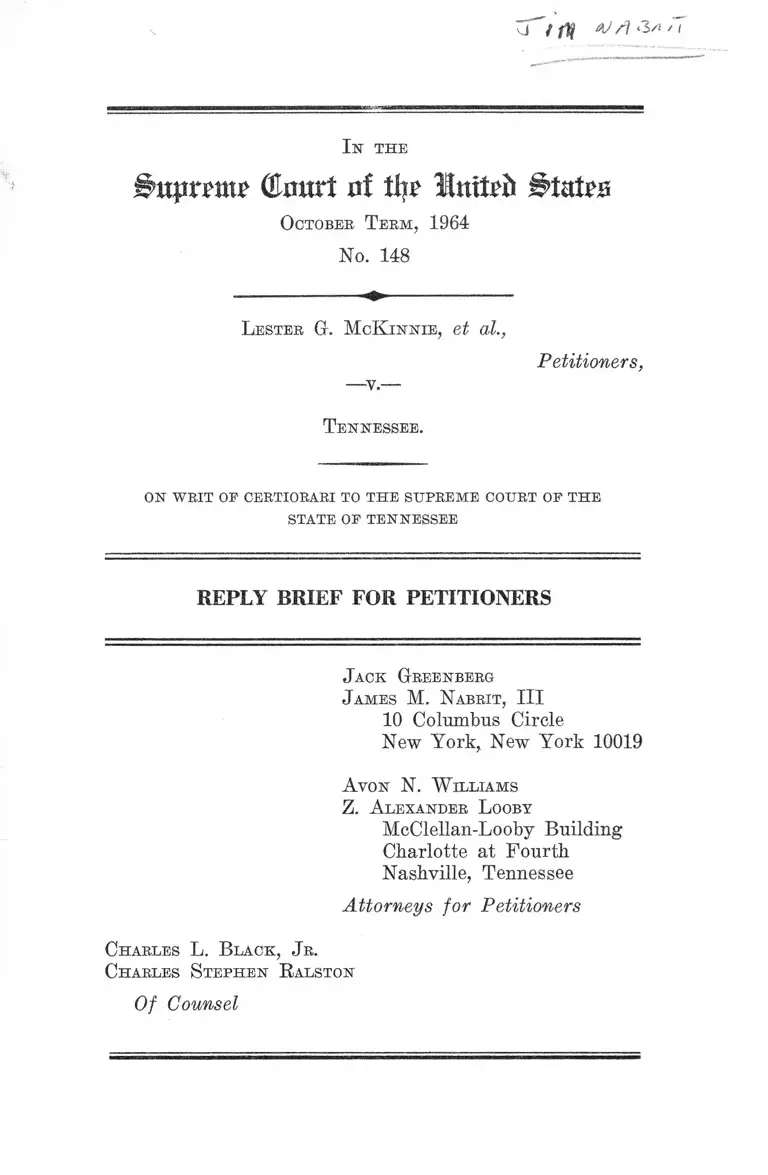

McKinnie v. Tennessee Reply Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinnie v. Tennessee Reply Brief for Petitioners, 1964. 629295a8-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95f8f308-e951-4bf3-9536-3ff2079706ab/mckinnie-v-tennessee-reply-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

?tt|irente (ta rt ii! % United States

October Term, 1964

No. 148

Lester G. McK innie, et al.,

—v.-

Petitioners,

Tennessee.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP THE

STATE OP TENNESSEE

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. Black, Jr.

Charles Stephen R alston

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Argument ...........—.... - ..... -..........................-..........-......... 1

I. The Civil Eights Act of 1964 Abates These

Prosecutions ........................................................... 1

PAGE

II. Petitioners’ Convictions Were an Enforcement

of Racial Discrimination by State Action in Vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment.................. 8

III. Petitioners Were Convicted on a Record Con

taining No Evidence of Guilt Contrary to

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 .............. 10

IV. Petitioners Were Substantially Prejudiced by

the Trial Judge’s Erroneous Instructions to the

Jury Concerning §62-710 of the Tennessee Code 11

V. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process Because

the Appellate Review of Their Convictions Did

Not Conform to the Rule of Cole v. Arkansas,

333 IT. S. 196 ........................................................ 14

VI. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process Because

the Jury Which Convicted Was Not Impartial

or Indifferent on a Central Matter Presented

to the Jury ........................................................... 17

T able of Cases

Arterburn v. State, 208 Tenn. 141, 344 S. W. 2d 362

(1961) ............................................................................ 13

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226 ................................... 16

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199 ............................... 4

Blow v. North Carolina, -——- U. S. L. Week ------ (Feb.

