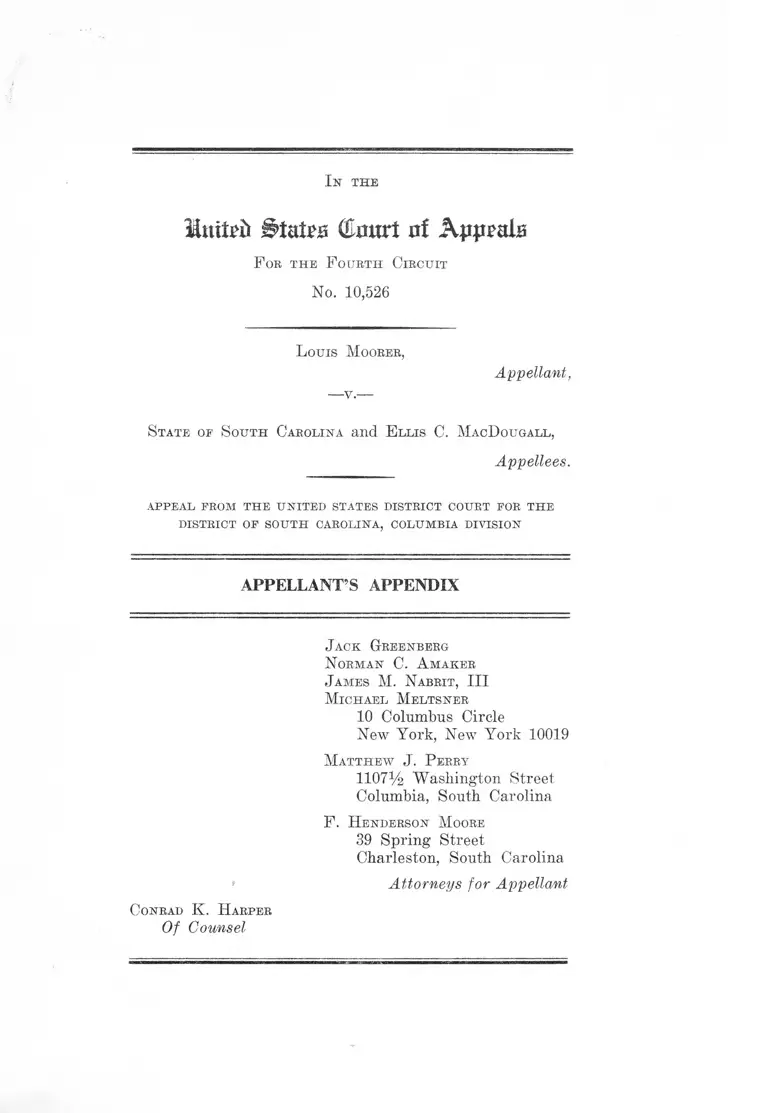

Moorer v. South Carolina Appellant's Appendix

Public Court Documents

August 18, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moorer v. South Carolina Appellant's Appendix, 1965. 205198ae-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95860da4-5e06-40d6-bd55-da3813371848/moorer-v-south-carolina-appellants-appendix. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

Gkwrt of Appeals

F or the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,526

Louis Moorer,

■V.

Appellant,

State oe South Carolina and E llis C. MacDougall,

Appellees.

A P PE A L PROM T H E U N IT E D STATE S D ISTR IC T COURT FOR T H E

D ISTR IC T OF S O U T H CARO LIN A, C O LU M B IA DIVISION

APPELLANT’ S APPENDIX

Jack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Matthew J. P erry

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

F. Henderson Moore

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellant

Conrad K. H arper

Of Counsel

INDEX

Page

Petition for Leave to Proceed in Forma Pauperis.... 1

Affidavit of Louis Moorer in Support of Petition... 2

Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus.............. 4

Motion for Leave To File Amended Petition for Writ

of Habeas Corpus........................... . 9

Amended Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus........ 10

Decision and Order by Haynsworth,Jr. dated May 13,

1965, staying execution of death sentence...... 19

Decision and Order of U. S. Court of Appeals for

the '4-th Circuit dated June 23, 1965 Vacating

Order Dismissing Habeas Corpus Application......22

Order ■'of U.S.District Court, E.D. of South Carolina

dated July 6 , 1965 staying execution of death

sentence....................................... 25

Pre-Trial Order............................... 26

Motion to Withdraw Petitioner's Exhibit 1 To Make

Photostatic Copies Thereof..................... 30

Decision and Order of U.S. District Court, District

of South Carolina, Columbia Division dated

January 3, 1966 Denying Amended Petition for

Habeas Corpus...... 32

Motion for Rehearing................................51

Exhibit Annexed to Foregoing Motion - Preliminary

Analysis of Rape and Capital Punishment in

Louisiana - 194-5-1965...........................56

Exhibit Annexed to Foregoing Motion - Preliminary

Analysis. Louisiana Data. Tables I-XLIII....... 62

Exhibit Annexed to Foregoing Motion - Affidavit

of Dr. Marvin Wolfgang......................... . . 8 6

Certificate of Service of Motion for Rehearing///...90

Additional Affidavit of Dr.Marvin Wolfgang......... 91

Decision and Order of Hemphill, J., dated January

19,1966 Denying Motion for Rehearing............ 95

Notice of Appeal to U. S. Court of Appeals for 4th

Circuit.................... 95

Transcript of Record on Appeal in U. S. District

Court............................................ 97

Clerk's Gerti ficate 100

Transcript of Record in State of South Carolina

Supreme Court, Appeal from Dorchester County,

Griffith, J_............... 152

Verd let............ 152

Sentence...................................... 152

Except i on.................................... 1,55

Excerpts from Appendix - Charge to Jury..... J54

Verdict...................................... 1 .42

Transcript of Record in U. S.District Court for

Eastern District of South Carolina, Columbia

Division..................................... 145

Order Settling Record............................ 200

Transcript of Record in State of South Carolina

Supreme Court, Appeal from Richland County,

Grimball, J_.................. ................200

Testimony in South Carolina Supreme Court

Dorchester County

State's Witnesses:

Mrs. Catherin D. Johnston

Direct - 102

Mrs. Ethel Sharpe

Direct - 110

James M. Sharpe

Direct - 114

Dr. A. R. Johnston

Direct 117

Cross - 120

Wilson Wimberly

Direct - 121

Cross - 126

Sheriff Carl A. Knight

Direct - 126

Cross - 150

Ill

Testimony in United States District Court,

Eastern District of South Carolina, Columbia

Division

Petitioner's Witnesses: Page

John T. Major

Direct - 217

Testimony in South Carolina Supreme

Court,Richland County

Petitioner's Witnesses:

Cecil Merchant

Direct - 262

Cross -- 266

H. H. Walters,Jr.

Direct - 267

Cross - 274

Redirect- 275,277

Recross - 276

EXHIBITS

Petitioner's Exhibits in Tri&l in United States

District Court, Eastern District of South Carolina

1 For Identification - Box of Schedules.........214

2 For Identification - Schedule................. 226

w tm w i t w i m u u a n i o r m m t

mm imi s&srmm mwmict or momm ouhdliha

ootuMUA nsvxflxoci

LOUIS MOORER,

Petitioner,

-va-

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and

ELLIS C. M&cBOUGALL, Director,

South Carolina State Board of

Corrections,

)

)

)

)

)

)

Respondents. }

„_______________)

CIVIL ACTION

NO.

PETITION FOR LEAVE TO PROCEED IN FORMA PAUPERIS

Petitioner, Louis Moorer, who is now held

in the South Carolina State Penitentiary, at Columoia,

South Carolina, ask leave to file the attached Petition

for a Writ of Habeas Corpus to the United States District

Court for the Eastsrn District of South Caroline,Colombia

Division without prepayment of costs and to proceed in

forma pauperis. The petitioner's affidavit in support of

this petition is attachsd hereto.

F. HENDERSON MOORE

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

BENJAMIN L. COOK, JR.

43 Morris Strest

Charleston, South Carolina

MATTHEW J. PERRY

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

November 30, 1964. Attorneys for Petitioner. 1

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

COLUMBIA DIVISION

LOUIS MOORER,

Petitioner,

-vs-

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and

ELLIS C. MacDOUGALL, Director,

South Carolina State Board of

Corrections,

Respondents.

)

)

)

)

)

5

)

)

CIVIL ACTION

NO.

AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR LEAVE

TO PROCEED IN FORMA PAUPERIS

STATE OF SOOTH CAROLINA )

: SS .

OOUNTY OF RICHLAND )

I, LOUIS MOORER, being first duly sworn

according to law, deposes and say that I am the peti

tioner in the above entitled cause, and, in support of

my application for leave to proceed without being re

quired to prepay costs or fees, state:

1. I aa a citiaen of the United States.

2. Because of my provety I ass unable to

pay the costs of said cause.

3. I am unable to give security for same.

4. I believe I am entitled to the redress

I seek in said cause. 2

5. The nature of said cauaa is briefly

stated as follows:

I have bean convicted of the offense of

rape and sentenced to death. X an filing herewith a

Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus in which I contend

that my conviction violated the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution.

