrrment

both of criminal provlsions of the Votlng Rights Act of 1955 and

of the nail fraud statute, and lssues of flrst lrnpresslon

concerning the appllcation of the Supreme Courtrs recent opinion

i.n Batson v. Kentuclrnr,

-

u.s.

-,

90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1985). The

case comes to the Court on an extenslve (20-volume) record.

Mr. Gordon beLleves that oral argument wiLl naterlaLly

assist the Court in the resolution of the issues presented. by his

appeal.

1L

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENTREGARDINGPREFERENCE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . i

STATEMENBREGARDINGORALARGITI,IENT . o........ . ii

(.

TABLEOFAUTHORITIES. O ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' '

STATEI{ENT OF EHE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVTEW . . . . . .

STATEIIENT OrTHE CASE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I. COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS IN THE COURT BEIOW . O ' '

II. STATE!{ENT OF TIIE FACTS . . . . . . . . . . . .

A. The GovernmentrE Canpalgn To Prosecute Voting

Fraud In Alabamars Blacl< Belt . . . .

B. The Governmentrs Dellberate Use Of ItrE Perenptory

Challenges To Strllce All BLack Jurors From Spiver

Gordonls Jury . o . . . . . .

C. ALabama Election Law Relevant Eo trhe Governmentts

Charges aaaaaaaoaaaaaaaaoa

D. The Evidence Presented At Trial . . . . . .

E. The District CourttE Modified Allen Charge o . . .

III. STAI{DARDS OF REVIEW . . . . . . . . . .

SUMMARYOFARGI'IIENT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STATE!{ENEOFJI'RISDICTION. . . . . . . . . .. . . . . .

ARGU!{ENTo......o..

v

1

2

2

4

4

10

15

17

25

3I

32

34

35

I . THE MAGISTRATE I S FINDTNG THAT TIIE GOVERN}IENT CHOSE TO

PROSECUTE SPIVER GORDON AI.ID OTHER BI,ACK POLITICAL

ACTIVISTS TOR ||VOTING FRAUDII WHILE OEHER SIUII,ARLY

SITUATED GREENE COUNTY RESIDENTS, WHO WERE !,IEMBERS OF A

RML,WHTTE-DOMINATED POLITICAL pARTy, WERE NOT

PROSECT'TED FOR STMII.AR ELECTION OFFENSES -- WHEN SEEN

TOGETHER WITH OTHER EVIDENCE STRONGLY SUGGESTING A

RACIAL OR POLITICAL UOTIVE FOR THE PROSECI'TIONS

REQUIRES THAT SPTVER GORDON BE ATFORDED DISCOVERY AND

AN EVIDENTIARY HEAR,ING ON HIS CI,AIM OF SELECTIVE

PROSECUTION . . . . . o . . . . r . . . . . 35

rI. THE GO'./ERNII{ENT I S DELIBERATE USE OF ITS PEREMPTORY

CHALI,ENGES TO STRIKE EVERY PROSPECTTVE BI,ACK JUROR FROM

SPIVER GORDONIS TRIAIJ JURY I'AMENTABLY CONSISTENT

WITH ITS PATTERN OF RACIAL EXCLUSIONS DURING OTHER

AI,ABAMA IIVOEING FRAUDII PROSECT'TIONS -- ESTABLTSHES A

PRI!{A FACTE VIOI,ATION BOTH OF SWATN v. AI,ABA}IA AND

BATSON v. KENTUCKY, REQUIRING A REVERSAL OF SPIVER

GORDON I S CONVICTION OR, AT !{rNrMUU, A REMAND FOR A FULL

EVIDENTIARYHEARING .......... . 40

iii

III. THE DISTRICT COTIRT ERRONEOUSIJY INSTRUCTED THE iTI'RY ON

ESSENTIAT EIJEMENTS OF EACH COUNT ON WHICH SPTVER GORDON

I{AS COTWICTED. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . o . 51

A. The False Infomatlon Offense . . . . . o . . . . . . 53

B. Thg MaiL Fraud Offgnsg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

IV. EHE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFTCIENT TO COT{I7ICT SPIVER GORDON

"T: :".T',: T',: :*.o: Y:':-Tn.'Y',.',T':YT':*. 65

V. BHE INDICTMENT FAILED TO GIVE SPIVER GORDON PROPER

NOTICE OF TIIE CHARGES ON T{HTCH HE WAS CO}IVICTED. . . . . 69

vr . tHE DrsTRrcT corrRT ' s ( 1) RErTrsAt To SEQUESTER spIvER

GORDONIS AIJL.WHITE JIIRY DTIRING ITS DELTBERATIONS IN

THrS RACTATJJY CEAP.GED CASE, (il) USE OF A PARTICITLARLY

coERcIvE !'IoDIFICATION Or rHE ALLEN CHARGE, AIID (11i)

STEADFAST REFUSAL TO DECIJARE A !{ISERIAL E[/EN AFTER A

POLL REVEATED T}IAT NINE JURORS IHOUGHT FI'RISTIER PROGRESS

ryPOSSIBLE, COI{BINED TO DEPRI\rE SPMR GORDON OF TIIE

FATR A}ID RELIABLE ,'URY VERDTCT TO WHICH IIE WAS

CONSEITTTIONALLY ENTITIJED. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . . 74

1V

TABLE OF AUTHORITTES

CASES

Allen v. United States, L64 U.S. 492 (1896) . . . . . .

Arthur v. Nyquist, 573 F.2d 134 (2d Clr.), cert. denied,

Ir.s. 950 (1978) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Batson v. Kentuclqr, If.S._r 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1985) . .

Bouie v. City of Colurnbla, 378 U.S. 347 (1963) . . . .

Bozeman v. Laubert, No. 84-7286 (Ilth Clr. May 6, L985)

slipop. at2..... ..

v. State, 28 AIa. App. 260,

PAGE

. . . 7l

439

...37

. passim

. . . .64

irigil' : . 2'n

54 U.S.L.W.

.43

.65

.67

. 31

.38

.43

.50

.64

.38

.64

.38

.43

.43

38 ,47

.50

64

64

37

38

53

43

33

Broadfoot

Brown v.

aaaaaa

L82 So. 411

Unlted States, cert. grranted, _U.S._r

3793 (U.S. June 3, 1986) (No. 85-573I) .

Burksv. UnltedStatesr 43T U.S. 1(1978) . o . . . . . . .

Cosby v. Jones, 682 F.2d L373 (Ilth Cir. L982) . . . . . .

Cuyler v. Sullivan, 446 U.S. 335, 34L-42 (1980) . . . . . .

Davis v. Schnel1, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. AIa.), aff rd, 336

Ir.S. 993 (1949) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Desist v. United States, 394 U.S. 244 (1959) . . . . .

Dunn v. United Statee, 442 U.S. 100 (I.979) . . . . .

E1lj.s v. State National Bank of Alabana, 434 F.2d 1182 (sth

Cir. 1970), cert. denied, 4O2 U.S. 973 (1971)

oaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Flores v. Pierce, 6L7 F.2d 1386 (9th Cir.), cert.

denied, 449 U.S. 875 (1980) . . . . . . . . .

Gray v. Main, 309 F. Supp. 2O7 (!I.D. Ala. 1968) . . . .

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 V.S. 218 (L964) . . . .

Griff ith v. Kentucky, cert. granted, _U. S._, 54 U. S. L.W.

3793 (U.S. June 3, 1986) (No. 85-5221) . . . . . o

Hankerson v. North Carollna, 432 U.S. 233 (L977) . . . . .

Harris v. Graddick, 593 F. Supp. 128 (U.D. Ala. 1984) . . .

Harris v. oliver, 645 F.2d 327 (sth Cir. Unit B l9B1) . .

H111 Grocer:f, Co. v. State, 26 AIa. App. 3O2, 159 So. 269

(1935) . . . . . . . .

Holcombe v. Mobile County, 25 Ala. App. 15I, L55 So. 638,

cert. denied, 299 AIa. 77, 155 So. 640 (1934) .

Hunter rr. Erlckson, 393 U.S. 385 (L969) . . . . . . . o

Hunter v. Undernrood, _ U.S. _ 85 L.Ed.2d 222 (1985)

In re Winshipt 397 Ir.S. 358 (1970) . . . . . . . . . . . 33,

Ivan V. v. City of New York, 407 U.S. 2O3 (L972) . . . . . .

Jacksonv. Virginia, 443 U.S.3O7 (L979) . . . . . . . . .

Jenkins v. United States, 380 U.S. 445 (1955) (per

cUriam) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7L

Lee v. Nyqrrist, 318 8. Supp. 7LO (W.D.N.Y. I97O), aff td, 4O2

u.s. 395 (197L) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Mackey v. United States, 401 U.S. 667 (197L) . . . . 43

Marks v. Unlted States, 430 U.S. 188 (L977't . . . . . . . ,64

IttcCray v. Abrams, 75O F.2d 1113 (2d Clr. 1984), cert.

pending, (No. 84-1426). . . . o . . . . . . 45

Morissette v. United States,342 U.S. 246 (l.952) . . . . . 54,60

People v. HaII, 35 Ca1. 3d 161 , L97 CaI. Rptr.7L, 672

P.2d 854 (L983)(en banc) . . . . . . . . . . 45

People v. Whee1er, 22 CaI. 3d 258 , L48 Ca1. Rptr. 890, 583

P.zd748 (1978) . . . . . . . . o 45

Powell v. United States, 297 F.2d 318 (5th Cir. I96L) . . . .

