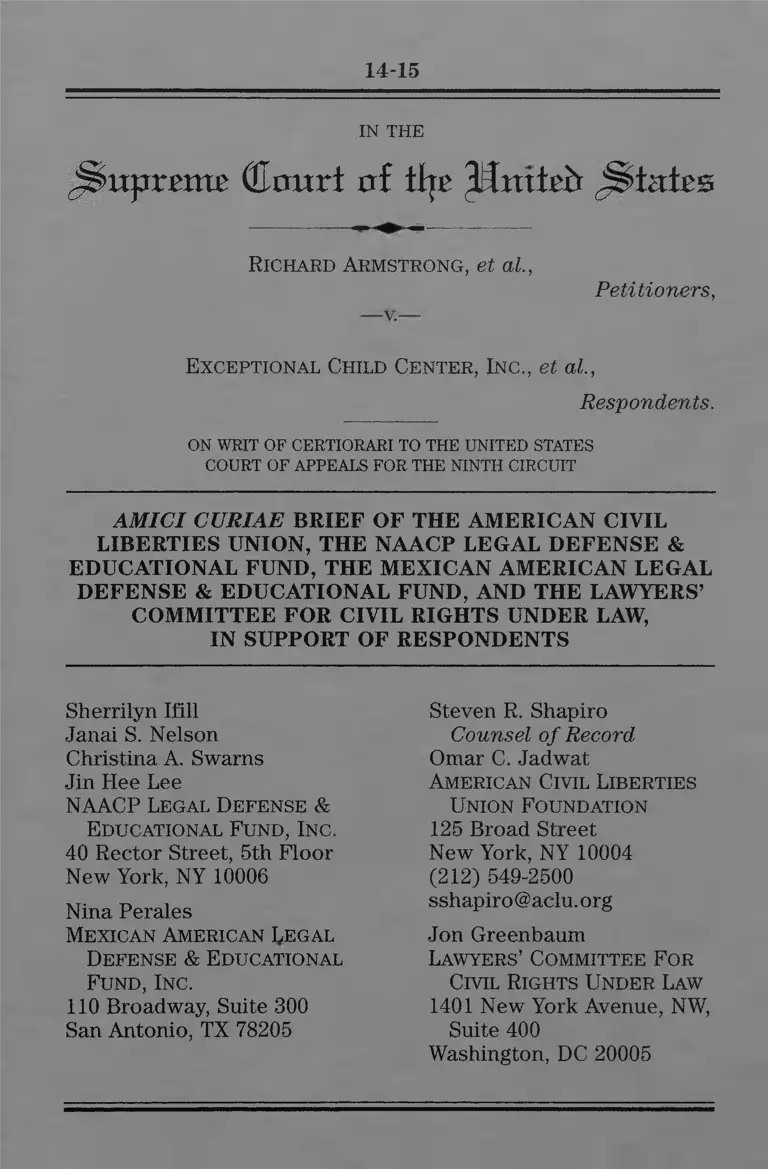

Armstong v. Exceptional Child Center, Inc. Amici Curiae Brief in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

December 22, 2014

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Armstong v. Exceptional Child Center, Inc. Amici Curiae Brief in Support of Respondents, 2014. 33b0ce6f-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95235c26-891d-49e1-b235-eeec5f559161/armstong-v-exceptional-child-center-inc-amici-curiae-brief-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 14, 2026.

Copied!

14-15

IN THE

npr txxxt (Sltmvi uf ti|t ffinxtzb i&tzs

R ic h a r d A r m s t r o n g , et a l,

Petitioners,

E x c e p t io n a l C h il d C e n t e r , In c ., et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION, THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, AND THE LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Sherrilyn Ifill

Janai S. Nelson

Christina A. Swarns

Jin Hee Lee

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

Nina Perales

M e x ic a n A m e r ic a n L e g a l

D e f e n s e & E d u c a t io n a l

F u n d , I n c .

110 Broadway, Suite 300

San Antonio, TX 78205

Steven R. Shapiro

Counsel o f Record

Omar C. Jadwat

A m e r ic a n C iv il L i b e r t i e s

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

sshapiro@aclu.org

Jon Greenbaum

La w y e r s ’ C o m m it t e e F o r

C iv il R ig h t s U n d e r La w

1401 New York Avenue, NW,

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

mailto:sshapiro@aclu.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................ iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE..................... l

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................... 2

ARGUMENT.............................. 5

I. THE JUDICIARY’S LONGSTANDING

AUTHORITY TO ENFORCE THE

CONSTITUTION THROUGH DIRECT

ACTIONS HAS BEEN PARTICULARLY

CRITICAL FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL

LIBERTIES............................................................... 5

A. Civil Rights Claims Have Long Been

Enforceable Through Direct Actions......... 6

B. Constitutional Claims Outside The Civil

Rights Context Have Also Long Been

Enforceable Through Direct Actions... . 12

C. The Supremacy Clause As Well May Be

Enforced Through Direct Equitable

Actions............................................... 16

II. PRECLUDING DIRECT RIGHTS OF ACTION

UNDER THE SUPREMACY CLAUSE WILL

HAVE BROAD AND HARMFUL

CONSEQUENCES FOR MAINTAINING THE

SUPREMACY OF FEDERAL LAW.................. 25

A. Racial and Ethnic Minorities, Immigrants,

Persons With Disabilities, And Low-Income

Individuals Continue To Depend On Direct

Actions Under The Supremacy Clause

To Challenge Invalid State And Local

Laws................................................... ............25

1

B. Precluding Rights Of Action Under The

Supremacy Clause Would Undermine

Im portant Federal In terests......................29

CONCLUSION................. ................. ...... ................ . 34

n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Allen v. Baltimore & Ohio R.R. Co.,

114 U.S. 311 (1884)................................................... 13

Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus,

438 U.S. 234 (1978)................................................... 14

Arizona u. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona,

133 S. Ct. 2247 (2013)....................................... 17, 21

Arizona u. United States,

132 S. Ct. 2492 (2012) .............................................. 17

Arkansas Dep’t of Health & Human Serus. v.

Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268 (2006)..................... 16, 17, 32

Asakura v. City of Seattle,

265 U.S. 332 (1924)................................................... 17

Bell v. Hood,

327 U.S. 678 (1946).................................................... n

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents o f Fed. Bureau

of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971)........................... 11

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).............. 3 , 7, 9

Bond v. United States,

131 S. Ct. 2355 (2011).......................................... 6 , 15

Brown v. Bd. of Educ.,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)...................................................... 8

