Roemer v Chisom Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1988

94 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Roemer v Chisom Writ of Certiorari, 1988. c14458c3-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95ebd28f-c9ac-4740-87fc-e67db66aeda4/roemer-v-chisom-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

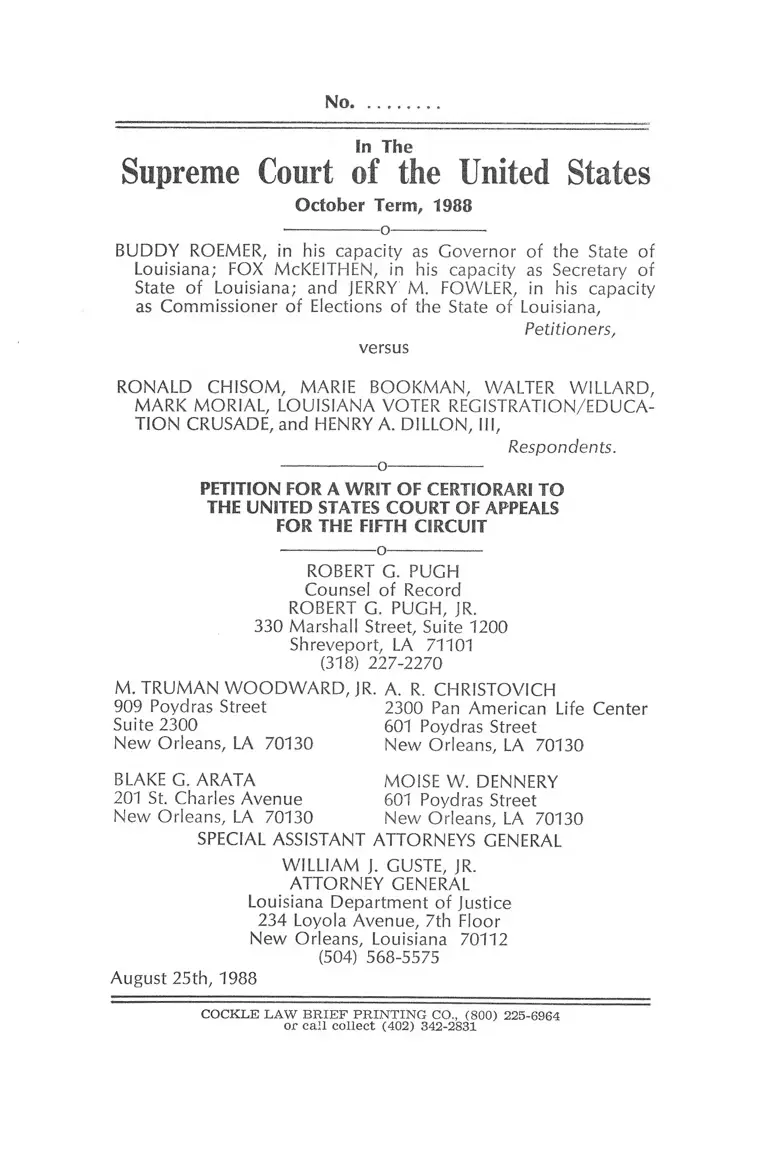

No.

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1988

-o-

BUDDY ROEMER, in his capacity as Governor of the State of

Louisiana; FOX McKEITHEN, in his capacity as Secretary of

State of Louisiana; and JERRY M. FOWLER, in his capacity

as Commissioner of Elections of the State of Louisiana,

versus

Petitioners,

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN, WALTER WILLARD,

MARK MORIAL, LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/EDUCA-

TION CRUSADE, and HENRY A. DILLON, III,

Respondents.

-------- ----- o---------- -—

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

------------- -— o----- -— ------

ROBERT G. PUGH

Counsel of Record

ROBERT G. PUGH, JR.

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

(318) 227-2270

M. TRUMAN W OODW ARD, JR. A. R. CHRiSTOVICH

909 Poydras Street 2300 Pan American Life Center

Suite 2300 601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70130

BLAKE G. ARATA MOISE W. DENNERY

201 St. Charles Avenue 601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130 New Orleans, LA 70130

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEYS GENERAL

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

_ ATTORNEY GENERAL

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

(504) 568-5575

August 25th, 1988

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

or call collect (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

1. Did Congress intend the word “ representatives”

as used in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2(b) as amend

ed, 42 TT.S.C. § 1973, to include judges who are selected by

a state judicial electoral process!

11

LIST OF PARTIES

The parties to the proceedings below were:

The Petitioners:

EDWIN W. EDWARDS, in his

capacity as Governor of the

State of Louisiana; snb 110m BUDDY ROEMER

JAMES H. BROWN, in his

capacity as Secretary of

the State of Louisiana; sub nom FOX McKEITHEN

JERRY M. FOWLER, in his

capacity as Commissioner

of Elections of the State

of Louisiana

The Respondents:

RONALD CHISOM

MARIE BOOKMAN

WALTER WILLARD

MARC MORIAL

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/

EDUCATIONAL CRUSADE

[a non-profit corporation comprised of Orleans Par

ish black registered voters active in voting rights is

sues. On information and belief, petitioners assert

that this corporation has no parent, subsidiaries or

affiliates.]

HENRY A. DILLON, III

Ill

QUESTION PRESENTED ........................................ i

LIST OF PARTIES ............... ........... ........................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS..................... .................. ...... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................... ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ iv

OPINIONS BELOW ........ ............................................. 1

JURISDICTION ................................................. ..... ....... , 2

STATUTES INVOLVED .. ............... ......................... 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................... 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R IT ................ 4

I The United States Court Of Appeals For The

Fifth Circuit Has Decided An Important

Question Of Federal Law Which Has Not

Been, But Should Be, Settled By This Court 4

II The Term “ Representatives” Is Not A Syno

nym For “Elected Judicial Officials” .. ....... 12

III Louisiana’s Time Honored Tradition Of Elect

ing Its Judiciary Has Passed Justice Depart

ment Scrutiny .................. 17

IV This Court’s Decisions Make Clear That

Judges Are Not, And Should Not Be, Rep

resentatives ....................................................... 18

V The Fundamental Difference Between Rep

resentatives And Members Of The Judiciary

Is Deeply Rooted In This Country’s History 21

CONCLUSION .. ............................................................ 26

APPENDIX ..................................... ........... .............App. 1

TABLE OP CONTENTS

Page

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) ............ 19

Tyrone Brooks, et al. v. Glynn County, Georgia

Board of Elections, et al., Civil Action No. CV

288-146 (S.D.Ga. 1988) ........ ....................................... 9

California v. Carney, 471 U.S. 386 (1985) ........ .... ...... 15

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677 (1979) 20

Chandler v. Judicial Council, 398 U.S. 74 (1970) ......... 26

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988) ...passim

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F.Snpp. 183 (E.D.La.

1987) .......................... ...............................................passim

Chisom v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-4075,—

F.2d — (5th Cir. 1988) .................................... ........... 5

Clark v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-435 (A)

(M.D.La.) ........ .................. ......... ..............................6, 7, 8

Commodity Futures Trading Commission v.

Schor, — U.S. —, 106 S.Ct. 3245, 92 L.Ed.2d

675 (1986) ..................................... 15

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977) ........................... 18

Consumer Products Safety Comm’n v. GTE

Sylvania, 447 U.S. 102 (1980) .................................. 12

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) ................. ...... 18

Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951)................ 19

Dickerson v. New Banner Institute, Inc., 460 U.S.

103 (1983) .................................... 13

Escondido Mut. Water Co. v. La Jolla Indians,

466 U.S. 765 (1984) .....................................

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) ....

