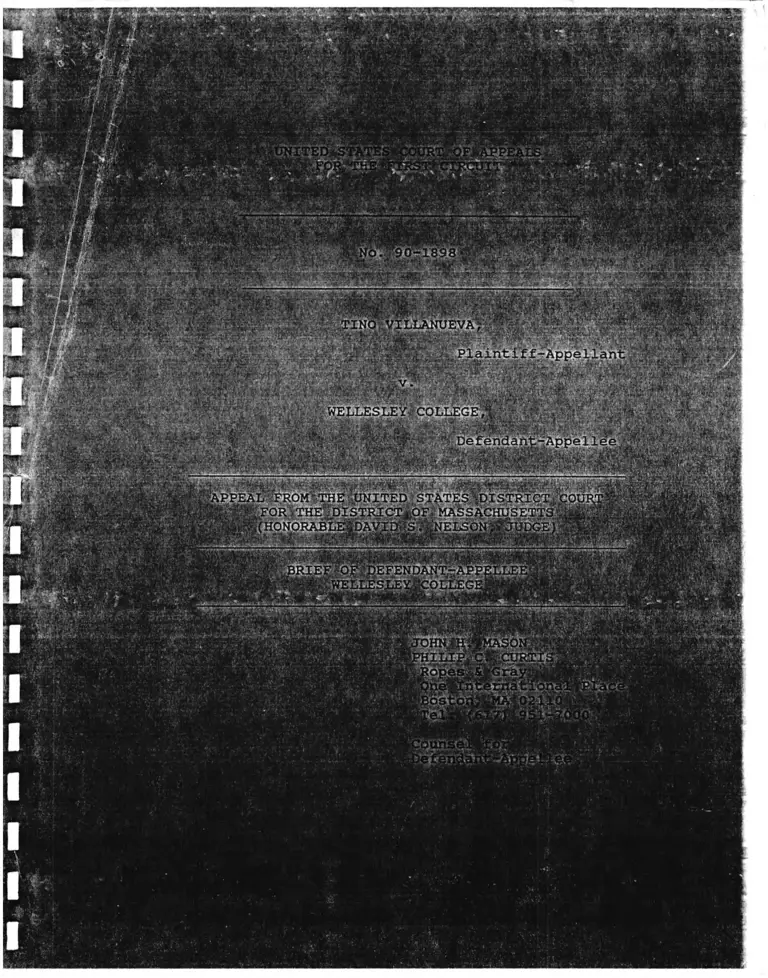

Villanueva v. Wellesley College Brief of Defendant-Appellee

Public Court Documents

December 7, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Villanueva v. Wellesley College Brief of Defendant-Appellee, 1990. 2d12920a-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/950d3ff3-8bac-455a-b748-3eefc5242926/villanueva-v-wellesley-college-brief-of-defendant-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

:■• ■••■■•■ I ' '

j» £ :'<&. '\ fcv v .•■»••

g a B p | p :f ' t-iatsaB’̂ a.w«.î E

RULE 26.1 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Wellesley College is a nonprofit institution of higher

learning organized under the laws of the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts, and as such it has no parent companies,

subsidiaries or affiliates that have issued shares to the publ

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE I S S U E .............................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .............................. 1

STATEMENT OF F A C T S .................................. 3

ARGUMENT ,

I . SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS PROPERLY GRANTED BECAUSE

WELLESLEY ARTICULATED LEGITIMATE,

NONDISCRIMINATORY REASONS FOR DENYING TENURE

TO PLAINTIFF, AND PLAINTIFF FAILED TO SHOW

THAT THOSE REASONS WERE A PRETEXT FOR UNLAWFUL

DISCRIMINATION ............................ 11

A. The District Court Applied Well

Established Principles In Allowing

Wellesley's Motion For Summary Judgment . 18

B. The District Court Correctly Found That

Wellesley Articulated Legitimate,

Nondiscriminatory Reasons For The

Denial of Tenure to Plaintiff ........... 23

C. There Was No Probative Evidence That

The Reasons Wellesley Articulated For The

Denial of Tenure to Plaintiff Were Obviously

Weak Or Implausible Or That Wellesley

Manifestly Applied An Unequal Standard

To Plaintiff's Tenure Application . . . . 27

1. The Tenure Candidacies of Professors

Renjilian-Burgy and Agosin Do Not

Permit A Reasonable Finding of One-

S i d e d n e s s ..................... 30

2. The Only Probative Comparisons Are

to Professors Renjilian-Burgy And

A g o s i n ..........................37

3. Plaintiff's Other Evidence Fails

To Show That The College's

Articulated Reasons Were

Pretextual..................... 41

-1-

II. THERE WAS NO OTHER PROBATIVE EVIDENCE OF

IMPROPER DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PLAINTIFF

BECAUSE OF HIS RACE, COLOR, NATIONAL ORIGIN OR S E X ........................................

III. PLAINTIFF'S CLAIM OF AGE DISCRIMINATION

WAS ALSO PROPERLY D I S M I S S E D ............. 4 8

Conclusion........................................... ...

f

-ii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PageCASES

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby. Inc..

477 U.S. 242 (1986).............................. 19

Banerjee v. Board of Trustees of Smith College. 648

F . 2d 61, 66 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 1 ) ............. 20, 39, 46

Brown v. Trustees of Boston University. 891 F.2d 337,

346 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) ................. 16, 21, 27, 30

Cook County College Teachers Union.

Local 1600 v. Byrd. 456 F.2d 882

(7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 484

(1972), reh. denied. 414 U.S. 883 (1972) . . . . 43

Dance v. Ripley. 776 F.2d 370, 373

(1st Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ................................... 13

Pea v. Look, 810 F.2d 12, 15 (1st Cir. 1987) 13, 22

DeArteaga v. Pall Ultrafine Filtration Corp..

862 F . 2d 940 (1st Cir. 1988) .................... 19

Diminnie v. General Electric Co..

47 BNA Fair Empl. Prac. Cases 245

(W.D.Ky. 1989) 48

Federal Insurance Co. v. Summers’. 403 F.2d 971,

975 (1st Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) .............................. 17

Gray v. New England Telephone & Telegraph

Co. . 792 F. 2d 251, 255 (1st Cir. 1986) ......... 15

Griggs-Rvan v. Smith. 904 F.2d

112 (1st Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) .............................. 21

Hebert v. The Mohawk Rubber Co..

872F.2d 1104,1111 (1st Cir. 1989) 20

-iii-

Jackson v. Harvard University. 721 F. Supp.

1397 (D. Mass. 1989) ............................ ...

Janiqan v. Tavlor. 344 F.2d 781, 784

(1st Cir. 1965), cert. denied. 382 U.S. 879 (1965) 17

Johnson v. Allvn & Bacon. Inc.. 731

F.2d 64, 70 (1st Cir. 1984), cert, denied.

469 U.S. 1018 (1984) ............................ 12

Keyes v. Secretary of Navv. 853 F.2d

1016, 1023 (1st Cir. 1988) ............. 11, 14, 15

Loeb v. Textron. Inc.. 600 F.2d 1003,

1019 (1st Cir. 1979) ............................ 11

McDonnell Douglas Coro, v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 , 802 (1973)..................... 11, 12

McGruder v. Necaise. 733 F.2d

1146 (5th Cir. 1984) ............................ 48

Medina-Munoz v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.. 896 F.2d

5, 9 (1st Cir. 1 9 9 0 ) ............. 13, 14, 15, 21, 38

Menard v. First Security Services Coro..

848 F.2d 281 (1st Cir. 1988) ............... 15, 20

Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. v . Ditmore.

729 F . 2d 1 (1st Cir. 1987) ..................... 19

Oliver v. Digital Equipment Corp., 846 F.2d 103, 107

(1st Cir. 1 9 8 8 ) .............................. 12, 19

Perez de la Cruz v . Crowley Towing and

Transp. Co.. 807 F.2d 1084 (1st Cir. 1986), cert.

denied. 481 U.S. 1050 (1987) ................... 19

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. 109 S.Ct.

1775, 1797 (1989)................................ 11

Rossy v. Roche Products. Inc.. 880 F.2d

621, 625 (1st Cir. 1989) ........................ 16

-iv-

11

Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of

Keene State College. 604 F.2d 106, 108

(1st Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444

U.S. 1045 (1980) ..........................