Cannon v. Univ. of Chi.,

441 U.S. 677 (1979)................................................... 31

Carlson v. Green,

446 U.S. 14 (1980)..................................................... 11

iii

Chamber of Commerce v. Edmondson,

594 F.3d 742 (10th Cir. 2010) ................................. 26

Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting,

131 S. Ct. 1968 (2011) .... .................... .............. 26, 32

Chambers v. Florida,

309 U.S. 227 (1940) ..................... ................ ............... 7

Chicago Burlington & Quincy R.R. Co. v. City of Chi.,

166 U.S. 226 (1897)............... ......... ..................... . 13

Comacho v. Tex. Workforce Comm’n,

408 F.3d 229 (5th Cir. 2005)................................... 28

Corr. Servs. Corp. v. Malesko,

534 U.S. 61 (2001) .................. .............. .................... 11

Crosby v. City of Gastonia,

635 F.3d 634, 640-641 (4th Cir.) (noting issue),

cert, denied, 132 S. Ct. 112 (2011).................... . 14

Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council,

530 U.S. 363 (2000) .......... ......... ............ 18, 20 , 22

Dennis v. Higgins,

498 U.S. 439 (1991).................. ............................... 13

District of Columbia v. Carter,

409 U.S. 418 (1973) ......................................... ....... . 7

Douglas v. Independent Living Center of S. Cal.,

132 S. Ct. 1204 (2012) ..................... ................. ....... 19

Ex Parte Young,

209 U.S. 123 (1908)..................... ............. 14, 15, 16

Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v. Paul,

373 U.S. 132 (1963)......................................... 17

Foster v. Love,

522 U.S. 67 (1997) ....... ........................... .................. 18

IV

Free Enter. Fund u. Public Co. Accounting Oversight

Bd., 130 S. Ct. 3138 (2010)...................................... 15

Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights v. Deal,

691 F.3d 1250 (11th Cir. 2012) .............................. . 27

Golden State Transit Corp. v. City of Los Angeles,

493 U.S. 103 (1989)............................................ 18, 19

Green v. Mansour,

474 U.S. 64 (1985)..................................................... 15

Guinn v. United States,

238 U.S. 347 (1915)................................................... 9

Hays v. Port of Seattle,

251 U.S. 233 (1920) ................................................... 13

Hines v. Davidowitz,

312 U.S. 52 (1941).............................................. 17, 22

Kemp v. Chicago Housing Authority,

No. 10-cv-3347 (N.D. 111. July 21, 2010)............... 27

Lankford v. Sherman,

451 F.3d 496 (8th Cir. 2006)................................... 28

League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Wilson,

997 F. Supp. 1244 (C.D. Cal. 1997)............... ........ 27

Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly,

533 U.S. 525 (2001)........... ....................................... 18

Lozano v. City of Hazleton,

724 F.3d 297 (3d Cir. 2013), cert, denied, 134 S. Ct.

1491 (Mar. 3, 2014)............................................. 27, 32

Maine v. Thiboutot,

448 U.S. 1 (1980)....................................................... 17

Marbury v. Madison,

5 U.S. (1 Cranch) (1803)........................................ 5, 6

McLaurin v. Okla. State Regents for Higher Educ.,

339 U.S. 637 (1950).................................................... 8

Monroe v. Pape,

365 U.S. 167 (1961) .......................... ...................... • • 7

New York v. United States,

505 U.S. 144 (1992) ......................................... ......... 15

Osborn v. Bank of United States,

22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) (1824)................ ........ ....... . 13, 16

Patsy v. Bd. of Regents of Fla.,

457 U.S. 496 (1982).............. ............... .......... ......... 23

Pharm. Research & Mfrs. of America v. Walsh,

538 U.S. 644 (2003) ............................... 16, 18, 21, 30

Pierce v. Society of Sisters,

268 U.S. 510 (1925).............. .......... .................... 3, 10

Printz v. United States,

521 U.S. 898 (1997) .................................................. 15

Raich v. Truax,

219 F. 273 (D. Ariz. 1915......................................... 12

Rowe v. New Hampshire Motor Transp. A ss’n,

552 U.S. 364 (2008).................................................. 17

Scott u. Donald,

165 U.S. 107 (1897).......... ..................... ................ 13

Shaw v. Delta Air Lines, Inc.,

463 U.S. 85 (1983).................... ................................ 18

Soc’y of Sisters v. Pierce,

296 F. 928 (D. Or. 1924)........................................... 10

South Carolina v. Baker,

485 U.S. 505 (1988) ........................... ....................... 15

vi

South Dakota v. Dole,

483 U.S. 203 (1987).................................................. 15

Terrace v. Thompson,

263 U.S. 197 (1923).................................................. 10

Terry v. Adams,

345 U.S. 461 (1953)................................................ 3, 9

Toll u. Moreno,

458 U.S. 1 (1982)................................................ 21, 22

Truax v. Raich,

239 U.S. 33 (1915)............... ............................3, 9, 12

United States v. Alabama, ll-cv-02746 (N.D. Ala.

Aug. 1, 2011), preliminary injunction a ff’d in part

and rev’d in part, 691 F.3d 1269 (11th Cir. 2012),

cert, denied, 133 S. Ct. 2022 (2013)........................ 20

United States v. Arizona, 10-cv-01413 (D. Ariz. July

6 , 2010), preliminary injunction a ff’d in part and

rev’d in part, 132 S. Ct. 2492 (2012)...................... 20

United States v. Locke,

529 U.S. 89 (2000).................................................... 18

United States v. South Carolina,

720 F.3d 518 (2012).............................. ................... 27

Valle del Sol Inc. v. Whiting,

732 F.3d 1006 (9th Cir. 2013), cert, denied, 134 S.

Ct. 1876 (Apr. 21, 2014).... ......................................26

Vicksburg Waterworks Co. v. Mayor & Aldermen of

Vicksburg, 185 U.S. 65 (1902)................................. 13

Villas at Parkside Partners v. City of Farmers

Branch, 726 F.3d 524 (5th Cir. 2013),

cert, denied, 134 S. Ct. 1491 (Mar. 3, 2014)..........27

vii

Webster v. Doe,

486 U.S. 592 (1988).............. ......................................6

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

343 U.S. 579 (1952) ........................... ........................ 15

STATUTES

U.S. Const.

Art. I, § 8 , cl. 1 (Spending Clause)...................passim

Art. I, § 10 (Contracts Clause)......................... passim

Art. I, § 8 , cl. 3 (Commerce Clause)................ passim

Art. VI, cl. 2 (Supremacy Clause)............ ....... passim

Amend. V ..... ............... ....... ....................................... . 7

Amend. XIV....................... ................ .................passim

Amend. XV......................................................... . 9, 23

42 U.S.C. § 1983......................... .......................... passim

Act of Dec. 29, 1979, Pub. L. No. 96-170, § 1,

93 Stat. 1284....................... ........... .............................8

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Bradford C. Mank, Suing Under § 1983: The Future

After Gonzaga University v. Doe, 39 Hous. L. Reu.

1417 (2003)................................................................. 30

David Sloss, Constitutional Remedies for Statutory

Actions, 89 Iowa L. Rev. 355, 406 (2004)........ 23, 32

Federalist No. 33 (H am ilton)............ ................. . 16

Federalist No. 78 (H am ilton).......................... .............6

viii

Harry A, Blackmun, Section 1983 and Federal

Protection of Individual Rights—Will the Statute

Remain Alive or Fade Away?, 60 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1

(1985).............................................................................8

Hart & Wechsler’s The Federal Courts & The Federal-

System (Fallon et al. eds., 6th ed. 2009)............... 18

Jane Perkins, Medicaid: Past Successes and Future

Challenges, 12 Health Matrix 7 (2002)..................30

Lisa E. Key, Private Enforcement of Federal Funding

Conditions Under § 1983: The Supreme Court’s

Failure to Adhere to the Doctrine of Separation of

Powers, 29 U.C. Davis L. Reu. 283 (1996)............ 30

M arsha S. Berzon, Securing Fragile Foundations:

Affirmative Constitutional Adjudication in Federal

Courts, 84 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 681 (2009).......................8

M atthew C. Stephenson, Public Regulation of Private

Enforcement: The Case for Expanding the Role of

Administrative Agencies,

91 Va. L. Reu. 93 (2005)........................................... 32

Roderick M. Hills, Dissecting the State: The Use of

Federal Law to Free State and Local Officials from

State Legislatures’ Control, 97 Mich. L. Reu. 1201

(1999)........................................................................... 31

Rodney A. Smolla, Federal Civil Rights Acts § 14:2

(3d ed. 2011).............. 9

Susan Bandes, Reinventing Bivens: The Self-

Executing Constitution, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev. 289

(1995)............. 8

IX

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE'

The Am erican Civil L iberties Union

(“ACLU”) is a nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan

organization with over 500,000 members, dedicated

to the principles of liberty and equality embodied in

the Constitution and our nation’s civil rights laws.

Founded in 1920, the ACLU has vigorously defended

civil liberties for over ninety years, working daily in

courts, legislatures and communities to defend and

preserve the individual rights and liberties tha t the

Constitution and laws of the United States

guarantee everyone in this country. The ACLU has

appeared before this Court in numerous civil rights

cases, both as direct counsel and as amicus curiae.

The NAACP Legal D efense & Educational

Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) is a non-profit legal organization

established to assist African Americans and other

people of color in securing their civil and

constitutional rights. For more than six decades,

LDF attorneys have represented parties and

appeared as amicus curiae in litigation before the

Supreme Court and other federal courts on m atters

of race discrimination, including through the type of

direct constitutional enforcement actions at issue in

this case.

The M exican Am erican Legal D efense and

Educational Fund (“MALDEF”) is a national civil

rights organization established in 1968. Its principal

1 All parties have filed b lanket consents to the subm ission of

th is am icus brief. No counsel for a party au thored th is brief in

whole or in part, and no person, o ther th an the amici curiae,

th e ir mem bers, or th e ir counsel m ade any m onetary

contribution to the prepara tion or subm ission of th is brief.