Page

13

21

15

V

League of United Latin American Citizens et al.

v. William Clements, et al., Civil Action No.

MO-88-CA-154 (W.D.Tex. 1988) ............................... 9

Mallory v. Eyrich, 666 F.Supp. 1060 (S.D.OMo 1987) ... 8

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1987) ........... 8

Martin v. Attain, 658 F.Supp. 1183 (S.D.Miss. 1987)... 6, 7

Members of the City Council of the City of Los

Angeles v. Taxpayers for Vincent, 466 U.S. 789

(1984) ........ _.............................. .... ........-......... ........... 16

Milwaukee v. Illinois, 451 U.S. 304 (1981)...................... 20

Mitchell v. W. T. Grant, 416 U.S. 600 (1974) ................ 15

Rita Rangel, et al. v. Jim Mattox, et al., Civil

Action No. B 88-053 (S.D.Tex, Brownsville

District 1988) ..................... ......................................... 9

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ................. .......19, 26

Rivera v. Minnich, — U.S. —, 107 S.Ct. 3001,

97 L.Ed.2d 472 (1987) ................. ...... ....................... 15

Schweiker v. Wilson, 450 U.S. 221 (1981) .................... 20

Southern Christian Leadership Conference of

Alabama, et ad. v. State of Alabama, et al., Civil

Action No. 88D462-N (M.D.Ala. 1988) .................... 8

Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153

(1978)-........... 26

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)........ .......... ... 8

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) ...................... 19

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ........................ 19

Paul L. Williams, et al. v. State Board of Elections,

et al., Civil Action No. 88C-2377 (N.D.I11. 1988) ....... 9

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

C on stitu tion al , S tatutory and R egulatory

P rovision s:*

U nited S tates S t a t u t e s :

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) .................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. § 1331.................................. ..................... 2,3

28 U.S.C. § 1342 ................. .................................... 3

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ................................................... .... 2

28 U.S.C. § 2201 ................... ....... .................. .....-... 2, 3

28 U.S.C. § 2202 .......■................................................ 2, 3

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ... ................................. passim, *App. 1

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ........................................ ...... passim

L ouisiana C o nstitution :

1852 Constitution, Article 64.. ........ ...................... 17

1879 Constitution, Article 82 ......... ............. ........... 17

1898 Constitution, Article 87 ................................... 17

1913 Constitution, Article 87 ................. ................. 17

1921 Constitution, Article 7, § 9 ........ ......... ............ 17

1974 Constitution, Article 5, § 3 ....................3, ®App, 2

1974 Constitution, Article 5, § 4 ..............3,17, ®App. 2

1974 Constitution, Article 8, § 10B .................... 17

1974 Constitution, Article 14, § 16 ......... ............... 17

L ouisiana R evised S tatutes :

R.S. 13:101 ................................................ 3,17, »App. 3

R.S. 18:511B .............................. ...... ................... ..... ............ 6

* Where full text appears in the Appendix, the page

reference is preceded by the symbol ® .

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

V ll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

R ules :

Page

Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b) 6 .................................... ........... 2,4

B ooks :

A. Bickel, The Supreme Court and the Idea of

Progress (1978 Yale University Press edition).......24,25

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust (1980 Harvard

University Press hardbound edition) ............... ........ 24

L. Friedman, A History of American Law (Simon

& Schuster 1973 paperback edition) ..................... 24

Gr. White, The American Judicial Tradition (1978

Oxford University Press paperback edition) 21, 22,23, 24

National Center for State Courts, State Court

Organization 1987 July 1988 ....................................... 11

N ewspapeks :

New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 21, 1972 18

No.

o

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1988

---------------o----------------

BUDDY ROEMER, in his capacity as Governor of the State of

Louisiana; FOX McKEITHEN, in his capacity as Secretary of

State of Louisiana; and JERRY M. FOWLER, in his capacity

as Commissioner of Elections of the State of Louisiana,

Petitioners,

versus

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN, WALTER WILLARD,

MARK MORIAL, LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/EDUCA-

TION CRUSADE, and HENRY A. DILLON, III,

Respondents.

-o-

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

■---------------- o------------------

The petitioners, BUDDY ROEMER, in his capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana; FOX McKEITHEN,

in his capacity as Secretary of State of Louisiana; and

JERRY M. FOWLER, in his capacity as Commissioner of

Elections of the State of Louisiana, respectfully pray that

a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment and opin

ion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, entered in the above-entitled proceeding on Feb

ruary 29, 1988. A timely application for rehearing was

denied on May 27, 1988.

--------------- o---------------

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit is reported at 839 F.2d 1056, and is

reprinted in the Appendix hereto, App. 4, infra.

1

2

Denial of the Petition for Rehearing by the Fifth Cir

cuit is unreported. It is reprinted in the Appendix hereto,

App. 27, infra.

The opinion of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana is reported at 659 F.Supp. 183, and

is reprinted in the Appendix hereto, App. 28, infra.

--------------- o--------------- -

JURISDICTION

Invoking federal jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §'§ 1331

and 1343 and 42 U.S.C. ’§ 1973C, respondents brought this

suit in the Eastern District of Louisiana on May 1, 1986.

The respondents sought declaratory and injunctive relief

under 42 U.S.C. §'§ 1973 and 1983, as well as 28 U.S.C.

§'§ 2201 and 2202. The complaint was amended on Septem

ber 30th, 1986.

A motion by petitioners to dismiss for failure to state

a claim upon which relief can be granted pursuant to Rule

12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure was

filed on March 18, 1987. The district court granted the

motion to dismiss on May 1, 1987, amended July 10, 1987,

659 F.Supp. 183 (E.D.La 1987). App. 28, infra.

On May 7, 1987, respondents appealed this dismissal

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit. On February 9, 1988 the dismissal decision of the

district court was reversed and the case was remanded,

839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988). App. 4, infra. Rehearing

was denied May 27,1988. App. 27, infra.

The jurisdiction of this Court to review the judgment

of the Fifth Circuit is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

o

3

STATUTES INVOLVED

The following constitutional and statutory provisions

involved have been printed in the Appendix.

United States Statutes:

Voting Rights Act

42 U.S.C. § 1973

Louisiana Constitution:

Judicial Branch

Article 5

Sections 3 and 4

Louisiana Revised Statutes:

Supreme Court District; justices

R.S. 13:101

--------------- o---------------

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondents brought this suit in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana on be

half of all black registered voters in Orleans Parish, ap

proximately 135,000 people. The suit challenged the at-

large election of two justices to the Louisiana Supreme

Court from the parishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaque

mines and Jefferson as being in violation of the 1965 Vot

ing Rights Act, as amended, because of alleged dilution of

the voting strength of the respondents. The action was

for declaratory and injunctive relief, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973

and 1983. Jurisdiction in the district court was asserted

under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343 as well as 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973C. Respondents also sought relief under 28 U.S.C.

■§§ 2201 and 2202. Respondents sought the division of the

First Supreme Court District into two districts, one to be

comprised of the parishes of Jefferson, Plaquemines and

St. Bernard and the other of Orleans Parish where blacks

constituted 51.6% of the registered voters.

4

Petitioners filed a Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b) (6) motion to dis

miss for the failure of the respondents to state a claim

upon which relief could be granted. The district court

agreed with petitioners’ contention that it was not the in

tention of Congress to apply the word “ representatives”

in Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, to em

brace members of the judiciary. The district court drew a

distinction between the impartial functions performed by

the judiciary without a constituency and. the functions per

formed by the representatives who are not expected to be

impartial but rather reflective of the needs and wishes of

their constituency. The district court opinion is reported

at 659 F.Supp. 183 (EJD.La 1987), and printed in the Ap

pendix. App. 28, infra.

