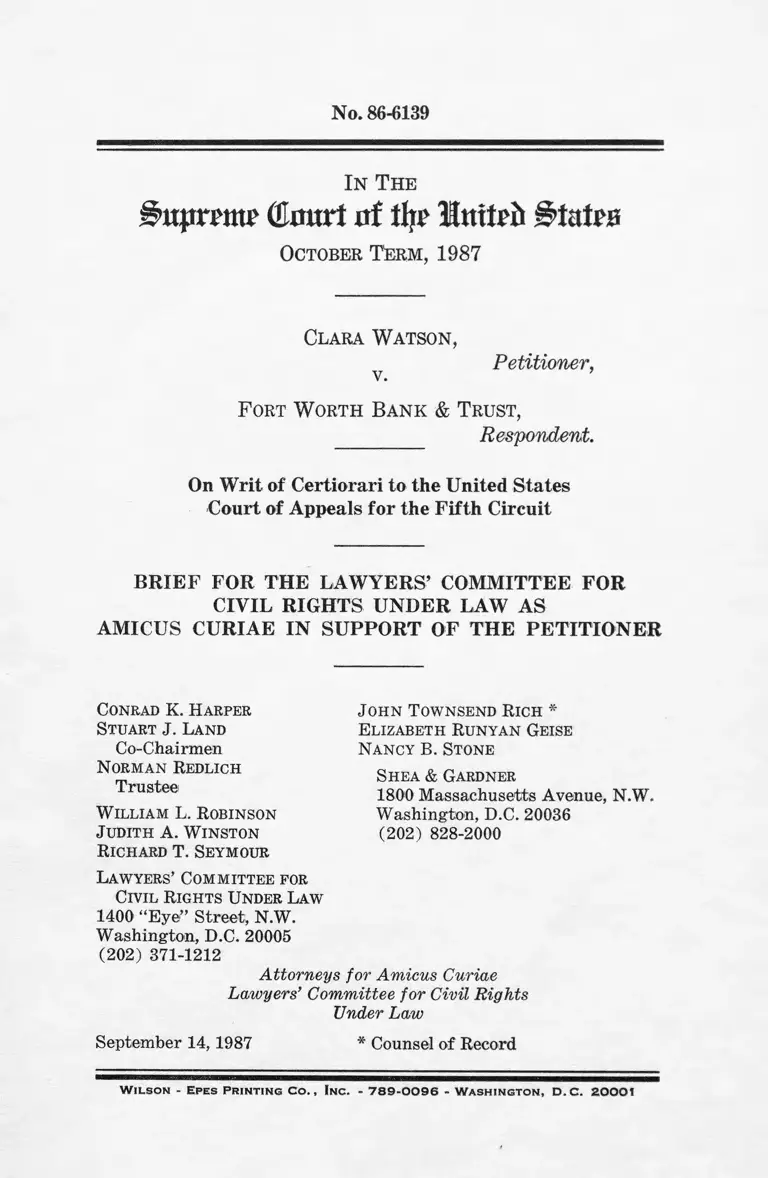

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

September 14, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioner, 1987. 76a7e2b5-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/952e3798-14ec-4b29-afa5-7c5b323946c4/watson-v-fort-worth-bank-and-trust-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-the-petitioner. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

No. 86-6139

I n T h e

(Cmirt of % llnttrh

Octo ber T e r m , 1987

Cl a r a W a t s o n ,

Petitioner,v.

F ort W o r th B a n k & T r u st ,

_________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONER

Conkad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Richard T. Seymour

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 “ Eye” Street, N W .

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

September 14,1987 * Counsel of Record

John Townsend Rich *

Elizabeth Runyan Geise

Nancy B. Stone

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, NW .

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

W il s o n - E p e s P r in t in g C o . , Inc. - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 J

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICUS C U R IA E ___________________ 1

SUMMARY OF A R G U M E N T _________________________ 2

A R G U M E N T ____________________________________________ 3

I. The Issue Presented by This Case Is Not Con

trolled by the Prior Opinions of This Court in

McDonnell Douglas, Teamsters, Hazelwood, or

Furnco ___________________________________________ 3

II. Subjective Employment Practices Should Not

Be Exempt From Disparate Impact Analysis- 8

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES________________________ ii

A. The Language of Title VII and Case Law

Thereunder, the Administrative Regulations,

and the Legislative History of the 1972

Amendments Demonstrate That No Ex

emption From Disparate Impact Analysis

for Subjective Employment Practices Is

Warranted____________________________________ _ 8

B. Relegating Plaintiffs Who Challenge Subjec

tive Employment Practices to Disparate

Treatment Analysis Would Defeat a Central

Purpose of Title V I I _________________________ 10

C. Allowing Disparate Impact Challenges to

Subjective Employment Practices Will Not

Leave an Employer Without a Defense to a

Disparate Impact Showing___________________ 22

CONCLUSION __________________________________________ 26

11

Cases:

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1 9 7 5 )------------------------------------------------------------9 ,19 ,2 1 , 23

Association Against Discrimination in Employ

ment, Inc. V. City of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256

(2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 988

(1 9 8 2 ) ------------------------------------------------------------------- 21

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477

(9th Cir. 1987) (en bane)_________________ 7 ,10 ,1 5 , 22

Baxter V. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495

F.2d 437 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1033

(1974) ------------------------------------------------------------------ 18

Bazemore v. Friday, 106 S. Ct. 3000 (1986) __1 4 ,15,18

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 ( 1 9 7 7 )_______ 13

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) __ 23

Chandler V. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976)____ 2

Coe v. Yellow Freight System, 646 F.2d 444 (10th

Cir. 1 9 8 1 )________________________________________ 19

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1 9 8 2 )_________ passim

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank, 467 U S. 867

(1 9 8 4 ) ------------------------------------------------------------------- 11,12

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345

(1983) ------------------------------------------------------------------ 2

Davis V. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1979) __ 12

Diaz v. American Telephone & Telegraph, 752: F.2d

1356 (9th Cir. 198 5)_____________________________ 12

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) _19, 20, 21, 23

Franks v. Bowman Transportation. Co., 424 U S.

747 (1 9 7 6 )_______________________________________ 18

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U S

567 (1 9 7 8 ) --------------------------------------------------------- 2, 4, 6, 7

Gilbert V. City of Little Rock, 722 F.2d 1390 (8th

Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 466 U.S. 972 (1984) __ 20

Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d 1516 (11th Cir. 1985) _ 16,19,

20 , 22

Griggs V. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ..passim,

Harris v. Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609 (8th Cir.

1 9 8 1 ) -------------------------------------------------------------------- 15

Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States, 433 U.S,

299 (1 9 7 7 )---------------------------------------------------------- passim

Ill

Johnson V. Transportation Agency, 107 S. Ct. 1442

(1 9 8 7 )____________________________________________ 13

Latinos Unidos de Chelsea en Aecion (Lucha) V.

