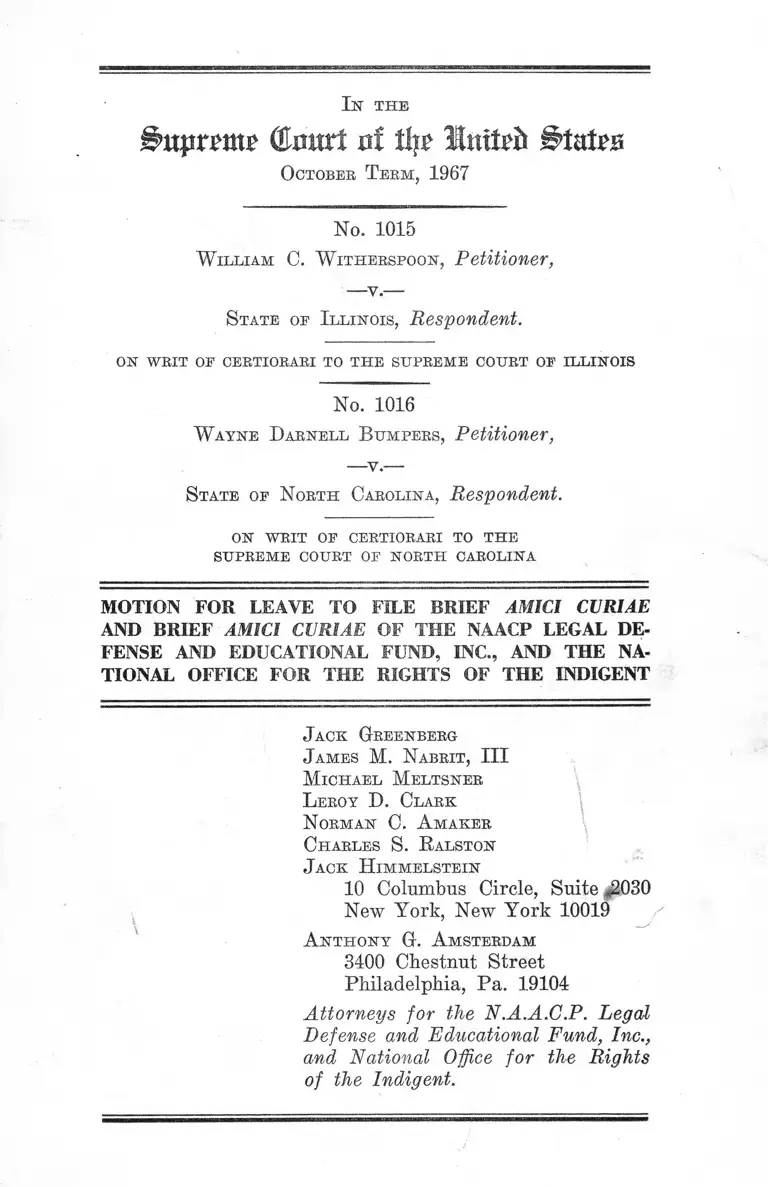

Witherspoon v. Illinois Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Witherspoon v. Illinois Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae, 1967. fa136466-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95393d05-fdcc-429b-b7ce-5f9592c820c6/witherspoon-v-illinois-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

i>tqir£m£ (Emtrt ni tip Huttein Btnttz

October Term, 1967

No. 1015

W illiam C. W itherspoon, Petitioner,

S tate op Illinois, Respondent.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP ILLINOIS

No. 1016

W ayne Darnell Bumpers, Petitioner,

State op North Carolina, Respondent.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO TH E

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DE

FENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE NA

TIONAL OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

Leroy D. Clark i

Norman C. A maker

Charles S. Ralston

Jack H immelstein

10 Columbus Circle, Suite #2030

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

and National Office for the Rights

of the Indigent.

jX-.v

P q ' ? - 7

' xS - . . . ? , " - ; b

f < r .

•Z> £,

) 7 ‘

1 7 , ' O ^ f . ' V • O 1, v -' \

fe '/f

c/ ■■

V . V - o ) \) ’jr

V •/. H . > * N o

s . , O f o s 7

" ' - x . ' ^9

A -J A'?, \ Q)L~

JaV scf j <*%

/®,

Vfir ,

/ r'*'sv c. rfj ' C

J v ,, *5.XhC Vv_ "x < <f '*■* XX y H -x

V

r C V«L> •

X f t if V

W J

V

? ■ /* *

\;

j

I N D E X

Motion for Leave to File Brief Arniei Curiae and State

ment of Interest of the A m ici....................................... 1-M

Brief Amici Curiae..... ......................................................... 1

Statement ....................................................... .............. 1

Summary of Argum ent............................................... 9

A rgument :

I. This Court Should Not Decide the Serupled-

Juror Issue in Isolation From Other Belated,

Substantial Federal Constitutional Challenges to

Capital Trial Proceedings ....................................... 12

A. The Scrupled-Juror Issue in Context ........... 12

B. A Summary of Capital Trial Procedure ....... 16

C. The Federal Constitutional Violations En

tailed by the Procedure ................................... 20

D. The Interrelatedness of the Constitutional

Points ....................................... 22

E. Conclusion .......................... 28

II. This Court Should Not Decide the Scrupled-Juror

Question on an Inadequate Record ......... - ......... 30

A. The Nature of the Legal Issues Presented .... 30

1. The Practice of Death-Qualifying Jurors - 31

2. The Theories of Constitutional Objection

to the Practice ........... 33

3. The Substantiality of the Constitutional

Objections ......................... 37

B. The Importance of Factual Matters to De

cision of the Legal Questions ........................... 51

PAGE

11

PAGE

1. The Pertinent Factual Inquiries .......... . 54

2. The State of the Record on These Factual

Questions ................................................... 56

3. The Present State of the Art on These

Factual Questions ........................................... 56

4. Materials That Could Be Presented at an

Evidentiary Hearing ........ 61

C. The Consequent Desirability of an Eviden

tiary Hearing ........... 68

III. The Witherspoon Case Should Be Reversed and

the Bumpers Case Reversed or Remanded......... . 74

A. The Witherspoon Case ................. .......... ......... . 74

B. The Bumpers Case ........ ...................................... 75

IV. The Problem of Retroactivity .......... 77

A. The Court Should Not Decide the Question

of Retroactivity at This Time ......... ...... .......... 79

B. The Ruling on the Scrupled Juror Question

Should Be Applied Retroactively to Those

Cases in Which the Death Penalty Has Actu

ally Been Imposed .............. ............. ......... .......... 85

Conclusion .... ........ .......................... ........ ......................... 94

A ppendix I—

Excerpts from the Voir Dire Examinations Of

Prospective Jurors McCarley and Lewis In Peo

ple v. Arguello (Tr. 308-311), Now Pending on

Federal Habeas Corpus Sub. Nom. Arguello v.

Nelson, U.S.D.C., N.D. Cal. No. 47622 ________ la

Ill

PAGE

A ppendix II—

Excerpt From the Yoir Dire Examination Of Pro

spective Juror Timberlake, In People v. Saterfield

(Tr. 83-85), Now Pending On Habeas Corpus,

Matter of Saterfield, Cal. S.C. Crim, No. 11573 ....

A ppendix III—

Excerpt From the Voir Dire Examination Of Pro

spective Juror Upchurch, in People v. Schader

(Tr. 247), Appeal Pending, Cal. S. C. Crim. No.

9855 .................................................................................

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Adderly v. Wainwright, M.D. Fla., No. 67-298-

Civ.-J................ .......... .......................................... 4-M, 5-M,

Arkwright v. Kelly, Super. Ct. Tattnall Cty, Ga.

No. 5283 ........................................................... ...... .........

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143 (1944) ...............

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219 (1911) ......... ........ .

Bell v. Patterson, U.S.D.C., D. Colo., No. 67-C-458 ....

Billingsley v. Clayton, 359 F.2d 13 (5th Cir. 1966) ....

Borden’s Farm Products Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S.

194 (1934) .... ............... ................................ ................. 71,

Brent v. White, 5th Cir., No. 25496 ..........................

Bresolin v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 214 (1967) .......................

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953) ...........................

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....

Brown v. Lane, U.S.D.C., N.D. Ind., No. 4129 ...........