1

objective is to promote the civil rights of Latinos

living in the United States through litigation,

advocacy and education. MALDEF has represented

Latino and minority interests in civil rights cases in

the federal courts throughout the nation, including

the Supreme Court. MALDEF’s mission includes a

commitment to protect the rights of immigrant

Latinos in the United States, and MALDEF has

asserted preemption theories in federal court to

further this commitment.

The Law yers’ Com m ittee for Civil R ights

Under Law (“Lawyers’ Committee”) is a national

non-profit civil rights organization th a t was founded

in 1963 at the request of President John F. Kennedy

to m arshal the resources of the private bar to defend

the civil rights of racial minorities and the poor. For

over fifty years, the Lawyers’ Committee has been at

the forefront of many of the most significant cases

involving race and national origin discrimination,

including many involving Constitutional claims. The

Lawyers’ Committee ability to vindicate the

Constitutional rights of its clients is dependent upon

the openness of the federal courts to hearing those

claims.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Enforcement of the Constitution is not

dependent on affirmative action by the political

branches of government. Rather, from this Nation’s

earliest times to the present, the federal courts have

consistently exercised their equitable powers to

compel compliance with the Constitution, without

suggesting the necessity for a statutory vehicle, such

as 42 U.S.C. § 1983, for such authority. Those

2

equitable powers have been, and continue to be,

particularly im portant for racial and ethnic

minorities, immigrants, persons with disabilities,

low-income individuals, and others whom our

m ajoritarian political processes are often unwilling

or unable to protect against constitutional violations.

Indeed, direct actions brought to enforce compliance

with the Constitution have resulted in many of this

Court’s most im portant civil rights and civil liberties

decisions, including Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1954), Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953), Truax v.

Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915), and Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925); in none of those cases

did the Court suggest tha t it was acting under § 1983

or another statutory vehicle. That history is

consistent with the many cases in which this Court

enforced other provisions of the Constitution, such as

the Contracts Clause and Commerce Clause, as well

as structural principles of federalism and separation

of powers.

Such direct actions are also available to

enforce a claim of preemption under the Supremacy

Clause, including where the preemption is based on a

statu te enacted under Congress’s spending power.

This Court has entertained and sustained many

direct actions based on federal preemption,

recognizing the appropriateness of such actions to

vindicate the supremacy of federal law. Petitioner

suggests th a t direct preemption actions should be

drastically restricted to situations in which federal

law creates a defense to threatened state action, but

that rule would seriously undermine the supremacy

of federal law. In many contexts, a direct action is

the only way in which the supremacy of federal law

can be established. Moreover, allowing plaintiffs to

3

raise their Supremacy Clause claims alongside other

constitutional claims is more efficient than

Petitioner’s overly restrictive approach.

Direct actions rem ain critical to vindicate the

supremacy of federal law. This is especially true for

racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, persons

with disabilities, and low-income individuals, who in

many circumstances have difficulty obtaining access

to, or support from, the federal political branches,

and who often depend on a judicial remedy to prevent

enforcement of state laws tha t conflict with federal

laws. In contexts as diverse as immigration, housing,

and public assistance, direct actions rem ain the only

effective avenue to ensure the supremacy of federal

law. Eliminating tha t avenue would seriously

undermine the force and power of federal law.

For practical and political reasons, the United

States does not bring enforcement actions against

every state law th a t violates the Supremacy Clause.

Termination of federal funding is even rarer and can

be counterproductive. Absent direct actions brought

to establish the supremacy of federal law by those

most directly affected by preempted state laws, there

would frequently be no meaningful remedy for state

noncompliance with this fundam ental Constitutional

safeguard.

4

ARGUMENT

I. THE JUDICIARY’S LONGSTANDING

AUTHORITY TO ENFORCE THE

CONSTITUTION THROUGH DIRECT

ACTIONS HAS BEEN PARTICULARLY

CRITICAL FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND

CIVIL LIBERTIES.

This Court has long recognized that the

strictures of the Constitution may be enforced

through direct actions for equitable relief, regardless

of whether Congress has enacted legislation

specifically establishing a cause of action for such

relief. So long as the court has subject-matter

jurisdiction over the claim, separate legislation

establishing a cause of action has never been

necessary for a plaintiff to obtain forward-looking

relief from unconstitutional conduct. Rather, the

traditional equitable authority of the courts has

always been deemed sufficient to provide such a

remedy. The Court has adhered to this principle in

many contexts—whether the constitutional claim

was brought against federal, state, or local officials;

whether the claim was brought to enforce individual

constitutional rights or to enforce structural

principles in the Constitution; and whether or not

the claim was brought to preclude an anticipated

enforcement action.

The courts’ inherent equitable authority to

compel compliance with the Constitution is implicit

in the structure of the Constitution itself, and in the

Constitution’s status as the supreme law of the land.

See Resp. Br. 7-15. As the Court recognized in

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803),

5

judicial review is necessary as a check against the

aggrandizement of power by the political branches.

These structural principles not only protect each

branch from intrusion by the others, but they also

protect individuals from the abuse of governmental

power. See Bond v. United States, 131 S. Ct. 2355,

2363-2364 (2011). Thus, as Chief Justice M arshall

explained, “[t]he very essence of civil liberty” is “the

right of every individual to claim the protection of the

laws, whenever he receives an injury.” 5 U.S. (1

Cranch) at 163. Although federal legislation may

channel the way in which constitutional claims are

entertained by the courts, the courts have long

understood th a t the right to compel compliance with

the Constitution is not contingent on the assent of

the political branches. See Webster v. Doe, 486 U.S.

592, 603 (1988) (stressing tha t a ‘“serious

constitutional question’” would arise if the political

branches attem pted to preclude any judicial forum

for constitutional claims by failing to make statutory

allowance for such claims); see also Federalist No. 78

(Hamilton) (“[T]he courts were designed to be an

intermediate body between the people and the

legislature, in order . . . to keep the la tter within the

limits assigned to their authority.”).

A. Civil R ights Claims Have Long Been

Enforceable Through D irect Actions.

The ability to enforce rights directly under the

Constitution has been particularly im portant for

racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, persons

with disabilities, low-income individuals, and other

persons who have faced systemic barriers in our

m ajoritarian political process and thus have often

depended on the federal courts to secure their rights

6

when Congress and the Executive Branch have been

unable or unwilling to do so.2 Some of this Court’s

(and this country’s) most significant steps toward

achieving equality and liberty have resulted from

plaintiffs’ enforcement of their rights directly under

the Constitution. And tha t was particularly true in

the long period before this Court’s decision in Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961), which revived 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 as a vehicle for private enforcement of

constitutional rights.

Many landm ark civil rights decisions resulted

from direct actions to enforce the Constitution. One

such case, Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), is a

keystone of this Court’s desegregation precedent. The

Bolling plaintiffs challenged racial segregation in the

public schools of the District of Columbia under the

Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. The

Court ruled unanimously for the plaintiffs, holding

tha t racial segregation in the District’s public schools

violated the Fifth Amendment. The Court nowhere

suggested tha t the plaintiffs’ ability to be heard on

their due process claim depended on their ability to

point to a statutory cause of action, such as § 1983.3

2 See Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 241 (1940) (“U nder our

constitu tional system, courts s tand against any winds th a t blow

as havens of refuge for those who m ight otherw ise suffer be

cause they are helpless, weak, outnum bered, or because they

are non-conforming victims of prejudice and public

excitem ent.”).

3 Indeed, a t the time, it was an open question w hether § 1983

applied to th e D istrict of Columbia. The Court did not address

the question un til District o f Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973), w hich held th a t § 1983 did not apply to persons acting

under color of D.C. law. Congress la te r am ended § 1983 to apply

to such persons. Act of Dec. 29, 1979, Pub. L. No. 96-170, § 1, 93

7

Desegregation in higher education was

advanced through another direct constitutional

action, McLaurin u. Okla. State Regents for Higher

Educ., 339 U.S. 637 (1950). After the University of

Oklahoma denied the plaintiff admission to graduate

school on the basis of his race, McLaurin sued for

injunctive relief, alleging tha t the state law

prohibiting integrated schools deprived him of equal

protection. The district court agreed. The Oklahoma

legislature then amended the statute, allowing the

university to admit the plaintiff but restricting him

to segregated facilities. The plaintiff returned to the

district court to seek injunctive relief, which the

district court denied. The Supreme Court reversed,

holding th a t the amended state law perm itting

segregated facilities deprived McLaurin of his right

to equal protection. Id. a t 642. The Court nowhere

suggested th a t McLaurin’s ability to bring his

constitutional claim depended on a statutory cause of

action .4

Stat. 1284.