Texas Dep't of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248, 256 (1980) ........................ 13

The Dartmouth Review v. Dartmouth College.

889 F. 2d 13 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) ...................... 22

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Antonio.

109 S.Ct. 2115, 2122 (1989)...................... 44

White v. Vathallv. 732 F.2d 1037, 1043

(1st Cir.), cert. denied. 469 U.S. 133 (1984) . . 13

-v-

STATUTES

29 U.S.C. § 631(d) 7

Act of October 31, 1986,

Public Law 99-592, § 6 ( b ) .......................... 7

Age Discrimination in Employment Act,

29 U.S.C. § 6 2 1 ............................ 1, 7, 48

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 . . . . 1

M.G.L. c. 15IB, § 4(17) (c) 1

M.G.L. c. 15IB, §4(1) (A) and (B) 7

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 20 00e-l................................. 1

RULES AND REGULATIONS

Rule 3(a) of the Rules for United States

Magistrates in the United States District

Court for the District of Massachusetts...........2

Rule 56(c) of the Federal Rules

of Civil P r o c e d u r e ..............................18

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Handbook of Labor Statistics published by the U.S.

Department of Labor (Bulletin 2217 - June, 1985) 45

-vi-

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

Did the District Court properly grant summary judgment

dismissing plaintiff's amended complaint alleging that

Wellesley College denied him tenure because of his race,

color, national origin, sex and age?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiff-appellant Tino Villanueva (hereinafter

referred to as "plaintiff") was denied tenure in the

Department of Spanish of defendant-appellee Wellesley

College ("Wellesley" or the "College") in December, 1985.

He brought this action in August, 1987, alleging in an

amended complaint that the tenure denial was based on his

race, color, national origin, sex and age in violation of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-l et seq. ("Title VII"), the Civil Rights Act of

1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, the Age Discrimination in Employment

Act, 29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq. (the "ADEA"), and Massachusetts

General Laws Chapter 151B, § 4(1)(A) and (B).

The parties engaged in discovery throughout the period

from August, 1987 through February, 1989. Thereafter, on

March 13, 1989, Wellesley filed a motion for summary

judgment dismissing plaintiff's claim of age discrimination,

and on December 7, 1989, a further motion for summary

judgment dismissing plaintiff's claims of race, color,

national origin and sex discrimination. In support of its

motions, Wellesley submitted a Statement of Material

Undisputed Facts together with supporting affidavits from

Ruth Anne Nuwayser, who is Manager of the Faculty Records

Office at Wellesley, and portions of the deposition

transcripts of various persons who had participated in the

consideration of plaintiff's case.1

Plaintiff filed an opposition to Wellesley's motions,

together with a Statement of Material Disputed Facts and

various supporting exhibits. Thereafter, pursuant to Rule

3(a) of the Rules for United States Magistrates in the

United States District Court for the District of

Massachusetts, the Court referred the matter to Magistrate

Lawrence P. Cohen for recommended disposition.

On June 14, 1990, the Magistrate submitted a report

recommending allowance of Wellesley's motions. After

summarizing the facts shown by the parties' submissions and

the applicable legal principles, the Magistrate assumed that

plaintiff had established a prima facie case of

discriminatory denial of tenure, but found that he had

failed to produce "sufficient evidence by which a rational

1 These portions of deposition transcripts were submitted

as attachments to the affidavit of John H. Mason, counsel

for Wellesley.

-2-

trier of fact — short of mere speculation or conjecture —

could reasonably conclude that the legitimate, non-

discriminatory reason advanced by Wellesley for denying

[plaintiff's] tenure bid was a pretext for illegal

discrimination." (App. Ilia).2

Plaintiff filed objections to the Magistrate's Report

on June 29, 1990. On August 17, 1990, the Court overruled

plaintiff's objections and entered an Order allowing

Wellesley's motions for summary judgment for the reasons set

forth in the Magistrate's report.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The Statement of Material Undisputed Facts which

Wellesley submitted in support of its motions for summary

judgment is set forth in full in the Joint Appendix at pages

16a-55a. In the interest of brevity, that statement will

not be repeated here, except in the following summary form

which will include citations to the Appendix where the

statement is set out, or to other parts of the record where

the events are described in more detail.

Record references are as follows: "App." refers to the

Joint Appendix; "Nuywaser Supp. Aff." refers to the

Supplemental Affidavit of Ruth Anne Nuwayser; "Exh." refers

to an exhibit? and "Dep." refers to a deposition transcript.

-3-

Plaintiff is a citizen of the United States who was

born in 1941 in Texas of U.S.-born parents (App. 20a). From

September 1974 until June 1987, plaintiff was employed in

the Department of Spanish at Wellesley, first as a part-

time Lecturer and then, starting in 1980, as a full-time

Lecturer/Assistant Professor teaching, among other things,

courses in Spanish language and Spanish and Chicano

literature (App. 20a-21a).

Plaintiff was considered for tenure at Wellesley in

academic year 1985-86 (App. 27a). In accordance with the

procedures that were then in effect,3 the members of the

Spanish Department Reappointments and Promotions Committee

(the "R&P Committee") visited one or more of plaintiff's

classes and reviewed, among other materials, all the written

work that plaintiff had submitted as evidence of his

scholarship, as well as letters from three outside

The process of evaluation for tenure was contained in

the Wellesley College Articles of Government, Article IX,

Section 6, attached as Exhibit A to Wellesley's memorandum

in support of its motion for summary judgment dismissing

plaintiff's claims of race, color, national origin and sex

discrimination (and as Exhibit B to Wellesley's prior

memorandum in support of its motion for summary judgment

dismissing plaintiff's age discrimination claims). This

faculty legislation provided, among other things, that the

College would evaluate tenure candidates according to the

factors of (i) quality of teaching; (ii) evidence of

scholarly strength and growth; (iii) relation to

departmental structure; (iv) service to the College in

achieving its educational goals; and (v) external

professional activities.

-4-

evaluators regarding that work (App. 27a-34a). They then

met and considered whether they should recommend plaintiff

for tenure to the College's Committee on Faculty

Appointments (the "CFA") (App. 34a).

In accordance with established practice, the R&P

Committee consisted of the tenured members of the Spanish

Department: Professors Elena Gascon-Vera, Lorraine Roses,

Joy Renjilian-Burgy and Gabriel Lovett (App. 98a).

Professors Gascon-Vera, Roses and Renjilian-Burgy were of

the view that plaintiff should not be recommended for

tenure, while Professor Lovett believed that he should be

recommended for tenure (App. 35a, 36a).

On October 25, 1985, the three-member majority of the

R&P Committee sent a memorandum to the CFA explaining the

reasons for their recommendation against tenure for

plaintiff (App. 36a; Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 34). The

majority explained that:

"As a small department at a small college, it

is imperative for us to secure a colleague who is

outstanding as a teacher, as a scholar, as a

member of the Department and as a generator of new

ideas and resources . . . ."

The majority further explained that, in their view,

plaintiff did not meet this standard either in his teaching

or in his scholarship. More specifically, the majority

stated that the pace of plaintiff's teaching was too slow,

-5-

the students in his classes tended to be passive rather than

active, and plaintiff had not shown in his scholarship that

he was current on the latest trends of literary criticism.

The majority also stated that, while plaintiff had complied

with requests from his colleagues, he had not taken the

initiative either to promote Department activities or to

handle major Department responsibilities. Finally, with

respect to Department structure, the majority stated:

"Due to the size of the department and its

structure (three tenured members are due to retire

in 2007, 2008 and 2009, with Tino slated also for

2007) to tenure Tino would mean that we would all

leave almost at the same time. If we were a large

university department it is more likely that there

would be a slot for Tino, since he brings

strengths as a poet and as an expert in Chicano

culture. We also have to keep in mind that the

next tenureable member would retire in 2020, is

also an internationally known poet with four books

of poetry, more than 30 scholarly articles and two

books of criticism on Maria Luisa Bombal and Pablo

Neruda. Also, this same member has superior

student evaluations, particularly in literature."