4a

6a

12

14

77

47

14

37

72

14

80

38

72

14

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89 (1965) ............. .

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) ................. .

Chastleton Corp. v. Sinclair, 264 U.S. 543 (1924)

47

43

71

IV

Chevalier v. Beto, U.S.D.C., S.D. Tex., No. 68-H-57 .... 14

Childs v. State, Super. Ct. Buncombe Cty., N.C............ . 76

Childs v. Turner, U.S.D.C., W.D.N.C., No. 2663 ............ 14

Clarke v. Grimes, 374 F.2d 550 (5th Cir. 1967) .......... 15

Crain v. Beto, U.S.D.C., S.D. Tex., No. 66-H-626 ...... . 15

Craig v. Wainwright, U.S.D.C., M.D. Fla., No. 66-

595-Civ.-J. ................................................. ................ ..... 12

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) ............... 47

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ............... 22

Duncan v. Louisiana, O.T. 1967, No. 410........... ..... ......... 36

Ellison v. Texas, U.S., Misc. No. 1311 ........ ..... ............ 15

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ............. 89

Evans v. Dutton, 5th Cir., No. 25348 ...................... 15

Fay v. x\Tew York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947) ________ 2,38,87

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) .......... .............. ......... 4-M

Gaster v. Goodwin, 259 N.C. 676, 131 S.E.2d 363

(1963) .......... ..... ........ ............... .............................. ........ 76

Gaylord v. Berry, 169 N.C. 733, 86 S.E. 623 (1915) ....... 76

Gebhart v. Belton, 87 A.2d 862 (Del. Ch. 1952) ........... 72

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966) .............. . 20

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) ........ ...... 22,79

Giles v. Maryland, 386 U.S. 66 (1967) __ _______ ___ _ 76

Greensboro Bank & Trust Co. v. Royster, 194 N.C.

799, 139 S.E. 774 (1927) ......................... ......... .......... 76

Gulf Refining Co. v. McKernan, 178 N.C. 82, 100 S.E.

121 (1919) .............. ..... .................. ...................... .......... 76

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U.S. 52 (1961) ................... 22,88

Hardy v. United States, 186 U.S. 224 (1902) ...... ....... 2

Harper v. Virginia, 383 U.S. 663 (1966) .................. 45

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ....................... 38

PAGE

V

Hill v. Nelson, N.D. Cal., No. 47318 ............................ 5-M, 13

In the Application of Anderson, Cal. S.C., Crim. No.

11572 ............................................................................ 5-M; 13

In the Application of Saterfield, Cal. S.C., Crim No.

11573 ............................ ................... ...... ..................... 5-M; 13

In re Gault, 387 TT.S. 1 (1967) .......................-............ -.... 73

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961) ............................... 36,46

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964) ........ .................. 79

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966) .......78,79,80,

81, 82, 90

Juarez v. State, 102 Tex. Cr. 297, 277 S.W. 1091 (1925) 38

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967) .... 53

Rabat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966) .......37, 38, 47

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) ...... ........ 78, 79, 82

Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 263 (1892) ................. 2

Massachusetts v. Painten, 19 L.Ed.2d 770 (1968) ______ 70

Matters of Sims and Abrams, 5th Cir., Nos. 24271-2 .... 3-M

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) ______3-M, 6-M; 14

McNeal v. Culver, 365 U.S. 109 (1961) .... ............ ......... 75

Memorial Hospital v. Rockingham County, 211 N.C.

205, 189 S.E. 494 (1937) ............. ........ ........... ............ 76

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 214 (1967) ................. ....... ..... 80

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ......... ..43, 73, 81, 89

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908) ..... ........ ................ 71

Moorer v. South Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (4th Cir.

1966) .................................................................................. 3-M

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1964) ................... 52

Nashville Chattanooga & St. Louis Ry. v. Walter's,

294 U.S. 405 (1935) ......... ........ ........................................ 72

PAGE

VI

Nelson v. Peckham, 9th Cir. No. 21969 ............................. 13

Nostrand v. Little, 362 U.S. 474 (1960) ......................... 76

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 663 (1948) ........ .............. 47

Palmer v. Peyton, 359 F.2d 199 (4th Cir. 1966) ........... 82

Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363 (1966) ................ 36

Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 600 (1934) ...... ..11,77

Pennsylvania ex rel. Herman v. Clandy, 350 U.S. 116

(1956) ........................... ....................... ........... ............... 75

People v. Carnso, 68 Adv. Cal. 181 (1968)..... ....... ......... 83

People v. Hobbs, 35 I11.2d 263, 220 N.E.2d 469 (1966) .... 2, 4

People v. Witherspoon, 36 IU.2d 471, 244 N.E.2d 259

(1967) ................................................................. ............. .4,62

Poole v. State, 194 So.2d 903 (Fla. 1967) ....................... 8

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ........................... 88

Pyle v. Kansas, 317 U.S. 213 (1942) ............................... 75

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1966) 38

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549 (1947) .. 70

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963) ....................... 36

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ................... 27

Rollins v. State, 148 So.2d 274 (Fla. 1963) ..... ............. 8

Segura v. Patterson, U.S.D.C., D. Colo. No. 67-C-497 .... 14

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) .......................... 52

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966)........... ......... . 36

Shinall v. Breazeale, 5th Cir., Misc. No. 978 ................. 14

Schowgurow v. State, 240 Md. 121, 213 A.2d 475 (1965) 38

Siros v. State, Dist. Ct. Harris Cty, Tex., No. 104617 .... 15

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ...................45, 46

Smith v. Nelson, 9th Cir., No. 22328 ..... .................. ...... 13

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ...............37, 39, 43, 47

Spencer v. Beto, 5th Cir., No. 25548 .............................. 14

PAGE

State v. Bumpers, 270 N.C. 521, 155 S.E.2d 173

( 1967) ........................................................ ......................... -....... . . - 6, 62,76

State v. Childs, 269 N.C. 307,152 S.E.2d 453 (1967)....6, 56, 76

State y. Funicello, Essex Cty. Ct., N.J., No. 2049-64 .... 14

State v. Carrington, 11 S.D. 178, 76 N.W. 326 (1898) .... 6

State v. Henry, 196 La. 217, 198 So. 910 (1940) ....... 8

State v. Lee, 91 Iowa 499, 60 N.W. 119 (1894) ______ 6

State v. Riggins, Wash. S.C., No. 39481 ___ 15

State v. Rocker, 138 Iowa 653, 116 N.W. 797 (1908) .... 6

State v. Scott, 243 La. 1, 141 So.2d 389 (1962)..... 7

State v. Smith, Wash. S.C., No. 39475 .................. 15

State v. Weston, 232 La. 766, 95 So.2d 305 (1957) ....... 8

State v. Wilson, 234 Iowa 60, 11 N.W.2d 737 (1943) .... 6

Stein v. New York, 346 U.S. 156 (1953) ....................... 88

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967) ....79, 81, 82, 83, 88,

89, 90

Tehan v. Shott, 382 U.S. 406 (1966) .............. ....... .78, 79, 82

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946) .... 38

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 (1945) ................ ..... 78

Tuberville v. United States, 303 F.2d 411 (D.C. Cir.

1962) .................... .......... ............................. ...... ............ 41

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 (1965) ..... ............. 36

United States ex rel. Smith v. Nelson, N.C. Cal.,

No. 48011 ........ ................................................................. 13

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967) ...... .73, 78,83

Villa v. Van Schaick, 299 U.S. 152 (1936) ....................... 76

W.E.B. DuBois Clubs of America v. Clark, 389 U.S.

309 (1967) ________________ ______ ______ ___________ 70

Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307 (1967) .... 78

Weaver v. Palmer Bros. Co., 270 U.S. 402 (1926) ....... 71

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) ........... 27

Wheat v. Washington, U.S., Misc. No. 1301................... 15

Vlll

White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966) .... 38

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) .......................... 38

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878) ......................... 27

Williams v. Dutton, 5th Cir., No. 25349 .................... ...... 15

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) ................. ..77, 88

Williams v. Kelly, Super. Ct. Tattnall Cty., Ga. No.