The respondents appealed to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, where the judgment of

the district court was reversed and the case was remanded

because the court concluded that section 2 does apply to

the election of state court judges. Ghisom v. Edwards,

839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988). App. 4, infra.

A timely filed application for rehearing was denied

on May 27,1988. App. 27, infra.

—------------ o---------------

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

The United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

Has Decided An Important Question Of Federal

Law Which Has Not Been, But

Should Be, Settled By This Court

This case is one of national importance, as the judic

iary selection statutes of forty-two states are affected by

the decision below. Of these, thirty-six states employ a

direct election process, and six states employ a retention

5

election process. Only eight states employ either a guber

natorial or legislative selection process. Further, the At

torney General of the United States has certified this to

be a case of general public importance.1

There are several pending- cases concerning which

guidance by this Court is needed. Subsumed within the

question presented is, if Section 2 of the Voting Eights

Act is applicable, must the results test be applied in de

termining the existence of a violation ? Is the results test

and corresponding relief compatible with the inappropri

ateness of applying the one man one vote test to the judic

iary? If there is a violation does it permeate the entire

judicial system? If a state, such as Louisiana, chooses to

change its judicial selection process from an electoral sys

tem to one of appointment and/or merit, must it preclear

such a change when most of the other forty-two states

that elect judges need not preclear a change ? 1

1 On remand the district court granted a preliminary injunc

tion to prevent a scheduled election relating to a Louisiana Su

preme Court First District position, the term for which expires

on December 31,1988. In his July 7, 1988 Opinion regarding the

preliminary injunction, Judge Schwartz stated, in pertinent part:

While this Court adheres to its original opinion, the Fifth

Circuit has spoken; this Court is bound by the Fifth Circuit's

holding, unless and until that holding is either expressly

or tacitly overruled judicially by either the Fifth Circuit or

the Supreme Court or legislatively by Congress.

Opinion, pages 16-17, July 7, 1988. Ronald Chisom, et a/, v. Ed

win Edwards, et at, Civil Action No. 86-4075, United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Upon the district court's refusal to grant a stay, an expedited

appeal was perfected to the court of appeals where a stay of the

preliminary injunction was granted to permit qualification to

occur. Thereafter, the Fifth Circuit vacated the injunction. After

this ruling the Attorney General of the United States moved to

intervene in this case, asserting and certifying it to be one of

genera! public importance. The motion was granted. The Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals issued its reasons for vacating the in

junction on August 19, 1988. These reasons are reproduced in

the appendix at App. 44.

6

Illustrative as to the need for instructive guidance

from this Court are two district court cases within the

Fifth Circuit reaching contrary results. In the case of

Martin v. Attain, 658 F.Supp. 1183 (S.D.Miss. 1987), the

district judge has ruled that there need be changes only

in those districts where a violation is found, and that the

district court will fashion the remedy. In contrast, in the

case of Clark v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-435~(A)

(M.D.La.), which affects all of Louisiana’s district and

intermediate appellate courts, the district judge has en

joined all judicial elections to these courts, even in dis

tricts where the plaintiffs presented no evidence whatso

ever, and has enjoined the issuance of commissions to

those who have been elected without opposition.2 This

district judge has asserted that he will turn the matter

over first to the Legislature to fashion a remedy, and if it

does not do so, he will fashion the remedy. This same

judge has decided that a violation as proved in any judic

ial district will require that the entire judicial system be

changed, despite the absence of violations in many other

districts.3 The Clark judge’s position appears to be

2 According to Louisiana law, an unopposed candidate is auto

matically elected and is to be granted a commission. The ap

plicable statute states:

ELECTION OF UNOPPOSED CANDIDATES FOR PUBLIC

OFFICE

If, after the close of the qualifying period for candi

dates in a primary election, the number of candidates for

a public office does not exceed the number of persons to

be elected to the office, the candidates for that office, or

those remaining after the withdrawal of one or more candi

dates, are declared elected by the people, and their names

shall not appear on the ballot in either the primary or the

genera! election.

LA R.S. 18:511B.

Because of my conviction that there are legally signifi

cant differences between judicial elections and legislative

(Continued on following page)

7

(Continued from previous page)

elections, it is my view that the remedy for Section 2 vio

lations which are produced by the judicial election system,

is to change the system, not to create sub-districts within

district courts. Consequently, I conceive it to be my duty,

having found violations, to enjoin all district, family court

and court of appeal elections until the governor of Louisiana

and the Louisiana legislature have had an opportunity to

make changes in the judicial election system that will avoid

such violations. Hence, I decline to follow the lead of

Judge Barbour in Martin v. Ailain, 658 F.Supp. 1183 (S.D.

Miss. 1987) in confining the remedy to those specific dis

tricts in which a violation was found.

Unreported Ruling on Motion for Preliminary Injunction, page

5, August 10, 1988. Clark v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-435(A)

(M.D.La.).

The following Order was signed and filed on August 11,

1988:

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the Governor, the Secre

tary of State, the Attorney General, and all other election

officials, in their official capacities, as well as their attorneys,

agents and representatives are hereby preliminarily enjoined

from conducting any family court, district court, or court of

appeal election which was scheduled for the October 1,

1988 (primary) and November 8, 1988 (general) elections,

whether specifically enumerated or not and no certification

shall issue to any candidate who qualified for any such elec

tion without opposition.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, August 11, 1988.

Unreported Order, August 11, 1988. Clark v. Edwards, Civil

Action No. 86-435(A) (M.D.La.).

Even though no specific Section 2 violation may exist in a

particular district at this time, the system employed by the

state will allow the creation of a violation, given time.

The remedy is to revise the system— to cast about for

alternative procedures under which black voters would have

a better chance to elect judicial candidates of their choice.

There are many alternatives which may be considered.

This court has no preconceived notion as to what changes

the Governor and the Legislature ought to make. This court

(Continued on following page)

clearly at odds with this Court’s decision in Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

The inquiry into the existence of vote dilution

caused by submergence in a multimember district is

district-specific. When considering several separate

vote dilution claims in a single case, courts must not

rely on data aggregated from all the challenged dis

tricts in concluding that racially polarized voting

exists in each district.

Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 59 n. 28.

Other jurisdictions where the question presented here

was, or is, at issue include:

OHIO:

where the United States District Court, S.D.Ohio,

W.D., held the Voting Eights Act to be inappli

cable to the judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich 666

F.Supp. 1060 (1987). On appeal the Sixth Cir

cuit Court of Appeals reversed and held the Act

applicable to the judiciary and remanded the case.

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1987);

ALABAMA:

where the case of Southern Christian Leadership

Conference of Alabama, et al. v. State of Ala-

8

(Continued from previous page)

is simply convinced that the present system of electing fam

ily court, district court, and court of appeal judges in Louisi

ana has produced violations of Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and that it will continue to produce violations unless

it is changed.

Accordingly, the preliminary injunction previously

issued will be made permanent and will be expanded to

enjoin all family court, district court, and court of appeal

elections until revisions in the eiectorial[sic] process are

made.

Unreported Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, pages 41-

42, August 15, 1988. Clark v. Edwards, Civil Action No. 86-435

(A) (M.D.La.).