1, 1965) ........... ....... ................ -...... -............................. 1

Burgess v. State, ------ Tenn. ------ , 369 S. W. 2d 731

(1963) ........................... -............................................... 13

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ................................... 9

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 ........................14,15,16,17

Crawford v. State, 197 Tenn. 411, 273 S. W. 2d 689

(1954) .......... .............................................................. 13

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353 ................................... 15

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 .................. 4

Fox v. North Carolina, 378 U. S. 587 ......................... 8,10

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 .............. .......—.7,14,16

Hamm v. City of Bock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 .............. 1, 2, 4, 6,

17,18

Hormel v. Helvering, 312 U. S. 551 ................................ 14,15

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U. S. 717 ............................. 18,19

King v. State, 83 Tenn. 51 (1885) .............................. 13

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 267 ......................... 8,16

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962) .......... 3

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) .......... 3

Palmer v. Hoffman, 318 IT. S. 109 ................................. 12

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331 ................. 4

ii

PAGE

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ..............8,10

Potter v. State, 85 Tenn. 88, 1 S. W. 614 (1886) ....... 13

Powers v. State, 117 Tenn. 363, 97 S. W. 815 (1906) .. 13

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 ........................8,10,16

Russell v. United States, 369 U. S. 749 ........................ 16

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339 ....14,16

State v. Lasater, 68 Tenn. 584 (1877) ..................3, 9,10,11

Stirone v. United States, 361 U. S. 212 ...................... 17

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................12,14

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ................................. 14

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 .......................... 10

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 .................................9,10

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 .................................13,14

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 .................................7,11

F ederal, Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 335 ......................... 4

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 241 ....1, 2, 4, 6, 8

State Statutes

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-1101(7) ........................................ 7

Tenn. Code Ann. §53-2120 .......................... ................... 9

Tenn. Code Ann. §62-710 ............................. 3, 7, 8,11,12,17

Tenn. Code Ann. §62-711 ............................................ 3, 9,10

Tenn. Code Ann. §62-715 ................................................ 9

Chapter 130, Acts of Tennessee, 39th General As

sembly, 1875

I l l

PAGE

4

XV

Regulation No. R-18(L) of the Division of Hotel and

Restaurant Inspection of the State Department of

Conservation ................................................................. 9

Other A uthority

110 Cong. Rec. 9463, daily ed., May 1, 1964 ................ 6

PAGE

1st the

0uprm£ Court 0! tip Httitrft States

October Term, 1964

No. 148

L e s t e r GL McK innie, et al.,

Petitioners,

— v.—

T ennessee.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF TENNESSEE

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

On December 14, 1964, after petitioners’ brief was filed,

this Court decided Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S.

306. The purpose of this reply brief is to discuss the ap

plicability of that decision, and to reply to arguments made

by the Respondent.

I.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Abates These Prosecutions.

After certiorari was granted in this case,1 and after peti

tioners’ brief was filed, this Court held in three cases that

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II, requires that convic

tions in pending prosecutions similar to this one be vacated

and the indictments dismissed. Hamm v. City of Rock Hill

(and Lupper v. Arkansas), 379 U. S. 306; Bloiv v. North

Carolina,------U. S. L. W eek------- (Feb. 1, 1965). These

1 379 U. S. 811, October 12,1964.

2

decisions rested on the ancient common law doctrine of

abatement, and on the language and purposes of the Act,

including particularly §203(c).2 We respectfully submit

that notwithstanding the fact that these decisions were

not unanimous (see dissenting opinions in Hamm, 379 U. S.

at 318, et seq.), the holding of the Court with respect to

the meaning and effect of this important act of Congress

should now be accepted as stare decisis. Tennessee has not

challenged the basic ruling of Hamm, supra, but has at

tempted to show that this case is different (State’s Brief,

pp. 5-8).

We contend that the State’s attempted distinctions fail,

and that a holding distinguishing Hamm on the grounds

suggested on this record would substantially undermine the

effectiveness of the Civil Rights Act as applied to criminal

convictions for acts done before and since passage of the

Act.

First, it should be noted that Tennessee has not argued

that the B & W Cafeteria is not a place of public accommo

dation covered by the Act. It assumes the contrary (State’s

Brief, p. 5), as South Carolina and Arkansas did in the

Hamm case (379 U. S. at 309-310).3

2 §203(c) provides:

“No person shall . . . (c) punish or attempt to punish any

person for exercising or attempting to exercise any right or

privilege secured by Section 201 or 202.”