SWORN to before me this

_____ day of November, 1964.

LOUIS MOORBR

_____________________ ___________ (SEAL.)

Notary Public for South Carolina

3- 3

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

COLUMBIA DIVISION

LOUIS MOORER,

Petitioner,

-va-

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA end

ELLIS C. MecDOUGALL, Director,

South Caroline State Board of

Corrections,

)

)

)

)

)

)

Respondents. )

_________________)

CIVIL ACTION

NO.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF HABEAS OORPUS

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGES OF THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA;

The petition of Louis Moorer respectfully

shows to thi# Honorable Courts

1.

Petitioner is now unlawfully restrained of

his liberty at present in custody of Ellis C. MacDougall,

Director of the South Carolina State Board of Corrections

at the South Carolina State Penitentiary at 1515 Gist Street,

Columbia, South Carolina, in violation of the Constitution of

the United States of America, awaiting the infliction of

death (sentence electrocution against his will for the alleged

crime of rape.

4

2.

The fact* in connection with the aforesaid

detention and pending infliction of the death sentence

will be presented to this Court, including proceedings

originating out of the Court of General Sessions for Dor

chester County in the State of South Carolina, the Court

of Common Pleas for Richland County, South Carolina and

all proceedings before the Supreme Court of the State of

South Carolina and its decisions thereon.

3.

Upon the trial of petitioner in said Court

of General Session® for Dorchester County, State of South

Carolina, petitioner was convicted of the crime of rape

which judgment of conviction was, upon appeal to the

Supreme Court of the State of South Carolina, affirmed.

St*te v. Louis Moorer. 129 S.E.(2d) 330. Thereafter, a

petition was filed in the Court of Common Pleas for Richland

County, South Carolina for a Writ of Habeas Corpus which

petition was denied. The Supreme Court of South Carolina

affirmed the Order denying the Petition for Writ of Habeas

Corpus. Louis floorer v . State of South Carolina, etc., at

al., 135 S.B.(2d) 713. Thereafter, a petition was filed in

the Super®® Court of the United States for a Writ of Cer

tiorari which petition was denied October 12, 1964.

U.S._________ _ .

4,

Petitioner complained and complains that he

was not accorded a fair trial and begs leave to submit upon 5

-a-

th* hearing herein the records in the course of the pro

ceedings heretofore had in connection with the indictment

and conviction and the appeals therefrom wherein and where

from this Court nay be apprised of the contentions of

petitioner and petitioner prays that such records be deemed

to have been made a part of this petition by reference.

Petitioner further desires to present additional evidence

in support of his contention that his conviction in the

State Court violated the Constitution of the United States.

5.

Petitioner complained in his State Court

Habeas Corpus proceedings and complains here that th® indict

ment returned against him in Dorchester County, South Carolina,

was returned by a grand jury from which members of the Negro

race of which petitioner is a member, were and are systema

tically excluded or limited in number in violation of

petitioner's right to due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

6.

Petitioner complained in his State Court Habeas

Corpus hearing and contends here that the petit jury which

convicted him was drawn and convened in such a manner as to

exclude members of the Negro race, of which race petitioner

is a member, or to systematically limit in number their service

upon the petit juries of Dorchester County in violation of

petitioner'® right to process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

-3-

6

7.

Petitioner was convicted and sentenced to

daath for having allegedly viol*tad Section 16-71, Coda

of Law* of South Carolina for 1962, which statute is so

vague upon its face and by application to petitioner as

to offend the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution,

8.

Petitioner's sentence of death was imposed

pursuant to Section 16-72, Code of Laws of South Carolina

which statute is upon its face and aa applied to petitioner

under the circumstances of this case in violation of the

Constitution of the United States, in that!

(a) Said statute requires imposition of a

cruel, inhuman and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eight and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Con

stitution.

(b) Said statute denies petitioner the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

9.

Petitioner has now exhausted all remedies

before the Courts of the State of South Carolina.

10.

No previously application for the relief

sought herein has been made to this Court or any Judge r,

thereof.

-a-

Habeas Carpus, directed to Ellis C. MacDougall, Director

of South Carolina State Board of Corrections, by whoa

petitioner is detained and by whoa execution of petitioner's

sentence of death is ordered to be carried out, issue for

the purpose of inquiring into the cause of said imprisonment

and restraint and of delivering hia therefrom pursuant to

the statute in such cases made and provided.

WHEREFORE, petition** pray* that a Writ of

November 30, 1964. ________________________________

t. HENDERSON MOORE

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

BENJAMIN L. COOK, JR.

43 Morris Street

Charleston, South Carolina

MATTHEW J. PERRY

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner.

8

-5-

pern

ooummih m n m m

w w m memrn,

Pmtlti

>

)

)

)

st a t s or .s o u t h a m l i ma and

ELLIS C. NttcODCCALL. director, )

South Csrslla* &tmtm sk»*.rd a£

Corrections, )

CIVIL ACTION

NO.

JSttSpwMiMit*. }

1

NOTION PC'S L&AVB TO FILS. AMRMOK0 W I T M l

FOR WRIT OF liAIBAS 03RPW8

,»*t it loner Louis M M M t , respectfully *.v«»

the Court for lesvs to file th« «m c l >4 Attended Petit ia«*

far W i t of fishes# Carpus per asset to Title 31 U. S. C.

Section 5343.

'ley 13, IfPS.

M O M W J. r̂iSKV

1107% Washington Street

Colwnhi*, Couth Caro i ».«*

F. W * ® a » Q « Moose

Spring Street

Cheriest®*, South Caroline

amjutrut l . a x * , j«.

43. Norris Street

Charleston, South Caroline

Attorseye for .^titi otter

9

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT ODUET

FOR THE SASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

COLUMBIA DIVISION

LOUIS MOCKER,

Petitioner,

-vs-

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and

ELLIS C. MacDOUGALL, Director,

South Caroline State Board of

Correction*,

Respondenta.

CIVIL ACTION

NO.

AMENDED_PETITION.FOR WRIT OF HABEAS OORPUS

IT- THE HONORABLE ROBERT W. HEMPHILL, UNITED

STATES DISTRICT JUDGE;

The amended petition of Louis Moorer reapect-

fully shows to this Honorable Court;

l.

Petitioner ia now unlawfully restrained of his

liberty at present in custody of Ellis C. MacDougall,

Director of the South Carolina State Board of Corrections

at the South Carolina State Penitentiary at 1515 Gist

Street, Columbia, South Carolina, in violation of the

Constitution of the United States at Aeerica, awaiting the

Infliction of death sentence by electrocution against his

will for the alleged crime of rape.

10

TIM facts in commotion with the aforesaid

detention and pending infliction of thm dnnth eentence

will be presented to this Court, including proceedings

originating out of the Court of General Sessions for

Dorchester County in the State of South Carolina, the

Court of Common Pleas for Richland County, South Carolina

and all proceedings before the Supreme Court of the State

of South Carolina and its decisions thereon.

3.

Upon the trial of petitioner in said Court of

General Sessions for Dorchester County, State of South

Carolina, petitioner mi convicted of the crime of rape

which judgment of conviction was, upon appeal to the

Supreme Court of the State of South Carolina, affirmed.

State v. Louis Moorer, 129 S.E.(2d) 330. Thereafter, a

petition was filed in the Court of Common Pleas for Rich

land County, South Carolina for a Writ of Habeas Corpus

which petition was denied. The Supreme Court of South

Carolina affirmed the Order denying the Petition for Writ

of Habeas Corpus. Louis Moorer v. State of South Carolina,

®! *1•» 133 S.B.(2d) 713. Thereafter, a petition was filed

in the Supreme Court of the United States for a Writ of

Certiorari which petition was denied October 12, 1964.

U.S. ,13 L.Ed. 3d 63.

4 .

Petitioner complained and complains that he was

not accorded a fair trial and begs leave to submit upon the

2.

-2 11

hearing heroin tit* record* in th# course of tit# proceeding*

haret©fore bad in connection with tit# indictront and con

viction and tbs appeal* tb#r#from wheraia and wh#r#fro« this

Coart nay to# apprised of tit# cont«ntion* of petitioner and

petitioner px*ym that aach records to# deemed to have been

nad* a part of thia petition by reference. Petitioner

further deairaa to pr#a#nt additional evidence In support

of his contention that his conviction in th* Stat# Court

violated th* Constitution of the United States.

S.

Petitioner's restraint and detention violate

th* due process and equal protection clause* of th* Four

teenth Anendnent to the Constitution of th* United State*

in that he was indicted by a grand jury and convicted by a

petit jury from which members of the Negro race, of which

petitioner is a member, war# systematically and arbitrarily

excluded or limited in number:

a) Negro*# constitute in excess of 40 par

cent af the adult population of

Dorchester County.

b) Negroes constitute in excess of 10 per

cent of the registered voters in South

Carolina.

c) Negros# constituted only 6.7% of the

persons on grand juries in Dorchester

County between 1950 and 1963.

d) On 4 of the 9 petit jury venires drawn in

Dorchestar County between 1958 and 1963,

12

• ) On the § petit Jury v m i m drawn in

Dorchester County between 1*56 and

1*62, only 2.1* of the peracme drawn

wire Negro**, and no mare than 2

Megroea were placed on any petit jury

venire.

t) Between 1*48 and 1*62, no Negroee

actually aat on petit jariea in Dor-

cheater County.

g) The token mother of Negroee placed on

petit jury veairee are conaiatently

challenged or etricken, ao that Negroea

are prevented fro* earvice on petit

jttriea.

h) All jury c o m ! aaionera in Dor cheater

County are whit*.

i) Prospective juror* are choaan fron

voting regiatratlon liata which dealgnat*

the race of each voter.