5284 .............................. ......... ...................... .................... 14

Wylde v. Wyoming, 362 U.S. 607 (1960) ...........................75

Statutes :

28 U.S.C. §2243 (1964) ........ .... ......... ................. ........... . 13

42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964) ...................................................... 21

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31 §1, 14 Stat. 27 ..... ............. 21

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18,

16 Stat. 140, 144 .............................................................. 21

111. Eev. Stat., 1959, Ch. 38, §743 ....................................... 2

Md. Code Ann., Art. 51, §8A (1967 Cum. Supp.) ..... . 7

Nev. Session Laws, 1967, p. 1472 ..... ..... ................ .......... 7

N.C. Gen. Stat. §9-14 (1953 Recomp. Vol.) ................... 6

S.D. Rev. Stat. §34.3618(10) ........ .................... ............. 6

Other Sources:

Adorno, et al., The Authoritarian Personality (1950) .. 61

Alfange, The Relevance of Legislative Facts in Consti

tutional Law, 114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 637 (1966) ............... 68

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tent.

Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959) .......................................... 18

PAGE

Annot., Beliefs Regarding Capital Punishment as Dis

qualifying Juror in Capital Case for Cause, 48 A.L.R.

2d 560 (1956) ............... ................................................... 7,

Bible, Judicial Determination of Questions of Fact A f

fecting the Constitutional Validity of Legislative Ac

tion, 38 Harv. L. Rev. 6 (1924) ..... .............. ..............

Christie & Cook, A Guide to Published Literature Re

lating to the Authoritarian Personality, 45 J. Psychol.

171 (1958) ..........................................................................

Crosson, An Investigation into Certain Personality

Variables Among Capital Trial Jurors, January, 1966

(unpublished) ..................................................................

Frankfurter, A Note on Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv.

L. Rev. 1002 (1924) ........... ...........................................

Goldberg, Attitude Toward the Death Penalty and

Performance as a Juror (unpublished) ...............

Greenberg, Social Scientists Take the Stand, 54 Mich.

L. Rev. 953 (1956) ..................... .................. ..................

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment,

284 Annals 8 (1952) ________ _____________ _______ 3

Impartial Juries, (Austin) Texas Observer, November

27, 1964, p. 5 ..... ....... ........... ...... ...............................

Kalven & Zeisel, The American Jury (1966) ________ 60,

Karst, Legislative Facts in Constitutional Litigation,

1960 Supreme Court Review 75 ------ ----------- -----------

Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital

Cases, 101 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1099 (1953) ______________ 7,

Louis Harris Survey, The Washington Post, Sunday,

July 3, 1966 ...... ...................... ........................... .............

34

68

61

59

71

58

72

-M

56

64

68

31

23

5

McClelland, Conscientious Scruples Against the Death

Penalty in Pennsylvania, 30 Pa. Bar Assn. Q. 252

(1959) ......................... ...... .............. ............. ...... ........... 7

Note, Jury Selection, 52 Ya. L. Rev. 1069 (1966) ........... 38

Note, Social and Economic Facts—Appraisal of Sug

gested Techniques for Presenting Them to Courts,

61 Harv. L. Rev. 692 (1948) ...... ........... ........................ 68

Oberer, Does Disqualification of Jurors for Scruples

Against Capital Punishment Constitute Denial of

Fair Trial on Issue of Guiltf 39 Texas L. Rev. 545

(1961) -----.....-..................... -....... ....... 7, 27,31, 34, 40, 49, 86

PAGE

Oberer, The Death Penalty and Fair Trial, The Nation,

Vol. 198, No. 15, p. 342 (April 6, 1964) ..... ............. 7

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice, Report, The Challenge of

Crime in a Free Society 143 (1967) .......................... 3-M

Report, of the Gallup Poll, Philadelphia Bulletin, Fri

day, July 1, 1966 ................................................. ............ 23

Shaw & Wright, Scales for the Measurement of Atti

tudes (McGraw-Hill Series in Psychology) (1967) .... 65

Sidney, Certain Determinants and Correlates of Au

thoritarianism, 49 Genetic Psych. Monographs 187

(1954) ........................... ....... .................................. ......... 61

U nited Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Capital Punishment (ST /SO A /SD /9)

(1962) ..... ...... ................................................................... 31

U nited Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Capital Punishment—Developments 1961-

1965 (ST/SOA/SD /IO ) 20 (1967) ....................... ...3-M, 31

XI

Weiliofen, The Urge to Punish (1956) ........................... 3-M

Wilson, Belief in Capital Punishment and Jury Per

formance (1964) (unpublished) ................. ............ 56

Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Executed

and the Commuted Among Admissions to Death

Row, 53 J. Grim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 301 (1962) .... 3-M

Zeisel, Some Insights into the Operation of Criminal

Juries, (1957) (unpublished) .... ...... .................... .60, 61, 62

PAGE

Ilf THE

Bum atm (tort of tfye United States

Octobeb T erm, 1967

No. 1015

W illiam C. W itherspoon,

— v.—

Petitioner,

State of Illinois,

Respondent.

on writ of certiorari to the

SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS

No. 1016

W ayne Darnell Bumpers,

— v .—

Petitioner,

State of N orth Carolina,

Respondent.

on writ of certiorari to the

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI

Movants N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and National Office for the Bights of the Indi

gent respectfully move the Court for permission to file the

attached brief amici curiae, for the following reasons. The

reasons assigned also disclose the interest of the amici.

2-M

(1) Movant N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under

the laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was formed

to assist Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by

the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its

purposes include rendering legal aid gratuitously to Ne

groes suffering injustice by reason of race who are unable,

on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on their

own behalf. The charter was approved by a New York

court, authorizing the organization to serve as a legal aid

society. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. (LDF), is independent of other organizations

and is supported by contributions from the public. For

many years its attorneys have represented parties in this

Court and the lower courts, and it has participated as

amicus curiae in this Court and other courts, in matters

resulting in decisions that have had a profoundly reform

ative effect upon the administration of criminal justice.

(2) A central purpose of the Fund is the legal eradica

tion of practices in our society that bear with discrimina

tory harshness upon Negroes and upon the poor, deprived,

and friendless, who too often are Negroes. In order more

effectively to achieve this purpose, the LDF in 1965 estab

lished as a separate corporation movant National Office

for the Eights of the Indigent (NOEI). This organization,

whose income is provided initially by a grant from the

Ford Foundation, has among its objectives the provision

of legal representation to the poor in individual cases and

the presentation to appellate courts of arguments for

changes and developments in legal doctrine which unjustly

affect the poor.

(3) LDF attorneys have handled many capital cases

over the years, particularly matters involving Negro de

3-M

fendants charged with capital offenses in the Southern

States. This experience has led us to the view, confirmed

by the studies of scholars1 and more recently by empirical

research undertaken under LDF auspices,2 that the death

penalty is administered in the United States in a fashion

that makes racial minorities, the deprived and downtrod

den, the peculiar objects of capital charges, capital con

victions, and sentences of death. Our experience has con

vinced us that this and other injustices are referrable in

part to certain common practices in capital trial procedure,

which depart alike from the standards of an enlightened

administration of criminal justice and from the minimum

requirements of fundamental fairness fixed by the Consti

tution of the United States for proceedings by which

human life may be taken. Finally, we have come to appre

ciate that in the uniquely stressful and often contradictory

litigation pressures of capital trials and direct appeals,

ordinarily handled by counsel appointed for indigent de

fendants, many circumstances and conflicts may impede

1 E.g., President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration

o f Justice, Report, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society 143 (1967) ;

United Nations, Department o f Economic and Social Affairs, Capital

Punishment—Developments 1961-1965 (ST /SO A /SD /IO ) 20 (1967);

W eih o fen , t h e U rge to P u n is h 164-165 (1956); Hartung, Trends in

the Use of Capital Punishment, 284 A n n a l s 8, 14-17 (1952); Wolfgang,

Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Executed and the Commuted Among

Admissions to Death Row, 53 J. Cr im . L., Cr im . & P ol. Soi. 301 (1962).

2 A study of the effect of racial factors upon capital sentencing for

rape in the Southern States (which virtually alone retain the death

penalty for that crime) was undertaken in 1965, with LDP financial

support, by Dr. Marvin E. Wolfgang and Professor Anthony G. Am

sterdam of the University of Pennsylvania. The nature of the study is

described in the memorandum appended to the report o f Moorer v. South

Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (4th Cir. 1966), and in Matter of Sims and

Abrams, 5th Cir. Nos. 24271-2, decided August 10, 1967. Its results, so

far analyzed, show persuasively that the death penalty is discriminatorily

applied against Negroes, at least in rape cases. One aspect of these re

sults, limited to the State of Arkansas, was presented in the record in

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967).