See also §§201 (b) (2) and (c) (2) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

3 The correctness of this assumption is clear, since it is uncontra

dicted that the cafeteria was open to the general public (R. 94),

and hence “offers to serve interstate travelers.” Section 201(c) (8)', '

Civil Rights Act of 1964. The indictment alleged that the B & W

Cafeteria Inc., was “ a restaurant and cafeteria, elaborately fur

nished and equipped, . . . in the heart of the business, commercial

and uptown district of Nashville, Tennessee, . . . with a large

seating capacity for customers . . . [and a] reputation as serving

3

Second, it is undisputed that petitioners sought and were

denied enjoyment of the goods and services of the cafeteria

solely because of their race; the cafe manager (among

others) flatly testified to this (R. 94-95). The State’s pres

ent assertions that this is not a case involving racial dis

crimination are so patently contrary to the evidence, the

indictment, the State’s own theory at trial, and the pro

ceedings at every stage of the trial as to be unworthy of

serious consideration.4 Time and again states have made

such arguments to this and other courts, but only rarely

has it been attempted on a record so permeated with the

race question from first page to last on the State’s own

theory of the trial.5 The claim is all the more bizarre

in this case where the law used to convict petitioners was

admitted candidly by a contemporary Tennessee Supreme

Court to have been “an extraordinary statute” “passed to

avoid the supposed effects of an act of Congress on the same

subject, known as the civil rights bill” of 1875. State v.

Lasater, 68 Tenn. 584, 585 (1877).6

fine foods and which said cafeteria daily served hundreds of white

patrons, customers and clientele (R. 2). The manager testified

that “ adjacent and nearby” businesses were a jewelry store, a

furrier, the Eastern Airlines office, the Cross Keys Restaurant

and the Hermitage Hotel (R. 89) ; and that the capacity is 450

customers (R. 88).

4 See, for example, R. 1-5.

5 In a celebrated case where the pretense of racial neutrality

was maintained from the start, Judge Wisdom of the Fifth Circuit

wrote that it “was tried below and argued here in the eerie at

mosphere of never-never land.” Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696,

701 (5th Cir. 1962) ; see also, Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 343, 345

(5th Cir. 1962).

6 The indictment charged petitioners, among other things, with

a conspiracy to violate Term. Code Section 62-711. It also men

tioned Section 62-710. Petitioners argue (see Part IV, infra) that

the jury was erroneously instructed that they were charged with

violating this law as well. Sections 62-710 and 62-711, respectively,

were originally sections 1 and 2 of the Act which may be found

4

Thirdly, in conjunction with the new posture of racial

neutrality, the State argues that the Hamm case is inap

plicable because, it is asserted, petitioners did not behave

in a “ peaceful manner” and their conduct is unlawful with

out regard to the race issue (State’s Brief, p. 5). There

are multiple answers to this contention. They may be sum

marized by stating that the record and a reasonable con

struction of the Civil Bights Act of 1964 do not support the

assertion, and that in any event, considering the accusation,

jury instructions and evidence, the jury’s general verdict

does not necessarily, or even probably, indicate that the

jury believed that petitioners were not “peaceful.”

We submit that the record demonstrates that the conduct

of petitioners was within the statement in Hamm v. City

of Hock Hill, 379 U. S. 306, 311, that “nonforcible attempts

to gain admittance to or remain in establishments covered

by the Act, are immunized from prosecution.” Needless to

say, this Court is not bound by the State Supreme Court’s

characterizations of the facts or prevented from making its

own “ independent examination of the whole record” in de

ciding the federal claim. Edwards v. South Carolina, 372

U. S. 229, 235; Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199; Penne-

kamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331, 336.

Such an examination shows clearly the following. Peti

tioners sought entry to the B & W Cafeteria on October 21,

1962. They attempted to go into the cafeteria, but were

prevented from doing so because the doorman blocked en

in Acts of Term., 39th Gen. Assembly, 1875, Ch. 130, pp. 216-217

(passed March 23, 1875; approved March 24, 1875). There have

been only minor changes since the original enactment: (a) the

parenthetical phrase— “ (except railways, street, interurban and

commercial)”— was added to section 1; (b) minor stylistic changes

in both sections.

The Act was an immediate response to the federal Civil Rights

Act of 1875 which was approved March 1, 1875 (18 Stat. 335).

5

trance through the inner doors of the vestibule (R. 271, 100-

101, 228-229). Clearly they would have gone in and obtained

service if they had been allowed to do so (R. 94, 100-101,

289-290).7 The record is completely devoid of any evidence

that petitioners had planned, or wished, to block the en

trance. Therefore, this case is certainly not one of a de

liberate obstruction of an entry way in order to disrupt

business. Any obstruction or inconvenience to white cus

tomers was incidental to their unsuccessful demand for

service.

Indeed, all the evidence supports the conclusion that the

real cause of the obstruction of the doorway was the door

man’s refusal to allow petitioners to move out of the vesti

bule and into the cafeteria (R. 100-101, 165, 228-229). Peti

tioners allowed numerous customers to pass by them,

conduct not compatible with a deliberate scheme to in

terfere with the B & W ’s business (R. 91-93, 109, 164).

Even the evidence that petitioners were “pushing and shov

ing” (R. 168, 169, 214, 278-280) is explained largely by

testimony that this was caused in part by white patrons

coming through the crowded vestibule (R. 175-177, 279-280).