At the time the majority of the R&P Committee prepared

this letter, the College had in effect a lawful policy

requiring all tenured faculty members to retire at age 70

(App. 106a).4

In the fall of 1985, the ADEA and M.G.L. c. 151B

expressly permitted colleges and universities to require

tenured faculty to retire at age 70. 29 U.S.C. § 631(d);

M.G.L. c. 15IB, § 4(17) (c). The federal provision was

repealed in October, 1986 - one year after the Villanueva

tenure decision. See Act of October 31, 1986, Public Law

99-592, § 6 (b) (repealing 29 U.S.C. § 631(d) as of December

-6-

I

i

I

I

I

The CFA considered plaintiff's case in November and

December, 1985 (App. 39a-43a). The CFA consists of eight

members, five of whom are tenured faculty members elected by

the faculty at large (Wellesley College Articles of

Government, Article V, Section 9). The sixth member of the

CFA is a black tenured faculty member, selected by the black

faculty at the College (id.). The other members of the CFA

are the Dean and the President of the College, ex officio

(id.). The CFA considers the opinion of the Department R&p

Committee, but CFA members make their own, independent

tenure recommendation to the College's Board of Trustees and

to the President (Defendant's Response to Plaintiff's

Interrogatories No. 4, 22).

During the course of the consideration of plaintiff's

case, the CFA met with members of the R&P Committee on

December 9, 1985 and again on December 11, 1985, and

discussed the case with them (App. 40a, 42a). During these

meetings, members of the R&P Committee majority repeated

many of the concerns they had expressed in their letter and

also stated, in response to questions from the CFA, that

another member of the Department who was due to be

31, 1993). Because the College can no longer be certain

that a tenured professor will retire no later than age 70,

it has ceased to take projected retirement dates into

account in evaluating the factor of department structure.

-7-

considered for tenure the following year, Marjorie Agosin,

was quite strong and that they were concerned, in light of

the number of people in the Department who were already

tenured, that an award of tenure to plaintiff might

adversely affect an award to Ms. Agosin (App. 40a-42a).

On December 13, 1985, plaintiff was notified by letter

from the President of the College, Nanerl 0. Keohane, that

the CFA had voted to accept the recommendation of the

Spanish Department R&P Committee that he not be granted

tenure at the College (App. 43a; Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh.

46) . The letter further stated that, as a result of the

Committee's action, plaintiff's appointment at the College

would terminate at the end of the 1986-87 academic year

(id.) .

Subsequently, on December 23, 1985, Maud H. Chaplin,

the Dean of the College, and Edward A. Stettner, the

Associate Dean, met with plaintiff at his request to discuss

the negative tenure decision (App. 43a). Promptly

thereafter, Deans Chaplin and Stettner furnished plaintiff

with a letter summarizing that discussion (App. 44a;

Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 46). The letter explained that in

reaching its decision, the CFA had determined that

plaintiff's teaching was "much more than adequate, but it

was not outstanding," and further that, as stated by the

-8-

majority of the R&P Committee, plaintiff's written work did

not show that he was current in the latest trends of

literary criticism (id.).

In response to plaintiff's request, the CFA met with

plaintiff and then reconsidered its decision in April, 1986,

but voted not to reverse its prior recommendation that

plaintiff not be granted tenure (App. 43a, 46a-47a). On or

about May 9, 1986, plaintiff filed charges with the federal

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (the "EEOC") and the

Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (the "MCAD")

alleging that he was denied tenure at Wellesley because of

his race, color, sex and age (App. 47a). After conducting

an investigation, the EEOC on May 28, 1987, issued a

determination that there was no probable cause to believe

plaintiff's allegations of discrimination (id.; Nuwayser

Supp. Aff. Exh. 55). The MCAD accorded substantial weight

to the determination of the EEOC and on June 10, 1987

entered its own finding of lack of probable cause (Nuwayser

Supp. Aff. Exh. 55).

Thereafter, on August 11, 1987, plaintiff commenced the

present action. During discovery, plaintiff took the

depositions of numerous persons who had participated in the

consideration of his case, but none of them supported his

allegations of discrimination. To the contrary, even

-9-

Professor Gabriel ("Harry") Lovett, who had vigorously

supported plaintiff for tenure as a member of the R&P

Committee, testified that, in his view, the majority members

of the R&P Committee had substantial and legitimate

reservations about plaintiff's work and did not discriminate

on the basis of plaintiff's sex (Lovett Dep. 79-80).

Similarly, Professor David Ferry, who supported plaintiff

for tenure as a member of the CFA, testified that, in his

view, plaintiff's tenure case was only "borderline" and that

he understood entirely "the reasonableness of the decision

of the majority. . ." (Ferry Dep. 56). Neither Professor

Ferry, nor Professor Lovett, nor anyone else whom plaintiff

deposed, in any sense suggested that any kind of

impermissible discrimination was involved in the College's

decision not to grant tenure to plaintiff.

-10-

ARGUMENT

I. SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS PROPERLY GRANTED BECAUSE WELLESLEY

ARTICULATED LEGITIMATE, NONDISCRIMINATORY REASONS FOR

DENYING TENURE TO PLAINTIFF, AND PLAINTIFF FAILED TO

SHOW THAT THOSE REASONS WERE A PRETEXT FOR UNLAWFUL DISCRIMINATION________________

The burdens of proof in cases of employment

discrimination are well settled. Plaintiff bears the burden

of proof throughout the proceedings, and he must show by a

preponderance of the evidence that some protected

characteristic (here sex, race, national origin or age) was

t-h.Q determinative factor in the defendant's decisions

regarding him. See Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. 109 S.Ct.

1775, 1797 (1989) (where plaintiff has not proven any mixed

motive, Title VII requires "but-for" causation); Keyes v.

Secret a rY_.of Navy, 853 F.2d 1016, 1023 (1st Cir. 1988); Loeb

v. Textron. Inc.. 600 F.2d 1003, 1019 (1st Cir. 1979).

Plaintiff first must establish a prima facie case of

unlawful discrimination by proving sufficient facts which,

standing alone, permit an inference of such discrimination

against him. McDonnell Douglas Corn, v. Green, 411 U.S.

792, 802 (1973); Sweeney v. Board of Trustees of Keene State

College, 604 F.2d 106, 108 (1st Cir. 1979), cert, denied.

444 U.S. 1045 (1980).

-11-

If plaintiff establishes a prima facie case, the burden

then shifts to the defendant to articulate legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reasons for its decision. see

McDonnell-Douglas v. Green. 411 U.S. 792, 802 (1973); Oliver

v - Digital Equipment Corp.. 846 F.2d 103, 107 (1st Cir.

1988). This Circuit has explained the employer's burden in

the following way:

"The defendant's burden to articulate a legitimate

reason is not a burden to persuade the court that he

was in fact motivated by that reason and not by a

discriminatory one. Rather, it is a burden of

production — i.e.. a burden to articulate or state a

valid reason. . . . The defendant can accomplish this

by introducing admissible evidence which would allow

the trier of facts rationally to conclude that the

employment decision had not been motivated by a

discriminatory animus."

Johnson v. Allyn & Bacon. Inc.. 731 F.2d 64, 70 (1st Cir.

1984), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1018 (1984)(citations omitted,

emphasis original).

The Court below found, and plaintiff does not seriously

dispute, that Wellesley articulated legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reasons for its denial of tenure to

plaintiff. Any inference of discrimination thus dissolves,

and the burden of persuasion created by the prima facie case

shifts back to plaintiff to prove that the proffered reasons

for the defendant's decision were not the true reasons —

but were instead merely a "pretext" for unlawful

discrimination. See Texas Pep't of Community Affairs v.

-12-

Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 256 (1980); Medina-Munoz v . R .J .

Reynolds Tobacco Co.. 896 F.2d 5, 9 (1st Cir. 1990)

(inference raised by plaintiff's prima facie case vanishes

when employer articulates its legitimate reasons); Dance v.

Ri.pley , 776 F.2d 370, 373 (1st Cir. 1985).

Plaintiff cannot prove pretext — and thereby revive

the inference of discrimination previously dispelled by

defendant's articulated business reasons — by challenging

the actual merit of the reasons.

"Merely casting doubt on the employer's articulated

reasons does not suffice to meet the plaintiff's burden

of demonstrating intent, for the defendant need not

persuade the court that it was actually motivated by

the proffered reasons in the first place. To hold

otherwise would impose an almost impossible burden of

proving absence of discriminatory motive."