4 A nother landm ark desegregation case, Brow n v. Bel. o f Educ.,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)—which also did not m ention the

predecessor s ta tu te to § 1983—can be seen as a direct

constitu tional action as well, although com m entators disagree

on how to characterize th a t case. Compare M arsha S. Berzon,

Securing Fragile Foundations: A ffirm ative C onstitutional

A djudication in Federal Courts, 84 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 681, 685-686

(2009) (characterizing Brown as a direct constitu tional action)

and Susan Bandes, Reinventing Bivens: The Self-Executing

Constitution, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev. 289, 355 (1995) (same), with

H arry A. B lackm un, Section 1983 and Federal Protection o f

Ind iv idua l R ights— Will the S ta tu te R em ain Alive or Fade

Away?, 60 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1, 1-2, 19 (1985) (characterizing

Brown as a § 1983 suit) and Rodney A. Smolla, Federal Civil

Rights Acts § 14:2, a t 391-392 (3d ed. 2011) (same). Regardless,

8

In an equally im portant decision for minority

voting rights, the Court in Terry u. Adams, 345 U.S.

461 (1953), sustained a constitutional challenge by

black citizens to one of a series of schemes to

m aintain whites-only primary elections in Texas.

Having abandoned their claim for damages, the

Terry plaintiffs rested their equitable claims directly

on the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Id. at

478 nn.2 & 3 (Clark, J. concurring). The Court struck

down the racially discriminatory primary as

unconstitutional. Id. at 470; see also id. a t 467 n.2

(plurality opinion) (noting tha t the Fifteenth

Amendment is “‘self-executing’”). In so ruling, the

Court relied on its earlier decision in Guinn v. United

States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915), which invalidated

grandfather clauses under the Fifteenth

Amendment, even though Congress had not enacted

specific legislation reaching primary elections, due to

“the self-executing power of the 15th Amendment,”

id. a t 368.

Several of this Court’s pathm arking decisions

establishing the rights of non-citizens also reached

the Court by way of direct action. For example, in

Truax u. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915), this Court held

tha t an Arizona statute prohibiting the employment

of non-citizens violated their rights to equal

protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. The

Court did not suggest th a t the case was before it

under a statutory cause of action, such as § 1983, but

ra ther stressed th a t the plaintiff had invoked the

equitable power of the district court to restrain

Bolling dem onstrates th a t there is a direct righ t of action under

the C onstitution to challenge the legality of racial segregation

in public schools.

9

unconstitutional action. Similarly, in Terrace v.

Thompson, 263 U.S. 197 (1923), the Court, although

rejecting an im m igrant’s constitutional claim on the

merits, stressed tha t the power to compel compliance

with the Constitution rested on the courts’

traditional equitable powers, noting that equity

jurisdiction will be exercised to enjoin

unconstitutional state laws “wherever it is essential

in order effectually to protect property rights and the

rights of persons against injuries otherwise

irremediable.” Id. a t 214.

Similarly, one of this Court’s leading decisions

on the meaning of “liberty” within the Due Process

Clause, Pierce v. Soc’y of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925),

arrived at the Court by way of a direct action brought

to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment and to prevent

Oregon officials from implementing a state

compulsory education law th a t would have forced all

children to attend public schools. See id. at 530. The

Court nowhere referred to a statutory cause of action

under which the claim for equitable relief was

brought. The district court where the case was

originally brought observed th a t “[t]he question as to

equitable jurisdiction is a simple one, and it may be

affirmed that, without controversy, the jurisdiction of

equity to give relief against the violation or

infringement of a constitutional right, privilege, or

immunity, threatened or active, to the detriment or

injury of a complainant, is inherent, unless such

party has a plain, speedy, and adequate remedy at

law.” Soc’y of Sisters v. Pierce, 296 F. 928, 931 (D. Or.

1924) (emphasis added).

This theme—th a t the courts have inherent

authority to restrain violations of the Constitution,

10

so long as they have subject-matter jurisdiction—

runs throughout the Court’s decisions and has never

been seriously questioned. In Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S.

678, 684 (1946) (footnote omitted), the Court

observed th a t “it is established practice for this Court

to sustain the jurisdiction of federal courts to issue

injunctions to protect rights safeguarded by the

Constitution and to restrain individual state officers

from doing what the 14th Amendment forbids the

State to do”—without any mention of a statutory

vehicle such as § 1983. And although Justices of this

Court have debated whether damages should be

available to remedy past constitutional violations in

the absence of a statutory cause of action, see Bivens

v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Fed. Bureau of

Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971); Corr. Servs. Corp. v.

Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 75 (2001) (Scalia, J.,

concurring), the Court has never questioned courts’

inherent authority to enjoin threatened or ongoing

constitutional violations. See, e.g., Carlson v. Green,

446 U.S. 14, 42 (1980) (Rehnquist, J., dissenting)

(criticizing direct constitutional actions for damages,

but acknowledging tradition of direct constitutional

actions for equitable relief, and noting that “[t]he

broad power of federal courts to grant equitable relief

for constitutional violations has long been

established”).

Moreover, contrary to Petitioner’s assertion

(Pet. Br. 40), the Court has entertained such direct

actions to enforce the Constitution regardless of

whether they were “an anticipatory defense to state

enforcement or regulation of the plaintiffs conduct.”

See infra pp. 19-22; see also Pet. Br. 45-46 (noting

several preemption cases tha t did not involve

anticipatory defenses). Indeed, where the plaintiff

11

could not bring the claim defensively to an

enforcement action, the case for exercise of the

courts’ equity power is particularly compelling

because the plaintiff could well have no other way to

vindicate his constitutional rights. In the

desegregation and voting rights cases discussed

above, for example, there was no clear way for the

plaintiffs seeking to vindicate their constitutional

rights to have obtained a ruling on the m erits of their

claims except through affirmative litigation. And in

Truax, the district court observed tha t the non

citizen’s constitutional claim presented an

appropriate case for the exercise of equity power

because, under the challenged Arizona statute, only

employers, not (non-citizen) employees, were subject

to criminal prosecution; thus, the non-citizen

employee would have had no other forum for his or

her claim to be heard. Raich v. Truax, 219 F. 273,

283-284 (D. Ariz. 1915). If a plaintiff seeking to

enforce the Constitution has no other forum in which

to raise his or her claim, tha t provides a stronger—

not a weaker—rationale for the courts to entertain a

direct equitable action.

B. C onstitutional Claims O utside The

Civil R ights Context Have Also Long

Been Enforceable Through D irect

Actions.

These civil rights cases are in keeping with

historical tradition, in which this Court has long

recognized direct actions to enforce constitutional

provisions, regardless of whether Congress has

provided a specific statutory vehicle for enforcement

of the Constitution.

12

One of the earliest examples is Osborn v. Bank

of United States, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 738 (1824), in

which this Court resolved the Bank of the United

States’ suit against the Ohio Auditor for collecting a

state tax that conflicted with the federal statu te that

created the Bank. Although no statute created a

cause of action for the Bank, this Court found that

the dispute w arranted the “interference of a Court,”

and it held the Ohio law unconstitutional on the

ground tha t it was “repugnant to a law of the United

States” and, therefore, void under the Supremacy

Clause. Id. a t 838, 868 .

In the years after Osborn, and with increasing

frequency after Congress provided for federal-

question jurisdiction in 1875, courts routinely

entertained suits to enforce directly a broad range of

constitutional provisions, including the Contracts

Clause, the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process

Clause, and the dormant Commerce Clause. See, e.g.,

Hays v. Port of Seattle, 251 U.S. 233 (1920) (Due

Process Clause and Contracts Clause); Vicksburg

Waterworks Co. v. Mayor & Aldermen of Vicksburg,

185 U.S. 65 (1902) (Contracts Clause); Chicago

Burlington & Quincy R.R. Co. v. City of Chi., 166

U.S. 226 (1897) (Due Process Clause); Scott v.

Donald, 165 U.S. 107 (1897) (Commerce Clause);

Allen v. Baltimore & Ohio R.R. Co., 114 U.S. 311

(1884) (Contracts Clause).