There was nothing more than the casual jostling normally

encountered in crowded public places. Petitioners could

have forced entry if they had wished, considering the age

and size of the doorman (see Petitioners’ Brief, p. 6), but

as the doorman admitted, they did not try “ to fight their

way in” (R. 228). It would be hard to think of an example

of a non-forcible attempt to gain entry, if this is not one.

Petitioners standing at the door represented the only way

open to them at the time to nonviolently request service.

7 Even the testimony of witnesses that one of petitioners said,

“When we get there, just keep pushing. Do not stop. Just keep on

pushing,” indicates that they wished to go into the cafeteria, and

did not want to prevent others from doing so (B. 210-211, 219-222).

6

If admitted they would have purchased food. The cafeteria

employees’ conduct prevented them from ordering food.

Examining the occurrences as if they had taken place

after enactment of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 illuminates

the problem. The restaurant employees would obviously

violate their duties under the Act by blocking petitioners’

entry. By standing in the vestibule and thus continuing to

seek entry, petitioners, asserting rights under the Act,

might by their presence make it more inconvenient for

white customers to enter. But surely the policy of the

Civil Rights Act would prevail over any incidental incon

venience to customers coincident with and directly flowing

from wrongful action of the restaurateur in defiance of the

Act. We submit that this is exactly the type of situation

Vice President (then Senator) Humphrey envisioned when

he explained that the bill meant that “a defendant in a

criminal trespass, breach of the peace, or other similar case

can assert the rights created by 201 and 202 and that State

courts must entertain defenses grounded upon these pro

visions . . . ” (Cong. Rec., May 1, 1964, p. 9463; and see

Hamm, supra, 379 U. S. at 311). A contrary holding would

invite nullification of the Act by hostile prosecutors and

fact finders. And, of course, this does not mean that the

Act affords a shield for really violent conduct, any more

than it was ever suggested by courts which supported the

view that proprietors could exclude for racial reasons that

the right of self-help excused such violence by restaura

teurs.

However, even if the foregoing analysis is not accepted,

that is by no means the end of the matter because in light

of the manner in which the case was presented to the jury,

the general verdict of guilty does not indicate that the jury

believed that petitioners were not acting in a peaceful, non

violent manner. (Matters pertinent to this are argued ex

7

tensively below in connection with the arguments about the

trial judge’s instruction to the jury and the nature of the

indictment.) Indeed, the jury could have followed its in

structions and nevertheless convicted if it merely believed

that petitioners tacitly agreed to challenge the proprietor’s

right to exclude Negroes,8 or that they tacitly agreed to

seek service nonviolently but knowing that they ran the

risk of being attacked by white bystanders or patrons.9

Surely the case was never presented to the jury with in

structions to determine merely whether petitioners used

violent means or deliberately blocked the door to assert

their own lawful right to enter against a proprietor who

was lawlessly excluding them. The case was presented to

8 The judge read Section 62-710, conferring a right to exclude

Negroes (R. 298) ; read the indictment which embraced that theory

(R. 292-296) ; told incorrectly that the petitioners were charged

with violating Section 62-710 on three separate occasions (R. 299,

302, 305) ; and also told (in defining acts “ injurious” to restaurant

trade or business as used in the conspiracy statute (§39-1101(7))

that injurious “ generally means in law, invasion or violation of

legally protected interest or property right of another” (R. 300).

(Note that the court refused to give requested instructions that

the restaurant had no right to exclude racially (R. 310). What is

more it also deleted the key language of another requested instruc

tion that might have made it clear that petitioners’ mere agreement

to seek entry even though the cafeteria had a policy of refusing

to serve Negroes was not unlawful. Compare requested instructions

at E. 307 (deleted language in brackets) with actual instruction at

R. 311.)

9 The indictment, which was read with approval to the jury

during the instructions by the Court contained an allegation that

defendants did certain acts “well knowing that their presence as

‘sit-ins’ was likely to promote disorders, breaches of the peace, fights

or riots by patrons, customers and clientele of such segregated

cafeteria” (R. 295, emphasis supplied). The indictment also as

serted that previous sit-ins had “resulted in fights, breaches of the

peace, disorders, brawls and riots” (R. 295). This invited convic

tion on a theory, obviously unconstitutional under Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, and Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284,

292, that petitioners’ acts were unlawful because they knew that

others might attack them.

8

the jury on precisely the opposite basis, by a jury charge

which included a reading of the indictment and Code Sec

tion 62-710 with approval of the legal theories therein (E,

292-296, 298, 300, 302, 305). To view the matter another

way, and make it more than obvious, no one could reason

ably contend that the indictment or charge to the jury were

proper if they had taken place after passage of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964. Any conviction after enactment of

Title II that was based on such an accusation or such a

jury instruction would be summarily reversed. The pre

act conviction based on such a case falls by the same token

because based on a general verdict arrived at by a jury

erroneously instructed as to the law.