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development,

799 F.2d 774 (1st Cir. 1986) ____________________ 16

Lewis V. Bloomsburg Mills, Inc., 773 F.2d 561

(4th Cir. 1 9 8 5 )__________________________________ 2, 16

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1 9 7 3 ) ------------------------------------------------------------------- passim

Meritor Savings Bank V. Vinson, 106 S. Ct. 2399

(1986) ______________________________________________ 9

Miles V. M.N.C. Corp,, 750 F.2d 867 (11th Cir.

1985) _____________________________________________ 22

Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136 (1977)__ 23

New York Transit Authority v. Beazer, 440 U.S.

568 (1 97 9 )_______________________________________ 23

O’Brien V. Sky Chefs, Inc., 670 F.2d 864 (9th Cir.

1982), overruled on other grotmds, Atonio V.

Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477 (9th

Cir. 1987) (en banc)_____________________________ 14

Paxton v. Union Nat’l Bank, 688 F.2d 552 (8th

Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 460 U.S. 1083 (1983) __ 17

Payne V. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d 798

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982)__ 2

Rowe V. Cleveland Pneumatic Co., 690 F.2d 88

(6th Cir. 1982) _________________________________ 22

Rowe V. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1 9 7 2 )________________________________________ 22, 24

Segar V. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984),

cert, denied sub nom. Meese V. Segar, 471 U.S.

1115 (1 9 8 5 )----------------------------------------------------------passim

Sledge V. J.P. Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625 (4th

Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 440 U.S. 981 (1979)_____2,21

Spurlock V. United Airlines, Inc., 475 F.2d 216

(10th Cir. 197 2)__________________________________ 23

Stewart V. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445

(7th Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 433 U.S. 919

(1977) _____________________________________________ 21,24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES*— Continued

Page

IV

Teamsters V. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) -passim

Texas Dep’t of Community Affairs V. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1 9 8 1 )--------------------------------------------------- 16,18

Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094 (D.G. Cir. 1983),

vacated on other grounds, 465 U.S. 1056

(1 9 8 4 ) ------------------------------------------------------------------- 18

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

652 ( 2d Cir. 1 9 7 1 )_______________________________ 10

Vuyanich V. Republic Nat’l Bank of Dallas, 521

F. Supp. 656 (N.D. Tex. 1981), vacated on other

grounds, 723 F.2d 1195 (5th C'ir.), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 1073 (1984) ___________________________16, 17

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)________ 8, 21

Statutes, Regulations and Rule:

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended:

§ 703(a) (2), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (a) (2)

(1 9 8 2 )----------------------------------------------------------- 4 , 5 , 8

§ 7 0 7 (d )-(e ), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6(d) to -(e)

(1 9 8 2 ) ----------------------------------------------------------- 11

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures :

29 C.F.R. § 1607.1 (A ) (1986)__________________ 9

29 G.F.R. § 1607.3 (A) (1986)__________________ 9

29 C.F.R. § 1607.6(B) (1) & (2) (1986)._______ 24

29 C.F.R. § 1607.16 (q) (1986)_________________ 9

Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States,

Rule 3 6 .2 _________________________________________ 1

Other Authorities:

Adoption of Questions and Answers To Clarify

and Provide a Common Interpretation of the

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Pro

cedures, 44 Fed. Reg. 11996 (March 2, 1979) __ 24

D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of Discrimi

nation (1980 & Supp. 1986)_____________________ 14,19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Bartholet, Application of Title VII to- Jobs in High

Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947 (1 98 2 )____________ 16, 25

B. Schlei & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimina

tion Law (1 9 8 3 )________________________________ 14, 23

C. Sullivan, M. Zimmer, R. Richards, Federal Stat

utory Law of Employment Discrimination

(1980) ____________________________________________ 7

I n T h e

wpnm (final rtf llp> luttrit States

Octo ber T e r m , 1987

No. 86-6139

Cl a r a W a t s o n ,

Petitioner, v. ’

F ort W o rth B a n k & T ru st ,

_________ Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONER

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

submits this brief as amicus curiae, urging reversal.1

The Lawyers’ Committee is a nonprofit organization

established in 1963 at the request of the President of the

United States to involve leading members of the bar

throughout the country in the national effort to insure

civil rights to all Americans. It has represented and

assisted other lawyers in representing numerous individ

uals in administrative proceedings and lawsuits under

1 Pursuant to Rule 36.2, the Lawyers’ Committee has filed written

consents of the parties to the submission of this brief as amicus

curiae.

2

Title VII. E.g., Lewis v. Bloomsburg Mills, Inc., 773

F.2d 561 (4th Cir. 1985); Payne v. Travenol Labora

tories, Inc., 673 F.2d 798 (5th Cir. 1982); Sledge v. J.P.

Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625 (4th Cir. 1978). The Law

yers’ Committee has also represented parties and partici

pated as an amicus in Title VII cases before this Court.

E.g., Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976);

Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345 (1983);

Hazelwood School Disk v. United States, 433 U.S. 299

(1977).

The question presented by this case— whether disparate

impact analysis may be applied to employment practices

involving subjective decisionmaking— is an important

and recurring issue of Title VII law. This Court’s deci

sion will undoubtedly have significant implications for

present and future Title VII suits in which the Lawyers’

Committee participates. In addition, the Lawyers’ Com

mittee’s experience in Title VII litigation may enable it

to illuminate some of the issues presented by this case for

this Court.

SUM M ARY OF ARGUMENT

The issue before this Court is a narrow one: whether

the court of appeals was correct to preclude disparate

impact analysis of the respondent bank’s promotion prac

tices on the grounds that such practices were “ discretion

ary,” i.e., involving subjective decisionmaking. Contrary

to the position of amicus United States, this issue is not

controlled by this Court’s prior decisions in McDonnell

Douglas Cory. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), Hazelwood School

Disk v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), and Furnco

Construction Cory. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567 (1978).

While this Court declined to apply disparate impact

analysis in each of those cases, it did so either because

the only claims at issue were of intentional discrimina

tion or because the evidence presented did not support a

disparate impact claim. Thus, this case presents an issue

not yet considered by this Court.

3

On the merits, the language of Title VII and the case

law thereunder, the administrative regulations, and the

legislative history of the 1972 amendments all demon

strate that no exemption from disparate impact analysis

for subjective employment practices is warranted. Fur

thermore, the differences between a disparate treatment

and disparate impact challenge to a subjective employ

ment practice— which we explain in detail— show that to

confine such challenges to disparate treatment analysis

would defeat a central purpose of Title VII, i.e., to get

rid of employment practices with an adverse impact on

suspect groups that are not justified as “ job-related” or

by “business necessity” , whatever the motivation behind

the practices. Finally, contrary to the contention of

amicus United States, allowing disparate impact chal

lenges to subjective practices will not leave an employer

without a defense to a disparate impact showing. A

“ business necessity” or “ job-related” defense would still

be possible, and certain subjective practices may be ca

pable of validation.