9

bama, et al., Civil Action No. 88D462-N, was filed

on May 11, 1988 in the United States District

Court for the Middle District of Alabama, North

ern Division and is pending;

GEORGIA:

where the case of Tyrone Brooks, et al. v. Glynn

County, Georgia Board of Elections, et al., Civil

Action No. CV288-146, was filed on July 18, 1988

in the United States District Court for the South

ern District of Georgia, Brunswick Division and

is pending;

ILLINOIS:

where the case of Paul L. Williams, et al. v. State

Board of Elections, et al., Civil Action No. 88C-

2377, was filed on March 22, 1988 in the United

States District Court for the Northern District

of Illinois, Eastern Division and is pending.4

TE XAS:

where the case of Rita Rangel, et al. v. Jim Mat

tox, et al., Civil Action No. B 88-053, was filed on

May 24, 1988 in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Texas, Brownsville

District, and the case of League of United Latin

American Citizens et al. v. William Clements,

et al., Civil Action No. MO-88-CA-154, was filed

on July 11, 1988 in the United States District

Court for the Western District of Texas, Mid-

land-Odessa Division, and are both pending.

Litigation is anticipated in several other jurisdictions, in

cluding an additional suit in Louisiana relating to city

court judges.

4 This case affects the largest court system in the country [and

perhaps the world], 201 judges, all of whom were ordered by

John F. Grady, Chief Judge, to be joined as parties on August 4,

1988.

10

The consideration by this Court of the question pre

sented in this petition will be of invaluable assistance to

all of the federal district courts, with the exception of the

states which have adopted a judiciary selection system

embracing solely one of appointment, namely Delaware,

Hawaii, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey,

Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia. It would also be

helpful for all of the circuit courts, with the exception of

the District of Columbia Circuit, for there are from one to

several states covered within each circuit where there are

judicial elections or retention elections selection systems.

These states by circuit are:

First Circuit Maine

Second Circuit Connecticut

New York

Third Circuit Pennsylvania

Fourth Circuit Maryland

North Carolina

South Carolina

West Virginia

Fifth Circuit Louisiana

Mississippi

Texas

Sixth Circuit Kentucky

Michigan

Ohio

Tennessee

Seventh Circuit Illinois

Indiana

Wisconsin

Eighth Circuit Arkansas

Iowa [Retention election]

Minnesota

Missouri [Retention election]

Nebraska [Retention election]

North Dakota

South Dakota

11

Ninth Circuit

Tenth Circuit

Eleventh Circuit

Alaska [Retention election]

Arizona

California

Idaho

Montana

Nevada

Oregon

Washington

Colorado [Retention election]

Kansas

New Mexico

Oklahoma

Utah [Retention election]

Alabama

Florida

Georgia

State Court Organization 1987—National Center for State

Courts, July 1988. Selection process of appellate and trial

court judges [tables 7 and 20].

If the Court does not take this case, chaos will ensue.

There are already 7 states which are facing litigation that

may require the restructuring of their judicial selection

election systems, and it is merely a matter of time until

the remaining 35 states that elect judges will be faced with

similar suits. For this Court to wait until all such litiga

tion wends its way through the lower courts will create

havoc in the judicial process. The Fifth Circuit’s opinion

vacating the injunction in this case, App. 44 infra, explains

at length some of the complicating factors involved in re

structuring a state’s judiciary. Finally, when this Court

ultimately decides to take a case, it may require those

states that have changed their judicial system to endure

another upheaval because of this Court’s ultimate ruling.

To have judicial elections enjoined throughout the

United States and to have judges serving and deciding

cases under a cloud of litigation will discredit the judicial

process. Further, it will make it impossible for states to

12

add judges to handle expanded case loads and to replace

judges when an existing position becomes vacant by rea

son of death, retirement or incapacity. It would be far

better for this Court to determine now whether Section 2

applies to the judiciary, and, if so, to establish and pro

mulgate the applicable criteria to prove a Section 2 viola

tion involving judicial elections.

The question, though extremely serious, is not compli

cated. If substantially all of the forty-two states with a

judiciary selection process based upon an election or a re

tention election, must restructure their systems to conform

with the Voting Eights Act, then the sooner the legisla

tures of the various states may be so authoritatively in

formed by this Court, the better for an ultimate survival

of the state court judiciary. Changes do not come about

easily.

II

The Term “ Representatives” Is Not

A Synonym for 1 ‘Elected Judicial Officials”

The term ‘ ‘ representatives’ ’ as used in Section 2(b)

of the Voting Rights Act should not be equated with

“ elected judicial officials,” language which appears no

where in the statute.

This Court has laid down definitive guidelines for

construing language which appears in Congressional Acts.

In Consumer Products Safety Comm’n v. GTE Syl-

vania, 447 U.S. 102 (1980), the Court stated:

We begin with the familiar canon of statutory con

struction that the starting point for interpreting a

statute is the language of the statute itself.

Id. at 108. Four years later, in furtherance of this con

cept of construction, the Court held:

Since it should be generally assumed that Congress

expresses its purposes through the ordinary meaning

of the words it uses, we have often stated that

“ ‘ [ajbsent a clearly expressed legislative intention

13

to the contrary, [statutory] language must ordinarily

be regarded as conclusive.’ ”

Escondido Mut. Water Co. v. La Jolla Indians, 466 U.S.

765, 773 (1984) [Citations omitted].

In Dickerson v. New Banner Institute, Inc., 460 U.S.

103 (1983), the Court said:

[W ]e state once again the obvious when we note that,

in determining the scope of a statute, one is to look

first at its language. . . . If the language is unam

biguous, ordinarily it is to be regarded as conclusive

unless there is “ ‘ a clearly expressed legislative in

tent to the contrary. ’ ’ ’

Id. at 853 [Citations omitted].

The term “ representatives” refers to those who serve

a specialized constituency and whose role is to represent

the needs and interests of that constituency. The term

“ representatives” has never been commonly accepted as

including the judicial branch; indeed, the reverse is true—

namely, the judicial branch always has been treated as

separate and distinct from the other two representative

arms of government.

A representative of a district, be it federal, state, or

local, exists to serve and favor his or her constituency,

while hopefully also working for the good of the govern

mental jurisdiction as a whole. United States representa

tives are expected to help get government contracts for

their districts; no one, however, would expect a federal

judge to uphold such a contract citing as a reason the need

of his area for governmental business. State legislators

are expected to seek bridges and roads for their districts;

no one, however, would expect a state judge to mandate

that such bridges and roads be built because the people

want them. City eouneilmen are expected to promote

drainage projects for their council districts; no one, how

14

ever, would expect a city judge to require them to keep Ms

voters happy.

Judges thus are not representatives; further, they

should not be representatives. The larger the constitu

ency, the less parochial pressures can be brought to bear.

An advantage to at-large elections for judges is that

judges can make the difficult decisions without undue fear

of dissatisfaction in the electorate. A judge would be

much less likely to vote against the residents of a neigh

borhood on a zoning issue if that judge was elected solely

by that neighborhood. Justice ought to be identical

throughout a judicial system; electing judges from neigh

borhoods, however, might make for a system of individ

ualized justice currently foreign to the United States. Ad

mittedly, many problems could be cured on appeal; how

ever, it can be extremely difficult to reverse a detailed

record of fact-finding even when the facts have been

slanted. Further, the respondents here seek to make ap

pellate districts smaller also, again lessening the number

and mix of a judge’s constituency.

An independent judiciary is crucial to the proper

functioning of a constitutional form of government. The

framers of our Constitution insulated the federal judiciary

from the day-to-day whims, pressures, and reactions of

other branches of government. The framers’ mechanism

to achieve an independent judiciary was appointment for

life with the advice and consent of the Senate for Article

III judges; however, constitutional jurisprudence has not

suggested that elected state judges should be any less in

dependent. Indeed, numerous constitutional rights are

protected only through the existence of an independent

judiciary.