The direct actions for equitable relief brought

to enforce the Contracts Clause are particularly

noteworthy because this Court has not settled

whether claims under the Contracts Clause may be

brought under § 1983. See Dennis u. Higgins, 498

U.S. 439, 456-457 (1991) (Kennedy, J., dissenting);

13

Crosby v. City of Gastonia, 635 F.3d 634, 640-641

(4th Cir.) (noting issue), cert, denied, 132 S. Ct. 112

(2011). Nonetheless, the Court explained in

Vicksburg Waterworks th a t the Contracts Clause

claim was properly before it because “the case

presented by the bill is within the meaning of the

Constitution of the United States and within the

jurisdiction of the circuit court as presenting a

Federal question”—without suggesting tha t a

statutory cause of action was also necessary. 185

U.S. a t 82. The Court more recently upheld a

Contracts Clause claim in a direct-action posture in

Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus, 438 U.S. 234

(1978), without discussing whether the claim might

have been brought under § 1983.

One of the most notable of these cases was Ex

Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908). After the

Minnesota Attorney General signaled his intention to

enforce a state law limiting the rates tha t railroads

could charge, a group of railroad shareholders sued

him to enjoin enforcement of that law, arguing tha t it

violated the Commerce Clause and Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court

concluded tha t the Eleventh Amendment does not

bar suits against state officers to enjoin violations of

the Constitution or federal law. Id. a t 159-160. The

Court also concluded th a t the federal courts had

jurisdiction because the case raised “Federal

questions” directly under the Constitution. Id. at

143-145. The Court thus viewed the Constitution—

paired with the federal-question jurisdiction

statute—as providing the basis of the plaintiffs’ right

to sue a state officer to enjoin an alleged

constitutional violation. As this Court has observed,

“the availability of prospective relief of the sort

14

awarded in Ex parte Young gives life to the

Supremacy Clause. Remedies designed to end a

continuing violation of federal law are necessary to

vindicate the federal interest in assuring the

supremacy of tha t law.” Green v. Mansour, 474 U.S.

64, 68 (1985). Indeed, scholars have concluded that

“the best explanation of Ex parte Young and its

progeny is that the Supremacy Clause creates an

implied right of action for injunctive relief against

state officers who are threatening to violate the

federal Constitution and laws.”5

Also demonstrating this principle are the

numerous cases in which this Court has resolved

structural constitutional claims brought against the

federal government without suggesting th a t a

statutory cause of action was necessary for those

claims to be before the courts, and where there was

no evident alternative forum for those claims to be

heard (such as under the Administrative Procedure

Act or in defense to an enforcement action). See

Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997); New

York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144 (1992); South

Carolina u. Baker, 485 U.S. 505 (1988); South Dakota

u. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987); Youngstown Sheet &

Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952); see also Free

Enter. Fund u. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Bd.,

561 U.S. 477, 491 & n.2 (2010) (ruling that

Appointments Clause claim was properly before the

courts, despite the absence of a statutory cause of

action); accord Bond, 131 S. Ct. a t 2363-2364 (“The

individual, in a proper case, can assert injury from

governmental action taken in excess of the authority

5 C harles A lan W right et al., Federal Practice and Procedure §

3566, a t 292 (3d ed. 2008).

15

th a t federalism defines.”); see also id. a t 2365 (“The

structural principles secured by the separation of

powers protect the individual as well.”).

C. The Suprem acy Clause As Well May

Be Enforced Through D irect

Equitable Actions.

Given the courts’ historical willingness to

entertain direct actions to enforce the Constitution, it

would be surprising to learn tha t the Supremacy

Clause, alone among the Constitution’s provisions,

could not be so enforced. As the Fram ers explained,

the Supremacy Clause is fundam ental to the

Constitution, for if the laws of the United States

“were not to be supreme,” then “they would amount

to nothing.” Federalist No. 33 (Hamilton). The

Supremacy Clause thus “flows immediately and

necessarily from the institution of a federal

government. Id.', see also Resp. Br. 13-15. In keeping

with historical tradition, direct actions under the

Supremacy Clause have played an im portant role in

vindicating the supremacy of federal law, as Osborn

and Ex parte Young illustrate.

This Court has implicitly recognized a right of

action under the Supremacy Clause to enjoin

preempted state law in many contexts—including

cases where the preempting federal law was enacted

pursuant to Congress’s Spending Clause powers, and

where state participation in the federal program was

voluntary .6 By routinely resolving such claims on the

6 See, e.g., A rkansas D ep’t o f H ealth & H um an Servs. v.

Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268 (2006) (federal M edicaid law preem pts

s ta te s ta tu te imposing liens on to rt se ttlem en t proceeds). In

Pharm . Research & Mfrs. o f Am erica v. Walsh, 538 U.S. 644

(2003) ( PhRM A ), seven Justices (four in the p lu rality and

16

merits, without regard to whether a federal statute

confers a right of action, this Court has established

not only th a t federal courts have subject-matter

jurisdiction over claims to enjoin preempted state

law, but also that there is a right of action under the

Supremacy Clause for such claims. It is particularly

noteworthy that the Court entertained such

Supremacy Clause claims without reference to a

statutory cause of action long before Maine v.

Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980), established that § 1983

may be used to vindicate federal statutory—in

addition to federal constitutional—rights against

state interference. See, e.g., Florida Lime & Avocado

Growers, Inc. v. Paul, 373 U.S. 132 (1963); Hines v.

Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52 (1941); Asakura v. City of

Seattle, 265 U.S. 332 (1924). That tradition continues

unbroken to this day .7

th ree in dissent) reached and resolved the m erits of p lain tiffs

claim th a t the challenged sta te law was preem pted by the

federal M edicaid sta tu te . See id. a t 649-670 (plurality opinion)

(finding on the m erits th a t s ta te law was not preem pted); id. a t

684 (O’Connor, J., concurring in p art and dissenting in part)

(finding on the m erits th a t the sta te law was preem pted). By so

doing, seven Justices im plicitly concluded both th a t the Court

h ad the au thority to resolve the case under federal-question

jurisdiction and th a t the p lain tiff had a claim to injunctive relief

u n d er the Suprem acy Clause. See id. a t 668 (plurality opinion).

7 See e.g., A rizona v. In ter Tribal Council o f Arizona, 133 S. Ct.

2247 (2013) (National V oter R egistration Act preem pts s ta te

s ta tu te requiring prospective voters to presen t evidence of

citizenship); Arizona v. United States, 132 S. Ct. 2492 (2012)

(Federal im m igration law preem pts m ultiple provisions of

Arizona SB 1070); Rowe v. New H am pshire Motor Transp.

A ss ’n, 552 U.S. 364 (2008) (Federal Aviation A dm inistration

A uthorization Act preem pts s ta te requirem ents re la ted to the

tran sp o rt of tobacco products); Ahlborn, 547 U.S. 268 (federal

M edicaid law preem pts s ta te s ta tu te imposing liens on to rt

17

In short, “the rule th a t there is an implied

right of action to enjoin state or local regulation that

is preempted by a federal statutory or constitutional

provision—and th a t such an action falls within

federal question jurisdiction—is well established.”

Hart & Wechsler’s The Federal Courts & The Federal

System 807 (Fallon et al. eds., 6th ed. 2009)

(collecting cases).

This Court’s decision in Golden State Transit

Corp. v. City of Los Angeles, 493 U.S. 103 (1989), is

consistent with this analysis. That decision makes

clear that § 1983 does not provide a home for all

preemption claims (but may be used only to vindicate

federal “rights”), see id. a t 107, but it nowhere

suggests tha t preemption claims may not be directly

asserted merely because § 1983 does not provide a

vehicle to do so. That the Supremacy Clause itself

“does not create rights enforceable under § 1983,” id.

(emphasis added), means only th a t certain

settlem ent proceeds); PhRM A, 538 U.S. a t 649-670 (plurality

opinion) (Medicaid Act did not p reem pt s ta te prescription-drug

rebate law); Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Reilly, 533 U.S. 525 (2001)

(Federal C igarette Labeling and A dvertising Act preem pts sta te

regulations on cigarette advertising); Crosby v. N ational

Foreign Trade Council, 530 U.S. 363 (2000) (federal B urm a

s ta tu te preem pts s ta te s ta tu te barrin g s ta te procurem ent from

companies th a t do business w ith Burm a); United States v.