6 .

Petitioner’a raatraint and detention violate* the

du* proceaa clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the united States in that he waa taken into

Court, at tha coananceneat of the tern of Court in which he

wee tried, end was subjactad to an arraignment proceeding on

m Negroes war* om the pttit Jury

15

April 3, 1962 without an attorney and was not advised by the

Court nor by any other official of the right to be represented by

an attorney during said arraignment proceeding or of the

right to consult with an attorney prior thereto. The arraign

ment of April 2, 1962 was a critical stage of the proceedings

in that it was a prerequisite to the validity of a waiver of

defendant's rights under Section 17-408, Code of Laws of

South Carolina for 1962, which allows a defendant to have a

copy of the indictment for three daye before being brought

to trial. Petitioner was tried on April 4, 1962, over

objection of counsel, less than three days after being pre

sented with a copy of the indictment. The Honorable John

Gri. inball, Judge of the Fifth Judicial Circuit, who denied

petitioner's petition for habeas corpus, erred in finding

that petitioner had counsel at his arraignment of April 2,

1962.

7.

Petitioner’s restraint and detention violates the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in

that petitioner was not given an accurate, unequivocal and

complete record of all proceedings in the Court of General

Sessions for Dorchester County preceding this conviction and

sentence of death.

8.

Petitioner's restraint and detention violates

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States in that he was subjected

to a preliminary hearing or some other pre-trial proceeding

14

-5-

without an attorney and without being advised of the right

to have an attorney present or of the right to consult with

an attorney prior to the commencement of said proceeding.

9.

Petitioner's restraining and detention violates

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States in that he was tried and

convicted of a capital offense, to wit: rape, and was at

no time given a true copy of the whole indictment against

him as is required by Section 17-408, Code of Laws of South

Carolina for 1962.

10.

Petitioner's restraint and detention violates the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States in that he was tried,

convicted and sentenced to death for having allegedly

violated Section 16-71, Code of Laws of South Carolina for

1962 which statute is upon its face and as construed and

applied to petitioner, vague, indefinite and uncertain.

11.

Petitioner has been deprived of due process of

law and the equal protection of the laws in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, in

that he was convicted without evidence of every essential

element of the crime, and in particular there was no evidence

of penetration.

12.

Petitioner wse deprived of due process of law and

the equal protection of the laws in violation of the

-6-

Fourteenth Amendment to the United State* Conatitution in that

the trial court allowed several witnesses to testify in the

presence of the jury that a voluntary statement had been taken

from the defendant soon after his arrest. This testimony was

highly prejudicial to defendant since it strongly suggested

that defendant had voluntarily confessed, and the issues of

admissibility of a confession must be decided before trial by

the court and out o . the presence of the jury.

13.

Petitioner's sentence of death was imposed pursuant

to Section 16-72, Code of Laws of South Carolina for 1963,

which statute is upon its face and as applied to petitioner

under the circumstances of this case, in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

in that:

a) Said statute authorises imposition of a

cruel, inhuman and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States.

b) Said statute denies petitioner equal protection

of the law and due process of law under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States in that there

has been an unequal application of said statute and in that

there is and has been a long standing practice, policy and

custom of sentencing Negro men to death for rape upon white

momen while not inflicting that punishment upon any other

per son.

-7- 16

14.

The constitutional claim raiaad in Paragraph 9

abova was raisad at petitioner's trial and passad upon adversely

to petitioner by tha Supr ema Court of South Carolina, affirm

ing the conviction. State v. Moore?. 241 S.C. 487, 129 S.E.

(2d) 330 (1963). The constitutional claims made in Paragraph

5, 6, 7 and 8 war® raised on petitioner's petition for habeas

corpus in the Fifth Judicial Circuit of South Carolina and

decided adversely to petitioner by that Court and by the

Supreme Court of South Carolina affirming the denial of habeas

corpus. Moorer v. State, S.C. ___ , 133 S.E.(2d) 713

(1964). The remaining constitutional claims herein set forth

were decided adversely to petitioner in an Order of the South

Carolina Supreme Court dated May 11, 1965.

15.

No previous application for the relief sought

herein has been made to this Court or any judge thereof.

WHEREFORE, petitioner prays that a Writ of Habeas

Corpus, directed to Ellis C. MscOougall, Director of South

Carolina State Board of Corrections, by whom petitioner is

detained and by whom execution of petitioner's sentence of

death is ordered to be carried out, issue for the purpose

of inquiring into the cause of said imprisonment and res

traint and of delivering him therefrom pursuant to *>e statute

in such cases made and provided.

May 12, 1965.

MATTHEW J . ‘PERRY

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

F. HENDERSON MOORE ^

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

-8-

BENJAMIN L. COOK, JR.

43 Morris Street

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

STATS OF SOUTH CAROLINA )

ss.

COUNTY OF RICHLAND )

PERSONALLY appeared before me Louis Moorer

who, on oath, deposes and says- That he is the petitioner

herein; that he has read the faregoing Amended Petition

for writ of Habeas Corpus and knows the contents thereof,

and that the sane ia true of his awn knowledge, except as to

the matters therein stated to be alleged upon information

and belief, and as to those matters he believes it to be

true.

LOUIS MOORER

SWORN to Da fore a*s this

day of .'say, 1965.

...... ....................... ..... . (SEAL)

Notary Public for South Carolina

18

-9-

‘U-.-V

F I LZ e nBHITED STATES COURT OF U m i l *“ ^

t o r r m fourth circuit MAY 1 31965

S o . 1 0 ,0 4 3 MAURICE S. DEAN

CLERK

Louis Mooiw,

varous

State of South Carolina and Bills C.

HacDougall, Director, South Carolina

State Board of Corrections,

Appellant,

Appellees.

Appeal fro® the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of South Carolina, at Charleston.

The appellant has applied to me for a stay of execution

of a sentence of death now scheduled to be executed tomorrow.

May 14, 1963.

The appellant has filed a proper notice of appeal frcm

an order entered in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of South Carolina on May 12, 1963, denying

an amended petition for habeas corpus. The motion for stay

is for the purpose of protecting the jurisdiction of the

United States Court of Appeals during the pendency of the

appeal.

The record on appeal discloses several proceedings in

the state courts, in Which there are a number of asserted

claims of denial of rights protected by the Constitution of

tha United States. The amended petition for corpus in

r. r

the District Court and tha earlier petition in that Court

sought relief upon those grounds. It further appears that

the District Court has not considered the constitutional

claims upon their merits. There has heea no evidentiary

hearing in the District court and. so far as now appears In

tha xeeord on appsal. no raviev in the District Court of the

state court proceedings to consider whether or not in the

state proceedings the federal claims have Dean fairly heard

and determined.

On their face. X cannot say that the federal constitutional

claims are frivolous or that the appeal is not without probable

merit. Indeed, the District drudge certified, for the purpose

of protecting the rights of the appellant, the existence of

probable cause to appeal.

Xn these circumstances, execution of the sentence would

effectively deny the right of appeal, and a stay of the

execution is essential for the protection of the jurisdiction

of the United States Court of Appeals to hear and determine

the appellant's rights in the premises.

There is also before me a petition of the appellant for

leave to proceed in forma pauperis, for the reasons stated

above. X have determined to grant the petition for leave to

proceed without prepayment of fees, to certify the existence

of probable cause to appeal, and to order a stay of the

execution pending the determination of the appeal is the

- 2 -

so

v. X.

United State® Court of Appeals fox the fourth Circuit.

It 28 n m p , therefore, that the appellant bo, and

ho io hereby permitted to prosecute his appeal la this

Court in the above entitled case in forma pauperis in

accordance with Title 2d, V.S.C., g 1915, without the pro-

payment of costs or the giving of security therefor*

FURTHER ORDERED that the Clerk of this Court file the

preliminary record on appeal and docket the appeal as of

May 13, 1965.

FOWHEft ORDERED, upon consideration of the petition

and pursuant to the authority under Title 23, U.S.C., f

2251, that the execution of the sentence of death imposed

by the Court of General Sessions of Dorchester County, State

of South Carolina, be, and the same is hereby, stayed pending

the termination of the appeal herein or the further order of

tha Court.

Clement 7. Haynsworth, Jr.

Chief Judge, Pourth Circuit

May 13, 1965

A. true copy,

T e s t e :

JlQUuUuu^ ̂

U. C^urt of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit

^ Clerk,

- J -

21

versus

f ■

State of South Carolina

| and Ellis C. MacDougall,

j.V; Director, South Carolina

I State Board of Corrections,

■i- ' ' ' ■„ . ■'t ■

JUN gs 1965

MAURICE S. DEAN

CUKK

Appellees.