Pullnan-Standard v. Swlnt, 456 U.S. 273 (LggZ) . . . . . . .

Resident Advisory Board v. RLzzo, 564 F.2d 126 (3d Cir.

L977) , cert. denied, 435 U.S. 909 (1979) . . . . . 37Russellv. UnitedStates,369 U.S.74g (1962) . . . . . . . . 70

Sandstrom v. Montana, 442 V.S. 510 (1979) . . . . . . . . . . 53

Shea v. Louisiana, _ U.S._r 84 L.Ed.2d 38 (1985) r . . . . 43spinkellink v. Wainwright,-Eze F.2d 592 (5th cir. 1978),

cert. denled, 44O U.S. L976 (1979) . . . . . . . . 37

State v. Gllnore, L99 N.J.Super. Ct. App. Div. 3gg, 499 A.2d

1L75, cert. granted, 101 N.if . 295, 501 A.2d 949(1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Stirone v. Unlted States, 361 U.S. zLZ (1960) . . . . . . . . 70

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) . . . . . . o . . . passin

UnitedStatesv. Albanezr 4SO U.S.333 (1991) . . . . . . . o 54

United States v. Alonso, 74O F.2d 962 (Ilth Cir. 1994),

cert. denledr _If .S._r 83 L.Ed.2d 939

- (1985) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34r7!r7lr72

United States v. Amaya, 509 f .2d 8 (sth Cir. 19ZS) . . '7O',7L',73

United Stateg v. Balley, 460 F.2d 518 (sth Clr.

L973 (en banc). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Or7L

UnltEd StateE v. Ballard, 663 F.2d 534, (sth Clr. Unlt B

1981) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6].

United States v. Bell , 678 F.2d 547 (Sth Clr. Unit B

L982) (en banc) , aff fd on other grounds , 462

u.s. 356 (1983) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65United States v. Berrigan, 492 F.2d L7L (3d Clr. Lg73) . . 39United States v. Berrios, 501 F.2d L2O7 (2d Clr. Lg74i . . . 39United States v. Bownan, G36 F.2d lOO3 (sth Clr. Unit-a

1981) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Brldges, 493 f.2d 918 (Sth Cir. Lg74) . . .

United States v. Caumlsano, 546 E.2d 238 (Bth Cir. Lg76)

United States v. CaEtIe, No. 82-5011, decid,ed August L2',

1982 (5th Clr.)(unpublished) . . . . . . . o . 59United States v. Clapps, 732 F.2d L14g (3rd Cir.), cert.

denied, _U.S._r 83 L.Ed.2d 699 (1994) . . . 59rGOr6g

United States v. Curry, eal f.2d 406 (sth Cir. I9g2) . . 59, 62United States v. Davis, 679 f.2d 945 (ILth Cir. 19Bi), cert

denied, 459 U.S. L2O7 (1983). . . . o . . . . . 69United States v. Di Bernardo, 775 F.zd L47O (lLth

Cir) (1985), cert. deniedr _US_, 9O L.Ed.2d 357

7L

50

54

60

39

(1986). . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . .

United States v. Dixon, 536 F.2d 1389 (2nd Cir. 1976) .

United States v. Erne, 576 ?.2d 2L2 (gth Cir. I9Z8) . . .

United States v. Figueroa, 666 F.2d L37S (lLth Clr. 1982)

United States v. Forrest, 620 ?.2d 446 (sth Cir. IggO) .

United States v. Gonzalez, 66I F.2d 489 (sth Cir. Unlt g

198].) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

United States v. Hastings, 451 U.S. 499 (1983) . . . . o

United States v. llazel , 696 F.2d 473 (6th Cir. 1983). . .

United States v. Howard, 774 F.2d 838 (7th Cir. I9g5) . .

United States v. Johnson, 7L3 f .2d 633 (l,Ith Cir. 1993),

cert. denied.465 U.S.1081 (1984)... o...

United States v. Klein, 5I5 F.zd 751 (3rd Cir. L}TS) .

United States v. Krej.mer, 609 f.2d L26 (Sth Cir. IggO)

United States v. Leslj.e, 759 F.2d 366 (sth Cir. 1985),

..51

50

..39

..70

66, 5g

69

39

54

70

..69

59

vl-

revrd, 783 F.2d 541 (1986)(en banc) . . . . . . . L2,SL

Uni.ted States v. Lewis, 5L4 F. Supp. 169 (M.D. Pa.

1981) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . r . . 59

United States v. Longoria, 569 g.zd 422 (sth Clr. 1978) 68

United States v. Mandel, 591 F.2d L347 (4th Cir. L979),

cert. d,eniedr 445 U.S.96L (1980) . . . . . . . . . 61

United States v. Murdock, 548 F.2d 599 (sth Clr. L977) . . . 39

UnitedStatesv. Nixonr 418U.S.583 (1974) ... . . .. .. 40

Unj.ted States v. OrMa1ley, 7O7 f.2d L24O (Ilth Clr. I9B3) . 58159

United States v. Odom, 736 F.2d 104 (4th Clr. 1984) . . 59,62,68

Unlted States v. Olinger, 759 F.2d 1293 (7th CJ.r.),

cert. deniedr _If .S._r 88 L.Ed.2d 98 (1985). . . . 54

United States v. Outler, eSg F-.2d 1306 (sth Cir. Unit B

1981) . . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . 70

United States v. Prentiss, 446 F.zd 923 (5th Cir. lg7l) . . . 73

United States v. Price, 623 F.2d 587 (9th Cir.), cert.

denied, 449 U.S. 1016 (1980). . . . . . . . . . . 59r69

United States v. Resnlck, 299 Ir.S. 2O7 (L93G) . . . . . . o o EO

United States v. Roblnson, 311 F. Supp. 1063 (I{.D. Mo. 1969) . 35

United States v. SaLlnas, 654 F.2d 319 (Sth Cir. Unit A

1981) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

United States v. States, 488 F.2d 761 (Bth Cir. Lg73'), cert.

denied, 417 U.S. 909 (L974) . . r . . . . . . . . 59

United States v. Eaylor, 530 F.2d 49 (sth Clr. Lg76) (per

curiam) . . o . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34r7lr72r73

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 564 F.2d L62

(sth Cir. 1977) , cert. denied, 443 Ir.S. 8Is(1979). . . . . . . .

United States v. Turner, Hogue and

00014, (S.D. A1a. July 5,

ro"i.i,'c;.'N;.'B;-' ' 38

1985) (jury verdict of

. acquittal) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . L7r63united states v. washingiton, 688 F.2d 953 (sth cir. 1982) . 62united states v. I{iltber9€r, 5 wheat. 76 (1820) (t{arshaLll

C.J.) . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . , 60

United States v. Zicree, 605 F.2d I38I (sth Cir. LgTg),

cert. denied, 445 Ir.S. 966 (1980) . . . . . . . . . 59

Vasquez v. Eillary, _U.S._r 88 L.Ed.2d 599 (1986) . 4IVillage of Arlington Helghts v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corps., 429 U.S. 252 (L977) . . . 3g

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (f975) . o . . . . . . . 39

Washington v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, 459 U.S. 457

(1992) ... r........ . o ... 37

Wayte v. United. States, If .S._r g4 L.Ed.2d 547

(1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32135136

Willians V. Wa1lace, 24O F. Supp. l.OO (U.D. AIa. 1965) . . 3g',47

Willis v. Zant, 72O F.2d L2t2 (ltth Cir. 1983),

cert._denied, 467 U.S. L2S6 (1994) . . . . . . . t2,42Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) . . . . . 32t 35',36

Zayre of Georgla, Inc. v. City of Atlanta, 276 F. Supp. ggz

STATUTES PAGE

IBU.S.C.S1341.......o....passim

42 U.S.C. S1973i(c). . . . . o . . . o . . . . . . . .. . passin

35

vii

LEGISI,ATTVE HISTORY PAGE

Civil Rights InplicatlonE of Federal Votlng Fraud Prosecutions:

Ilearings Before the Subcomn, on CiviL and Constltutlonal Rlghts,

House Conm. on the JudlcLar?, 99th Congf ., lst Sess. 1985

(forthcoming). . . . . . . . . . . o . . . . . . . . . .

111 Cong. Rec. 58423-33, 58813-17, 58984-88, (April 26,

28, April 29, 1955). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

111 Cong. Rec. tll6246-49 (JuIy 9, 1965). . . . . . . . .

OTHER AI'THORITTES

. . .40

April

..55r56

. 55r 56

PAGE

United States Department of Justice, Federal ProEecution of

Election Offenses (October, 1984). . . . . . . . . . . . . .55

vLl-l-

UNITED

FOR

IN THE

STATES COURT OF APPEATS

THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-7726

a

SPIVER WHITNEY

v.

UNITED STATES

GORDON,

AppelIant,

OF AMERICA,

Appellee.

On Appeal From The Unlted States

For The Northern District of

Dlstrlct Court

Alabana

STATEMEI{T OF THE TSSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIE}I

1. Did the Dlstrlct Court err ln refuslng despite

Eubstantial evidence of a proeecutorlal canpaign guided by racial

and political crlteria to permit Mr. Gordon any dlscovery of

the Government and/or any evldentiary hearlng on hls clalm of

selectlve procrecutlon?