Dea v. Look, 810 F.2d 12, 15 (1st Cir. 1987) (quoting White

v. Vathally, 732 F.2d 1037, 1043 (1st Cir. 1984), cert.

denied, 469 U.S. 133 (1984)). Rather, plaintiff bears the

burden of proving that the defendant's decision concerning

his employment was the product of impermissible

discrimination. As this Court stated in Medina—Munoz v.

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.. 896 F.2d 5, 9 (1st Cir. 1990),

plaintiff

"must do more than simply refute or cast doubt on the

company's rationale for the adverse action. The

plaintiff must also show a discriminatory animus based on age."

-13-

If plaintiff does not show such a discriminatory animus,

summary judgment or a directed verdict is mandated.

In sum, once Wellesley has articulated its legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reasons for denying plaintiff tenure, it

devolves upon him to prove by a preponderence of the

evidence, unassisted by the original presumption of his

prima facie case, that Wellesley's reasons "were not its

true reasons, but were a pretext for discrimination." Texas

Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine. 248 U.S. 248, 253

(1981) (emphasis added); accord. Medina-Munoz v. R,j.

Reynolds Tobacco Co.. 896 F.2d at 9.

Plaintiff's brief on appeal utterly misapprehends his

burden of demonstrating pretext. The reasons given for an

employment decision may not be considered pretexts for

unlawful discrimination even if it is shown that the

decision was misguided, incorrect, or different from the one

that a court or jury might have made. "Errors in judgment

are not the stuff of Title VII transgressions — so long as

the mistakes are not a coverup for invidious

discrimination." Keyes v. Secretary of Navv. 853 F.2d 1016,

1026 (1st Cir. 1988). As the First Circuit has repeatedly

made clear in discrimination cases, "[i]t is not enough to

show that the employer made an unwise business decision

. . . . [or] that the employer acted arbitrarily or with ill

-14-

will." Gray v. New England Telephone & Telegraph Co.. 792

F.2d 251, 255 (1st Cir. 1986). Wellesley was entitled to

deny plaintiff's tenure application for any reasons it

believed, in its sole discretion, were consistent with the

College's Articles of Government, provided such reasons were

not pretexts aimed at masking unlawful discrimination. As

this Court stated in Medina-Munoz.

"[Plaintiff] argues that he put forward enough evidence

to create a litigable question as to whether the stated

reasons were a ruse. If that is so, it is only half

the battle; the other half was lost for he offered no

colorable evidence to show that the reasons, if

pretextual, were pretexts for age discrimination."

896 F .2d at 9 (emphasis original). Accord Keyes. 853 F.2d

at 1026; Menard v. First Security Services. Inc.. 848 F.2d

281, 287 (1st Cir. 1988).

Plaintiff's effort to turn this discrimination lawsuit

into an occasion for revisiting the underlying merits of his

tenure review completely misperceives the foregoing well

established principles. "Neither the defendant's managerial

judgment nor [its] recruiting acumen is on trial in this

case." Keyes v. Secretary of Navv. 853 F.2d 1016, 1026 (1st

Cir. 1988). The mission for this Court is to determine

whether plaintiff has offered sufficient evidence for a jury

to conclude on the basis of that evidence - and not on mere

speculation or conjecture - that sex, race, national origin

-15-

or age discrimination were the real reasons for Wellesley's

actions toward him. As this Court held recently:

"Our role is not to second-guess the business decisions

of an emplyer, imposing our subjective judgments of

which person would best fulfill the responsibilities of

a certain job. While an employer's judgment or course

of action may seem poor or erroneous to outsiders, the

relevant question is simply whether the given reason

was a pretext for illegal discrimination."

Rossv v. Roche Products. Inc.. 880 F.2d 621, 625 (1st Cir.

1989) (citations omitted).

Thus, plaintiff cannot show that the College's reasons

were a pretext for unlawful discrimination by presenting

evidence from which a factfinder might conclude that the

tenure decision could have gone either way, nor can

plaintiff show such pretext simply by persuading the

factfinder that it would have granted tenure to plaintiff.

Rather, plaintiff must show that the College's articulated

reasons for denying him tenure were "obviously weak or

implausible", or that the tenure standards for prevailing at

the tenure decision were "manifestly unequally applied".

Brown v. Trustees of Boston University. 891 F.2d 337, 346

(1st Cir. 1989). As emphasized by this Court in Brown.

"The essential words here are 'obviously' and

'manifestly.' A court may not simply substitute its

own views concerning the plaintiff's qualifications for

those of the properly instituted authorities; the

evidence must be of such strength and quality as to

permit a reasonable finding that the denial of tenure

was 'obviously' or 'manifestly' unsupported."

-16-

Id. at 346. Likewise, a jury may not simply substitute its

own views for those of the College. Accordingly, Wellesley

is entitled to summary judgment unless plaintiff makes a

showing of the strength and quality demanded by this Court

in Brown.

Plaintiff's contention (Brief of Appellant at 46,

n. 37) that he may meet his burden to establish pretext on

the hypothesis that the jury might choose to disbelieve the

defendant's witnesses and explanations is entirely without

merit. See Janigan v. Taylor. 344 F.2d 781, 784 (1st Cir.

1965), cert. denied. 382 U.S. 879 (1965) ("[H]owever

satisfied a court may be from the witness's demeanor or his

demonstrated untruthfulness in other respects that certain

testimony is false, it cannot use such disbelief alone to

support a finding that the opposite was fact"); Federal

Insurance Co. v. Summers. 403 F.2d 971, 975 (1st Cir. 1968)

(party bearing burden of proof does not have right to get to

the jury when the only evidence is testimony against him).

Were this view of the law correct, summary judgment motions

could never be granted in discrimination cases once a prima

facie had been made out — a result clearly contrary to the

explicit holdings of the Supreme Court in McDonnell-Douglas

and Burdine. and of this Court in virtually every one of its

employment discrimination decisions, including Oliver v.

-17-

Digital. Johnson v. Allvn & Bacon. Loeb v. Textron and

Medina-Munoz v. R.J. Reynolds. Further, if the trier of

fact's disbelief of a defendant's articulated business

reasons can, without more, suffice to give rise to an

inference of discrimination, then in reality a defendant

must not only articulate its reasons, it must prove them.

Again, such an interpretation of the law stands in direct

conflict with virtually every discrimination decision handed

down since McDonnell-Douglas v. Green.

Plaintiff's lawsuit was dismissed because he fell "far

short in mustering sufficient evidence by which a rational

trier of [fact] -- short of mere speculation or

conjecture — could reasonably conclude that the legitimate,

non-discriminatory, reason advanced by Wellesley for denying

his tenure bid was a pretext for illegal discrimination."

(App. Ilia). The Court below applied the proper standards

in reaching this judgment. Its decision should be upheld.

A. The District Court Applied Well

Established Principles In Allowing

Wellesley's Motion For Summary Judgment

Rule 56(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

provides that summary judgment shall be granted "if the

pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and

admissions on file, together with the affidavits, if any,

show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact

-18-

and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a

matter of law." As this Court has repeatedly recognized,

summary judgment is appropriately granted under this Rule if

there is "an absence^of evidence supporting the non-moving

party's case." E.g. , Oliver v. Digital Equipment Coro.. 846

F •2d 103, 105 (1st Cir. 1988); Metropolitan Life Insurance

Co. v. Ditmore. 729 F.2d 1, 4 (1st Cir. 1987).

This Court has further explained that the issue is "not

whether there is literally no evidence favoring the non

movant, but whether there is any upon which a jury could

properly proceed to find a verdict in that party's favor."

DeArteaga v. Pall Ultrafine Filtration Coro.. 862 F.2d 940,

941 (1st Cir. 1988). The non-moving party may not rely on

"unsupported allegations and speculations," Oliver v.