; ;;

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of South Carolina, at Charleston. Robert W. Hemphill,

District Judge. j

■ '• . ' i' - . ■ ' • : • . I

Submitted

(Beeided ^ 3 1965.- Decided June 23, 1965)

• ' . i •

Before HAYNSWORTH, Chief Judge, and SOBELOPF and J. SPENCER

BELL, Circuit Judges.

Matthew J. Perry, F. Henderson Moore and Benjamin L. Cook,

Jr., on brief for Appellant, -.Daniel:'Ri McL&od* Att6rneyf)~..

General of South Carolina, counsbl fbr . Appellee.-,

\aigiJ

PER CURIAMJ

At issue before us on this appeal, which by agreement of the

parties has been submitted on brief, is the correctness of the

district judge's action on May 12, 1965, in dismissing an amended

petition for a writ of habeas corpus filed by Louis Moorer, a

Negro male who is currently awaiting death by electrocution pur

suant to a sentence imposed upon him by the Court of General

Sessions for Dorchester County, South Carolina, after his con

viction for rape on April 4, 1962. Moorer's conviction was

affirmed on appeal, State v. Moorer, 241 S.C. 487, 129 S.E.2d

330 (1963), and subsequently South Carolina's highest court

upheld the denial of a writ of habeas corpus to him by the state

court to which his petition had been addressed. Moorer v. State,

244 S.C. 102, 135 S.E.2d 713, cert, denied, 379 U.S. 860 (1964).

Although it alleged several nonfrivolous deprivations of

his constitutional rights, Moorer's habeas corpus petition was

dismissed without either an evidential hearing or a consideration

of the record and transcripts of the state court proceedings. In

so doing, we think the district judge was in error.

It appears to us from the record that on .all the constitutional

claims he has asserted, the petitioner has exhausted his available

state remedies, and that consideration and review of them by a

federal tribunal is now •appjepriat®. Despite the fact that this

petitioner has made several journeys through the South Carolina

judicial system and presumably has had a full and fair day in

court on each occasion, we emphasize that in situations like the

present one, it is the responsibility of the federal courts to

make the final resolution of federal. g?r>PwltUtlgnaj lfiflUfiS.*

-2-

2.3

State courts, no less than federal courts, have a duty to respect

and diligently give effect to the safeguards of personal liberty

written into the United States Constitution; but where a citizen

charges that his fundamental rights have been infringed, the federal

courts have an obligation to review independently the state court

proceedings to determine whether the findings of fact are fairly

-suggested by evidence of record and the conclusions of law are

correct. Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963).

The judgment of the court below dismissing the habeas corpus

application is vacated, and the case is remanded in order that the

district court may hold a plenary hearing in due course on factual

issues raised in the petition and undertake an independent review

of the state court legal conclusions on Constitutional points.

The district court will of course desire to enter an order staying

Moorer's execution until all issues pertaining to the abridgment

of his Constitutional rights have been finally resolved.

Vacated and remanded with instructions.

-3-

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

COLUMBIA DIVISION '

CIVIL ACTION NOy AC-1583

LOUIS MQORERijl

Petitioner/

)

vs. )

)

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and ELLIS Cjjj )

. MacDOUGALL/j Director’/ South Carolina )

State Board of Corrections, )

)

Respondents. )

f i l e d

JUt. 6

HELIN BAEEUUND

: v...

O R D E R

In accordance with the PER CURIAM decision of the

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, vacating the decision of

this Court, and directing that "a plenary hearing" be held

“on factual issues raised in the petition" and that

"independent review of the state court legal conclusions on

Constitutional points" be had,

IT IS ORDERED, upon this direction, and pursuant

to the authority given this Court under Title 28 U.S.C. § 2251,

that the execution of the sentence of death imposed by the Court

of General Sessions of Dorchester County, South Carolina^ be,

and the same is hereby stayed pending the termination of further

consideration by this Court, or the further Order of this Court.

.AND IT IS SO ORDERED;.1

Columbia/ South Carolina

July 6/1965.

ROBERT WJij HEMPHILL

United States District Judge

A TRUE COPY, ATTES't.

or n.». Disnuo* oovrw

w.Afi* 0T8T. 04EOU10

25

f

»

Xar x b s d is tr i ct c o o e t o f Fas o r x s o s ta t e s

*0* SHE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOCHI O W W

CaZXMBIA DIVISION

Civil. ACTIOS NO. AC-1383 f i l e d

£00X8 HOOKER,

Petitioner, )

)

)

>

AUG 4 1965

-HELEN BREELAND

cd .c.u.s,e.d.&c.

>

j gM^TRIAL ORDER

STATS OF scans CAROLINA and ELLIS C. )

KacEOUGALL, Director. South Carolina )

State Board of Correction*, )>

)

)Respondent*.

F o m e n t to and in accordance with the direction in

the opinion of the United state* Circuit Court of Appeal* for

the Fourth United State# Circuit, dated dun* 23, 1965, thi* Court

proceed* to determine from a rehearing and « reconsideration of the

record and the transcript*, the various issues raised in the —

petition of Hay 12, 1963, in the above styled matter. Hoorer

having charged that his constitutional rights have bean infringed,

this Court ha* an obligation to review independently the State

Court proceedings to determine whether the findings of fact are

fairly supported by evidence of record and the conclusions of lav

ar* correct, a* discussed in Townsend v. Sain. 372 0.8. 293 (1963).

States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina,

Columbia Division, on July 14, 1963. Counsel were asked if there

was any objection to the exclusion of the press, if the press

appeared, and counsel assured the Court that nor* progress at pre

trial could be expected in the absence of the press. Fortunately,

the problem did not arise.

Pre-trial conference was had in Chambers of the united

26

r; Paragraph five of the amended petition alleges violation

of the du* process and equal protection c U n u t , Noorer claiming

W o indictment by Grand Jury and his ooavictioe^, by in

«hich mesfeers of the Begro xoeo, of n M d t ho is a member, m o o

systematically and arbitrarily excluded or limited in number.

Shis issue w h s presented to tho South Carolina Supreme Court aftor

being presented to South Carolina Circuit dodge Grlafeall in a

corpus proceeding twhich subsequently was given a rehearing by

Jttdge GrimballJ but was not presented at the original trial.

Petitioner, in this Court, seeks to base his prayer for relief upon

statistical calculations, which do not appear appropo to thia

particular case. The Court presently is of tho opinion that there

was sufficient evidence developed and aired to sake a determination

in accordance with the mandate of Townsend v. Sain. supra. Counsel

for petitioner will be afforded an opportunity to argue the alleged

inadequacy of this evidence, if he feels so advised, to protect

petitioner's rights.

Paragraph six of the petition e— yTwlps of tho arraignment

of defendant in tho absence of counsel, it appears from the record

of trial that defendant was rearraigned in tho presence of counsel

and it further appears that in the habeas corpus basing before

South Carolina Fifth Circuit Judge John Grlstball that witnesses

were heard and that a full evidentiary hearing was had on this

issue. Zt searns patent that no further evidence is necessary for

a constitutional consideration of this issue. Accordingly, no

evidence thereabout will be necessary in the hearing before »*»«e

Court. Petitioner will, of course, have the right to present

argument to the Court as to why more evidence is necessary, if

he is so advised.

- a -

27

Paragraph saves alleges that ^petitioner was not given

an accurate, unequivocal and complete record of proceedings

in the Court of General Sessions . . . preceding this conviction

and sentence of death." Counsel for petitioner has «r.n/-yi1r* that

there is no need for an evidentiary hearing on this issue.

Accordingly, there will be none.

She thurst of paragraph eight was that the Sheriff had

that petitioner had made a "statement” or "confession"

at a preliminary hearing. Share was no request for an evidentiary

hearing on this issue; determination can be made from the record.

Paragraph nine alleges that petitioner was never given a

true copy of the whole indictment against him as required by j 17-408,

8. C. Code, 1862. There was and is no question but that petitioner

was not given a copy of the indictment at the time of his arraign

ment. Counsel will have the opportunity to argue the legal impact

of this denial.

She issue raised in paragraph tea, which alleges that

S 16-71, 8. C. Code, 1962, (the statute which defines rape), is

upon its face and as construed and applied to petitioner, vague,

indefinite and uncertain. Counsel agreed that no evidentiary

hearing is necessary thereabout and that the matter would be

presented to the Court by way of legal argument.,

As to paragraph eleven of the May 12 petition, counsel

agreed at the hearing that no evidentiary hearing was necessary

but that the sufficiency of the evidence to sustain the conviction

would be fully explored by counsel in legal argument at the bearing

hereinafter discussed. Counsel are free to make reference to any

and all transcripts and shall be prepared to cite to the Court

relevant portions and pages thereof.

•* 3 «*

28

Counsel agreed that the natters set forth in paragraph

tveive of the petition were first raised is this petition. MO

evidentiary hearing was requested, after discussion, and the issue

to be discussed and argued before the Court is whether or not the

alleged confession was voluntary, which includes the question of

whether the jury should have been excused during the m s e ssion,

thereabout in the Court of General Sessions for Dorchester County

on trial of the cause.