II.

Petitioners’ Convictions Were an Enforcement of

Racial Discrimination by State Action in Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

The State’s brief makes no attempts to give a direct an

swer to petitioners’ arguments based on the Fourteenth

Amendment. However, a few additional remarks are ap

propriate.

Tennessee has by its laws and administrative regulations

directly encouraged and required segregation in violation

of the principles set forth in Lombard v. Louisiana, 373

U. S. 267; Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244; Robinson

v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153; and Fox v. North Carolina, 378

U. S. 587.

First, we have mentioned above that the laws used to

convict petitioners were passed by Tennessee in 1875 in an

attempt to evade the Civil Eights Act of 1875 dealing with

s etsftnf) r>

9

public accommodations.10 The judicial acknowledgment of

this is corroborated by the fact that the Tennessee law

paraphrased in exactly the same order the categories of

accommodations covered by the federal act passed that same

month.11 This was certainly an admitted state encourage

ment of racial discrimination in restaurants, which are ex

pressly mentioned in the act’s second section (now §62-711).

But beyond this the State has taken administrative action

to require segregation, as was brought to this Court’s at

tention in Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350, 351. The

Turner case involved Regulation No. R-18(L) of the Divi

sion of Hotel and Restaurant Inspection of the State De

partment of Conservation providing:

Restaurants catering to both white and negro patrons

should be arranged so that each race is properly segre

gated. Segregation will be considered proper where

each race shall have separate entrances and separate

facilities of every kind necessary to prevent patrons

of the different races coming in contact with the other

in entering, being served, or at any other time until

they leave the premises.12

Violation of this regulation was a misdemeanor punish

able by fine pursuant to Tennessee Code Section 53-2120.

; 10 See Note 6 above and accompanying text. State v. Lasater,

68 Tenn. 584, 586 (1877).

11 This is also a repudiation of the assumption made in The Civil

Rights Cases, that common law protected access to places of public

accommodation, but although a Tennessee case was involved the

law apparently passed unnoticed by the court (109 U. S. 3, 24).

After the Civil Rights Cases, supra, Tennessee grew bolder and

explicitly declared the right to segregate in certain places of public

accommodation. See Tenn. Code Ann. Section 62-715 (derived

from Acts 1885, ch. 68, §4).

12 The quotation of the regulation is taken from the printed

record in this Court in Turner v. Memphis, 369 TJ. S. 350, Oct.

Term, 1961, No. 84, Record pp. 7, 19-20.

10

To be sure, the above-mentioned statute and regulation

were held unconstitutional in Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S.

350, 353 (March 26, 1962), some 7 months before petitioners

in this case were arrested. However, petitioners submit

that the provisions represent such a clear and unequivocal

state endorsement of the desirability of segregation as to

be at least the legal equivalents of the invalid state encour

agement of segregation in Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S.

153, and Fox v. North Carolina, 378 U. S. 587. Indeed,

even the segregation ordinance involved in Peterson v.

Greenville was clearly a nullity at the time the arrests in

that case took place under the same precedents cited for

invalidating the Tennessee provisions in Turner (369 U. S.

at 353).

III.

Petitioners Were Convicted on a Record Containing No

Evidence of Guilt Contrary to Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U. S. 199.

It is submitted that the State has not sufficiently rebutted

petitioners’ argument that there was no evidence sufficient

to find them guilty of a conspiracy to violate the statutes

mentioned in the indictment. The argument that there is

no evidence supporting the charge that they conspired to

obstruct the restaurant unlawfully has been detailed in the

plaintiffs original brief and in part I of this brief above.

However, it should also be emphasized that there was no

evidence of a conspiracy to commit “ turbulent or riotous

conduct.” 13 The Court below defined “ riotous” by refer

13 It should be noted that the conspiracy conviction carried with

it a jail term as well as a fine, penalties much more severe than

those for a simple violation of Section 62-711. But State v. Lasater,

68 Tenn. 584, 586 (1877) the Court said that the penalties in

§62-711 itself were “severe, more so than in other kindred offenses”

but overturned a trial court decision that the $100 fine and $500

forfeiture under the act were a cruel and unusual punishment.

11

ence to the dictionary as “having the nature of a riot or

disturbance of the peace” (R. 319).14 In the same para

graph the court relates this to the problem of proving a

conspiracy. There was plainly no evidence in the case that

any actual riot occurred or that there was any breach of

the peace. The Court’s conclusion that petitioners’ conduct

met its definition might have adopted the unconstitutional

theory in the indictment (R. 4), that petitioners’ actions

might have provoked an attack by others.15 Cf. Wright v.

Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 292-93. Otherwise there is no evi

dence that the petitioners conspired to cause a riot. Peti

tioners raised both the “ no evidence” and a vagueness claim

(R. 17-18, 21, 22, 25) expressly relying on the Fourteenth

Amendment.