4-M

the presentation of attacks on these unfair and unconsti

tutional practices;3 and that in the post-appeal period, such

attacks are grievously handicapped by the ubiquitous

circumstances that the inmates of the death rows of this

Nation are as a class impecunious, mentally deficient, un

represented and therefore legally helpless in the face of

death.4 Common state practice makes no provision for the

furnishing of legal counsel to these men.

8 The constitutional challenge made in the present eases to the exclusion

of death-scrupled jurors presents one example of the “ grisly choice”

{Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 440 (1963)) that often confronts counsel in

raising these claims. To object to the death-qualification of a jury ordi

narily risks insulting the very jurors who will sit in a trial where the

defendant’s life is at stake. To proffer or present evidence that non-

serupled jurors are prosecution-prone (as we argue infra) compounds

the insult; and precautions to keep the proffer or the contention from

the knowledge of the veniremen are, as a practical matter, likely to be

ineffectual. Moreover, the attempt to secure a jury from which scrupled

veniremen are not excluded tends to suggest to the jurors who are

eventually empanneled that, at best, the defense is trying to hang the

jury, and, at worst, the particular case on trial is one in which only a

conscientiously scrupled juror would think the death penalty inappro

priate.

4 Recently, in connection with Adderly v. Wainwright, infra, LDF

lawyers were authorized by court order to interview all o f the condemned

men on death row in Florida. The findings o f these court-ordered inter

views, subsequently reported by counsel to the court, indicated that of

34 men interviewed whose direct appeals had been concluded, 17 were

without legal representation (exeept for purposes of the Adderly suit

itself, a class action having as one of its purposes to declare their con

stitutional right to appointment of counsel); 11 others were represented

by volunteer lawyers associated with the LDF or ACLU; and in the case

o f 2 more, the status o f legal representation was unascertained. All

34 men (and all other men interviewed on the row) were indigent; the

mean intelligence level for the death row population (even as measured

by a nonverbal test which substantially overrated mental ability in mat

ters requiring literacy, such as the institution or maintenance of legal

proceedings) was below normal; unrepresented men were more mentally

retarded than the few who were represented; most o f the condemned men

were, by occupation, unskilled, farm or industrial laborers; and the mean

number of years of schooling for the group was a little over eight years

(which does not necessarily indicate eight grades completed).

5-M

(4) For these reasons, amici LDF and NORI have un

dertaken a major campaign of litigation attacking on fed

eral constitutional grounds several of the most vicious

common practices in the administration of capital crimi

nal procedure, and assailing the death penalty itself as a

cruel and unusual punishment. The status of that litiga

tion is described more fully below. Suffice it to say here

that LDF and NORI attorneys, with the cooperation of

other lawyers, instituted class actions on behalf of the

more than fifty condemned men on death row in Florida

(.Adderly v. Wainwright, M.D. Fla., No. 67-298-Civ-J) and

the more than sixty condemned men on death row in Cali

fornia (Hill v. Nelson, N.D. Cal., No. 47318; Application

of Anderson, Cal. S.C., Crim. No. 11572; Application of

Saterfield, Cal. S.C., Crim. No. 11573), which have resulted

in interlocutory class stays of execution for all men under

sentences of death in those two States. In addition to the

120 prisoners represented in these class actions, our at

torneys have major responsibility for handling* forty pend

ing cases of men sentenced to death in ten other States,

and are cooperating with, or providing services to, attor

neys in half a hundred additional capital cases across the

country. Virtually all of these cases are in active litiga

tion; in most of them, stays of execution have been re

quired and were obtained; in the bulk of them (and in the

two class actions), the scrupled-juror question now pre

sented is raised; while, in virtually all of the remainder,

the question will be raised when procedurally ripe. In sum

mary, we represent or are assisting attorneys who repre

sent, more than half of the 400 men on death row in the

United States; and the lives of virtually all of these men

will be affected by the Court’s decision in the present

cases.

6-M

(5) In most of our cases in which the scrupled-juror

claim is advanced, we have presented it in conjunction with

several other federal constitutional contentions, not di

rectly raised in the Witherspoon and Bumpers cases, but

which are so intimately related to the scrupled-juror issue

that we believe this Court cannot properly view the latter

issue in isolation from them. We develop the pertinent as

pects of those relationships (without, however, arguing the

related points)5 in the attached brief. We have also com

missioned and are participating directly in the designing

of a large-scale empirical investigation, utilizing system

atically the methodology of the social sciences, that bears

directly on the scrupled-juror question, and which we de

scribe therein. We thus believe that we have information

and perspectives, not available to the parties before the

Court, which the Court should properly consider in its

deliberations upon the issues now before it.

(6) Counsel for the petitioners in Witherspoon and

Bumpers have consented to the filing of a brief amici

curiae by the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the

Indigent. The present motion is necessitated because coun

sel for the respondent State of Illinois has refused consent

in Witherspoon, and because we are advised by counsel

for North Carolina that the respondent in Bumpers “ takes

a neutral position and will neither affirmatively oppose

nor consent to . . . filing . . . a brief” amici curiae.

5 Two of these points— the contention that the unfettered, undirected

and unreviewable discretion habitually given juries to impose a punish

ment of life or death violates the rule of law basic to due process; and

the contention that the ordinary simultaneous-verdict procedure for capital

trials, under which a jury hears at one sitting the questions of guilt and

punishment, also offends the Constitution for several related reasons—

were presented in some detail in the petition for writ o f certiorari in

Maxwell v. Bishop, 335 U.S. 650 (1967) (O.T. 1966, Misc. No. 1025).

7-M

W herefore, movants pray that the attached brief amici

curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

L eroy D. Clark

Norman C. A maker

Charles S. Ralston

Jack H immelstein

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

and National Office for the Rights

of the Indigent.

I n th e

l̂ i!$iTOit£ (Emtri n i X\\ t United States

October Teem, 1967

No. 1015

W illiam C. W itherspoon,

-v.-

Petitioner,

State op Illinois,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OP CEETIOEAEI TO THE

SUPREME OOUET OP ILLINOIS

No. 1016

W ayne Darnell B umpers,

—v.—-

State op North Carolina,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OP NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Statement

The common question presented by these two cases is

whether the widespread state practice of “ death-qualifying”

a capital trial jury, by excusing for cause veniremen who

admit to having conscientious or religious scruples against

capital punishment, violates (in general, or in the partic-

2

nlar forms presented here) the Constitution of the United

States. That question is one of first impression in the

Court.6 We shall urge that it not he decided on the merits

at this time, on these records.

In Witherspoon, the Court reviews the denial by the

Supreme Court of Illinois of the relief sought in a state

collateral attack proceeding against a conviction of murder

and sentence of death. Among the claims presented by

Witherspoon in his post-conviction petition was the conten

tion that his trial jury was unconstitutionally composed,

because the trial court excluded from it persons scrupled

against the death penalty. Under the dictates of an Illinois

statute in effect at the date of the trial,7 47 prospective

6 Although one of the several qualifying screens employed to select the

blue ribbon jury challenged in Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947),

was the exclusion o f death-scrupled jurors, no distinct issue was made

in this Court of the validity of such an exclusion. Fay, which closely

divided the Court on other, tangentially related issues, cannot therefore

be thought seriously to address the point. The only other consideration

of the question by the Court that we have discovered is a nineteenth

century opinion, Logan v. United States, 144 U.S. 263, 298 (1892).

Logan sustains the exclusion of scrupled jurors but reverses the convic

tion there appealed from on other grounds. It is not altogether clear

whether this decision, of Conformity Act vintage, states a rule of federal

or o f Texas practice, particularly since the substantive capital offense

charged in Logan was assimilated by R ev . S tat . §5509 (1875), from

Texas law. In any event, no constitutional issue was raised or addressed

by the Court, and the disposition of the case on the writ of error was

not affected by the Court’s discussion of the scrupled juror issue. In

Hardy v. United States, 186 U.S. 224, 227-228 (1902), the question

presented related to the form of voir dire examination allowed a prose

cutor inquiring about scruples. No question of the allowability o f a

challenge for cause was raised.