Paragraph thirteen alleges that f 16-72, S. C. Code, 1962,

(which prescribes the death penalty for conviction of rape) upon

its face and applied to petitioner under the drcuastanoee here

violates the fourteenth Amendment in that*

a) it imposes a cruel and unusual punishment* and

b) there has been unequal application of this

statute and a long standing practice, policy, and

custom of “sentencing Negro men to death for rape

upon white women while not inflicting this punish

ment upon any other person."

fart “a" clearly presents a natter of law for the Court and counsel

agreed that no evidentiary hearing was necessary or warranted.

As to subparagraph “b*, this Court must determine, and

counsel are directed to advise, as to (1) the constitutional

dimunition claimed; (2) the basis or competency of any statistical

evidence sought to be introduced; (3) whether the parties can

stipulate satisfactorily to the end that the Court can rule on

this contention as a matter of law; and (4) whether the "logical

extreme* of the "evidence" possible in this case will have a

salutory effect on the proper administration of justice. Of

course, the question of unconstitutional application, if such

exists, of the statute with reference to RAPE may be fully argued

in this hearing.

nothing herein shall limit the right of petitioner to .

present fall argument on any of the issues, or to •eke a notion

that the plenary hearing hereinafter directed be snore ■exhaustive"

SJ.?

than the foregoing euggeats.

Counsel agreed that it would not be necessary for petitioner

to be present at the bearing, that hie absence therefrom would in

no wise deny him any constitutional right as neither counsel nor

the Court find it necessary to take his testimony on eny issue

considered*

Counsel will confer in advance of hearing to ascertain

if stipulations can be agreed upon and will advise the Court

thereabout in the briefs mentioned below*

A plenary hearing will be held la the courtroom of the

United States District Court at Columbia, South Carolina, at

10*00 A. K., August 18, 1965, and continue thereafter until

consansaated* five days in advance of said bearing, counsel trill

present the Court with a brief expressing fully upon the legal

and factual issues set by this Order and by agreement, and shall

present agreed stipulations. In said brief shall be noted all

appearances expected at the hearing and a statement as to the

approximate time desired for presentation and argument.

Other hearings will be had upon justification shown.

a d d It IS SO ORDERED.

ROBERT W. -iiEMFEXIiI<

~ ~ ROBERT W . BEMJPHHJ,...................

United states District judge

ColumbiSf South Carolina

A TRUE CUPi. m 'ibbi.

or O. 8. niSTBIOT ĈTTST

29

\

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

COLUMBIA DIVISION

LOUIS MQOREft,

j Petitioner,

-v*-

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA and ELLIS C. tecDOUGALL, Director, South Carolina State Board of Correction*,

Respondent*.

MOTION

Petitioner, Loui* Atoorer, by hi* attorney*, respectfully

moves the Court for leave to withdraw Petitioner** Exhibit 1 for

the purpose of making photostatic copies thereof.

At the hearing on the amended petition for writ of habeas

corpus held on August IS, 1965, petitioner presented a cardboard

carton containing 355 forms, or schedules, entitled •Capital

Punishment Survey,* each schedule consisting of 28 printed pages

and containing information gathered by researchers on cases re

sulting in conviction of rape in several South Carolina counties.

The Court ordered that the carton be sealed and marked Petitioner's

Exhibit 1, with permission to withdraw the exhibit or make photo

static copies to be granted only upon submission of a motion show

ing good cause.

Petitioner requires the schedules comprising Petitioner's

If

)

}

)

) CIVIL ACTION No.

)

)

)

30

i f

Exhibit Mo. 1, or a photoatatic copy thereof, to that’scientific

analysis and computation can ba conducted on the basis of the in

formation contained in the schedules. Such analysis and computa

tion are necessary for purposes of scientific research and for

further use of the materials in this litigation.

The gathering of data contained in Exhibit No. 1 was conduct

ed at great expense,over a period of savaral months,and with

considerable care end preparation. Petitioner does not have a

copy of the schedules comprising Exhibit No. 1. The gathering of

data had not been completed in time for duplication of the sched

ules by August 18, 1965.

if this motion is granted, counsel for petitioner will

supervise the process of duplication, insure that the exhibit

is in no way altered, and promptly return the exhibit to the Court.

Petitioner will pay the cost of copying the materials.

jMTHE# y. PEAKY y

lljO?̂ Washington Street Columbia, South Carolina

F. HENDERSON MOORE 39 Spring Street Charleston, South Carolina

BENJAMIN t. COOK, JR.42 Morris Street

Charleston, South Carolina

JACK GREENBERG FRANK HcFFAON

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

2

I-

ts THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE SUITED STATES

FQK THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH C&SOIdHS

COLUKB2A DIVXSXOS

CtVXD ACTIOS HO. AC-1583 V

LOUIS MOOSES,

' \ %

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF SOUTH ORHQLISA and ELLIS C.

KacDOUG&LL, D irector, South Carolina

S tate Board of C orrection s,

Respondents.

Before the United States D is t r ic t Court f o r th e D is t r ic t o f South

Carolina, a t Columbia, South C arolina. Robert W. Hemphill

D is t r ic t Judge.

Heard August 13, 1965 Decided January 3, 1966

Matthew J . Perry, Esquire, Columbia, S . C ., and Frank H. Hefrron,

iisquire, o f Hew York C ity , fo r p e t it io n e r . Honorable Daniel R,

McLeod, Attorney General o f South C arolina, Columbia, S. C .,

Edward B. Latimer, Esquire, A ssistant Attorney General, Columbia,

S. C ., E. H. Brandon, Esquire, A ssistant Attorney General, Columbia,.

S. C ., and Julian S . N olle , S o l ic it o r , F irs t C ir cu it , Orangeburg,

32

Pursuant to d ir e c t io n of tb s United States Court of Appeals

fox the fourth Judicial C ir c u it 1 this Court undertook further proceed

ings herein. This2 p resen ts to this Court again questions which have

been previously d ecid ed o r new q u e stio n s obviously pursued for delay.

As noted by United S ta tes C ir c u it Judge3 Jean S. Breitenatein in a

recent presentation t o a Seminar o f United States Judges at Denver.

Colorado*

A fte r in ca rce ra t io n th e p r iso n e r s t a r t s t o b rood

o v e r every th in g th a t has happened between a r re s t and

sen ten ce . B is d is s a t i s fa c t i o n i s encouraged by th e

ja i l -h o u s e law yers who are t o be found in c o s t penal

in s t i t u t io n s . Soon he i s bombarding th e ju dge w ith

req u ests f o r r e l i e f which range from o b je c t io n s on

th e s e v e r ity o f the sentence t o cla im s th a t th e

p roceed in gs are i l l e g a l f o r v io la t io n o f b a s ic

c o n s t itu t io n a l r ig h t s .

In tlie p a st f i f t e e n years th e a p p lica t io n s t o th e

fe d e r a l c o u r ts f o r p o s t c o n v ic t io n r e l i e f have s te a d ily

in cre a se d . Perhaps t h is r e s u lt s from an in cre a s in g

awareness o f , and emphasis on , the c i v i l r ig h ts o f the

in d iv id u a l . C e rta in ly th e d e c is io n s o f th e Supreme

Court ind icate- a growing concern over the c o n s t itu t io n a l

r ig h t s o f accused person s and th is con cern has mani

fe s te d i t s e l f in more com prehensive treatm ent o f con

s t i t u t io n a l p r o v is io n s designed t o p r o t e c t such p erson s .

The amended p e t i t i o n 4 seeking r e l i e f h ere in was f i l e d May 12,

1355, and reads as fo llo w s*

The amended p e t i t i o n o f L ou is Moorer r e s p e c t fu l ly

shows t o t l i is H onorable Court*

1.

P e t it io n e r i s now u n law fu lly re s tra in e d o f h is

l ib e r t y a t p resen t in cu stod y o f E l l i s C . K acD ougall,

D ire c to r o f th e South C aro lin a S ta te Board o f

C o rre ctio n s a t th e South C aro lin a S ta te P e n ite n tia ry

a t 1515 G ist S tr e e t , Columbia, South C a ro lin a , in

v io la t io n o f the C o n stitu tio n o f the United S ta tes o f

Am erica, aw aiting the i n f l i c t i o n o f death sen ten ce by

e le c t r o c u t io n a ga in st h is w i l l f o r th e a lle g e d crim e

o f ra p e .

1 See P oorer v. Str. to o f Couth C a ro lin a , c t a l . 347 F .2d 502.

2 see Moorer v . State o f South Car o l in a , c t a l , 239 F.Supp. ISO*

Moorer v . S ta te o f Couth C a ro lin a , e-t a l , 240 F.Supp. 529; and

p o o re r v . S ta te o f Couth Car o l in a , efc a l , 240 F.Supp. 531 (th e

la s t o f which chronologuea th e h is to r y o f t h is p o s t -c o n v ic t io n

d e la y p a t te r n ) .

3 Tenth C ir c u it . 33

4 F ile d Hay 12, 1955.

2.