The Court has long recognized that the unique posi

tion of a state judiciary (as opposed to other state of

ficers, officials, and elected representatives) affords con

stitutional protections to all. For example:

15

1. It is the existence of an independent judicial of

ficer (whether elected or appointed) examining

requests for search warrants that protects the

rights against unlawful searches and seizures.

Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) ; Cali

fornia v. Carney, 471 U.S. 386 (1985) (dicta).

2. It is the existence of an independent judicial of

ficer, and that judge’s review and evaluation of

documents, that makes a prejudgment seizure

lawful and not violative of due process rights in

civil actions. Mitchell v. W. T. Grant, 416 U.S.

600 (1974). In Mitchell, the Supreme Court spe

cifically held Louisiana’s prejudgment seizure

statutes constitutional because of the scrutiny of

Louisiana District Court Judges.

3. The Supreme Court, in discussing Article III,

Section 1’s guarantee of an independent and im

partial adjudication by a federal judiciary, has

read prior cases as indicating that the existence

of an independent judiciary “ serves to protect

primarily personal, rather than structural, in

terests.” Commodity Futures Trading Commis

sion v. Schor, — U.S. —, at —, 106 S.Ct. 3245, at

3256, 92 L.Ed.2d 675 at 691 (1986). Likewise,

state judges protect the personal interest of the

litigants, not structural interests of the State or

of the electorate.

4. In paternity proceedings, the State as an entity

may have one set of interests, but it is the exist

ence of an independent judiciary that protects the

rights of litigants, not any state interest per

ceived by members of the legislative or executive

branch. See Rivera v. Minnich, — U.S. —, 107

S.Ct. 3001, 97 L.Ed.2d 473, 481 n. 8 (1987).

5. Local legislative and executive officials may seek

to pass and enforce ordinances prohibiting the

posting of signs on public property. While pure

ly aesthetic objectives may be considered and en-

16

acted by local elected officials, the enforceability

and constitutionality of those laws must be as

certained by an independent judicial assessment

of the substantiality of the government’s interest

and by a court’s scrutiny of aesthetics-based re

strictions on speech. See, e.g., Members of the

City Council of the City of Los Angeles v. Tax

payers’ for Vincent, 466 U.S. 789 (1984).

These are but a few examples of the importance of

an independent judiciary in the range of constitutional is

sues that affect the life of every citizen of this country.

Congress, had it wanted specifically to include judges

under Section 2(b) of the Voting Eights Act, could have

done so by substituting the term “elected officials” for the

term “ representative” ; it did not do so. In a representa

tive form of government, such as ours, it is always true

that a “ representative” is an “ elected official” ; however,

the converse is not always true.

The 1982 Amendment to the Voting Rights Act of

1965 added language describing those circumstances that

would constitute a violation of Section 2. Section 2(b)

expressly states that a violation exists when “ [members

of a protected class] have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives of their choice.”

Representatives have a constituency which numbers

in the hundreds to hundreds of thousands, to each of whom

they owe fidelity and from each of whom they are likely,

sooner or later, to receive correspondence or a telephone

call or even perhaps a personal visit.

Judges have but one constitutency, the blindfolded

lady with scales, sword and shield.

17

III

Louisiana’s Time Honored

Tradition Of Electing Its Judiciary

Has Passed Justice Department Scrutiny

The statutes and laws concerning the Louisiana ju

dicial electoral system are not, in whole or part, prod

ucts of racial discrimination. Louisiana first introduced

its judicial selection system 136 years ago in its 1852

Constitution, Article 64. The parishes of Orleans, St.

Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson have had two jus

tices on the Louisiana Supreme Court since Louisiana’s

1879 Constitution Article 82, adopted 109 years ago. See

1898 Constitution Article 87; 1913 Constitution Article

87; 1921 Constitution Article 7 §9 ; 1974 Constitution

Article 5, § 4.

The 1974 Constitution, Article 14, § 16, relegated the

listing of districts formerly in Article 7, § 9 of the 1921

Constitution to the statutes. This statute is LA. R.S.

13:101.

The 1974 Constitution was precleared by the Justice

Department of the United States of America on Novem

ber 26, 1974 [thus after the adoption of the Voting Rights

Act] except for Article 8 § 10B, which was subsequently

precleared on June 6, 1983 [thus after the 1982 amend

ment to the Voting Rights Act].

In Orleans Parish blacks have always had the op

portunity of voting for the candidates of their choice. In

1972 both positions on the Louisiana Supreme Court for

the First Supreme Court District were vacant. Two blacks,

Judge Ortique and a Mr. Amadee, ran for election, one

for each of the seats, with the following results:

Total Orleans

Ortique 27,326 21,224

Calogero 66,411 33,700

Redmann 21,865 10,240

Sarpy 74,320 34,011

18

Total Orleans

Amedee 11,722 8,847

Marcus 78,520 47,725

Bossetta 35,267 19,115

Garrison 51,286 25,437

Samuel 25,659 6,042

New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 21, 1972 (on file in

the Louisiana Supreme Court Judicial Administrator’s

office).

Judge Ortique thus received in Orleans Parish 21.4%

of the vote, and Mr. Amadee received 8.26% of the votes

in Orleans Parish. In 1972 blacks represented 33.35% of

the registered voters in Orleans Parish; therefore, the

majority of the blacks voted for the white candidate in

one race, and a substantial percentage in the other.

IV

This Court’s Decisions Make Clear That

Judges Are Not, And Should Not Be, Representatives

The Supreme Court’s use of the word “ representa

tives” over the years shows that the Court considers the

term to refer to legislators or administrators as opposed

to judges. For example, in Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S.

109 (1986), the Court used the terms “ representative” and

“ legislator” interchangeably:

Rather, it is that one electoral district elects a single

representative and another district of the same size

elects two or more—the elector’s vote in the former

district having less weight in the sense that he may

vote for and his district be represented by only one

legislator, while his neighbor in the adjoining district

votes for and is represented by two or more.

Id. at 123.

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977), a voting rights

case, also uses the terms interchangeably:

19

The Equal Protection Clause requires that leg

islative districts be of nearly equal population, so that

each person’s vote may be given equal weight in the

election of representatives.

Id. at 416; accord, White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 764,

779 (1973).

In Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), the Court,

while speaking of state legislatures, stated that those in

dividuals elected to the legislative branch were the peo

ple’s representatives:

As long as ours is a representative form of govern

ment, and our legislatures are those instruments of

government elected directly by and directly represen

tative of the people, the right to elect legislators in

a free and unimpaired fashion is a bedrock of our

political system. . . . But representative government is

in essence self-government through the medium of

elected representatives of the people, and each and

every citizen has an inalienable right to full and

effective participation in the political processes of

his State’s legislative bodies.

Id. at 562, 565. The Court went on to call the state legis

lature “ the only instrument of state government directly

representative of the people.” Id. at 576; accord, Whit

comb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124,141 (1971).

In his concurring opinion in Dennis v. United States,

341 U.S. 494 (1951), Justice Frankfurter flatly stated:

“ Courts are not representative bodies. They are not de

signed to be a good reflex of a democratic society.” Id.

at 517, 525 (Frankfurter, J., concurring in the judgment).

In Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968), an

other voting rights case, the Court made clear the appli

cability of the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to local subdivisions, again using the term

“ representative.” The Court noted that state legislators

20

enact many laws but do not govern countless matters of

local concern, which are left to the local level to decide:

What is more, in providing for the governments of

their cities, counties, towns, and districts, the States

characteristically provide for representative govern

ment—for decisionmaking at the local level by rep

resentatives elected by the people.