2. Dld the Government's systenatlc uae of its

peremptory challengee to exclude every black Juror presented to

1t establlsh a prima facle violatlon of Equal Protection

standards established in Batson v. Kentuckv,- U. S.-,

69 (1986), of,, in light of the prlor pattern of racial

the companlon "voting fraud" cases, under the standards

v. ALabama, 38O U.S. 2O2 (1965)?

90 L. Ed. 2d

strikes in

of Swain

3. Did the Distrlct Court's mens rea instructions on

the mail fraud and false informatlon counts which effectlvely

permitted the Jury to convict Mr. Gordon upon proof of any

technical vlolatlon of AJ.abama state election provlsions, and

absent proof of specific lntent to defraud -- misinterpret

applicable federal statutes and violate Mr. Gordonrs federal due

procesa rights?

4. Is the record evidence against Mr. Gordon, viewed

in the light most favorable to the Government, nevertheLess

lnsufflclent to permit any reasonable jury to convlct him beyond

a reasonable doubt?

5. Was Mr. Gordon denied his due Procesa right to

notice of the charges agalnst hin by the variance between the

offenses set forth in his lndictment and the Dlstrlct Courtrs

constructlve amendment of those offenses in its instructions to

his jury?

6. Dld the supplenental instruct j.ons glven by the

District Court to Mr. Gordonrs Jury, after lt reported that it

was "hopelessly deadl.ocked" durlng lts deliberatlons including

its modified AIlen charge and the judgers expression cf a

personal opinlon on the value of further dellberatlons -- violate

the strict constraints imposed by this Court in prior cases?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. COURSE Otr PROCEEDINGS IN THE COURT BELOW

Appellant Spiver 9{hitney Gordon was lndicted on thirty-seven

varied federal criminal. counts for his activity in assisting

black absentee voters in a primary election in Greene County,

Alabama. The Government disnissed slxteen counts against Mr.

Gordon prlor to trial because of a lack of evidence; he was tried

on twenty-three counts in the Northern District of AJ.abama.

Prior to trlal, Mr. Gordon petitioned this Court for a wrlt of

mandamus and prohlbition, seeking to preclude the Government from

exercising its peremptory strikes in a racially discriminatory

manner. That petition was denied by a panel of the Court on

September 29, 1985. The Asslstant United States Attorney

exerclsed alt slx of hls perenptory challenges to remove every

black venireperson from Mr. Gordonrs iury.

Trial before the all-white jury proceeded for eighteen days,

lncluding five days of dellberations during whlch the Jury which

was glven a modifled "Allen charge." Mr. Gordon was ultlmately

acquitted of fourteen counts, but was convlcted -- on two counts

of mail fraud and two counts of furnlshlng false information to

an el,ectlon official

submltted on behalf of

Government motlons to

preJudice. (R1-85) .1

for witnesslng two absentee baLlots

hls wlfefs uncles. The Court granted

dlsnlEs flve additlonal counts with

Mr. Gordon filed tlnely written motions

for judgment of acqulttal (R1-73) and for arrest of Judgment (R

t-72), which the Court denled. (R1-74, 75).

The Court sentenced Mr. Gordon to a $5O0 fine on each of two

counts of nail fraud and to three year concurrent sentences on

all counts, suspending all but the first six months, with three

years probation following release from custody, including five

hundred hours of community servlce. (R1-?7).

On November 14, 1985, the district court stayed execution of

Mr. Gordon's sentence, pending this appeal. (R1-76).

1

by the

document

the page

Each reference to the Record on Appeal wiJ.l. be indlcated

abbreviation "R," followed by the volume number, the

number (if the volume contains multiple documents), and

number on which the reference may be found.

II. STATEMEI{T OF THE FACTS

A. The GovernmQntrs Canpaign To Prosecute

Votlng Fraud In Al.abama I s Black Belt

Spiver Gordon and a co-defendant, Frederlck D. Danlels, were

lndlcted at the requeet of the United Statee Attorney for the

Northern Dlstrlct of Alabana for alleged acts of "voter fraud"

and urall fraud ln connection with a Septenber 4, 1984 primary

electlon heLd ln Greene County and throughout the State of

Alabama and a September 25, 1984 run-off electlon ln that county.

(See R1-1-1). The lndlctrnents were among a series of slmilar

federal chargee preesed ln mld-1985 agalnst at leaet elght

Alabama citizens (R3-30-33), all resldents of, flve counties ln

Al.abama's so-called "Black BeIt" (herelnafter "the voter fraud

cases" ) .

Alabana's "Black Belt" ls distinguished by the high

percentage of black cltizens among lts ten counties.2 In the

decades prior to enactment of the Votlng Rights Act of 1965, all

of these counties were pollticalty domlnated by the ninority of

whlte voters; the black maJority was effectlvely shut out of all

participatlon ln the electoral process. (RS2 Fact Sheet, 61t 1)3.

2 According to the 1980 U.S. Census, the percentage of

blacks in A.l.abamars ten Black Belt counties is as f ollows:

Choctaw (43.46); Dallas (54.53); Greene (78.0O); Hale (62.8O);

Lowndes (?a.98); Marengo (53.28); Perry (60.08); Plckens (41.8O);

Sumter (69.26); and Wllcox (68.80).

3 Each reference to the materlals submitted to the Dlstrlct

Court under seal ln support of Mr. Gordon's selectlve prosecutlon

clalm w111 be lndicated by the abbreviatlon 'rRS'r followed bY a

number rr 1rr or tt 2tt f or the f irst or second submlssion--

foll.owed by some ldentlfying informatlon. (As the Magistrate

noted in his Recommendation on thls claim, these documents were

"filed under seal in order that defense strategies wilJ. not be

compromised. " (R1-50-8 n.2 ) . Although the trial has been

completed, Mr. Gordon intends to honor the seal by identlfying

Since the 1965 Votlng Rlghts Act as the Unlted States

Maglstrate who heard Mr. Gordon's claln of sel.ectlve prosecution

found ',there has been an intense struggle between whltes and

blackE ln the Alabama Black BeLt wlth whlte persons seeklng to

retain polltlcal power and blacks seeklng to share ln lt." (R1-

50-13). "According to [Mr. Gordon's] affldavlts, " the

Maglstrate noted, "one nethod used by whltes for many years, "

"lnvol.ved the 11legal voting of absentee ballots." (Id. )

In the late 196Os in Greene County, slates of black

candidates were elected to a naJorlty of countywlde offlces for

the first tlme. By t982, blacks had obtalned polltlcal control

of county commlsslonE and school boards ln flve of the ten Bl'ack

Belt counties. (RS2 Affrt of Ira 8., at 5; see also RS2 Fact

sheet, €rt I). In Greene County, the princtpal polit1cal

organlzation representing these black lnterests was the Greene

County Civic League ( "GCCL" ) (RSl- Aff I t of Debra H. , at 2) .

Spiver Gordon, a fornrer offlclat of the Southern Christlan

Leadership Conference, was a principal leader of the GCCt and, at

the tlme of hls indictment, had become the Director of the

Community Service Block Grant Program, a member of the Greene

County Hospltal Board, and a deputy registrar for the Greene

County Board of Registrars. (R1-1-2). As an officer and the

"spark pfug" of the Greene County Civlc teague, Mr. Gordon was

extremely well-known throughout the area. One witness testified

that some blacks called Mr. Gordon the "black Moses" of Greene

County. (R13-e1).

accompanylng documents ln an abbrevlated form, u-:- Aff 't of

B. )

the

Ira

. In the spring of 7984, a rlval polltlcal organlzatlon, the

People's Action Committee (IPAC"), eras formed in Greene County.

(See RSl, Aff't of Debra H., L-2; Exh. !, newsPaper article

entltled "New PAC cl,ains runoff wln" ) Its menbershlp and support

was predomlnantly among whlte voters (RS2, Affrt of lra B., at

7t', although a selected number of blacks were recrulted to the

PAC, lncludlng John Klnnard. (RS1, Aff't of Debra H., at 2t,.

Anong the co-founders and leading members of the PAC was an

assistant Dlstrict Attorney in Greene County, 9{alter Griess.

(RS1, Aff 't of Susan J., at 4, & Exh. 1).

Mr. Gordon's evidence demonstrated that durlng 1984, the

Unlted States Attorneys for the Northern and Southern Dlstrlcts

of Alabama began an lntensive lnvestigatlon of votlng fraud ln

A]abama. The lnvestlgatlon was concentrated excluslvely on

Alabamars Black BeIt (RS2, Affrt of Ira 8., at 2; RS2 Fact Sheet

at Z), and within the Black Bett, excluslvely on those flve

counties In which black cltizens had obtalned naJorlty control of

county offlces. (RS2 Fact Sheet, €tt 2; RS1, Aff rt of Dennis S.,

Aug. 8, 1985, :rt 1). Moreover, within those five counties,

federal attentlon focussed solely on those officials,

predominantly black, who were the leaders of the majority

faction. (RS1, Aff't of Susan J., at t-2; RS2, Fact Sheet,3-41.

grlithln Greene County, Mr. Gordon showed that scores of

substantlal. allegations of voter misconduct by PAC offlcers and

members, though reported to investigating officlals (see, €.o. r

RS2, Aff I t of Ira B. , 13-28 and accompanylng affidavlts; 99e,

e.ct., RS1, Aff 't Dennls S., Aug. 2, 1985, Et 2; RS1 Aff rt of Ruth

H., 7-2\, went unlnvestlgated, even as intense scrutiny was

directed toward GCCL leaders and their followers. (RSl, Affrt of

Dennls S., Aug. 2,1985, at t; RS2, Fact Sheet, S-41.