Digital Equipment Corp.. supra. 846 F.2d at 109-110, or on

"the gossamer threads of whimsy, speculation and

conjecture." Perez De La Cruz v. Crowley Towing and Transp,

Co., 807 F.2d 1084, 1086 (1st Cir. 1986), cert, denied. 481

U.S. 1050 (1987). Rather he must produce evidence that is

admissible and significantly probative of the claims he has

made. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.. 477 U.S. 242, 249-

250 (1986). Otherwise, no genuine issue of material fact is

presented and summary judgment is properly granted. See

also Hebert v. The Mohawk Rubber Co.. 872 F.2d 1104, 1111

-19-

(1st Cir. 1989); Menard v. First Security Services Corp.f

848 F .2d 281, 284-85 (1st Cir. 1988).

The Magistrate explicitly recognized and applied the

appropriate legal standards in this case. Thus, following*

this Court's decision in Baneriee v. Board of Trustees of

Smith College. 648 F.2d 61 (1st Cir. 1981), the Magistrate

assumed that plaintiff had established a prima facie case of

discriminatory denial of tenure5 and considered whether

Wellesley had articulated a legitimate, nondiscriminatory

reason for its action. Concluding that the College had met

this burden, the Magistrate went on to consider whether

plaintiff had produced "sufficient evidence by which a

rational trier of fact - short of mere speculation or

conjecture - could reasonably conclude that the legitimate,

non-discriminatory reason advanced by Wellesley for denying

his tenure bid was a pretext for illegal discrimination."

(App. 111a). Quoting from this Court's decision in Brown v.

Trustees of Boston University. 891 F.2d 337, 346 (1st Cir.

In Baneriee. the Court held that a plaintiff could

establish such a prima facie case by showing that: (1) he

is a member of a protected minority group; (2) his

qualifications for tenure were sufficiently strong to place

him in the middle group of tenure candidates as to whom both

a decision granting tenure and a decision denying tenure

could be justified as a reasonable exercise of discretion by

the tenure-decision making body; (3) he was nevertheless

denied tenure; and (4) tenure positions were open at the

time he was rejected. 648 F.2d at 63.

-20-

1989), the Magistrate noted that plaintiff could satisfy

this burden by showing that the articulated reasons were

"obviously weak or implausible, or that the tenure standards

for prevailing at the tenure decisions were manifestly

unequally applied," but he also noted, quoting further from

the Court's decision in Brown, that "[t]he essential words

here are 'obviously' and ’manifestly1." and that a court or

jury "may not simply substitute its own views concerning the

plaintiff's qualifications for those of the properly

instituted authorities; the evidence must be of such

strength and quality as to permit a reasonable finding that

the denial of tenure was 'obviously' or 'manifestly'

unsupported." (App. 112a) (emphasis added).

The Magistrate's approach was clearly correct and

consistent with the decisions of this Court referred to

above. See also Griggs-Rvan v. Smith. 904 F.2d 112, 115

(1st Cir. 1990) ("Evidence which is merely colorable, or is

not significantly probative will not preclude summary

judgment."); Medina-Munoz v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.. 896

F •2d 5, 9 (1st Cir. 1990) ("So long as the employer proffers

[a valid, nondiscriminatory reason for its action], the

inference raised by plaintiff's prima facie case vanishes

[and] it is up to plaintiff, unassisted by the original

presumption, to show that the employer's stated reason was

-21-

but a pretext for age discrimination.")6; The Dartmouth

Review v. Dartmouth College. 889 F.2d 13, 16 (1st Cir. 1989)

(to avoid summary judgment, "plaintiffs must point, if not

to fire, at least to some still-warm embers; 'smoke alone is

not enough to force the defendants to a trial to prove that

their actions were not [racially] discriminatory.1") While

plaintiff may quarrel, as he does, with the result reached,

he cannot show that the Magistrate placed any improper

burden on him to defeat Wellesley's motion for summary

judgment. Neither the Magistrate nor the District Court did

any such thing.

6 Plaintiff argues that the Magistrate fundamentally

misunderstood the Title VII burdens of proof. (Brief of

Appellant at 44-46). The fact is, the Magistrate properly

followed Medina-Munoz' clear holding that to rebut the

employer's legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons, a Title

VII litigant must show that those reasons are "not only a

sham, but a sham to cover up . . . [improper]

discrimination." Plaintiff's real problem is not with the

Magistrate's decision, but with the holdings of Medina-

Munoz , Burdine and many other employment discrimination

cases. As discussed above at pp. 12 to 17, Medina-Munoz was

rightly decided and correctly followed. Plaintiff's case

was properly dismissed because he has not raised a genuine

issue of fact as to whether Wellesley's reasons for denying

him tenure were pretexts for unlawful discrimination.

Plaintiff has at most presented evidence from which a

factfinder might conclude that the tenure decision could

have gone either way. Such a showing is insufficient to

bring his case to a jury. See Pea v. Look. 810 F.2d 12, 15

(1st Cir. 1987)(plaintiff "cannot meet his burden of proving

'pretext' simply by refuting or questioning the defendants'

articulated reason").

-22-

B. The District Court Correctly Found That

Wellesley Articulated Legitimate,

Nondiscriminatory Reasons For The

Denial of Tenure to Plaintiff____________

The Magistrate found, and plaintiff does not seriously

dispute, that Wellesley articulated legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reasons for its denial of tenure to

plaintiff. The record shows that the members of the R&P

Committee who recommended against tenure for plaintiff --

j.e. , Professors Gascon-Vera, Roses and Renjilian-Burgy —

did so principally because they believed that, as a small

department, they needed a dynamic person who could attract

students and build course enrollments and that plaintiff had

not shown, either in his teaching, scholarship, or other

activities, that he was sufficiently exceptional to perform

this task.

More specifically, the majority members of the R&P

Committee noted with respect to plaintiff's teaching that

his pace was generally slow, he spoke too much English and

not enough Spanish, he spent a substantial amount of time

simply reading to the students, and he had a difficult time

in getting the students to actively participate in his

classes. They also noted that plaintiff's course

enrollments were generally low and that the evaluations

submitted by students who had taken plaintiff's courses -

-23-

referred to as "SEQs"7 - were "not poor by any means," but

they were "not of the superior quality that we seek in a

tenure candidate."

/ with respect to plaintiff's scholarship, the

majority members noted that:

plaintiff had concentrated his writing energies

not on scholarship but on writing and promoting his own poetry;

his published poetry was mainly written in the

1960s and 1970s (more recent poetry had not been published);

his doctoral dissertation should have been, but

never was, transformed into a published book;

his published scholarly articles were done in the

late 1970s and early 1980s, and were a reworking

of his doctoral dissertation;

plaintiff's critical methodology, although sound,

was not up-to-date or imbedded in the diverse

trends of criticism that have been current for the

last twenty years (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 34).

With respect to service to the Department and the

College, the majority members noted that plaintiff had

generally complied with requests from his Department

colleagues but had not taken the initiative either to

promote Departmental activities or to handle major new

Department responsibilities. Finally, with respect to

Department structure, the majority members noted that the

Department was small, with four of its six members already

Student Evaluation Questionnaires.

-24-

tenured, and the next candidate for tenure, Marjorie Agosin,

was an "internationally known poet with four books of

poetry, more than 30 scholarly articles and two books of

criticism, as well as superior student evaluations,

particularly in literature." The majority members also

noted that, under the College's lawful mandatory retirement

policy for tenured faculty, plaintiff would be due to retire

at virtually the same time as three Department members who

already had tenure.

Similarly, the undisputed evidence shows that the

members of the CFA who voted against an award of tenure for

plaintiff did so because of the R&P Committee's majority

recommendation and also because their own review of the

objective evidence in plaintiff's case, including the

student SEQ's, the faculty teaching reports and the outside

evaluations of plaintiff's written work, tended to confirm

that plaintiff's teaching was good, but not outstanding, and

that, while the quantity of plaintiff's scholarship was

adequate, he did not seem current in the latest trends of

literary criticism or to have adequate command of that

material (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 47).

The foregoing reasons are manifestly legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reasons for opposing an award of tenure,

and relate specifically to the standards set forth in the

-25-

College's Articles of Government. Thus, the Articles stated

that "[rjecommendation for promotion should always be based

upon evidence that the candidate is an able teacher and

possesses intellectual enthusiasm and power." The Articles

further stated that:

"In judging qualifications of candidates,

reference will be made to teaching ability,

evidence of scholarly strength and growth

including research activity and potential, the

relation of the candidate to his/her department's

structure, service to the College, including

assumption of departmental and College-wide

responsibilities, and external professional

activities" (Wellesley College's Articles of

Government, p. 61) (attached as Exhibit A to

Wellesley's memorandum in support of its motion

for summary judgment dismissing plaintiff's claims

of race, color, national origin and sex

discrimination).

In light of these provisions, and the materials

discussed above, there can be no question but that Wellesley

articulated legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons for the

denial of tenure to plaintiff. The Magistrate properly so

found.