IV.

Petitioners Were Substantially Prejudiced by the Trial

Judge’s Erroneous Instructions to the Jury Concerning

§62-710 of the Tennessee Code.

The State contends that the Trial Judge’s error in the

charge to the jury was “ in the nature of a typographical

or clerical error as obvious to the jury as to counsel for

the petitioners” and hence was harmless (State’s Brief,

pp. 13-14).

The suggestion that the trial judge’s error was a mere

inadvertence comparable to a slip of the tongue is readily

subject to refutation. To start with the judge did not

14 In State v. Lasater, supra, the only prior construction of the

law that has come to our attention, the law was held applicable

to an allegation that a defendant engaged in “ quarreling, com

mitting assaults and batteries, breaches of the peace, loud noises,

and trespass upon a hotel.”

15 See Note 8 supra.

12

merely tell the jury once that petitioners were charged

with conspiring to violate §62-710. He told them this three

times. In addition, he not only read the statute to the jury,

he also read the grand jury presentment which relied on

the statute and indeed made a variety of references to

restaurateurs’ purported right to exclude Negroes. The

harmful potential of this coupled with the instruction that

a conspiracy under the law included injury to a “ legally

protected interest or property right” (R. 300) is patent.

The fact that the trial judge denied contrary instructions

also shows that the error was not an inadvertence.

We submit that the instructions under §62-710 could

have led a jury of laymen to believe that they could find

petitioners guilty solely because they sought to induce the

cafeteria to serve them by nonviolently challenging its

segregation policy established pursuant to §62-710. The

Court below said “ the only purpose in referring to this

statute was to indicate that this restaurant was being oper

ated for white people only by authority of this section”

(R. 321). That is exactly what was wrong with reading

the statute to the jury. It asserted that the proprietor’s

racial policy was valid and relevant—a theory, incidentally

at odds with the pretense that race was not involved in

the case.

The emphasis on §62-710 in the indictment and jury

charge is at the heart of the invitation to the jury to decide

the case on a variety of unconstitutional grounds such as

those mentioned in the text accompanying notes 7 and 8

above. This requires reversal of the convictions under

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359.

The State also argues that petitioners failed to object

when the instruction was given, and cites the case of Palmer

v. Hoffman, 318 U. S. 109, 119-120. However, the decision

13

there involved and turned on a rule of federal procedural

law, and is therefore inapplicable. Neither the Supreme

Court of Tennessee (R. 321) nor the State in its brief (pp.

13-14) pointed to any Tennessee authority that would

establish that petitioners failed to raise the issue properly

by requesting a contrary instruction,16 followed by citing

the erroneous instruction in its motion for a new trial (18-

19).17 Moreover, the Tennessee Supreme Court only men

tioned that no questions were raised about the propriety

of reading the section, and then proceeded to decide on the

merits that the error was harmless. Quite possibly the Court

thought that this passing mention supported its harmless

error holding and intended no procedural implication at all.

Since the state court, if it considered the matter procedur-

ally, exercised an apparent discretion to decide the issue,

there is no reason for this Court to decide that it is barred

16 See R. 310. Defendants’ Special Request No. 4 sought to have

the jury instructed that Section 62-710 could not constitutionally

form the basis of enforcing a policy of racial segregation or exclu

sion through a criminal action.

Apparently, under Tennessee law the requesting of an instruc

tion in opposition to the one given is a sufficient objection. Cf.,

Arterburn v. State, 208 Tenn. 141, 344 S. W. 2d 362 (1961) ;

Crawford v. State, 197 Tenn. 411, 273 S. W. 2d 689 (1954) ;

Powers v. State, 117 Tenn. 363, 97 S. W. 815 (1906).

Moreover, the appellate courts do have discretion to rule on the

validity of an instruction even where no contrary request has

been made. See, Potter v. State, 85 Tenn. 88, 1 S. W. 614 (1886);

King v, State, 83 Tenn. 51 (1885). This is particularly the case

where the judge’s error has been an affirmative one, as was the

case here. Thus, in Burgess v. State,------ Tenn.--------, 369 S. W. 2d

731 (1963) the trial judge had charged the jury by reading them

the language of a statute that had been passed after the defendant

had committed the offense. The Supreme Court of Tennessee

reversed, even though no special request for a different instruction,

or apparently any other objection, had been made. Thus, under

the rule of Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, this court is not

barred from deciding the question.

17 The record does not indicate what, if any, other opportunities

were given petitioners to object to the erroneous instruction.

14

from also determining the question.18 Williams v. Georgia,

349 U. S. 375; Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376

U. S. 339.

V.

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process Because the

Appellate Review o f Their Convictions Did Not Conform

to the Rule of Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196.