Locke, 529 U.S. 89 (2000) (various federal s ta tu te s preem pt

sta te regulations concerning, inter alia, the design and

operation of oil tankers); Foster v. Love, 522 U.S. 67 (1997)

(federal election s ta tu te preem pts L ouisiana’s “open prim ary”

statu te); Shaw v. Delta A ir Lines, Inc., 463 U.S. 85 (1983)

(Employee R etirem ent Income Security Act preem pts portions

of s ta te benefits law); see also David Sloss, Constitutional

Remedies for Statutory Violations, 89 Iowa L. Rev. 355, 365-400

(2004) (canvassing th is C ourt’s case law on preem ption claims).

18

preemption claims may not be brought under § 1983,

not tha t such claims may not be brought at all.

Indeed, the dissent in Golden State Transit, which

would have denied the award of money damages

under § 1983, made tha t very point, explaining tha t

denying relief under § 1983 “would not leave the

company without a remedy” because “§ 1983 does not

provide the exclusive relief tha t the federal courts

have to offer,” and th a t the plaintiffs could seek an

injunction on preemption grounds. Id. at 119

(Kennedy, J., dissenting).8

While acknowledging tha t the federal courts

have previously entertained direct actions to enforce

the Constitution (including the Supremacy Clause),

Petitioner, as well as some of its amici, has suggested

that, where Congress has not provided a vehicle like

8 Section 1983 is not duplicative of the righ t of action for in

junctive re lief under the Suprem acy Clause. By enacting § 1983,

Congress expanded the kinds of s ta te action th a t private

litigan ts could challenge and the rem edies they could seek

beyond those available in su its directly under the Constitution.

T hat § 1983 has been an im portan t m echanism to secure

constitutional righ ts by providing dam ages rem edies aga inst

state and local officials does not m ean th a t § 1983 is the only

avenue through which unconstitu tional s ta te action can be

challenged.

Likewise, an injunction enforcing the Suprem acy Clause

preserves the param ount place of federal law in our

constitutional scheme w ithout providing the full range of

remedies, including dam ages, th a t m ight be available if

Congress authorized a direct cause of action under a federal

s ta tu te itself. For th a t reason, a direct cause of action under the

Suprem acy C lause does not “effect a complete end-run around

th is C ourt’s im plied righ t of action and 42 U.S.C. § 1983

jurisprudence.” Douglas v. Independent L iving Center o f S. Cal.,

132 S. Ct. 1204, 1213 (2012) (Roberts, J., dissenting).

19

§ 1983 for such claims to be heard, the federal courts

should entertain direct actions only when they are

brought to prevent the threatened, imminent

enforcement of an unconstitutional or preempted

state law against the plaintiff. See Pet. Br. 40;

National Governors Ass’n et al. Amicus Br. 25-27;

Texas et al. Amicus Br. 14-15; U.S. Amicus Br. 18-

21.9 Those suggestions should be rejected for several

reasons.

First, those argum ents are inconsistent with

this Court’s uniform precedent. This Court has heard

and sustained many direct equitable actions under

the Constitution, including the Supremacy Clause,

and also including preemption claims based on a

federal spending statute, even when there was no

evident enforcement action to which the federal

claim might be raised as a defense. For example, in

Crosby v. N a t’l Foreign Trade Council, 530 U.S. 363

(2000), the challenged M assachusetts law barred

government procurement of goods and services from

companies doing business with Burma. See id. at

366-367. There was no “enforcement” action in which

9 The U nited S ta tes has tak en the position elsew here th a t the

Suprem acy C lause provides a direct cause of action th a t is not

lim ited to asse rting a defense to a s ta te enforcem ent action.

See, e.g., Compl., United States v. Arizona, 10-cv-01413 (D. Ariz.

Ju ly 6, 2010) (filed by the U nited S ta tes as p lain tiff challenging

Arizona im m igration law, seeking declaratory and injunctive

relief and asse rting “Violation of the Suprem acy C lause” as its

first cause of action) (prelim inary injunction a ff’d in part and

rev’d in part, 132 S. Ct. 2492 (2012)); Compl., United States v.

Alabam a, ll-cv-02746 (N.D. Ala. Aug. 1, 2011) (sim ilar, in

challenge to A labam a law) (prelim inary injunction a f f’d in p a rt

and rev’d in part, 691 F.3d 1269 (11th Cir. 2012), cert, denied,

133 S. Ct. 2022 (2013)).

20

the companies could raise preemption as a defense;

the plaintiffs simply could no longer get government

contracts. This Court held tha t the state law was

preempted, necessarily presuming tha t there was a

right of action under the Supremacy Clause tha t

could be asserted directly and not merely in defense

of an enforcement action. Id. at 367.

Similarly, in Toll v. Moreno, 458 U.S. 1 (1982),

the Court considered a preemption challenge by a

group of non-citizen Maryland residents to a

University of Maryland policy tha t rendered the

plaintiffs ineligible for in-state tuition rates based on

their immigration classification. As in Crosby, the

plaintiffs were not subject to an enforcement action,

or a state regulation, forbidding them from certain

prim ary conduct. Instead, they were simply denied

an opportunity to apply for in-state tuition rates. The

Court nonetheless reached the m erits of the claim,

and found tha t “insofar as it bars domiciled G-4

aliens (and their dependents) from acquiring in-state

status, the University’s policy violates the

Supremacy Clause.” Id. at 17. See also Inter Tribal

Council, 133 S. Ct. 2247 (resolving National Voter

Registration Act-based preemption claim tha t was

raised affirmatively); PhRMA, 538 U.S. at 649-670

(plurality opinion); id. at 684 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring in part and dissenting in part) (seven

Justices resolving Medicaid-based preemption claim

th a t was raised affirmatively); supra pp. 11-12

(noting other examples of direct constitutional claims

being entertained where they could not have been

raised as defenses to enforcement actions).

Second, a rule barring many affirmative

preemption claims, while allowing claims based on a

21

violation of constitutional rights to go forward in

federal court under § 1983, would be extraordinarily

inefficient and would undermine the effective

vindication of federal law. Litigants frequently

pursue both preemption theories and other

constitutional claims. Cases before this Court teem

with examples: businesses commonly pursue both

preemption claims and claims under the Commerce,

Contracts, or Due Process Clauses; imm igrants

pursue both preemption claims and claims under the

Equal Protection Clause and First Amendment;

racial minorities pursue both statutory claims and

claims under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. Very often, courts tu rn to the

preemption claim first in order to avoid reaching

difficult constitutional questions. See, e.g., Crosby,

530 U.S. 363 (holding state procurement statu te

preempted by federal Burma statute, and thereby

avoiding dorm ant Foreign Commerce Clause claim);

Toll, 458 U.S. a t 9-10 (holding M aryland policy

preempted, and thereby avoiding Due Process and

Equal Protection claims); Hines, 312 U.S. 52 (holding

Pennsylvania registration law for non-citizens

preempted by federal legislation enacted while the

case was before the Supreme Court, and thus

avoiding Equal Protection claim).

If litigants could not pursue both preemption

claims (directly) and other constitutional claims

(under § 1983) in a single action for equitable relief,

then, in cases where a state forum was available for

their preemption claims, they would be forced either

to divide their federal claims between federal and

state courts (which could well be barred by rules

against splitting causes of action) or to forgo the

federal forum for their § 1983 claims (which would be

22

contrary to the strong congressional policy in favor of

affording a federal forum for such claims). See, e.g.,

Patsy v. Bd. of Regents of Fla., 457 U.S. 496 (1982).

The far more efficient and sensible rule, as well as

the one more consistent with this Court’s decisions,

is to allow equitable claims based on all provisions of

the Constitution, including the Supremacy Clause, to

be entertained in affirmative litigation through an

action directly under the Constitution.

The rule proposed by Petitioner and its amici

would have even more damaging results where there

is no state forum for litigants’ preemption claims.

Many Supremacy Clause claims cannot be raised

defensively at all, because there is no enforcement

action in which they can be raised. In such

circumstances, unless a state has decided to provide

an alternative forum, an affirmative direct action

under the Constitution is the only way in which the

supremacy of federal law could be established. See

David Sloss, Constitutional Remedies for Statutory

Violations, 89 Iowa L. Rev. 355, 406 (2004)

(discussing such claims). And, even when a litigant

might be able to assert his Supremacy Clause claim

in state court, his ability to establish the supremacy

of federal law should not be dependent on the venues

th a t state law happens to make available.