-26-

C. There Was No Probative Evidence That

The Reasons Wellesley Articulated For The

Denial of Tenure to Plaintiff Were Obviously

Weak Or Implausible Or That Wellesley

Manifestly Applied An Unequal Standard

To Plaintiff's Tenure Application__________

The principal inquiry in this case is whether plaintiff

has demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that the

foregoing legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons for his

tenure denial were in fact a cover-up for unlawful

discrimination against him. Plaintiff concedes that he has

no "direct" evidence of discrimination. His attempt to show

pretext is based almost entirely on comparisons of his

ications with those of women granted tenure in the

Spanish Department. There is nothing else from which an

inference of discrimination on the basis of age, sex,

national origin or race is even remotely possible.

Where, as here, an unsuccessful candidate for tenure

challenges the university's decision with comparative

evidence, the Court must be especially sensitive to the risk

of "improperly substituting a judicial tenure decision for a

university one." Brown v. Trustees of Boston University.

891 F .2d 337, 347 (1st Cir. 1989). It is not sufficient to

show that the tenure decisions could have gone either way,

nor is it sufficient merely to demonstrate that some aspects

of plaintiff's case were stronger than some aspects of the

cases to which he compares himself. Rather, the comparative

-27-

evidence must be "so compelling as to permit a reasonable

finding of one-sidedness going beyond a mere difference in

judgment." Id. at 347 (emphasis added). Were the standard

of proof otherwise, the normal differences and unique set of

factors in every tenure case would permit the jury to make

the leap of faith that any denial of tenure was on account

of the protected classification into which the plaintiff

happened to fall.

This Circuit's rule that comparative evidence in tenure

cases must be compelling follows from the fact that a tenure

decision is necessarily a subjective evaluation of

professional performance at a very high level. Tenure

candidates by definition have been reappointed to their

assistant professorships and are deemed by the university

already to have met some minimum standard applicable to

college teaching and research. There always will be

differences among candidates, and there often will be

seeming inconsistencies among records, especially where, as

here, fragments of some records are compared with fragments

of other records. Such evidence does not show pretext for

unlawful discrimination.

Plaintiff's evidence falls far short of the standard

articulated by this Circuit. The Magistrate recognized that

the "majority of plaintiff's arguments center on [his claim]

-28-

that he was as qualified, if not more qualified, for tenure

as were four white women who were granted tenure." (App.

108a). The Magistrate concluded, however, that the specific

evidence plaintiff produced in an effort to show that this

was so was not sufficient to allow a rational trier of fact

to conclude, short of mere speculation or conjecture, that

Wellesley's articulated reasons for denying tenure to

plaintiff were mere pretexts for discrimination against him

on account of his sex, race, national origin or age.

In reaching this result, the Magistrate did not

improperly resolve factual disputes against plaintiff, as

plaintiff contends at pp. 42-44 of his Brief. Rather, the

Magistrate concluded that, even if true, the facts presented

by plaintiff were not sufficient to allow an inference of

improper discrimination (App. 108a, n. 11; App. 110a).

The Magistrate was plainly correct in concluding that

plaintiff's evidence as to his relative qualifications did

not permit a reasonable inference of discrimination.

Recommendations for tenure at Wellesley are to be "based

upon evidence that the candidate is an able teacher and

possesses intellectual enthusiasm and power" (App. 19a). A

candidate's record as a whole is taken into account, with

reference to the five specific factors articulated in the

faculty legislation (App. 19a). Plaintiff did no more than

-29-

compare isolated aspects of his overall record to isolated

aspects of the records of other persons granted tenure

before or after him. These misleading and fragmented

comparisons - which are plaintiff's entire case - fall far

short of the required showing that the reasons advanced for

denial of tenure to him were obviously weak or implausible,

or that the College manifestly applied an unequal standard

to his tenure application. See Brown v. Trustees of Boston

University, 891 F.2d 337, 346 (1st Cir. 1989).

1. The Tenure Candidacies of Professors

Renjilian-Burgy and Agosin Do Not Permit

A Reasonable Finding of One-Sidedness

The facts concerning the relative qualifications of

plaintiff and Professors Renjilian-Burgy and Agosin are

essentially undisputed. This evidence does not permit a

reasonable tridr of fact to conclude that in denying tenure

to plaintiff and granting it to his female non-Chicano

colleagues, Wellesley engaged in decision-making so one

sided as to go beyond a mere difference in judgment.

With respect to Professor Renjilian-Burgy, the

undisputed evidence shows that at the time she was awarded

tenure, Professor Renjilian-Burgy was generally regarded as

one of the most exceptional teachers at Wellesley and had

regularly received awards for her teaching, including the

Massachusetts Teacher of the Year award from the Spanish

-30-

Heritage Society in 1981, and a Pinanski prize for

excellence in teaching at Wellesley College in 1983

(Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 70).

The evidence likewise shows that, unlike plaintiff,

Professor Renjilian-Burgy had been extraordinarily active in

Departmental and College affairs, and also in outside

professional organizations. Thus, at the time Professor

Renjilian-Burgy was considered for tenure, she was an

elected member of the Faculty Advisory Committee to the CFA.

She was also serving on, or had served on, numerous other

Departmental and College committees, including, among

others, the Affirmative Action Task Force, the Intercultural

Awareness Now Committee, the Martin Luther King Memorial

Committee, and the Faculty Committee for the Stone Center

for Psychological Development. Professor Renjilian-Burgy

was also serving as faculty advisor to the "Alianza" student

organization, and she was also a freshman liaison, a group

discussion leader for freshman orientation and a faculty

member of the MIT Wellesley upward bound program. Finally,

Professor Renjilian-Burgy was First Vice President and

President-elect of the Massachusetts Foreign Language

Association, a member of the Board of Directors of the

Massachusetts chapter of the American Association of

Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, and an active member of

-31-

The extraordinary regard that students and colleagues

had for Professor Renjilian-Burgy was shown by the numerous

letters they wrote in support of her reappointments and

tenure. These letters were far more numerous and strong

than the letters written in plaintiff's case. Thus, one

student wrote that Professor Renjilian-Burgy1s "rigorous

teaching excellence, her kindness and compassion, her

commitment and drive, and her personal and professional

integrity distinguish her as an outstanding faculty member

and human being" (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 107). Another

wrote that Professor Renjilian-Burgy was an "invaluable

asset to the Spanish Department and the entire Wellesley

College community" (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 119).

There is likewise no guestion that the grant of tenure

to Professor Agosin raises no inference of discrimination.

Thus, the undisputed evidence shows that at the time she was

considered for tenure - i.e .. 1987-88 - Professor Agosin had

written three books of literary criticism, one book of

social commentary, 26 critical articles on various topics,

three published books of poetry, four creative publications

in anthologies, and three other works in progress and had

delivered numerous lectures and papers at meetings of

numerous other outside professional organizations (Nuwayser

Supp. Aff. Exh. 70).

-32-

Professor Agosin's scholarly output was not only

substantially greater than plaintiff's, it was also

continually growing. This was specifically noted by David

Ferry, a member of the CFA who voted in plaintiff's favor

but who testified that in his view, Professor Agosin was the

stronger candidate:

Q. Well, I understand your explanation as to why you

thought [Professor Agosin] was a strong candidate.

I guess my question is specifically and let's take

scholarship, why did you think her scholarship was

stronger than Professor Villanueva's?

A. Because it seemed to me on all three fronts, the

front of social writing, the front of literary

criticism, although I had some criticism of those,

and the poetry, although I had some criticisms of

that, to be continually productive and energetic

beyond the energies of what Tino had displayed.

The R&P Committee in Tino's case pointed out, for

example, that there was not much scholarly

production beyond the terms of the dissertation,

beyond the work done for the dissertation and so

on and compared with Marjorie Agosin this wasn't

the case. The poetry writing that Tino did dated

mainly from an earlier period and this is not the

case of Marjorie Agosin. So in those ways, she

seemed to me — seemed to me to be a superior

candidate. (Ferry Dep. pp. 60-61).

Professor Agosin's teaching abilities also plainly

supported her award of tenure. As Professor Ferry further

explained, whereas there appeared to be little demand for

the Chicano literature courses plaintiff was teaching, there

professional organizations around the world (Nuwayser Supp.

Aff. Exh. 128).