Mr. Gordonts evidence revealed that prominent nembers of the

rlval PAC, lncludlng assistant dlstrlct attorney Walter Griess,

worked directly with E'BI agents and offlclals of the Department

of Justlce ln the investlgatlon of GCCL members. (RS1, Affrt of

Susan J., at 3i 1d. Aff tt of Ruth H., at 4) ("Mr. Grless stated to

me that he was 'the conduit' for conplaints that trlggered

the F.B.I. lnvestigatlon") (RS2; Aff't of John 2., at 10)("Grelss

[sic] was also present wlth the F.B.I. agents that ralded [the]

office of a member of the GCCL.") Mr. Gordon'E evldence revealed

that another PAC member, John Klnnard, stated publicly that he

was "directlng the federal effort." He had been seen repeatedly

"meetlng with FBI agents." (RSl, Aff't of Deborah L., at 5).

Thls intensive lnvestigation, €rs indlcated, eras part of, a

broader effort throughout the Black Belt. One official, the

Asslstant Dlrector of the Offlce of Publlc Affairs of the

Department of Justlce, reportedly explaJ.ned the lnvestlgations as

part of a "new pollcy brought on by the larrogrance on the

part of blackst ln these counties." (RS2, Aff't of lra B., at 2l,.

The resuLt of the lnvestigations characterized by widespread

FBI lnterrogatlon of black voters, many of them elderly, rural

citizens (RS1, Aff't of Susan J., at 6) -- was the lndictment of

seven black civll rights Leaders (and one white synpathlzet) ln

these countles. (R3-3O-33) .

Shortly after her lndlctment, Bobbie Simpson filed a motlon

to dismiss on grounds of "selective and lnvldious dlscrininatory

prosecution, " annexing a substantlal number of documents as prlma

facie evldence of her clalm. Mr. Gordon subsequently moved on

July 29, 1985, to adopt by reference the substance of Ms.

Simpson's motlon. (Rl-19). In a second motlon, Mr. Gordon

repeated hls reguest and alleg€d, as addltlonal evldence relevant

to h1s case , that "9{hi tes who were pol ltlcal rivals of

Defendantt I aaslsted and were lnvolved ln the absentee votlng

process wlth the ldentical tsicl nurslng home patients"

respectlng whose ballots he had been charged, al.though the whites

,'were not charged and lndlcted." (R1-24-2). On Augiust gth, Mr.

Gordon agaln moved to dlsmiss his lndlctnent. (R1-29-2). The

Unlted States Maglstrate heard oral argtument, and on Auguet 12th

granted Mr. Gordon's motlon to adopt by reference Ms. Simpsonrs

earller motlon. (R1-35). He also permltted counseL untll August

l6th to submlt further evldence rel.evant to hls flnaL decision on

whether to allow defendants to conduct dlscovery of the

Government and/or to permit a full evldentiary hearlng. (R1-39-

21 .

As explalned ln the affldavlt of attorney Ira B. (RS2), a

smalI group of untralned researchers, armed with basic documents

and informatlon concernlng the Greene County prinary, was able

between August L2 and 16 to ldentlfy: (i) PAC members who had,

according to registered voters, fraudulently cast absentee

ballots ln false names (see RS2, Affrt of Ira B., 14-15, 17-18);

(iiy pAC candidates who had, ln apparent vlolatlon of Alabama

Jaer, particlpated 1n the absentee ballot process (ld. at 16);

(111) a Circult Clerk, a PAC member, who had lmproperly

notarized absentee ballots (l.g!. at t9'2t); (iv) whlte residents

of other states who had apparently been provlded by the PAC

Clrcult Clerk wlth absentee ballots ( id. at 231; (v) other

absentees who reported that they had never received anv absentee

ballot for the 1984 prlmary, yet whose ballot and affldavlt were

recorded ag havlng been witneseed by the PAC Clrcult Clerk (1d.

at 25\; and (v1) ballots that e'.ere defectlve lacklng elther a

witness slgnature, other requlred data or even a name for the

voter -- whlch were voted by PAC supporters. (Id. at 26).

Counsel also located dozens of black citlzens who had reported

PAC abuseE to FBf agents durlng the lnvestigation. None of the

reports were acted upon. (Id., 13-14).

After conslderlng thls uraterlal, the Magistrate acknowledged

that "the defendants have made a showing of a 'colorabJ.e

entltle6entr" to relief under "the first prong of the selectlve

prosecution Istandard]" (R1-5O-12) that ls, they had shown

,'that whlle others simllarly sltuated have not been proceeded

against, [they have] been singled out for prosecution."

(Id. at 4).

However, the Maglstrate decl.ined to flnd sufflclent evidence

that ,,the decision to prosecute $ras invidious or in bad faith

because based upon some lmpermlssible factor such as race

or the exercise of constitutional rights. " (8. 4, 15)' It

erras "Clear," he Observed, that "no serious schOlar woUl'd ever be

tenpted to point to the areas covered by these materlals as

paradigms of democratlc government, " ( id. at 13) , but he

discounted the public remarks of federal Iaw enforcement

officlals that the campaign was airned at "arrogant blacks",

questloned the obJectivity of several defense affiants, noted

that ',no PAC person 1s claimed to have been involved with more

than two unlawful ba]lots, " ( ld. at 8) , and pointed out

that only "Is]lx persons aIlegedly affl]lated wlth the oppositlon

(PAC) alLegedly comnitted acts slmilar to defendants."

(Id. ). He ultimately dlsmlssed other defense evldence as

" [n]othlng more than technlcal. vlolatlons of Alabarna Law. " ( Id.

at 9).

Havlng denled all dlscovery or any evldentlary hearlng, the

Magistrate recommended that Mr. Gordon's motion be overruled.

(Id. at 16; see also R1-52-?). The Distrlct Court accepted the

Maglstrate's recommendatlon 1n a summary order, entered August

26th. (R1-5?). Following the trla1, Mr. Gordon relterated this

clalm, ln hls motion for Judgnent of acqulttal. (R1-?3-1-21. The

Distrlct Court sumnarlly overruled the notion. (R1-75).

B. The Govcrnnent'g Dcllberate Use Of

Its Perenptory Challenges To Strlke

All Black Jurors From SPlver

Gordonrs Jury

In the two Greene County voting fraud trlals that preceded

Mr. Gordonrs, the Government chose to exercl.se lts perenptory

chal.lenges 1n an unmistakably raclal pattern. "In the Colvln

case, " defense counsel informed the Distrlct Court, "five of the

slx pre-emptory Isic] challenges were used to strlke black Jurors

from the Jury. In the Simpson case, four of the six were used to

strike black Jurors from the JurY. In other words, out of twelve

challenges in the preceding two caaes, nlne were exercised

against black Jurors." (R3-62).

AJ.erted by thls prior pattern, Mr. Gordon f lled a timely

written motion on September 23, 1985, "to preclude the United

States from exercislng its peremptory challenges in a racially

discrirninatory manner. " (R1-7O-9O) . During oral argument in

10

support of the motlon, counsel for Mr. Gordon contended that the

pattern of Government strikes ln the Colvin and Slmpson cases

constltuted "a prlma facie showlng, stronger than in any of the

other cases we clte tlnl . our motl.on, of a dlscrlminatory

use of a pre-enptory challenge." (R3-63).

The Dlstrlct Court decllned to 'rassume from the outset that

. the Government lntends to exercise lts pre-emptory

challenges ln a raclally discrimlnatory manner, rr (R3-64), and

therefore overruled the motlon. (Id. at 55). 9{h11e the Court

lndlcated that Mr. Gordon $raE free to reaseert the clain during

the Jury selectlon process, it acknowledged an underlylng

convlctlon that "[a]ny time that a Court moves ln and tells the

Government . how to have to exercise thelr pre-enptory

challenges, based on assumptlons, Ithat] is Just a bad

sltuatl,on." (Id.).

Followlng the Courtrs dlspositlon of other pretrial

motlons,4 ln a post-lunch chambers conference, counsel for Mr.

Gordon noted for the record that only 7 of the 61 members of the

venlre, o1. 11 . 3 percent , were black persons, ( R3-83 ) , a'n

underrepresentatlon of 7 percent from the Jury-eliglbIe

populatlon, and then moved to quash the veni.re, expresslng

,,particular[ ] concern[ ] because the Government has six strikes

4 prior to triaL, Mr. Gordon f il.ed a Jury composition

challenge to the Jury selectlon procedures of the Northern

Dlstrlct, (R1-12), partly on the ground that the dlstrict-wlde,

used in lieu of a dlvlsion-wlde, selectlon system reduced black

representatlon on the quatifled wheel. (1SR-t-tl9-27). One of

the court officials responslble for administerlng the plan

testifled that he belleved the declslon not to select Jurles by

dlvlslon was based on the large number of blacks in some

divislons (such as the 9{estern Divlsion which lncludes Greene

County. ) ( Id.)

11

and there are seven blacks out there." (R3-84).

overruJ,ed. (R3-85).

The motlon was

Two days later, after completlon of the prellminary volr

dlre process, the Government and defenEe counsel each exercised

thelr respectlve peremptory challenges. Over contlnued defense

obJection, the government used each of its six peremptory

chal.lenges to remove, one by one, each black Juror that came

before it. Defense counsel obJected to each excluE.lon, noting

after the Governnent's last challenge:

Thls meana that six out of six [Governnent]

challenges have been used exc.luelvely agalnst

blacks. TheEe are the only six Jurors and

the Government has used all of thelr strlkes

on these sLx, Ieavlng the iury totaJ'ly white.