ARGUMENT

I. The Issue Presented by This Case Is Not Controlled

by the Prior Opinions of This Court in McDonnell

Douglas, Teamsters, Hazelwood, or Furnco.

The evidence below established that respondent bank’s

practice was to allow promotion decisions to rest in the

discretion of “ a limited group of white department

supervisors.” Pet. App. 7a. The court of appeals held

that the petitioner could not attempt to show that such

a promotion policy was unlawfully discriminatory under

disparate impact analysis because the promotion policy

was “ discretionary.” Pet. App. 8a. In Connecticut v.

Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 445-446, 448 (1982), this Court noted

that disparate impact analysis, first outlined in Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), is based on

4

Section 703(a) (2) of Title VII,’2 and that Griggs and its

progeny stand for the proposition that an employment

practice which has a disparate impact on a suspect group

and is not shown to be related to job performance is

illegal, whether or not the employer had an “ invidious

intent” in adopting such a practice. Id. at 446. Dispar

ate treatment analysis, by contrast, seeks to outlaw in

tentional discrimination in employment, on either an

individual or class-wide basis. Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 335-36 & n.15 (1977). This Court

has emphasized that a given employment practice may

be attacked under both disparate impact and disparate

treatment theories. Id. at 336 n.15. Thus, the issue

before this Court is whether the Fifth Circuit correctly

precluded the plaintiff from proceeding under disparate

impact theory on the grounds that the employment prac

tice she challenged was “ discretionary.”

In its amicus brief on petition for writ of certiorari,

the United States suggested that this Court has already

decided this issue in four prior decisions, McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), Hazelwood

School Dist. v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), and

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S.' 567

(1978). According to the United States, all four cases

involved attacks on “ subjective selection devices,” and,

in each case, this Court “ declined to extend the disparate

2 Section 703(a) (2 ), 42 U.S.C. :§ 2000e-2(a) (2) (1982), provides

in the pertinent part as follows:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an em

ployer—

“ (2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or appli

cants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend

to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or

otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because

of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin.”

5

impact doctrine * * * [and] instead * * * required

Title VII plaintiffs to prove discriminatory motivation.”

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae in Support

of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, at 11 (May 1987)

(hereinafter “ U.S. Cert. Brief” ). Contrary to the

United States’ position, however, examination of those

four cases reveals that none decided the precise issue

presented here.

In three of the four cases cited by the United States

in its brief on certiorari, McDonnell Douglas, Teamsters,

and Hazelwood, the only claims presented were of in

tentional racial discrimination; no claims of disparate

impact under § 703(a) (2) of Title VII were made.

Thus, in McDonnell Douglas, plaintiff’s claim was that

the employer defendant “ had refused to rehire him be

cause of his race and persistent involvement in the civil

rights movement, in violation of §§ 703 (a )(1 ) and

704(a) [of Title V II].” 411 U.S. at 796. Similarly,

Teamsters and Hazelwood both involved claims that the

employer had engaged in a “ pattern or practice” of in

tentional discrimination. See Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S.

at 335 ( “ The Government’s theory of discrimination

was simply that the company, in violation of § 703(a)

of Title VII, regularly and purposefully treated Negroes

and Spanish-surnamed Americans less favorably than

white persons.” ) ; Hazelwood, supra, 433 U.S. at 307

n .ll (as in Teamsters, the government’s claim was that

the employer “ ‘regularly and purposefully treated Ne

groes . . . less favorably than white persons’ ” ). Thus,

given that the only claim asserted in each of the three

cases was intentional discrimination, each was properly

analyzed under disparate treatment theory, and dispar

ate impact analysis was not implicated.

The United States cites language from McDonnell

Douglas where this Court drew a distinction between the

plaintiff’s claim of a discriminatory refusal to rehire

him, and an exclusion from employment, as in Griggs,

6

“ on the basis of a testing device which overstates what

is necessary for competent performance, or through some

sweeping disqualification of all those with any past rec

ord of unlawful behavior * * U.S. Cert. Brief at 12,

citing 411 U.S. at 806. But the point of this distinction

was not, as the U.S. suggests, to draw a line between

“ objective” employment practices, to which a Griggs

analysis applies, and “ subjective” practices, to which

Griggs is inapplicable. Instead, the Court’s point was

that the Griggs disparate impact analysis is designed to

challenge “ systemic results of employment practices.”

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249, 1267 (D.C. Cir. 1984).

Thus, because the plaintiff in McDonnell Douglas claimed

only that he was the victim of an intentionally discrimi

natory employment decision unique to him, rather than

any sort of broader policy or system of the employer,

disparate impact analysis did not apply.

In contrast to McDonnell Douglas, Teamsters and

Hazelivood, the plaintiffs in Furnco sought to proceed

under both disparate impact and disparate treatment

analysis. 438 U.S. at 569. The case involved the hiring

of bricklayers by a superintendent at a construction site.

The challenged practice was the superintendent’s refusal

to accept applications for bricklayer positions at the job

site; instead, the superintendent “ hired only persons

whom he knew to be experienced and competent * * * or

persons who had been recommended to him as similarly

skilled.” 438 U.S. at 570. Although this Court held that

the “proper approach” for this claim was the disparate

treatment model set forth in McDonnell Douglas, 438

U.S. at 575, the reason for this conclusion was not that

a “ subjective” employment practice was involved. The

district court in Furnco had held that plaintiffs had not

shown that Furnco’s policy of not hiring at the gate

“had a disproportionate impact or effect on black brick

layers,” 438 U.S. at 571, and this finding had not been

found to be erroneous by the court of appeals. Id. at

7

570. Thus, when this Court concluded that plaintiffs’

claims were properly analyzed under the model set forth

in McDonnell Douglas, it was simply affirming the dis

trict court’s and court of appeals’ holdings that there

was insufficient evidence to make out a disparate impact

claim.3 In these circumstances, this Court did not have

to reach the issue presented here, i.e., whether the type

of “ discretionary” or “ subjective” employment practice

at issue in Furnco could he subject to disparate impact

analysis.4

In sum, the narrow issue presented by this case—

whether disparate impact analysis may be applied to

subjective employment practices— has never been decided

by this Court. And, as we discuss below, there is no

basis for an exception to disparate impact analysis when

the employment practice challenged involves subjective

decisionmaking.

3 Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477, 1484 (9th

Cir. 1987) (en banc) (disparate impact analysis was inapplicable

in Furnco because plaintiffs “failed to establish a prima facie case

of disparate impact” ) ; C. Sullivan, M. Zimmer, R. Richards, Fed

eral Statutory Law of Employment Discrimination § 1.6, at 67

(1980) ( “ better construction” of Furnco is that “disparate impact

analysis was available but there was no showing of impact” ) .