The fa c t s in co n n ection w ith th e a fo r e s a id

d e te n tio n and pending i n f l i c t i o n o f th e death,

sen ten ce w i l l he p resen ted to t h i s C ou rt, in

c lu d in g p roceed in gs o r ig in a t in g , ou t o f th e Court

o f G eneral S ess ion s f o r D orch ester Comity in th e

S ta te o f South C a ro lin a , th e Court o f Common Flc-as

f o r R ichland County, South C a ro lin a and a l l p roceed

in g s b e fo r e th e Supreme C ourt o f th e S ta te o f South

C aro lin a and i t s d e c is io n s th ereon ,

3. /

• /

Upon th e t id a l o f p e t it io n e r in s a id C ourt o f

G eneral S e ss io n s f o r D orch ester County, S ta te o f

South C a ro lin a , p e t i t io n e r was co n v ic te d o f th e

crim e o f rape which judgment o f c o n v ic t io n was,

upon appeal t o th e Su.prer.ie Court o f th e S ta te o f

South C a ro lin a , a ff ir m e d . ' S ta te v . lo r d s P oorer ,

129 S .E .(2d) 330 . T h e re a fte r , a p e t i t i o n was f i l e d

•in th e Court o f Coarsen f le a s f o r R ichland County,

South C aro lin a f o r a W rit o f Habeas Corpus which

p e t i t i o n was d e n ie d . The Supreme Court o f South

C aro lin a a ffirm ed th e Order denying th e P e t it io n

f o r W rit o f Habeas C orpus, f o u ls P oorer v . S tate

o f South f c o h i u . c t n T .. 135 S .E .(2d) 713. There

a f t e r , a p e t i t i o n was f i l e d in th e Supreme Court of

th e U nited s ta t e s f o r a W rit o f C e r t io r a r i which

p e t i t i o n was denied O ctober 12, 1964. G.S . .

13 L.Ed. 2d 63 .

4 .

P e t it io n e r com plained and com plains th a t he was

n o t accorded a f a i r t r i a l and begs lea ve t o submit

upon th e hearing h ere in th e re co rd s in th e cou rse

o f th e p roceed in gs h e r e to fo r e had in con n ection

w ith th e ind ictm en t and c o n v ic t io n and th e appeals

th erefrom wherein and wherefrom t h is Court may be

a p p rised o f th e co n te n tio n s o f p e t it io n e r and

p e t i t io n e r p reys th a t such re co rd s b e deemed t o have

been made a p a r t o f t h is p e t i t i o n b y r e fe r e n c e .

P e t it io n e r fu r th e r d e s ir e s t o p resen t a d d it io n a l

ev iden ce in support o f M s co n te n tio n th a t h is

c o n v ic t io n in th e S ta te C ourt v io la te d th e C on stitu

t io n o f th e U nited S ta te s .

5 .

P e t i t io n e r 's r e s t r a in t and d e te n tio n v i o la t e th e

due p rocess and eq u a l p r o t e c t io n c la u s e s o f th e

Fourteenth fctaondffient t o the C o n stitu tio n o f th e

United S ta tes in th a t he was in d ic te d by a grand

ju ry and co n v ic te d by a p e t i t ju r y from which

members o f th e negro ra ce , o f which p e t it io n e r i s

a member, were sy s te m a tica lly and a r b i t r a r i ly ex

clu ded o r l im ite d in cumber*

a ) Hegroes c o n s t itu te in e x ce ss o f 40 p er

c e n t o f th e a d u lt p op u la tion o f D orchester

County. 34

2 -

b) Hegroes c o n s t it u t e in excess of 20 per

ce n t o f th e r e g is te r e d voter® l a South

C a ro lin a .

c ) n egroes c o n s t itu te d o n ly 6.755 o f th e

p erson s on grand ju r ie s in Dorchester

County between 1953 and 1962.

dj On 4 of th e 9 p e t i t ju r y venires drawn in

D orch ester County between 1958 and 1962,

so K egrocs w ere on th e p e t i t jury venire.

e ) On th e 9 p e t i t ju r y v e n ire s drawn in

D orch ester County between 1953 and

1962, o n ly 2.155 o f th e p erson s drawn

w ere K cgroes, and no box® than 2

D egrees were p la ce d on any p e t i t ju r y

v e n ir e .

£ ) Between 1943 and 1932, no Segxoes

a c t u a lly sa t cn p e t i t ju r ie s in Dor

c h e s te r County.

g) *Ehe token masher o f H egroes p la ce d on

petit jury v e n ire s are c o n s is t e n t ly

challenged o r stricken, so that Scgroea

a re prevented fresa s e r v ic e on petit

ju r ie s .

h ) A i l ju r y con ssisa loaers in D orch ester

County a re w h ite .

1 ) P ro sp e c tiv e ju r o r s a re chosen from

voting registration lists which d esig n a te

th e race of each voter.

S.

P e t i t io n e r ’ s restraint and d e te n tio n v io la t e s th e due

p ro ce ss clause of th e Fourteenth Arsentteenfc t o th e

C o n stitu tio n of th e United States in th a t he was taken

in t o C ourt, a t the conmcr.cosicat o f th e te n s o f Court

in w hich ho was tried, and was subjected t o an a rra ig n *

sent proceeding on April 2, IS62 w ith ou t an A ttorney

and was n ot advised by th e Court nor b y any o th e r

o f f i c i a l o f the right to be- represented by an a tto rn e y

during s a id arraignment proceeding o r o f th e r ig h t t o

co n s u lt w ith an attorney prior th e re to .. She arraignm ent

o f A p r il 2 , 1932 was a critical stage o f th e p roceed in gs

in th a t i t was a prerequisite t o th e v a l i d i t y o f a w a iver

o f defendant*a rights under faction 17-4-38, Coda o f lew s

o f South Carolina for 1962,. which a llo w s a defendant t o

have a cop y o f the indictment f o r th re e days b e fo r e b e in g

brou gh t t o t r i a l . Petitioner was t r ie d on A p r il 4 , ISS2,

o v e r o b je c t io n o f co u n se l, l o s s than th ro e days a f t e r being

p resen ted w ith a copy o f th e ia d lc t a e a t « She H onorable

John c r install. Judge o f th e Fifth J u d ic ia l C ir c u it , who

den ied petitioner’s petition f o r habeas corpus,, e rre d in

f in d in g th a t petitioner tea co u n se l a t his arraignm ent

o f A p r il 2 , 1552.. 35

Petitioner's restraint and detention violate*

the Podrtdentli .feSnaiteiife ̂tS tfee Waited States

Constitution in .t t ia t p e t i t io n e r was not given an

accurate, traebuivSeal arid msfjiete rmooid of all

proceedings in the Court .of G eneral Sessions for

Eorchoster County preceding tfids conviction and

sentence of death.

a.

P e t i t i o n e r 's r e s t r a in t and d e te n tio n v i o l a t e !

th e due p ro ce ss c la u se o f th e Fourteenth amendment

t o th e C o n st itu t io n o f th e United S ta te s in th a t

h e was su b je c te d t o a p re lim in ary h earin g o r boss®

o th e r p r e - t r i a l proceeding w ith ou t an a ttorn ey and

w ith ou t b e in g adv ised off th e rjtghfc ttf have ait..,,

a tto rn e y p resen t o r o f th e r ig h t Jgfinsujt w ith an

a tto rn e y p r io r t o th e ccsasenceaiisrlfe ■&£ s a id $±88§$i!iM§

9.

P e t i t i o n e r 's r e s tr a in in g and d e te n tio n v io la t e s

th e duo p ro c e s s d a n c e o f th e Fourteenth Miettfb-fertt

t o tli© C o n stitu tio n o£ th e United s ta t e s in that he

was t r ie d and co n v ic te d o f n c a p it a l o f fe n s e ; t o

w it* ra p e , and was a t no i r r ib . boj>y, b£

th e w hole in d i c t .v i t s g i i r ^ t him 1 5 i s req u ired bySection 17-4CQ, cdai 8'i b£ s8liS cafaiini fEt1962.

10.

P e t i t i o n e r 's r e s t r a in t and d e te n tio n <b io ia t| S j th e

due p ro ce ss c la u s e o f th e F o u r te e n ^ J a ^ ^ § j| iL fcS

th e C o n st itu t io n o f the United StatSiS. iri,|fiS| l i f ¥ l i

t r i e d , c o n v ic te d and sentenced tb < e a t» £ d f having

a l le g e d ly v io la te d S e c tio n 15-71 , Coda Of haws.Of

South C aro lin a f o r 1962 w hich c ta tu te ip upon i t s

fa c e end as con stru ed and a p p lie d fb p E titib r ib t;

vague; iH d b fin itS fend M a s fft i i i i ;

f 1i t :

§SB| i8 fe ll m ,:

eSgcfitlit.iilir

thip EoSviSfeii IJiSjSufe ̂ i&SSfibu ..

.._,.8f ei§ SffeSj iaS il ilmSlii?MS IIS Ivi&glteS of fltiiSsiMtsSii:

1 0 12:

. P e t it io n e r tun® d e p r iv e d Off bus p ro ce ss o f law .and

th e equal p r o te c t io n o f the le.ro in v io la t io n o f the

Fourteenth do.'oo d t o th o United S ta tes C o n stitu tio n

in th a t th e t S I a l c o u r t .S s f& ^ I^ w ifr ib g sis tb

t e s t i f y in thS prbSsnbb 8 f tlie ju ry th a t h bbtriiitsr^

statem ent had fceea taken from th e defendant

soon a f t e r h is a r r e s t . T h is testim ony was-

h ig h ly p r e ju d ic ia l t o d efen dan t s in ce i t

s t r o n g ly suggested th a t defendant had v o lu n ta r ily

co n fe s se d , and t e e Issu e s o f a d m is s ib i l i t y o f a

c o n fe s s io n m ist ba d ecid ed b e fo r e t r i a l b y th e

co u r t and. o u t o f th e p resen ce o f th e ju r y .