(R5-2O3). Defense counsel voiced a final, omnlbus obJectlon,

renewing aII motions previousl.y made to the practlce and adding

"a notlon for dlsmlssal of the Indictment on the grounds of

prosecutorlal misconduct and racially motlvated use of peremptory

chaJ.lenges.... " (R5-204). Each defense motion was sumnarlly

overruled by the District Court without explanatlon. (R5-2OO-O4).

The followlng mornlng, September 26th, Mt. Gordon once again

renewed his objection. (R6-14-3O).5 Treating counsel's request

5 Counsel flrst called the Dlstrlct Courtrs attention to

the then-recent holding in McCrav v. Abrams, 75O F.2d 1113 (2d

Cir. 1984), cert. pendinq, (No. 84-L4261, which announced a new

federal procedure for examination of racially suspect

peremptories, grounded ln Sixth Amendment concerns. (R6-19). He

next argued that even under the equal protection standards set

forth ln Swaln v. Alabama, 38O U.S. 2O2 (1965), as interpreted by

this Court in Wlllls v. Zant, 72O F.2d t2L2 (11th Cir. 1983), he

had made out a prima facie case requiring a full hearlng in

light of the Governmentrs excluslon of every prospective black

juror from Mr. Gordon's case. (R6-2O). Flnally, citing the panel

opinlon |n Unlted States v. Leslle,759 F.2d 366 (sth Clr. 1985),

rev,d,783 F.2d 541 (1986)(en banc), counsel urged the District

Court to exerclse its supervisory powers to lnquire lnto the

Government's pattern of racial exclusion:

t2

as both a motlon for reconslderatlon of its prior ruling and as a

separate notlon, the Court summarlly denled the rel.lef requested.

(R6-28; ld at 29l'.

Counsel then sought a contlnuance or a stay from the

Distrlct Court in order to obtaln an imnediate rullng on the

lssue from thls Court. (R6-29-30). The Government responded

that lt would make a record "so that Defense can gee the reason

that we exerclsed those strl.kes. " ( R6-3O ) . Among lts

explanatlons, the Government clalmed that lt struck Juror No. 60

because lt 'rwas satlsfled she was being evasive ln anEwers posed

to her. "

Counsel for the Government contlnued:

Juror No. 26 was struck bacauEe he was

observed comlng lnto the courtroom before the

venlre was called out, puttlng his arm around

one of the'defendants, shaking hands wlth the

defendant and exchanglng greetings.

Juror No. 35 $ras struck because she had the

Lowest educatlon of anyone on the venlre,

[and] ... [91]hen asked about her dclay ln

votlng, she expressed a biae wlth regard to

not knowlng that she had the right to vote--

as I recall, her words were that they coul'd

vote, or had the right to vote.

(R6-31-321.

The Court responded, without elaboration, "Well, the Court's

So we would ask the Court for a hearlng, for

a dismlssal of the Indlctment, first, for a

mlstrial, second, and at Least, for a

mlnlmum, for a hearlng on the question of

what motlvated the use of pre-emptory

challenges yesterday by the Unlted States

Attorneys.

13

( R6-27 )

rullng remains the same." (Id. at 33)

Defense counsel imnediately rebutted these explanations with

an evidentiary proffer:

I betieve the [Government's] statement, Your

Honor does glve rise to the necd for a

hearlng . Because there lsn't a basls for

what the U.S. AttorneY ls saYlng.

THE COURT: I have already ruled wlth respect

to the hearlng. And my ruling remalns the

same, Mr. Welnglass.

*

MR. WEfNGLASS: Your Honor, f proffer to the

Court that lf such a hearing were he1d, w€

would be able to produce testimony to the

effect that even before the venire was

brought lnto this courtroom on Monday

mornlng, lt was the lntentlon of the Unlted

States Attorney to strlke every black from

thls Jury and to send these defendants to

trlal before an all-whlte JurY.

Your Honor, the statements made about Harold

HalI, juror No. 26, that he embraced the

defendant, that never occurred. And the

defendant will testify in a hearing that he

has never touched, seen or spoken with this

man.

THE COURT: I am through with thls issue.

Now, I have ruled, ME. gileinglaas. 9{ith all

due respect to you and your co-counsel, I

belleve that you have got your matters stated

of record. And the rullng has been made by

the Court. And that is my rullng. And I

want to move on wlth the trlal, please; wlth

all due deference to Counse] for the

defendants.

(R6-34-36). (The full exchange between the Government, defense

counsel and the District Court is set forth in the Record

Excerpts, 68-91. )

The District Court entered a brlef wrltten order later on

the basic facts and denied the

t4

September 26th, which recited

motlons for an evldentlary hearlng, f,or dlsmissal of the

lndlctment, and for a mistrlal. The Dlstrlct Court offered no

1egal basis for lts rulings. (R1-7O-81).

Serlously concerned over the proepect of facing an all-whlte

Jury to answer federal charges alleglng that he and other black

votlng rlghts actlvlsts had consplred to defraud the local

electorate, Mr. Gordon filed a petltlon wlth thls Court later ln

the day on September 25th. He sought "a Wrl.t of Mandamus and

Prohibitlon pendlng determlnatlon by the Supreme Court of

the Unlted States of Batson v. Kentuckv, cert. qranted, 84-6263'

gZ Cr. L. Rptr. 47 (Aprll 22,1985), or alternatlvely, conpelllng

Respondent to hold a hearlng to determine whether the actlons of

the Assistant U.S. Attorney in exerclslng peremptory challenges

to exclude all black Jurors !n [hls] trlal deprived [hlm]

of rlghts secured by the Flfth and Slxth Amendments to the

Constltution. " A pancl of this Court entered a one-line order on

September 27, 1985, denying the petltlon. (R1-70-741.

Mr. Gordon was ln fact trled by an all-whl,te Jury. After a

verdict had been entered, h€ moved for a Judgrnent of acqulttal

Or., in the alternatlve, for a new trlal, once agaln seeking an

evldentlary hearlng or substantlve rellef. (Rl-?3-1 ) . The

District Court overruled the motlon, otl Notrember 13, 1985,

holding simply that "no evldentlary hearlng 1s requlred Iand]

. that the allegations therein contalned are

merlt." (R1-?5-1).

. wlthout

C. Alabama Electlon taw Relevant

To The Governnentrs Chargee

According to the evldence adduced at trlal, a reglstered

voter in Greene County is entitled to vote by absentee ballot ln

15

the county if physlcally lncapacttated or if absent from the

county on electlon day. Under Alabama law, a registered voter

1lvlng outslde Greene County can lawfully vote ln county

electlons so long as he is not reglstered elsewhere and conslders

Greene County hls legal domlclle. (R16-21). An applicatlon to

the appropriate county offlclal, Mary Snoddy, the Absentee

Election Manager, for an absentee ballot must be ln wrltlng.

(R6-1741. Upon recelpt of the appllcatlon, and after checklng

whether the appllcant ls registerad to vote ln Greene County (R6-

t781, Ms. Snoddy forwards a klt to the voter at the malling

addrees lndlcated on the appllcatlon. (Id. at 179). Ihe malling

address may be, and often ls, other than the voterfs own

resldence. (R7-10O; R12'124; R12-7521, The kit contains two

envelopes and a ballot. (R6-1?9). On the printed side of the

ballot are the names of the candldates, wlth a place for the

voter to indicate a choice. Once the ballot ls voted, it is

placed ln a sealed envelope, "the secrecY envelope." (R6-185).

This envelope normally contalns no ldentlfylnE marks or writing.

The sealed secrecy envelope ls then deposlted in a larger

,'mailing envelope" addressed to the AbEentee Electlon Manager.

On the back of the maillng envelope is an affldavlt with blank

lines for the slgnature or mark of the voter, and for the

slgnature of a notary or two witnesses. (R6-193). State law

requires the absentee ballot to be malled, or personally

del.lvered by the voter. (R6-186).

Several questlons of Alabama electlon law on absentee voting

were raised by the evidence in this case: (i) whether Alabama law

prohiblts another person from actually filllng out an absentee

16

ballot and affidavit, or slgnlng the baJ.lot and affldavit with a

voterrs consent, but outslde the voterrs presence; and (il)

whether a witness to the affldavlt on the face of the mailing

envelope must actually see the'voter slgn hls affldavlt, or must

requlre the voter to attest his signature and other lnformatlon

on the envelope.

D. Thc Evldcnce Fregentad At Trlal'

The Government made no claim, and lntroduced no evldence, to

demonstrate that any of the alleged absentee ballots at lssue

here were voted by a person who was reglstered to vote, or who

had voted, ln another county, or who was not otherwlse quallfled

under Alabama law to vote an absentee ball.ot in Greene County.

(R14-45 , 47-481. The thrust of the Governnent claim on the

counts relevant to thls appeal was that Mr. Gordon had

partlcipated as a wltness to affidavits on two maillng

envelopes ln a practice, termed "proxy voting,"6 v. Turner,

Hogue ander whlch, whlle wldespread in Greene County, T $ra,s

6 ,,Proxy votlng, " a term colned by The Honorabl.e Emmet R.