7 III . R ev. S tat ., 1959, Ch. 38, §743: “ In trials for murder it shall

be a cause for challenge of any juror, who shall on being examined,

state that he has conscientious scruples against capital punishment, or

that he is opposed to the same.” This provision, in effect at the time of

Witherspoon’s trial, was not reenacted in the new Illinois Code of Crim

inal Procedure effective January 1, 1964; but the practice of death-

qualifying a capital jury has been sustained under the new Code, as au

thorized by the general section providing that each party may challenge

jurors for cause. People v. Hobbs, 35 I11.2d 263, 220 N.E.2d 469 (1966).

3

jurors (out of a total of 96 examined on the voir dire) were

excused at the request of the prosecution or routinely by

direction of the court because they were conscientiously

opposed to capital punishment. As is usual in such cases,

the specific questions asked of the veniremen regarding

their attitudes toward the capital penalty, answers to which

were treated as requiring their exclusion, varied from

venireman to venireman. Most were excused summarily,

without further inquiry upon their affirmative response to

the question whether they had any conscientious or religious

scruples against the infliction of the death penalty, or

against its infliction “ in a proper case.” 8 A few were asked

whether they could vote to inflict the death penalty in any

case.9 Some were asked whether they “believed in” the

death penalty.10 A couple were cross-questioned by the

court as to whether their profession of scruples was sincere,

or whether they “ just want to get off the jury.” 11 A few

other forms of inquiry appear.12 Only one of the 47 jurors

excluded for scruples was asked whether he could return

a guilty verdict; and this was an ambiguous question, put

to a confused venireman together with other questions on

the subject, and apparently not the critical question whose

8 See the imprinted record of the voir dire proceedings in Witherspoon

(hereafter, Witherspoon T r . ------ ) 661, 662, 668, 686-687, 723-724, 729,

730, 739, 743-745, 752, 788, 806, 807, 823-824, 830, 841-842, 857, 868, 877,

892, 893, 1017, 1018. Approximately three-fifths of the 47 jurors ex

cused for scruples were simply asked whether they had any conscientious

or religious scruple against the infliction of the death penalty in a proper

case, and answered that they did. Another fifth responded affirmatively

to the same question modified by the omission of the words “ in a proper

ease.” The remaining fifth of the excluded jurors were asked other or

additional questions.

9 Witherspoon Tr. 685, 714-715, 944, 991.

10 Witherspoon Tr. 847-848, 856-857, 868; see also id., at 841-842.

11 Witherspoon Tr. 744-745; see also id., at 685-686, 824, 990-991.

12 Witherspoon Tr. 644, 685-686, 990-991.

4

answer resulted in Ms exclusion.13 In all, it is fair to say

that on the Witherspoon voir dire, no inquiry was made

by the prosecution or the court to determine whether the

direction or strength of a venireman’s scruples was such as

to preclude his convicting the defendant of murder in a

proper case; and only a minority of the excluded jurors

were even asked whether their scruples were such as to

foreclose their voting for death on the facts of a particular

case, if ordered by the court to consider that penalty as one

available alternative. In a manner typical of many capital

trials (under varying statutory provisions in the several

jurisdictions), prospective jurors opposed to capital pun

ishment were simply identified as in some general fashion

opposed, and were thereupon expeditiously dispatched. The

pattern was set early in the voir dire by the judge: “Let’s

get these conscientious objectors out of the way, without

wasting any time on them. Ask him that question first.”

(Witherspoon Tr. 666; see also id., 661, 668, 687-688, 944).

That procedure was generally followed thereafter.

The jury selected by this process convicted Witherspoon

and sentenced him to death. His conviction and death sen

tence were affirmed on appeal, and after some intervening

post-conviction litigation, the present petition was filed

raising inter alia the claim that exclusion of scrupled jurors

violated the federal Constitution. The petition was accom

panied by an express request to introduce evidence in sup

port of its contentions. The post-conviction trial court sua

sponte denied this request and dismissed the petition. The

Supreme Court of Illinois affirmed, People v. Witherspoon,

36 111. 2d 471, 224 N.E. 2d 259 (1967), relying for rejection

of the scrupled-juror contention largely on its recent deci

sion in People v. Hobbs, 35 111. 2d 263, 220 N.E. 2d 469

(1966), a case coming to that court on direct appeal from a

13 Witherspoon Tr. 642-644.

5

murder conviction in which the death penalty had not been

imposed.

Bumpers brings here for review a judgment of the Su

preme Court of North Carolina affirming on direct appeal

convictions of Bumpers on a bill of indictment for rape (a

capital charge) and two bills for assault with intent to kill.

Pursuant to the jury’s recommendation of mercy, Bumpers

was sentenced to life imprisonment on the rape conviction;

consecutive ten-year terms were imposed on each conviction

of assault. In the process of selecting the trial jury, 53

? veniremen were interrogated; 16 were excused on the prose

cution’s challenge for cause because of opposition to capital

punishment, including 3 of the 6 Negro veniremen.14 De

fense counsel was allowed by the court a blanket objection

on federal constitutional grounds to this death-qualification

procedure.15 As in Witherspoon, the disqualifying questions

asked the several veniremen varied but none touched on the

'./prospective jurors’ ability or willingness to bring in a guilty

(verdict. Several of those excused asserted that they could

not vote for the death penalty under any circumstances.16

Several admitted that they did not believe in capital punish

ment under any circumstances.17 One said only that he did

not believe in capital punishment.18 Another admitted that

he had conscientious or religious scruples against the death

penalty.19 One juror said that he would not want to give

14 Bumpers R. 71-72. Bumpers is a Negro charged with rape o f a

white woman and assaults upon the woman and her white escort. The

remaining three Negro veniremen were also excused, one for cause and

two on the prosecutor’s peremptory challenges.

16 Bumpers R. 14 (stating the ground of objection), 16 (allowing the

general objection).

16 Bumpers R. 13-14, 15, 18-19; ef. id. at 16, 17.

17 Bumpers R. 17, 19, 20.

18 Bumpers R. 19.

19 Bumpers R. 16.

6

consideration to the death penalty as a possible verdict, bnt

that he would consider it if the judge told him that he was

required to ; he would obey the court. The judge then asked

him “Do you believe in capital punishment” ; he answered

no; and he was excused.20 A final juror testified that he

believed in capital punishment, but not for rape; that he

would not therefore consider a verdict of guilty as charged

(i.e., without recommendation of mercy) in this rape case.

The judge asked: “You do not believe in capital punish

ment in rape cases, is that what you said?” The juror re

plied that that was correct, and was excused.21 These pro

ceedings were had and excuses allowed, pursuant to a set

tled North Carolina practice that is, apparently, without

express statutory authority.22 The State Supreme Court

sustained its validity in affirming Bumpers’ convictions,

State v. Bumpers, 270 N.C. 521, 155 S.E.2d 173 (1967), in

reliance upon a recent decision to the same effect in an ap

peal of a case wherein the death penalty had been imposed,

State v. Childs, 269 N.C. 307,152 S.E.2d 453 (1967).

The death-qualification procedures disclosed by these two

records are exemplifications of a practice, common in its

general forms but varying widely in the details of its execu

tion, from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The exclusion of

scrupled jurors from capital juries is forbidden by judicial

decision in one state,23 and by recent statutory enactments

20 Bumpers R. 15.

21 Bumpers R. 19.

22 The only applicable North Carolina statute appears to be N.C. G e n .

Stat . §9-14 (1953 Reeomp. Yol.), preserving in general terms “ the usual

challenges in law to . . . any juror,” and providing that the judge shall

“ decide all questions as to the competency of jurors.”

23 State v. Lee, 91 Iowa 499, 60 N.W. 119 (1894); State v. Rocker,

138 Iowa 653, 116 N.W. 797 (1908); State v. Wilson, 234 Iowa 60, 11

N.W.2d 737 (1943). In State v. Garrington, 11 S.D. 178, 76 N.W. 326

(1898), the South Dakota Supreme Court also held the excuse of scrupled

jurors improper, but subsequent legislation allowed it. S.D. Rev. Stat.