4 The United States suggests that, like the plaintiffs in Furnco,

petitioner’s evidence would not make out a prima facie case of

disparate impact. See U.S. Cert. Brief at 20 n.16. Nevertheless,

petitioner is in a different position before this Court than the

plaintiffs in Furnco-, rather than evaluating her statistical evidence

and holding that a prima facie case of disparate impact was not

presented, the lower courts in this case simply precluded petitioner

from proceeding on a disparate impact basis.

8

II. Subjective Employment Practices Should Not Be Ex

empt From Disparate Impact Analysis.

A. The Language of Title VII and Case Law There

under, the Administrative Regulations, and the

Legislative History of the 1972 Amendments Dem

onstrate That No Exemption From Disparate Im

pact Analysis for Subjective Employment Practices

Is Warranted.

Examination of the language of Title VII, the rele

vant case law, the administrative regulations, and the

legislative history of the 1972 amendments demonstrates

that no exception to disparate impact analysis for em

ployment practices involving subjective decisionmaking

is justified.5

In Connecticut v. Teal, supra, 457 U.S. at 445-46, 448,

this Court held that disparate impact analysis is founded

upon Section 703(a) (2) of Title VII. That section pro

hibits “ employment practice[s] ” which “ limit, segregate,

or classify” employees or applicants because of “ race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.” See p. 4, n.2,

supra. Thus, as noted in Teal, supra, 457 U.S. at 448,

“ [t]he statute speaks * * * in terms of limitations and

classifications that would deprive any individual of em

ployment opportunities.” (Emphasis in original.) This

language does not suggest an exemption for employment

“practices,” “ limitations,” or “ classifications” which in

volve or result from subjective decisionmaking. Further,

this Court’s decisions have broadly stated that employ

ment “ practices” or “ procedures” may be subject to

disparate impact analysis, without carving out any ex

ception for practices or procedures that involve sub

jective decisionmaking. E.g., Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

430 (disparate impact analysis reaches employment

“practices, procedures, or tests” ) ; Washington v. Davis,

B For a more detailed analysis of these points, see the brief for

amicus curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

9

426 U.S. 229, 246-47 (1976) (disparate impact analysis

available to challenge “hiring and promotion practices” ).

The administrative regulations under Title VII also

provide support for the point that employment practices

involving subjective decisionmaking should not be exempt

from disparate impact analysis. Those regulations

( “ Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures” ) define the selection procedures to which dispar

ate impact analysis may be applied as ranging from the

objective “ traditional paper and pencil tests” to the

clearly subjective “ informal or casual interviews and

unscored application forms.” 29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.3(A),

1607.16 (q) (1986). Because these regulations were

promulgated by the four federal agencies responsible for

enforcing Title VII,6 this Court has noted that they are

entitled to “ great deference” as the enforcing agencies’

“ administrative interpretation of the Act.” Griggs,

supra, 401 U.S. at 433-34; Albemarle Paper Co. V.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 431 (1975). See also Meritor Sav

ings Bank v. Vinson, 106 S. Ct. 2399, 2405 (1986)

(while not controlling, EEOC guidelines “ ‘constitute a

body of experience and informed judgment to which

courts and litigants may properly resort for guid

ance’ ” ).

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to

Title VII similarly indicates that no exception to dis

parate impact analysis for employment practices involv

ing subjective decisionmaking is warranted. In Con

necticut v. Teal, supra, 457 U.S. at 449, this Court noted

that the legislative history to the 1972 amendments

showed that Congress intended to remove for state and

municipal employees the same sort of “ discriminatory

barriers” to equal employment opportunity that the

6 These agencies are the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, the Civil Service Commission, the Department of Labor,

and the Department o f Justice. 29 C.F.B. § 1607.1(A) (1986).

10

Griggs disparate impact analysis had removed for pri

vate sector employees; examples of such “barriers” iden

tified by Congress included “promotions made on the

basis of * * * ‘discriminatory supervisory ratings.’ ” Id.

at 449 n.10. Thus, Congress clearly anticipated that dis

parate impact theory could be applied to such subjective

employment practices. Moreover, the legislative history

of the 1972 amendments shows that Congress meant, in

areas where a contrary intention was not expressed, to

endorse the existing Title VII case law. Id. at 447 n.8.

And, at the time of the 1972 amendments, courts of ap

peals had applied disparate impact analysis to employ

ment practices involving subjective decisionmaking. See

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477, 1482-

83 (9th Cir. 1987) (en banc) (citing United States v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652, 657-58 (2d Cir.

1971)).

In sum, the language of Title VII, the case law, the

administrative regulations, and the legislative history of

the 1972 amendments all indicate that subjective em

ployment practices should be subject to disparate impact

analysis. Moreover, as we show below, creating an ex

ception to disparate impact analysis for subjective em

ployment practices would defeat a central purpose of

Title VII.

B. Relegating Plaintiffs Who Challenge Subjective

Employment Practices to Disparate Treatment

Analysis Would Defeat a Central Purpose of Title

VII.

If this Court affirms, plaintiffs challenging subjective

employment practices as illegally discriminatory will be

confined to disparate treatment analysis. When a plain

tiff is challenging one employment decision unique to

him, as in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra? 7

7 In McDonnell Douglas, the plaintiff challenged the employer’s

failure to rehire him after his participation in various civil rights

11

confining that plaintiff to disparate treatment analysis

would not make a difference. A case that involves one

unique employment decision is not the sort where a

disparate impact claim could be made out. But where a

plaintiff is challenging a pattern or a series of subjective

employment decisions, relegating that plaintiff to dis

parate treatment analysis would be significant. There

are important differences between disparate treatment

and disparate impact analysis in that situation. Be

cause of these differences, confining attacks on a pattern

or series of subjective employment decisions to disparate

treatment analysis would defeat a central purpose of

Title VII identified in Griggs— to get rid of employment

practices with an adverse impact on suspect groups that

are not justified by business necessity, whatever the

motivation behind the practices.

The aim of disparate treatment analysis is to discover

whether there has been intentional discrimination in vio

lation of Title VII. “ Proof of discriminatory motive is

critical * * *.” Teamsters v. United States, supra, 431

U.S. at 335 n.15. Given this ultimate issue, a disparate

treatment challenge to a pattern or series of employ

ment practices involving subjective decisionmaking would

proceed as follows.8

demonstrations against the employer’s allegedly racist hiring pol

icies. The plaintiff did not challenge any broad policy or practice

of the employer concerning the rehiring of former employees, just

one employment decision affecting him. 411 U.S. at 796.