Cox, United States Dlstrict Judge for the Southern District of

AJ.abama durlng a related prosecutlon, Unlted States v. Turner,

Hoque and Turner, Clv. No. 85-OOO14 (S.D. AIa. July 5, 1985)(Jury

verdict of acqulttal) lnvolves the authorlzation glven by a voter

to another person to mark the ballot or, with the voterrs

permlssion, to sign the voterrs name to the balLot affldavlt.

Judge Cox charged the Jury in Turner that marklng a ballot wlth

the consent of the voter was legal and constitutionally protected

activity. Mr. Gordon furnlshed the Distrlct Court in this case

wlth a copy of Judge Cox's instruction, but the Court determined,

contrary to Judge Cox, that proxy voting was illegal. ln Alabama.

( Rl5-25-2s ) .

7 In its remarks followlng lts presentence report, a United

States Probatlon Offlcer noted that the "U.S. Probation Office

agrees that there existed the practlce of 'Proxy r,'otlng' ln

Greene County. The Court may wlsh to conslder this as a

mitigating factor." (R1-78-5). This practlce was conflrmed by

testlmony at trial . ( R13-52-53, 62 , 74-75) .

t7

lllegal under Alabama law. Mr. Gordonrs evldence tended to show

that Al.abama law on proxY voting was not codifled (R12-145), had

not been interpreted by the Alabana courts, (id.) and was unclear

even to experts on Alabama election Iaw. (R12-143). No evidence

was proffered that Mr. Gordon knew that Alabama law prohiblted

"proxy votlng. "8

Mr. Gordon also contended that absentee balloting was

crltical to the ability of blacks in Greene County to participate

1n elections, since large numberE of the county's citizens worked

in Birnringhan or Tuscaloosa, or etere otherwlse absent from the

county between 8:00 a.m. and 6:OO p.n. when the polls were open.

(R12-152). fn addltlon, many elderly and illlterate blacks,

proud of thelr "votlng rights" and ellglble to vote absentee,

could not do so wlthout aEsistance from persons Ilke Mr. Gordon.

(R13-37-56).

The twenty-one counts subnltted to the jury lnvolved a total

of eleven ballots five cast by elderly residents of the Greene

County Nurslng Hope, four cast by relatlves on behalf of other

relatives, and the two on which convlctions were ultimately

obtalned.

With respect to the ballots cast by residents of the Greene

County Nursing Home, the Government contended that, olthough each

balLot was fiLled out in the presence of the proper voter, none

of whom had been adjudged lncompetent, the voters no longer

I An Attorney General oplnion issued July 13, 1984, in

responae to a query from the Secretary of State, announced that

the ballot affldavit may not be executed by a third party who had

been given power of attorney by telephone. Thls opinion was

unknown to any of the experts who testlfled on Alabama election

Law, (R12-144, 145-6) and was not disseminated to the public by

the Greene County Absentee Election Manager. (R?-37).

18

possessed the mentaL competency to vote. The Government further

alleged that, 3s wltnesses to the casting of each baIlot, Mr.

Gordon and Mr. Daniels "knew these people werenlt competent to

vote."9 The'Jury acquitted both defendants of all charges based

on these ballots.

Three other absentee ballots lnvolved clalms of 111egal

,,proxy votlng'r: Mr. Gordon served as a wltness for a SiSter who

voted for her brother, a girlfriend who voted for her boyfrlend,

and a Reverend who assisted hls cousln (who actually slgned the

affidavit but not ln Mr. Gordon's presence). While acknowledging

the technical impropriety of wltnessing for a thlrd party who was

slgnlng for a voter, MB. Gordon presented evldence, as lndlcated

above, that thls was a common practice in Greene County, and that

there was a legltlnate basls for bellevlng each of the third

parties had the express consent of the voter to sign the ballot.

Mr. Gordonrs proof indicated that he did not lntend to defraud

the electorate, but instead intended to further the absentee

voters' desires to cast votes ln the primary or runoff. Mr.

Gordon malntalned throughout trial that proxY absentee voting was

a legal, common, and wldely tolerated practice in the state and

in Greene County ln Particular. Four expert witnessesl0

9 The suggestlon that a person wltnesslng the slgnature of

the voter on an absentee ballot affidavit has a duty under

Alabama law to ascertain the quallflcations of the voter rrlas

challenged both by defense wltnesses and by Government wltnesses

(the Greene County Absentee Election Manager) (R7-61-62, 7l), Mr.

Gordon's polltical opponents, and the Admlnistrator of Elections

for the State of Alabama. (R13-159-63; R13-772; R12'1471.

10 The wltnesses were: (1) Mary Snoddy, the Circult Clerk

of Green County; (11) Helen Moore, Alabama'S adminlstrator of

elections, as well as a panel member of the Federal Election

Commisslon; (iii) Dr. Robert Brown, a member of the Greene County

Board of Reglstrars; and (lv) Edward Still, General Counsel to

19

testified that a voter may authorLze another person to assist the

voter ln castlng, and ln some lnstances signing, his or her

ballot. (R?-93-94, R12-L29-L3O, Rl3-6L-62, 74-75, R12-L43-L44),

In bdditLon, many Greene County resldents testifled that they had

engaged ln proxy votlng on one or more occasions. (R-12-103, R13-

L72, 183). No evldence was presented that any prohlbition

against proxy voting was codifled or known to Mr. Gordon. lhe

jury acqultted Mr. Gordon of those counts.

The counts on whlch Mr. Gordon waE convicted llnked him to

absentee ball.ots cast in the names of Nebraska and Frankland

Underwood, two uncles of his wife. Mr. Gordon acknowledged that

he slgned the malling envelopes on these ball.ots aa a witness.

These ballots were wltneseed by Mr. Gordon during a fanily

reunlon held at hls wlfe's fanlly home shortly before the

election. A number of family members attended thls reunlon and

ftlled out abeentee ballots at that tlme.

Richard wtlliams, a handwrlting expert employed by the

.Federal Bureau of Investlgatlon, testifled that the witness

signatures $rere in Mr. Gordonrs handwriting, but the voter

signatures on the affidavit envelopes had not been signed by Mr.

Gordon. (R11-52). Although the FBI apparently tested the

bal.Iots chemically for flngerprlnts, the Government lntroduced no

evidence suggesting that Mr. Gordon had ever even touched the

actual absentee ballots enclosed inside the "secrecy envelopes."

(R11-Sg-S4). Although Mr. Wtllians testlfied that Nebraska and

Frankland Underwoods' names on the ballot affldavit and ba]lot

appllcatlon had not been signed by them, rro evidence was

the State Democratic Executlve Committee.

20

lntroduced linking Mr. Gordon to any name on any of the documents

other than hls own.

Frankland Underwood, a self-proclalmed "drinklng man, " had

llttle recollection ln 1985 of events from the precedlng Yearl1

except that he had come back home to Greene County from Brewton

where he presently llves to vislt hls fanlly sonetlne in the

sumner of 1984. (R7-161). He acknowledged that he had been

preoccupied durlng that vlsit, ?8 he apparently often is, with

drinklng and getting a drink.12 (R?-162; R12-?9). He did not

remenber, and $ras not paytng attentlon to, convcrsations during

that vlslt except to the extent they related to drinking. (R7-

L621, He denied, however, giving anyone permisslon to obtain or

vote an absentee ballot to enable hln to particlpate ln the

September 1984 primary. (R7-1?1).

Other family nrembers who were present during his 1984 summer

visit to Greene County, however, teetlfied that they spoke

dlrectly to hin about the upcomlng election. His nlece, Ray

Anthnee Patterson, testifled that she asked hlm whether he wanted

the fanily to asslst hin to vote by absentee ballot in the

prlmary, to which he responded, "He11. Do it like you always do

lt." (R12-?9). His nephew, Macaroy Underwood, confirmed this

conversatlon between Frankland Underwood and his niece. (R7-

11H" speclflcally denled, for example, that he met wlth the

FBI in September 1984 or at any tlme that year. (R7-158-59).

The Government stlpulated that such a meetlng had ln fact taken

place. (R7-159) .

t2 Defense counsel observed for the record that Mr.

Underwood's eyes at trial errere red and tearing and that the smell

of liquor was on hls breath. Mr. Underwood admitted drlnking the

night before, but the judge foreclosed any further inqulry into

the state of his lntoxlcatlon. (R7-149, 151-52, 155).

2t

1O9). Splver Gordon was not present durlng this conversation or

at any tlme durlng Frankland Underwood's vlsit. (R7-162, R13-

L23-41 .

The trlal Judge permitted the deposltion of, the other unc1e,

Nebraska Underwood, to be read to the Jury in lleu of ln-person

testlmony. (R1O-202). According to hls deposltlon, Nebraska

Underwood has nu.Ltiple sclerosis, tires easily and concededly has

problems rememberlng things. (R1O-212-213, R12-t2t-221. Also

accordlng to hls deposltion, lt $ras only after the prlnary that

he learned that an absentee ballot had been voted ln hls name.

Various famlly members, however, recalled a trlp to Greene

County by Nebraska Underwood in the summer of 1984, a trip whlch

Nebraska Underwood also recalled, during whlch he consented to

have an abeentee batl.ot voted in hls name ln the prlmary.

Oderrle Underwood, Nebraska Underwoodrs nephew, recalled that he

spoke with Nebraska Underwood about the primary and the

candidates during the visit, and that Nebraska Underwood stated

that he wished for Mr. Gordon to handLe hls absentee bal.lot.

(R13-12O). His slster-in-law, Mattle Underwood, also recalled

this conversatlon. (R1 2-46-48, 7g ) .13

It was a greneral fanily practlce for absent members of the

Underwood famlly to vote by absentee ba]lot. (R13-106, 114).