13.

P e t it io n e r ’ s- sentence of death was imposed

pursuant to Section 1 6 -72 , Code o f law s o f South

C aro lin a f o r 1062, which statute i s upon i t s fa c e

and as applied to petitioner under th e circu m stan ces

o f t l i i s ca s e , in violation of the Fourteenth amend

ment t o th e Constitution of the B aited S ta te s , in

th at*

a ) Said statute authorizes im p o s itio n o f a

cruel, inhuman and unusual punishment in

violation ox the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments t o th e C o n st itu t io n o f th e

United States.

b ) Said s ta tu te denies p e t i t io n e r equal

protection of the law and due p ro ce ss o f

law under the Fourteenth Amendment t o th e

Constitution of the United S ta te s in th a t

there has been an unequal a p p lic a t io n o f

sa id statute and in that th e re i s and has

been a long standing p r a c t i c e , p o l i c y and

custom of sentencing ilegro men t o death f o r

rap© upon which women while n ot i n f l i c t i n g

th a t punishment upon any o th e r p erson .

14.

Hie constitutional claim raised in Paragraph 9 above was

ra ise d a t petitioner's trial and passed upon a d v e rse ly t o

p e t i t io n e r by tea supremo Court o f South C a ro lin a , a ff ir m

in g th e conviction. Ct-.ta v. i-sorer. 241 S .C . 467, 129

S. E. (2d) 330 (1963). 2ho c o n s t it u t io n a l cla im s made in

Paragraph 5, 6, 7 end 8 ware raised on p e t i t i o n e r ’ s p e t it io n

f o r habeas corpus in the Fifth J u d ic ia l C ir c u it o f South

C aro lin a and decided adversely t o p e t i t io n e r by th a t Court

and b y th e Supreme Court o f Couth C arolin a a ff in n in g th e

d e n ia l o f habeas corpus, bgcrer v . s t a t e . s.c ._____ ,

135 S.E.(2i) 713 {1904). *„ie rem aining c o n s t itu t io n a l

claims heroin set forth were d ecid ed a d v e rse ly t o p e t i t io n e r

in an Order o f th e Couth Carolina Supreme C ourt dated Kay I I ,

1355.

15.

S o p re v io u s a p p lic a t io n f o r th a r e l i e f sought h erein bas

been made t o t i l l s Court c r any ju d ge th e r e o f .

KBESBFOE2, petitioner prays t e a t a W rit o f Habeas Corpus,

d ir e c te d t o Ellis C. K acE ougall, b i r e c t o r o f South C aro lin a

37

5

S ta te Board o f C o rr e c t io n s , b y wham p e t i t i o n e r i s

d eta in ed and by whom e x e cu tio n o f p e t i t i o n e r 's

sen ten ce o f death i s ord ered t o be ca r r ie d o u t ,

is s u e f o r th e purpose o f in q u ir in g into the cause

o f s a id im prisonm ent and re s tra in t , and of d e liv e r in g

him therefrom pursuant t o th e s ta t u t e in such ca se s

saade and p ro v id e d .

On May 12, 1SS5, t h i s C ourt issu e d i t s Order*

By p e t i t i o n o f Kay 11, 1SS5, p e t i t i o n e r seeks

s ta y o f e x e cu tio n and fu r th e r d e la y o f th e p ro ce sse s

o f th e C ourts o f o r ig in a l and a p p e lla te ju r is d i c t io n s ,

t o w it , th e C ourts o f th e sov ere ig n S ta te o f South

C a ro lin a . P rev iou s o rd e rs o f t h is C ourt d e t a i l n ot

o n ly th e in d u lgen ce o f t h i s C ourt t o p e t i t io n e r upon

M s. p le a o f r ig h t t o a d ju d ic a t io n o f th e v a r io u s issue®

p u rp o rte d ly p re d ica te d upon a d e n ia l o f th e r ig h t s o f

p e t i t io n e r in co n n e ctio n w ith h is t r i a l , judgment and

sen ten ce f o r th e crim e o f B spe.

The Supreme C ourt o f South C a ro lin a , having under

i t s a u th o r ity th e e x e cu tio n o f p e t i t io n e r , and having

heard, on Hay IB, 1955, a m otion f o r s ta y o f ex ecu tion

ponding the a p p lic a t io n o f p e t i t io n e r f o r a W rit o f

Habeas Corpus t o th e Court o f Common P lea 3 , R ichland

County, South C a ro lin a , upon grounds con s id ered and

rep orted in th e subsequent o rd e r o f South C a r o lin a 's

h ig h e s t Court e s o f Kay 11, 1553, ru led

"A fte r a c a r e fu l c o n s id e r a t io n o f a l l o f

th e co n te n tio n s o f th e d efen dan t, th e n o t io n

i s hereby d e n ie d .*

T h is Court f in d s n oth in g b e fo r e i t a t t h is tim e

upon w hich any determ in ation o f t h i s C ourt co u ld be

had to t lie effect th a t p e t i t i o n e r has n ot had h is day

in C ou rt, o r th a t th e v a riou s is s u e s p resen ted have

n ot been con s id ered by a C ourt o f a ccep ted and recogn ized

ju r is d i c t io n t o hear and determ ine each and every o f such

is s u e s .

In stead o f a d e n ia l o f due p r o c e s s , t h is Court f in d s

a p a tte rn o f design ed d e la y . la a re ce n t o rd e r o f t h is

C ourt, va ca tin g t h is C o u r t 's p re v io u s s ta y o f ex e cu tio n ,

d is c u s s io n and r e c i t a t i o n was had o f th e v a riou s

o p p o r tu n it ie s and p r iv i le g e s o f appearance and p resen ta

t io n w hich p e t i t io n e r has had. The South C aro lin a Courts

having g iven th e p e t i t io n e r a h earing and f u l l co n s id e ra

t io n , t h is Court finds n e ith e r p ro p r ie ty nor ju s t i f i c a t i o n

in in je c t in g o r p r o je c t in g th e ju r is d i c t io n o f t h i s Court

fu r th e r in t o th e m a tter. T h is Court was n e ith e r cre a te d ,

nor d esign ed , to sit in a p p e lla te judgment on S ta te Court

a c t io n s , nor have d e c is io n s p re v io u s ly r e fe r r e d t o , and

p o p u la r ly accla im ed , changed e it h e r th e co n fin e s o f t h i s

C o u r t 's ju r is d i c t io n o r th e n e c e s s ity th a t t h is C ourt,

w ith in th e l im ite d d u t ie s and r e s p o n s ib i l i t i e s , d es ign a ted ,

seek t o p re d ic a te a f i n a l i t y in o rd er th a t th e w hole o f

th e p e o p le as a s o c ie t y m ight have ju s t i c e dona in b e h a lf

o f th a t s o c ie t y .

6 -

A sid e from th e tremendous (d a re we say a t tim es

u n ju s t i f ie d ) expense in v o lv e d in th e numerous

h earin gs upon th e va riou s p e t i t i o n s , whether d e c la re d

f r iv o lo u s o r n o t , th e re i s th e r e c o g n it io n th a t the

h ig h e st c o u r t o f th e lan d , th e Supreme C ourt o f th e

United s t a t e s , re fu se d c e r t i o r a r i on p rev iou s m atters

now sought t o he again en te rta in e d b e fo r e t h i s C ourtf

t h i s C ourt cannot and w i l l n o t , u n less d ir e c te d by

h ig h er a u th o r ity , go beyond th e c ircu m s cr ip t io n o f

d ir e c t io n o r in d ir e c t io n o f th a t h ig h e st co u r t h e re to

f o r e rendered in con n ection w ith th e cla im s o f p e t i t i o n e r .

t h i s Court f in d s no b a s is f o r fu r th e r ju r is d i c t io n ,

th e re b e in g no determ in ation by t i l l s Court th a t the

C o n s t itu t io n a l E ights o f th e p e t i t io n e r have been

d en ied , o r d eprived him, b y , o r in , th e C ourts t o which

he has re s o r te d , o r which have a sse rte d ju r is d i c t io n o r

d e c is io n p r e v io u s ly , th e Amended P e t it io n f o r W rit o f

Habeas Corpus i s re fu sed because o f in s u f f i c ie n c y th e r e o f

as ex p la in e d .

Further s ta y o f ex ecu tion by t h is Court i s d en ied .

Further ju r is d i c t io n o f t h i s Court i s d iv e s te d .

ASD IX IS SO OSDEEE0.

On Kay 13, 1965 th e C h ie f Judge o f th e U nited S ta te s Fourth

C ir c u it C ourt o f Appeals o rd e re d »

th e a p p e lla n t has a p p lied t o mo f o r a s ta y o f

e x e cu tio n o f a sen ten ce o f death now scheduled t o

b e executed tomorrow, bay 14, 1965.