§34.3618(10).

7

in two more ;24 elsewhere in this country, it is practiced in

varying forms under statutory provisions or common-law

criminal procedure.25 It appears not to be practiced in

England (prior to the advent of abolition),26 in Canada, or

in other common-law jurisdictions.

The questions asked veniremen to determine the state

of their conscientious or religious attitudes toward capital

punishment, and the precise grounds of disqualification

Tor scruples, vary widely. From State to State, from

\court to court, from judge to judge, from case to case,

.and even from venireman to venireman on a particular

'ftoir dire (as in Witherspoon and Bumpers), interrogation

of the veniremen may be more or less protracted and

intensive; and excuses are allowed on answers ranging

from a flat assertion that the juror would never convict

on any state of facts in a case where the death penalty

is possible, to a generally expressed opposition to capital

punishment, or approval of its legislative repeal, or a

statement that only in an extreme case would the juror

impose the penalty of death.27 Cases with which we are

24 Md. Code A nn ., Art. 51, §8A (1967 Cum. Supp.); 1967 Nev. Ses

sion Laws p. 1472, repealing former Nev. Rev. Stat. §175.105(9),

26 See Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital Cases, 101

U. Pa . L. Rev. 1099, 1105-1107 (1953); Annot., Beliefs Megarding

Capital Punishment as Disqualifying Juror in Capital Case for Cause,

48 A.L.R.2d 560 (1956). The practice is criticized in Oberer, Does Dis

qualification of Jurors for Scruples Against Capital Punishment Consti

tute Denial of Fair Trial on Issue of Guilt, 39 Texas L. Rev. 545 (1961)

[hereafter cited as Oberer]; Oberer, The Death Penalty and Fair Trial,

The Nation, vol. 198, No. 15, p. 342 (April 6, 1964); McClelland, Con

scientious Scruples Against the Death Penalty in Pennsylvania, 30 Pa.

Bab A ssn. Q. 252 (1959).

26 Oberer, at 566, 7, n. 92.

27 See, for example, the excerpts of voir dire in the Arguello case,

s.et forth in Appendix I infra. See also, e.g., State v. Scott, 243 La. 1,

141 So.2d 389, 394 (1962) (sustaining exclusion of a juror whose ex

pressed attitude was “ that the offense would have to be 'pretty serious’ for

8

familair show a great variety in the level of concern of

the voir dire procedure with the question of conscientious

scruples. In many instances, the presiding judge routinely

and without much inquiry identifies veniremen who say

that they oppose capital punishment, or whom the judge

believes have some reason for opposing it, and excuses

them summarily. (We know of one capital case, for ex

ample, in which a prospective juror was excused simply

because he was a Quaker.)28 In other proceedings, hours

of questioning are devoted to the jurors’ attitudes toward

capital punishment. Lengthy and elaborate interrogation

of the veniremen is pursued, whose effect is to leave with

the jurors the intense impression that conscientious

scruples and attendant attitudes of mercy and compassion

j are unlawful, irrational, and the fit subject of judicial

(condemnation. (We are aware, for example, of an instance

in which a prospective juror who reacted to a protracted

death-qualifying voir dire by volunteering that she had

two sons of her own, and, thinking that it might be one

of them on trial, might favor the defense, was excused

from jury service generally—not merely in the capital

case being tried—for the announced reason that, she was

emotional, hence unfit for jury service).29

him to bring in a verdict assessing the death penalty . . . ” ). Compare

State v. Weston, 232 La. 766, 95 So.2d 305 (1957) (sustaining the inclusion

of a juror whose expressed attitude was that he would always impose

the death penalty except where the evidence was pretty weak). Some

jurisdictions that allow the exclusion of jurors scrupled against capita]

punishment also excuse for cause jurors scrupled in favor o f the

death penalty. E.g., State v. Henry, 196 La. 217, 198 So. 910 (1940).

Others do not. E.g., Hollins v. State, 148 So.2d 274 (Pla. 1963); see

Poole v. State, 194 So.2d 903 (Fla. 1967).

28 See the excerpt o f voir dire examination in the Saterfield case, set

forth in Appendix II, infra.

29 See the excerpt o f voir dire examination in the Schader case, set

forth in Appendix III, infra.

9

We have gone outside the records of Witherspoon and

Bumpers for this brief description of the general institu

tion of death-qualification of capital juries, as it is prac

ticed in the several States today, because the Court’s deci

sion in these cases may affect the institution more or less

broadly, and it seems advisable that the nature of that

somewhat amorphous institution, in its general outlines,

be stated.

Summary o f Argument

We urge that the Court not now decide on the merits

the ultimate constitutional question posed in these two

cases: whether death-qualifying a capital jury violates

the Constitution of the United States. The Witherspoon

case should be reversed and remanded with directions

to afford Witherspoon the evidentiary hearing which his

post-conviction petition sought in order to substantiate

that federal constitutional claim. This may and should

be done without deciding the substantive validity of the

claim, since one of the purposes for which Witherspoon

sought a hearing was to make a record of constitutional

facts— as distinguished from adjudicative facts—facts

whose very function is to support an advised and well-

considered determination of the merits of the constitutional

question to which they relate. The scrupled-juror issue

need not and ought not be reached in Bumpers, since

Bumpers has a palpably valid search-and-seizure claim

that is included within the grant of certiorari to the Su

preme Court of North Carolina; but, if it is reached,

Bumpers should fitly be remanded to that court in light of

the reversal of Witherspoon.

Our reasons for urging deferment of decision upon the

constitutional objections here presented to the practice

10

of excluding death-scrupled jurors from capital juries

are several. First, the scrupled-juror question is one of

vital importance—literally a question of life or death—•

to hundreds of condemned men on whose behalf proceed

ings raising the point are already pending in a number

of courts. Those proceedings present the scrupled-juror

question in the context of several other substantial federal

constitutional contentions, not brought here in Witherspoon

and Bumpers, which are so functionally related to the

scrupled-juror issue that decision of the latter without

consideration of them would be exceedingly ill-advised.

Second, the nature of the scrupled-juror issue itself is

such that an adequate factual record, not presented to

the Court by either of these cases in their present posture,

is the indispensable condition of its wise and deliberate

decision. More even than most constitutional issues, the

claim that due process and equal protection are violated

by the exclusion of death-scrupled jurors implicates ques

tions of constitutional fact which the Court cannot prop

erly resolve by intuition or speculation, and whose de

velopment on the record of an evidentiary hearing is

essential to informed and enlightened determination of

this difficult, important constitutional point.

Those factual questions are of a sort that lend them

selves to systematic investigation by the methodology of

social science research; and, indeed, a major empirical

study of them has already been undertaken whose results

can be judicially presented in a fashion that will illuminate

the ultimate constitutional judgments required to be made.

Since Witherspoon was wrongly denied an evidentiary

hearing at which this sort of presentation could be de

veloped, proper principles for the adjudication of grave

constitutional controversies require the reversal and re-

11

mandment of his case. The same principles preclude un

necessary and precipitous disposition of the issue in

Bumpers, which is properly reversible on another ground.

If, however, the scrupled-juror point is reached in

Bumpers, that case should be remanded without definitive

decision of the constitutional merits because of (i) unclarity

of the record stemming from the ambiguous treatment so

far given by the North Carolina Supreme Court to matters

of the sort that will be heard after remand in Witherspoon

and (ii) the desirability of affording the North Carolina

court an opportunity for determination in the first instance

of the issues presented here, cf. Patterson v. Alabama, 294

U.S. 600 (1934).

12

ARGUMENT

I.

This Court Should Not Decide the Serupled-Juror

Issue in Isolation From Other Related, Substantial Fed

eral Constitutional Challenges to Capital Trial Pro

ceedings.

A. The Scrupled-Juror Issue in Context.

As we have indicated in our motion for leave to file

this Brief, pp. 1-M-6-M, supra, we are now representing a

substantial number of the condemned men in this country.

On their behalf, we have raised a set of interrelated

federal constitutional challenges to capital punishment and

to its common procedural incidents which several courts,

including this Court, have recognized as substantial.30

30 The following litigations are noteworthy, although the enumeration

is not exhaustive:

(i) Adderly v. Wainwright, U.S.D.C., M.D. Fla., No. 67-298-Civ-J is

a class action habeas corpus proceeding on behalf o f the 50 inmates of

Florida’s death row, challenging the administration of capital punish

ment in that State on the first four grounds stated at pp. 20-21, infra.