13 Mr. Gordon was not present for this conversatlon and

did not engineer lt. (Id.) Mattie Underwood te5tified that

after hearing thls converaatlon between her son and Nebraska

Underwood, she telephoned her daughter, Ms. Gordon, and told her

of Nebraska Underwood's intentlon to vote an absentee balIot.

(R12-56). Mrs. Underwood testlfled that she could not recall who

then prepared the applicatlon for an abEentee ballot in the name

of Nebraska Underwood. (R12-55). Mr. Gordon was not present

during any famlly conversatlons, ho$rever, about the absentee

ballots of Nebraska and Frankland Underwood. (R72-47-48,'19, R13-

L23-24) .

22

Family gatherlngs were held by Mattie Underwood at her home prlor

to electlons. There, family members wouLd gather to dlscuss and

decide how they would be voting ln the upcoming election. (R13-

1O3-O9). After comlng to a declsion, ?D absentee ballot for each

member of the famlly who wanted to vote but woul.d not be able to

go to the polls wouJ.d be marked, and the affldavit on the maillng

envelope wouJ.d be completed. ( Id. ) Such gatheri.ngs were

important to Mattie Underwood ln partlcul.ar because of the 'rvery

hard tlme" she and her family had experienced ln reglstering to

vote ln earlier decades. She was determined that her children

would vote ln each eJ.ectlon. (R12-43-44) .

Mattie Underwood and each of her three chlldren testified

that they attended a famtly gatherlng held prlor to the September

4th prlmary. AlI four witnesses testified that absentee baLlots

were prepared in the names of both Nebraska and Frankland

Underwood at that gathering, and that neithcr Nebraska or

Frankl.and Underwood was then present. Mattie Underwood testlfled

that Mr. Gordon arrived at the gathering after the absentee

ballots had been voted. (R12-67-68). MacaroY Underwood

testified that he thought Mr. Gordon arrived after the family had

begun to mark the absentee ballots and signed the absentee

ballots. (R13-103). Mr. Gordon then slgned as a wltness the

mailing envelopes of Nebraska and Frankland Underwood, along with

those of a number of family members who were present.

At the close of the trial, over strenuous defense obJection,

(R15-25-31) the DiEtrict Court instructed the iury that proxy

voting is per se illegal in Al.abama, (R16-26'281 , and that they

could convict if they found that Mr. Gordon had the lntent to

23

violate, or wlth bad purpose had disregarded, €ither federal or

state Law. (R16-4O , 46, 58-60) . The Court aJ.so charged, over

defense obJection (Rl5-3?-4L1, that a wltness to a voterrs

slgnature must observe the voter elther personally sign the

affldavlt or personally acknowledge the slgnature. (R16-27).

The Court refused Mr. Gordon's request to charge the JurY that a

false or forged writlng ls not establlshed merely lf one person

has signed the nane of another and lf there may have been real or

percelved authorization for so signlng. (R15-7e-79). The Court

refused another request by Mr. Gordon to charge -- as Judge Cox

had done three monthe earller that both Constltutlonal and

statutory authorlty exlsts "givllng] . voters the right to

seek assl.stance ln votlng absentee, includlng by allowing someone

else to mark thelr baLlots for them." (R15-79-81)'

Mr. Gordon articulated several reaaons for hls obJection to

the District Courtrs lncorporatlon of Alabama law on proxy votlng

into its instructlons. The law had not been codlfied or

promulgated, was unclear, and contrary practlces were wldespread.

He argued there was no evidence that he had known or had reason

to know that this was the law. He also requested a charge,'that

was not given, that "a vlolation of Alabama law is not at issue

ln this case." (R15-83).14 He further asked the Court to charge

that his liabillty for witnessing a proxy vote required proof of

a will.ful dlsregard of the law. (R16-54-56) He urged that

t4 Mr. Gordon aJ.so requested a charge that,

notwithstanding reference to Alabama laws, viol.atlon of Alabama

law ln and of ltself does not constitute a violatlon of federal

Iaw. The District Court refused the charge as requested, (R1-

7O-1g1, indicated that it would seek to incorporate the

substance, (R15-83), but then did not. See, €.9., (R1-74-6).

24

unl.ess the District Court's proposed charges $rere modif ied to

state that some difference of opinion exists amongi experts (R15-

g2) and that in September, 1984, there were people wlth "an

honestly different vlew, r' the instructlon would mean then "Your

Honor is instructing them to find the defendant gullty." (Id.)

The lnstructlon on proxy voting was given wlthout modlflcatlon.

E. Tha Dlatrlct Courtrs Modlflcd Allcn

Charge

The Juryrs dellberatlons on the charges against Mr. Gordon

were protracted -- marked by frequent interchangres between the

Distrlct Court and the jury foreman. The Jury lnitlall.y retired

on Thursday, October 10, 1985, 3t L:25 p.n. (R16-71). At 4

o,clock, the foreman sent a wrltten message requesting the

deposition testimony of Nebraska Underwood (R16-74), one of the

Greene County voters Mr. Gordon had been charged wlth defrauding.

The Jury dellberated through the afternoon of October 10th until

6:O5 p.rn. (R16-8?), when the Court pernlttcd the Jurors to rccesg

for the night. (R16-88) .15

The folLowing mornlng, the Jury resumed lts deliberatlons at

9:05 a.m. (R1?-3); adJourning for lunch at 11:45 a.m. (R17-5) and

resuming at tztT p.m. (R17-7). At 3:25 p.n., the Jury sent two

messages to the Court: (i) "9{e have a dlfference in opinion on

the meaning of rplaced & caused to be placed' ln each of the mail

fraud cases," (R1-70-4t; Rl7-tL-12); and (1i) "Would you repeat

your comments on actlng in good faith as opposed to the law. "

15 Although Mr. Gordon had moved at the outset of the trlal

for seguestration of the jury, arguingr that It was "critlcal" in

view of the "substantlal publicity" surrounding the votlng fraud

cases (R1-7O-LOzl, the notion was denied by the District Court.

Through the five days of Jury dellberations, Jurors were

permitted to return to their homes each evening.

25

(Id.) After further instructions on these issues (R17-L2-22),

the Jury retired agaln at 4:10 p.r. (Rt7-221 .

An hour later, the jury sent a messa€te to the Court

lndicating that it had "reached a verdict on one defendant and

cannot cone to a unanimous decislon on the other and would

appreciate the Judge's ruling." (R1-?0-41; R17-23). The Dlstrlct

Court brought ln the Jury and recelved its verdlct on Mr.

Gordon's co-defendant, Frederlck Danj.els, who was acqultted of

aIl charges. (R1-7O-4O; R17-24).

The Court then inquired whether the jurY, durlng lts ten-to-

eleven hours of deliberatlons, had come close to a unanlmous

verdict on the charges against Mr. Gordon. The foreman responded

that the Jury was hopeleealy deadlocked and that further

deliberations would be frultless. (R1?-26-271. The Court

replied, that it would regulre tha Jury to deliberate further,

(Rt7-22-281 , renlndlng the Jurors that lt "ha,s taken almost two

and a half weeks, Et least, for the evidence to be presented" and

stated to the Jurors that lt was "fulJ.y persuaded that additlonal.

del.lberations are in order." (R1?-28). The Court thereupon

dismissed the Jury for the evening and lnformed the lawyers of

his intention to give a modified "A.!!en charge[ to the Jury the

following day. (Rl7-29) .

In a chambers conference the next morning, Saturday, October

12th, counsel for Mr. Gordon unsuccessfu]ly objected to further

Jury deliberations and moved for a mistrial.. (R17-31). The Court

outlined its proposed charge (R1?-32-34) and rejected defense

requests that the jurors be lnformed (i) that "tilt ls not proper

for you to yield or give up a consclentiously held opinion in

26

order to reach a comPromise," (R1?-36); or (ff) "that they do not

have to reach a verdict ln this case. 'r (R17-37).

The Court then brought ln the jury and read its nodified

Allen charge, which ls set forth ln full in the Record Excerpts.

In that charge, the Court stressed, anon€, other polnts, that

,,[t]he tria] has been expenslve in time, ef fort and money to

both the Defense and the Prosecution . Obvlously, another

trlal would only serve to increase the costs to both sides. "

(R17-3s).

At various times during the day on Saturday, defense counsel

renewed lts reguest for a nistrial. (R17-44-45,46,50). At 4:OO

p.m. the Court received word that "[w]e the Jury have come to a

verdict on all but (9) lndictnents. In the (9) indlctments ere

are ln a deadlock." (R1-?O-38; R1?-51). The Court lnvited the

jury to submit its partial verd,ict, whlch acquitted Mr. Gordon of

9 counts agalnst hin. (R1-36-3?; R17-52). After polling the

jury, the Court asked the foreman for the Jury's positlon on the

remalnlng counts; he lnformed the Court that further

deliberatlons would not asslst the Jury to reach a verdict. (R1?-

55-56). The Court then polled each Juror lndlvidualIy. Eight

agreed with the foreman that no further progress $ras Possible.

One juror thought unanlmlty was poseible on one count; another

belleved it possible "on a fe$r. " One Juror stated generally that

furthdr deliberatlons might be useful. (R17-56-60).