Id. at 481. The defendants had argued that the County

Commissioners Court was not sufficiently legislative and

that therefore unequal districts were permissible. The

Court, however, noted that many of its functions were leg

islative and that the County Commissioners Court was a

general governing body:

[T]he court does have power to make a large number

of decisions having a broad range of impacts on all

the citizens of the county. It sets a tax rate, equalizes

assessments, and issues bonds. It then prepares and

adopts a budget for allocating the county’s funds, and

is given by statute a wide range of discretion in

choosing the subjects on which to spend.

Id. at 483. Because of these general powers, the County

Commissioners Court could not have unequal districts.

Never is there any intimation in the opinion that a purely

judicial body would be judged the same way by the Court.

In Milwaukee v. Illinois, 451 U.S. 304 (1981), the

Court contrasted the role of the courts with that of Con

gress, a representative body:

The enactment of a federal rule in an area of nat

ional concern, and the decision whether to displace

state law in doing so, is generally made not by the

federal judiciary, purposefully insulated from elec

toral pressures, but by the people through their elect

ed representatives in Congress.

Id. at 312-13; accord, Schweiker v. Wilson, 450 U.S. 221,

230 (1981); Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S.

21

677, 696-97 (1979) (“ it is always appropriate to assume

that our elected representatives . . . know the law.” ).

In arguing that the Supreme Court should not invali

date a Connecticut birth control statute, Justice Stewart

stated:

It is the essence of judicial duty to subordinate our

own personal views, our own ideas of what legislation

is wise and what is not. If, as I should surely hope,

the law before us does not reflect the standards of the

people of Connecticut, the people of Connecticut can

freely exercise their true Ninth and Tenth Amend

ment rights to persuade their elected representatives

to repeal it.

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 530-31 (1965) (Stew

art, J., dissenting) (emphasis esupplied).

V

The Fundamental Difference Between

Representatives And Members Of The Judiciary

Is Deeply Rooted In This Country’s History

The legal history of this nation demonstrates a clear

and concise distinction as between one who is a represen

tative of the people and one who dedicates his life to a

different calling, that of the judiciary.

The idea that judges are to be “ representatives” is

totally foreign to American legal history. Instead, this

country was founded, and has endured, on the principle

of an independent judiciary free of the sort of constituent

pressures on, and parochial viewpoints required of, legis

lators.

The history of the American judiciary was traced by

Professor G. Edward White in The American Judicial

22

Tradition.5 Professor White began by stating that during

colonial times judges “were agents of the provincial gov

ernment” with “ a wide range of petty powers but of little

independence.” Judicial Tradition!.

Beginning with Chief Justice John Marshall, the

American judicial tradition emerged. A core element of

that tradition has always included “ a measure of true in

dependence and autonomy for the appellate judiciary from

the other two branches of government.” Judicial Tradi

tion 9. Professor White summarized Chief Justice Mar

shall’s views concerning the judiciary as follows :

An independent judiciary was logically the ultimate

necessity in Marshall’s jurisprudence, the culmina

tion of his beliefs about law and government. He

sought to show that judicial independence as not mere

ly a side effect of federalism but a first principle of

American civilization. . . . Against the potential chaos

attendant on mass participatory democracy, republi

cans erected the institutional buffers of legislative

representatives and an independent judiciary. The

excesses of the people were moderated by representa

tion, a process by which their passionate demands were

reformulated by an enlightened and reasonable class

of public servants. The need of the populace for an

articulation of their individual rights under law was

met by the presence of a body of judges not beholden

to the masses in any immediate, partisan sense.

Judicial Tradition 18, 20.

Chief Justice Marshall’s vision of the American judi

cial tradition was not unique. Alexander Hamilton “ en

visaged judicial review as an exercise in politics through

which an independent judicial elite could temper the dem-

5 Citations are hereinafter abbreviated as Judicial Tradition.

Page references refer to the 1978 Oxford University Press paper

back edition.

oeratic excesses of legislatures by affirming the repub

lican political balances inherent in the Constitution. ’ ’

Judicial Tradition 24. Some among the Founding Fathers

thought an independent judiciary necessary because “ even

a government made up of the people’s representatives was

not a sufficient buffer against the excesses of the mob.”

Judicial Tradition 320.

This American judicial tradition has not been applic

able only to the federal judiciary. Professor White com

mented that the state constitutions “ were patterned on

the federal Constitution, with its tripartite division of

powers.” Judicial Tradition 109. James Kent, Chief

Judge of the New York Supreme Court and later Chan

cellor of New York, “ viewed the judiciary as a buffer be

tween established wealth and the excessively democratic

legislature. ’ ’ Judicial Tradition 112. Much more re

cently, Roger Traynor, Chief Justice of the California Su

preme Court, wrote that judges “ enjoyed a ‘ freedom from

political and personal pressures and from adversary bias’

[and that] [t]heir ‘ environment for work’ was ‘ indepen

dent and analytically objective.’ ” Judicial Tradition 296,

quoting Traynor, ‘ ‘ Badlands in an Appellate Judge’s

Realm of Reasons,’ ’ 7 Utah L. Rev. 157, 167, 168 (1960).

Professor White traced “ modern liberalism’ ’ trends

throughout the Twentieth Century. According to this

political theory, judges “ were not, by and large, repre

sentatives of the people, and their nonpartisan status in

sulated them from the waves of current opinion.” Judi

cial Tradition 320. Legislatures on the other hand ‘ ‘ were

‘ representative of popular opinion’ and could ‘ canvass

a wide spectrum of views.’ ” Judicial Tradition 322. One

24

Twentieth Century Justice, Felix Frankfurter, has called

the judiciary the “ antidemocratic, unrepresentative”

branch of government.” Judicial Tradition 367.®

Legal theorists have also stated that judges are not

“ representatives.” Perhaps the most provocative book

to appear on judicial review during the last few years is

Democracy and Distrust by Professor John Hart Ely.6 7

Professor Ely contrasts the role of the courts with the

role of the representative branch of government, the legis

lative branch. He sought an approach to judicial review

“ not hopelessly inconsistent with our nation’s commit

ment to representative democracy.” Democracy and Dis

trust 41. In his book, Professor Ely developed a repre

sentation-reinforcing theory of judicial review in which

the non-representative branch, the judiciary, would re

view legislation to review the motivation of the represen

tative branch, the legislature, to make sure that the views

of all groups were represented in lawmaking. He con

cluded by stating that “ constitutional law appropriately

exists for those situations where representative govern

ment cannot be trusted.” Democracy and Distrust 183.

Professor Alexander Bickel spoke of the importance

of judicial independence in The Supreme Court and the

Idea of Progress :8

The restraints of reason tend to ensure also the in

dependence of the judge, to liberate him from the de-

6 Professor Lawrence Friedman also has written about the his

tory of a strong, independent judiciary in the federal system and

in state systems. L. Friedman, A History of American Law 116,

118 (Simon & Schuster 1973 paperback edition).

7 Page references are to the 1980 Harvard University Press hard

bound edition.

8 Citations are hereinafter abbreviated as Supreme Court and

Progress. Page references refer to the 1978 Yale University Press

paperback edition.

2 5

mands and fears—dogmatic, arbitrary, irrational,

self- or group-centered—that so often enchain other

public officials. They make it possible for the judge,

on some occasions, at any rate, to oppose against the

will and faith of others, not merely his own will or

deeply-felt faith, but a method of reaching judgments

that may command the allegiance, on a second thought

even of those who find a result disagreeable. The judge

is thus buttressed against the world, but what is per

haps more significant and certain, against himself,

against his own uatural tendency to give way before

waves of feeling and opinion that may be as momen

tary as they are momentarily overwhelming. . . .