The history of the civil rights movement in

this country well illustrates the need to enforce

federal rights in the federal courts, without reliance

on legislative grace or the vagaries of state law. Had

§ 1983 never been enacted, it could hardly be the

case tha t state laws providing for segregated schools,

white primaries, and restrictions on immigrants

could have gone unchallenged. Plaintiffs could

23

challenge, and did challenge, such unconstitutional

state laws directly under the Constitution, including

the Supremacy Clause. And nothing in the

Supremacy Clause suggests th a t it may not also be

used directly to challenge state laws because they

conflict with a federal law, and not (or not just) the

federal Constitution. The Supremacy Clause itself

provides th a t both the Constitution “and the Laws of

the United States which shall be made in Pursuance

thereof . . . shall be the supreme Law of the Land.”

U.S. Const, art. VI (emphasis added).

Finally, nothing in the Supremacy Clause or

this Court’s precedent indicates th a t statu tes enacted

pursuant to Congress’s Spending Clause power

should be treated any differently than statutes

enacted pursuant to other sources of congressional

power, i.e., that direct causes of action may not be

brought to vindicate the federal structural interest in

the supremacy of Spending Clause statutes. Indeed,

numerous Spending Clause sta tu tes—including Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the

Education Amendments of 1972, and the Individuals

with Disabilities Education Act—are critical in

preventing discrimination and protecting civil

liberties, and many others—such as Medicaid and

the Supplemental N utrition Assistance Program

(previously called the Food Stamp Program)—

provide a critical safety net on which low-income

individuals and persons with disabilities rely for

survival.

24

II. PRECLUDING DIRECT RIGHTS OF

ACTION UNDER THE SUPREMACY

CLAUSE WILL HAVE BROAD AND

HARMFUL CONSEQUENCES FOR

MAINTAINING THE SUPREMACY OF

FEDERAL LAW.

An action under the Supremacy Clause

provides an im portant—and sometimes the only—

avenue to vindicate the supremacy of federal law.

Barring a right of action under the Supremacy

Clause could effectively foreclose this critical avenue

for persons, especially racial and ethnic minorities,

immigrants, persons with disabilities, and low-

income individuals, who depend on federal law and

who would otherwise be subject to invalid state and

local laws.

A. Racial and Ethnic M inorities,

Im m igrants, Persons With

D isab ilities, And Low-Income

Individuals Continue To D epend On

D irect A ctions Under The Suprem acy

Clause To Challenge Invalid State

And Local Laws.

Racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants,

persons with disabilities, and low-income individuals

continue to rely directly on the Supremacy Clause to

challenge invalid state and local laws in many

important areas, including immigration, fair

housing, public assistance, and health care. Many of

those cases have involved legislation enacted under

Congress’s Spending Clause power, and the courts

have routinely adjudicated and sometimes

invalidated state laws tha t conflicted with the

federal legislation.

25

For example, plaintiffs in recent years have

used the Supremacy Clause to challenge the

increasing number of state laws tha t seek to restrict

imm igrants’ rights, including im m igrants’

employment opportunities. In Chamber of Commerce

v. Edmondson, 594 F.3d 742 (10th Cir. 2010),

plaintiffs claimed th a t provisions of the Oklahoma

Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act of 2007, which

created new employee verification rules and imposed

sanctions on employers tha t allegedly hire

undocumented immigrants, conflicted with federal

immigration law, which sets forth a comprehensive

scheme prohibiting the employment of such

individuals. The Tenth Circuit, which upheld in part

a preliminary injunction against enforcement of the

state law, explained tha t a “party may bring a claim

under the Supremacy Clause tha t a local enactm ent

is preempted even if the federal law at issue does not

create a private right of action.” Id. a t 756 n.13

(internal quotation m arks omitted); see also Chamber

of Commerce v. Whiting, 131 S. Ct. 1968 (2011)

(adjudicating preemption challenge to Arizona law

providing for the revocation or suspension of licenses

in certain circumstances when state employers

knowingly hire undocumented immigrants, but

finding no preemption).

Numerous other courts similarly have

addressed preemption challenges, under the

Supremacy Clause, to state and local laws tha t affect

imm igrants’ access to housing or otherwise target

immigrant communities. See, e.g., Valle del Sol Inc.

v. Whiting, 732 F.3d 1006 (9th Cir. 2013), cert,

denied, 134 S. Ct. 1876 (Apr. 21, 2014) (sustaining

pastor’s preemption and due process challenges to

state statu te criminalizing provision of assistance to

26

unauthorized immigrants); Lozano v. City of

Hazleton, 724 F.3d 297, 313 (3d Cir. 2013), cert,

denied, 134 S. Ct. 1491 (Mar. 3, 2014) (finding

preemption of municipal housing and employment

regulations relating to immigrants); Villas at

Parkside Partners u. City of Farmers Branch, 726

F.3d 524 (5th Cir. 2013) (en banc), cert, denied, 134

S. Ct. 1491 (Mar. 3, 2014) (finding municipal housing

regulations relating to immigrants preempted);

United States v. South Carolina, 720 F.3d 518, 524-

26 (4th Cir. 2013) (addressing separate preemption

challenges to South Carolina immigration laws by

United States and private parties, finding private

plaintiffs had implied private right of action, and

upholding preliminary injunction); Ga. Latino

Alliance for Human Rights v. Governor of Ga., 691

F.3d 1250, 1261-1262 (11th Cir. 2012) (finding

implied private right of action to challenge Georgia’s

Illegal Immigration and Enforcement Act of 2011

under Supremacy Clause and upholding preliminary

injunction in part); League of United Latin Am.

Citizens v. Wilson, 997 F. Supp. 1244 (C.D. Cal. 1997)

(finding preempted most provisions of a state law

that, inter alia, restricted imm igrants’ access to

health care, social services, and education).

Low-income individuals have likewise invoked

the Supremacy Clause to ensure compliance with

federal housing laws. In Kemp v. Chicago Housing

Authority, No. 10-cv-3347, 2010 WL 2927417 (N.D.

111. July 21, 2010), a single mother of two argued that

municipal rules unlawfully allowed the Chicago

Housing Authority to term inate her public housing

assistance in circumstances other than those

specified and limited by the United States Housing

Act of 1937. Kemp sought to enjoin the local law as

27

preempted under the Supremacy Clause. Although

the court ultim ately did not grant relief because of

the Anti-Injunction Act, it concluded tha t the

Supremacy Clause “create [s] rights enforceable in

equity proceedings in federal court,” and tha t it could

therefore exercise jurisdiction over Kemp’s

preemption claim. Id. at *3 (internal quotation

marks omitted).

Persons receiving public assistance have also

invoked the Supremacy Clause to challenge state

laws tha t term inate medical or other benefits in

contravention of federal law. For example, in

Comacho v. Tex. Workforce Comm’n, 408 F.3d 229

(5th Cir. 2005), the court invalidated under the

Supremacy Clause state regulations tha t expanded

the circumstances, beyond those allowed by federal

law, under which Medicaid benefits could be cut off

for low-income adults receiving assistance under the

federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families

program.

And, in Lankford v. Sherman, 451 F.3d 496

(8th Cir. 2006), the Eighth Circuit relied directly on

the Supremacy Clause to preliminarily enjoin a

Missouri regulation th a t limited Medicaid coverage

of durable medical equipment, such as wheelchair

batteries, catheters, and suction pumps for

respiration, to certain populations, making most

Medicaid recipients with disabilities in Missouri

ineligible to receive such items even if medically

necessary. Id. at 511. The court found tha t the

regulation conflicted with Medicaid’s requirements

and goals, including its goals with respect to

community access for persons with disabilities, and

therefore was likely preempted under the Supremacy

28

Clause. Id. at 513 (holding that plaintiffs had

“established a likelihood of success on the m erits of

their preemption claim” for obtaining a preliminary

injunction).

Direct actions under the Supremacy Clause,

therefore, rem ain critically im portant to racial and

ethnic minorities, immigrants, persons with

disabilities, and low-income persons in our society

who rely on them for vindication of federal law. The

availability of tha t direct action ensures tha t state

and local governments cannot undermine federal law

by enacting statutes and regulations that deviate

from federal requirements but would, absent a

Supremacy Clause action, be effectively insulated

from judicial review.