(For purposes of this footnote, those grounds may be abbreviated as:

(1) exclusion of scrupled jurors; (2) lawlessly broad jury discretion;

(3) unconstitutional single-verdict procedure; (4) cruel and unusual

punishment. The fifth ground described at p. 21, infra—racial dis

crimination in capital sentencing— is not presented in Adderly, but is

raised in another habeas corpus case in the same court, Craig v. Wain-

wright, U.S.D.C., M.D. Fla., No. 66-595-Civ-J, pending.) In an order

of April 13, 1967, in the Adderly ease, United States District Judge

William A . McRae, Jr. stayed all executions in the State of Florida,

reciting that “ it is apparent on the face of the Petition that if peti

tioners’ allegations are true, their constitutional rights may have been

violated . . . [A]side from the procedural aspects of the case [involving

the propriety of a class action for a writ of habeas corpus], the peti

tion, taken as a whole, may state a claim for relief by way of federal

habeas corpus.” (Order of April 13, 1967, pp. 1-2.) By order o f August

9, 1967, Judge McRae subsequently continued his class action stay in

effect. (footnote continued on next page)

13

The Witherspoon and Bumpers cases present one of those

(ii) Hill v. Nelson, U.S.D.C., N.D. Cal., No. 47318, is a similar class

action habeas corpus proceeding on behalf of California’s 60 condemned

men. It raises the same claims as Adderly, with the exception of the

single-verdict contention. (California has a split-verdict procedure for

capital trials in murder cases.) By order of July 5, 1967, District Judge

Robert F. Peekham stayed all executions in California for which dates

had been or would be set. The Attorney General of the State sought

by a petition for mandamus and prohibition to have the Court of Ap

peals for the Ninth Circuit set aside Judge Peckham’s stay. The Court

o f Appeals declined, after argument, to do so. Nelson v. Peekham, 9th

Cir. No. 21969, decided July 10, 1967.

Thereafter, Judge Peekham determined that considerations of con

venience were persuasive against entertaining the Hill v. Nelson case as

a class action. By order of August 24, 1967, he therefore vacated the

class stay, but kept the stay in effect as to the individual Hill petitioners.

Exercising the authority of a federal habeas corpus court to “ dispose of

the matter as law and justice require,” 28 TJ.S.C. §2243 (1964), he

established a procedure for the filing o f individual federal habeas corpus

petitions by the other death-sentenced California prisoners, for their con

solidation, and for stays of execution of the individual petitioners. “ Jus

tice requires that no condemned man who has standing to raise any

federal constitutional issue, including any of the four common questions

[i.e., cruel and unusual punishment; lawlessly broad jury discretion;

exclusion of scrupled jurors; and a fourth claim—right to appointment

of counsel in the post-appeal stages of a capital case] should be executed

until such question is finally adjudicated.” (Order of August 24, p. 8).

(iii) United States ex rel. Smith v. Nelson, U.S.D.C., N.D. Cal. No.

48011, is an individual habeas corpus aetion raising the same issues as

Hill v. Nelson. The petition was denied on the merits by District Judge

William T. Sweigert on October 20, 1967. Judge Sweigert found the

issues presented substantial and accordingly granted a certificate of prob

able cause and a stay o f execution pending appeal. Thereupon, on

Smith’s motion in the appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

vacated Judge Sweigert’s Order denying the petition and remanded the

case to the District Court to await further developments in the California

Supreme Court cases described in the following subparagraph. Smith

V. Nelson, 9th Cir., No. 22328, Order o f January 3, 1968.

(iv) In the Hill v. Nelson order of August 24, Judge Peekham found

that several o f the federal issues raised therein had not been presented

to the California courts. He therefore required the individual Hill peti

tioners to exhaust their state remedies, while the federal stay o f execu

tion remained in effect. Habeas corpus petitions raising the four Hill

questions were filed in the California Supreme Court by two of the

Hill petitioners. By order of November 14, 1967, that court swa sponte

entered orders in Application of Saterfield Cal. S.C., Crim. No. 11573,

and Application of Anderson, Cal. S.C., Crim. No. 11572, staying all

14

challenges, isolated by the fortuities of litigation from the

others.81

executions of condemned men in the State of California until the issues

were resolved.

(v) The United States Court o f Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has

recently stayed executions o f individual federal habeas corpus petitioners

in cases challenging the administration of the death penalty in three

States within that Circuit. Spencer v. Beto, 5th Cir. No. 25548, Order

o f November 16, 1967 (Texas) ; Brent v. White, 5th Cir. No. 25496,

Order of November 28, 1967 (Louisiana); Shinall v. Breazeale, 5th Cir.

Misc. No. 978, Order o f February 21, 1968 (Mississippi). Bach of these

cases raises the four Adderly issues; Brent and Shinall also raise claims

of racial discrimination in capital sentencing and of systematic exclusion

of Negroes from the capital trial juries.

(vi) Stays of execution of condemned men have been issued by nu

merous federal district courts and state trial courts in post-conviction

proceedings raising the Adderly issues together with, in some cases, the

contention of racial discrimination in capital sentencing. E.g., Bell v.

Patterson, U.S.D.C., D. Colo., No. 67-C-458, Order of September 14,

1967; Segura v. Patterson, U.S.D.C., D. Colo., No. 67-C-497, Order of

October 13, 1967; Brown v. Lane, U.S.D.C., N.D. Ind., No. 4129, Order

of December 29, 1967; Childs v. Turner, U.S.D.C., W.D.N.C., No. 2663,

Order o f May 12, 1967; Chevallier v. Beto, U.S.D.C., S.D. Tex., No. 68-

H-57, Order of January 24, 1968; Arhwright v. Kelly, Super. Ct., Tatt

nall Cty., Ga., No. 5283, Order of December 1, 1967; Williams v. Kelly,

Super. Ct. Tattnall Cty., Ga., No. 5284, Order of December 1, 1967;

State V. Funicello, Essex Cty. Ct., N.J., Indictment No. 2049-64, Order

o f February 23, 1968.

(vii) Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967), is a habeas corpus pro

ceeding by a condemned Arkansas prisoner, challenging his sentence of

death on the grounds o f lawlessly broad jury discretion, racial discrimina

tion in capital sentencing, and unconstitutional single-verdict procedure.

His petition also raised a claim of systematic exclusion of Negroes from

Arkansas juries that had been decided against him on the merits in a

prior federal habeas proceeding. The district judge declined to enter

tain the jury claim anew, and decided the several capital punishment

issues against Maxwell on the merits. He declined to issue a certificate

o f probable cause or a stay of execution pending appeal; and a Circuit

Judge o f the Eighth Circuit also refused a certificate or a stay. Mr.

Justice White thereupon stayed Maxwell’s execution, and this Court

reversed and remanded with directions to grant a certificate and a stay.

The case is now under submission in the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit.

31 This isssue is sub judice in numerous other cases, in addition to those

noted in the preceding footnote. We are unable to provide an exhaustive

15

We urge the Court to view this issue in the contest of

the others. It is not our purpose, in so urging, to expand

the constitutional questions presented for consideration be

yond the limited ones raised by the grants of certiorari

here. To the contrary, the thrust of our submission is that

the Court should not decide even those limited issues on

the merits at this time. But, in order to understand what

is at stake in the challenge to exclusion of death-scrupled

jurors, and precisely why we contend that decision of the

scrupled-juror issue had best he deferred for decision on

fuller records than are now before the Court, it is impera

tive to see the procedures for the trial of capital cases as

an inter-connected functioning system, subject—in the to

tality of their operation—to a number of similarly inter

connected, grave federal constitutional complaints. Such

a perspective is essential, we suggest, to informed delib

eration upon the constitutional implications of the one

aspect of that system, the practice of death-qualifying cap

ital juries, now before the Court.

The full range of interrelations among those federal

constitutional grievances that arise from the common

forms of capital trial practice is not immediately evident.

We explore the principal aspects of relationship at pp.