8 Disparate treatment challenges to a pattern or series of em

ployment decisions generally proceed as “pattern or practice” ac

tions. In a “pattern or practice” case, the allegation is that the

employer “ regularly and purposefully” discriminated, i.e., that “dis

crimination was the company’s standard operating procedure1—the

regular rather than the unusual practice.” Teamsters V. United,

States, supra, 431 U.S. at 335-36; Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank,

467 U.S. 867, 876 (1984). While pattern or practice suits are

brought either by the EEOC, pursuant to § 707(d )-(e ) of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. §2000e-6(d) to -(e ) (1982), or as private class actions,

12

As an initial matter, a plaintiff making a disparate

treatment claim must present a prima facie case of in

tentional discrimination, i.e., the “plaintiff must carry the

initial burden of offering evidence adequate to create an

inference that an employment decision was based on a

discriminatory criterion illegal under [Title V II].”

Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 358. In McDonnell Doug

las, supra, 411 U.S. at 802, this Court outlined one for

mulation of how a plaintiff could go about establishing a

prima facie case of intentional discrimination.0 But this

Court has stressed that the McDonnell Douglas formula

tion is not the only means by which a plaintiff may es

tablish a disparate treatment claim. Teamsters, supra,

431 U.S. at 358 (decision in McDonnell Douglas “ did not

purport to create an inflexible formulation” ). In a case

where the plaintiff’s claim is that a pattern or series of

employment decisions are discriminatory, plaintiff’s proof

will often be statistical in nature. 9

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank, supra, 467 U.S. at 876 n.9, there

is no reason why an individual plaintiff could not make out a case

according to the “pattern or practice” order of proof, so long as

that plaintiff shows that he was personally affected by the discrimi

natory policy. E.g., Davis V. Califano, 613 F.2d 957, 962-66 (D.C.

Cir. 1979) (individual plaintiff established a prima facie case of

discrimination through elements of a pattern or practice claim set

forth in Teamsters) ; Diaz v. American Tel. & Tel., 752 F.2d 1356,

1363 (9th Cir. 1985) (statistical evidence of a discriminatory pat

tern in employer’s hiring or promotion practices can “create an

inference of discriminatory intent” with respect to employment

decision at issue in action brought by individual plaintiff).

9 Under the McDonnell Douglas formulation, a plaintiff may

establish a prima facie case of intentional discrimination “by show

ing (i) that he belongs to a racial minority; (ii) that he applied

and was qualified for a job for which the employer was seeking

applicants; (iii) that, despite his qualifications, he was rejected;

and (iv) that, after his rejection, the position remained open and

the employer continued to seek applicants from persons of com

plainant’s qualifications.” 411 U.S. at 802.

13

Statistical proof that an employment practice is dis

criminatory will generally involve a showing of a statis

tical disparity between the race or sex of the group

selected by the practice, and the race or sex of the group

available for the job, such as the general work force, the

qualified labor market, or actual applicants. Hazelwood

School Dist. v. United States, supra, 433 U.S. at 308

(proper comparison in teacher hiring discrimination case

was between racial composition of teaching staff and

racial composition of “ qualified public school teacher

population in the relevant labor market” ) ; Johnson v.

Transportation Agency, 107 S. Ct. 1442, 1452 n.10

(1987) (to make out a prima facie case of hiring dis

crimination among skilled workers in Kaiser work force,

plaintiff “would be required to compare the percentage of

black skilled workers in the Kaiser work force with the

percentage of black skilled craft workers in the area labor

market” ). Statistical evidence of such a disparity is

“ probative” in a case alleging systemic discrimination

“ because such imbalance is often a telltale sign of pur

poseful discrimination.” Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at

340 n.20. As this Court has noted, “ absent explanation,

it is ordinarily to be expected that nondiscriminatory

hiring practices will in time result in a work force more

or less representative of the racial and ethnic composi

tion of the population in the community from which em

ployees are hired.” Id.

Although this Court has never defined exactly what

degree of disparity must be shown to make out a prima

facie case of intentional discrimination, it noted, in Hazel

wood School Dist. v. United States, supra, that if the dif

ference between the expected and observed number of

blacks on the Hazelwood teaching staff were greater than

two or three standard deviations, “ then the hypothesis

that teachers were hired without regard to race would be

suspect.” 433 U.S. at 309 n.14, citing Castaneda v.

Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 496-97 & n.17 (1977). This makes

14

sense, since two standard deviations corresponds to sta

tistical significance at the .05 level, which means in turn

that “ there exists at most a one in 20 possibility that

the observed result could have occurred by chance.”

Segar v. Smith, supra, 738 F.2d at 1282-83 & n.28.

Hazelwood stands for the point, therefore, that when a

plaintiff has shown a disparity equal to two standard

deviations or of statistical significance at the .05 level—

and thus that there is only one chance in twenty that

the disparity could be explained by chance— the plain

tiff’s evidence is normally sufficient to make out a case

of intentional discrimination. See Segar v. Smith, supra,

738 F.2d at 1282-83 (several courts and the Department

of Justice have taken the position that a disparity be

tween the group available for a job and the group se

lected which is statistically significant at the .05 level

is sufficient to support an inference of intentional dis

crimination) ; B. Schlei & P. Grossman, Employment

Discrimination Law 1372 (1983) (same). See generally

D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of Discrimination

§§ 9.0-9.42 (1980 & Supp. 1986).

A plaintiff is not, of course, confined in a disparate

treatment action to statistical evidence, and often the

plaintiff s statistical case will be buttressed by other evi

dence supporting the claim of intentional discrimination.

Examples of such other evidence include anecdotal evi

dence of discrimination, Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at

339; Hazelwood, supra, 433 U.S. at 303; a history of

discrimination by the employer and ineffectual attempts

by the employer to eradicate such discrimination, Baze-

more v. Friday, 106 S. Ct. 3000, 3009 (1986); Hazel

wood, supra, 433 U.S. at 303, 309 n.15; or “ standardless

and largely subjective [employment] procedures.” Hazel

wood, supra, 433 U.S. at 303.10 There is no prescribed

10 Courts have repeatedly recognized that evidence of subjective

employment practices can buttress statistical evidence of disparate

treatment. E.g., O’Brien v. Sky Chefs, Inc., 670 F.2d 864, 867

15

formula concerning when such nonstatistical evidence is

needed to make out a case of disparate treatment; the

question in each case is simply whether the sum of evi

dence presented by the plaintiff is sufficient to support

the inference of intentional discrimination. Bazemore v.

Friday, supra, 106 S. Ct. at 3009. See Segar v. Smith,

supra, 738 F.2d at 1278 (“neither the presence nor the

absence of specific anecdotal accounts alters the stand

ard that a plaintiff’s initial case must meet;” issue is

whether plaintiff’s “cumulative” evidence is “ sufficient to

support an inference of discrimination” ).

Once the plaintiff has made out a prima facie case of

disparate treatment, whether by statistical evidence alone

or by a combination of statistical and nonstatistical evi

dence, a burden of rebuttal shifts to the employer; this

follows from the fact that if the employer is silent and

the trier of fact believes the plaintiff’s evidence, the

plaintiff must prevail.