-33-

was a strong demand for the courses on Latin American

literature that Professor Agosin was teaching (Ferry Dep.

pp. 61-62). Here again, plaintiff's focus on an isolated

bit of evidence - the SEQ's - provides an incomplete and

misleading comparison. The entire record amply supports the

College's judgment that Professor Agosin was the better

teacher. Professor Ferry further testified:

I don't know whether Marjorie Agosin has created

such a demand but there certainly — there are a

large number of Latin American students at

Wellesley and students interested in the

literature of Latin America, especially South

America, and that is central to Marjorie Agosin's

interests as -- as it was not the case in Tino.

And that fact, the fact that she presented

positive curricular resources in ways that were

central to the curriculum of the department, had

to be taken into account.

Tino represented indeed a specialty that the

curriculum ought to have in it, but there was not

demonstrable a sizable demand for it at the

present time, nor was it demonstrated that he was

creating any demand. So they differ in that

regard as well. (Ferry Dep. p. 62).

The evidence further showed that Professor Agosin had

received uniformly excellent class visit reports and was

generally regarded as a dynamic and effective teacher by her

colleagues in the Spanish Department (Nuwayser Supp. Aff.

Exh. 138). Her courses were far more popular than

plaintiff's and elicited many favorable letters from

students. Professor Agosin had also been coordinator of the

PRESHCO program and had served as the Spanish Department's

-34-

liaison with various College committees or programs,

including the Women's Studies, Jewish Studies, and Foreign

Studies programs, and also the Pew Committee. Finally,

unlike plaintiff, Professor Agosin was extraordinarily

active on Departmental and College committees and also in

outside professional organizations. She had served on the

Advisory Board of the Massachusetts Foundation of the Arts

and the New England Council of Latin-American Studies, had

served as Chairperson of the International Institute of

Sisterhood is Global, and had been active in numerous other

professional organizations and activities outside the

College (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 127).

Rather than supporting plaintiff's claim of pretext,

the records of Joy Renjilian-Burgy and Marjorie Agosin

illustrated precisely the type of professional vigor, growth

and excellence that the members of the R&P Committee and CFA

were clearly looking for, but did not find, in plaintiff's

case. Both of them had a far greater impact on the growth

and vitality of the Spanish Department than plaintiff.

Notwithstanding all the foregoing evidence, plaintiff

says that evidence that a discriminatory "higher standard"

was applied to him can be found in the fact that he was

criticized for matters that were either minimized or ignored

in the other Spanish Department tenure cases. More

-35-

specifically, plaintiff says that his scholarship was

criticized even though Joy Renjilian-Burgy was awarded

tenure without ever having completed her Ph.D. dissertation.

He also says that his teaching was criticized even though

his SEQ's were the same or better than any of the other

Spanish Department tenure candidates except for Joy

Renj ilian-Burgy.

This approach by plaintiff overlooks the obvious fact

that the lack of significant ongoing accomplishment in one

area becomes a more serious problem, and more subject to

legitimate criticism, where it is not offset by significant

accomplishments in another. Once again, the evidence showed

that, unlike Joy Renjilian-Burgy, plaintiff was not

generally regarded as one of the most dynamic and effective

teachers at Wellesley and was not extraordinarily active in

Department and College affairs and outside professional

organizations. Accordingly, it is not surprising, or

indicative of a pretext for unlawful discrimination, that

the lack of significant, ongoing scholarship was regarded as

more of a problem in plaintiff's tenure case than it was in

Joy Renjilian-Burgy's .

Similarly, the evidence showed that, unlike plaintiff,

Professor Agosin was an extraordinarily prolific scholar,

regularly attracted numerous students to her courses and to

-36-

independent studies with her, and was extraordinarily active

both in the Department and College. The evidence also

showed that her colleagues who visited her courses found the

content excellent and the students actively involved. Under

these circumstances, once again, it is not surprising, or

indicative of discrimination, that the R&P Committee members

paid less attention to the SEQ's submitted in Professor

Agosin's case. There was a plethora of other evidence to

support the excellence of Professor Agosin's performance in

all the areas designated for consideration by Wellesley's

Articles of Government.

2. The Only Probative Comparisons Are to

Professors Reniilian-Burov And Agosin

Plaintiff compares himself to his female Spanish

Department colleagues granted tenure from 1977 through 1987.

However, only two of those comparisons - to Professors

Renjilian-Burgy and Agosin, whose tenure decisions bracketed

his own - could possibly be relevant in this case. The far

more remote tenure candidacies of Professors Gascon-Vera and

Roses are not probative of the decision made in plaintiff's

case because the decision makers were entirely different and

the Department structure was not at all similar.

Professor Gascon-Vera was considered for tenure in

1977, and Professor Roses in 1979. It is undisputed that

different individuals decided plaintiff's application and

-37-

the tenure applications of Professors Gascon-Vera and Roses.

The only R&P Committee member common to all three decisions

was Professor Lovett, who voted in favor of tenure each

time, and almost none of the CFA members who decided

plaintiff's case also participated in the previous cases.

The decisions of those other individuals and earlier

committees simply are not probative of the decision made on

plaintiff1s tenure application. See Medina-Munoz v. R.j.

Reynolds Co., 896 F.2d 5, 10 (1st Cir. 1990) ("The biases of

one who neither makes nor influences the challenged

personnel decision are not probative in an employment

discrimination case.").

Moreover, the Spanish Department was much more heavily

tenured in 1985 than it was in 1977 or 1979. The award of

tenure in 1985, in a department already heavily tenured,

would have a much more dramatic impact on future tenure

candidates than would earlier awards of tenure, especially

those occurring almost a decade ago. For that reason, it is

entirely possible that Wellesley's tenure standards may have

tightened over the years as there became fewer tenure slots

available. However, any difference in the tenure standards

from 1977 and 1979 to 1985 - even if such a difference were

shown - cannot be inferred to have had anything to do with

plaintiff's sex, age, race, color or national origin.

-38-

Banerjee v. Board of Trustees of Smith Collpgp, 648 F.2d 61,

66 (1st Cir. 1981) (higher standard applied to the

®^^buation of plaintiff's scholarship was due to changed

circumstances, and not to any discriminatory animus toward

plaintiff).

Even if the tenure decisions of Professors Gascon-Vera

and Roses are not too distant to be probative, there is

nothing in those cases that helps plaintiff. He cannot show

that, in comparison to them, the denial of tenure to him was

obviously weak or implausible. To the contrary, the

evidence showed that at the time they were awarded tenure,

both Professors Gascon—Vera and Roses had demonstrated the

type of vigorous ongoing development and activity in the

Spanish Department and College at large that was lacking in

plaintiff's case.

Thus, the evidence showed that at the time Professor

Gascon-Vera was awarded tenure in the Spanish Department in

academic year 1977-78, her Ph.D. dissertation on a 14th

century Spanish author Don Pedro had been accepted for

publication as a book, and she was working on a second book

on a 15th century Spanish author, Don Enrique de Villena.

Professor Gascon-Vera had also prepared several articles,

and had given numerous papers and lectures on academic

subjects to organizations around the world. Professor

-39-

Gascon-Vera was also an active member of the Modern Language

Association of America and numerous other professional

^rganizations, and was Chairman of the Language Laboratory

Committee at Wellesley (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 59).

Similarly, the evidence showed that at the time

Professor Roses was awarded tenure in academic year 1979-

80, the Spanish Department was offering a two-track major,

one for students specializing in Spanish Peninsular

literature and the other for students specializing in Latin

American literature, and Professor Roses was the most senior

person teaching Latin American literature. She had also

written numerous articles on contemporary Latin American

authors and was working on a full-length book on the Latin-

American novelist, Lino Novas-Calua. Also, like Professor

Gascon-Vera, Professor Roses was extremely active in the

Spanish Department and College and had delivered numerous

scholarly papers and lectures to professional organizations

around the world (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 61).