The Court declded instead to permlt the Jury to dlsperse

until the following Tuesday morning after the Columbus Day

holiday on Monday, October 14th, (R17-65). The Court rejected a

defense request that the Jury be given the option to reconvene on

27

Sunday rather than on Tuesday. (R17-66-67). The Court then

stated to the jury that it was "not unmlndful of the opinion that

you have expressed to the Court in response to ny ingulry. I

thank you for your oplnlon. But f am the ultlnate declsion-maker

as far as thls partlcular questlon is concerned. And I have

formed an oplnlon that is perhaps dlfferent from many of you. "

(R17-69-70).

When the court reconvened on Tuesday morning, the District

Court, after conmendlng the iury f,or lts progress, g?v€

addltional lnstructlons, urglng them agaln to "be aB leisurely in

your del.lberations as the occasion may require, and take

all the tj.me which you may feel that is neceasary." (R17-75).

The jury deliberated throughout the mornlng and recessed for

Lunch, havlng sent the Court a mesaage that it was "making some

progress." (R1-?O-33; R1?-8O). At 4:O0 p.m., the foreman

lndlcated that the Jurors wished to "break for the day. " (R1-7O-

34; R17-99). Defense counsel strenuously urged the Court to

declare a nlstrlal. at this polnt, notlng that the jury had been

deliberating for nearly 3 L/2 days. (R1?-99-10O). Instead the

Court overruled the obJectlon, (R17-1OO), and ordered the iury to

recess until 9{ednesday, October 16th.

On the 16th, after the JurY resumed lts deliberations, one

of the defense attorneys reported anonymous telephone calls

lnforning counsel that one of the Jurors had been overheard

discussing Jury dellberations at lunch with a non-juror. (R17-

105). Defense counseL also noted that an article in the

l{ednesday, October 16th edition of the Birmingham Post Herald,

reporting on an acquittat the prevlous day in another of the

28

voting fraud cases, quoted the judge in that caae as saylng that

the defendant, "Mrs. Underwood had done very litt1e compared to a

lot of people. I do thlnk that some practices have been taking

place that should iolly-well stop. I take a dj.m vlew of people

cheatlng ln electlons by whatever device. " (R17-XO6). Counsel

moved for a nistrlal, warnlng that "a Juror seeing that

particular language might take that lnto conslderation, glven the

fact that they are not sequestered, and the amount of time that

they've been out. " (R1?-105) . That motion, and Elnllar

motlons 16 that followed later ln the day (see R17-1O9-t2), were

summarlly denied. (R17-1O7, 1ld) .

At L!257 a.m. the Jury sent a message reading, "W€ have come

to a verdict on 9 counts and we also feel that we cannot reach a

verdict on 3 counts. We also f eel that with tnore tlme we will

not be able to reach a verdlct on the last 3 counts." (R1-32;

R1?-118). The Court assembled the Jury and asked whether any

Juror had discussed the case with Jurors outside the Jury room or

wlth any others, or had been subJected to media. coverage of Mr.

Gordonts case or other voting fraud cases. (R17'L2O'2L). None

responded. The Court then received the verdj.cts.

The Jury found Mr. Gordon not guilty of five charges, and

guilty of four counts of nalL fraud and furnishlng fal.se

informatlon with respect to Nebraska Underwood and Frankland

underwood. (R1-?o-4-5; R1?-t241. After polllng the jury, the

Court noted that the gullty verdlcts were starred with the

16 Defense counsel later reported to the court that an

anonymous calter had "indlcated that one of the jurors had told

another person that another Juror was so raclst that [that] had

to be called to that juror's attentlon." (R17-113).

29

undersigned words, "aLl oulltv verdicts with recommendatlon for

gl9ggg5[. " ( R1-?O-45; R1?-13? ) ( emphasis added) . The Court then

instructed the jury that "punishment is a matter within the

excluslve province and prerogatlve of the Court," (R17-138), and

indicated that "1f, ln fact, the verdlct ls conditloned

upon', its recomnendation of clemency, the Court would not accept

the verdlct. (R1?-139). At defense request, the Court then sent

the jury back for further deliberations; shortly afterwards, it

returned to report that the verdlct woul.d stand. (R17-L4t-42).17

Mr. Gordon flled a timely written motlon for Judgnent or

acqulttal on several grounds (R1-73), anong them that the court's

refusal to declare a mlstrial and its Al.len lnstructlons had led

to a compromise verdict. (R1-73-3-4). Counsel subnltted two

newspaper artlcles ln support of the motion in which several

jurors were guoted as adnitting that the prolonged dellberations

and Jury instructions had forced a verdict. The artj.cle

responded that "althougih six Jurors believed Gordon was innocent,

they voted guilty on four counts as a resu.Lt of a compromS.se when

Judge E.B.Haltom refused to declare a mistrial and release them

after they reported they were thopelessly deadlocked.!" (Rl-71-

4). One juror reported that s/he "rwouldn't mind telling him

. to his face he's not guilty."' (Id.) Another stated that

tilf he dld anything, he didnrt do it

lntentionally. the man was busy. 9{e all

said he was a good man. He was in the

nursing home, visiting o1d folks, o11 the

l7 Another po1l of the jury reveaLed unanimous sentlment

that further dellberations would nct resuJ.t in a verdlct on the

additional counts (R17-148-521; the Court then decl.ared a

mistrial on those counts. (Rl7-155). The government subsequently

moved to dismiss those counts with preJudlce (R1-83) and the

District Court granted the motion. (R1-85).

30

tlme. He didn't go ln there iust to steal

thelr votes. He thought they had a rlght to

vote. A nan[J that busy makes nistakes. There

wa6 a reasonable doubt.

(R1-?1-5). The Dlstrlct Court denied Mr. Gordon's request for a

full evldentlary hearlng and overruled the motlon. (R1-75).

III. STANDARDS OF REVIEW

At least four of Mr. Gordonrs claims ralse issues of

federal statutory or constltutional law reguirlng lndependent

revlew by this Court. Those lssues lnclude Mr. Gordonrs cLalms

that: ( 1 ) Batson v. Kentuckv applies to hls case; (il) the

Court should reverse Mr. Gordon's convictlon under its

supervisory powers because of the Governnentrs systenatic

exclusion of black Jurors; ( ilt ) the Distrlct Court

mlsinterpreted and misapplled the mail fraud and votlng rights

statutes; aild (lv) the Dlstrict Court erred ln its incorporatlon

of Alabana election law into the iury instructlons.

Four of Mr. Gordonrs claims requlre this Court

independently to apply federal statutory oi constitutional

standards to record facts. See, e.g., Cuv1er v. Sullivan, 446

U.S. 335, 34L-42 (1980). Those issues include Mr. Gordon's

claims that: (1) the Government's prosecution of hin was, on the

evidence of record, a selective and lnvidious prosecution; (1i)

the Government's systematic exercise of its peremptory challenges

to exclude all black jurors establlshes a prima facie Equal

Protectlon violatlon under Swain v. Alabama and Batson v.

Kentuckv; ( iv) the Government's Justifications for excusing

severaL black Jurors are insufficient under Batson; (v) the

evidence is insufficient to prove each count against Mr. Gordon;

(vl) the District Court's supplemental instructlons to the jury

31

violated thls Courtrs strlct requirements for Al1en charges.

Mr. Gordonrs claim that the Dlstrict Court erred in

denylng his motlons for discovery and for a hearing on selective

prosecutlon is properly reviewed under an abuse of discretlon

standard. Wavte v. United States,

-U.S.-,

84 L.Ed.2d 542, 567

( 1985) (Marshall, J., dissentlng) .

ST'UMARY OF ARGT'UEI{T

The Government achleved 1ts convlctlons against

Appellant Splver Gordon only by systematlc distortlons both of

law and of fact. From the outset, the Governmentts investlgation

into votlng fraud ln AIabaBars Black belt fo1J.owed the selective

and vlndlcative pattern first condemned in Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

1 18 U. S . 356 ( 1886 ) , by singling out only maJority black

counties, and withln those counties at the behest of local.,

primarlly white political rivals only black polltical

actlvists and their supporters. The pattern of indictnents that

resulted from this campaign, as the .Maglstrate found in thls

case, spared even those members of rival politlcal partles who

had committed similar election law violations. Under these facts,

the District Court erred 1n denying Mr. Gordonrs motions for

dlscovery of the Government and for an evidentiary hearing on his

clalm of selectlve prosecution.

At the outset of the trial, the Government, despite

repeated defense obJectlons, exerclsed its slx peremptory

challenges to remove every black venire person from Mr. Gordon's

jury. Those strikes followed a recurrent pattern of exclusions

in the Government's other voting fraud cases against black

polltical leaders. This pattern sufficed to establish a prima

32

facle Egual Protectlon vlolation regulring a full hearing under

Swaln v. A1abama, 38O U.S. 2O2 (1965). Moreover, the pattern in

Mr. Gordonrs case aJ.one meets the relaxed prima facle standards

announced ln Batson v. Kentuckv,

-U.S.-,

90 t.Ed. 2d 69 (1986).

Several of the explanatlons volunteered by the Government for its

strlkes are lnsufflclent as a matter of law, requJ.ring a reversal

of Mr. Gordonrs convictions. Slnce the Dlstrlct Court made no

factual flndlngs on other explanations, which were sharply

controverted by defense proffers, a remand for a further

evidentlary hearlng ls necesaarY, at a minimum.

The Dlstrlct Court's instructions to the trial Jury

improperly incorporated disputed and anblguous provlsions of

Alabama election Iaw lnto its charge to Mr. Gordon's Jury. The