The sort of rebuttal evidence an employer will offer to

a strong statistical and nonstatistical showing of inten

tional discrimination will typically include an attempt to

discredit the nonstatistical evidence and to refute plain

tiff’s claim that a statistical disparity exists, by attack

ing the accuracy of plaintiff’s statistics or offering alter

native statistical analyses. Alternatively, the employer

may offer evidence explaining the disparity shown by

plaintiff’s statistics, such as by “com [ing] forward with

some additional job qualification * * * that the plaintiff

class lacks, thus explaining the disparity.” Segar v.

(9th Cir. 1982), overruled on other grounds, Atonio v. Wards Cove

Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477 (9th Cir. 1987) (en banc) ( “ subjective

decisionmaking strengthens an inference of discrimination from

general statistical data” ) ; Harris V. Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609,

611 (8th Cir. 1981) ( “ Nonobjective evaluation systems may be

probative of intentional discrimination, especially when discrimi

natory patterns result, because such systems operate to conceal

actual bias in decisionmaking.” )

16

Smith, supra, 738 F.2d at 1268; Teamsters, supra, 431

U.S. at 360 (on rebuttal'to a pattern or practice show

ing, employer will try to demonstrate that the plaintiff’s

proof “ is either inaccurate or insignificant” ).11

Under the McDonnell Douglas formulation, an em

ployer may rebut a plaintiff’s prima facie case simply by

offering, through admissible evidence, a legitimate, non-

discriminatory reason for the plaintiff’s non-selection.

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S. at

802; Texas Dep’t of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248, 255 (1981).12 This minimal rebuttal burden

is tailored to the minimal evidence a plaintiff must offer

to make out a prima facie case of intentional discrimina

tion under McDonnell Douglas (see p. 12, note 9, supra) ;

given plaintiff’s minimal showing, evidence by the de

fendant of a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for

plaintiff’s non-selection is sufficient to allow a factfinder

to decline to draw the inference of intentional discrimi

nation. See Burdine, supra, 450 U.S. at 254-55 ( “ The

11 If, in rebuttal to a statistical case of disparate1 treatment, the

employer offers evidence that a specific employment practice, such

as an experience requirement, explains the disparity, the case will

be transformed into a disparate impact case, and the employer

will bear the burden of proving that the employment practice

it has identified is justified by business necessity. Segar v. Smith,

supra, 738 F.2d at 1270, 1288; Latinos Unidos de Chelsea en

Accion (Lucha) V. Secretary of Housing and TJrhan Development,

799 F.2d 774, 787 n.22 (1st Cir. 1986); Lewis v. Bloomsburg Mills,

773 F.2d 561, 571 n.16 (4th Cir. 1985); Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d

1516, 1526-28 (11th Cir. 1985); Vuyanich V. Republic Nat’l Bank

of Dallas, 521 F. Supp. 656, 662 (N.D. Tex. 1981), vacated on

other grounds, 723 F.2d 1195 (5th Cir. 1984). See generally,

Bartholet, Application of Title VII to Jobs in High Places, 95

Harv. L. Rev. 947, 1005-06 (1982).

12 Because the “legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason” must be

presented through “admissible” evidence, neither “ [a]n articula

tion not. admitted into evidence,” “an answer to the complaint,”

nor “argument of counsel” will be sufficient. Texas Dep’t of Com

munity Affairs v. Burdine, supra, 450 U.S. at 255 n.9.

17

explanation provided must be legally sufficient to justify

a judgment for the defendant.” )

By contrast, when the plaintiff has offered strong

statistical evidence or a combination of strong statistical

and nonstatistical evidence supporting the inference of

intentional discrimination, an employer must do more

than articulate a “ legitimate, nondiscriminatory” expla

nation for plaintiff’s evidence to adequately rebut the

plaintiff’s case. This follows from the fact that if plain

tiff has presented strong statistical and nonstatistical

evidence of intentional discrimination, the mere articula

tion of a nondiscriminatory explanation for that evidence

— without more— will be insufficient to allow a factfinder

to find for the employer. Thus, in Paxton v. Union Nati

Bank, 688 F.2d 552, 566 (8th Cir. 1982), the court of

appeals reversed the district court’s finding of no dis

crimination in promotions, where the plaintiffs presented

strong statistical and nonstatistical evidence of inten

tional discrimination, and the employer’s “ vague asser

tion that black employees as a whole within the bank

were not as qualified as the white employees,” and “ ad

hoc, contradictory and conflicting explanations” for in

dividual promotion decisions “ [did] not even begin to ex

plain the broad pattern of promotional discrimination”

shown by plaintiffs. See also Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S.

at 343 n.24 ( “ ‘affirmations of good faith in making in

dividual selections are insufficient to dispel a prima facie

case of systematic exclusion’ ” ) ; Segar v. Smith, supra,

738 F.2d at 1269-70 (“ in the class action pattern or prac

tice case[,] the strength of evidence sufficient to meet

[the employer’s] rebuttal burden will typically need to

be much higher than the strength of the evidence suffi

cient to rebut an individual plaintiff’s low-threshold Mc

Donnell Douglas showing” ) ; Vuyanich v. Republic Nat’l

Bank of Dallas, 521 F. Supp. 656, 663 (N.D. Tex. 1981),

vacated on other grounds, 723 F.2d 1195 (5th Cir. 1984)

(same).

18

Once the defendant has offered rebuttal evidence, the

plaintiff may attempt to discredit the rebuttal or may

instead rely solely on his or her initial proofs. Burdine,

supra, 450 U.S. at 256; Segar v. Smith, supra, 738 F.2d

at 1270 n.15. At that point, the issue for the trier of

fact is whether, “ in light of all the evidence presented

by both the plaintiff and defendant * * * it is more likely

than not that impermissible discrimination exists.” Baze-

more v. Friday, supra, 106 S. Ct. at 3009. If plaintiff’s

statistical evidence, significant to two or three standard

deviations, has not been undermined and defendant has

not convincingly (and lawfully) justified the disparity,

plaintiff should prevail.13

The evidence presented by a plaintiff in a disparate

impact challenge to a subjective employment practice will

be similar in many respects to that presented in a dis

parate treatment challenge. The plaintiff will offer evi

dence of a statistical disparity between the race or sex

of the group selected by the practice, and the race or sex

of the group available for the job, composed of the gen

13 I f a pattern or practice of discrimination is established, and

a proceeding moves to the remedy stage, the burden of proof rules

are different. As this Court held in Teamsters, supra, “proof of the

pattern or practice [of discrimination] supports an inference that

any particular employment decision, during the period in which

the discriminatory policy was in force, was made in pursuit of that

policy.” Thus, at the remedial stage, plaintiffs “need only show

that an alleged individual discriminatee unsuccessfully applied for

a job and therefore was a potential victim of the proved discrimina

tion. At that point, “ the burden then rests on the employer to

demonstrate that the individual applicant was denied an employ

ment opportunity for lawful reasons.” 431 U.S. at 362 (citing

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747, 773 n.32 (1976)).