-40-

3. Plaintiff's Other Evidence Fails

To Show That The College's Articulated

Reasons Were Pretextual________________

Apart from the foregoing purported "comparisons,"

plaintiff also suggests that evidence of "pretext" or

unlawful discrimination can be found in letters that were

submitted by the Spanish Department in 1981 and 1982

supporting plaintiff's reappointment to his assistant

professor position. Quoting from the minutes of a CFA

meeting held on his tenure case in April, 1986, plaintiff

suggests that the shift between the earlier, positive

reappointment letters and the subsequent negative tenure

letter was so great and blatant as to suggest "dishonesty."8

The evidence shows, however, that one of the three

members of the R&P Committee which recommended against

tenure for plaintiff - Joy Renjilian-Burgy - did not

The probative value of the "dishonesty" comment is almost

nonexistent. It was made by unknown members of the CFA

during a consideration of plaintiff's appeal, when the CFA

would have been expected to have critically reexamined all

of the evidence pertinent to plaintiff's tenure candidacy,

including that which seemed to favor plaintiff. The only

legitimate inference that can be drawn from this comment is

that the CFA carefully scrutinized plaintiff's case and gave

him the benefit of a full and fair appeal. Far more

suggestive of the CFA's actual view of the merits of the

decision is that the appeal was denied and that the three

members of the CFA who voted for tenure stated that they

"did not feel strongly that Mr. Villanueva should be

tenured." (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 58, p. 2571).

-41-

participate in the earlier reappointment decisions.9

Another member - Lorraine E. Roses (then Lorraine E. Ben-

Ur) - wrote a teaching report at the time of the earlier

reappointment decisions which included some of the same

criticisms that were subsequently included in the negative

tenure letter. (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 14.) Both

Professors Roses and Elena Gascon-Vera - the third member of

the R&P Committee which recommended against tenure for

plaintiff - met with plaintiff in March, 1983 and

subsequently sent him a memorandum urging him to become more

active both within the Spanish Department and the College at

large. (App. 24a-25a; Nuwayser Supp. Aff. Exh. 18.) Once

again, plaintiff's failure to be more active in the

Department or College was one of the principal criticisms

expressed in the Committee's subsequent recommendation

against an award of tenure to plaintiff. (Nuwayser Supp.

Aff. Exh. 34.)

Thus, none of the three members of the R&P Committee

who recommended against tenure acted inconsistently with

their earlier positions. While some members of the CFA may

have been surprised by the alleged switch between the

Professor Renjilian-Burgy did not have tenure in 1981 or

1982 when plaintiff was reappointed and hence was not

eligible to be a member of the R&P Committee at that time.

-42-

reappointment and tenure decisions, there was manifestly

nothing at all dishonest about it.

In fact, such "switches" necessarily occur whenever

tenure is denied at Wellesley because, under the College's

Articles of Government, a candidate can not be considered

for tenure unless he or she has been earlier reappointed.

Rather than dishonesty, such switches at most suggest that

different decisions are being made under different

circumstances, with the most important changed circumstances

obviously being that the tenure decisions is forever, while

the reappointment decision is for at most three years. In

no sense did plaintiff's earlier reappointment by the

Spanish Department R&P Committee suggest that the reasons

the R&P Committee ultimately articulated for recommending a

denial of tenure to plaintiff were pretexts or cover-ups for

discrimination against plaintiff on account of his sex, age,

national origin or race. Cf. Cook County College Teachers

Union, Local 1600 v. Byrd, 456 F.2d 882, 899 n. 8 (7th Cir.

1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 484 (1972), reh. denied. 414

U.S. 883 (1972) (rejecting contention that positive earlier

reviews of teachers suggested impermissible factors had

affected subsequent negative reviews).

-43-

II. THERE WAS NO OTHER PROBATIVE EVIDENCE

OF IMPROPER DISCRIMINATION AGAINST

PLAINTIFF BECAUSE OF HIS RACE, COLOR,

NATIONAL ORIGIN OR SEX________________

The Magistrate correctly concluded that plaintiff's

statistical evidence was flawed because it failed to include

any data showing the number of "minority persons of Hispanic

origin" actually applying for positions in the Spanish or

other departments at Wellesley, or the number of such

persons who could reasonably be expected to apply absent

discriminatory hiring practices. Without such data, no

inference can be drawn from the number of such persons

actually employed at Wellesley. Wards Cove Packing Co. v.

Antonio. 109 S.Ct. 2115, 2122 (1989)("If the absence of

minorities holding such skilled positions is due to a dearth

of qualified nonwhite applicants (for reasons that are not

petitioners' fault), petitioners' selection methods or

employment practices cannot be said to have had a 'disparate

impact on nonwhites.'"); Jackson v. Harvard University. 721

F. Supp. 1397, 1430 (D. Mass. 1989)("Those figures [showing

but three tenured women at the Business School out of a

tenured facility of 84], while striking, are not in

themselves particularly probative in a discriminatory

treatment case [particularly in the absence of evidence

showing the qualified labor market]").

-44-

Plaintiff attempts to respond to this criticism by

asserting in his Brief (p. 48) that he had "accepted

Wellesley's submission for the purpose of summary judgment

that the relevant labor market was reflected by the national

average of 6.2% of minority (black and Hispanic) faculty

members in colleges and universities." Wellesley's

submission was, however, based on the Handbook of Labor

Statistics published by the U.S. Department of Labor

(Bulletin 2217 - June, 1985) which clearly included in its

count all persons of Hispanic origin, including white

persons.10 Plaintiff's purported comparison, which includes

only "full-time minority faculty members of Hispanic origin"

at Wellesley and arbitrarily excludes Hispanics whom he

cavalierly dismisses as "white women," is utterly

meaningless.

The appropriate statistical comparison is not what

different R&P Committees did years ago, but what the CFA did

in the 1985-1986 academic year, the year of Mr. Villanueva's

candidacy. There were 15 candidates for tenure in 1985-

1986, ten of whom were women and five of whom were men. Of

10 The Handbook specifically states that: "Hispanic origin

refers to persons who identify themselves in the enumeration

process as Mexican, Puerto Rican living on the mainland,

Cuban, Central or South American, or other Hispanic origin

or descent. Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race,

thus, they are included in both the white and black

population group." See Handbook, p. 3.

-45-

those candidates, six women and three men received tenure.

Likewise, four of the candidates were over 40 and eleven

were under 40. Of those candidates, three candidates over

40 and six candidates under 40 received tenure. Sixty

percent of the female candidates received tenure, as did

sixty percent of the male candidates. Seventy-five percent

of the candidates over 40 received tenure, while

approximately half of the candidates under 40 received

tenure and the other half did not (App. 52a). These

statistics do not support, but rather refute, any claim of

discrimination.

Plaintiff fares no better by examining the decisions of

the CFA for the entire period that plaintiff was employed by

the College. Here the evidence shows that during the period

from September, 1972 through June, 1986, 149 faculty members

were considered for tenure at Wellesley, and 98 of them were

granted such tenure. During this same period, 12 persons,

other than plaintiff, who were members of racial minority

groups (including Asians) or persons of Hispanic origin were

considered for tenure at Wellesley, and eight of them were

granted such tenure. (Nuwayser Supp. Aff. 55 9-10). Thus,

tenure was granted to 65.7% of all candidates and 66.7% of

minority candidates. Plaintiff can get no help from such

statistics. See generally. Baneriee v. Board of Trustees of

-46-

*

Smith College. 648 F.2d 61, 66 (1st Cir. 1979)(statistics

showing minority success rate in tenure decisions was

approximately the same as overall success rate not probative

of racial discrimination).

Plaintiff finally suggests (Brief of Appellant at pp.

48-49) that evidence of discrimination can be found in the

"patronizing" description of plaintiff contained in the

memorandum prepared by the R&P Committee majority

recommending against tenure for plaintiff and in a remark

allegedly made by one of plaintiff's colleagues that

plaintiff was "not very intelligent." In fact, the

sentences about which plaintiff complains are not

patronizing at all, but rather are a sensitive and

sympathetic appraisal of his skill as a poet. The

disappointment of the R&P Committee was that little of the

expressive content of plaintiff's poetry made its way into

his teaching, which was perceived as somewhat dull and

uninspired. There is, further, nothing at all about a

comment that someone is "not very intelligent" that would

permit an inference of discrimination on account of sex,

age, race, color or national origin.

-47-

*

III. PLAINTIFF'S CLAIM OF AGE DISCRIMINATION

WAS ALSO PROPERLY DISMISSED_____________

Plaintiff asserted in the District Court that his claim

of ^g^ discrimination could be based solely on the reference

to his projected retirement date contained in the memorandum

prepared by the R&P majority recommending against an award

of tenure to him (App. 123a). Since plaintiff has not