B. Precluding R ights Of A ction Under

The Suprem acy Clause Would

Underm ine Im portant Federal

Interests.

Precluding a right of action under the

Supremacy Clause would leave im portant rights and

interests effectively unprotected. Not only would the

rights of individual litigants seeking to invalidate

unconstitutional state laws be harmed, but

im portant federal supremacy interests could go

unprotected as well.

First, precluding rights of action under the

Supremacy Clause would leave few, if any, effective

remedies to force state compliance with many federal

laws th a t are intended to benefit racial and ethnic

minorities, immigrants, persons with disabilities,

and low-income persons in our society. In the context

of laws enacted under Congress’s Spending Clause

29

power, the term ination of federal funding may

sometimes be theoretically available to remedy the

S tate’s failure to comply with its obligations under

the Medicaid Act or other Spending Clause laws, see

PhRMA, 538 U.S. a t 675 (Scalia, J., concurring in the

judgment), but th a t remedy is so rare and drastic as

to be effectively unavailable as a meaningful

enforcement tool. As commentators have explained,

both political considerations and procedural hurdles

make withdrawal of federal funding an illusory

remedy. See, e.g., Bradford C. Mank, Suing Under §

1983: The Future After Gonzaga University v. Doe,

39 Hous. L. Reu. 1417, 1431-1432 (2003) (“[A]s a

practical m atter, federal agencies rarely invoke the

draconian remedy of term inating funding to a state

found to have violated the [federal] conditions

because there are often lengthy procedural hurdles

th a t allow a state to challenge any proposed

term ination of funding, and members of Congress

from tha t state will usually oppose term ination of

funding.”); Jane Perkins, Medicaid: Past Successes

and Future Challenges, 12 Health Matrix 7, 32

(2002) (“[T]he Medicaid Act provides for the Federal

Medicaid oversight agency to withdraw federal

funding if a State is not complying with the approved

State Medicaid plan; however, . . . this is a harsh

remedy th a t has rarely, if ever, been followed

through to its conclusion.”); Lisa E. Key, Private

Enforcement of Federal Funding Conditions Under §

1983: The Supreme Court’s Failure to Adhere to the

Doctrine of Separation of Powers, 29 U.C. Davis L.

Reu. 283, 292-93 (1996) (“[OJften the agency’s only

enforcement mechanism is a cutoff of federal funds

for the program [,] . . . [which] is rarely, if ever,

invoked.”).

30

Moreover, term ination of federal funding

would, in many circumstances, be counterproductive

and contrary to Congress’s intent tha t the funding

program be implemented to provide a wide benefit.

Indeed, persons who receive crucial benefits and

services from federal programs usually do not want

federal funding to be term inated. Terminating

federal funding would not protect the interests of

those injured by the S tate’s noncompliance with

federal law; rather, it would harm the very people

Congress intended to benefit. See Cannon v. Univ. of

Chi., 441 U.S. 677, 704-705 (1979) (explaining that

“term ination of federal financial support for

institutions engaged in discriminatory practices . . .

is . . . severe” and “may not provide an appropriate

means of accomplishing” the purposes of the statute);

see also Roderick M. Hills, Jr., Dissecting the State:

The Use of Federal Law to Free State and Local

Officials from State Legislatures’ Control, 97 Mich. L.

Rev. 1201, 1227-1228 (1999) (“[T]he sanction of

withdrawing federal funds from noncomplying state

or local officials is usually too drastic for the federal

government to use with any frequency: withdrawal of

funds will injure the very clients that the federal

government wishes to serve.”).

The more effective way to vindicate the

objectives of federal law is to allow private parties to

continue to play an im portant role in enforcing the

supremacy of federal statutes. As the United States

previously argued, “those programs in which the

drastic measure of withholding all or a major portion

of federal funding is the only available remedy would

be generally less effective than a system that also

permits awards of injunctive relief in private actions

in appropriate circumstances.” See U.S. Cert. Amicus

31

Br., Douglas v. Independent Living Ctr. of S. Cal.,

No. 09-958, at 19. In such circumstances, an

injunction would force a State to comply with the

federal provision at issue without harm ing the

intended beneficiaries of the federal pro-gram.

Nor would it be appropriate to force

individuals who depend on federal law to rely

exclusively on the federal government to bring

affirmative litigation to enforce compliance with the

Supremacy Clause. Private rights of action are

necessary because the government lacks the

resources to police preemption disputes between

States and private parties. See Sloss, supra, at 404.

Private rights of action “increase the social resources

devoted to law enforcement, thus complementing

government enforcement efforts.” Matthew C.

Stephenson, Public Regulation of Private

Enforcement: The Case for Expanding the Role of

Administrative Agencies, 91 Va. L. Ren 93, 108

(2005); see also Ahlborn, 547 U.S. a t 291.

The recent cases challenging state and local

immigration laws illustrate the importance of private

rights of action. A wave of state and local

immigration legislation began in 2006 and continued

through approximately 2011. Private plaintiffs—

individual immigrants, community organizations,

and businesses—began challenging the laws

immediately on preemption and other grounds. See,

e.g., Lozano (case initiated in 2006); Whiting (case

initiated in 2007). The federal government largely

agreed with the private plaintiffs’ claims tha t the

laws were preempted, and generally filed appellate

amicus briefs (and a m erits amicus brief in the

Supreme Court) in support of the cases tha t reached

32

those levels. See, e.g., U.S. Cert. Amicus Br., Villas at

Parkside Partners (5th Cir. No. 10-10751); U.S.

Amicus Br., Whiting (No. 09-115). But the United

States did not begin filing challenges on its own

behalf until 2010, and then only against a minority of

the preempted laws, and only in instances where

private plaintiffs had already filed suit.10 Absent a

right of action under the Supremacy Clause, there

could well have been no meaningful remedy at all to

invalidate many state and local laws tha t the courts

found to be unconstitutional.

A private right of action under the Supremacy

Clause serves other im portant values as well. The

Supremacy Clause supports the structural guarantee

of federalism—namely, tha t federal law will rem ain

paramount. And th a t interest can only be effectively

vindicated by ensuring tha t preempted state laws are

invalidated—a goal that, for the reasons described

above, can best be achieved through a private right of

action.11 In addition, by allowing robust enforcement

10 The U nited S ta tes filed actions challenging s ta te laws

enacted in Arizona, South Carolina, U tah, and A labam a. Unlike

private plaintiffs, the U nited S ta tes did not directly challenge

any local im m igration laws, s ta te laws in Georgia and Indiana,

or A rizona’s im m igrant em ploym ent law.

11 For example, preem ption claim s in im m igration and other

a reas of law have been critical to preserving the federal

governm ent's param ount role in foreign policy. See, e.g., Hines,

312 U.S. a t 63 (“O ur system of governm ent is such th a t the

in te rest of the cities, counties and states, no less th an the

in te re st of the people of the whole nation, im peratively requires

th a t federal power in the field affecting foreign relations be left

entirely free from local in terference.”); id. a t 66-67; see also Toll,

458 U.S. 1, 10-13(1982).

33

for preemption claims, a private right of action

fosters uniformity and predictability in the

application of both federal and state law. In order to

realize the Constitution’s fundam ental promise th a t

federal law will rem ain param ount over invalid state

and local laws, it is essential for this Court to

continue—as it has done for nearly two hundred

years—to allow litigants to bring preemption

challenges directly under the Supremacy Clause.

CONCLUSION

The judgm ent of the court of appeals should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Steven R. Shapiro

Counsel of Record

Omar C. Jadw at

A m e r ic a n C iv il L i b e r t i e s

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

sshapiro@aclu.org

Sherrilyn Ifill

Janai S. Nelson

Christina A. Swarns

Jin Hee Lee

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

34

mailto:sshapiro@aclu.org

Nina Perales

M e x ic a n A m e r ic a n L e g a l

D e f e n s e & E d u c a t io n a l

F u n d , I n c .

110 Broadway, Suite 300

San Antonio, TX 78205

Jon Greenbaum

L a w y e r s ’ C o m m it t e e f o r

C iv il R ig h t s U n d e r L a w

1401 New York Avenue,

NW, Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

Dated: December 22, 2014

35

RECORD PRESS, INC.