The independence of the judges is an absolute

requirement if individual justice is to be done, if a

society is to ensure that individuals will be dealt with

in accordance with duly enacted policies of the society,

not by the whim of officials or of mobs, and dealt with

evenhandedly, under rules that would apply also to

others similarly situated, no matter who they might be.

Supreme Court and Progress 82, 84.

Professor Bickel contrasted the Court on the one hand

with the people and its representatives on the other, stat

ing, “ Virtually all important decisions of the Supreme

Court are the beginnings of conversations between the

Court and the people and their representatives.” Supreme

Court and Progress 91.

Supreme Court and Progress also contains much ma

terial on reapportionment. Supreme Court and Progress

35, 158-59, 168-73. Never in that discussion is there any

intimation that redistricting of the courts ought to be

considered. That notion would run counter to his strong

argument for judicial independence.

-o

2 6

CONCLUSION

This Court has always recognized the importance of

an independent judiciary. This Court has held that,

“ There can, of course, he no disagreement among us as to

the imperative need for total and absolute independence

of judges in deciding cases or in any phase of the de

cisional function.” Chandler v. Judicial Council, 398 U.S.

74, 84 (1970). In a dissent in the same case, Justice Doug

las stated, “ An independent judiciary is one of this Na

tion’s outstanding characteristics.” Id. at 136 (Douglas,

J., dissenting).

A quarter of a century ago this Court declared,

“ Legislators represent people, not trees or acres.” Rey

nolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 562 (1964). Judges, on the

other hand, must consider the interests of people and of

trees (as well as snail darters, see Tennessee Valley Au

thority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978)). Unlike legislators,

judges are not “ instruments of government elected di

rectly by and directly representative of the people.” 377

U.S. at 562. Making judges representatives would do vio

lence to (and perhaps destroy) the American concept of an

independent judiciary.

For the foregoing reasons, a writ of certiorari should,

therefore, be granted to review and ultimately reverse the

decision below.

All of the above and foregoing is thus respectfully

submitted.

27

ROBERT G. PUGH

Counsel of Record

ROBERT G. PUGH, JR.

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

(318)

M. TRUMAN W OODW ARD,

JR.

909 Poydras Street

Suite 2300 „

New Orleans, LA 70130

BLAKE G. ARATA

201 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

SPECIAL ASSISTANT

>27-2270

A. R. CHRISTOVICH

2300 Pan American Life

Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

MOISE W. DENNERY

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

ATTORNEYS GENERAL

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Louisiana Department of justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

(504) 568-5575

United States Statutes

42 § 1973. Denial or abridgement of right to vote on ac

count of race or color through voting qualifications or

prerequisites; establishment of violation

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to vot

ing or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed

or applied by any State or political subdivision in a man

ner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right

of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the guarantees set

forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title, as provided in

subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is

established if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to nomination

or election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity than other members of

the electorate to participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice. The extent to

which members of a protected class have been elected to

office in the State or political subdivision is one circum

stance which may be considered: Provided, That nothing

in this section establishes a right to have members of a

protected class elected in numbers equal to their propor

tion in the population.

App. 1

A p p . 2

Louisiana Constitution

Article 5. Judicial Branch

Section 3. Supreme Court; Composition; Judgments;

Terms

Section 3. The supreme court shall he composed of

a chief justice and six associate justices, four of whom

must concur to render judgment. The term of a supreme

court judge shall be ten years.

Section 4. Supreme Court; Districts

Section 4. The state shall be divided into at least six

supreme court districts, and at least one judge shall be

elected from each. The districts and the number of judges

assigned to each on the effective date of this constitution

are retained, subject to change by law enacted by two-

thirds of the elected members of each house of the legis

lature.

A p p . 3

Louisiana Revised Statutes

R.S. 13.-101 Supreme court district; justices

The state shall be divided into six supreme court dis

tricts and the supreme court shall be composed of justices

from the said districts as set forth below:

(1) First district. The parishes of Orleans, St.

Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson shall compose the

first district, from which two justices shall be elected.

(2) Second district. The parishes of Oaddo, Bos

sier, Webster, Claiborne, Bienville, Natchitoches, Red

River, DeSoto, Winn, Vernon, and Sabine shall compose

the second district, from which one justice shall be elected.

(3) Third district. The parishes of Rapides, Grant,

Avoyelles, Lafayette, Evangeline, Allen, Beauregard, Jef

ferson Davis, Calcasieu, Cameron, and Acadia shall com

pose the third district from which one justice shall be

elected.

(4) Fourth district. The parishes of Union, Lincoln,

Jackson, Caldwell, Ouachita, Morehouse, Richland, Frank

lin, West, Carroll, East Carroll, Madison, Tensas, Concor

dia, LaSalle, and Catahoula shall compose the fourth dis

trict, from which one justice shall be elected.

(5) Fifth district. The parishes of East. Baton

Rouge, West Baton Rouge, West Feliciana, East Feliciana,

St. Helena, Livingston, Tangipahoa, St. Tammany, Wash

ington, Iberville, Pointe Coupee, and St. Landry shall com

pose the fifth district, from which one justice shall be

elected.

(6) Sixth district. The parishes of St. Martin, St.

Mary, Tberia, Terrebonne, Lafourche, Assumption, Ascen

sion, St. John the Baptist, St. James, St, Charles, and Ver

milion shall compose the sixth district from which one

justice shall be elected.

A p p . 4

Ronald CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

v.

Edwin EDWARDS, in his capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana,

et al., Defendants-Appellees.

No. 87-3463.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Feb. 29, 1988.

Black registered voters in Orleans Parish of Louisi

ana brought suit challenging constitutionality of present

system of electing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

First Supreme Court District. The United States Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, Charles

Schwartz, Jr., J., 659 F.Supp. 183, dismissed, and voters

appealed. The Court of Appeals, Johnson, Circuit Judge,

held that: (1) judicial elections are covered by Voting

Rights Act section which prohibits any law or procedure

which has effect of denying or abridging right to vote on

basis of race, and (2) complaint by black registered voters

challenging current at-large system of electing state Su

preme Court Justices from their district established theory

of discriminatory intent and stated claim of racial dis

crimination under Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Reversed and remanded.

1. Elections 12(1)

Judicial elections are covered by Voting Rights Act

section which prohibits any law or procedure which has

effect of denying or abridging right to vote on basis of

A p p . 5

race. Voting Eights Act of 1965, §2, as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. § 1973.

2. Civil Rights 13.4(6)

Elections 7

Discriminatory purpose is prerequisite to recovery

under Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amends. 14,15.

3. Civil Rights 13.12(3)

Elections 7

Complaint by black registered voters challenging cur

rent at-large system of electing state Supreme Court Jus

tices from their district established theory of discrimina

tory intent and stated claim of racial discrimination un

der Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments; voters cited

history of purposeful official discrimination on basis of

race in state and existence of wide-spread racially polar

ized voting in elections involving black and white candi

dates, concluding that current election procedures for se

lecting Supreme Court Justices from their area diluted

minority voting strength. U.S.C.A. ConstAmends. 14, 15.

William P. Quigley, Ron Wilson, New Orleans, La.,

for plaintiffs-appellants.

Mark L. Gross, Justice Dept., Jessica Dunsay Silver,

Washington, D.C., for amicus U.S.

Pamela S. Karlan, Charles Stephen Ralston, New

York City, for Chisom Group.

A p p . 6

Michael H. Rabin, Baton Roage, La., Kendall L. Vick,

Asst. Atty. Gen., La. Dept, of Jastice, M. Trnman Wood

ward, Jr., New Orleans, La., for arnicas LDJA.