The a p p e lla n t has f i l e d a p rop er n o t ic e o f appeal

from an ord er en tered in th e United S ta tes D is t r i c t

Court f o r th e Eastern D is t r i c t o f South C arolin a on

Kay 12, 1955, denying an amended p e t i t i o n f o r habeas

co rp u s . Hie m otion f o r stay i s f o r th e purpose o f

p r o te c t in g th e ju r is d i c t io n o f th e U nited S ta tes Court

o f Appeals durin g the pendency o f th e ap p ea l.

The record on appeal d is c lo s e s se v e ra l p roceed in gs

in th e s ta te c o u r ts , in which th e re a re a number o f

a sserted cla im s o f d e n ia l o f r ig h ts p ro te c te d by th e

C o n stitu tio n o f th e United S ta te s . The amended p e t i t i o n

f o r habeas corpus in th e D is t r i c t C ourt and th e e a r l i e r

p e t i t i o n in th a t Court sought r e l i e f upon th ose grounds.

I t fu r th e r appears th a t th e D is t r i c t Court has not con

s id e re d th e c o n s t itu t io n a l c la im s upon t h e ir m e r its .

There has b e ta no e v id e n tia ry hearing in th e D is t r i c t

Court and, co fa r as now appears in th e record on appeal,

no rev iew in th e D is t r i c t Court o f th e s ta te co u r t p ro

ceed in g s to co n s id e r whether o r n o t in th e s ta te p roceed in gs

th e fe d e r a l cla im s have been f a i r l y heard and determ ined.

On t h e ir fa c e , I cannot say th a t the fe d e r a l c o n s t it u t io n a l

cla im s are f r iv o lo u s o r th a t th e appeal i s n ot w ithout

p rob a b le m e r it . Indeed, the D is t r i c t Judge c e r t i f i e d ,

f o r the purpose o f p r o te c t in g th e r ig h ts o f th e a p p e lla n t,

tlie e x is te n ce o f p rob ab le cause to app ea l.

- 7 -

l a th e se circu m stan ces , e x e cu tio n o f th e sen ten ce

would e f f e c t i v e l y deny th e r ig h t o f a p p ea l, and a

s ta y o f th e e x e cu tio n i s e s s e n t ia l f o r th e p r o te c t io n

o f th e ju r is d i c t io n o f th e U nited S ta te s Court o f

a p p ea ls t o hear end determ ine th e a p p e lla n t ’ s r ig h ts

in th e p r e c is e s .

There i s a ls o b e fo r e tee a p e t i t i o n o f th e a p p e lla n t

f o r le a v e t o p roceed in forraa p a u p e r is . For th e reason s

s ta te d above, X have determ ined t o gran t th e p e t i t i o n

f o r le a v e t o p roceed w ith ou t prepayment o f f e e s , t o

c e r t i f y th e e x is te n ce o f p rob a b le cau se t o ap p ea l, and

t o o rd e r a s ta y o f th e e x e cu tio n pending th e d eterm in ation

o f th e appeal in th e U nited S ta te s C ourt o f A ppeals f o r

th e Fourth C ir c u i t .

IT XS ORDERED, t h e r e fo r e , th a t th e a p p e lla n t b e , and

he i s h ereby , p erm itted t o p ro se cu te h is appeal in t h is

C ourt in th e above e n t i t le d ca s e in forraa p au p eris in

accord an ce w ith T i t l e 28, t f .S .C ., § 1915, w ith ou t the

prepayment o f c o s t s o r th e g iv in g o f s e c u r ity th e r e fo r .

Fosrnsa ORDERED th a t th e C lerk o f t h i s C ourt f i l e th e

p re lim in ary re c o rd on appeal and d o ck e t th e appeal a s o f

Kay 13, 1SSS.

FURTHER ORDERED, upon co n s id e r a t io n o f th e p e t i t i o n

and pursuant t o th e authority under T i t l e 28, 0 .3 .C .,

§ 2251, th a t tiis e x e cu tio n of th e sen ten ce o f death

im posed by th e Court o f General S ession s o f D orch ester

County, S ta te of South Carolina, b e , and th e same i s

h ereby , stayed pending th e term in ation o f th e appeal

h ere in o r th e fu r th e r o rd e r o f th e C ou rt.

May 13, 1955

/ s / Clement F . Eayaaworth, J r .

C h ie f Judge, Fourth C ir c u it

Subsequent t o th e a p p e lla te o p in io n th e C ou rt, t o e x p e d ite

had a p r e - t r i a l co n fe re n ce which re s u lte d in an Order o f August 4 ,

1965*

Pursuant to and in accordance w ith th e direction in

the opinion of the United States C ir c u it Court o f

Appeals for the Fourth United States Circuit, dated

June 23, 1335, this Court proceeds t o determine from

a rehearing and a reconsideration o f the record and

the transcripts, the v a riou s issues raised in the

amended petition of May 12, 1935, in the above styled

matter. Moorer having charged that h is constitutional

rights have been infringed, this Court has an obligation

to review independently the State Court proceedings t o

determine whether the findings o f f a c t are fairly

supported by evidence of record and the conclusions o f

law are correct, as discussed in Townsend v. Cain,

372 0.3. 293 (1963). ” 40

s -*

Paragraph f i v e o f th e amended p e t i t i o n a l le g e s

v io la t io n o f th e due p ro ce ss and equal p r o te c t io n

c la u s e s , floo rer c la im in g h is ind ictm en t by Grand

Jury and h is c o n v ic t io n by P e t i t Jury in w hich

members o f th e S egro r a c e , o f w hich he i s a member,

were s y s te m a t ic a lly and a r b i t r a r i l y excluded o r

l im ite d in number* T h is issu® was p resen ted t o th e

South C aro lin a Supreme Court a f t e r b e in g p resen ted

t o South C a ro lin a C ir c u it Judge G rin-ball in a habeas

corpus p roceed in g {which su bsequ en tly was g iven a

reh ea rin g by Judge G rim ball) b u t was n o t p resen ted

a t th e o r ig in a l t r ia l* P e t it io n e r , in t h is C ourt,

seeks t o base h is p rayer f o r r e l i e f upon s t a t i s t i c a l

c a lc u la t io n s , which do n ot appear apropos t o th is

p a r t ic u la r c a s e . The Court p r e s e n t ly i s o f th e

o p in io n th a t th e re was s u f f i c i e n t ev id en ce developed

and a ire d t o make a determ in ation in accordan ce w ith

th e mandate o f Townsend v* Sain , su pra . Counsel f o r

p e t i t io n e r w i l l be- a ffo rd e d an op p o rtu n ity t o argue

th e a lle g e d inadequacy o f t h i s e v id e n ce , i f he f e e l s

s o a d v ised , t o p r o t e c t p e t i t i o n e r ’ s r ig h t s .

Paragraph s i x o f th e p e t i t i o n com plains o f the

arraignm ent o f defen dan t in th e absence o f c o u n s e l.

I t appears from th e re co rd o f t r i a l th a t defen dan t

was rea rra ign ed in th e p resen ce o f co u n se l end i t

fa r th e r appears th a t in th e habeas corpus h earing

b e fo r e South C aro lin a F i f t h C ir c u it Judge John c r im b a ll

th a t w itn e sse s were heard and th a t a f u l l e v id e n t ia ry

h earin g was had on t h is is s u e . I t seems p aten t th a t no

fa r th e r ev iden ce i s n ecessary fa r a c o n s t it u t io n a l

co n s id e ra t io n o f t h is i s s u e . A cco rd in g ly , no ev iden ce

th ereabou t w i l l b e n ecessary in th e h earin g b e fo r e t h is

C ou rt. P e t it io n e r w i l l , o f co u rse , have th e r ig h t t o

p re se n t argument t o -the C ourt as t o why more ev id en ce

i s n e ce ssa ry , i f he i s so a d v ise d .

Paragraph seven a l le g e s th a t "p e t it io n e r was not

g iven an a ccu ra te , u n equ ivoca l and com plete re co rd

o f a l l p roceed in gs in th e C ourt o f General S ession s

. . . p reced in g t h is c o n v ic t io n end sen ten ce o f d e a th ."

Counsel f o r p e t i t i o n e r has conceded th a t th ere i s no

need f o r an e v id e n t ia ry h earin g on t h is is s u e .

A cco rd in g ly , th ere w i l l b o none.

The th ru s t o f paragraph e ig h t was th a t th e S h e r i f f

had t e s t i f i e d th a t p e t i t io n e r had made a "statem ent"

o r "c o n fe s s io n " e t a p re lim in a ry h ea r in g . Shore was

no req u est f o r an e v id e n t ia ry h earin g on t h is is s u e ;

determ in ation can b e made from th e re c o rd .

Paragraph n in e a l le g e s th a t p e t i t io n e r was never

given a t ru e copy o f th e w hole in d ictm en t a g a in st

him as req u ired by § 17 -403 , S . C. Cocks, 19-32.

There was mid i s no q u estion bu t th a t p e t i t io n e r was

n ot g iv en a copy o f th e ind ictm en t a t th e tim e o f

h is arraignm ent. Counsel w i l l have the op p ortu n ity

t o argue th e le g a l im pact o f t h is d e n ia l . 41

is s u e ra ise d in paragraph t e a , w hich a l le g e s