Petitioners have argued that the appellate review af

forded below did not conform to due process because their

convictions were not appraised “ on consideration of the

case as it was tried and as the issues were determined in

the trial court.” Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196, 202. The

State has replied that the Tennessee Supreme Court found

an independent ground to support the judgment even as

suming, as petitioners contended, that the racial policy of

the cafeteria was illegal, and that in so holding the state

court merely followed the usual appellate principle of avoid

ing the unnecessary decision of constitutional questions.

The State relies on Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157,

and Hormel v. Helvering, 312 U. S. 551.

We submit that neither the reasoning nor the authorities19

cited by the State refute petitioners’ argument that the ap

18 See Note 16 supra. In addition, Strom,berg v. California, 283

U. S. 359, and Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, indicate that

even if there had been a failure to properly object, this Would not

bar the challenging of an erroneous instruction where the error

was sufficiently prejudicial.

19 Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, was a case where the Court

reversed convictions and freed convicts, finding it unnecessary to

reach all their claims. This is a quite different matter from sending

men to jail without deciding their properly presented constitu

tional claims by seizing on a theory directly contrary to that upon

which the jury was instructed to decide the ease.

Hormel v. Helvering, 312 U. S. 552, was a civil tax case where

the Court recognized the general rule that appellate courts should

not consider issues never raised below in order that parties may

15

pellate court unfairly sustained their convictions on a

ground not litigated.

The Tennessee Supreme Court said that: “ Stripped of

any question of race and discrimination, the act complained

of is still unlawful” (E. 324). Aside from the fact that one

must disregard the facts to strip the case of race issues,

the problem with this is that the jury never considered the

facts “ stripped of any question of race and discrimination,”

and the defense never had notice of or opportunity to defend

against any such charge. The issues of whether petitioners

used illegal means to enter a place they had a right to

enter was never put before the jury, and was not fairly

presented by the indictment. It "was decided by the Supreme

Court of Tennessee in the first instance. Thus petitioners

were convicted “ upon a charge not made” a “ sheer denial of

due process” DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 362.

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196, 201, emphasizes that

notice of the specific charge and a right to be heard at

trial of the issues raised by the charge is essential to a fair

trial. If petitioners had notice of this quite different charge,

their cross-examination and argument might have been dif

ferent. Indeed, faced with such a charge defense counsel

might have evaluated the risks differently and found it

prudent to call on the defendants to testify in their own

defense. This determination alone can vitally affect the

outcome of a trial.20 As the charge was actually framed,

have an opportunity to offer evidence on the relevant issues. But

recognizing that the rule was not inflexible, the Court found that

in the particular case an injustice would result if the case was not

decided on the basis of the correct rule of law as embodied in

statute not mentioned before the Board of Tax Appeals. We

submit that in this case the failure to apply the general rule

stated in Hormel, supra, has resulted in an injustice to petitioners

whose liberty is at stake.

20 A defendant’s failure to testify obviously may have an impact

on the jury even if it is admonished not to hold his failure against

him.

16

and the case actually tried the tactical considerations for

defense counsel were quite different because the state’s case

at trial flatly rested on the premise that state judicial en

forcement of racial segregation did not violate the Four

teenth Amendment. Defense counsel might very reasonably

stake the defense on the belief that this proposition was

wrong (Of. Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267; Robinson

v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153; and the concurring opinions in

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226), but they might well have

taken an entirely different view of defense tactics and put

on defensive proof if faced with a charge that the defen

dants used illegal means of self-help in support of a law

ful right to enter the premises.

In Russell v. United States, 369 U. S. 749, 766 the Court

made it clear that the reasoning of Cole v. Arkansas, supra,

was not limited to the case where an appellate court ex

plicitly switched statutes on a defendant.21 In reversing be

cause of a vague indictment the court said (369 U. S. at

766):

“It enables his conviction to rest on one point and the

affirmance on another. It gives the prosecution free

hand on appeal to fill in the gaps of proof by surmise or

conjecture. The Court has had occasion before now to

condemn just such a practice in a quite different factual

setting. Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196, 201, 202.”

In Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, this Court rejected

a request that it do something similiar to what was done by

the Tennessee Court. Louisiana argued that although de

fendants were convicted of disorderly conduct, the real issue

was whether the record proved the elements of a criminal

trespass. The Court rejected the argument on the authority

of Cole, supra. Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 164.

21 This occurred in Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339.

17

Here the Tennessee Supreme Court convicted the defen

dants on a charge that the trial jury never considered

and which the grand jury never made. Cole v. Arkansas,

supra; Stirone v. United States, 361 U. S. 212.

The prosecution thus attempts, we think unfairly, to get

the benefit of the emotionally charged segregation issue be

fore a favorably disposed jury (see Argument VI, infra),

while attempting to cleanse the ease of the race issue for

review in this Court, in the face of adverse precedent

(Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 TJ. S. 306).

VI.