22-28 below, following identification of the substance of

the several grievances. But, at one level, the interrelated-

ennmeration, but the following litigations are exemplary of the eases

pending at every level of the state and federal court systems: Wheat

v. Washington, U.S., Misc. No. 1301 (petition for certiorari pending);

Ellison V. Texas, U.S., Misc. No. 1311 (sam e); Evans v. Button and

Williams v. Dutton, 5th Cir., Nos. 25348-25349 (pending for decision of

the scrupled-juror question); Clarke V. Grimes, 374 F.2d 550 (5th Cir.

1967) (execution stayed pending exhaustion of state remedies on the

issue); Crain v. Beto, U.S.D.C., S.D. Tex., No. 66H-626 (pending for

decision of the issue) ; State v. Smith and State v. Biggins, Wash. S.C.,

Nos. 39475, 39481 (pending for decision of the issue); Siros V. State,

Dist. Ct. Harris Cty., Tex., No. 104617 (habeas corpus petition pending

for decision of the issue).

16

ness of the grievances is intuitively obvious. "What is at

issue in these capital cases is the fundamental question of

the fairness and regularity required by the Constitution in

proceedings by which the State determines to take human

life.

The cases confront squarely both the procedure and the

practical consequences of the procedure used to make the

legal decision whether a man should live or die. In a capi

tal ease tried in most jurisdictions in this country—includ

ing Illinois and North Carolina—that procedure consists

of death-qualifying a jury by systematically excluding

from it persons representative of the most enlightened seg

ment of public opinion, and committing to the jury so

selected a wholly arbitrary and unregulated discretion in

the life-death choice, to be exercised under conditions that

deprive the jurors of information that is the indispensable

requisite of rational sentencing judgment.

B. A Summary o f Capital Trial Procedure.

Specifically:

(1) On voir dire examination, persons having con-

/"~scientious or religious scruples against capital punish-

I ment are excused for cause. The immediate effects of

! this practice are several. First, it indirectly achieves

• what the States are forbidden directly to achieve: the

systematic limitation of racial and other minority

groups and of women—populations disproportionately

characterized by death scruples. Second, it delivers

over the administration of justice in trials for the most

serious crimes known to our society, bearing the most

serious penal exaction that human society can levy

upon a defendant, to an unrepresentative sub-group

of the community, comprising its most punitive, ata

vistic and uncompassionate members. Third, in the

17

process of voir dire questioning by which the jury is

death-qualified, it reinforces the very attitudes of

punitiveness and uncompassion by which the jurors

allowed to serve are natively characterized, driving

home the message that any principled, ideologically-

derived determination against the death sentence for

the offense on trial is forbidden to the jury, and, in

deed, that the attitudes of mercy and compassion

which may undergird such a determination are legally

disfavored and morally unfit.

f" (2) The capital case is then tried to the jury so se

lected, which determines both the question of guilt

and that of punishment. Ordinarily, these two deter

minations are made simultaneously—by the traditional

“ single-verdict” procedure, as distinguished from the

two-staged, “ split-verdict” procedure used in a hand

ful of jurisdictions. Under this single-verdict proce

dure, the jury hears all the evidence bearing on guilt

or on punishment before retiring to decide the guilt

question, then returns with a single verdict which ad

judges guilt or innocence and fixes the punishment for

guilt at death or something less. There is no separate

hearing on the question of sentencing, and no oppor

tunity—other than the guilt trial—to present to the

jury evidence of the defendant’s character and back

ground, pertinent to the death-life choice. At the guilt

trial, the prosecution is usually forbidden to open up,

in its case in chief, matters relating to the defendant’s

character and background. The defendant may open

up the character question, subject to rebuttal by pros

ecution evidence of bad character, damningiy preju

dicial on the guilt determination. And, of course, the

defendant may make an appeal for mercy in sentenc

ing, may personally address those persons who hold

18

his life in their hands, only by taking the stand gen

erally, thereby waiving the privilege against self-

incrimination. This is a practice that, as the Reporters

of the A.L.I. Model Penal Code, have noted, forces the

defendant to a “ choice between a method which threat

ens the fairness of the trial of guilt or innocence and

one which detracts from the rationality of the deter

mination of the sentence.” 82 For present purposes,

what is important is that a defendant who believes he

has any chance of acquittal of a capital charge will

often choose to avoid prejudicing that chance by ex

pansion of the trial record into background and

character matters that can make him appear guilty;

and, under single-verdict procedure, the result fre-

C quently is that capital sentencing is done by a jury

that knows next to nothing about the person of the

defendant, and has not even heard him speak in favor

.of his life.

\ (3) But the jury is not merely deprived of factual

information that is essential to rational sentencing

choice. It is also deprived of any sort of legal stand

ards or guidelines for making that choice. Under

ubiquitous capital trial procedure—in Illinois and

North Carolina, as in virtually every other American

jurisdiction—the decision between the death penalty

and lesser alternatives to it is required to be made by

the jury in its unguided, unfettered and unreviewable

discretion—according to whatever whims or urges may

move it. This most momentous of human decisions is

unlike any other made by a jury in a purportedly legal

proceeding: it is not made pursuant to rules of law

or within the limitations of any sort of regular, uni- 32 *

32 A m erican Law I n stitu te , M odel P en al C ode, Tent. Draft No. 9

(May 8, 1959), Comment to §201.6, at p. 74.

19

form or generalized doctrines or principles. Rather it

is avowedly ad hoc, ex post facto and— because it nei

ther does nor need respond to any rational conception

of punishment or sanctioning—wholly arbitrary. Little

wonder that, in the actual administration of capital

sentencing, jurors have been shown to use this lawless

discretion lawlessly, and to discriminate racially, for

example, in sentencing men to death.38

(4) The jury’s sentencing decision is not ordinarily

'' judicially revisable. It is, of course, subject to corree-

I • tion by the exercise of executive clemency; but this

| s sort of gubernatorial dispensation is administered still

more irregularly than the jury’s decision itself. Pro

cedures for the clemency determination are unformu

lated; standards to guide it are non-existent; and, by

this stage, the condemned man is usually unrepre

sented and legally helpless.33 34 Political and other con

siderations nevertheless do bring about a substantial

number of commutations; and, at the conclusion of the

process of a Nation’s administration of capital justice

for any year, only a few random, arbitrarily selected

men are legally put to death. Their executions are as

futile and purposeless as they are unusual and arbi

trary. For, although it is impossible to speak with

dogmatic assurance in such matters, there is simply

no evidence that capital punishment serves any legit

imate end or purpose of the criminal law—deterrence,

incapacitation, reformation—which lesser exactions do

not; and the very strong weight of expert opinion

condemns the death penalty as utterly without redeem

ing social value.

33 See text and notes at notes 1, 2, supra.

34 See text and note at note 4 supra.

20

C. The Federal Constitutional Violations Entailed

by the Procedure.

The specific federal constitutional attacks which appear

to us to be validly leveled against the various aspects of

the procedure just described— and which are raised in most

of the litigations described in footnote 30 supra— are the

following:

C (1) The systematic exclusion of death-scrupled ju

rors in capital cases offends the Constitution because

(i) it deprives capital defendants of trial by a jury

that is a cross-section of the community, in violation

of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment; and (ii) it results in a

biased and prosecution-prone jury, unable to accord

the defendant a fair trial on the issue of guilt, in

violation of the Due Process Clause.

^ , (2) The ubiquitous practice which commits sentenc

ing decision in capital cases to the undirected, unlim

ited and unreviewable discretion of the jury, permit

ting jurors to choose between life and death arbitra

rily, capriciously, for any reason, or for no reason,

violates the rule of law basic to the Due Process

Clause, for reasons akin to those that determined

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966).

(3) The single-verdict procedure whereby a trial

jury in a capital case simultaneously hears evidence

pertinent to guilt and to sentencing, and returns a

single verdict speaking to both issues, is constitution

ally deficient because (i) it compels the defendant to

a choice between his constitutional rig'ht of allocution

(and to present evidence prerequisite to rational sen

tencing choice) and his privilege against self-incrimi

nation, and (ii) it results in an unfair trial on either

the guilt issue, or the sentencing issue, or both.

21

(4) Capital punishment is a cruel and unusual pun-

isment within the condemnation of the Eighth Amend

ment as incorporated into the Fourteenth, at least

where (i) the life-death choice is committed to the un