Moreover, many courts have held that the employer’s burden of

proof at the remedy stage is by clear and convincing evidence.

E.g., Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1094, 1107 (D.C. Cir. 1983),

vacated on other grounds, 465 U.S. 1056 (1984) & cases cited;

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437, 443-44

(5th Cir. 1974).

19

eral workforce, the qualified labor market, or actual ap

plicants for the job. E.g., Dothard v. Raivlinson, 433

U.S. 321, 329-30 (1977) (height and weight require

ments for prison guards have a disparate impact on fe

males where standards would exclude from employment

41.13% of the female population and only 1% of the male

population).14 As in disparate treatment actions, this

Court has never defined precisely what magnitude of dis

parity is required to make out a case of disparate impact.

The cases have referred to a showing that a requirement

disqualifies a suspect group “ at a substantially higher

rate” than white applicants, Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

426; or that a given employment practice “ select [s] ap

plicants for hire or promotion in a racial pattern signifi

cantly different from that of the pool of applicants.”

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 425.

It is possible that a disparity less than two standard

deviations might suffice. See, e.g., D. Baldus & J. Cole,

supra, § 9.221 (Supp. 1986).

Because employers frequently have selection procedures

which combine many components, both subjective and ob

jective, a plaintiff making a disparate impact challenge

must be allowed to make a case— as plaintiffs may in dis

parate treatment actions— by showing that the selection

procedure as a whole has produced a statistical disparity

between the group selected under the procedure and the

group available for the job. The plaintiff should not also

have to identify which specific selection component caused

the adverse impact. E.g., Griffin v. Carlin, 755 F.2d 1516,

1523-25 (11th Cir. 1985). See also Connecticut v. Teal,

supra, 457 U.S. at 458 (Powell, J., dissenting) ( “ our dis

14 Because disparate impact suits necessarily challenge a series

of employment decisions, they often proceed as class actions. But

individual plaintiffs may also bring disparate impact claims. E.g.,

Coe V. Yellow Freight System, 646 F.2d 444, 451 (10th Cir. 1981)

(individual may bring a disparate impact claim so long as he

satisfies requirement of standing by showing that he was affected

by the practices alleged to have disparate impact).

20

parate-impact cases consistently have considered whether

the result of an employer’s total selection process had an

adverse impact upon the protected group” ) (emphasis in

original). The data necessary for such an identification

is often prohibitively expensive for plaintiffs to obtain

and is more readily available to the employer. Moreover,

limiting disparate impact analysis to cases in which the

plaintiff is able to show that a particular component of a

multi-component selection procedure caused adverse im

pact would completely exempt the situation when two or

more components interact together to produce a disparate

impact. See Griffin v. Carlin, supra, 755 F.2d at 1516,

citing Gilbert V. City of Little Rock, 722 F.2d 1390, 1397-

98 (8th Cir. 1983).

On the employer’s side, the rebuttal evidence offered

to a disparate impact showing will be similar in many

respects to the rebuttal evidence offered in a disparate

treatment action. Indeed, since plaintiff will often have

presented the two types of analysis in the same case, em

ployers must often deal with both at once. The rebuttal

will likely involve an attack on plaintiff’s statistics, either

directly or by alternative statistical analyses. At this

point, however, disparate impact and disparate treatment

theories diverge. In a disparate impact case, once the

plaintiff has proven that a given employment practice has

adverse impact, the burden of proof shifts to the em

ployer to show that the practice is job-related or justi

fied by business necessity. Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

432 (in disparate impact cases, “ Congress has placed on

the employer the burden of showing that any given re

quirement [has] a manifest relationship to the employ

ment in question.” ). Accord, Dothard V. Rawlinson,

supra, 433 U.S. at 329; Connecticut v. Teal, supra, 457

U.S. at 446-47. Thus, while an employer can defend

against a disparate treatment challenge by rebutting

plaintiff’s showing of intentional discrimination, an em

ployer must do more to defeat a showing of adverse im

21

pact; the employer must prove that the employment prac

tice is job-related or justified by business necessity.15

This critical difference between disparate impact and

disparate treatment analysis demonstrates that confin

ing challenges to subjective employment practices to dis

parate treatment theory would defeat a central purpose

of Title VII. In Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at 431, this

Court held that Title VII was intended to proscribe not

only “ overt discrimination,” “ but also practices that are

fair in form, but discriminatory in operation.” Further,

“ Congress directed the thrust of the Act to the conse~

quences of employment practices, not simply the motiva

tion.” Id. at 432 (emphasis in original). Thus, Griggs

held, Congress intended in Title VII that employment

practices with bad consequences (an adverse impact on a

suspect group) must be justified, by business necessity

or as job-related, to be lawful. Id. at 431. See also

Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 248 (under

Griggs, an employment practice “ designed to serve neu

tral ends is nevertheless invalid, absent compelling jus

15 Even if the employer proves a business necessity defense, the

plaintiff may still prevail if he shows “that other tests or selection

devices, without a similarly undesirable * * * effect, would also

serve the employer’s legitimate interest in ‘efficient and trust

worthy workmanship.’ ” Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, supra, 422

U.S. at 425. Accord, Dothard v. Rawlinson, supra, 433 U.S. at 329.

As in disparate treatment actions (see p. 18, note 13, supra),

once an unjustified disparate impact is established and the case

moves to the remedy stage, individual plaintiffs need only show

that they were affected by the employment policy with adverse

impact, and the employer then bears the burden of proving that

the plaintiff would have been denied the employment opportunity

absent discrimination. E.g., Association Against Discrimination in

Employment, Inc. v. City of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256, 289 (2d Cir.

1981); Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625, 637 (4th Cir.

1978). Again, as in disparate treatment actions, courts have held

that the employer’s burden of proof at the remedy stage is by

clear and convincing evidence. E.g., Stewart v. General Motors

Corp., 542 F.2d 445, 453 (7th Cir. 1976).

22

tification, if in practice it benefits or burdens one race

more than another” ). Confining challenges to subjective

employment practices to disparate treatment analysis

would, therefore, defeat this central purpose of Title VII.

Under disparate treatment analysis, subjective employ

ment practices with an adverse impact on suspect groups

would not need to be justified to be lawful, so long as

they were not found to be intentionally discriminatory.16

C. Allowing Disparate Impact Challenges to Subjec

tive Employment Practices Will Not Leave an Em

ployer Without a Defense to a Disparate Impact

Showing.

In its amicus brief on petition for certiorari, the United

States suggests that an exemption from disparate im

pact analysis for subjective employment practices is war

ranted because such practices “may not be susceptible to

validation or other such objective substantiation.” U.S.