Michael B. Wallace, Jackson, Miss., Daniel J. Popeo,

Washington Legal Foandation, Washington, D.C., A.R.

Christovicli, Jr., Moise W. Dennery, New Orleans, La.,

for arnicas Washington Legal and Allied Ed.

John L. Maxey, II, Special Coansel, Stephen J. Kirch-

mayr, Deputy Atty. Gen., Hubbard T. Saunders, IY, Jack-

son, Miss., for amicus State of Miss.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Before BROWN, JOHNSON, and HIGGINBOTHAM,

Circuit Judges.

JOHNSON, Circuit Judge:

Plaintiffs, black registered voters in Orleans Parish,

Louisiana, raise constitutional challenges to the present

system of electing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

the First Supreme Court District. Plaintiffs allege that

the current at-large system of electing Justices from the

First District impermissibly dilutes the voting strength

of black voters in Orleans Parish in violation of Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1982

and the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. The dis

trict court dismissed the section 2 claim pursuant to Fed.

R.Civ.P. 12(b) (6) for failure to state a claim, finding that

section 2 does not apply to the election of state judges.

Concluding that section 2 does so apply, we reverse.

A p p . 7

The primary issue before this Court is whether sec

tion 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to state judicial

elections.

I. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The facts are undisputed. Currently, the seven Jus

tices on the Supreme Court of Louisiana are elected from

six geographical judicial districts. Five of the six dis

tricts elect one Justice each. However, the First District,

comprised of four parishes (Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaque

mines, and Jefferson Parishes), elects two Justices at-

large.

The population of the four parish First Supreme

Court District is approximately thirty-four percent black

and sixty-three percent white. The registered voter pop

ulation reveals a somewhat similar percentage breakdown,

with approximately thirty-two percent black and sixty-

eight percent white. Over half of the four parish First

Supreme Court District’s population and over half of the

district’s registered voters live in Orleans Parish. Im

portantly, Orleans Parish has a fifty-five percent black

population and a fifty-two percent black registered voter

population. Plaintiffs seek a division of the First District

into two single-member districts, each to elect one Justice.

Under the plaintiffs’ plan of division, one proposed dis

trict would be composed of Orleans Parish with a greater

black population and black registered voter population

than white. The other proposed district would be com

posed of Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Par

ishes ; this district would have a substantially greater white

population and white registered voter population than

black. It is particularly significant that no black person

A p p . 8

has ever been elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court,

either from the First Supreme Court District or from

any one of the other five judicial districts.

To support their voter dilution claim, plaintiffs cite,

among other factors, a history of purposeful official dis

crimination on the basis of race in Louisiana and the

existence of widespread racially polarized voting in elec

tions involving black and white candidates. Specifically,

plaintiffs allege in their complaint:

Because of the official history of racial discrimination

in Louisiana’s First Supreme Court District, the wide

spread prevalence of racially polarized voting in the

district, the continuing effects of past discrimination

on the plaintiffs, the small percentage of minorities

elected to public office in the area, the absence of

any blacks elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court

from the First District, and the lack of any justifiable

reason to continue the practice of electing two Jus

tices at-large from the New Orleans area only, plain

tiffs contend that the current election procedures for

selecting Supreme Court Justices from the New Or

leans area dilutes minority voting strength and there

fore violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended.

On May 1, 1987, the district court, 659 F.Supp. 183,

dismissed plaintiffs’ complaint for failure to state a claim

upon which relief may be granted. In its opinion accom

panying the dismissal order, the district court concluded

that section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not apply to

the election of state judges. To support this conclusion,

the district court relied primarily on the amended lan

guage in section 2 which states “ to elect representatives of

their choice.” The district court reasoned that since judges

are not “ representatives,” judicial elections are therefore

A p p . 9

not within the protective ambit of section 2. Focusing on

a perceived inherent difference between representatives

and judges, the district court stated, “ [j]udges, by their

very definition, do not represent voters but are ‘appointed

[or elected] to preside and administer the law.’ ” (cita

tion omitted). The district court further relied on what

was understood to be a lack of any reference to judicial

elections in the legislative history of section 2, and on pre

vious court decisions establishing that the “ one person,

one vote” principle does not apply to judicial elections.

As to plaintiffs’ fourteenth and fifteenth amendment chal

lenges, the district court determined that plaintiffs had

failed to plead an intent to discriminate with sufficient

specificity to support their constitutional claims. Plain

tiffs appeal the district court’s dismissal of both their

statutory and constitutional claims.

[1] In an opinion just released, the Sixth Circuit,

addressing a complaint that the present system of electing

municipal judges to the Hamilton County Municipal Court

in Ohio violates section 2, concluded that section 2 does

indeed apply to the judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d

275 (6th Cir.1988). Other than our district court, only

two district courts have ruled on the coverage of section

2 in this context. The Mallory district court, subsequently

reversed, concluded that section 2 does not extend to the

judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, 666 F.Supp. 1060 (S.D. Ohio

1987). The other district court, Martin v. Attain, 658 F.

Supp. 1183 (S.D.Miss. 1987), determined that section 2

does apply to the judicial branch. After consideration of

the language of the Act itself; the policies behind the en

actment of section 2; pertinent legislative history; previ

ous judicial interpretations of section 5, a companion sec

A p p . 1 0

tion to section 2 in the A ct; and the position of the United

States Attorney General on this issue; we conclude that

section 2 does apply to the election of state court judges.

We therefore reverse the judgment of the district court.

A. The Plain Language of the Act

The Voting Rights Act wras enacted by Congress in

1965 for a broad remedial purpose—“to rid the country

of racial discrimination in voting.” South Carolina v. Kat-

zenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 315, 86 S.Ct. 803, 812, 15 L.Ed.2d

769 (1966). Since the inception of the Act, the Supreme

Court has consistently interpreted the Act in a manner

which affords it “ the broadest possible scope” in com

batting racial discrimination. Allen v. State Board of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 565, 89 S.Ct. 817, 831, 22 L.Ed.2d

1 (1969). As a result ,the Act effectively regulates a wide

range of voting practices and procedures. See United-

States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners, 435 U.S.

110, 122-23, 98 S.Ct. 965, 974-75, 55 L.Ed.2d 148 (1978).

Referred to by the Supreme Court as a provision which

“broadly prohibits the use of voting rules to abridge exer

cise of the franchise on racial grounds,” Katzenbach, 383

U.S. at 316, 86 S.Ct. at 812, section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, prior to its amendment in 1982, provided as

follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny

or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in contravention

of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of

this title.

A p p . 1 1

Congress amended section 2 in 1982 in response to

the Supreme Court’s decision in Mobile v. Bolden, 446

U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980), wherein the

Court concluded that section 2 operated to prohibit only

intentional acts of discrimination by state officials. In

disagreement with the high court’s pronouncement, Con

gress amended section 2 with language providing that

proof of intent is not required to successfully prove a

section 2 violation. Instead, Congress adopted the “ re

sults” test, whereby plaintiffs may prevail under section

2 by demonstrating that, under the totality of the circum

stances, a challenged election law or procedure has the

effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on the

basis of race. However, while effecting significant change

through the 1982 amendments, Congress specifically re

tained the operative language of original section 2 defin

ing the section’s coverage—“ [n]o voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure

shall be imposed. . . . ” Section 2, as amended in 1982,

now provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political subdi

vision in a manner which results in a denial or abridge

ment of the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in contraven

tion of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f) (2)

of this title, as provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established

if, based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown

that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class

A p p . 1 2

of citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section

in that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the politi