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process Because the

Jury Which Convicted Was Not Impartial or Indifferent

on a Central Matter Presented to the Jury.

Petitioners have argued from the very beginning that

they were denied due process because the jury which tried

them was prejudiced against them as evidenced by the

jurors’ admitted life-long practice, custom and philosophy

of racial segregation.22 The relationship of this point to

the objection to the indictment and its references to the

cafeteria’s segregation policy under Section 62-710 was

pointed out to the trial court during the jury selection

process (B. 59-60, 63).

22 Only a portion of the lengthy voir dire proceedings to select

the jury have been printed in the record in this Court (R. 29-87),

however, the entire original record in typewritten form is on file

in this Court. In addition to the general objection, the motion

for new trial (R. 24-25) raised particular objections to jurors

Win. T. Moon, Wendell H. Cooper and Herbert Amic, reiterating

objections made during the voir dire itself. Moon and Cooper

were seated after all of petitioners’ peremptory challenges were

exhausted; others were seated over petitioners’ protests that chal

lenges for cause were improperly denied though they declined to

use their limited number of peremptory challenges.

18

The State’s brief in this Court argues first, that there was

no showing that the jurors were prejudiced about an issue

that was involved in the case, and second, that the jurors

stated that their opinions were not so fixed that they could

not try the case impartially.

The State’s first point is patently erroneous. The case

was presented to the jury by the indictment and the judge’s

instructions as a case centrally concerned with the question

whether petitioners conspired to deprive the cafeteria of

its explicitly assumed right to exclude Negroes. The case

was submitted to the jury on an instruction exactly con

trary to the arguendo assumptions made by the Tennessee

Supreme Court, and the ruling of Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379

U. S. 306, i.e., that petitioners had a right to service and

the proprietor no right to exclude them. Note that the

jurors’ prejudice was not a mere “mistake of law” as urged

by the state; their prejudice was about what the law should

be and their view was that restaurants should be allowed

to discriminate racially. The prejudice was expressed in

these terms by juror Amic, and was plainly implicit in the

testimony of the others who believed in and practiced seg

regation in every area of their daily lives.

But this Court has held that “ the right to jury trial guar

antees to the criminally accused a fair trial by a panel of

impartial, ‘indifferent’ jurors.” Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U. S.

717, 722. The fair jury is a basic requirement of due proc

ess. In Irvin the Court quoted with approval Lord Coke

who said “a juror must be as ‘indifferent as he stands un-

sworne’ Co Litt 155b” (366 U. S. at 722).

In answer to the state’s second point, Irvin v. Dowd,

supra, makes it plain that while it is sufficient that a juror

can lay aside his impression or opinion and render a ver

dict on the evidence, this rule does not foreclose inquiry

even if every juror says that notwithstanding his opinion

19

he can render an impartial verdict, and holds that “ impar

tiality is not a technical conception” (366 U. S. at 723-724).

In Irvin the Court held the trial unfair because a va

riety of evidence such as newspaper comment and re

porting of the crime demonstrated a “pattern of deep and

bitter prejudice against” the defendant (Id. at 727). The

evidence of the pattern of segregationist belief in this case

came from the jurors and veniremen themselves, as one

after another the white jurors expressed this view and

every Negro juror was either excused for cause or per

emptorily challenged by the state.

Juror Amic, after telling the Court that he could be im

partial (E. 61-62) practically returned to his earlier ex

pression (E. 62):

Q. Wait just a minute—please, sir. That if evidence

was shown in this case—that if the indictment charges

that the defendants went there, knowing of this rule

and the defendants, being Negroes, sought service, that

it would prejudice you against them?

A. Well, it would have to be shown to me that it

was—that they did violate some regulation like that.

* # # * #

Q. But, if they had a rule that they excluded Negroes,

and these defendants went there and violated that rule,

it would prejudice you against these defendants,

wouldn’t it?

A. If—if it was a proven fact that that was their

rule, and that they were there against the cafeteria’s

rule, why I think they have a right to enfore (sic)

that rule.

Q. And you would start out with that prejudice

against the defendants, wouldn’t you?

A. Not necessarily, not until it is proven exactly

they did violate the rule and violate some law.

20

In particular it was argued that juror Herbert Amie was

erroneously held competent, despite petitioners’ objections,

after testifying that he believed a business open to the

public should be allowed to exclude Negroes; that in such

a case he would start out with a prejudiced attitude toward

the petitioners; and that the cafeteria would be right in

its position (R. 56-57).

Petitioners were denied a jury which was “ impartial”

and “ indifferent” on the principal issue presented to it for

decision by the instructions and indictment. It is reason

ably inferable that the prosecutor prepared the indictment

emphasizing race in order to exploit the segregationist

attitudes of local jurors. The state may not now avoid

the consequences of that decision.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. B lack, Jr.

Charles Stephen R alston

Of Counsel

38