Cert. Brief at 15. Thus, the argument goes, to apply dis

parate impact analysis to employment practices involving

subjectivity would leave an employer “with no possible

defense” to a disparate impact showing. Id. at 19-20.

16 It should also1 be noted that confining challenges to subjective

employment practices to disparate treatment analysis would en

courage employers to make most of their practices subjective.

Courts have recognized that subjective practices can more easily

mask discriminatory motivation than objective ones. Miles V.

M.N.C. Corp., 750 F.2d 867, 871 (11th Cir. 1985) (subjective

evaluations involving white supervisors provide a “ ready mecha

nism” for racial discrimination). Accord, Rowe v. Cleveland

Pneumatic Co., 690 F.2d 88, 93 (6th Cir. 1982); Rowe v. General

Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 359 (5th Cir. 1972). See also p. 14,

note 10, supra. Yet it could not have been the intent of Congress

to encourage employers to use subjective devices in place of objec

tive criteria. Atonio V. Wards Cove Packing Co., supra, 810 F.2d

at 1485 ( “ It would subvert the purpose of Title VII to create an

incentive to abandon efforts to validate objective criteria in favor

of purely discretionary hiring methods.” ) Griffin v. Carlin, supra,

755 F.2d at 1525 (sam e).

23

This Court has never held, however, that formal valida

tion is the only defense to a showing that an employment

practice has adverse impact. Instead, the cases have

spoken of the need for the employer to show that the

employment practice has a “manifest” or “ demonstrable”

relationship to the job in question, Griggs, supra, 401 U.S.

at 431, 432; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422

U.S. at 425; or that it is “ necessary to safe and efficient

job performance * * *.” Dothard v. Rawlinson, supra, 433

U.S. at 332 n.14. See also Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

431 (the “ touchstone” of the defense to a disparate im

pact claim is a showing of “ business necessity” ) ; Nash

ville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136, 143 (1977) (issue

is whether “ company’s business necessitates the adoption”

of employment practice at issue). Moreover, this Court

has held that the defense may be made out on evidence

other than a formal validation study. E.g., New York

Transit Authority v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568, 587 & n.31

(1979) (even if employer’s rule excluding all users of

narcotics and certain other drugs from employment had

an adverse impact, rule would be sustained because em

ployer has shown that rule serves employer’s “ legitimate

employment goals of safety and efficiency” ). See gen

erally B. Schlei & P. Grossman, supra, at 164 (courts

have generally not required that education and other

nonscored employment criteria be validated, allowing job

relatedness to be shown by other evidence), citing, e.g.,

Spurlock v. United Airlines, Inc., 475 F.2d 216, 219

(10th Cir. 1972) (upholding college degree requirement

for airline pilots based on testimony by airline officials);

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725, 735 (1st Cir. 1972)

(upholding high school diploma requirement for police

officers based on Kerner Commission recommendation

that all police officers have a high level of education).

Thus, an employer may be able to sustain a subjective

employment practice with adverse impact that cannot

feasibly be validated if, for example, the employer offers

24

evidence to show that continued use of the practice is

essential to its business, and that it has instituted safe

guards to ensure that discretion is focused on job-related

variables and that subjectivity is not being used to mask

intentional or unintentional discrimination. E.g., Stew

art v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445, 450-51 (7th

Cir. 1976) (business necessity defense to subjective pro

motion process not made out where “ supervisory recom

mendations play an important role” in promotions, but

foremen, who are all white, “have no objective way of

rating the employees,” and have no “written guidelines

delineating the criteria” for which they are looking) ;

Roive v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 358-59

(5th Cir. 1972) (subjective promotion/transfer proce

dures fail business necessity test where foremen’s recom

mendations are the “ indispensable single most important

factor,” but foremen receive “ no written instructions” on

criteria to be applied and hourly employees are not noti

fied of jobs available or qualities necessary for promo

tion) ,17

17 The Uniform Guidelines provide that in circumstances when

an employment procedure has adverse impact and an employer “can

not or need not utilize the validation techniques contemplated by

these guidelines,” the employer should “ justify continued use of

the procedure in accord with Federal law.” 29 C.F.R. § 1607.6

(B) (1) & (2) (1986). Since the only method under “ Federal law” to

justify an employment procedure with adverse impact is to show

that the procedure is job-related or justified by business necessity,

the Guidelines clearly anticipate that those defenses may be made

out in some circumstances without formal validation. This inter

pretation of the Guidelines is confirmed in the EEOC’s questions

and answers designed to clarify the Guidelines. 44 Fed. Reg.

11996 (March 2, 1979). There, in response to a question concern

ing whether a selection procedure could be justified without valida

tion, the EEOC stated that, under Griggs, a “ selection procedure

could be used if there was a business necessity for its continued

use,” and that “ therefore, the Federal agencies will consider evi

dence that a selection procedure is necessary for the safe and effi

cient operation of a business * * *.” Id. at 12002.

25

Furthermore, there is no apparent reason why certain

subjective criteria cannot be validated in the same man

ner as objective criteria. As Professor Bartholet points

out:

“ The validity of a written test is traditionally es

tablished by correlating the scores of candidates who

passed the test and are on the job with indicia of

their job performance. A subjective assessment proc

ess, like a written test, can be scored even if only for

the purpose of conducting a validity study. Alterna

tively, an employer can establish the validity of sub

jective processes by proving that the behavior assessed

by the process represents a fair sample of the be

havior required in the job at issue, or that the sub

jective process measures the knowledge, skills or abil

ities that are the necessary prerequisites to the job.

“ The industrial psychology literature * * * con

tains numerous descriptions of validity studies of the

most commonly used subjective processes, such as

interviews, the evaluation of biographical data, and

assessment center techniques.” (Citations omitted.)

Bartholet, Application of Title VII to Jobs in High

Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947, 987-88 (1982). It may be

that validation techniques developed for certain objective

employment practices, such as scored tests, will have to

be modified, or new validation techniques developed for

subjective practices such as interviews. Id. at 989, 985

n.133. But these issues are not before the Court at this

time. The fact that validation of some subjective employ

ment practices may, in certain cases, be difficult or call

for new validation techniques, does not justify the crea

tion by this Court of an across-the-board exemption from

disparate impact analysis for all employment practices

involving subjective decisionmaking.

26

CONCLUSION

If an employer need make no business-related defense

of his subjective or discretionary employment practices,

such practices may have a substantially adverse impact

on suspect groups for no good reason whatsoever. Title

VII should not be construed to permit such a result, and

thus the disparate impact analysis of Griggs should not

be restricted in ways that undercut a central purpose of

Title VII. For the reasons stated above and in the Brief

for the Petitioner, amicus Lawyers’ Committee urges the

Court to reverse the decision below.

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

N orman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Richard T. Seymour

John Townsend Rich *

Elizabeth Runyan Geise

Nancy B. Stone

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 “ Eye” Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law

September 14,1987 * Counsel of Record